Harry S. Dent Jr.'s Blog, page 74

September 14, 2017

Can Big Data Mean Big Profits?

You don’t need me to tell you that the internet is a dizzyingly vast world that’s only getting bigger and more complex.

You don’t need me to tell you that the internet is a dizzyingly vast world that’s only getting bigger and more complex.

It amazes me how quickly we’ve become accustomed to the interconnectivity of our online life. Those discounted shoes you checked out while on a break at work? An ad for those very same shoes appears in your Facebook feed and in your Google search results and whatever news website you frequent most.

Our online footprint – a veritable mountain of big data – follows us wherever we go, and companies are scrambling to find ways to monetize it.

You can hardly imagine how much money there is to be made if someone were able to connect all the dots and map all the footprints in one place at the push of a button.

Companies that rely on any sort of marketing (which is basically every company out there) would fall over themselves and pay any price for that sort of tool.

Well, the company we found in this month’s issue of Hidden Profits is uniquely positioned to do just that.

But let me back up a bit first.

You’ve probably heard of Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire former mayor of New York City.

What you may not know is how he made his fortune.

Finding Profits in the Tech Market

Investment and business research, along with journalism and the publishing world writ large, used to be firmly grounded in the world of paper. Computers began helping in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, but it wasn’t until the 21st century that the Internet Age accelerated the marginalization of the printed word and the hegemony of the pixelated word.

For the financial world in particular, the first enduring revolution came with the “Bloomberg Terminal,” a computer software system that keeps track of, in a word, everything.

With an annual subscription Wall Street wizards and wannabes could get all the information they needed through one powerful machine housed on their desks, obviating the need for legions of interns to scour the web and printed sources of data.

“Everything,” in this context, means precisely that: from headlines in India to what the Venezuelan bolivar trades at in South Africa to every single media mention of a small miner in a remote corner of Australia that’s not even public yet.

Bloomberg met a huge need so well that it grew subscriptions at a dizzying rate. Everyone in the financial world has a Bloomberg terminal or is close to one. There are more than 300,000 subscribers worldwide, and they pay about 20 grand per year. In 2011, the Bloomberg terminal made up more than 85% of the company’s revenue.

As I mentioned earlier, if there were some sort of Bloomberg machine equivalent that could be used to track and analyze (and, in effect, monetize) online traffic, well, that’d be a big deal.

And I’m pretty sure I found it.

The guy at the head of this company built the worldwide software mega-giant Oracle’s cloud platform from nothing into a multi-billion-dollar business. It’s hard to imagine anyone better at the helm, someone who knows “long lead times” and the software subscription game.

Its current market base is already $3 billion, but it has its sights set squarely on the $32 billion marketing software market and the whopping $195 billion digital marketing market. Those markets are 10 to 65 times greater than its current market.

It’s easy to see that making the slightest dent in those markets would balloon Cision’s valuation. Only moderate success is required to provide multi-bagger returns.

This is a story that’s happening right now, all around us, except now there’s a way to profit from it. Take a look.

Good investing,

John Del Vecchio

Editor, Hidden Profits

P.S. We’re now less than a month away from the Irrational Economic Summit Oct. 12-14 in Nashville, where I’ll be speaking on investing for income and a lot more. Be sure to get your ticket if you haven’t already. I hope to see you there!

The post Can Big Data Mean Big Profits? appeared first on Economy and Markets.

“Reports of My Death Have NOT Been Greatly Exaggerated!” Regards, Retail

The retail apocalypse coming to a mall near you

The retail apocalypse coming to a mall near youIs this retail apocalypse you’ve been hearing so much about a reality?

Is this really the end for the American shopping mall?

Yes! And it’s going to get worse, but I want you to see why it was totally predictable.

In fact, just like we forecast that Harley Davidson would suffer, so too did we forecast that retail stores would take a hit with the predictability of spending waves!

Yes, the retail, brick-and-mortar, industry is suffering because there are too many stores, online shopping is growing exponentially and shoppers are “moving toward experience…”

And yes, internet retailers like Amazon are disrupting shopping malls and big-box stores.

It’s competitive capitalism, and it’s the reason we live in a wealthy country today.

But there’s something so much bigger than all of these things going on, and everyone seems to be missing.

All the retail store closings and bankruptcies were baked into the cake because of a massive demographic trend that peaked in late 2007.

As enormous as e-commerce has become… and as quickly as it continues to grow, it’s nothing compared to the role demographics has played in dictating the fate of the retail economy.

With clothing retail stores like Macy’s and JCPenny sucking more and more wind, how much longer will they be able to tread water? And is there any relief on the horizon?

In our latest infographic, The End of Retail as We Know it, we dive deep into the decline of the retail industry and reveal how a culprit even larger than Amazon, has buried retail stores everywhere and why you’ll see even more consolidation in the years ahead.

The post “Reports of My Death Have NOT Been Greatly Exaggerated!” Regards, Retail appeared first on Economy and Markets.

September 13, 2017

The Future of the U.S. (And the World)

Predictability.

Predictability.

People.

Those are the two keystones of my research and forecasting successes: cycles and demographics.

It can all be traced back to the day I was studying several charts that I’d laid out on my desk. I’d been looking at the Dow Jones Industrial Average adjusted for inflation when I glanced up and spotted the Baby Boomer’s birth wave.

I was confused for a second. They looked identical.

So, I laid the one page on top of the other, moved the demographic chart to the right by about 45 years, and they were a match! I immediately knew why, as I had already studied Baby Boom demographics for several years and knew that they peaked in spending between age 45 and 49. I later found that the more exact peak and correlation was 46 years.

Definitely a Eureka! moment. I nearly fell off my chair.

That discovery has since become known as my Spending Wave! It’s allowed me to make eerily accurate long-term forecasts (although, by itself, it’s not a perfect tool – there is no such thing).

It was what enabled me to see that Japan was heading for trouble in the late 1980s when the rest of the world thought they were going to overtake the U.S. It was the reason I knew we’d have a roaring 2000s when everyone else was preaching doom and gloom after the tech wreck. And it’s what tells me that we’re headed toward trouble (and I’m not just talking about the looming market crash)…

The U.S. generational spending wave began to slow down after 2007, right on that 46-year lag. It continues this downward trend into around 2023 or so, with the worst coming by 2020. After that, there’s a longer-term rally into 2036 or 2037 for the first wave of the Millennials born into 1990, followed by a 7-year birth decline and hiatus, and then another rally into around 2056 or so, with the second wave of Millennials born into 2007…

But, here’s the thing: Stocks and the economy likely won’t exceed the highs we’re enjoying today – at least not adjusted for inflation. And there are several reasons for that.

Firstly, while the Millennial generation is larger in numbers, it’s spread thinner over time than the Baby Boom generation is. This gives the latter more economic punch than the former. It’s like the difference between gentle rolling waves and a tsunami.

Secondly, we’re plateauing as a nation. After 2056 our population will likely decline slowly for a long time. And this projection is optimistic. What lies ahead for Germany and Japan is much worse! I’m talking catastrophic and fatal, respectively.

Here’s what our future looks like for the rest of this century… a 93-year forecast. How many economists do you know can even remotely do that?

This chart already includes, on a 47- to 49-year lag, the next Millennial generation into around 2065 (using historical and present births and immigration data). This new generation looks to peak in spending a few years later than the Baby Boomers, which peaked at 46 (the Bob Hope generation peaked at age 44).

This chart already includes, on a 47- to 49-year lag, the next Millennial generation into around 2065 (using historical and present births and immigration data). This new generation looks to peak in spending a few years later than the Baby Boomers, which peaked at 46 (the Bob Hope generation peaked at age 44).

The present Spending Wave lag for Generation X, or the downward birth wave following the Baby Boom is 47.

Peak spending for the first wave of Millennials is 48. For the second wave up, it’s 49, and it’s 50 for the longer wave down, which is projected to bottom in births into 2023 due to worsening economic conditions. That creates the next great depression into around 2073, and possibly a bit later.

We update this chart regularly to account for actual births and immigration and for the economic outlook for future trends in both!

Hence, we can project further out than 47 years-plus with reasonable accuracy…

I predicted many years ago that the birth rates would peak near 2007, when the economy was at its best thanks to Baby Boomer spending. People tend to have fewer kids when the economy looks bad or questionable, and vice versa. For example, births and immigration declined sharply into 1933 on a nine-month lag (for pregnancy) after the worst stock downturn in U.S. history.

This trend of slowing births began again in 2008, after the Great Recession began.

I also predicted that immigration would peak and decline after 2007, just like it did into the 1930s dismal economy. And it is! Immigration from Mexico in particular actually reversed for a while.

David Okenquist, my research analyst, and I have done detailed analyses of how births and immigration could decline in the greater downturn we’ll see ahead. I’m beginning to think we may be underestimating the impacts we’ll see in the next several years!

Government agencies tend to project demographic changes in a straight line, using the most optimistic assumptions rather than recognizing fundamental shifts in birth rates, immigration, or urbanization. There is no straight line. Only cycles… peaks and valleys.

Yet the government is forecasting 60 million more births and immigrants between now and 2060 that what we believe will actually arrive. That’s a huge difference! Our population growth will only be about 0.27% a year.

Given lower forecasts for births and immigration into the downturn into 2023 (and rising again after that), and the fact that increasingly urban and affluent households tend to have fewer children because of the expensive involved in raising and educating them, we’ve extended the Spending Wave for the U.S. past 2065 into 2107!

The resultant picture shows, as I said earlier, a double boom from 2023/24 into 2036/37, then a slowdown from 2037 into 2045, then a second boom from 2046 into 2056.

After that, U.S. demographics decline into around 2073, especially after the late 2060s. That should be the next great depression, after India – what I believe will turn out to be the next China – peaks demographically and in its urbanization.

So…

Prepare now for the impacts of the Spending Wave on your financial, investment, and business decisions. Then teach your kids and grandkids this stuff, so they’re not caught unaware later.

And join us at the Irrational Economic Summit in October. We’ll be sharing details of several strategies you can implement now, AND share with your kids later. We’re thinking outside the box this year – way outside the box – and looking to space, the seas and blockchain technologies for opportunities.

Harry

Follow me on Twitter @harrydentjr

The post The Future of the U.S. (And the World) appeared first on Economy and Markets.

September 12, 2017

How Investors are Falling Short on Their Returns

Hear of the investing phenomenon of home-country bias? If you’re a regular reader, you definitely have because it’s something I’ve talked to you about often in recent months, including a two-part series, you can see here and here.

Hear of the investing phenomenon of home-country bias? If you’re a regular reader, you definitely have because it’s something I’ve talked to you about often in recent months, including a two-part series, you can see here and here.

I do this because it’s pervasive across time and geography… and it can be very damaging to your investment portfolio if ignored.

It may make investors feel all warm and fuzzy inside, but it generally tricks us into accepting lower returns and higher volatility from domestically-tilted portfolios.

In the U.S., this is particularly prevalent. Americans prefer investing in U.S. stocks because, psychologically, it feels like the right thing to do.

But it’s not!

And it’s hurting your portfolio.

In the following infographic, How Investors are Falling Short on Their Returns, we look at several different reasons why you should avoid falling prey to the phenomenon of home-biased investing and what could happen if you take advantage of opportunities abroad…

The post How Investors are Falling Short on Their Returns appeared first on Economy and Markets.

September 11, 2017

I’ve Seen This Movie Before: Deceit in the Financial Food Chain

I recently watched The Big Short, the 2015 movie recounting the housing crisis. I avoided the movie, and the book of the same name, for years. But I saw the title on Netflix and thought, “Now’s the time.”

I recently watched The Big Short, the 2015 movie recounting the housing crisis. I avoided the movie, and the book of the same name, for years. But I saw the title on Netflix and thought, “Now’s the time.”

I didn’t sidestep it for lack of interest. Just the opposite. As a former bond trader I have a keen interest in the debt markets.

I followed the crisis’ every twist and turn, starting in the summer of 2007 when a quiet little corner of the bond market – municipal bond floating-rate note auctions – blew up. I found the steps leading to the crisis, and the events in the aftermath, appalling.

As I watched the movie, the sense of dread and disappointment I felt 10 years ago rushed back. So did the anger.

“Not my fault.”

That’s what everyone involved in the financial food chain said.

It wasn’t the fault of mortgage brokers who peddled so-called NINJA loans to people who had no clue how mortgages worked. These loans required no documentation. They were “No Income, No Job Applications,” hence the acronym.

Mortgage brokers made truckloads of money without explaining the risks while homebuyers took on adjustable-rate mortgages on inflated properties. Sure, the risks were buried in the paperwork somewhere… in legal language required by the federal government. None of these people went to jail.

It wasn’t the fault of investment banks that took the bogus mortgages, bundled them with others, and claimed through the magic of finance that the entire package was miraculously the highest-quality bond available.

This alchemy allowed the investment banks to charge high interest rates on the mortgages, and sell the repackaged loans at lower interest rates to pension funds, individuals, insurance companies, and anyone else who needed yield. None of these people (except for one, convicted of fraudulently hiding trading losses) went to jail.

It wasn’t the fault of rating agencies. They knew the bonds were junk, but gave them AAA ratings anyway. When sued for fraud, the agencies claimed their first amendment right to say whatever they want. They said their ratings were just their “opinion.”

We know why they slapped AAA on everything. If they didn’t, the investment banks would’ve taken their business elsewhere, robbing the rating agencies of revenue. None of them went to jail.

And then we bailed out the world.

The Financial Bailouts

The Bush administration lent money to the automakers, who had made deals with unions (both pay and pensions) that they couldn’t support. Then the automakers declared bankruptcy.

The Obama administration gave them the ultimate bailout gift, allowing them to leave behind “bad” assets in an old company and move “good” assets to a new company. The two-step crushed investors, leaving them with pennies on the dollar, if anything, while guaranteeing union retirees 100% of their gold-plated pensions.

White-collar retirees had their pensions shifted to the government-operated Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp, which dramatically reduced their monthly incomes.

A lovely side benefit of the deal was that GM could carry forward its losses from the “old” company to the “new,” and use that ability to offset profits for years, saving the company billions in taxes.

Homebuilders, who’d printed cash during the housing boom, were given a special tax deal too. The government allowed them to match losses during the crisis against profits from previous years on a much longer lookback than typically permitted.

This gave homebuilders hundreds of millions and, sometimes, billions of dollars in tax refunds during the down years. Interestingly, they didn’t use any of it to refund homeowners who bought properties at wildly inflated levels.

And then, there were the bankers. Those lovely individuals who were simply “in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Sure.

The Federal Reserve, at the behest of and then in conjunction with Treasury Secretaries Hank Paulson and Tim Geithner, provided a financial backstop for everyone from AIG to Bank of America. Many of these firms owned derivative investments, which gained or lost when valuations on other transactions changed.

No one knew exactly what they owned because assets of all kinds tanked, but many had transactions with AIG. Government officials asked these banksters to consider taking less than 100% payback to unwind the transactions. They said “No.”

We, as the guarantors of AIG, paid 100 cents on the dollar, even though none of the bankers could have refused whatever we had chosen to pay. None of these people went to jail.

But “no jail” and “no consequence” aren’t the same thing.

The government clipped many of these companies for big money, claiming billions of dollars in restitution.

Right.

The funds weren’t sucked out of the personal bank accounts of those that made the decisions (and bonuses) in the go-go years. The money came out of corporate coffers, which means from investors.

Which brings me back to why I avoided The Big Short for two years.

Trust and the Financial Food Chain

It reminds me how many people in the food chain do not care about any outcome beyond their pocketbook. Considerations like “good for the clients,” or “good for the economy,” or even simply “morally defensible” don’t exist.

They have two goals: Make the most money possible and stay out of jail. They did their best on the first one, and we gave them a pass on the second.

I don’t trust what I hear from any of them. The mortgage brokers. The investment banks. The rating agencies. The bankers.

I don’t believe that our debt woes are completely behind us.

I don’t think demanding companies produce more goods in the U.S. will solve our long-term structural employment issues.

I don’t think simply putting my savings in the hands of Corporate America and hoping for the best is the smartest investment strategy.

And I don’t think government officials worry about my financial well-being.

Research, like we provide, is the best ally. Active management is both the best offense and best defense.

We have to be responsible for our own financial futures, keeping in mind Ronald Reagan’s famous words, “Trust, but verify.” For most of us, there won’t be anyone standing at the end of our financial journeys to unwind missteps and bad decisions.

There are only so many people that get to claim, “It’s not my fault,” and have the government pick up the tab. I’m not one of them, and I bet you aren’t, either.

Rodney

Follow me on Twitter @RJHSDent

The post I’ve Seen This Movie Before: Deceit in the Financial Food Chain appeared first on Economy and Markets.

September 7, 2017

The Three Rules of Angel Investing: From Someone Who’s Tried

Salesmen rarely make good managers or business owners. But that doesn’t stop them from trying.

Salesmen rarely make good managers or business owners. But that doesn’t stop them from trying.

It used to be a hallmark of American business that successful salesmen were promoted. The logic is obvious. Whatever makes Joe or Amy great at selling the company wares should be emulated by others, thereby making the company more successful.

But selling and managing require very different skills, much like playing a sport and coaching are different.

Sometimes good salesmen, people with great interpersonal skills who grasp what’s important to other parties in conversation, can successfully transition to running a business. But more often than not, they lack the attention to detail and ability to switch between focusing on the big picture and mastering the nuances of daily operations to succeed.

In the end, everyone is frustrated, and the company hasn’t prospered as expected.

The same thing happens in our personal lives. We achieve success in one area, and assume that it’ll happen in other areas. For too many people, myself included, the result is frustration. In my case, I get the added bonus of losing money.

I started my Wall Street career trading bonds. I know the interest rate market inside and out. I can discuss Liquid Yield Option Notes (LYONs), inverse floaters, and repurchase option agreements, and I know the ins and outs of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) as well as derivatives on debt. I understood the financial crisis at a level that made me sick.

I’ve also spent many years investing in equities and options, and I use a proven strategy to run my Triple Play service. All of this makes me well educated in the world of finance.

None of this makes me an astute investor of early-stage businesses. But that doesn’t stop me from trying.

My History in Angel Investing

The siren song of 1,000% gains lures me in. And I’m swayed by the idea of bypassing all the noise on Wall Street. So from time to time, I open my checkbook and break one of my investing rules. I get involved in something that’s not my expertise. The outcome is predictable.

In 2008 I had the chance to invest in an ethanol plant. I passed. I saw ethanol on the rise, but our economic forecast called for slow GDP growth, and as a nation we were making strides in better fuel efficiency. Stepping aside was a good move.

I also got the chance to invest in old, land-based oil wells. Not shale fracking, but swabbing old-style wells. This would have been a disaster in the face of falling oil prices.

But a new memory chip company hooked me. This firm makes large chips that are used in many renewable fuel applications, and it has few competitors. The story was solid, as were the books. The management team had great experience and past success. The goal was to grow the business for 24 to 36 months, then either IPO or sell to a large competitor.

I’m still waiting.

The latest plan is to take the company public. In Hong Kong. In 2019. The company still makes a great product, but for whatever reason, it hasn’t attracted a buyer at the right valuation.

I’ve also put money into a biotech company. It’s not exactly angel investing since the shares trade publicly, but they trade on the bulletin board at less than $1. I heard about the company from a financial advisor I like and trust. I also met several investors over a meal. The company was expected to announce a breakthrough within the year.

That was three years ago. I still own the shares.

As with the chip company, this firm still has tremendous promise. I’m not counting it out. But neither investment has performed as expected. I haven’t earned the returns I anticipated, and, in the case of the chip company, I don’t have liquidity.

The point of reviewing these examples is to highlight what it takes to be a great angel investor. You have to do one of two things. Stick to something you know exceptionally well and resist the urge to be led astray by success in another field, or invest in a wide array of opportunities to increase your likelihood of success.

There is a third option. Follow someone who’s proven to be successful several times over in picking great, early-stage companies. We’ll have one, Howard Lindzon, at our Irrational Economic Summit in October. There’s nothing wrong with the “me, too” style of investing, especially if it gives you the results you want.

Those words echo in my head I as reflect on my latest early-stage investment. Earlier this year I put a small amount of money into a new microbrewery (yes, I know, the market is saturated). Their angle is that they partner with musical acts, perfecting brews that match the taste of the band.

If you’ve had Hootie’s Homegrown Ale, Rebelution’s Feeling Alright IPA, or 311 Amber Ale, you’ve tasted our wares. They also have a small, 175-person performance venue above the brewery in historic Ybor City in Tampa, Florida.

I have no idea if it will make any money, but at least I can kick back with a cold one and listen to some good music!

Rodney

Follow me on Twitter @RJHSDent

The post The Three Rules of Angel Investing: From Someone Who’s Tried appeared first on Economy and Markets.

Is the Federal Reserve Doing Its Job?

Today let’s talk about the Federal Reserve’s “dual mandate” from Congress. It’s a phrase that gets thrown around a lot, so it’s worth unpacking.

Today let’s talk about the Federal Reserve’s “dual mandate” from Congress. It’s a phrase that gets thrown around a lot, so it’s worth unpacking.

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 established the central bank as we know it today, and, later, Congress also charged (mandated, if you will) the institution to promote maximum employment as well as stable prices – thus, a dual mandate.

This has proven to be a difficult, if not impossible, task.

In 2012, for the first time in its history, the Fed established an inflation target. Even after trillions of dollars in quantitative easing and years of “ZIRP” (zero interest–rate policy) that target, 2%, is yet to be met.

The Fed seems perfectly happy with itself because the unemployment rate has fallen to historically low levels, now reportedly at 4.4%. Job creation seems to be moving at a healthy pace, but wages aren’t rising.

In fact, last Friday’s August jobs data only showed a 0.1% month-over-month increase in hourly earnings and meager 2.5% year-over-year gain.

There’s no getting around it: Wage growth was a disappointment once again.

And so the Fed seems confused (again).

The central bank links wages to lower-than-expected inflation. Over the last eight years, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the U.S. economy has added about 12.2 million jobs. But a big assumption the BLS makes is the birth/death adjustment, which may have overstated job creation by nearly 50% since 2009.

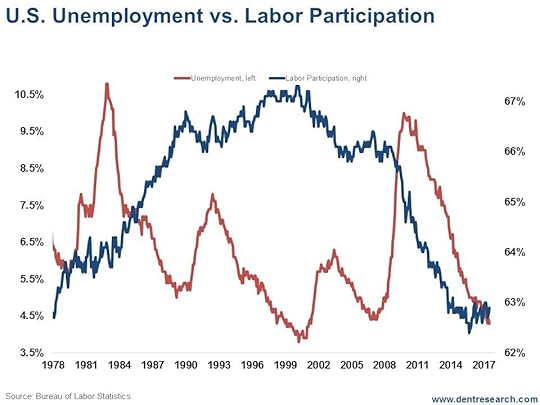

The BLS model assumes an increase in new entrepreneurship and associated jobs. The BLS also fails to account for part-time jobs and contract jobs that replaced full-time jobs. Meanwhile, the labor force participation rate has been falling for the last 17 years and hasn’t been this low since the Carter administration. This statistic tells us how many people over the age of 16 have jobs.

Take a look at the chart below…

I’m really not sure why the Fed seems so confused.

It’s pretty obvious that if the number of people working has decreased and the population has increased, the employment picture really isn’t all that good-looking. Perhaps the ways the unemployment rate and number of jobs created are calculated are wrong.

And perhaps if the jobs picture is as weak as the participation rate says it is, it’s no wonder wages aren’t rising like they should.

And that might explain why inflation is stubbornly low.

What’s there to be confused about?

Is the Fed really focused on jobs and inflation, as per its dual mandate? Have the trillions of dollars the Fed spent on quantitative easing and bailing out banks generated jobs, fueled economic growth, and inflated prices?

Or have its policies just propped up financial assets and bank profits?

I’ll let you come to your own conclusion.

Setting aside our central bankers’ ineptitude, the Fed’s policies do move markets, and that’s where opportunities to make profits happen.

And if you are interested in hearing more about the Fed and how you can profit from overreactions in the Treasury bond market, I’ll be speaking at our annual Irrational Economic Summit in October. I hope to see you there!

Good investing,

Lance Gaitan

Editor, Treasury Profits Accelerator

The post Is the Federal Reserve Doing Its Job? appeared first on Economy and Markets.

September 6, 2017

3 Ways to Survive the Next Stock Crash

Misconceptions about investment systems abound. It’s an esoteric field, so I’m not surprised. Most on the outside tend to think of systems as mysterious, robot-driven, “black box” investment things. The reality isn’t that mysterious or complicated.

Misconceptions about investment systems abound. It’s an esoteric field, so I’m not surprised. Most on the outside tend to think of systems as mysterious, robot-driven, “black box” investment things. The reality isn’t that mysterious or complicated.

A systematic investment strategy starts with an idea… which turns into a hypothesis… which is then proven or disproven.

The idea can be as simple as: “I think cheap stocks beat expensive stocks in the long run.” That value investing hypothesis has been studied and tested for decades now and has proved to be worthwhile.

Of course, a keen observation about the markets can prove invaluable, but it’s no systematic strategy. Take Kyle Bass, founder of Hayman Capital in Dallas. In 2006, he created a hedge fund to exploit a single hypothesis: that the U.S. subprime mortgage market would implode.

That market did implode. And Mr. Bass made a ton of money. But he’ll need to come up with a new great idea for his next fund.

Unless you’re Kyle Bass in the making, or he’s your mentor, you’d do better to adopt a systematic investment strategy that exploits events that repeat with a good deal of regularity.

Today I’ll help you with that…

Cliff Asness of AQR Capital Management (a quantitative/systematic hedge fund) explained why a strategic investment system is important. During an interview with Steve Forbes, he said (paraphrased):

With systems, you’re leveraging an idea… that cheap always beats expensive, or that low-volatility always beats high-volatility. And you’re applying that idea across hundreds of symbols… so that, in the long run, you’re exploiting the mathematical edge that’s contained in your idea.

THAT’S the essence of a system.

That’s what I aim to do with Cycle 9 Alert and 10X Profits.

The idea behind Cycle 9 Alert is simple: Everything cycles through periods of underperformance and outperformance.

That idea applies to sectors within the stock market… to individual stocks within sectors… and also to asset classes outside of equity markets, like commodities, currencies, and bonds.

That’s important to pay attention to. I don’t just focus on stocks. If I did, it would be a surefire way to miss out on great opportunities elsewhere.

I also don’t focus solely on U.S. markets. If I did, we’d have missed the outperformance of foreign markets this year and not been able to bank the 129%, 114%, and 149% we grabbed betting on Canada, Mexico, and China respectively.

The stock market’s not the be-all and end-all. Sure, it’s had a great run since early 2009. But the bull market won’t last forever. In fact, now more than ever, the threat looks to be growing.

At best, the risk-adjusted returns the U.S. equity markets could produce over the next five years are likely to pale in comparison to the last five years. At worst, any number of global risks could trigger a repeat of the 2008 stock market crash.

Either way, looking for Cycle 9-style opportunities outside the stock market and outside the U.S. is a must. It should be a requirement in any investment strategy you decide to go with.

The good news is: A careful study of historical stock market crashes reveals which asset classes are safe haven plays in times of crisis.

Here’s a sampling of three, non-equity investments that did quite well to cushion the blow of a plummeting stock market in 2008. These are the three ways you can survive the next crash.

First, a currency…

1. Japanese Yen (CurrencyShares Japanese Yen ETF: FXY)

Between September and December 2008, FXY gained 16%, while the S&P 500 (SPY) lost 29%.

That’s because the yen, along with the U.S. dollar, is a safe-haven currency that goes up when everything else in the investment world is going down.

Next, a bond fund…

2. 2-Year Treasury Bonds (via ETF: SHY)

My Cycle 9 system generated four buy signals on the Barclays Low Duration Treasury ETF (NYSE: SHY) between July 2007 and January 2009. Each one was profitable… because, like with the yen, the dollar is a safe haven currency, so investors tend to clamor for U.S. Treasury bonds when it seems as if the world is ending.

Finally, a basket of commodities…

3. PowerShares DB Commodity Index (NYSE: DBC)

Commodities sold off alongside equities during the second half of 2008. But that doesn’t mean there weren’t any gains to be had buying commodities in the first half of the year. The two trades triggered by my Cycle 9 system between October 2007 and March 2008 netted a combined 22% gain.

The most important point to take away from today is this…

Whenever stocks crash, we’ll be ready… and you can be too!

Click here to make sure you’re on the list to receive my latest research and recommendations.

Adam O’Dell

Editor, Cycle 9 Alert

Follow me on Twitter @InvestWithAdam

The post 3 Ways to Survive the Next Stock Crash appeared first on Economy and Markets.

September 5, 2017

Its Second Demographics D-Day Is Coming

D-Day.

D-Day.

Demographic death day.

Maybe not as bloody as the battlefield in Normandy but equally as devastating in the long term.

And Japan is facing its second one.

Japan’s Baby Boom started to slow down in 1942 coming into World War II and peaked – forever – in 1949 after soldiers came home from war and made a lot of babies.

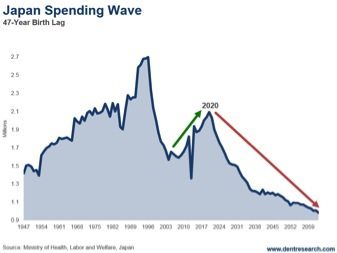

It was the first major developed country to peak on a 47-year lag for spending in its economy. The effects of that first drop-off in births during WWII hit the country after 1989. The second, bigger hit arrived in 1997, and it has felt the negative effects ever since. Look at Japan’s Spending Wave below… Japan has been in an endless slowdown with ever-escalating QE ever since 1997.

Japan has been in an endless slowdown with ever-escalating QE ever since 1997.

Even when its millennial generation turned up mildly around 2003, and its stock market bottomed down 80%, it has only seen a rise back to 21,000 recently. That’s nowhere near its 39,000 peak in late 1989 (a peak we forecast, I’ll add, when we saw the first Demographic D-Day coming and warned of its massive stock and real estate bubbles bursting).

Well, Japan has a second D-Day coming after 2020, right after we likely endure a global market and economic collapse in the next two or three years.

Make no mistake about it: Japan is dying and its demographic decline will only get much worse again after 2020. So, any reprieve in its economy from endless stimulus and super-low interest rates will be short-lived.

Germany is the next to collapse demographically in Europe following Greece, Portugal, and Italy. Spain comes last, but with an equally bitter decline after 2025.

South Korea peaks the last for the East Asia “Tigers” in 2018.

When I lecture in South Korea, my summary statement is that “you are Japan on a 22-year lag.” That’s the difference between their Baby Boom peaks – 1949 and 1971.

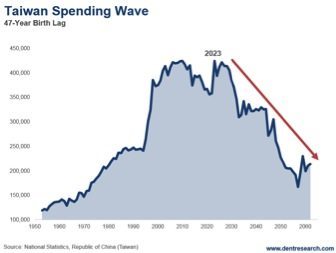

Taiwan, in the chart below, also has already peaked and will see downtrends in consumer spending for decades. This started in 2008 already, but will accelerate after 2023.

The greater part of the developed world has peaked: Japan in late 1996, the U.S. in late 2007, most of Europe in late 2011… and now the rest of East Asia and Japan’s final demographic D-Day.

This is demographic destiny: The greatest global boom in history turns into the greatest bust. Yes! There are cycles in everything. Affluent, urban households have less kids and that reverses the very boom that they created.

If central bankers think they can offset these increasing demographic declines and unprecedented debt levels with “something for nothing” free money – they’re in for a nasty surprise!

Harry

Follow Me on Twitter @harrydentjr

The post Its Second Demographics D-Day Is Coming appeared first on Economy and Markets.

September 4, 2017

What Labor Means in Today’s Gig Economy

Labor Day seems like a foreign concept.

Labor Day seems like a foreign concept.

That’s not to say that I’m unfamiliar with the art of drinking beer while balancing a plate of barbeque as sweat gets in my eyes during the last days of summer. That one I’ve got covered.

I’m referring to the idea of the labor we’re supposed to honor today, at least as I see it in my mind’s eye.

In my head, labor refers to a bunch of people that punch in at a factory or coal mine, put in a long day of work, punch out, and go home. Probably carrying metal lunch pails. Definitely having a cold one when the day is done.

It’s the stuff of posters from the 1930s about the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration (the post office offers commemorative stamps like this… kind of cool).

For the most part, those days are long gone. Fewer than 10% of Americans work in manufacturing, or what we typically think of as “labor.”

The biggest growth industry for employment since the financial crisis has been hospitality, which is a nice way of saying wait staff and bartenders.

In the age of microbreweries, we’ve put millions of people to work asking, “Would you like a hearty, hoppy India Pale Ale that was locally brewed on the western shore of the Mississippi River by brothers who named their company after the local high school sports team?” The taste seems immaterial. It’s all about the label.

I’m not knocking these jobs, but they don’t have quite the same ring as someone who can say, “I build cars.”

Yet it’s where we are.

For decades we’ve transitioned from a world where most people work with physical things to a world where most people provide a service. The best example is the explosion of the gig economy.

I’m old enough to think of a gig as a contract to provide musical entertainment. Performers play gigs. Workers work. Not anymore.

My kids think of gigs as any short-term assignment. No strings, no benefits. Consulting firm McKinsey estimates 68 million people, or roughly 43% of Americans in the workforce, do such freelance work.

Workers who choose to perform work on their terms are happier, we’re told. But 20 million of these folks don’t want to be in such jobs. They do it because they can’t find better paying work elsewhere.

My barber drives for Uber on the weekends. And some weeknights. He’s glad for the chance to earn extra income. Investors have rewarded the company with a $50 billion-plus valuation. I wonder how much of that $50 billion will flow to Uber drivers. Obviously that’s rhetorical. None of it will. Unless they happen to be wealthy angel investors who purchased shares in a private offering and now drive for the company for kicks.

I’m not trying to knock Uber. Or TaskRabbit. Or any other company that facilitates gig work. I’m just noting that the premise makes no sense.

We’re moving toward a world where people are told to celebrate their freedom as mini-entrepreneurs, when the reality is the opposite. It’s true that workers can choose to provide services for such companies, and they aren’t required to take the jobs. But the notion that they could compete with them for business as sole proprietorships is laughable. Employees are free to take the work on the terms provided… or not. And often people choose the work because their primary positions or other opportunities don’t provide enough income.

That’s the labor I see around me today. It’s called the side hustle (really). Everyone seems to be looking for that different income stream that will finally give them enough income, or at least enough stability, to feel secure.

It doesn’t look like a guy with a rivet gun or a sledgehammer. It looks like a woman eating dinner in her car as she travels between her daytime teaching job and her evening appointment for tutoring. It looks like the dental hygienist that also sells real estate, or the construction worker who tends bar on the weekends.

These are the faces of labor. And, chances are, we’ll see many of them today, Labor Day. They won’t be celebrating. They’ll be providing services. They will be showing houses, serving drinks, and even hauling many of us home after we’ve had a few.

So here’s to celebrating those among us that are working harder, and longer, in an economy that seems bent on providing less of some of the things we desire, like security and stability. May they also have the opportunity to rest on this Labor Day, and have a cold one when the day is

Thanks,

Rodney

The post What Labor Means in Today’s Gig Economy appeared first on Economy and Markets.