Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 11

November 26, 2013

The Early Career of Edward Seymour

Although Henry VIII’s marriage to Jane Seymour would transform the fortunes of her oldest brother, Edward Seymour was a rising man before his sister caught the eye of the king.

Edward was born around 1500 to John and Margery Seymour, whose chief residence was Wolf Hall in Wiltshire. He was his parents’ second son; his older brother, John, died young.

It has been claimed that Edward was educated at Oxford and Cambridge, but his stays there are not documented, although David Loades notes that it was not unusual for young gentlemen to spend only a brief period at a university in order to give themselves a polish. Edward was certainly presentable enough to be chosen in 1514 as a “page of honor” to accompany Henry VIII’s younger sister Mary to France for marriage to Louis XII. Among Mary’s other attendants was a young “Mademoiselle Boleyn.” Three years later, on July 14, 1517, Edward and his father were made the joint constables of Bristol Castle.

By 1518, Edward had married Katherine Fillol and had his first son, John. A second son, Edward, followed in due course, but the marriage would prove to be an unhappy one, possibly due to infidelity on Katherine’s part, as Edward would later come to doubt the paternity of his eldest son. Much later, it was alleged that Katherine had had an affair with her own father-in-law, but there is no evidence that this story was current during the sixteenth century. Certainly nothing indicates that Edward or his father was shunned at court or that father and son were estranged, as is claimed by some popular historians. Edward did, however, repudiate his wife, whose father’s 1527 will gave her an annuity of forty pounds “as long as she shall live virtuously and abide in some house of religion of women.”

In 1523, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, led an expedition into France. Among the young men knighted by Suffolk at Roye on November 1, 1523, was Edward. Three days later, another up-and-coming young man, John Dudley, was knighted.

Before Christmas of 1524, some of the esquires of the king’s household, including Edward Seymour and John Dudley, sent Windsor Herald into the queen’s chamber to propose a feat of arms. A mock fortress, known as the Castle of Loyalty, was duly built at Greenwich, and the king himself took part in assaulting it. The chronicler Hall commented, “I think that there was never battle of pleasure, better fought than this one.”

While the assaults upon the Castle of Loyalty were taking place in January and February 1525, Edward Seymour was made a justice of the peace for Wiltshire on January 12. That same year, the king appointed him master of the horse for Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, the king’s illegitimate son. Two years later, Edward accompanied Cardinal Wolsey on an embassy to France. In September 1530, he became an esquire to the body to Henry VIII, for which he received an annuity of 50 marks.

Edward’s New Year’s gift to the king in January 1532 was “a sword, the hilts gilt with ‘kalenders’ upon it.” That same year, Henry took Anne Boleyn, soon to become his second queen, to Boulogne. Ironically, in light of later events, Edward and his father were among the entourage accompanying the happy couple abroad. Father and son each had eight attendants. When Anne was crowned queen in June 1533, Edward served as the carver for the Archbishop of Canterbury.

It was also in 1533 that Edward became involved in a messy legal dispute with Arthur, Lord Lisle, the illegitimate son of Edward IV. Lisle was the stepfather of Sir John Dudley, who held the reversion to certain land occupied by Lisle, and the dispute stemmed from Dudley’s sale of his reversionary rights to Edward Seymour. The complex dispute, detailed painstakingly by M. L. Bush, shows an unscrupulous, acquisitive side of Seymour (an aspect, admittedly, not lacking in other courtiers) and also shows Seymour’s growing influence with the king: in 1534, it was believed that the king would support Seymour over his natural uncle. The dispute dragged on through 1537, and ended with Seymour in possession of the land in question.

Sometime before March 9, 1535, when Henry granted Edward and his wife land in Hertfordshire, Edward remarried. His bride, about ten years his junior, was Anne Stanhope, the daughter of Sir Edward Stanhope and Elizabeth Bourchier. It has been suggested that Edward had his first marriage annulled to marry Anne, but there is no evidence of an annulment, and Edward’s marriage to Katherine Fillol had broken down years before, as evidenced by the reference in her father’s will to Katherine’s remaining in a house of religion. Most likely, Katherine had died in her nunnery, leaving Edward free to remarry. Sir Richard Page, Anne’s stepfather, was a fellow courtier, who like Edward had served in Henry Fitzroy’s household and accompanied the king to France in 1532, so it is possible that one of the two men proposed the match to the other. Alternatively, Anne had served Catherine of Aragon, so she and Edward may have met at court and become attracted to each other of their own volition. Regarded by contemporaries as difficult and haughty, Anne was nonetheless a loyal and apparently loving wife. By November 1537, Edward and Anne had two daughters, who were brought to visit Princess Mary; they would eventually have ten children, one of whom died young.

In September 1535, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, on a royal progress, visited Wolf Hall, the chief residence of the Seymours. As his father’s heir, Edward probably helped host the event, and while his sister Jane is not documented as being present, it seems likely that she would have been there as well, as one of Queen Anne’s ladies.

When the king started taking an interest in Edward’s sister is unknown, but by February 10, 1536, Chapuys was reporting “the treatment shown to a lady of the Court, named Mistress Semel, to whom, as many say, he has lately made great presents.”

Less than a month later, on March 3, Edward Seymour was made a gentleman of the king’s privy chamber—a position that that the late Eric Ives, in a rare moment of unkindness, suggested that he used to his advantage to act as his “sister’s ponce.” Henry, however, having interested himself in Jane, was probably quite capable of managing his new amour without brotherly assistance from Edward—as, perhaps, was Jane herself. On April 1, Chapuys reported that the king had sent Jane a purse full of sovereigns and a letter, which Jane returned to the messenger with the declaration that “she had no greater riches in the world than her honor, which she would not injure for a thousand deaths, and that if he wished to make her some present in money she begged it might be when God enabled her to make some honorable match.” As Chapuys went on to note, Henry was so impressed by this that he declared that he would speak to Jane only in the presence of her relations, to which purpose he ordered Thomas Cromwell to vacate his chambers at Greenwich in favor of Edward Seymour and his wife, so that the king could visit Jane in their presence.

Edward and his lady, of course, were not required to act as chaperones for long. Following Anne Boleyn’s arrest and execution, Henry married Jane Seymour on May 30, 1536 (not, as is often claimed, the day after Anne’s execution). A few days later, on June 5, Henry made his new brother-in-law Edward Viscount Beauchamp of Hache. On October 18, 1537, soon after Jane presented the king with a son, Henry created Edward Earl of Hertford. Nonetheless, Edward still had a long way to go in his career: in 1538 an observer, describing the various noblemen about court, declared him to be “young and wise, of small power.” A decade later, however, Edward Seymour, as Protector for his nephew, would be the virtual ruler of England.

Selected Sources

Barrett L. Beer, “Seymour, Edward, duke of Somerset (c.1500–1552),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2009.

M.L. Bush, “The Lisle-Seymour Land Disputes: A Study of Power and Influence in the 1530s.” The Historical Journal (1966).

Letters and Papers of Henry VIII.

David Loades, Jane Seymour.

October 29, 2013

Angry Monks and Bloody Weapons

Into nearly every novel about Lady Jane Grey must fall this scene: Jane and her parents, Henry and Frances Grey, Duke and Duchess of Suffolk, are strolling around their home at Sheen when a hand, wielding a bloody axe or sword, suddenly pops out of the wall, giving the family the fright of their lives and underscoring the author’s message that only bad things can be expected from Jane’s recent marriage to Guildford Dudley. As it’s Halloween week, there’s no better time to examine this story.

Sketch of Sheen Priory by Anton van den Wyngaerde, minus the bloody axe.

In nonfiction, the most recent incarnation of the story I can find is in Alison Weir’s The Children of Henry VIII, where Weir writes that while Jane and her parents were at Sheen, “a former monk, embittered at having been turned out of the foundation by Henry VIII, did his best to frighten them away. One day, when the Duke and Duchess were walking in the gallery, a bloody hand brandishing a dripping axe thrust itself out of an aperture in the wall. No sources record what happened to the monk who perpetrated this hoax.”

Weir cites no source for the story, but it appears to come from Hester Chapman’s Lady Jane Grey. Citing Agnes Strickland as her source (more on that later), Chapman writes:

Soon after the wedding Lady Jane and the Suffolks moved to Sheen, a palace on the river once belonging to Somerset, which before that had been a monastery. Some of the original occupants, no doubt incensed by the treatment they had received, were still hanging about the grounds; and eventually, hoping to drive out the Suffolk, they staged a threatening and bodeful apparition in one of the galleries. They waited till the Duke and Duchess were walking there; then, from an opening in the wall, a red hand appeared, brandishing a bloodstained axe.

It is unlikely that the Suffolks accepted this crude demonstration as it was meant. In their world, a bloody axe was too familiar an object to be regarded as either a symbol or a warning.

Leaving aside the unlikelihood that even the Suffolks, cold and unfeeling as they are depicted by Chapman, wouldn’t be nonplussed by a disembodied hand coming out of the wall, we move to the next version of the story, given to us by Richard Davey in The Nine Days’ Queen:

It was supposed to be haunted—the place was often disturbed after dark by the sound of footsteps, the rustle of ghostly garments, and the mutter of unearthly voices; but the most ghastly incident of all was one which struck sudden terror into the hearts of the Duke and Duchess as they paced the gallery in the gloaming. All at once a skeleton hand and arm thrust itself from the wall, and brandished in their faces a sword, or, as some said, an axe, dripping with blood. It should be remembered that the Lady Frances was now in possession of nearly all the Carthusian property in and about London, which had been granted by Henry VIII to her father, Charles Brandon, and which she had lately inherited from her stepbrothers; and this spectre may have been contrived by some friend of the exiled Brotherhood to impress on the Duchess and her brood the sacrilegious origin of this wealth, which certainly did not bring them good luck.

And finally, we have Agnes Strickland, writing in Lives of the Tudor and Stuart Princesses:

[Lady Jane Grey]‘s father then held possession of the Carthusian building of (East) Sheen, once belonging to the Protector Somerset—a haunted place, as report went—where he and his proud duchess were once most thoroughly terrified, when walking together in the gallery there, at a time when they were at the pinnacle of prosperity, ruling England. Suddenly, out of the wall issued a hand, bestained with red, brandishing a bloody sword, or, as some say, an axe, in their faces. As both the duke and duchess saw this apparition, and were well-nigh terrified to death, it was, in all human probability, an ocular deception contrived by some one interested in the ejected Carthusian occupants.

So where did Agnes Strickland derive this story? She gives no source, and I have not been able to trace it past her. It seems most probable that Strickland was repeating a colorful legend that came to her ears.

But there is one feature in the story that up until now, I believe, has gone unremarked. Which duke and duchess saw the apparition–Lady Jane Grey’s parents or their predecessors at Sheen, Edward and Anne Seymour, the Duke and Duchess of Somerset? The antecedent of “he and his proud duchess” in Strickland’s account is not clear, but the reference to the couple being “at the pinnacle of prosperity, ruling England” suggests that Somerset, Edward VI’s Protector from 1547 to 1549, and his wife were the strolling couple in question. Henry Grey, a political lightweight, could hardly be described as “ruling England” at any time in his career. As for the “proud duchess,” while this could refer to Frances Grey, niece of Henry VIII, it is far more likely here to be a reference to Anne, Duchess of Somerset, for in this book, Strickland repeatedly couples the duchess’s name with the epithet of “proud”:

“Newdigate, the husband of the proud Duchess of Somerset . . .”

” . . . the proud old duchess to goad Cecil with her solicitations for Hertford and Katharine . . .”

“Anne Stanhope, the proud Duchess of Somerset . . .”

By contrast, Strickland doesn’t bestow a single “proud” upon Frances when referring to her by name. Furthermore, given the fact that Henry VIII bestowed the former Carthusian priory of Sheen on Edward Seymour back in the 1540′s, it seems rather unlikely that its former occupants would still be playing ghostly tricks in 1553.

Thus, it appears that all of these years, writers misreading Strickland’s admittedly murky prose have been erroneously depicting the hapless Duke and Duchess of Suffolk as being scared out of their wits by a protruding hand, when in fact it was the Duke and Duchess of Somerset who were spooked by the ghastly apparition. Perhaps in future iterations of the story, the Somersets will be restored to their rightful place in the annals of ghost-spotters.

October 21, 2013

Warwick the Matchmaker

The Victorian historian Agnes Strickland was a pioneer in writing about historical women, and deserves due credit for this. That being said, Strickland also perpetuated some historical howlers, one being a misreading which led to her creating a stepmother for Anne Boleyn, whose own mother was very much alive and married to her father. This humble, self-effacing, and nonexistent stepmother has even acquired a niche in historical fiction, being made a character in several well-known novels about Anne.

In addition to the queen’s stepmother, Agnes Strickland (with help from James Halliwell, who found the letters in question) also created a suitor for the hand of young Elizabeth Woodville: the lovelorn Hugh John (or, to use the Welsh spelling, Johnys). As Strickland tells it, the gallant, but star-crossed, Hugh Johnys enlisted two very important friends to aid his suit, both of who wrote to Elizabeth Woodville on his behalf. First, Richard, Duke of York did his part:

Right trusty and well beloved, we greet you well; And for so much as we are credibly informed that our right hearty and well-beloved knight, Sir Hugh John, for the great womanhood and gentleness approved and known in your person, your being soul and to be married, his heart wholly have, whereof we are right well pleased. How it be of your disposition towards him in that behalf as yet to us is unknown, we, therefore, as for the faith, true and good lordship we owe unto him at this time, and so will continue, desire and heartily pray you will on your part be to him well willed to the performing of this our writing and his desire. Wherein you shall do not only to our pleasure, but we doubt not to your great weal and worship in time coming. Certifying you, if you fulfill our intent in this matter, we will and shall be to him and you such lord as shall be to your both great weal and worship by the grace of God, who precede and guide you in all heavenly felicity and welfare.

Richard, Earl of Warwick, followed with an even more eloquent appeal to the heart:

Worshipful and well beloved, I greet you well, And for as much as my right well beloved, Sir Hugh John, knight, which now late was with you unto his full great joy, and had great cheer as he sayeth, whereof I thank you, hath informed me how that he for the great love and affection that he hath unto your person, as well for the great sadness [seriousness] and wisdom that he found and proved in you at that time, as for your great and praised virtues and womanly demeaning, desireth with all his heart to do you worship by way of marriage, before any other creature living as he sayeth. I, considering his said desire, and the great worship that he had, which was made knight at Jerusalem; and after his coming home, for the great wisdom and manhood that he was renowned of, was made knight Marshal of France, and after that knight Marshal of England, unto his great worship, with other his great and many virtues and deserts; And also the good and notable service that hath done and daily doth to me, Write unto you at this time, and pray you effectuously that you will the rather, at this my request and prayer, to condescend and apply you unto his said lawful and honest desire, wherein you shall not only purvey right notably for yourself unto your weal and great worship in time to come, as I verily trust, but also cause me to show unto you such good lordship, as you by reason shall hold you content and pleased, with the grace of God, which everlastingly have you in his blessed protection and governance.

Unfortunately, York’s and Warwick’s letters (which are undated) turn out to have been addressed not to Elizabeth Wodevile (with a “v”) but to Dame Elizabeth Wodehill (with an “h”). Although Halliwell’s 1842 transcript of the letters gives the “Wodehill” spelling, the significance of this escaped him and Strickland; indeed, the latter dismissed the discrepancy as a mere slip of the pen. As later historians realized, however, there was indeed a Dame Elizabeth Wodehill, a widow of means in Northamptonshire, and it was she, not young Elizabeth Woodville, who was the object of Sir Hugh’s suit.

The daughter of Sir John Chetwode, Elizabeth Wodehill was the widow of Sir Thomas Wodehill, who died in 1421. She subsequently married William Luddesop, a social inferior, who died in 1454. It was probably after her second husband’s death when Dame Elizabeth was solicited to marry Hugh Johnys, a Welshman connected with the Vaughan family. His monumental brass at Swansea confirms York’s account of his career: Knighted in Jerusalem in 1441, he fought against the Turks and the Saracens in Troy, Greece, and Turkey, served in France under John, Duke of Somerset (father to Margaret Beaufort), and later served John, Duke of Norfolk, as knight marshal. In 1451, he had a wife, Mary, who died, leaving Hugh to court Dame Elizabeth.

Alas, Warwick the Kingmaker, as he was called by later generations, was not Warwick the Matchmaker. Despite his and York’s intervention, Dame Elizabeth apparently refused Sir Hugh’s suit. Perhaps, as W. R. B. Robinson has suggested, the political situation at the time (probably in the mid-1450′s) made the lady wary of connecting herself too closely with a follower of York and Warwick; alternatively, being comfortably off, and no longer young, she may have simply preferred the independent life of a widow to marriage. She died in 1475, having never taken a third husband, and was buried at Warkworth Church.

Happily for the spurned Hugh Johnys, he did not pine away for love, but consoled himself with Maud Cradock (whose first cousin Sir Mathew later married Lady Catherine Gordon, the widow of the pretender Perkin Warbeck). He was in favor with York’s son Edward IV, who appointed him in 1468 as a Poor Knight of Windsor, which entitled him to lodgings at Windsor Castle and required him to pray for the king and the Knights of the Garter at St. George’s Chapel. Apparently through a connection with William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, Hugh also seems to have been involved in the military training of young Henry Tudor, who just a few weeks after becoming king gave him ten pounds for the good service that Johnys had rendered him in his “tender age.” The date of his death is unknown, but he was survived by five sons and four daughters; one of his sons, Robert Jones, served both Henry VII and Henry VIII. For a man who never wooed Elizabeth Woodville, and never won Elizabeth Wodehill, Hugh could nonetheless congratulate himself on a long and eventful life.

Sources:

William Campbell, Materials for a History of the Reign of Henry VII, vol. 1.

J. O. Halliwell, “Observations upon the History of Certain Events in England during the Reign of King Edward the Fourth,” Archaeologia (1842).

W. R. B. Robinson, “Sir Hugh Johnys: A Fifteenth-Century Welsh Knight,” Morgannwg (1970).

Agnes Strickland, Lives of the Queens of England.

October 12, 2013

The Myth of the Cousins’ War: A Guest Post by Leanda de Lisle

A hearty welcome to Leanda de Lisle! As I said in my last post, I thoroughly enjoyed her new book, Tudor: The Family Story. And now, here is Leanda:

The Wars of the Roses are so over. The power struggle between the red rose House of Lancaster and the white of York, has a new, and supposedly more ‘authentic’, name. Philippa Gregory, Sarah Gristwood and Alison Weir, have relabelled the era ‘the Cousins War’. They tell us this was the term used by contemporaries. But we are never told who these contemporaries were or where they used it. So which is the more ‘authentic’ term?

When I wrote my new dynastic history, ‘Tudor’ I believed that ‘the Wars of the Roses’ was a term first coined by the nineteenth century novelist Sir Walter Scott. The historian Dan Jones has since traced these exact words back to the eighteenth century historian David Hume. But as I note in Tudor, the origins of the phrase are much older than the form of words we now use.

The ‘wars of the roses’ were being referred to as ‘the quarrel of the two roses’ in the mid seventeenth century Before then you have Shakespeare’s play Henry VI, part I, with the scene in which Richard, Duke of York quarrels with the Lancastrian leader, Edmund, Duke of Somerset. The two men ask others to show their respective positions by picking a rose – red for Lancaster and white for York.

The simple five-petal design of the heraldic rose of the fifteenth century was inspired by the wild dog rose that grows in English hedgerows, and was used in different colours. The earliest association I found linking a red rose with the House of Lancaster was when Henry Bolingbroke – the future Henry IV, and first king of the House of Lancaster, had red roses decorating his pavilion at a joust in 1398.

At the height of the Lancastrian struggle with the House of York, the red rose appears again in a striking context. The deposed Lancastrian Henry VI was re-adapted briefly as king in 1470, and the Grocer’s Company in London planted red roses as a mark of their loyalty to him. Although the red rose was not a favourite Lancastrian badge, it marked a contrast with the white rose badge used by Henry VI’s enemy and rival, Edward IV of the House of York – the Grocer’s Company had ripped up white roses, to plant the red.

Detail of a Tudor rose, from British Library Royal 20 E III f. 30v.

In 1485 Henry Tudor chose the red rose as his favoured badge in the knowledge that he was to marry Elizabeth of York, the heir of the white rose dynasty. Within weeks of this marriage the royal mint had issued a coin featuring the double union rose, commonly termed the ‘Tudor rose’, in which the red petals of the Lancastrian rose, surround the white petals of the House of York. It became immensely popular with artists and poets, symbolising as it did, national healing after the civil wars.

Does the term ‘the Cousins war’ really have the same meaning or resonance? Certainly the House of Lancaster and York were cousins, the two families being descended from Edward III. But as royal houses intermarry, and as European nations were ruled by monarchies for most of their history, half the wars in Europe’s past could be described as ‘cousins wars’ – down to and even including World War I.

Should we really edit out the Wars of the Roses for a term as dull and woolly as ‘the Cousins war’? Does it actually have any history predating the works of Gregory, Gristwood and Weir? And in what way is it more authentic?

October 7, 2013

New Books!

Good morning! I wanted to start out by mentioning that Leanda de Lisle’s excellent nonfiction book, Tudor: Passion. Manipulation. Murder. The Story of England’s Most Notorious Royal Family is now on sale, both here in the United States and in the UK (under the title Tudor: The Family Story). I was fortunate enough to read it a couple of weeks ago, and I found it to be excellent. It was particularly nice to see attention paid to the often-neglected early Tudors: Owen, his sons, and his grandson Henry VII.

I also wanted to mention (naturally) that my first nonfiction book, The Woodvilles, published by The History Press, is now available on Kindle (and in other electronic formats as well). The hardback book will be published in the UK shortly (January in the US). In honor of the occasion, I’ll be doing some guest blog posts this month. My first stop is at the Lady Jane Grey Reference Guide, where I have a post about Thomas Grey, Marquis of Dorset, Elizabeth Woodville’s eldest son by her first marriage. On Thursday, I’ll be stopping by Queen Anne Boleyn Historical Writers with a post about Anthony Woodville. Hope to see you there!

September 16, 2013

Eleanor Cobham: The Duchess and her Downfall

The following is a guest post I did last year for the lovely Melanie Clegg, a historical novelist whose latest book, Minette, is high on my to-be-read list. Melanie has a great blog–do stop by!

For a few years in the fifteenth century, Eleanor Cobham, Duchess of Gloucester—an adulteress and the daughter of a mere knight—was within a heartbeat of becoming queen of England. Instead, she ended her life a prisoner, bereft of her wealth and forcibly divorced from the man who had brought her to the pinnacle of English society.

Eleanor was a daughter of Sir Reginald Cobham of Sterborough and his first wife, Eleanor Culpepper. In the early 1420’s, she entered the household of Jacqueline, Countess of Hainault, who had taken refuge in England in 1421 after repudiating her husband John, Duke of Brabant.

Henry V, the English king, died in August 1422, leaving his infant son, Henry VI, as his successor. Henry V’s younger brother, John, Duke of Bedford, governed in France, while his youngest brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, was named protector of England during the young king’s minority.

Jacqueline’s cause of recovering Hainault from her estranged husband and of recovering Holland and Zeeland from her uncle, John of Bavaria, attracted a powerful supporter, Duke Humphrey. Her person may have attracted him as well, for by February 1423, Duke Humphrey and Jacqueline had married. In October 1424, the pair landed at Calais. Eleanor, as a member of Jacqueline’s household, accompanied them.

What ensued was not Duke Humphrey’s most shining moment. Though Humphrey managed to recover much of Hainault, he soon met a determined opponent in Philip, Duke of Burgundy, who himself advanced into Hainault in March 1425. Humphrey had never been a popular figure in Hainault, and with the locals turning their support toward Burgundy, he decided to give up his adventure abroad. Probably he was also worried about what moves might be made against him in England during his absence. In April 1425, then, Humphrey departed for England, leaving his wife Jacqueline to fend for herself. He would never see her again.

Also returning to England was Eleanor, said by the chronicler Jean de Waurin to not wish to stay any longer in foreign parts. Described by Aeneas Sylvius as “a woman distinguished in her form,” and by Waurin as “beautiful and marvelously pleasant,” Eleanor soon became Humphrey’s mistress. Later, it would be claimed that Eleanor employed the witch Margery Journemayne to prepare drinks and medicines to induce the duke to “love her and to wed her.”

Jacqueline, meanwhile, doggedly continued to fight for her rights while awaiting the results of a papal inquiry into the validity of her marriages. Humphrey had not abandoned her entirely. In 1427, the king’s council allotted 9,000 marks for him to return to Hainault with an army, but the Duke of Bedford, fearing the consequences of such an action, intervened and brought Humphrey’s rather half-hearted preparations to a standstill by entering into negotiations with the Duke of Burgundy. More bad news for Jacqueline followed in January 1428, when the Pope ruled that her marriage to Duke Humphrey was invalid.

Eleanor’s relationship with Humphrey had not gone unnoticed. Sometime between Christmas 1427 and Easter (20 April ) of 1428, a group of women from London, “of good reckoning, well appareled,” came to Parliament, where, the chronicler Stow later reported, they delivered letters to Humphrey, the archbishops, and other lords “containing matter of rebuke and sharpe reprehension of the Duke of Gloucester, because he would not deliver his wife Jacqueline out of her grievous imprisonment, being then helde prisoner by the Duke of Burgundy, suffering her to remaine so unkindly, and for his public keeping by him another adulteresse, contrary to the law of God and the honourable estate of matrimony.” Their complaints had no effect on Humphrey. He could have remarried Jacqueline despite the papal ruling, as her first husband was dead. Instead, he married Eleanor Cobham, to general opprobrium.

It is not clear how long Eleanor and Humphrey had been lovers before their marriage. Humphrey had two illegitimate children, Arteys de Cursey (otherwise known as Artus or Arthur) and Antigone, who later married Henry Grey, Earl of Tankerville. It has been speculated by many, including Humphrey’s biographer K.H. Vickers, that Eleanor was the mother of these two children, but this seems unlikely. If Eleanor was indeed their mother, it is hard to imagine why Humphrey, who had no legitimate children, did not attempt to legitimatize Arteys and Antigone after his marriage to Eleanor, as John of Gaunt had legitimized his children by Katherine Swynford after he made her his duchess. Furthermore, Eleanor was later to confess to employing witchcraft in order to bear a child by Humphrey—an odd statement if she was already the mother of two of his children. It is also notable that after the deaths of her father and of Henry Grey, Antigone left England and married Jean d’Amancier, esquire of the horse to King Charles VII of France, which suggests that she had connections in France, presumably through her mother.

On 25 June 1431, Eleanor was admitted into the fraternity of the monastery of St. Albans, of which her husband was already a member. The following year, she joined an even more select group: the ladies’ fraternity of the Order of the Garter. Her Garter robes were awarded on 26 March 1432. Later, in 1440, the king gave her a New Year’s gift of a “Garter of Gold, barred through with bars of Gold, and this reason made with Letters of Gold thereupon, hony soit qui mal y pense, and garnished with a flower of Diamonds on the Buckle, and two great Pearls and a Ruby on the Pendant and two great Pearls with twenty-six Pearls on the said Garter.”

Eleanor’s status underwent a drastic change in September 1435, when the Duke of Bedford, Humphrey’s older brother, died. As the fourteen-year-old Henry VI was childless, and Bedford had no legitimate children from either of his two marriages, Humphrey now stood next in line to the throne. The king gave Eleanor fine New Year’s presents to match her status. In 1437, her gift from Henry VI was “a nouche maad in mane of a man garnized with a fayre gret bal” and with a “gret diamand pointed with thre hangers garnized with rub . . . bought of Remonde goldesmyth.” Even Eleanor’s father benefited: the high-ranking Charles, Duke of Orleans, who had been taken prisoner by the English at Agincourt, was transferred into his custody.

Eleanor was in her glory — and knew it. Ralph Griffiths reported, “One chronicler noted how she flaunted her pride and her position by riding through the streets of London, glitteringly dressed and suitably escorted by men of noble birth.” She was even accused of extortionate practices against the almsmen of the Hospital of St. John at Pontefract.

For all of his faults, Duke Humphrey was a cultured and intelligent man, with a love of books, and it is likely that Eleanor shared his interests. She is said by Vickers to have owned Sloane MS 248, described by him as a “semi-medical, semi-astrological work translated from the original Arabic.” And it was Eleanor’s interest in astrology that would prove to be her downfall.

On either 28 June or 29 June 1441, Eleanor, dining in her usual high style at the King’s Head in Cheapside, heard of the arrests of three of her associates, Master Roger Bolingbroke, an Oxford priest who also served as Eleanor’s clerk, Master Thomas Southwell, a canon and a rector, and John Home, a canon who also served as Eleanor’s chaplain and secretary. The three men were accused of conspiring to bring about the king’s death.

Bolingbroke had once composed a tract for his “esteemed and most reverend lady [probably Eleanor], in the mother tongue, concerning the principles of the art of geomancy.” Now he apparently implicated her, stating that she had commissioned him to predict her future— not a trivial manner for a woman whose husband was next in line to the throne. Soon he and Southwell would be indicted for sorcery, felony, and treason. Bolingbroke was accused of having contacted demons and other malign spirits, and he and Southwell were both accused of having used astrology, with Eleanor’s encouragement, to predict the king’s death in the twentieth year of his reign. A nervous Henry VI promptly commissioned an alternative horoscope, which neatly refuted the horoscope drawn by Bolingbroke and Southwell. (If the new astrologer, whose identity is not known, had learned that Henry would live another thirty years, but would die as a prisoner in the Tower of London, probably through foul play, he wisely omitted this prognostication.)

Eleanor, meanwhile, had fled into sanctuary. On 24 and 25 July, she was examined at St. Stephen’s Chapel, Westminster, on twenty-eight charges. J.G. Bellamy points out that as she appeared before ecclesiastical instead of secular authorities, she was likely being investigated for heresy and witchcraft instead of treason; the lack of precedents for trying a peeress for felony and treason probably saved her from such charges. Eleanor admitted five of the charges, the precise details of which have not survived.

It was probably at this point that Eleanor acknowledged using the services of Margery Jourdemayne, known as “the witch of Eye.” Margery, from a yeoman family, had already been imprisoned for witchcraft; in 1432, she had been released on good behavior. Jessica Freeman suggests that since that time, she had continued to discreetly offer clients love potions and charms, such as those allegedly used by Eleanor to entice Humphrey into marriage.

Meanwhile, Eleanor had been ordered to await future hearings at Leeds Castle. Fearful of leaving sanctuary, she feigned sickness and attempted to escape by water, but was found out. On 11 August, she was escorted to Leeds by members of the king’s household. Eleanor remained at Leeds for the next two months. On 19 October, she returned to Westminster, where she was again examined by an ecclesiastical tribunal at St. Stephen’s. At a second hearing on 23 October, she was confronted with Bolingbroke and his instruments, and admitted to employing them only to conceive a child by Humphrey. Southwell and Margery also appeared at the hearing, where they accused Eleanor of being the “causer and doer of all these deeds.” She was found guilty of sorcery and witchcraft.

While imprisoned in the Tower, Southwell escaped his probable fate by dying “of sorrow” on 26 October; Freeman suggests that he might have taken poison in order to escape the death of a traitor. The next day, Margery, who had been found guilty of heresy and witchcraft, was burned at Smithfield. Bolingbroke, found guilty in a trial before the King’s Bench, was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn on 18 November. Home, who had been indicted only for having knowledge of the activities of the others, was pardoned and continued in his position as canon of Hereford. He died in 1473.

What was Humphrey doing while all of this was unfolding? Over the past couple of years, his differences with the king’s other advisers over foreign policy and the rise of other men in the king’s favor, especially William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, meant that he had become increasingly marginalized. There was little he could do to assist his wife. Perhaps he was also shocked at her activities, in which he had not been implicated. As Vickers points out, though, he may not have been entirely passive, as an edict was issued forbidding interference in the proceedings against Eleanor, and she was heavily guarded on her trip to Leeds.

Whatever protection the duke could have offered his wife ended on 6 November 1441, when a commission of bishops ordered that Humphrey and Eleanor be divorced. The couple would never meet again.

Three days later, Eleanor was ordered to do public penance for her sins. On 13 November, bareheaded and dressed in black, carrying a wax taper, she was taken by water from Westminster to the Temple landing stage. Led by two knights, she walked from Temple Bar to St. Paul’s Cathedral, where she offered her taper at the high altar. Two days later, she walked from the Swan pier in Thames Street to Christ Church, where she again offered a taper. On 17 November, with the familiar taper in hand, she made a third journey, from Queenhithe to St. Michaels in Cornhill. The citizens, plenty of whom were on hand to witness her humiliation, had been ordered neither to show her respect nor to molest her.

Edwin Abbey’s depiction of Eleanor’s penance

Her public penance ended Eleanor’s public life. In January 1442, she was sent to Cheshire; the king, evidently bearing Eleanor’s previous feigned illness in mind, ordered that the journey not be delayed due to any sickness on her part. She was allowed 100 marks per year and had a household of twelve people—a considerable comedown for the proud duchess. In October 1443, she was taken to Kenilworth; during her stay there, King Henry sent her a canopy with curtains for her bed. In July 1446, Eleanor was transferred to the Isle of Man. In March 1449 she moved for the last time, to Beaumaris in Wales. On 7 July 1452, she died at Beaumaris, where she was buried at the expense of Sir William Beauchamp, the constable of the castle there. Few chroniclers noted her demise, and it was not until 1976 that her date and place of death were established.

Humphrey did not long survive his wife’s disgrace. In February 1447, he set off for a meeting of Parliament at Bury St. Edmunds. One chronicler wrote that he hoped to obtain a pardon for his imprisoned wife. Instead, he was arrested, for reasons too complicated to go into here. He died several days later on 23 February, probably of a stroke, although murder was rumored. A number of his retainers, including his illegitimate son, were arrested and convicted of treason, but were pardoned immediately before they were to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Among the charges against them was that they had been attempting to free Eleanor Cobham.

The Duke of Gloucester was buried at St. Albans, and, thanks largely to the unpopularity of Henry VI’s ministers, soon acquired a posthumous reputation as “Good Duke Humphrey.” As for Eleanor’s legacy, it would be to add a footnote to legal history. In 1442, Parliament cleared up the question of how peeresses charged with treason or felony were to be tried by enacting a statute declaring that just like peers, they would be judged by the judges and peers of the realm.

Eleanor, of course, was one of several prominent ladies who would be accused of witchcraft in the fifteenth century. The next would be Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford, Eleanor’s erstwhile sister-in-law.

(For lovers of historical fiction, Eleanor Cobham is one of the subjects of Jean Plaidy’s Epitaph for Three Women. She is also featured in Claude du Grivel’s Shadow King, which I haven’t read. Humphrey and his family feature in Juliet Dymoke’s Lord of Greenwich and in Brenda Honeyman’s Good Duke Humphrey. Jacqueline is the heroine of Hilda Lewis’s I, Jacqueline.)

Sources:

J. G. Bellamy, The Law of Treason in England in the Later Middle Ages. Cambridge: 1970.

Hilary M. Carey, Courting Disaster. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

Jessica Freeman, “Sorcery at Court and Manor: Margery Jourdemayne, the Witch of Eye next Westminster.” Journal of Medieval History, 2004.

James L. Gillespie, “Ladies of the Fraternity of Saint George and of the Society of the Garter.” Albion, 1985.

Ralph A. Griffiths, King and Country: England and Wales in the Fifteenth Century. London: Hambledon Press, 1991.

G. L. Harriss, ‘Eleanor , duchess of Gloucester (c.1400–1452)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008.

Harris Nicolas, Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council of England, 15 Henry VI to 21 Henry VI, vol. V. 1835.

Ruth Putnam, A Mediaeval Princess. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904.

K. H. Vickers, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. London: Constable and Company, 1907.

September 7, 2013

The Indomitable Duchess: Alice Chaucer, Duchess of Suffolk

[This post was originally done as a guest post for Sarah's History Blog. Sarah can now be found blogging at her excellent Henry III blog.]

Detail from upper effigy of Alice’s tomb (a cadaver effigy is below it)

In what would prove to be his last letter, William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, preparing to sail off into exile, wrote a letter to his young son, John, in which he advised the boy “always, as ye be bound by the commandment of God to do, to love, to worship your lady and mother, and also that you always obey her commandments, and to believe her council and advice in all your works, the which dreadeth not, but shall be best and truest to you.” The woman of which Suffolk spoke so highly was his duchess, Alice Chaucer.

A granddaughter of the poet Geoffrey Chaucer, Alice was born around 1404, probably at the manor of Ewelme in Oxfordshire, and was the only child of Thomas Chaucer and Maud Burghersh. She never met her famous grandfather, who died in 1400. Her wealthy and well-connected father, who served several times as Speaker of the Commons, arranged her marriage early: by October 1414, Alice was the wife of Sir John Phelip, a wealthy knight who was nearly twenty-five years her senior. A year later, on October 2, 1415, Sir John died at the siege of Harfleur, a victim not of a French arrow but of the flux.

By 1424, and perhaps as early as 1421, Alice had made an even better marriage than her first. This time, her groom was Thomas Montague, Earl of Salisbury, a widower. Born in 1388, Salisbury was one of the best and most experienced English commanders in France, where Alice spent part of her married life. There, at a wedding celebration in November 1424, she is said to have aroused the lust of Philip, Duke of Burgundy. Furious about this, the story goes, Salisbury became an implacable enemy of the amorous Burgundy.

Whatever the truth of this tale, it does not seem to have lessened Salisbury’s good opinion of Alice. In his will, he referred to her as his “beloved wife,” and asked that his tomb at Bisham Abbey be designed so that his first wife could lie on one side and Alice, “if she will,” on the other. Alice, however, would make other burial plans for herself.

On October 27, 1428, Salisbury, who was besieging Orléans, was watching the city from a window at Les Tourelles when he was struck by debris from a cannonball, which tore away much of his lower face. For a week, he lingered before dying at Meung on November 3. He and Alice had had no children, although the earl himself had a daughter (also named Alice) by his first wife as well as an illegitimate son. Alice Chaucer served as the supervisor of her husband’s will. He left her half of his net goods, 1,000 marks in gold, and 3,000 marks in jewellery and plate, as well as the revenues of his Norman lands as long as they could be collected.

William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, took up Salisbury’s command in France. Two years after Salisbury’s death, Suffolk took over his widow as well: on November 11, 1430, he and Alice were issued a royal license to marry.

Born in 1396, Suffolk had spent most of his adult life serving in France. He had been taken prisoner at Jargeau, by forces led by Joan of Arc, in 1429, and was set free in early 1430. From that point on, his career would center around the court of Henry VI and his and Alice’s estates in East Anglia and the Thames Valley.

As her husband became a prominent figure at court, so did Alice. In 1432, she was made a Lady of the Garter. In the autumn of 1444, she accompanied her husband to France to escort Henry VI’s bride, Margaret of Anjou, to England. When Margaret, traveling through English-occupied France, fell ill in March 1445, Alice, dressed in the queen’s robes, took her place in the ceremonial entry into Rouen. By this time, Alice was the Marchioness of Suffolk, as William had been made a marquis on September 14, 1444, for his role in arranging the king’s French marriage.

An odd incident involving Alice and one of Suffolk’s prominent supporters, Sir Thomas Tuddenham, dates from before June 1448, when William was made Duke of Suffolk. As rendered in modern English by Susan Swain Madders, officials of the city of Norwich complained:

It was so, that Alice, Duchess, that time Countess of Suffolk, lately in person came to this city, disguised like a country housewife. Sir Thomas Tuddenham, and two other persons, went with her, also disguised; and they, to take their disports, went out of the city one evening, near night, so disguised, towards a hovel called Lakenham Wood, to take the air, and disport themselves, beholding the said city. One Thomas Ailmer, of Norwich, esteeming in his conceit that the said duchess and Sir Thomas had been other persons, met them, and opposed their going out in that wise, and fell at variance with the said Sir Thomas, so that they fought; whereby the said duchess was sore afraid; by cause whereof the said duchess and Sir Thomas took a displeasure against the city, notwithstanding that the mayor of the city at that time being, arrested Thomas Ailmer, and held him in prison more than thirty weeks without bail; to the intent thereby both to chastise Ailmer, and to appease the displeasure of the said duchess and Sir Thomas; and also the said mayor arrested and imprisoned all other persons which the said duchess and Sir Thomas could understand had in any way given favour or comfort to the said Ailmer, in making the affray. Notwithstanding which punishment, the displeasure of the duchess and Sir Thomas was not appeased.

Because of this and other incidents, the city claimed, the crown had seized its franchise. Sadly, we have only the city’s version of events, not Alice’s. Nor do we know what Suffolk thought of his wife “disporting” herself with Tuddenham (who would be executed in 1462 by Edward IV). Perhaps Tuddenham’s odd marital history—his only marriage had been dissolved for lack of consummation, although his wife gave birth to a child by her father’s chamberlain—made him above suspicion.

As this incident shows, Alice was not a popular figure in Norwich, and matters were to get much worse. By the late 1440’s, English reversals in France and rivalries in East Anglia combined by the late 1440’s to make Suffolk one of the most hated men in England. Accused by the Commons of treason charges which included plotting with the French and attempting to put his own son on the throne, he was imprisoned in the Tower in 1450. Henry VI attempted to save his chief minister and pacify his enemies by sending him into exile. He left Ipswich on May 1.

Sailing into the Straits of Dover, Suffolk’s pinnace was intercepted by a larger vessel named Nicholas of the Tower, the crew of which forced Suffolk to leave his own ship and board theirs, where he was met with cries of “Welcome, traitor!” After a mock trial, he was condemned to die and was allowed to spend the evening preparing for death with his chaplain. The next morning, Suffolk was hustled onto a smaller boat, where he was beheaded with six strokes of a rusty sword. Suffolk’s head and body were rowed to the shore of Dover, where they were tossed on to the sand.

Alice had not followed Suffolk into exile but had stayed home in England, presumably to run the couple’s estates. With her was the couple’s only surviving child, John, born on September 27, 1442. It was to John that Suffolk had addressed the farewell letter urging his seven-year-old son to be guided by his mother. Suffolk also made his regard for Alice manifest in his will, written on January 17, 1450. In it, he named Alice his sole executrix, “for above all the earth my singular trust is most in her.”

To get through the next months, Alice would need all of the comfort her murdered husband’s trust in her could give. Throughout the summer and autumn of 1450, and over the next two years, poachers repeatedly raided her parks—and that was the least of her problems. After Suffolk’s murder, the unrest in Kent exploded into what is known as Jack Cade’s Rebellion. Alice was one of the rebels’ targets. When the rebels entered London in July 1450, they forced members of a commissioner of oyer and terminer to indict a number of supposed traitors, Alice among them. It is unknown what charges were pressed against Alice, but it seems likely that they were connected with the marriage of her son, John de la Pole, to the equally young Margaret Beaufort, daughter of the deceased John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset. One of the charges against Suffolk had been that he was planning to proclaim Margaret as the childless king’s heir and make his own son king through this marriage.

Alice was probably safe at one of her own manors, or perhaps with the queen, during Cade’s rebellion, but the news coming out of the city, which included the rebels’ murder of at least five men, must have deeply shaken her. Even after the crisis of the rebellion passed, she found herself the target of popular hatred. This time, in the parliament that convened in November 1450, the Commons brought a petition that certain persons be banned from coming into the king’s presence. Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, headed the list; Alice was second. An attempt was also made to attaint the dead Duke of Suffolk as a traitor, which would have prevented his son from inheriting his estates. Fortunately for Alice, the king resisted both petitions. It probably helped a great deal that on October 8, 1450, Alice lent the crown 3,500 marks toward the war effort in France.

Yet Alice’s problems were still not over, for sometime before March 1451 Alice was tried for treason before the assembled lords—perhaps on the indictment that had been brought in July. Little is known of Alice’s trial or other state trials that were held at this time, probably, as John Watts points out, because the defendants, including Alice, were acquitted.

With this crisis over, and the Suffolk estates secure, Alice’s life returned to normal. In 1453, Alice was among the great ladies summoned to attend the churching of Margaret of Anjou, who had at last borne Henry VI a son, Edward of Lancaster. In 1455, as constable of Wallingford Castle, an office she held jointly with her son, she was entrusted with a state prisoner: the troublesome Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter. The rebellious son-in-law of Richard, Duke of York, Exeter had been taken into custody following the Yorkist victory at St. Albans in 1455.

In early 1453, the marriage of John de la Pole and Margaret Beaufort was dissolved, apparently at the initiative of the king, who gave Margaret’s wardship to his half-brothers, Jasper and Edmund Tudor. Perhaps the king was also coming under pressure by those who still feared a Suffolk-Beaufort marriage; ironically, it would be Margaret’s next marriage, to Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond, that would have momentous consequences in 1485.

As the nobility began to divide in support of the houses of either Lancaster or York, Alice made a decision that would prove most fortunate. She held her son’s wardship and marriage, in an age where the wardships of wealthy young heirs were hot commodities, and in 1458, she and Richard, Duke of York, entered into an agreement for John de la Pole to marry Elizabeth, one of York’s daughters. It has been suggested that she might have become alienated from the crown because of the dissolution of her son’s first marriage, but it is just as likely that she simply saw the opportunity for an advantageous match. Whatever her motivations, her decision would prove to be a wise one, for in 1461, York’s son, Edward IV, sat on the throne of England.

During her long widowhood, Alice proved herself to be adept at looking after her and her son’s interests—even predatory. Singly or with her son, she seized the manors of Cotton, Dedham, Hellesdon, and Drayton from the Paston family, despite a claim to them that was dubious or nonexistent. Such actions do not show the duchess in an attractive light, but any sign of weakness would have left her vulnerable to the machinations of others. Colin Richmond has suggested that she was partly motivated by devotion to the memory of her husband, who had coveted the manors himself. (Suffolk had sold Cotton, his birthplace, to pay his ransom to the French and had regretted the sale.) If this is so, it makes her actions a little more palatable, although certainly the Pastons did not see it that way. Margaret Paston had good reason to advise her son not to approach the duchess without his counselors, on the ground that the duchess was “subtle and has subtle counsel with her.”

There was another side to the duchess, however. After the murder of her husband, she never remarried, but may have taken a vow of chastity. This could have been a device to avoid having a political marriage thrust upon her, but it could also be a token of her affection for her murdered husband. She donated books and gold to Oxford University, and contributed twenty pounds toward the construction of its divinity school. In 1454, she donated twenty marks to Eye Church for the construction of a tower; the donation was for the good of Suffolk’s soul and for her son’s good estate. Having moved Suffolk’s body from Wingfield, its original burial spot, to the Charterhouse at Hull, where Suffolk had requested burial in his will, Alice arranged with the prior there to have two paupers fed daily. The prior was also to erect two stone images of Alice and Suffolk, holding in the right hand a disk as a symbol of bread and fish and in the right hand an ale pot.

The most famous—and most enduring—act of piety associated with the Duke and Duchess of Suffolk is God’s House at Ewelme, founded by the couple in 1437. God’s House was an almshouse for thirteen paupers; later, the duke and duchess added a school. The foundation survives today as the Ewelme Trust; the almshouse and school are still used for their original purposes.

The almshouses erected by William and Alice

Alice was also a bibliophile. She may have commissioned the poet John Lydgate’s The Virtues of the Mass. A 1466 inventory made when Alice was moving her goods from Wingfield to Ewelme shows that she owned a number of books. Fourteen were religious texts of the sort that would be used in her chapel, but seven others, in English, French, and Latin, were clearly for Alice’s own use. The Latin book, for “the moral instruction of a prince,” was likely acquired for the education of Alice’s son. The others included Christine de Pizan’s Livre de la Cité Des Dames, and the Ditz de Philisophius, which Anthony Woodville later translated for William Caxton’s press. On one occasion, Alice worried that her books might be damaged in the place where she had left them and ordered her servant to move them to a safer location.

The upheavals of 1469 to 1471 seem to have affected Alice little. In 1472 at Wallingford, she played host to a reluctant guest—Margaret of Anjou, who had been taken prisoner by the victorious Yorkist forces after the battle of Tewkesbury. Alice had headed the entourage of ladies who escorted the young Margaret to England; now Alice was the custodian of the woman she had once served.

Alice did not live to see Margaret return to her native land in 1476. Aged about seventy-one, Alice died in May or June of 1475. Her will does not survive, but it seems likely that her unusual tomb at the church of St. Mary the Virgin at Ewelme was made to her own specifications. It contains an upper effigy of Alice, who wears the coronet of a duchess and who has the Order of the Garter wrapped around her left arm. In its day, the effigy was painted. Below the upper effigy is an enclosed cadaver effigy, showing the naked, shriveled corpse of Alice lying in an opened shroud. John Goodall notes that it is the only life-sized female cadaver sculpture in England to have survived intact.

While many medieval monuments have been lost to us, Alice’s tomb can still be seen in its glory today. A tough and resilient woman in an era that bred some of history’s toughest and most resilient women, Alice probably would not be surprised.

Selected Sources:

Marjorie Anderson, “Alice Chaucer and Her Husbands,” in PMLA, March 1945.

Rowena E. Archer, “Chaucer , Alice, duchess of Suffolk (c.1404–1475),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2011.

Rowena E. Archer, “’How ladies . . . who live on their manors ought to manage their households and estates’: Women as Landholders and Administrators in the Later Middle Ages.” In Woman Is a Worthy Wight: Women in English Society c. 1200-1500, P. J. P. Goldberg, ed.

John A. A. Goodall, God’s House at Ewelme.

I. M. W. Harvey, Jack Cade’s Rebellion of 1450.

Karen K. Jambeck, “The Library of Alice Chaucer, Duchess of Suffolk: A Fifteenth-Century Owner of a ‘Boke of le Citee de Dames,’” in The Profane Arts (1998).

Susan Swain Madders, Rambles in an Old City, Comprising Antiquarian, Historical, Biographical, and Political Associations.

Carol M. Meale, “Reading Women’s Culture in Fifteenth-Century England: The Case of Alice Chaucer,” in Mediaevalitas: Reading the Middle Ages, Piero Boitani and Anna Torti, eds.

Nicholas Harris Nicolas, Testamenta Vetusta.

Colin Richmond, The Paston Family in the Fifteenth Century: The First Phase.

John Watts, Henry VI and the Politics of Kingship.

August 31, 2013

The Queen’s Sister: Cecily, Viscountess Welles

Stained glass at Canterbury Cathedral depicting Cecily and her sisters.

Cecily, the third daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville and the second to survive adolescence, was born at Westminster on 20 March 1469. It seems likely that one of her godmothers was her grandmother, Cecily, Duchess of York. Young Cecily was less than a month old when she became the topic of international gossip: Luchino Dallaghiexia, an ambassador in London, reported to the Duke of Milan, “The queen gave birth to a very handsome daughter, which rejoiced the king and all the nobles exceedingly, though they would have preferred a son.”

In October 1470, the toddler’s comfortable routine was shattered when Edward IV was forced by the rebellious Earl of Warwick to flee the country, causing his pregnant queen, her mother, and her daughters to take refuge in Westminster Abbey’s sanctuary. There, on 2 November, Elizabeth was delivered of her first royal son, Edward. The next spring, Edward IV recovered his throne, and Cecily resumed her life as a royal princess—albeit one now overshadowed by her brother.

Nonetheless, royal daughters had their own importance, and on 26 October 1474, Edward IV and King James III of Scotland agreed that Cecily would marry his heir. In 1482, however, when Anglo-Scottish relations soured, Edward IV offered Cecily to James’ rebellious younger brother, Alexander, Duke of Albany—although this would require Albany to free himself from his wife. In the end, however, Albany’s royal ambitions failed, as did both of Cecily’s prospective Scottish matches.

Meanwhile, on 15 January 1478, Cecily, a couple of months short of her ninth birthday, attended the wedding of her four-year-old brother Richard to the five-year-old Anne Mowbray. With her parents the king and queen, her grandmother Cecily, Duchess of York, her brother Prince Edward, and her older sisters, Elizabeth and Mary, Cecily stood under a canopy at St. Stephen’s Chapel at Westminster awaiting the young bride.

At some point in her father’s reign, Cecily was admitted to the Ladies’ Fraternity of the Order of the Garter. Her father ordered Garter liveries on 6 June 1482 for Cecily, her sisters Elizabeth and Mary, and the queen.

In company with her sister Elizabeth, Cecily inscribed the Estoire del Saint Graal (British Library Royal 14 E III). Both sisters signed themselves as “the king’s daughter.” The book was also signed by “E. Woodville,” possibly their uncle Edward Woodville or their mother Elizabeth Woodville before her marriage, and by a cousin’s wife, Alianore Haute. Elizabeth and Cecily’s signatures also appear in the Testament de Amyra Sultan Nichemedy, Empereur des Turcs; the title page is dated 12 September 1481.

Signature of Cecily on Royal 14 E III, f. 1

In 1482, Cecily’s older sister Mary, two years her senior, died. As Mary was the closest sister to Cecily’s age, it seems likely that her death must have been a particular blow to Cecily.

Cecily’s fortunes underwent another downward turn when her father died in April 1483. Amid the turmoil that followed, Elizabeth Woodville again fled to sanctuary, once more with her children in tow. This time Cecily did not emerge until March 1484, when the new king, Cecily’s uncle Richard III, pledged that he would provide for Elizabeth’s daughters—all of whom had been declared illegitimate based on the alleged invalidity of Edward IV’s marriage to their mother—and would arrange respectable marriages for them to “gentlemen born.”

In the event, Richard had time to arrange for only one such marriage—Cecily’s. Probably in early 1485, Cecily was married to Ralph, a younger brother of Thomas, Lord Scrope of Upsall. Born around 1465, twenty-year-old Ralph was four years older than sixteen-year-old Cecily. The marriage, however, was short-lived. Henry VII’s victory at Bosworth brought him the hand of Cecily’s sister, Elizabeth. Cecily’s marriage to Scrope was annulled, and before 1 January 1488, she had married John, Viscount Welles. John was a younger son of Lionel (or Leo), Lord Welles, who was slain at Towton in 1461. Through his mother, Margaret Beauchamp, duchess of Somerset, the widow of John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, John was a half-brother of Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond, mother to Henry VII. He had rebelled against Richard III in 1483 and had joined Henry Tudor in exile in Brittany. John’s manors were centered in Lincolnshire, where he sat on commissions of the peace.

As the queen’s oldest sister, Cecily was a prominent figure at court ceremonies. On 24 September 1486, she bore Prince Arthur to the baptismal font, assisted by her uncle Thomas Grey, Marquis of Dorset and by John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln. The ceremony complete, Cecily bore the prince to his proud parents.

The following year, on 24 November, Cecily bore her sister’s train as Elizabeth left her chamber to ride from the Tower to Westminster in preparation for her coronation. Cecily and her aunt Katherine, Duchess of Bedford and Buckingham, rode behind the queen in a chair “covered with rich cloth of gold, well and cleanly horsed.” Farther back, Cecily’s gentlewomen rode in their own suite. On the day of the coronation itself, Cecily again carried the queen’s train. She and her aunt Katherine sat on the left side of the queen’s table at the banquet that followed. Cecily was also present at the New Year’s ceremonies on 1 January 1488; at this time, she was identified as sister of the queen and as Viscountess Welles.

Elizabeth Woodville, Cecily’s mother, died on 8 June 1492. Cecily’s younger sisters, Anne, Katherine, and Bridget, attended the funeral, while Cecily did not. The reason for her absence is unknown; perhaps Cecily was attending Queen Elizabeth, who was confined due to her latest pregnancy. Cecily’s husband, however, did attend the ceremony.

Three years later, Cecily’s grandmother and namesake, Cecily, Duchess of York, died. In her will, dated 31 May 1495, the Duchess of York left Cecily two “portuouses,” which were breviaries or daily service books, one of which had silver and gilt clasps and was covered with purple velvet.

By 1492, Cecily and John Welles had two daughters, Elizabeth and Anne, whom John, preparing to go to France, mentioned in his will. Sadly, neither survived childhood. Elizabeth, who had been promised in marriage to the heir of George Stanley, Lord Strange, died in 1498, and Anne had also died before John Welles’ death on 9 February 1499. With these losses in such rapid succession, it was no wonder that Cecily was styled “not so fortunate as fair” by Sir Thomas More.

Cecily and John’s marriage has been portrayed in some novels as an unhappy one, but there seems to be no historical basis for this. John made Cecily an executor of his will, along with Sir Raynold Bray, a clear sign of his trust in her. He left his “dear beloved lady and wife” a life estate in all of his property and the residue of his goods. John asked that Cecily, the king and the queen, and Margaret Beaufort decide where he was to be buried, and left the making of his tomb to their discretion as well. He was buried in the Lady Chapel of Westminster Abbey.

On 14 September 1499, Cecily received a dispensation to have masses and other services celebrated in her chapel if she should happen to be staying in the diocese of Lincoln.

Cecily continued to play a role at court after her husband’s death. At the wedding of Prince Arthur to Katherine of Aragon on 14 November 1501, Cecily had the honor of bearing the bride’s train. The wedding was followed by days of festivities, during which the guests were treated to a series of elaborate pageants. Following the third pageant, Prince Arthur and Cecily led off the dancing by performing two stately basse-dances, followed by Katherine of Aragon and one of her ladies, then by the Duke of York (the future Henry VIII) and his sister Margaret.

But Cecily’s days at court were drawing to a close. Sometime in 1502, Cecily married Thomas Kyme of Friskney, a Lincolnshire esquire, without royal license. This Thomas Kyme was the son of John Kyme, and appears to have had at least one son, Thomas, from a previous marriage. Cecily’s marriage to a man far below her rank infuriated Henry VII and resulted in the seizure of Cecily’s estates. Fortunately, Cecily had a powerful friend and advocate: the king’s mother.

Margaret Beaufort and Cecily had long been on friendly terms. Henry Parker, Lord Morley, recalled that on New Year’s Day 1496, when he was a fifteen-year-old employed in Margaret’s household, he saw Cecily sitting by Margaret’s side under the cloth of estate. Now Margaret intervened on Cecily’s behalf. She allowed Cecily and her husband to stay at her house at Collyweston while she brokered a settlement involving the king, Cecily, and the coheirs to the Welles estates. By 1503, Cecily agreed to surrender certain manors in Lincolnshire to the king; she was to hold the other manors for life, after which they would revert to the crown for ten years before being distributed to the Welles heirs. Her husband was allowed to retain the revenues he had received from the Welles estates. Although it has been suggested that the validity of Cecily’s unlicensed marriage was never recognized, the parliamentary petition for approval of this arrangement refers to Cecily as Kyme’s wife.

While all this wrangling over Cecily’s estates was occurring, Cecily’s sister Queen Elizabeth died on 11 February 1503, of the aftereffects of pregnancy. If she had approached the king on Cecily’s behalf, it is not recorded. Cecily had been in Elizabeth’s company at some point before 18 May 1502, when she was repaid the 73 shillings and 4 pence (3l, 13s, 4d) she had lent the queen. Cecily does not appear to have attended her sister’s funeral, where her younger sister Katherine served as chief mourner. Presumably she was still out of favor. Nonetheless, she was remembered by the young Thomas More in his verses commemorating the queen’s death:

Lady Cecily, Anne, and Katherine

Farewell my well beloved sisters three

O lady Bridget other sister mine

Lo here the end of worldly vanity

A story has arisen that Cecily’s husband was a native of the Isle of Wight and that the couple lived there; however, Rosemary Horrox finds this tradition, and an accompanying one that gives Kyme and Cecily children, to be unfounded. (Cecily’s inquisition post mortem for Essex mentions no children.) Probably Cecily and her husband spent their time on his estates and on the estates Cecily had recovered from the king, which included Gaynes Park, Hemnalls, and Madells in Essex. She was in Herefordshire before 11 December 1506, when Henry VII paid a messenger for riding to her. Cecily and her husband also continued to spend time with Margaret Beaufort, who in 1506 set aside a chamber at Croyden for Cecily’s use. During their visits to Margaret, Cecily, her husband, and their servants were charged for their board, as were other guests. Margaret gave a “fine image” to Cecily in 1503, and owned a “printed legend” purchased from Cecily.

At the age of thirty-eight, Cecily died at Hatfield in Hertfordshire on 24 August 1507; she had been staying in that house, then a possession of the Bishop of Ely, for three weeks. (Horrox notes that the tradition that Cecily was buried at Quarr Abbey on Isle of Wight is disproved by Margaret’s accounts.) Cecily was buried at a place identified only as “the friars,” with Margaret Beaufort paying most of her funeral expenses.

Thomas Kyme appears to have survived his wife; a Thomas Kyme of Friskney figures in litigation, both as a plaintiff and a defendant, in the first few decades of the 1500’s. It may have one of his descendants who married the ill-fated Anne Askew.

Cecily is the heroine of a trilogy of novels by Sandra Wilson: Less Fortunate than Fair, The Queen’s Sister, and The Lady Cicely.

Sources:

Marie Axton and James P. Carley, eds., “Triumphs of English”: Henry Parker, Lord Morley, Translator to the Tudor Court.

Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, Henry VII, vol. 3.

Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts in the Archives and Collections of Milan – 1385-1618.

James P. Carley, “Parker, Henry, tenth Baron Morley (1480/81–1556),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

Emma Cavell, ed., The Heralds’ Memoir 1486-1490: Court Ceremony, Royal Progress and Rebellion.

James L. Gillespie, “Ladies of the Fraternity of Saint George and of the Society of the Garter,” in Albion (Autumn 1985).

Mary Anne Everett Greene, Lives of the Princesses of England.

Michael Hicks, “Welles, Leo , sixth Baron Welles (c.1406–1461),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

Rosemary Horrox, ‘Cecily, Viscountess Welles (1469–1507)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

Rosemary Horrox, Richard III: A Study in Service.

Gordon Kipling, ed., The Receyt of the Ladie Kateryne.

Michael Jones and Malcolm Underwood, The King’s Mother: Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby.

St Thomas More, The History of King Richard III and Selections from the English and Latin Poems (Richard S. Sylvester, ed.).

Arlene Naylor Okerland, Elizabeth of York.

Parliament Rolls of Medieval England.

Vivienne Rock, ‘Shadow Royals? The Political Use of the Extended Family of Lady Margaret Beaufort’ in Richard Eales and Shaun Tyas, eds., Family and Dynasty in Late Medieval England.

Alison J. Spedding, “‘At the King’s Pleasure’: The Testament of Cecily Neville,” in Midland History (Autumn 2010).

Surtees Society, North Country Wills.

Anne Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs, The Royal Funerals of the House of York at Windsor.

Malcolm Underwood, ‘Politics and Piety in the Household of Lady Margaret Beaufort, in Journal of Ecclesiastical History (January 1987).

August 24, 2013

Search Terms!

It’s time for some search terms!

did elizabeth woodville have a son with edward

No. Those princes in the Tower that people have been arguing about for centuries are purely theoretical.

night justiciar cat games

So that’s what they’re meowing about at 3 a. m.!

who did edward 4 th daughter elizabeth marry

Some Welsh dude, I’m told.

harry stafford duck of buckingham

Sometimes nobility just isn’t what it’s quacked up to be.

was edward of westminster a monster?

I don’t know, but primary sources make it clear that he wasn’t a duck.

did henry iii rape anne boleyn

No. That was Simon de Montfort, silly.

king richard 111 aneurin barnard where should richard be buried?

Shouldn’t someone consult the actress who played Anne?

elizabeth woodville lesbian

And you thought Jane Shore was visiting sanctuary just to plot.

August 15, 2013

Arms and the Man: Was Edmund Tudor Illegitimate?

Recently, historian John Ashdown-Hill published a book called Royal Marriage Secrets, in which he purports to uncover evidence that Edmund Tudor, father of Henry VII, was not the son of Owen Tudor but of Edmund Beaufort—evidence, in short, that would entail renaming an entire dynasty.

The speculation does have some basis in fact. Following the death of Henry V, Catherine of Valois, a widow of only twenty-one, was said to have difficulty “curb[ing] fully her carnal passions,” and a contemporary rumor had it that Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset (d. 1455) sought to marry her. The result was this statute, which refers to queens generally but is generally regarded by historians as being aimed at Catherine:

Item, it is ordered and established by the authority of this parliament for the preservation of the honour of the most noble estate of queens of England that no man of whatever estate or condition make contract of betrothal or matrimony to marry himself to the queen of England without the special licence and assent of the king, when the latter is of the age of discretion, and he who acts to the contrary and is duly convicted will forfeit for his whole life all his lands and tenements, even those which are or which will be in his own hands as well as those which are or which will be in the hands of others to his use, and also all his goods and chattels in whosoever’s hands they are, considering that by the disparagement of the queen the estate and honour of the king will be most greatly damaged, and it will give the greatest comfort and example to other ladies of rank who are of the blood royal that they might not be so lightly disparaged.

Assuming that he actually did have ambitions to marry Catherine, Edmund Beaufort heeded this warning; Owen Tudor, a mere squire, did not. At some point, he and Catherine of Valois secretly married and had a family of children together.

Ashdown-Hill, however, speculates that two of these children were fathered not by Owen, but by Edmund Beaufort out of wedlock. Unlike other historians who have indulged in such speculation in the past, he claims to have found concrete evidence that Edmund Tudor, and his brother Jasper, were Edmund Beaufort’s illegitimate offspring: their coats of arms. “These coats of arms, which owed nothing whatever to the arms of Owen Tudor, were clearly derived from the arms of Edmund Beaufort. The blue and gold bordures of Edmund and Jasper Tudor were simply versions of the blue and white bordure of Edmund Beaufort. . . . The whole purpose of medieval heraldry was to show to the world who one was. And the coats of arms of Edmund and Jasper Tudor proclaimed, as clearly as they could, that these two ‘Tudor’ sons of the queen mother were of English royal blood, while their bordures suggest descent from Edmund Beaufort. The only possible explanation seems to be that Beaufort was their real father.”

As further “proof,” Ashdown-Hill writes that a century later, Henry VIII rescued only two bodies from the dissolution: that of his sister Mary and his grandfather Edmund Tudor. Noting that Henry failed to retrieve his great-grandfather Owen’s body, Ashdown-Hill asks, “Could it have been that Henry VIII knew more about his true paternal ancestry than later historians?”

This, however, is awfully slender evidence on which to impugn Queen Catherine’s virtue—especially when one considers all of the evidence that Ashdown-Hill overlooks. First, as my friend Karen Clark pointed out on a Facebook discussion of this question, there is the strong resemblance between the Tudor brothers’ arms and that of their half-brother, Henry VI—suggesting that the coats of arms were designed to indicate not ancestry from Edmund Beaufort, but their kinship to Henry VI.

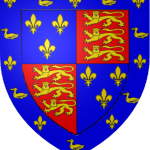

Henry VI’s arms

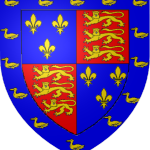

Edmund Tudor’s arms

Jasper Tudor’s arms

Beaufort arms

Indeed, the Act of Parliament creating Edmund and Jasper earls, unmentioned by Ashdown-Hill, stresses the brothers’ relationship to the king (and their legitimacy):