Julia Flynn Siler's Blog, page 9

March 9, 2012

Rediscovering the Cairo…

Purely by chance, I found myself in the Washington, D.C. neighborhood where Hawai'i's last queen, Lili'uokalani, had once lived.

I was in Washington, D.C. to deliver a talk to a group of Treasury executives about my new book, Lost Kingdom: Hawaii's Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America's First Imperial Adventure. I'd booked a hotel near Dupont Circle.

The evening after the Treasury talk, I was on my way to a dinner party thrown by a group of college friends and stopped at Cairo Wine & Liquor, a small shop a few blocks away from my hotel, to pick up a bottle of wine.

The shop's name caught my eye and I asked the man behind the counter whether the Cairo apartment building was nearby.

"Sure is," he answered, motioning across 17th Street, to 1615 Q Street, N.W. "It's right around the corner."

"That's where Hawai'i's last queen once lived… " I said, as I handed him my credit card.

Historic photo of the Cairo Hotel

I'd visited the building four years ago, early on in my effort to retrace Lili'u's steps. I hadn't remembered where it was, but distinctly remembered the gargoyles on the outside and dramatic Romanesque entry arch.

"Before or after she was kicked off the throne?" he asked, shaking his head.

"Afterwards," I said, a bit surprised that the man at the register, who was perhaps in his late forties, knew the history that had led to the end of the independent Kingdom of Hawaii. I am about his age and this episode of American history was never taught in any of my classes growing up.

I walked out of the shop, having found a connection between a U.S. Marine-backed coup that had taken place 119 years earlier in a remote island kingdom and a Washington, D.C. liquor store.

Lili'u had arrived in the nation's capitol in January of 1897, where she moved into what was then a chic luxury hotel. In her suite of rooms, she penned her autobiography, Hawaii's Story, working closely with the American journalist Julius Palmer in an ultimately unsuccessful effort to regain her throne by swaying public opinion and privately petitioning President Grover Cleveland.

The next morning, I decided to revisit the Cairo – the building, not the liquor store. When it was constructed in 1894, it was the tallest building in Washington, at a soaring 156-feet. Concerns over its safety led the city to pass local height restriction legislation and for many years, it remained the capital's tallest residential building.

When Lili'u moved there in 1897, it had 350 rooms, suites on every floor, a dining room, a grand ballroom, a nightclub, a billiard room, a barbershop, a bowling alley, and (best of all) a tropical garden on its rooftop terrace. In her suite of rooms, Lili'u would work most mornings in front of an open fireplace with a gas log, translating the lyrics of the hundred of so songs she had composed into English, as well as completing her autobiography.

The Cairo went downhill in the decades after Lili'u lived there. As the neighborhood around it decayed in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, it served as a student hostel, a temporary shelter for the needy, and finally, a flophouse. It closed in 1972, was sold and renovated into larger apartments over three years.

In 1993 – the centennial of the overthrow and the same year that President Clinton issued a formal apology to the people of Hawai'i – the Washington Post described the Cairo as sitting like "some massive Byzantine dream" in the midst of a bustling urban neighborhood.

My quick trip to Washington was so much richer for having rediscovered the Cairo. A heartfelt thanks (or mahalo in Hawaiian) to my new friend at the other Cairo (where I bought the bottle of Sonoma-Cutrer) for pointing out this wonderful building.

February 25, 2012

Talking Story at the Outrigger Canoe Club

On my last night in Honolulu on tour for my new book, Lost Kingdom, I was invited for drinks at the Outrigger Canoe Club, which sits at the far end of Waikiki Beach, in the shadow of Diamond Head. The club is a key setting for the novel, The Descendants, which is now an Oscar-nominated film starring George Clooney.

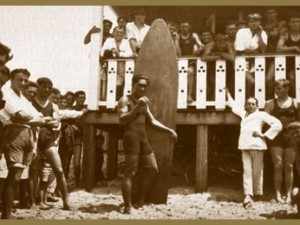

The Outrigger is a small, private club with an outsized history in Hawaii. Founded in 1908, it is the place where legendary surfer Duke Paoa Kahanamoku, a five-time Olympics medalist who competed as a swimmer and water polo player for the U.S. in the 1912, 1920, 1924, and 1932 games. A photo of Duke is mounted on the wood-paneled wall as you enter the dining room, with the words underneath it, "Ambassador of Aloha."

Duke Paoa Kahanamoku on the beach in front of the Outrigger Canoe Club

Our host for drinks that evening was Puchi Romig, the outgoing chairman of the Friends of Iolani Palace, the group that supports the National Historic Monument through fund-raising and other activities. The highlight of her tenure may well have been last fall's Renaissance Ball – the first formal ball at the palace in more than a decade.

One of the guests that joined us that evening at the Outrigger was Marvin "Puakea" Nogelmeier from the University of Hawaii's Manoa campus, who is one of the world's leading experts on the Hawaiian language. I'd had the opportunity to profile Puakea in a front-page story in the Wall Street Journal and had come to like and admire him very much. He has volunteered as a docent at the Palace since the mid-1980s.

Puakea, who had just returned from a trip to New Zealand, had brought with him a copy of his new book, Mai Pa'a I Ka Leo, which is about translating Hawaiian-language newspapers from the nineteenth century into English. He's now deeply involved in a project to do just that – with some 2,500 volunteers pulling together to unlock this potentially huge treasure chest of information, which offers a much deeper look into the Hawaiian perspective from the times than we have today. Even non-Hawaiian speakers can help out: for more information, please visit the project's website.

Puakea had helped me better understand some of the subtleties of the Hawaiian language and had read and commented on the Note on Language that is at the end of Lost Kingdom. He has spent decades studying Hawaiian culture, language and history and, as a relative newcomer, I was grateful for his help, though I recognize that Lost Kingdom, as a popular history, could have benefited from using even more of the new Hawaiian language materials that he and other scholars are uncovering every day.

Puchi's other guest was another true descendant, in her own way similar to Princess Abigail Kawananakoa, with whom I'd had lunch when I first arrived. She was Robin Midkiff, a Punahou and Stanford graduate who was a descendant of one of the most prominent missionary families. She is related to Juliette and Amos Starr Cooke, a missionary couple who taught Liliuokalani and other royal students at the Chief's Children's School in the 1830s and 1840s in Honolulu.

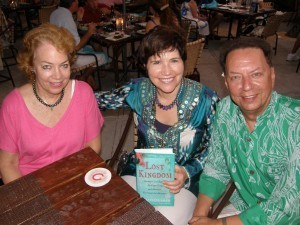

Robin Midkiff, Julia Flynn Siler, and Puakea Nogelmeier at the Outrigger Canoe Club

Robin is also related to Paul Neumann, an attorney who began his career in California but moved to Honolulu in the early 1880s, quickly rising to the position of the kingdom's attorney general under King David Kalakaua. Neumann represented the last queen, Liliuokalani, at her military trial in 1895 and witnessed her forced abdication. To honor him, the deposed Queen and her lady-in-waiting had stitched his name into the Victorian era crazy quilt that they worked on together during Liliu's eight months of house arrest at the palace.

In addition to working as a senior executive at the First Hawaiian Bank and serving as a member of the Atherton Family Foundation, Robin is deeply involved in preserving the history of Hawaii in her role as chairman of the Washington Place Foundation, the group formed to support the gracious, white pillared home in downtown Honolulu where Liliu spent most of her life. The deposed queen died at Washington Place in 1917 and it long served as the official residence for Hawaii's Governor. In 2007, it was designated as a National Historic Landmark.

We watched for a green flash as the sun sank into the Pacific. Puakea and Robin talked history about the early days of Kamehameha I and his bloody conquest of the island of Oahu. As I sat between them listening to their conversation, I thought to myself how I'd never known a place where history lies so close to the surface of daily life – with reminders every day in the street names reflecting the days when the islands were ruled by Hawaiian royalty.

January 28, 2012

The Queen’s Speech

Dear readers,

Here’s a Q&A from the Honolulu Weekly that I wanted to share with you. It’s in the current issue (Jan. 25-31) of the newspaper and I’ve gotten a number of comments on it already. Please let me know what you think.

***

The Queen’s Speech by Don Wallace

As the principals of The Descendants prepare to stroll down Oscar’s red carpet, and the 119th anniversary of Queen Liliuokalani’s overthrow is observed, a major and masterful new book about Hawaii hits the shelves. Julia Flynn Siler’s Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure, is big, scholarly and highly readable. In it, Siler traces the shady land transactions, the snares of debt and the extra-legal maneuvers that strangled the Hawaiian nation in its crib. Scrupulously fair-minded, she also doesn’t spare the monarchy, the alii and the court advisors their follies, such as King Kalakaua’s attempt to seize Samoa with a one-ship navy. But the cool telling and preponderance of evidence leave no doubt in the reader’s mind where the blame, and shame, ultimately belong.

DW: This is a deeply researched book, filled with illuminating details. Can you describe some of your discoveries?

JFS: In the four years I spent researching and writing this book, I tracked down pages from the royal cashbooks detailing loans to King David Kalakaua from Claus Spreckels, the Gilded Age tycoon known as the “Sugar King.” The king’s indebtedness was one of the reasons that his sister, Liliuokalani, ended up in such a difficult position when she ascended to the throne in 1891. I also found letters and other documents that offered glimpses of Liliu’s personality—her moments of scolding her sister for being flirtatious and her wifely pique at her husband for not picking up the fish she wanted, for example, as well as her diary entries which recorded the hot anger she felt at the white men who held her captive in her own palace.

DW: Any other surprises?

JFS: At the Bishop Museum archives, I found a page that Liliu had torn from the Book of Psalms. She had written in pencil: “Iolani Palace. Jan 16th 1895. Am imprisoned in this room (the South east corner) by the Government of the Hawaiian Republic. For the attempt of the Hawaiian people to regain what had been wrested from them by the children of the missionaries who first brought the Word of God to my people.” Finding that yellowed page, which she had presumably torn out of the Bible and written on during the first night of her imprisonment after a failed counter-coup, gave me chicken skin.

DW: What were other influential sources?

JFS: Meeting David Forbes, who is a leading bibliographer of Hawaiian history, influenced the shape of my book. He’d recently finished a many-year project to collect and transcribe every letter and document he could find involving members of the Hawaiian royal family. He gave me early access to that collection, which he’d generously donated to the Hawaii State Archives. Some of those letters have never been published before.

DW: In the Wall Street Journal, you recently wrote about the legal issues underlying The Descendants.

JFS: The filmmakers reached out to University of Hawaii law professor Randall W. Roth and others to drill down on the legal issues underlying the plot. Roth provided guidance on trust law to the filmmakers, particularly on the somewhat arcane subject of the rule against perpetuities. It’s a key point in the plot. Matt King and the other descendants of a Hawaiian princess and haole banker have inherited a piece of land, which is held in trust. They must decide whether to sell it because the trust itself, under the rule, must be wound down by a set date.

DW: Can you comment on parallels between 1893 and now? An economic depression. Gambling on the legislative agenda. The economy dependent on sugar then, tourism now. The American military presence growing.

JFS: Interesting comparison. Do you think we’re heading towards a new “Committee of Safety”?

DW: Maybe the fruition of the old one. Was Liliuokalani handed a similar bum set of cards to Obama’s in 2009?

JFS: No doubt, they both faced serious challenges when they took power. The difference is that Queen Liliuokalani was set up to fail in almost every respect, while President Obama, who entered office inheriting two wars and a global economic crisis that threatened to topple the US financial system, also had powerful political momentum on his side and a strong electoral mandate. Although President Obama’s critics would surely like to stage a coup against him, he’s still in office and may be again for another four years.

DW: When Liliuokalani attended Queen Victoria’s Silver Jubilee, you say she was influenced by the lavish spectacle and the power and respect accorded this tiny woman at the center of the world’s greatest empire. Did she recognize Victoria’s position as largely symbolic?

JFS: Queen Liliuokalani combined a western view of the somewhat limited role of a constitutional monarch with the ancient Hawaiian reverence for the alii–the high chiefs who held absolute power over the commoners. The view of the kingdom’s largely white business class was that she should just be a figurehead. She hoped to restore some semblance of real power to her position by introducing a new constitution in January of 1893—a move that became a pretext for her overthrow.

DW: Was there ever a chance Hawaii would emerge a sovereign nation from the colonial squeeze play between Great Britain, America and Germany?

JFS: Sadly, I think that was unlikely, given its strategic position in the Pacific. It was only a matter of time before it was swallowed up by a superpower. As the prescient nineteenth-century Hawaiian historian, David Malo predicted, “they will eat us up, such has always been the case with large countries, the small ones have been gobbled up.”

DW: How disastrous was King Kalakaua’s military adventurism in Samoa?

JFS: It was a public relations disaster for him—his enemies turned it into a propaganda victory against him and the Hawaiian monarchy. But considering the energetic empire-building that was going on in the rest of the world at the time, it was truly a small matter.

DW: How significant was Liliu’s talk of beheading the plotters of the overthrow?

JFS: The challenge of writing history is that you can’t ask your subjects to explain themselves. In this case, her statement about having her enemies “beheaded” was in the form of a conversation she’d had with a US envoy. That envoy then wrote down his dialogue with the queen in a memorandum and Liliuokalani signed it, attesting to its truth. Here were her words as reported in the memorandum: “There are certain laws of my government by which I shall abide. My decision would be, as the law directs, that such persons should be beheaded and their property confiscated to the Government.” My guess is that she spoke out of anger because she later retracted what she’d said. However, just as her brother’s Samoan misadventure was used against him, Liliu’s angry words were used against her.

DW: As author of a book about America’s first family of wine, the Mondavis, do you see similarities to the Spreckels sugar family?

JFS: Both in their talent for business and their passionate disagreements with each other, the Spreckels were the nineteenth century version of the Mondavis.

DW: Do you see a parallel between the Mondavi sibling rivalries and those among the Hawaiian royal lines leading up to the overthrow?

JFS: Yes, there are parallels. But I challenge you to name a single dynasty—royal or otherwise—where there aren’t sibling rivalries or succession issues. These conflicts just seem to be part of human nature, though they stand out more clearly in cases where the families are powerful.

The Queen's Speech

Dear readers,

Here's a Q&A from the Honolulu Weekly that I wanted to share with you. It's in the current issue (Jan. 25-31) of the newspaper and I've gotten a number of comments on it already. Please let me know what you think.

***

The Queen's Speech by Don Wallace

As the principals of The Descendants prepare to stroll down Oscar's red carpet, and the 119th anniversary of Queen Liliuokalani's overthrow is observed, a major and masterful new book about Hawaii hits the shelves. Julia Flynn Siler's Lost Kingdom: Hawaii's Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America's First Imperial Adventure, is big, scholarly and highly readable. In it, Siler traces the shady land transactions, the snares of debt and the extra-legal maneuvers that strangled the Hawaiian nation in its crib. Scrupulously fair-minded, she also doesn't spare the monarchy, the alii and the court advisors their follies, such as King Kalakaua's attempt to seize Samoa with a one-ship navy. But the cool telling and preponderance of evidence leave no doubt in the reader's mind where the blame, and shame, ultimately belong.

DW: This is a deeply researched book, filled with illuminating details. Can you describe some of your discoveries?

JFS: In the four years I spent researching and writing this book, I tracked down pages from the royal cashbooks detailing loans to King David Kalakaua from Claus Spreckels, the Gilded Age tycoon known as the "Sugar King." The king's indebtedness was one of the reasons that his sister, Liliuokalani, ended up in such a difficult position when she ascended to the throne in 1891. I also found letters and other documents that offered glimpses of Liliu's personality—her moments of scolding her sister for being flirtatious and her wifely pique at her husband for not picking up the fish she wanted, for example, as well as her diary entries which recorded the hot anger she felt at the white men who held her captive in her own palace.

DW: Any other surprises?

JFS: At the Bishop Museum archives, I found a page that Liliu had torn from the Book of Psalms. She had written in pencil: "Iolani Palace. Jan 16th 1895. Am imprisoned in this room (the South east corner) by the Government of the Hawaiian Republic. For the attempt of the Hawaiian people to regain what had been wrested from them by the children of the missionaries who first brought the Word of God to my people." Finding that yellowed page, which she had presumably torn out of the Bible and written on during the first night of her imprisonment after a failed counter-coup, gave me chicken skin.

DW: What were other influential sources?

JFS: Meeting David Forbes, who is a leading bibliographer of Hawaiian history, influenced the shape of my book. He'd recently finished a many-year project to collect and transcribe every letter and document he could find involving members of the Hawaiian royal family. He gave me early access to that collection, which he'd generously donated to the Hawaii State Archives. Some of those letters have never been published before.

DW: In the Wall Street Journal, you recently wrote about the legal issues underlying The Descendants.

JFS: The filmmakers reached out to University of Hawaii law professor Randall W. Roth and others to drill down on the legal issues underlying the plot. Roth provided guidance on trust law to the filmmakers, particularly on the somewhat arcane subject of the rule against perpetuities. It's a key point in the plot. Matt King and the other descendants of a Hawaiian princess and haole banker have inherited a piece of land, which is held in trust. They must decide whether to sell it because the trust itself, under the rule, must be wound down by a set date.

DW: Can you comment on parallels between 1893 and now? An economic depression. Gambling on the legislative agenda. The economy dependent on sugar then, tourism now. The American military presence growing.

JFS: Interesting comparison. Do you think we're heading towards a new "Committee of Safety"?

DW: Maybe the fruition of the old one. Was Liliuokalani handed a similar bum set of cards to Obama's in 2009?

JFS: No doubt, they both faced serious challenges when they took power. The difference is that Queen Liliuokalani was set up to fail in almost every respect, while President Obama, who entered office inheriting two wars and a global economic crisis that threatened to topple the US financial system, also had powerful political momentum on his side and a strong electoral mandate. Although President Obama's critics would surely like to stage a coup against him, he's still in office and may be again for another four years.

DW: When Liliuokalani attended Queen Victoria's Silver Jubilee, you say she was influenced by the lavish spectacle and the power and respect accorded this tiny woman at the center of the world's greatest empire. Did she recognize Victoria's position as largely symbolic?

JFS: Queen Liliuokalani combined a western view of the somewhat limited role of a constitutional monarch with the ancient Hawaiian reverence for the alii–the high chiefs who held absolute power over the commoners. The view of the kingdom's largely white business class was that she should just be a figurehead. She hoped to restore some semblance of real power to her position by introducing a new constitution in January of 1893—a move that became a pretext for her overthrow.

DW: Was there ever a chance Hawaii would emerge a sovereign nation from the colonial squeeze play between Great Britain, America and Germany?

JFS: Sadly, I think that was unlikely, given its strategic position in the Pacific. It was only a matter of time before it was swallowed up by a superpower. As the prescient nineteenth-century Hawaiian historian, David Malo predicted, "they will eat us up, such has always been the case with large countries, the small ones have been gobbled up."

DW: How disastrous was King Kalakaua's military adventurism in Samoa?

JFS: It was a public relations disaster for him—his enemies turned it into a propaganda victory against him and the Hawaiian monarchy. But considering the energetic empire-building that was going on in the rest of the world at the time, it was truly a small matter.

DW: How significant was Liliu's talk of beheading the plotters of the overthrow?

JFS: The challenge of writing history is that you can't ask your subjects to explain themselves. In this case, her statement about having her enemies "beheaded" was in the form of a conversation she'd had with a US envoy. That envoy then wrote down his dialogue with the queen in a memorandum and Liliuokalani signed it, attesting to its truth. Here were her words as reported in the memorandum: "There are certain laws of my government by which I shall abide. My decision would be, as the law directs, that such persons should be beheaded and their property confiscated to the Government." My guess is that she spoke out of anger because she later retracted what she'd said. However, just as her brother's Samoan misadventure was used against him, Liliu's angry words were used against her.

DW: As author of a book about America's first family of wine, the Mondavis, do you see similarities to the Spreckels sugar family?

JFS: Both in their talent for business and their passionate disagreements with each other, the Spreckels were the nineteenth century version of the Mondavis.

DW: Do you see a parallel between the Mondavi sibling rivalries and those among the Hawaiian royal lines leading up to the overthrow?

JFS: Yes, there are parallels. But I challenge you to name a single dynasty—royal or otherwise—where there aren't sibling rivalries or succession issues. These conflicts just seem to be part of human nature, though they stand out more clearly in cases where the families are powerful.

January 25, 2012

Book Group Pick: Lost Kingdom

Mahalo nui loa – Hawaiian for thank you very much! – to the half dozen or so book groups I've heard from around the country that have picked Lost Kingdom as their monthly or quarterly read. I'm truly grateful to all of you – from Liz Epstein's Literary Masters groups (10 book groups in the San Francisco Bay Area) to Catherine Hartman's lovely group of Stanford alum and other book-loving friends in Chicago to Jason Poole (The Accidental Hawaiian Crooner) who also organizes a reading group in Pittsburgh. Here are some questions to discuss on Lost Kingdom that come from Liz Epstein at Literary Masters. Hope they're helpful and if you have other questions, I'd be delighted to skype or phone into your book group for a chat if my schedule permits.

[image error]

Points to Ponder for Lost Kingdom

Whose story is Lost Kingdom and who should be telling it? Do you think Julia Flynn Siler, a haole or white foreigner to the islands, does a good job of showing all sides of this story about nineteenth century Hawaii? Do you think it is an important story?

Is there a hero/heroine or villain/villainess in this story?

How do you feel about Lili'u? Could she have done anything to alter the course of historical events? Should she have? Do you consider her a tragic figure?

How do you feel about King David Kalakaua? How responsible was he for the course of events?

How do you feel about the way the United States handled the annexation of Hawaii? Grover Cleveland claimed "Hawaii is ours…as I contemplate the means used to complete the outrage, I am ashamed of the whole affair." Do you agree/ disagree with him?

How do you feel about the way the Hawaiians handled the annexation of Hawaii? Did you get a good sense from the book as to how and why they behaved as they did?

What surprised you about Claus Spreckels? What about Dole? Are there other characters in the book that you feel played a pivotal role and you'd like to know more about them?

What were the motives of the original missionaries in coming to Hawaii, and then how do you feel about their descendents? Was everyone generally well-intentioned, or was self-interest paramount?

What is the relevance of this history for us today?

Can you imagine an alternate history? Where would Hawaii be today if the US hadn't annexed it? Where would the US be today without Hawaii?

This was our non-fiction selection for the season. Do you think this particular history of Hawaii could be better told as 'historical fiction'?

January 17, 2012

Surf’s Up

The famed Mavericks Surf Contest, which takes place in Half Moon Bay, California, is called each year by its organizers only when conditions are right. Last year, the waves were never big enough for the competition to take place. This year, it began on January 3rd, 2012, the same day as the publication date for my new book, Lost Kingdom.

[image error]

That coincidence gave me some pleasure, since surfing, known as he‘e nalu or surf riding in the Hawaiian language, is one of the few aspects of ancient Hawaiian culture that have thrived beyond the reef – with Hawaiians themselves bringing the sport at the turn of the twentieth century to America. And one of the parts of my book I loved researching the most was the history of Hawaiian surfing, which was known as the sport of kings, also known as the ali‘i, or high chiefs.

Because commoners worked in the fields and tended the fish ponds, the ali‘i could devote themselves to sports. Their favorite pastime was surfing and they rode the waves on enormous, carved wood boards—some more than eighteen feet long and weighing 150 pounds. Both male and female chiefs also excelled at related sports such as canoe-leaping, in which the surfer would jump from a canoe carrying his or her board into a cresting ocean swell, and then ride the wave to the shore.

When the surf was high, entire villages rushed to the beach. Men, women, and children would paddle out to ride the rolling waves. While Tahitians and other Pacific Islanders also surfed, the Hawaiians took the sport to a higher level—standing fearlessly on their massive boards, often three times as long as those used elsewhere in Polynesia.

The Hawaiians were magnificent athletes. Some excelled at cliff- diving into the sea, from heights of many hundreds of feet. Even young women would strip naked and leap from the summit of high cliffs, diving headlong into the foaming water and bobbing up afterward. One can only imagine their dark hair streaming down their shoulders and their faces beaming with delight.

One of my finds in digging through archives was an engraving of ancient surfers, as well as nineteenth and early twentieth century photographs of the sport. But for those of you who don’t have the time or inclination to visit the State Archives of Hawaii in Honolulu but want to learn more about the history of surfing, I’d suggest a wonderful book called Surfing: A History of the Ancient Sport, which was co-authored by Ben R. Finney and the late James D. Houston. I found a copy in our local library. I also loved DeSoto Brown’s Surfing: Historic Images from the Bishop Museum Archives.

As for getting out on the water, I’m more of an upright paddle or kayak girl myself – and maybe a boogie boarder if conditions are just right. But I’m heading to Honolulu later this spring and hope to finally take the surf lesson I’d been promising myself while I sat in darkened archives. Cowabunga!

Surf's Up

The famed Mavericks Surf Contest, which takes place in Half Moon Bay, California, is called each year by its organizers only when conditions are right. Last year, the waves were never big enough for the competition to take place. This year, it began on January 3rd, 2012, the same day as the publication date for my new book, Lost Kingdom.

[image error]

That coincidence gave me some pleasure, since surfing, known as he'e nalu or surf riding in the Hawaiian language, is one of the few aspects of ancient Hawaiian culture that have thrived beyond the reef – with Hawaiians themselves bringing the sport at the turn of the twentieth century to America. And one of the parts of my book I loved researching the most was the history of Hawaiian surfing, which was known as the sport of kings, also known as the ali'i, or high chiefs.

Because commoners worked in the fields and tended the fish ponds, the ali'i could devote themselves to sports. Their favorite pastime was surfing and they rode the waves on enormous, carved wood boards—some more than eighteen feet long and weighing 150 pounds. Both male and female chiefs also excelled at related sports such as canoe-leaping, in which the surfer would jump from a canoe carrying his or her board into a cresting ocean swell, and then ride the wave to the shore.

When the surf was high, entire villages rushed to the beach. Men, women, and children would paddle out to ride the rolling waves. While Tahitians and other Pacific Islanders also surfed, the Hawaiians took the sport to a higher level—standing fearlessly on their massive boards, often three times as long as those used elsewhere in Polynesia.

The Hawaiians were magnificent athletes. Some excelled at cliff- diving into the sea, from heights of many hundreds of feet. Even young women would strip naked and leap from the summit of high cliffs, diving headlong into the foaming water and bobbing up afterward. One can only imagine their dark hair streaming down their shoulders and their faces beaming with delight.

One of my finds in digging through archives was an engraving of ancient surfers, as well as nineteenth and early twentieth century photographs of the sport. But for those of you who don't have the time or inclination to visit the State Archives of Hawaii in Honolulu but want to learn more about the history of surfing, I'd suggest a wonderful book called Surfing: A History of the Ancient Sport, which was co-authored by Ben R. Finney and the late James D. Houston. I found a copy in our local library. I also loved DeSoto Brown's Surfing: Historic Images from the Bishop Museum Archives.

As for getting out on the water, I'm more of an upright paddle or kayak girl myself – and maybe a boogie boarder if conditions are just right. But I'm heading to Honolulu later this spring and hope to finally take the surf lesson I'd been promising myself while I sat in darkened archives. Cowabunga!

January 3, 2012

My Dissenting Opinion on “The Descendants” — a guest blog by Constance Hale

My friend, Connie Hale, grew up in Hawaii and was educated at Punahou (the elite college prep school that is also Barack Obama’s alma mater.) From there, she earned a bachelor’s degree in English from Princeton University and a masters in journalism from U.C. Berkeley. She is now a gifted author, journalist, and editor who works at San Francisco’s famed Writers’ Grotto. I’m honored to run this guest blog by Connie on the Alexander Payne film, “The Descendants,” which is set in Hawaii. Here’s her thought-provoking take on the film and the many issues surrounding land, power, and one-percenters in the Aloha State.

***

By Constance Hale

Folks who know I grew up in Hawaii have inquired about my response to The Descendants. At the risk of sounding dyspeptic, here it is. First, if you evaporate all the Hawaii stuff out, you’ve got a pretty banal story, albeit a tearjerker. “Back-up” dad (aka George Clooney), alienated kids, failing marriage, loss that brings kids closer to dad.

Now put the Hawaii subplot back in. Kudos to the filmmaker for giving slight attention to the tragic political history of Hawaii, and hooray that the character Matt King doesn’t sell out–yet.

But auwe! (Translation: alas! bummer! too bad!) This film over-focuses on the rarefied lives of Hawaiian one-percenters, instead of the real lives and real concerns of 1) folks with more connection to their Native Hawaiian roots than Matt King; 2) folks who don’t get to live in glorious houses in Nu’uanu Valley and send their kids to expensive schools; 3) the racially interesting, socioeconomically diverse, medically and psychically vulnerable hoi polloi that are shown in the first few minutes of the film, then abandoned.

What isn’t touched in this film: The larger story of the ways that the deeds and misdeeds of Hawaiian royalty, New England missionaries, and the haole oligarchy left bruises still tender to the touch. The story of how a determined band of haole are suing Hawaiian institutions like the Kamehameha Schools to get a share of the very small privileges Native Hawaiian still enjoy after having lost their land, their communal way of life, their full access to mountains, shorelines, waters. The story of how some Native Hawaiians are trying to wrest back some sort of sovereignty analogous to that held by other Native Americans and how other Native Hawaiians are making sure that music and dance and language come roaring back from near extinction.

The film might also have quoted the state motto–Ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (“The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness”) or probed the deeply esoteric Hawaiian notion of “pono.” (I prefer to translate the word as “moral correctness,” which doesn’t carry the Christian overtones of “righteousness.”) A more adept filmmaker might have jettisoned certain comedic touches (Clooney’s full head of gray hair floating over an ironwood hedge the way a coconut floats on the water) in favor of more artfully exploring the idea that only if we are all good stewards of the land, from which Hawaiians believe all culture flows, can we ensure that what is truly magical about Hawaii endures.

OK, it’s not fair to expect a film to do this much, but I would have been happy with more layers in the story.

All that said, I thought that the depiction of surfer-dude adults, denizens of the Outrigger Canoe club, students at Hawaii Prep and Punahou was spot on. So was the depiction of life at the top for families like the Kings: they live like that, they talk like that, they dress like that. (The only false note: Matt King wore topsiders instead of slippers–”flip flops” to you mainlanders. No self-respecting islander wears those preppie moccasins.)

And the best thing: the film features some of the unbelievably good Hawaiian music that remains unknown to most mainlanders–I hope this film helps change that. I loved loved loved the scene in that bar in Hanalei with the musician’s cousin singing in falsetto. That was pretty authentic, though you probably won’t find it in Hanalei. I’ve spent two separate reporting trips looking for Hawaiian music in Hanalei hotels, restaurants, and bars and can say it’s mostly absent. There is, though, a wonderful (haole) couple who play and talk slack-key on Friday and Sunday afternoons at the Hanalei Community Center: Doug and Sandy McMaster.

Let’s hope Kaui Hart Hemmings writes another novel set in Hawaii, showing yet another dimension of life in the islands, and that another filmmaker chooses to make it.

Imua! (Let’s keep moving forward!)

[image error]

You didn’t see the taro patches of Hanalei in the movie, but they are a hugely important part of Hanalei and one of the signs that Native Hawaiians still have a foothold here.

Like · · Share

My Dissenting Opinion on "The Descendants" — a guest blog by Constance Hale

My friend, Connie Hale, grew up in Hawaii and was educated at Punahou (the elite college prep school that is also Barack Obama's alma mater.) From there, she earned a bachelor's degree in English from Princeton University and a masters in journalism school from U.C. Berkeley. She is now a gifted author, journalist, and editor who works at San Francisco's famed Writers' Grotto. I'm honored to run this guest blog by Connie on the Alexander Payne film, "The Descendants," which is set in Hawaii. Here's her thought-provoking take on the film and the many issues surrounding land, power, and one-percenters in the Aloha State.

***

By Constance Hale

Folks who know I grew up in Hawaii have inquired about my response to The Descendants. At the risk of sounding dyspeptic, here it is. First, if you evaporate all the Hawaii stuff out, you've got a pretty banal story, albeit a tearjerker. "Back-up" dad (aka George Clooney), alienated kids, failing marriage, loss that brings kids closer to dad.

Now put the Hawaii subplot back in. Kudos to the filmmaker for giving slight attention to the tragic political history of Hawaii, and hooray that the character Matt King doesn't sell out–yet.

But auwe! (Translation: alas! bummer! too bad!) This film over-focuses on the rarefied lives of Hawaiian one-percenters, instead of the real lives and real concerns of 1) folks with more connection to their Native Hawaiian roots than Matt King; 2) folks who don't get to live in glorious houses in Nu'uanu Valley and send their kids to expensive schools; 3) the racially interesting, socioeconomically diverse, medically and psychically vulnerable hoi polloi that are shown in the first few minutes of the film, then abandoned.

What isn't touched in this film: The larger story of the ways that the deeds and misdeeds of Hawaiian royalty, New England missionaries, and the haole oligarchy left bruises still tender to the touch. The story of how a determined band of haole are suing Hawaiian institutions like the Kamehameha Schools to get a share of the very small privileges Native Hawaiian still enjoy after having lost their land, their communal way of life, their full access to mountains, shorelines, waters. The story of how some Native Hawaiians are trying to wrest back some sort of sovereignty analogous to that held by other Native Americans and how other Native Hawaiians are making sure that music and dance and language come roaring back from near extinction.

The film might also have quoted the state motto–Ua mau ke ea o ka 'aina i ka pono ("The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness") or probed the deeply esoteric Hawaiian notion of "pono." (I prefer to translate the word as "moral correctness," which doesn't carry the Christian overtones of "righteousness.") A more adept filmmaker might have jettisoned certain comedic touches (Clooney's full head of gray hair floating over an ironwood hedge the way a coconut floats on the water) in favor of more artfully exploring the idea that only if we are all good stewards of the land, from which Hawaiians believe all culture flows, can we ensure that what is truly magical about Hawaii endures.

OK, it's not fair to expect a film to do this much, but I would have been happy with more layers in the story.

All that said, I thought that the depiction of surfer-dude adults, denizens of the Outrigger Canoe club, students at Hawaii Prep and Punahou was spot on. So was the depiction of life at the top for families like the Kings: they live like that, they talk like that, they dress like that. (The only false note: Matt King wore topsiders instead of slippers–"flip flops" to you mainlanders. No self-respecting islander wears those preppie moccasins.)

And the best thing: the film features some of the unbelievably good Hawaiian music that remains unknown to most mainlanders–I hope this film helps change that. I loved loved loved the scene in that bar in Hanalei with the musician's cousin singing in falsetto. That was pretty authentic, though you probably won't find it in Hanalei. I've spent two separate reporting trips looking for Hawaiian music in Hanalei hotels, restaurants, and bars and can say it's mostly absent. There is, though, a wonderful (haole) couple who play and talk slack-key on Friday and Sunday afternoons at the Hanalei Community Center: Doug and Sandy McMaster.

Let's hope Kaui Hart Hemmings writes another novel set in Hawaii, showing yet another dimension of life in the islands, and that another filmmaker chooses to make it.

Imua! (Let's keep moving forward!)

[image error]

You didn't see the taro patches of Hanalei in the movie, but they are a hugely important part of Hanalei and one of the signs that Native Hawaiians still have a foothold here.

Like · · Share

December 6, 2011

Remembering Pearl Harbor: How a Gilded Age Scoundrel Waged a War of Words over the estuary that became Pearl Harbor

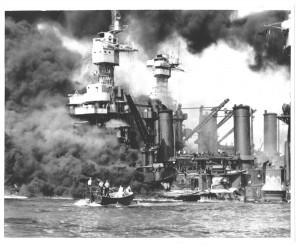

In the early hours of Sunday, December 7, 1941, seventy years ago, Japanese bombers launched a surprise attack against the US military base at Pearl Harbor. The devastating attack on Hawaii, which was then an American territory, profoundly shook the nation and hastened its entry into World War II.

Attack on the USS Arizona on December 7, 1941 Photo courtesy of the National Park Service Archives

But nearly seven decades before "Remember Pearl Harbor" became a national rallying cry, the same waters were a battleground over Hawaiian sovereignty. In the 19th century, Hawaii was an independent nation — a constitutional monarchy modeled on Great Britain's — as well as a reluctant bride in a contest among the era's reigning and rising superpowers. In it, they saw the potential for a deep water port that would make Hawaii an ideal stopover for large ships traveling between North America and Asia.

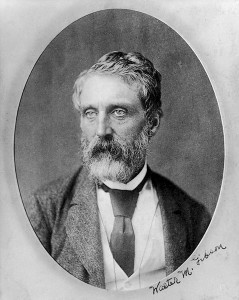

Native Hawaiians rightly feared that they would lose their nation if they ceded rights to the Pearl River area, which they called Pu'uloa. They found an unlikely champion in a tall, blue-eyed American adventurer named Walter Murray Gibson. A Southerner with a murky past, he had arrived in the islands in 1861 as a Mormon missionary. With a genius for spotting opportunity, he took up the quixotic cause of saving the Pearl River basin.

Walter Murray Gibson, from the Honolulu Advertiser

He entered the seething and unstable political scene of the island nation's capital of Honolulu in 1872, the year of King Kamehameha V's death. Fluent in Hawaiian, he had renounced his U.S. citizenship to become a citizen of the Hawaiian Kingdom. When impassioned debates over the fate of the Pearl River basin, an area which was about a day-long carriage ride to the northwest from Honolulu, became front page news, Gibson started using the pages of his own Hawaiian-language newspaper to espouse the populist message of "Hawaii for Hawaiians."

The basin had deep cultural resonance for Hawaiians, whose ancient ancestors believed that the shark goddess Ka'ahupahau guarded the Pearl River's treacherous entrance, a narrow channel through coral reefs where saltwater mingled with fresh. It was the wealth of oyster beds that gave the area its English name and native Hawaiians had long dived for these prizes in the harbor's waters.

But the Pearl River basin lured a succession of British and American naval officers carrying magnetic compasses and surveyor's chains, and in 1873 a military commission under secret instructions from the US secretary of war William W. Belknap examined various ports in the Hawaiian Islands for possible defensive and commercial purposes. That same year, King William Lunalilo became the first Hawaiian monarch to give serious consideration to a proposal from the US offering the harbor in exchange for allowing Hawaiian sugar (which planters began cultivating in the 1870s) to enter the American market duty-free. Trade and defense were becoming inextricably bound, and in neither case were native Hawaiians reaping the potential benefits: The vast majority of the Hawaiian planters who stood to benefit from the agreement were, in fact, white foreigners.

Aerial view of Pearl Harbor, prior to attack. Photo courtesy of National Park Service Archives

In his public statements, David Kalākaua, who ascended to the throne in early 1874, had long been opposed to ceding rights to the Pearl River basin. Likewise, Gibson argued against giving the estuary to the United States, and in November of 1873, he printed a traditional Hawaiian chant, or *mele*, expressing Hawaiian opposition to the deal, which would give the U.S. exclusive access to the estuary in exchange for trade benefits. It ended with the warning:

Be not deceived by the merchants,

They are not only enticing you,

Making fair their faces, they are evil within;

Truly desiring annexation,

For several more years the basin remained in Hawaiian possession. But Gibson and King Kalākaua could only hold off the diplomats, politicians, and powerful sugar planters for so long. In 1887, in the midst of an economic depression and intense pressure from the nation's businessmen, a Reciprocity Treaty was signed which gave the United States exclusive rights to the area in exchange for trade benefits for exporters of Hawaiian goods to the states. The editorial writers of the kingdom's Hawaiian language newspapers reacted with dismay, particularly Joseph Nāwahī, a respected native journalist and legislator. He had predicted in 1876 that reciprocity "would be the first step of annexation later on, and the Kingdom, its flag, its independence, and its people will be naught."

The king's sister, Lili'uokalani, was likewise distressed by the deal with the Americans. On Monday, September 26, 1887, she wrote in her diary, "King signed a lease of Pearl river to U. States for eight years to get R. Treaty." Seeing the lease as an unequal swap for a treaty that benefited the island kingdom's sugar planters, she concluded darkly, "It should not have been done."

Gibson, meanwhile, fled the country amidst corruption charges aboard a San Francisco bound steamer owned by the kingdom's leading sugar planter, Claus Spreckels. He had barely escaped hanging by an angry mob. Ailing and exhausted, he sought to commit his version of events to paper, since he felt the "reformers" who had chased him out of Honolulu had ignored his years of faithful service to the Hawaiian people and his brave, but increasingly unpopular, defense of their interests. He died a few months later in San Francisco. According to the newspapers who reported his death, his last word was "Hawai'i."

Gibson's embalmed body returned to the islands covered with a Hawaiian flag. Once it arrived, streams of visitors came to view the body, including some of Gibson's fiercest critics: Judge Sanford B. Dole, his brother George Dole, and Lorrin Thurston, who would later lead the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The three men joined the crowd moving past his coffin. Thurston was shocked to see that the embalming fluid had turned Gibson's skin very dark, eerily contrasting with his long white beard and silver locks. They left the reception room and stepped out onto the street.

"What do you think of it?," Dole asked his brother and Thurston. After a few seconds' pause, George answered, "Well, I think his complexion is approximating the color of his soul."

Today, Gibson is nearly forgotten. Pearl Harbor, as it exists today, was created following massive dredging of the basins coral reefs in the 20th century. The US naval base at Pearl Harbor is headquarters to the commander of the Pacific Fleet, the world's largest, responsible for patrolling a hundred million square miles of ocean.

Julia Flynn Siler is the author "Lost Kingdom: Hawai'i's Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America's First Imperial Adventure," published by Atlantic Monthly Press. For more information, please visit www.juliaflynnsiler.com.