Julia Flynn Siler's Blog, page 8

September 2, 2012

The Queen and the Clevelands (Grover and George…)

Today is the birthday of Hawai’i's last reigning monarch, Lili’uokalani. Born in a grass house on September 2, 1838 and adopted by Hawai’i's ruling dynasty, the infant girl who would become Hawai’i's last queen began her tumultuous life 174 years ago at the base of an extinct volcano in Honolulu.

Queen Lili’uokalani, Hawai’i State Archives

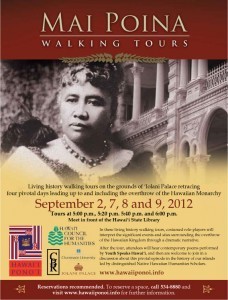

For the past several years, historians, Hawaiian cultural practitioners, and others who keep Lili‘uokalani’s memory alive, have gathered at the grounds of ‘Iolani Palace on her birthday to lead walking historical walking tours in an event called Mai Poina (Don’t Forget.) The first tour start today at 5:00 p.m. the Hawai’i State Library. It’s already sold out — but there are still a few spots left for these free tours the following weekend.

This year’s Mai Poina is set to be a very unusual one. According to a story in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, President Grover Cleveland’s grandson, George Cleveland, is visiting Hawaii this weekend to celebrate Lili‘uokalani’s birthday. As part of that trip, he will take part in the Mai Poina re-enactment of the overthrow on the palace grounds.

Grover Cleveland, who was the newly elected Democratic president at the time of the overthrow, had doubts about what had happened over those four days in 1893 in the far-away independent kingdom of Hawai’i.

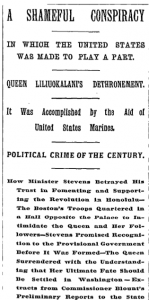

He hastily withdrew the Hawaiian annexation treaty, which his successor, Republican President Harrison, had hoped to push through before leaving office and appointed a special commissioner to investigate the matter that a New York Times headline decried as the “Political Crime of the Century.”

New York Times coverage of the overthrow in 1893

But partisan politics and heavy lobbying on the part of pro-annexation forces bogged down the question of restoring Liliuokalani to the throne. Not long after Cleveland’s successor Republican William McKinley took office, the Spanish-American war broke out – making Hawaii suddenly enormously valuable to the war effort as a vital refueling station between North America and Asia. Hawaii was quickly annexed by a joint resolution of Congress — not a vote — in 1898.

U.S. President Grover Cleveland

Upon hearing that news, Cleveland, who had retired to Princeton, New Jersey, spoke eloquently for those who had opposed annexation. “Hawaii is ours….as I contemplate the means used to complete the outrage, I am ashamed of the whole affair.”

With those words, Cleveland came to be revered by Hawaiians, some of whom continue to mourn the loss of their nation to this day. Indeed, to this day, Cleveland’s gravestone in Princeton is festooned with shell and flower lei in honor of the stance he took. My friend and colleague Silvia Ascarelli, who I know from our days together in the London bureau of the Wall Street Journal, took this photo and several others and sent them to me.

President Grover Cleveland’s headstone in Princeton, New Jersey, festooned with lei, courtesy of Silvia Ascarelli

The family tradition, it seems, is continuing. The Star-Advertiser reports that reports that George Cleveland has been working closely with Hawai‘i’s Pacific Justice & Reconciliation Center’s Cleveland-Lili‘uokalani Education Project. According to the Associated Press, which distributed the Star-Advertiser’s story, “(George Cleveland) says he’s occasionally the target of criticism for his partnership with the center but he believes there is some kind reparation due for the overthrow.”

I wish I could attend today’s re-enactment, but I was lucky enough to be in Honolulu during one of these gatherings two years ago. The walking tour was fascinating, but best of all was the opportunity to engage with University of Hawaii professors as well as a staffer from the Mission Houses Museum and others on a moment in history that continues to puzzle, anger, and grip so many people.

Mai Poina is co-sponsored by the Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities and the University of Hawai‘i’s Center for Biographical Research. It covers the four days in January 1893, leading up to the overthrow of the sovereign kingdom of Hawai‘i. By moving from station to station on the palace grounds, the tour covers many of the places where the overthrow occurred.

On the year I took the tour, the Center for Biographical Research’s director Craig Howes, dressed in period costume, playing the role of a Greek businessman commenting on the tense political environment. His scene took place at King Kalākaua’s Coronation Pavilion on the palace grounds. One of my favorite memories of that evening was of Craig delivering his lines at dusk on the steps of the pavilion, It turns out he’s an amateur actor in his spare time, and was very good in his role!

Craig Howes in period dress

August 21, 2012

“The Wave” by Susan Casey

The ancient Polynesians felt profound respect for the power of the sea. Their custom was to carry ti leafs with them when they went on risky journeys. As Susan Casey reports in her masterful book, The Wave, California-born but Hawaii-bred surfing legend Laird Hamilton, perhaps superstitiously, always carries a ti leaf along with him as he hunts down the world’s monster waves. “You take the leaf out,” Hamilton told her, “and the leaf brings you home.” And so far it’s worked for him.

The Wave is one of the most suspenseful and fascinating works of narrative nonfiction that I’ve read in a long time. Casey, whose first bestseller was about Great White Sharks, weaves together three different story lines to explore what she calls “the freaks, rogues, and giants of the oceans.” She visits the scientists who are tracking and trying to predict and understand these giants. She spends time with world-class surfers and windsurfers like Laird Hamilton, Darrick Doerner, Brett Lickle, and Dave Kalama – penetrating an extreme subculture to the point of being invited by Hamilton to surf the giant wave off of Haiku on Maui’s north shore, known as Pe’ahi or “Jaws” with him on a Jet Ski. And she also seeks out the mariners – the ship captains and crewmen aboard ships – that have come face-to-face with these terrifying, killer waves.

Part of the pleasure for me in reading “The Wave” was that Casey spent much of her time reporting on the north shore of Maui, a place I’ve visited several times over the past year. Here’s her marvelous description of the former sugar plantation town of Paia, where

“…someone had affixed another sign: “Please Don’t Feed the Hippies.” The edict was delightfully impossible to obey, as everyone in Paia had a touch of hippie soul; it was only a matter of degree. No one cared about your resume in Paia, or that you hadn’t brushed your hair all the way through, or that your truck had seen better days. In the town’s hub, a ramshackle grocery store called Mana Foods, yoga instructors shopped alongside heavily pierced drifters, and pot farmers mingled with supermodels, and Brazilian kitesurfers lined up at the deli counter behind Buddhist priests, and three-hundred-pound Samoan construction workers jostled in the aisles with movie stars…”

There are many such nuggets in “The Wave” and she’s equally gifted at describing places and people. But the emotional heart of her book for me, was her nuanced profile of Laird Hamilton, and his tight team of surfers from Maui’s North Shore who have each other’s backs. Here’s her description of Hamilton’s genius as a surfer:

“Not only did he ride waves that others considered unrideable, at Jaws and elsewhere, but he did it with a trademark intensity, positioning himself deeper in the pit, carving bottom turns that would cause a lesser set of legs to crumple, rocketing up and down the face, and playing chicken with the lip as it hovered overhead, poised to release a hundred thousand tons of angry water. He seemed to know exactly what the ocean was going to do, and to stay a split second ahead of it.”

Laird Hamilton

Casey propelled me through her narrative, including the sections on wave science and the math and physics behind it. But the risks that Casey’s characters were taking was the book’s jet fuel. Would Laird (called Larry by his friends) find a bigger wave? Who would die? Who would get crushed by the insane power and unpredictability of these waves? As someone who studies narrative nonfiction, I was struck by Casey’s skill at making me care about the stakes involved – not just human lives, but the far larger picture of a period of rising seas and steadily bigger waves as a result of climate change.

There are other reasons why I this book captured my imagination. There’s a power in Hawaii that I’ve come to sense – and fear –more and more each time I’ve visited. On my recent stay in Hana on Maui’s windward side, I came away with renewed respect and terror for the ocean. We’d brushed against it ever so slightly, after paddling sea kayaks from Hana Bay to Red Sand Beach in heavy surf. It’s not often that I truly get scared, but that’s what I felt when faced with swells approaching perhaps ten or twelve feet

Consider, then, the rush of adrenalin and fear that accompanies fifty-foot waves – or a hundred foot monsters – or even a hundred and twenty foot behemoths. Then, take one imaginative step further and join writer Susan Casey in not only tracking down the big-wave surfers who hunt down these terrifying beasts on Jet-Skis in California, Mexico, South Africa, and Hawaii – but even has the courage to join them out on those seas (most terrifyingly, on the back of Laird Hamilton’s Jet Ski as he confronts Jaws.)

Did I love this book so much because I’m afraid of the ocean and, thus, found it fascinating to read about people who overcome their fear? That could help partly explain it. In terms of Casey’s ability to talk to such a wide range of people and truly be invited into their worlds, as a reporter, I admire what she did. I’d love to meet her myself some day and ask her more about how she reported this book. But the very best part of The Wave for me was at the very end, as a typhoon approached Maui’s north shore in late 2009 and Hamilton flies from his home on Kaui to ride his board, the Green Meanie, on Jaws. I won’t spoil the suspense by telling you what happens, but it’s beautiful.

A footnote: Casey’s book has inspired me to take a tiny first step of my own towards not fearing the ocean so much. Our local community college has a course called “Surfing 101,” which takes place out at Stinson Beach, just north of San Francisco. I’m signing up for it today but am wondering – can I find a ti leaf to carry with me?

August 12, 2012

Susan Orlean on Stagecraft (and How Writing Can Be Like Stripping…)

I just spent the past few days as a faculty member of the 21st Annual Book Passage Travel Writers & Photographers Conference. I was on a panel with Andrew McCarthy, who made his name as an actor in “Pretty in Pink,” “St. Elmo’s Fire,” and “Less Than Zero,” and is now an award-winning travel writer for National Geographic Traveler and elsewhere. It was also a treat to discuss the “Art of Attention” on a panel with veteran travel writers David Farley, Larry Habegger, and Georgia Hesse.

But the real thrill for me was the chance to meet the author and New Yorker writer Susan Orlean, who was just as delightful in person as she is in her books such as The Orchid Thief (which became the movie Adaptation, starring Meryl Streep playing her,) The Bullfighter Checks Her Makeup, and My Kind of Place. In introducing Susan, Book Passage President Elaine Petrocelli noted that when a New Yorker arrived at her home with a new story by Susan in it, her husband Bill knew to leave her in peace until she’d finished it.

Author and New Yorker staff writer Susan Orlean, who was the keynote speaker for the 21st annual Book Passage Travel Writers & Photographers Conference

I feel the same way. These days, I read the New Yorker on my ipad and when there’s a new story by Susan Orlean, I’ll read it first thing (though a close second is anything by David Grann, who wrote The Lost City of Z and a remarkable recent piece about an American who took part in the Cuban revolution entitled “The Yankee Commandante.”) Susan has a gift for looking at something seemingly ordinary – a supermarket in Queens, N.Y., for example – and carrying her along with us as she discovers deeper truths through it.

With lovely ginger hair and a playful floral skirt, Susan told a packed audience of more than a hundred people last night that she starts her stories with authentic curiosity about her subject. She found herself landing in the baking oil town of Midland, Texas, at one point with no idea at first how to understand it. But her questions drove her: why would people settle in a town where the air seemed “dry-roasted” and the earth was so hard that gravediggers needed jackhammers to bury a casket? What would the town reveal about George W. Bush, who once said in an interview that if people “want to understand me, (they) need to understand Midland…”? So Susan, pursuing the answer to that question, flew to Midland in an experience she called “sort of an emotional Outward Bound” — choosing to arrive unprepared so as to remain open to the place, yet as a result feeling “panic, despair, and existential loneliness.”

It all worked out in the end, as a man she met in a coffee shop took her under his wing and became her guide to Midland for the next three days. (Click here to read her story, “A Place Called Midland.”) Reluctant to begin an encounter with someone by taking notes, she prefers to observe and listen carefully. “What’s important is paying attention.” As for using a tape recorder, she’s not a fan, noting that they can’t capture the texture of a place or the emotions behind someone’s words.

Curiosity isn’t enough, of course, And Susan employs what she calls “stagecraft” – the art of performance, as the writer unfolds and paces a story, controlling the highs and the lows, and building in suspense and surprises. Had she not become a writer, “I think my other career path would have been as a stripper,” she joked to Don George, the conference’s self-described “Papa” and founder in conversation with her last night. Her point was that a successful storyteller – like a skilled stripper –slowly reveals the story’s surprises, rather than ripping all her clothes off at once and standing there naked. The pleasure is in the control. (The image of Susan pole dancing somehow came up in the conversation – delightfully making Don lose his train of thought and his cheeks turn pink!)

Susan Orlean and Don George in conversation on August 11, 2012

Someone in the audience asked Susan what she meant by stagecraft. “I think writing is performance,” she said, “and it is important to imagine it being performed.” She went on to explain that the experience of reading is a rhythmic and paced experience and she shared advice that I used throughout the many drafts of my latest book, Lost Kingdom: “The Number one thing you should do with your writing is to read it out loud.” Very, very good advice, as often you can’t spot problems in the language or the rhythm purely by looking at words on a screen or a page. You have to listen.

How do you start your stories, another person asked her. Often, an image or a phrase comes to mind. In the case of her story on Midland, Texas, the idea began with George Bush’s quote about understanding him through understanding the town. Then, for Susan, it was the image of needing a jackhammer to get buried that stuck with her. It seemed like a place that people really shouldn’t live in – but did, because of the promise of getting rich from oil there. In her latest book, Rin Tin Tin, which I’ve just started, it was the word “immortality” that stuck – the way that this iconic German Shepherd, who’s been dead for more than half a century, still lives through film, books, and other images.

After her talk, Susan’s fans waited in a long line to get their books signed. When she finished that, the conference folks surrounded her, eager to hear more about the affair she’d had with a guide in Bhutan during an earlier panel called “Lust in Translation” (she was in the audience, but had been asked, at one point, to share her experiences.) My author friends Allison Hoover Bartlett, who wrote The Man Who Loved Books Too Much, and Cara Black, who writes the Aimee LeDuc investigation series, as well as our physician writer friend Katherine Neilan, all made the trek from San Francisco to hear Susan. And, despite San Francisco Chronicle travel editor Spud Hilton‘s best efforts to corral us into karaoke, it was too late to stay. Still, we all agreed it was well worth it – with many thanks to Book Passage, Don George, and everyone who made this wonderful conference possible.

August 10, 2012

How an 1863 petition from Ni’ihau re-surfaced in San Francisco

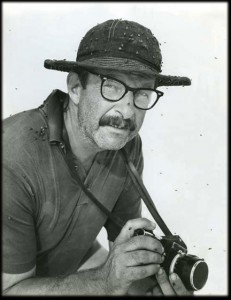

The story begins in November of 1957. The chief photographer for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Warren Roll, climbed into the passenger seat of a small plane in Kauai. The pilot took off, heading towards a 73-square-mile privately-owned Hawaiian island of Niihau.

The plane landed roughly, smashing its landing gear and splintering its propeller. Roll, carrying his camera gear, left the pilot and set off across the island in search of the island’s one village. The Robinson family, who by that time had owned the island for nearly a century, had restricted access to it for decades. Roll, an unusually enterprising photojournalist, had successfully penetrated what was by then known as the “Forbidden Island.”

The late Warren Roll in a photo taken on Midway Island, courtesy of Jonah Roll

Hot, thirsty, and exhausted after walking for hours, Roll finally reached the village. He called out to the first people he saw, “Hello! Will you help me?” And they did. In a pattern that began with the arrival of Captain James Cook, the British explorer who was the first westerner to reach this archipelago of volcanic islands long-isolated in the north Pacific in 1778, the Native Hawaiians of Niihau (pronounced Nee-ee-how) warmly welcomed Roll, who, like Cook, was a “haole” or foreigner to them.

Roll then took a series of photographs for his newspaper of the Native Hawaiians who lived on the island which were published in a two-page spread in the Star-Bulletin on November 16, 1957. Its headline was “Free Though Feudal. They’re Happy on Niihau: Iron Curtain Lifted For the First Time. Much of What You Hear About the Island Isn’t So.” His scoop caused a sensation.

Warren Roll’s “crash” landing on Niihau in 1957, courtesy of Jonah Rolls

But what Roll didn’t reveal in the story how he also ended up with a crumbling, hand-written petition on bluish lined parchment paper with 105 signatures on it that remained buried in his files for years. Whether he was given the petition during that first trip, or somehow acquired it on another occasion, is not clear. But the recent discovery of this 1863 document underscores the sometimes surprising ties between the Hawaiian islands and San Francisco.

Warren Roll eventually retired from the Star-Bulletin and returned to the mainland. He died in 2008. The bulk of his archives, which included negatives from his decades of work on the islands as well as materials he collected for a possible book on Niihau, ended up in a small, wooden toy box with one of his sons, the fine arts painter Jonah Rolls. Jonah lives with his wife and two daughters in Project Artaud, an arts colony on the industrial edge of San Francisco’s Mission District.

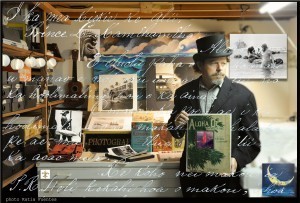

Artist Jonah Roll in his studio in Project Artaud, San Francisco. Photograph by Katia Fuentes.

Jonah, who was born in the islands and raised aboard a 38-foot ketch named the Flying Walrus in Honolulu’s Ala Wai boat harbor, had begun having bad dreams about his father’s archives and worried that something would happen to them. “I love having it here, but it’s slowly taking its toll,” the painter said, noting the mana or power of the island of Niihau and the burden he felt keeping his father’s archives safe.

I first met Jonah after a longtime staff cameraman at KQED, Harry Betancourt, approached me in the green room after I’d been on Michael Krasny’s Forum show to talk about my book on Hawaii, Lost Kingdom. Harry suggested I reach out to Jonah, who had inherited some interesting materials on the islands from his father. I visited Jonah and his family and their home in Project Artaud twice, and Jonah ended up asking me to get in touch with the head of the Hawaii State Archives to translate the document from the Hawaiian into English and also to put it into its historical context. Within a day, Jonah had the translation.

Jonah had long suspected the document had something to do with the purchase of the island. Indeed, in early 1864, the Robinson family had bought the island for $10,000 in gold from Hawaii’s King, who had found it somewhat troublesome to own and thus wanted to sell. Located 17 miles off the coast of Kauai, Niihau suffered from regular droughts. What’s more, the king had some difficulties collecting rents from the Hawaiian tenants. The Robinsons, which had come to the islands from Scotland after a long stopover in New Zealand, moved to Niihau with the plan of raising cattle and sheep.

Early in the 20th century, when Hawaii was still an American territory and the archipelago had not yet become the 50th state, the Robinsons decided to restrict access to the island only to those already living there – mainly a few hundred Native Hawaiians. Outsiders could only visit with the family’s permission.

As the decades passed and the Hawaiian language was actively suppressed by the territorial government, Niihau became the only place in the world where Hawaiian was the predominant language spoken. Legends and myths sprung up about the island, which is the geologically oldest of the seven inhabited Hawaiian Islands, and also said to be the birthplace of the volcano Goddess, Pele.

Roll, who had served in as an aerial photographer for the Navy during WWII and the Korean War had the knack for being in the right place at the right time and he wanted to see the place for himself. His son Jonah believes he intended to land there in search of a journalistic coup. (Click here to see some of Warren’s photographs.)

Long after that crash and trek in 1957, the memory of what Warren Roll saw on Niihau stayed with him. “He became completely obsessed,” his son Jonah recalls. He began collecting documents, newspaper clippings, and other materials – some of which ended up in what he called his “Unauthorized Niihau Scrap Book.” Upon retiring from the paper, he shipped a file cabinet with him to the mainland. It included background on the Robinson family and, according to Jonah, at one point had contact with an estranged member of the Robinson family about what he’d found. The crown jewel of his collection was the document in Hawaiian from 1863.

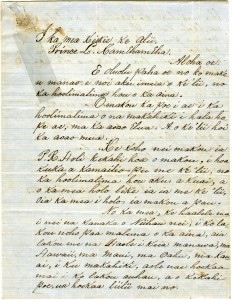

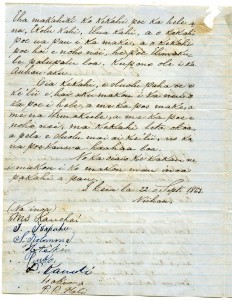

A petition from residents of Niihau dated 1863, first page. Courtesy of Jonah Roll.

Click here for a translation of the 1863 Niihau Petition

A petition by the residents of Niihau, dated 1863 — page 2. Courtesy of Jonah Roll.

After getting the translation done by a staffer at the Hawaii State Archives, Jonah became even more concerned about the burden of taking care of it. It turned out to be a petition from virtually every single resident of the island at the time asking the King for a new lease of the island to the island. The petition came at the time that the Robinsons were negotiating to buy it from the king. Although there are similar letters between the island’s residents and the Minister of the Interior, the archive did not have this one — and there is no mention in the standard histories of nineteenth century Hawaii of an attempt by the native Hawaiian residents to maintain their grip on the island (with the exception of a fragment of this letter in an appendix to a book about Ni’ihau published in 1989.)

The ending to the story? Jonah Roll has offered to donate the petition to the Hawaii State Archives, sending it back to the islands along with his father’s photo archive. As for the mystery of how this document ended up in an artist’s studio in San Francisco, it’ll probably never be solved. “I can only wonder where the letter came from,” he says. “But I want to get it back to Hawaii, where it belongs.”

August 7, 2012

Mondavi and Backen: Napa’s First Family and its Favorite Architect

An invitation landed in my inbox recently with the subject heading: “Mondavi and Backen.”

Reading a bit further, I learned that the Peter Mondavi family, owners of Charles Krug, had hired the famed Napa Valley-based architect, Howard Backen, to help it rebuild their winery. I was invited to the groundbreaking celebration today for the $6 million refurbishment of a grand old Redwood Cellar.

I’d first visited this 1872 building about eight years ago, as I began reporting the Wall Street Journal story on the Mondavi family that would eventually become “The House of Mondavi.”

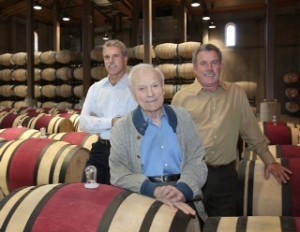

Peter Jr., Peter Sr., and Marc Mondavi at the Charles Krug Winery. Photo by Duncan Garrett.

My memory of it then was a decrepit wooden pile laced with cobwebs.. The family had stored boxes of ancient files, furniture, and toys dating back decades on the cellar’s third floor. It was clear from the state of this creaky old structure that the Peter Mondavi side of the family had not invested in its winery in the way that the Robert Mondavi had since the famous family bust-up in 1966.

On my tour, I was more interested in the file cabinets and papers that were gathering dust on its third floor – I remember hoping that I might someday have a chance to look through them (I never did, though that branch of the family did help me with my book, as did Robert’s side of the family.)

Nowadays, the cobwebs, boxes, and even the catwalks where the Mondavi boys would shoot spitballs at unsuspecting visitors walking below are nowhere to be found as the family’s latest 14-month construction project begins. The old-fashioned sign beckoning visitors off Highway 29 has disappeared and been replaced by a new one. In recent years, the Peter Mondavi family has replanted many of its 850 acres of prime Napa Valley land in Bordeaux varietals.

“It’s been a long road…with up and downs,” said Peter Sr., holding a glass of white wine in the mid-day sun. “But it’s been great.” (For a sweet and humorous glimpse of the patriarch of his branch of the family, watch this video of 97-year-old patriarch climbing the steps to work every day.)

Howard Backen listened as Peter spoke at the groundbreaking about his parents, Cesare and Rosa, who started the family business. “You have to give them the credit,” Peter said. They were both hard workers and, based on what I know about Howard Backen after profiling him for the Wall Street Journal last year, I’d bet he’d be working just as hard as he always has thing when he reaches Peter Sr.’s age. Backen has designed projects for the late Steve Jobs and the vintner Bill Harlan, as well as three branches of the Mondavi family.

Backen noted that the Mondavi family has not made peace with each other as a whole. At today’s groundbreaking, for instance, none of the members of Robert’s side of the family attended as far as I could tell. But as a whole, the Mondavis haven’t been letting any dust settle over it in recent years, as they continue to make wine and appreciate the good life.

On August 26 Robert Mondavi’s widow Margrit will be signing copies of her new book, “Margrit Mondavi’s Sketchbook: Reflections on Wine, Food, Art, Family, Romance and Life.” She’s donating the proceeds to one of the many non-profits that she and her husband supported over the years, the Oxbow School. Howard Backen is working with her to design her new home.

Timothy Mondavi, meanwhile, was the subject of a cover story in Wine Spectator magazine last November by senior writer James Laube, who’s been one of the most astute chroniclers of the Mondavi family’s fortunes over the years. With his sister Marcia and other family members, he’s making Continuum, a $150 a bottle red blend that has won high praise from Laube, Robert Parker, and other wine critics. Howard designed the Continuum winery, which is now being built.

And what about Michael? He’s still running Folio Fine Wine Partners with his son Rob and his daughter Dina, which imports such well-known Italian brands as Marchesi de Frescobaldi as well as produces its own wine under its own label, such as M by Michael Mondavi. His family is the only one not to use Howard or his firm as their architect

Backen and his wife and daughter have started their own new family business recently: a restaurant in St. Helena called French Blue. My son and I stopped there for lunch after the groundbreaking. I loved the Parker House rolls and the Grilled Chicken Paillard salad with peppery greens, crispy shallots, and soft-boiled farm eggs.

But the most memorable part of the meal was the starter that my adventurous 14-year-old convinced us to try: Fried Pig’s Ears with a chili lime and garlic dip. As we waited for them to arrive, I asked him whether he thought they’d taste like potato chips. “They’re meat, Mom!” he replied.

Fried Pigs’ Ears from French Blue in St. Helena

August 2, 2012

Veering Off the Hana Highway

My family and I just returned from a week in Hana, on the eastern coast of Maui. The town is probably best known for the road leading to it –a series of heart-stopping one-lane bridges and sheer vertical drops to the ocean below. But tourists who drive to Hana and back in a day from resorts on the sunnier side of this Hawaiian island miss exploring one of the most isolated and beautiful spots on earth.

Sunset at Hale Honu

We stayed at a home owned by descendants of Claus Spreckels, a nineteenth century businessman who became known as the “sugar king” of Hawaii and a central character in my recent book, Lost Kingdom. Known as Hale Honu (Turtle House,) it overlooks the sea and is located just down the street from the Hana Cultural Center. One of the smaller bedrooms of the house contains the restored wooden bed of the burly sugar baron himself. Each night, we went to sleep to the sounds of the pounding Pacific. In the morning, we ate breakfast on the deck, looking out at the ocean and at the gracious lawns.

Below the house was a natural lava tub: at low tide, all four of us could sit in the protected pool, enjoying the seawater but sheltered from the powerful swells. We learned very quickly to wear our wetsuit booties on the sharp lava rock when we climbed down to the tub or explored the tide pools.

A family swim in the natural lava pool at Hale Honu.

With two energetic teenage boys, we reached out to a local, Shawn Spillett, who runs a company called Hana Productions and manages the local ranch of the famed photographer David LaChapelle, to take us to places that tourists generally never find. Our first day, we kayaked from Hana Bay, around a rocky peninsula, to Kaihalulu, the famous red sand beach. It was a windy day and the waves topped ten feet. Paddling through those swells and then navigating our ocean kayaks through a narrow channel, with dangerous rocks on either side, proved thrilling but also a bit terrifying. At one point, a big swell directly broke over Shawn’s kayak, punching him in the face as he turned to make sure the two kayaks that my husband Charlie and I and our sons Cody and Andrew, were on course.

Since we’d cheated fate by managing to avoid capsizing our kayaks, Shawn wisely decided we should hike out of the beach instead. (He came back later with his crew to paddle the kayaks back at sunset, when the seas had calmed down quite a bit.) That afternoon we hiked several miles across lava to Wai’anapanapa State Park, where we dove into a fresh water pool leading to a wonderfully watery cavern. Afterwards, Shawn gave us a tour of his quirky garden and greenhouse. Shawn’s bride Rachel, after hearing about our day, quipped, “Shawn tends to push people’s limits.” Yes he did – and we loved every minute of it!

A playful planter in Shawn's greenhouse...

The highlight of the second day was the four mile Pipiwai Trail in the Haleakala National Park leading through an eerie bamboo forest to the Waimoku Falls — with a 400-foot vertical drop down sheer lava rock. Then we looped around above the O’heo Gulch (or the seven sacred pools) following a back trail to Kapahu Living Farm, a taro farm tended by a Hawaiian kapuna (elder) named Uncle John, who invited us to enjoy some coconuts from the trees. Shawn cut them down for us and we ate the fresh coconut meat and drank the milk. Afterwards, we hiked down to the tourist-packed waters of the seven sacred pools – probably our least favorite part of the trip.

Afterwards, we ate salad at the Laulima organic farm in Kipahulu, where the young mother who picked the lettuce explained (since she couldn’t offer us forks) that eating the salad with our hands provided more mana (life-force or power.) Eating salad with our hands was something new for all of us. Although we were sad that the farm no longer offered its famous bicycle-powered smoothies, we walked though the farm afterwards, most memorably through resting fields planted with spearmint (with its sharply delicious fragrance releasing as our footsteps crushed the plants’ leaves.) Then Shawn led us through the remains of an old sugar mill, mostly buried already beneath the area’s verdant plant life, and finally to the achingly lovely grounds of the Palapala Ho’omau Church In Kipahulu to see the gravestone of the aviator Charles Lindbergh, who died in Maui in 1974.

Day Three we hiked from Waioka, where we all dove from cliffs into what locals call the Venus Pool, to Hamoa Beach, made famous by James Michener, who praised it as being the most “South Pacific” beach in the North Pacific. We loved it and stayed there until dusk, since Shawn had brought a surfboard, stand-up paddleboard (SUP) and a skim-board for the boys to try. Charlie stayed in the longest, simply floating on a boogie board as a short cloudburst came and brought with it a rainbow.

Cliff diving into Venus Pool

After such a heavenly afternoon, my husband Charlie and I headed to the Travasaa Hotel Hana (long known as the Hotel Hana Maui) to hear local Leokane Pryor, a falsetto singer with roots in nearby Kipahulu who’s released two albums on the Mountain Apple label. At the bar, Shawn introduced us to Lee-Ann Kahookele-Paman, who sang on two tracks of Leokane’s most recent album, Home Malanai, and who told me that her Hawaiian family could trace its roots through the Kumulipo, the Hawaiian chant translated in 1897 by Hawaii’s last queen, Lili’uokalani, that some scholars have compared to the Greek creation myths and Hebrew genesis. Lee-Ann also brought me up to date on the recent news of the Hawaiian Registry Program, an effort by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs to provide Hawaiians worldwide with a card verifying their Hawaiian ancestry.

We headed back to Hamoa beach the next morning (just a 10 minute drive from the house) and that afternoon, embarked on our final, epic adventure. At mid-day, after lunch, we headed north from the house to the Wailua Valley, following the original and overgrown Hana highway past aquaducts, inching along sheer cliffs, and eating wild guava and passion fruit along the trail. It lightly rained much of the time, as we headed into dense cloud-forest where hunters track down boar. We saw wild orchids, native Koa trees, massive red eucalyptus covered with spongy green moss, and unusual ferns as we mucked our way through a lot of mud. As our 16-year-old Cody said, it was “60% hike, 40% swim.”

We hiked several miles away from the Hana Highway into one of the most remote valleys in the islands, plush with ferns and wild ginger whose blossoms tasted like honeysuckle. We felt exhilarated at the end of the long day (Shawn said we hiked 6 miles or so — but it seemed like a lot more.) We ended up in Keanae, at the arboretum there, and Shawn hitchhiked back to where we’d left the car. The sun went down and near the entrance of the spooky arboretum: a car had tumbled over the edge into a ravine perhaps years ago and was now slowly being absorbed by the jungle. It felt a little like a Twilight Zone episode but even so, a strange and wonderful end to a great day.

Our friend and fearless leader, Shawn Spillett of Hana Productions

After Hana, the town of Paia was a bit of a disappointment. We enjoyed our dinner at Mama’s Fish House, though it was very pricey – especially the fact that the restaurant named the fisherman who caught that evening’s fish. (I ordered the “Ono caught trolling along the north shore of Maui by Jeff Holland” – I kid you not – and my husband. Charlie had the “Opah caught in local waters aboard the fishing vessel “Vak 2” by Jonathan Ganados.” Both were delicious.

But nothing rivaled the mahi-mahi in a vegan curry sauce prepared by the talented Robin Newton, a renowned island chef and caterer, for us the first night we arrived – the fish caught the previous day by her husband Brad, not all that far from the Hana Bay and the wonderful Hale Honu.

The Siler family in Hana, Cody, Charlie, Julie, and Andrew

Julia Flynn Siler is the bestselling author of “Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure,” published by the Atlantic Monthly Press. For more information, please visit www.juliaflynnsiler.com

March 15, 2012

Lunching with One of Hawaii’s Real ‘Descendants’

Julia Flynn Siler and Her Royal Highness Princess Abigail Kawananakoa.

A few days before heading to Honolulu on book tour for “Lost Kingdom,” I got a phone call from the assistant to Her Royal Highness Princess Abigail Kawananakoa, the woman who is the most direct descendant of the last queen of Hawaii. If the monarchy had not been overthrown in 1893, Princess Abigail today might well have become Hawaii’s queen.

I’d interviewed Princess Abigail by phone for a page one story I’d written last year for the Wall Street Journal. The story was about how the Friends of Iolani Palace, a group of volunteers founded by Princess Abigail’s mother, had been on a decades-long search to recover lost furniture and artifacts that disappeared in the months and years after a small group of businessmen deposed Queen Liliuokalani at the end of the nineteenth century.

While I’d visited Iolani Palace many times in the course of researching Lost Kingdom (the palace is on the same grounds as the Hawaii State Archives) I had not met Princess Abigail. Known by her Hawaiian name “Kekau” (pronounced kay-kow) the Princess is in her eighties and divides her time between homes in Honolulu and California. The last time a journalist had interviewed or spent any time with the Princess was for a Life magazine profile of her in 1998.

I was thrilled – and also a little terrified – when her longtime assistant, Maggi Parker, invited me to join the Princess for lunch at the Mariposa, the restaurant in the Nieman Marcus at Honolulu’s Ala Moana shopping center. What would I wear? What gifts should I bring? How should I address her? I wasn’t such a hard-bitten reporter that I didn’t fret over the etiquette required – even though our luncheon was taking place not at a palace, but at an all-American shopping mall.

I chose a conservative light -grey pants suit, which turned out to be a good pick for the occasion. I’d raced to a nearby stationery store before the lunch to buy a bright orange gift bag and pink tissue to wrap a bottle of Robert Mondavi cabernet I’d brought her from California, as well as a signed copy of my first book, “The House of Mondavi.”

As I rode the escalator up several floors to the restaurant, past hundreds of gold-colored butterflies suspended from the ceiling, I was damp with perspiration and worried I’d be late. As it turned out, I arrived before almost everyone else. The table was still being decorated with cuttings of delicate black-stemmed ferns – Queen’s Ferns, as it turned out — from a guest’s garden, along with fuschia-colored orchid lei.

We sipped on blood-orange spritzers as we waited for the Princess’s chauffeur, driving her deep blue Rolls Royce, to drop her off. When she arrived, a ripple of excitement passed through the restaurant, as the manager and staff made a fuss over her, escorting an elegant octogenarian with carefully coiffed blonde hair who was wearing a flowing, cream and white silk pants suit to our long table. We sat with our backs to the wall where a large mural portrayed of hula dancers in grass skirts were dancing on a beach behind us. (The Princess later commented that the dancers didn’t look particularly Hawaiian to her.) Our view through the Mariposa’s windows was of the vast Pacific.

Fox Searchlight

George Clooney as Matt King and Shailene Woodley as Alexandra in “The Descendants.”

The occasion, as it turned out, was a celebration of her assistant Maggi’s birthday, which she had modestly forgotten to mention to me on the phone. Luckily, I’d brought her a small gift too. But Maggi had very kindly seated me next to the Princess, where I had the treat of hearing about her days as a boarder at Notre Dame High School in Belmont, Ca., a Catholic girls’ school outside of San Francisco.

The Princess was not entirely pleased by the service at the Mariposa: more than once, she extended her index finger at the overworked waitress, arched her eyebrows, and commanded her to bring drinks and menus to the table right now! I was secretly pleased to see that the Princess acted like, well, a princess. Later, Maggi explained to me that the Princess typically demanded excellent service and, in turn, was known for tipping generously.

Before the slices of Valharona chocolate cake arrived, Maggi’s friend Ann McCormack gave us a nice surprise. In the 1950s and 1960s, Ann had sung in the Honolulu nightclub that she had owned with her husband and toured with Frank Sinatra as his opening act in Las Vegas and elsewhere. At lunch, she sang a special birthday song for her long-time friend.

Ann and Maggi also swapped stories of appearing in small roles in the original “Hawaii Five-0″ and the movie “Hawaii,” based on James Michener’s 1959 novel. Ann and Maggi, it seems, were quite the girls-about-town in Honolulu during the 1950s and 60s. The funniest story involved Maggie once appearing onstage at the nightclub wearing a Playboy bunny’s outfit as a gag, and they reminisced over the filming of Hawaii, including one of the scenes shot at the Princess’s Honolulu home.

What a treat for me – and a big mahalo (thank you in Hawaiian) to Maggi for including me at such a lovely luncheon. After having spent the past four years digging through archives to write a book about the Princess’s family (she is the great-grand niece of King David Kalakaua and Queen Kapi’olani.) I was deeply honored by their interest in my book.

I couldn’t resist asking Kekau (yes, she invited me to call her that) whether she’d seen “The Descendants,” the Oscar-nominated movie starring George Clooney which is based on the novel by local writer Kaui Hart Hemmings (It’s out on DVD on March 13). She hadn’t – and while I offered to take her to the movies to see it – she was decidedly cool to the idea. It seemed that she hadn’t been to a commercial movie theater to see a film in a very long time.

To deepen the mystery, however, one of the other guests, Teri Stroud, seated to the other side of the Princess, leaned towards me. In a conspiratorial whisper, explained that the Princess was the real descendant – in other words, the person upon whom the George Clooney character, Matt King, in “The Descendants” was based. In Kaui’s novel, Matt King was descended from Hawaiian royalty on one side and white sugar plantation owners on the other. The Clooney character describes himself as looking like a haole – the Hawaiian word for a foreigner, but generally used to describe a white person – even though he is part-Hawaiian.

Princess Abigail, likewise, does not resemble what some think Hawaiian princess would look like. She told me at lunch that when she first arrived at her boarding school in California, she overheard some girls talking about her and wondering how fat and how dark-skinned she would be – not realizing they were being overheard. For the record, the Princess is light-skinned and slender with blue eyes. Like Matt King, she could easily be mistaken for a haole herself.

And like the Matt King character, Princess Abigail is a member of a powerful family – the Campbells – which held many of their assets in a trust. Princess Abigail played a crucial role in 2007 in deciding what should happen to the Campbell Estate when it ran into a Hawaiian law, the rule against perpetuities, requiring it to wind down twenty years after the last death of the direct descendants who had been alive at the time of the trust’s creation.

The thirty beneficiaries of the trust are descended from James Campbell, an Irishman who immigrated to the islands in the mid-nineteenth century and who built his fortune as a partner in a Maui sugar plantation. According to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, she was the largest beneficiary of the trust and her proceeds from it were close to a quarter of a billion dollars. She has used some of that wealth to help fund the Abigail K. Kawananakoa Foundation to support the preservation of Hawaiian culture.

That said, “The Descendants” author Hart Hemmings told me she’d based her fictional characters on a number of families and family trusts in the news at time she wrote her book – not just the Campbells. Another family that went through similar experiences were the Wilcoxes (whom the author Hart Hemmings is related to) according to friends that I met later in my trip and had drinks with at the Outrigger Canoe Club, one of the settings of Hart Hemmings’ novel. While the novel was based on an amalgam of powerful local families, it was still a great honor to meet Princess Abigail, who was born long before Hawaii became the 50th State and who’d lived through its tumultuous history.

How often, after all, does one have the chance to meet true American royalty?

Julia Flynn Siler is the bestselling author of “Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure,” published by the Atlantic Monthly Press. For more information, please visit www.juliaflynnsiler.com

Lunching with One of Hawaii's Real 'Descendants'

Julia Flynn Siler and Her Royal Highness Princess Abigail Kawananakoa.

A few days before heading to Honolulu on book tour for "Lost Kingdom," I got a phone call from the assistant to Her Royal Highness Princess Abigail Kawananakoa, the woman who is the most direct descendant of the last queen of Hawaii. If the monarchy had not been overthrown in 1893, Princess Abigail today might well have become Hawaii's queen.

I'd interviewed Princess Abigail by phone for a page one story I'd written last year for the Wall Street Journal. The story was about how the Friends of Iolani Palace, a group of volunteers founded by Princess Abigail's mother, had been on a decades-long search to recover lost furniture and artifacts that disappeared in the months and years after a small group of businessmen deposed Queen Liliuokalani at the end of the nineteenth century.

While I'd visited Iolani Palace many times in the course of researching Lost Kingdom (the palace is on the same grounds as the Hawaii State Archives) I had not met Princess Abigail. Known by her Hawaiian name "Kekau" (pronounced kay-kow) the Princess is in her eighties and divides her time between homes in Honolulu and California. The last time a journalist had interviewed or spent any time with the Princess was for a Life magazine profile of her in 1998.

I was thrilled – and also a little terrified – when her longtime assistant, Maggi Parker, invited me to join the Princess for lunch at the Mariposa, the restaurant in the Nieman Marcus at Honolulu's Ala Moana shopping center. What would I wear? What gifts should I bring? How should I address her? I wasn't such a hard-bitten reporter that I didn't fret over the etiquette required – even though our luncheon was taking place not at a palace, but at an all-American shopping mall.

I chose a conservative light -grey pants suit, which turned out to be a good pick for the occasion. I'd raced to a nearby stationary store before the lunch to buy a bright orange gift bag and pink tissue to wrap a bottle of Robert Mondavi cabernet I'd brought her from California, as well as a signed copy of my first book, "The House of Mondavi."

As I rode the escalator up several floors to the restaurant, past hundreds of gold-colored butterflies suspended from the ceiling, I was damp with perspiration and worried I'd be late. As it turned out, I arrived before almost everyone else. The table was still being decorated with cuttings of delicate black-stemmed ferns – Queen's Ferns, as it turned out — from a guest's garden, along with fuschia-colored orchid lei.

We sipped on blood-orange spritzers as we waited for the Princess's chauffeur, driving her deep blue Rolls Royce, to drop her off. When she arrived, a ripple of excitement passed through the restaurant, as the manager and staff made a fuss over her, escorting an elegant octogenarian with carefully coiffed blonde hair who was wearing a flowing, cream and white silk pants suit to our long table. We sat with our backs to the wall where a large mural portrayed of hula dancers in grass skirts were dancing on a beach behind us. (The Princess later commented that the dancers didn't look particularly Hawaiian to her.) Our view through the Mariposa's windows was of the vast Pacific.

Fox Searchlight

George Clooney as Matt King and Shailene Woodley as Alexandra in "The Descendants."

The occasion, as it turned out, was a celebration of her assistant Maggi's birthday, which she had modestly forgotten to mention to me on the phone. Luckily, I'd brought her a small gift too. But Maggi had very kindly seated me next to the Princess, where I had the treat of hearing about her days as a boarder at Notre Dame High School in Belmont, Ca., a Catholic girls' school outside of San Francisco.

The Princess was not entirely pleased by the service at the Mariposa: more than once, she extended her index finger at the overworked waitress, arched her eyebrows, and commanded her to bring drinks and menus to the table right now! I was secretly pleased to see that the Princess acted like, well, a princess. Later, Maggi explained to me that the Princess typically demanded excellent service and, in turn, was known for tipping generously.

Before the slices of Valharona chocolate cake arrived, Maggi's friend Ann McCormack gave us a nice surprise. In the 1950s and 1960s, Ann had sung in the Honolulu nightclub that she had owned with her husband and toured with Frank Sinatra as his opening act in Las Vegas and elsewhere. At lunch, she sang a special birthday song for her long-time friend.

Ann and Maggi also swapped stories of appearing in small roles in the original "Hawaii Five-0″ and the movie "Hawaii," based on James Michener's 1959 novel. Ann and Maggi, it seems, were quite the girls-about-town in Honolulu during the 1950s and 60s. The funniest story involved Maggie once appearing onstage at the nightclub wearing a Playboy bunny's outfit as a gag, and they reminisced over the filming of Hawaii, including one of the scenes shot at the Princess's Honolulu home.

What a treat for me – and a big mahalo (thank you in Hawaiian) to Maggi for including me at such a lovely luncheon. After having spent the past four years digging through archives to write a book about the Princess's family (she is the great-grand niece of King David Kalakaua and Queen Kapi'olani.) I was deeply honored by their interest in my book.

I couldn't resist asking Kekau (yes, she invited me to call her that) whether she'd seen "The Descendants," the Oscar-nominated movie starring George Clooney which is based on the novel by local writer Kaui Hart Hemmings (It's out on DVD on March 13). She hadn't – and while I offered to take her to the movies to see it – she was decidedly cool to the idea. It seemed that she hadn't been to a commercial movie theater to see a film in a very long time.

To deepen the mystery, however, one of the other guests, Teri Stroud, seated to the other side of the Princess, leaned towards me. In a conspiratorial whisper, explained that the Princess was the real descendant – in other words, the person upon whom the George Clooney character, Matt King, in "The Descendants" was based. In Kaui's novel, Matt King was descended from Hawaiian royalty on one side and white sugar plantation owners on the other. The Clooney character describes himself as looking like a haole – the Hawaiian word for a foreigner, but generally used to describe a white person – even though he is part-Hawaiian.

Princess Abigail, likewise, does not resemble what some think Hawaiian princess would look like. She told me at lunch that when she first arrived at her boarding school in California, she overheard some girls talking about her and wondering how fat and how dark-skinned she would be – not realizing they were being overheard. For the record, the Princess is light-skinned and slender with blue eyes. Like Matt King, she could easily be mistaken for a haole herself.

And like the Matt King character, Princess Abigail is a member of a powerful family – the Campbells – which held many of their assets in a trust. Princess Abigail played a crucial role in 2007 in deciding what should happen to the Campbell Estate when it ran into a Hawaiian law, the rule against perpetuities, requiring it to wind down twenty years after the last death of the direct descendants who had been alive at the time of the trust's creation.

The thirty beneficiaries of the trust are descended from James Campbell, an Irishman who immigrated to the islands in the mid-nineteenth century and who built his fortune as a partner in a Maui sugar plantation. According to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, she was the largest beneficiary of the trust and her proceeds from it were close to a quarter of a billion dollars. She has used some of that wealth to help fund the Abigail K. Kawananakoa Foundation to support the preservation of Hawaiian culture.

That said, "The Descendants" author Hart Hemmings told me she'd based her fictional characters on a number of families and family trusts in the news at time she wrote her book – not just the Campbells. Another family that went through similar experiences were the Wilcoxes (whom the author Hart Hemmings is related to) according to friends that I met later in my trip and had drinks with at the Outrigger Canoe Club, one of the settings of Hart Hemmings' novel. While the novel was based on an amalgam of powerful local families, it was still a great honor to meet Princess Abigail, who was born long before Hawaii became the 50th State and who'd lived through its tumultuous history.

How often, after all, does one have the chance to meet true American royalty?

Julia Flynn Siler is the bestselling author of "Lost Kingdom: Hawaii's Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America's First Imperial Adventure," published by the Atlantic Monthly Press. For more information, please visit www.juliaflynnsiler.com

March 9, 2012

Retracing Lili‘u’s Footsteps…

Purely by chance, I found myself in the Washington, D.C. neighborhood where Hawai‘i’s last queen, Lili‘uokalani, had once lived.

I was in Washington, D.C. to deliver a talk to a group of Treasury executives about my new book, Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure. I’d booked a hotel near Dupont Circle.

The evening after the Treasury talk, I was on my way to a dinner party thrown by a group of college friends and stopped at Cairo Wine & Liquor, a small shop a few blocks away from my hotel, to pick up a bottle of wine.

The shop’s name caught my eye and I asked the man behind the counter whether the Cairo apartment building was nearby.

“Sure is,” he answered, motioning across 17th Street, to 1615 Q Street, N.W. “It’s right around the corner.”

“That’s where Hawai‘i’s last queen once lived… “ I said, as I handed him my credit card.

Historic photo of the Cairo Hotel

I’d visited the building four years ago, early on in my effort to retrace Lili‘u’s steps. I hadn’t remembered where it was, but distinctly remembered the gargoyles on the outside and dramatic Romanesque entry arch.

“Before or after she was kicked off the throne?” he asked, shaking his head.

“Afterwards,” I said, a bit surprised that the man at the register, who was perhaps in his late forties, knew the history that had led to the end of the independent Kingdom of Hawaii. I am about his age and this episode of American history was never taught in any of my classes growing up.

I walked out of the shop, having found a connection between a U.S. Marine-backed coup that had taken place 119 years earlier in a remote island kingdom and a Washington, D.C. liquor store.

Lili‘u had arrived in the nation’s capitol in January of 1897, where she moved into what was then a chic luxury hotel. In her suite of rooms, she penned her autobiography, Hawaii’s Story, working closely with the American journalist Julius Palmer in an ultimately unsuccessful effort to regain her throne by swaying public opinion and privately petitioning President Grover Cleveland.

The next morning, I decided to revisit the Cairo – the building, not the liquor store. When it was constructed in 1894, it was the tallest building in Washington, at a soaring 156-feet. Concerns over its safety led the city to pass local height restriction legislation and for many years, it remained the capital’s tallest residential building.

When Lili‘u moved there in 1897, it had 350 rooms, suites on every floor, a dining room, a grand ballroom, a nightclub, a billiard room, a barbershop, a bowling alley, and (best of all) a tropical garden on its rooftop terrace. In her suite of rooms, Lili‘u would work most mornings in front of an open fireplace with a gas log, translating the lyrics of the hundred of so songs she had composed into English, as well as completing her autobiography.

The Cairo went downhill in the decades after Lili‘u lived there. As the neighborhood around it decayed in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, it served as a student hostel, a temporary shelter for the needy, and finally, a flophouse. It closed in 1972, was sold and renovated into larger apartments over three years.

In 1993 – the centennial of the overthrow and the same year that President Clinton issued a formal apology to the people of Hawai‘i – the Washington Post described the Cairo as sitting like “some massive Byzantine dream” in the midst of a bustling urban neighborhood.

My quick trip to Washington was so much richer for having rediscovered the Cairo. A heartfelt thanks (or mahalo in Hawaiian) to my new friend at the other Cairo (where I bought the bottle of Sonoma-Cutrer) for pointing out this wonderful building.

Retracing Lili'u's Footsteps…

Purely by chance, I found myself in the Washington, D.C. neighborhood where Hawai'i's last queen, Lili'uokalani, had once lived.

I was in Washington, D.C. to deliver a talk to a group of Treasury executives about my new book, Lost Kingdom: Hawaii's Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America's First Imperial Adventure. I'd booked a hotel near Dupont Circle.

The evening after the Treasury talk, I was on my way to a dinner party thrown by a group of college friends and stopped at Cairo Wine & Liquor, a small shop a few blocks away from my hotel, to pick up a bottle of wine.

The shop's name caught my eye and I asked the man behind the counter whether the Cairo apartment building was nearby.

"Sure is," he answered, motioning across 17th Street, to 1615 Q Street, N.W. "It's right around the corner."

"That's where Hawai'i's last queen once lived… " I said, as I handed him my credit card.

Historic photo of the Cairo Hotel

I'd visited the building four years ago, early on in my effort to retrace Lili'u's steps. I hadn't remembered where it was, but distinctly remembered the gargoyles on the outside and dramatic Romanesque entry arch.

"Before or after she was kicked off the throne?" he asked, shaking his head.

"Afterwards," I said, a bit surprised that the man at the register, who was perhaps in his late forties, knew the history that had led to the end of the independent Kingdom of Hawaii. I am about his age and this episode of American history was never taught in any of my classes growing up.

I walked out of the shop, having found a connection between a U.S. Marine-backed coup that had taken place 119 years earlier in a remote island kingdom and a Washington, D.C. liquor store.

Lili'u had arrived in the nation's capitol in January of 1897, where she moved into what was then a chic luxury hotel. In her suite of rooms, she penned her autobiography, Hawaii's Story, working closely with the American journalist Julius Palmer in an ultimately unsuccessful effort to regain her throne by swaying public opinion and privately petitioning President Grover Cleveland.

The next morning, I decided to revisit the Cairo – the building, not the liquor store. When it was constructed in 1894, it was the tallest building in Washington, at a soaring 156-feet. Concerns over its safety led the city to pass local height restriction legislation and for many years, it remained the capital's tallest residential building.

When Lili'u moved there in 1897, it had 350 rooms, suites on every floor, a dining room, a grand ballroom, a nightclub, a billiard room, a barbershop, a bowling alley, and (best of all) a tropical garden on its rooftop terrace. In her suite of rooms, Lili'u would work most mornings in front of an open fireplace with a gas log, translating the lyrics of the hundred of so songs she had composed into English, as well as completing her autobiography.

The Cairo went downhill in the decades after Lili'u lived there. As the neighborhood around it decayed in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, it served as a student hostel, a temporary shelter for the needy, and finally, a flophouse. It closed in 1972, was sold and renovated into larger apartments over three years.

In 1993 – the centennial of the overthrow and the same year that President Clinton issued a formal apology to the people of Hawai'i – the Washington Post described the Cairo as sitting like "some massive Byzantine dream" in the midst of a bustling urban neighborhood.

My quick trip to Washington was so much richer for having rediscovered the Cairo. A heartfelt thanks (or mahalo in Hawaiian) to my new friend at the other Cairo (where I bought the bottle of Sonoma-Cutrer) for pointing out this wonderful building.