Julia Flynn Siler's Blog, page 7

June 9, 2014

Devotees of the Bancroft Library: “We’re archive rats!”

This past Saturday, I jumped in my car and headed to Berkeley to attend the annual meeting and luncheon of the Friends of the Bancroft Library. I love this University of California campus, especially U.C. Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, which houses some of the most precious and rare manuscripts of the American West. That day, I met other people — historians, authors, and avid readers – who are also devoted to preserving and supporting the library’s treasures. It was a gathering of fellow “archive rats.”

I worked in the Bancroft while researching both of my books. For The House of Mondavi, I found a wonderful resource in the Bancroft’s Regional Oral History Office, which conducted a series of oral histories with California’s leading winemakers, including Robert and Peter Mondavi, as well as Miljenko (Mike) Grgich, Jack Davies, and Warren Winiarski.

For Lost Kingdom, I found materials related to both Hawaii’s royal family and to San Francisco’s colorful Spreckels family, including an 1890 pamphlet describing a secret society that Hawaii’s King David Kalākaua was involved with, (the Hale Nauā society, also known as the Temple of Science”)

Over the weekend, I was one of nine people elected to join a distinguished group: the Council of the Friends of the Bancroft Library, which helps support this great public institution. The library was founded in 1905 when the University of California acquired historian Hubert Howe Bancroft’s personal collection, which included priceless documents, such as those of General Mariano Guadelupe Vallejo, a Californio military leader.

Over the weekend, I was one of nine people elected to join a distinguished group: the Council of the Friends of the Bancroft Library, which helps support this great public institution. The library was founded in 1905 when the University of California acquired historian Hubert Howe Bancroft’s personal collection, which included priceless documents, such as those of General Mariano Guadelupe Vallejo, a Californio military leader.

Today, it includes the Mark Twain Papers and Project, the Regional Oral History Office, the University of California Archives, the History of Science and Technology Program, the Pictorial Collection, and the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life. It has become one of the largest — and busiest — special collections in the United States. Elaine C. Tennant oversees it all as the library’s director.

The current projects at the Bancroft include everything from a new series of oral histories with pioneering African-American faculty at U.C. Berkeley titled “The Originals,” to a new exhibition, “Saved by the Bay: The Intellectual Migration from Fascist Europe to UC Berkeley” at The Magnes Collection. Just closing is a marvelous exhibit on “Comics, Cartoons, and Funny Papers” – based, in part, on the Rube Goldberg papers housed at the Bancroft.

Robert M. Senkewicz (left) Rose Marie Beebe (center) and Susan Snyder (right) at the presentation of the Hubert Howe Bancroft Award on June 7, 2014

It was a special treat to meet one of the recipients of this year’s Hubert Howe Bancroft award – Rose Marie Beebe, who received it for her work on early California history with her husband and colleague at Santa Clara University, Robert M. Senkewicz. They teach the Spanish language and history and are now involved in a mammoth project to translate Vallejo’s five-volume memoir from Spanish into English.

“Vallejo is finally going to have his voice,” said Beebe, after accepting the award from the Bancroft’s highly respected outgoing head of public service, Susan Snyder. “He’s my man!” Beebe also fulsomely praised Snyder, whom she’s worked with for many years: “I call her the Goddess,” she said.

I identified with how Beebe described herself and her husband, who have spent countless hours with the Bancroft’s collection for their books Lands of Promise and Despair: Chronicles of Early California, 1535-1846, Testimonios: Early California through the Eyes of Women, 1815-1848 and the Guide to Manuscripts Concerning Baja California in the Collections of the Bancroft Library which they edited.

As Beebe said at the ceremony, “We love primary sources,” she said. “We’re archive rats!”

July 15, 2013

Dispatches From Squaw’s Annual High-Altititude Literary Gathering

Almost a decade ago, I joined the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley for an intensive, week-long non-fiction workshop. It was a summer camp-like experience in the high Sierras. Each morning, about a dozen of us in the non-fiction workshop gathered around a table to critique each other’s manuscripts — usually discussing two submissions each morning. In the afternoons, we’d either stay for the craft talks or hike through the mountains. After dinner, we’d stay up late, swapping stories with fiction and non-fiction writers alike.

That week in Squaw in August of 2004 was both scary and inspiring, in part because the caliber of the teachers was so high. Coming back for more, I came back again the following summer. Joining the Community of Writers at Squaw was critical to my taking the leap from being a newspaper reporter to an author. To this day, I remain deeply grateful for the experience and for the many friendships that began in that high-altitude setting.

[image error]

For one, Squaw led me to my literary agent and friend Michael Carlisle, who founded Squaw’s non-fiction program and is a co-founder of the New York-based literary agency Inkwell Management. It also helped me reconnect with someone who I’d first met as a teenager and who, in the subsequent years, built a remarkable career as a journalist, author, and media entrepreneur: Frances Dinkelspiel.

Like me, Frances had graduated from Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism and was a longtime newspaper and magazine reporter. She was also hoping to take her writing to the next level by writing a book. The result was her magnificent biography, Towers of Gold: How One Jewish Immigrant Named Isaias Hellman Created California (St. Martin’s Press, 2008.)

After spending that week together at Squaw’s non-fiction workshop in 2004, Frances invited me to join her long-standing writing group, North 24th Writers (named at a time when all ten of the writers in the group lived north of San Francisco’s 24th Street in the Noe Valley. Now that the Stanford-based historian Leslie Berlin, author of The Man Behind the Microchip: Robert Noyce and the Invention of Silicon Valley (Oxford University Press, 2005), has joined North 24th, our name is not entirely accurate, but we’re still sticking with it even so.

The non-fiction workshop helped me expand an early draft of my first book, The House of Mondavi: The Rise and Fall of an American Wine Dynasty (Gotham Books, 2007) during my second visit to Squaw. After that, I wrote a narrative history, Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure (Grove/Atlantic, 2012). Michael Carlisle beautifully represented both of my books.

Now, eager for fresh ideas as I head into my third book, I headed up to Squaw again this summer, sitting in on one of Michael’s workshops and attending the public literary events in the afternoons and evenings. Joining me was my friend and fellow North 24ther, Allison Hoover Bartlett, who wrote The Man Who Loved Books Too Much: The True Story of a Thief, A Detective, and a World of Literary Obsession (Riverhead, 2010.)

Allison and I could only stay for a few, mid-week days, but we especially enjoyed the book editors’ panel, which was moderated by Michael Carlisle on Thursday, July 11th. Michael teasingly asked Ann Close, who is Alice Munro’s longtime editor, about Knopf publishing E.L. James’s bestseller, 50 Shades of Grey.

Knopf never published the book in hardcover, but instead decided to publish it only in paperback and as an e-book. Typically, if a publisher thinks a book is unlikely to make it into the review pages, it will publish it as a less costly paperback.

“We figured we’d sell 50 Shades without reviews and I had the sneaking suspicion we didn’t want the Knopf name on it…” Ms. Close admitted to the audience of about 150 people. “But we did want the profits!”

It was widely reported that Random House, which owns the Knopf imprint, awarded all of its employees a $5,000 bonus based on the erotic novel’s success (particularly, as an e-book, offering its readers relative anonymity)

Jokingly referred to as 50 Shades of Green, the book topped the New York Times paperback best-seller list for 37 weeks.

Another funny story from the book editors’ panel came from Reagan Arthur, who recently became the publisher of the venerable Little, Brown & Co. and was quoted in the New York Times this past weekend in a story by London-based Sarah Lyall about J.K. Rowling’s pseudonymously published debut detective novel.

Ms. Arthur described working with comedienne Tina Fey on her bestseller, Bossy Pants (the title, according to Ms. Arthur, came from Fey’s husband.) Ms. Arthur admitted to having some doubts about the arresting cover art of Fey with a big, hairy, man’s arms.” So the publisher decided to do market testing on the cover art.

“Everybody loved the arms,” Ms. Arthur recalls, adding that Fey quipped afterwards to her that it “was the only time market testing ever worked in my favor!”

I also learned a bit more about the publishing trade terms that were tossed around during the panel.

From Knopf’s legendary senior editor Ann Close, we heard the term “figures” – which is the publisher and editor’s educated guess on how many copies of a book it might print and ship. Before bidding on a manuscript, the acquiring editor will give the “figures” to Knopf’s accountants and ask for a profit and loss statement. Close says that when she first started in the business in 1970, the practice was “just kind of to make up an estimate of what the book would sell and what kind of advance they could pay the author.”

From Reagan Arthur, Little Brown’s publisher: “track” as in an author’s track record for sales of his or her previous record. “Track does matter,” says Arthur, but then told the story of Maria Semple, the author of the bestselling novel, Where Did You Go, Bernadette? which was published four years after her 2008 sleeper, This One Is Mine. Because her first book didn’t sell many copies, Little, Brown could only offer Semple a modest advance for her second book. But, as Arthur explained, it “went on to be a very happy story!” (This hilarious book became a national bestseller.)

From Carolyn Carlson, the executive editor of Viking Penguin: the code for authors who are gorgeous or charismatic is that they are “marketable.” The code for authors (or potential authors) who have 100,000 twitter followers, or are married to the biggest bookseller in the Northeast, or who work for powerful news outlets, is that “they have a great platform.”

Other bright spots from the public events at Squaw were the published alumni readings by Amy Franklin-Willis, who wrote The Lost Saints of Tennessee (Atlantic-Monthly Press, 2012) and Alison Singh Gee, from her memoir, Where the Peacocks Sing: A Palace, A Prince, and the Search for Home (St. Martin’s, 2013)

Amy, as it turned out, is a good friend of Squaw alum and novelist and Alison is friends with Squaw alum and dear friend Dora Calott Wang, author of the wonderful memoir, The Kitchen Shink: A Psychiatrist’s Reflections on Healing in a Changing World (Riverhead, 2011)

Other highlights were screenwriter Gill Dennis’s craft talk on “Finding the Story.” It was just as inspiring as it was the first time I heard it almost a decade ago. Between panels, I had the chance to sit down with Gill, documentary filmmaker Christopher Beaver, and Martin J. Smith, a longtime editor and journalist in the L.A. area and author most recently of The Wild Duck Chase: Inside the Strange and Wonderful World of the Federal Duck Stamp Contest, was a pleasure: Marty and I many years ago overlapped as reporters at the Orange County Register.

I also met the well-known Hawaiian singer and author Waimea Williams, who gave a craft talk on Saturday titled “How To Be Your Own Editor.” She is the author most recently of Aloha, Mozart (Luminis Books, 2012) and, as it turned out, have friends in common in Hawaii. In western literary circles, the circle of Squaw alums is very large indeed.

January 25, 2013

Book group pick: Lost Kingdom is now out in paperback!

Mahalo nui loa – Hawaiian for thank you very much – to the dozens of book groups I’ve spoken with from around the country that have picked Lost Kingdom as their monthly or quarterly read. I’ve met some of these groups in person and have skyped with some and phoned in to others. It’s been a wonderful experience and now that Lost Kingdom is just out in paperback, I hope to meet with even more groups (including Pamela Feinsilber’s group at Book Passage in Corte Madera this coming Monday, January 28th, as well as a group in Healdsburg soon after that.

I’m truly grateful to all of you – from Liz Epstein’s Literary Masters groups (10 book groups in the San Francisco Bay Area) to the marvelous ladies of the Hawaiian Historical Society, to the book group that met in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights and included descendants of the Dillingham family as well as an astonishing pineapple cake, to Catherine Hartman’s lovely group of Stanford alum and other book-loving friends in Chicago to Jason Poole (The Accidental Hawaiian Crooner) who also organizes a reading group in Pittsburgh. I’m especially grateful to Julie Robinson of Literary Affairs, who organizes book events and moderates book groups in Beverly Hills and the Los Angeles area, for choosing Lost Kingdom as one of her recommended reads.

Here are some questions to discuss on Lost Kingdom that come from Liz Epstein at Literary Masters and adapted by Beth Baily Gates, who’s been running the Fairfax Public Library’s book group for nearly a decade. Hope they’re helpful and if you have other questions, I’d be delighted to skype or phone into your book group for a chat if my schedule permits: here’s the link to request me.

Points to Ponder for Lost Kingdom

Whose story is Lost Kingdom and who should be telling it? Do you think Julia Flynn Siler, a mainland writer, does a good job of showing all sides of this story about nineteenth century Hawaii? Do you think it is an important story?

Is there a hero/heroine or villain/villainess in this story?

How do you feel about Hawai’i’s last ruling queen, Lili’uokalani? Could she have done anything to alter the course of historical events? Should she have? Do you consider her a tragic figure?

How do you feel about King David Kalakaua? How responsible was he for the course of events?

How do you feel about the way the United States handled the annexation of Hawaii? Grover Cleveland claimed “Hawaii is ours…as I contemplate the means used to complete the outrage, I am ashamed of the whole affair.” Do you agree/ disagree with him?

How do you feel about the way the Hawaiians handled the annexation of Hawaii? Did you get a good sense from the book as to how and why they behaved as they did?

What surprised you about Claus Spreckels? What about Dole? Are there other characters in the book that you feel played a pivotal role and you’d like to know more about them?

What were the motives of the original missionaries in coming to Hawaii, and then how do you feel about their descendents? Was everyone generally well-intentioned, or was self-interest paramount?

What is the relevance of this history for us today?

Can you imagine an alternate history? Where would Hawaii be today if the US hadn’t annexed it? Where would the US be today without Hawaii?

This was our non-fiction selection for the season. Do you think this particular history of Hawaii could be better told as ‘historical fiction’?

December 28, 2012

Hau’oli Lānui from San Francisco….

My husband and I went to several holiday parties this year and perhaps the most heartfelt took place in early December, at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center in San Francisco.

We were invited to the J-Town hui’s annual holiday show and potluck. The hui (Hawaiian for a club or association) was made up of students in the music and vocal classes led by a beloved and longtime Hawaiian music teacher in the city named Carlton Ka’ala Carmack. There were ukeleles, hula performances, and mountains of delicious food. As the island saying goes, it was real ono!

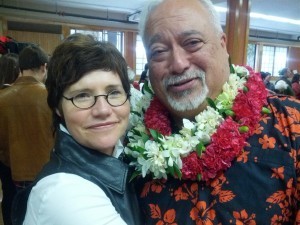

Julia Flynn Siler, author of “Lost Kingdom” (left) and Carlton Ka’ala Carmack, Hawaiian music teacher (right) in Dec. 2012

Ka’ala grew up on Oahu and performed in a play written by John Dominis Holt, whose 1964 essay “On Being Hawaiian” helped spark the Hawaiian Renaissance movement. Also known as Dee, Ka’ala moved to San Francisco in 1978 and played a key role in educating a new generation of students in the Bay Area on the subtleties of Hawaiian music.

An ethno-musicologist who speaks six languages and a gifted singer and musician, Ka’ala’s done everything from serving as an artist-in-residence for the Institute for Diversity in the Arts at Stanford University to teaching a pilot course in Pacific Islander Studies at San Francisco State University.

For more than a decade, Ka’ala directed the J-Town Hui, a well-loved ukulele and vocal ensemble based out of the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California (JNCCNC) where he teaches ukulele classes and a course called “Hawaiian Expressive Singing.”

Members of the J-Town Hui performed at Roy and Kathy Sakuma’s 41st Ukelele Festival in Honolulu in July of 2011 and at the Maui Ukelele Festival in Kahului, Hawai’i last fall.

I got to know Ka’ala when he very kindly agreed to play some of Queen Lili’uokalani’s songs at a gathering for the launch of my book, Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure, earlier this year.

After that, we did a number of events together – including appearing on KQED’s Forum show with Michael Krasny, the Foothill College Authors Series in Silicon Valley for Pacific Islander month, and as keynoters at this year’s Hawaii Book and Music Festival in May.

If you’d like to hear Ka’ala, he composed and performed the music for the recently released documentary, “Towards Living Pono,” produced by the award-winning filmmaker, Rick Bacigalupi. (Pono is a Hawaiian word with many meanings, including goodness, uprightness, morality.) You can also watch him perform Queen Lili’uokalani’s Aloha Oe here.

Patrick Makuakane, the hulu kumu of San Francisco’s well known Na Lei Hulu troupe was also at the party to pay his respects to Ka’ala. He was one of a large number of people who waited in line to greet and thank him.

The afternoon of ukulele playing, hula dancing, singing, and a lot of hugging was made even more poignant because it was also a goodbye party for Ka’ala, who is taking a job teaching chorus, voice, and an introduction to Hawaiian music at the Windward Community College on Oahu starting this spring.

Hau’oli Lānui (happy holidays in Hawaiian) and aloha, Ka’ala. See you soon in the islands!

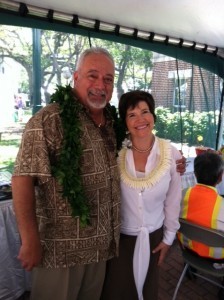

Carlton Ka’ala Cormack (left) and Julia Flynn Siler (right) at the Hawaii Book and Music Festival in May, 2012

November 26, 2012

Creating: Tips From a Wine Therapist

![[image]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380928428i/3329995._SX540_.jpg)

Annie Tritt for The Wall Street JournalLarry Stone at Quintessa Vineyard in Rutherford, Calif.

Master sommelier Larry Stone scans the wine list of a restaurant in Yountville, Calif., and lifts his eyebrows in surprise.

As someone who estimates that he’s tasted nearly a million wines over three decades, he spots one that he doesn’t like on the list. He frowns and instead orders his companion a glass of a 2009 French white wine from the Macon region to accompany a filet of sole. He explains that in wines such as these from the southern end of Burgundy, a combination of rose quartz and pink limestone in the soil imparts a complex mineral taste.

Mr. Stone, 61, is a wine teacher and the estates director for Huneeus Vintners. The heart of what he has done over his long career as one of the country’s best-known wine stewards—he formerly worked for Chicago’s Charlie Trotter and as a partner in San Francisco’s Rubicon restaurant—is to use his encyclopedic wine knowledge to determine what diners might like to drink to accompany their food. His goal: to delight and sometimes surprise them.

“You’re there to listen,” he says. “You have to listen well, otherwise you may totally misunderstand what they need and want.”

From an early age, Mr. Stone, who grew up in Seattle, was an avid reader with a prodigious memory. At age 16, he enrolled in a university program, studying chemistry. On the side he made bootleg whiskey by distilling alcohol, marinating oak chips and adding caramel coloring. Within a few years, he had mastered Alexis Lichine’s 713-page “Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits.”

In 1981, after more than a decade working slowly toward a Ph.D. in comparative literature, he interviewed for a job as an assistant sommelier at a Seattle restaurant. The owner tested him with some questions taken from Mr. Lichine’s book, such as what is the variety of grapes used in the Hungarian red wine Egri Bikaver and what is Gumpoldskirchen (a small village in Austria that produces white wines). Mr. Stone knew the answers and got the job—despite having no experience as a wine steward.

Although he never did get his Ph.D., in 1988 he passed the famously difficult Master Sommelier exam after only a few months of study. (It often takes candidates four to six years of repeated attempts to pass the rigorous testing.) That same year, he won a contest as the world’s Best Sommelier in French Wines, held in Paris.

“He’s a brilliant sommelier. One of the finest I’ve ever examined,” says Fred Dame, who founded the Court of Master Sommeliers’ U.S. branch. Passing the test takes not only an ability to identify the vintages, vineyards and vintners of wines during blind tastings, but also broader skills in educating clients about wine and acquiring and managing large wine collections.

The following year, he was recruited to join the Four Seasons, then moved to Charlie Trotter’s in Chicago, and finally joined Francis Ford Coppola, Robert De Niro, Robin Williams and restaurateur Drew Nieporent as a partner in the restaurant Rubicon in San Francisco. (He left Rubicon in 2008 to manage Mr. Coppola’s wine estate until 2010, and Charlie Trotter’s closed in August.)

A Matter of Taste

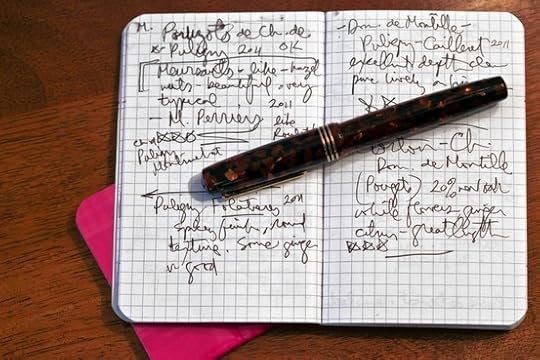

![[image]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380928428i/3329996.jpg)

Annie Tritt for The Wall Street Journal

Larry Stone samples Cabernet, still warm from fermentation, at the Quintessa winery, left. He prefers to do important tastings early in the day, before breakfast, and avoids eating peppery foods or drinking coffee beforehand.

He takes detailed tasting notes by hand, such as these from a recent trip to Burgundy, assigning two and three stars to wines he might eventually want to buy. For rare-wine tastings, he transfers his notes onto his computer.

In the book “Secrets of the Sommeliers,” co-author Rajat Parr recalls the Saturday afternoon tasting tutorials that Mr. Stone long hosted for his staff at Rubicon. Each attendee was required to bring a bottle of wine wrapped in a paper bag to share with the group. Mr. Stone believes that blind tastings are one of the best ways to learn about wine.

Being a sommelier has some similarities to being a therapist: Good listening skills are a must. Early in his career, a guest complained that the bottle of white wine he’d ordered tasted salty. The waiter was stumped and skeptical. Mr. Stone brought the customer another bottle, and then a third—until finally, he found one to the guest’s liking (a Heitz Cellar Chardonnay). Mr. Stone recalls the guest, who soon became a regular at the restaurant, told him, “No one’s ever listened to me before. People dismissed me as a crackpot.”

Over the years, he helped to persuade some die-hard Bordeaux fans to branch out and drink wines from the Rhône, particularly Viognier, a white wine varietal grown in the Condrieu region. He was likewise an advocate for the Austrian white known as Grüner Veltliner, which Charlie Trotter and other chefs found paired well with food.

The job requires stamina. Mr. Stone estimates that between the early 1980s and 2008, he tasted up to 100 bottles of wine a day, five days a week, and typically worked more than 300 days (and, often, nights) a year.

Because that work was so physically demanding, he’s now focused on bringing up the next generation of sommeliers. He was recently named a dean of wine studies at the International Culinary Center in Campbell, Calif., and just became estates manager for Agustin Huneeus’s wine properties, which include Napa’s Quintessa, Sonoma’s Flowers and Chile’s Neyen wineries—helping to develop the style of the wines, among other duties.

Still, he says, some of his favorite moments have been finding the perfect wine for someone, even when the guest has trouble finding the right words. “I enjoy improvising,” he says.

Write to Julia Flynn Siler at julia.flynn@wsj.com

October 31, 2012

So you want to start a writing group…

A hand popped up in the back of the room. “So where did you get your name?” asked a man last Sunday afternoon. Seated before him were four members of North 24th Writers, who’d gathered at Book Passage for a panel discussion on writing groups.

The occasion was the monthly meeting of the Marin branch of the California Writers Club, a group incorporated in 1913 that had Jack London as one of its first members. About forty people had decided to spend a few hours during a beautiful fall afternoon inside (shortly before the Giants won the World Series) to hear a discussion about writing groups, including how to form them, and the challenges and surprising side-benefits of creating your own work group.

Allison Hoover Bartlett, author of “The Man Who Loved Books Too Much” speaking at the California Writers Club’s October meeting

But the name of the critique group was puzzling to some. So here’s our story.

North 24th Writers is a long-established writing group made up of ten Bay Area women who’ve collectively published ten nonfiction books as well as hundreds of articles and essays in magazines, journals, and online publications. It is one of the Bay Area’s best-known writing groups.

Allison Hoover Bartlett, the author of The Man Who Loved Books Too Much and one of the founding members of North 24th Writers, explained the group’s name, which came from where its members live: all of us live north of San Francisco’s 24th Street.

Most of the group’s ten writers are based in San Francisco, including Bartlett and Susan Freinkel, author of Plastics: A Toxic Love Story and American Chestnut. But Frances Dinkelspiel, author of Towers of Gold, lives in Berkeley, and both Katherine Ellison, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of five books, including Buzz and The Mommy Brain, and Julia Flynn Siler, author of Lost Kingdom and The House of Mondavi, live in Marin.

Bartlett was one of the writers who spun North 24th Writers out of Jane Anne Staw’s creative nonfiction work in the late 1990s. A few people came and went over the years, but since 2006, it’s been the same group of writers—all of whom began writing non-fiction, though now two have branched out into fiction. Over the years, we’ve learned a few lessons:

-Define your purpose early on. For North 24th Writers, our primary focus is on the craft of writing. We spend most of our time critiquing each other’s work, but allot some time to discuss the business of publishing, marketing, etc..

-Establish rules that everyone agrees. North 24th meets twice a month for two and a half hours each time. We sign up in advance to submit writing that the group will critique, submitting pieces no later than five days before the workshop.

-Choose the right partners. You might start by joining a critique class and then finding fellow students who you might want to continue working with. Don’t be discouraged if no one in your first class seems like a good fit—keep taking classes.

Susan Freinkel (front) author of Plastics: A Toxic Love Story, and Kathy Ellison, author of Buzz at the CWC’s October meeting at Book Passage

As Bartlett joked, taking a class to find compatible writing partners is “like going on a real date rather than browsing Match.com.”

-Read out loud. One of the best ways to find out how a piece of writing is working is to begin by reading it out loud to your group. You’ll immediately sense which rhythms and word choices are working—and those that aren’t.

-Sandwich your criticism. Start with the positive then move onto specific comments about what parts of the writing did and did not work, including specific suggestions on how to address those issues. Finish up with something positive.

-Friendships in a group can become a handicap. Over the years, the members of North 24th have become good friends. But the risk is that the group can become too safe and lose track of its original purpose. Be aware of this and don’t pull your punches (just sandwich them!) As Gil Mansergh, who attended the panel and has his own longstanding writing group observed, “even though you’re dealing with somebody’s babies, don’t be too nice!”

-Staying committed. Everyone is busy, but if the group becomes lackadaisical about scheduling meeting times, it can easily fall away. Block out your monthly workshop time together and keep those times sacrosanct.

Towards the end of the discussion, the James Beard award-winning cookbook writer Lorna Sass, thanked the panel for sharing its experiences with the group.

“The beauty of what your doing is that it dispels the myth that we should be doing this alone,” she observed. We agree. By creating our own community, we’ve helped each other become better writers.

Bartlett and Freinkel having fun on a panel on writing groups at Book Passage

October 25, 2012

Call Me Ishmael: Herman Melville and the San Francisco Opera

It is one of the most memorable first sentences of a novel ever written. With three simple words, it draws us into the story, lets us know who the narrator is, and hints at dramatic transformations to come.

This opening line – Call me Ishmael – was written by Herman Melville in his epic about Captain Ahab’s quest to kill the white whale Moby Dick. One of the surprises of the San Francisco Opera’s current production of Moby Dick is that this line is used in a different way in the story – to very good effect. I won’t spoil the pleasure in telling you how, but would urge you to see this opera yourself.

The cast of San Francisco Opera’s performance of Moby Dick Photo by Corey Weaver.

Born in New York City in 1819, Melville spent four years during his twenties (1841-1845) working on whaling ships. He began as a cabin boy on a whaler heading from Massachusetts, around Cape Horn, to the Pacific. He lived amongst the Typee, took part in a mutiny, and worked for a time as a pin setter in a bowling alley in Honolulu.

Melville was one of the more interesting characters to land in Hawaii during the first half of the nineteenth century, when the whaling industry was at its height. His impressions from that time are notable for their bite: he was no fan of the Christians who came from Massachusetts and other eastern states to spread the word of God to the native Hawaiians.

Unimpressed with the quality of the Westerners who became courtiers to King Kamehameha III, he described them in a footnote to his first novel, Typee, as “a junta of ignorant and designing Methodist elders in the council of a half civilized king ruling with absolute sway over a nation just poised between barbarism and civilization.”

Aside from getting their religion wrong – the missionaries who came to Hawaii were mostly Congregationalists, not Methodists – and insulting Hawaii’s king, Melville did capture the sense of change sweeping over the kingdom. Since the Missionaries first arrived in Hawaii in 1820, they’d given the Hawaiians, whose culture up until then had been oral, an alphabet and printing presses. By the 1840s, a flowering of literacy was taking place in Hawaii.

Jonathan Lemalu (Queequeg) and Stephen Costello (Greenhorn) in SF Opera’s Moby Dick. Photo by Cory Weaver.

Watching the opera of Moby Dick last week, I couldn’t help but think about Melville, who makes a cameo appearance in my history of Hawaii, Lost Kingdom. As someone who loves language, I was awed by the work of Gene Scheer in turning his sprawling, 800 or so page opus, into the 60-page libretto for the opera Moby Dick.

In the novel, Ishmael narrates the story – looking back in time. Instead, Scheer set all the action on the whaling ship. The narrator who begins with the famous line Call Me Ishmael is gone – at least in the role as the person telling the story.

Jane Ganahl, Litquake’s co-founder, profiled Scheer in the opera’s program notes. She also helped organize a Litquake event with the librettist on October 8th that I truly wish I could have attended. He told her that one of the key challenges in adapting a book into another medium is that “people don’t want to see people on stage telling the story, they want to be shown the story. I struggled with how to get at the truth of the story, until I had a breakthrough, and realized I should have the story unfold through the eyes of Greenhorn, the only person who had never been on a whaling ship. His is a transformative journey.” (Greenhorn is the character in the photo smoking a pipe — and baritone Jonathan Lemalu was wonderful as Queequeg.)

Perhaps the most powerful magic for me in the opera was Scheer’s use of Melville’s language. Scheer estimated that at least half the libretto was taken directly from the book. Set to music and sung, the words were more like poetry than prose. Melville’s words set to Jake Heggie’s music was powerful and profoundly moving.

Jay Hunter Morris (Captain Ahab). Photo by Cory Weaver.

October 5, 2012

Spoiled for choice…

There always seems to be one weekend in the fall when there’s just too much going on. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, this weekend boasts not only Hardly Strictly Bluegrass, the free music festival in Golden Gate Park founded by the late philanthropist and financier Warren Hellman, but also Fleet Week. And it’s the first weekend of Litquake, the city’s rocking literary festival. Not to mention this Saturday night is the annual party for Adopt-a-Family of Marin, a wonderful non-profit organization that supports local families in need. As an Irish friend once said to my husband Charlie and I when we lived in London, “You’re just spoiled for choice!”

The late Warren Hellman playing his banjo at the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival

I’ll be celebrating Litquake on Saturday from 2-3 p.m. by taking part in the opening “Off the Richter Scale” series. The panel I’m on is called “Around the World, On the Page,” and I’m looking forward to catching up with fellow authors Tamim Ansary, Carolina De Robertis, Zoe Ferraris, and Aimee Phan. But I’m also a bit disappointed because Scott James (whose pen name is Kemble Scott) will be emceeing the “Litquake in the Castro” event – a series of provocative outdoor readings held at Jane Warner Plaza, at the corner of Castro and Market Street, starting at 1:00 p.m. that day. There’s no way for me to make it from the Castro readings to the Variety Preview Room, which is in the financial district, in time to attend both fun events.

After work tonight, I’m headed after work today to exhibit of the BayWood Artists at the Bay Model in Sausalito. The opening reception is this Friday, October 5th, from 5-8 p.m. and the show runs from October 5th through the 26th. One of the Baywood Artists is our dear family friend Zenaida “Zee Zee” Mott. It is truly a reflection of the generous character for Zee Zee and her fellow plein air painters to arrange to donate fifty percent of the sales from this show to support our open space district and the Point Reyes National Seashore. I’ll be there to support her and to also support one of our fabulous nearby park. Join us in Sausalito on Friday night for what will surely be a great evening! (And in another example of the “spoiled for choice” phenomenon, Zee Zee’s grandson Ian Mott will be one of the teens playing in a band at nearby Proof Lab surf shop in Mill Valley tonight. It’s a benefit to raise financial aid funds for less advantage kids to attend the Branson School. I’m hoping to stop in for that, as well!) Sunday, it’s Hardly Strictly and an open house for the Squaw Valley Community of Writers. It’ll take all week to recover…

September 19, 2012

Meeting Hawaii’s Next Generation Authors? (…and How I Handle Criticism)

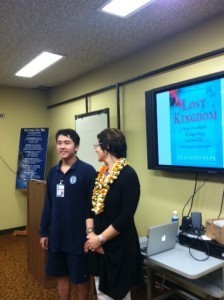

A young man sitting in the back row tentatively raised his hand. I was talking to a group of history students and their teachers at Kamehameha School last week about my book, Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure, published by Atlantic Monthly Press earlier this year. “How do you deal with criticism as an author?” he asked.

Meeting with Hawaiian language immersion students at Ke Kula Kaiapuni o Anuenue

That was a very good question. Lost Kingdom has gotten good reviews in the New York Times Sunday Book Review, the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and elsewhere. There are 57 reader reviews on Amazon and the vast majority of the reviewers gave it four or five stars.

But one reviewer – the author of a book on hula who is herself from the mainland – criticized it in her Amazon reader review on many levels, suggesting that an outsider couldn’t possibly write a sensitive or intelligent book about the islands. Other Hawaiian scholars have criticized me for not having used more Hawaiian-language source materials. Their basic argument is that someone who can’t read the Hawaiian language newspapers of the 19th century can’t write a thorough history of the kingdom.

So how do I handle criticism? In answering the student that day, I started off by joking that after nearly three decades as a reporter, writing for the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and BusinessWeek magazine, my skin had grown pretty thick and that helped me separate professional criticism from my personal feelings. I also told him that I care very deeply about getting things right. That’s one of the reasons why I’ve enlisted the help of scholars and friends to help me make corrections for the paperback version of Lost Kingdom, which will be out at the end of the year.

That was one of the first lessons I learned as a new fact-checker at the American Lawyer magazine, straight out of college. If there’s a mistake, own up to it and make sure it gets fixed. The story and both your and the publication’s reputation are more important than a dented ego. In terms of Hawaiian cultural values, the goal is to be pono – which, roughly translated, means do the right thing. That’s why I’m taking so much care in correcting and updating the new edition of the book. Most of the changes are very small, but it’s important to make them.

Later that same da y, I got an earful from a University of Hawai’i scholar at an event at the Bishop Museum. She pointed out things she didn’t like about it – ranging from my description of a Hawaiian laborer in a sugar mill (she thought I had sexualized him) to her contention that human sacrifices were never made to the goddess Pele. I’m checking out what she said and will fix what’s wrong. But I think she didn’t understand that my goal was never to write an academic history: my goal was to write a book for people who knew little to nothing about the history of the Hawaiian islands. And the reason I included more than 800 endnotes, documenting my source materials, was that so that others could come along and build on my work – telling the story from their own perspectives.

y, I got an earful from a University of Hawai’i scholar at an event at the Bishop Museum. She pointed out things she didn’t like about it – ranging from my description of a Hawaiian laborer in a sugar mill (she thought I had sexualized him) to her contention that human sacrifices were never made to the goddess Pele. I’m checking out what she said and will fix what’s wrong. But I think she didn’t understand that my goal was never to write an academic history: my goal was to write a book for people who knew little to nothing about the history of the Hawaiian islands. And the reason I included more than 800 endnotes, documenting my source materials, was that so that others could come along and build on my work – telling the story from their own perspectives.

Maybe some of the students I spoke to last week might some day write their own histories of Hawaii. And because of efforts such as Awaiaulu Project, led by University of Hawaii Professor Puakea Nogelmeier, they’ll have more source materials to work with through the Hawaiian language newspapers now being translated.

I felt lucky to be able to have so many interesting conversations last week. I was visiting Kamehameha Schools as part of a community dialogue set up by Jamie Conway, founder of the Distinctive Women inHawaiian History program, a wonderful event which took place on Saturday, September 15th, at Mission Memorial Auditorium in downtown Honolulu. I am very grateful to Jamie for arranging what turned out to be a truly unforgettable series of events, taking me places that I’d otherwise probably never have gone on my own.

Nalei Akina of the Lunalilo Home, author Julia Flynn Siler, and Jamie Conway of Distinctive Women in Hawaiian History

I went to the Lunalilo Home, the Bishop Museum (in conversation with “Uncle Ish” Ishmael Stanger, who has a new book out about Hula Kumu (hula teachers,) Kapi’olani Community College, and, most memorably, 150 students and teachers from the Kula Kaiapuni ‘o Ānuenue, a Hawaiian Language Immersion School in Honolulu’s Palolo Valley. These were all volunteer efforts on my part—my small attempt to give back to the community.

Have I planted any seeds? Might any of those kids think more seriously about becoming a writer or a historian, so they can tell stories from their own perspectives, using the newspapers that only now are being translated into English? I do hope so. As I learned from the kids at the immersion school, a key value in Hawaiian culture is Ke Kuleana (to take responsibility.) That’s what I’m doing by making corrections to the new version of my book. Mahalo to all the teachers who are helping me with this task – and also to the teachers such as Thelma Kan, who invited me to join her at dawn for a Hiuwai Ceremony on Sunday morning.

Here’s the chant that Thelma led us in, by Edith Kanakaole

E Ho Mai

E ho mai ka ike mai luna mai e

O na mea huna no’eau o na mele e

E ho mai, e ho mai, e ho mai e

Give forth knowledge from above

Every little bit of wisdom contained in song

Give forth, give forth, do give forth

September 15, 2012

Mark Ho’omalu and a “Kingdom Denied”

“Get your papers!” cried the delivery boys and girls, carrying rolled up copies of a Hawaiian newspaper printed especially for that evening’s show. Wearing natty caps and suspenders, they ran through the aisles clutching copies of the “Star of the Pacific,” yelling, “Get your papers!”

Thus began an extraordinary one-night performance of the musical “Kingdom Denied,” which was written by kumu hula Mark Keali’i Ho’omalu, founder of the Academy of Hawaiian Arts in Oakland, Ca. I’d interviewed Mark for a page one story in the Wall Street Journal last year about mainland hula troupes headlined “Aloha, Lady Gaga.” (You can watch the video that accompanied the story here.)

Having seen him and members of his halau (hula school) perform their high-energy hula in the course of reporting that story last fall, I was happy to attend “Kingdom Denied: Between the Lines” at Chabot College in Hayward last weekend. This ambitious and, at times, very moving rendition of the rise and fall of Hawaii’s last king and queen was well worth the trip.

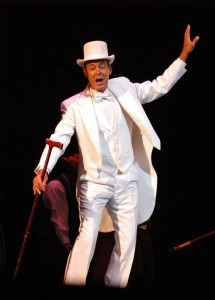

Mark Keali’i Ho’omalu as Ioane “Daddy” Ukeke in “Kingdom Denied”

The evening began with kumu Mark, wearing mirrored sunglasses and a sleeveless white t-shirt, strolled out onto the stage before the show began. Calling for his youngest child, Charles, he held the toddler in his arms as he paid tribute to his fellow kumu hula (hula teacher) Charles Ka’upu, who had recently died. It was a poignant and very sweet way to open the show.

I also enjoyed Mark’s good-natured ribbing of his fellow kumu hula Patrick Makuakane, who was seated in the front row of the packed theater. Patrick’s halau will be staging its well-loved annual extravaganza, “The Hula Show” in San Francisco next month, which I’m looking forward to seeing.

Mark is a powerfully charismatic performer, with a deep, memorable voice. His idea was to tell the story of the final years of the Hawaiian Kingdom through the coverage in the Hawaiian language papers of the time, as well as through Hawaiian songs, hula, and chants. The program notes thank University of Hawaii Professor Puakea Nogelmeier, who is heading up the Awaiaulu Project to translate and preserve a vast store of these historic newspapers.

The number that I found most memorable was the hula ma’i performed in honor of King David Kalakaua. I’d read about this type of hula, which celebrates the genitals and procreative vigor, often explicitly, with lusty movements, but I’d never seen it performed. This one, written for King Kalakaua, was titled “Ko Ma’i Keia” repeated the teasing phrase, “bring it here!”

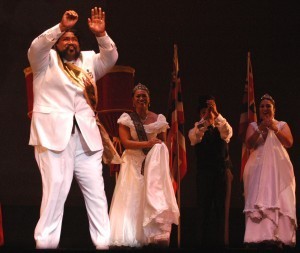

I also loved the casting of historical figures who’d I’ve lived closely with over the past four years, trying to bring them back to life through the papers and photographs they left behind in the archives. Mr. Ray Bambao, the actor playing the King, in all his bewhiskered magnificence, was superbly cast, as were the bountiful Queen Emma (Ms. K. Soukhamthath) and dignified Queen Lili’uokalani (Mrs. C. Fua.)

King David Kalakaua, played by R. Bamboa, and Princess Liliuokalani, played by C. Fua in the American premiere of “Kingdom Denied”

One colorful character I’d never come across before was Ioane “Daddy” Ukeke, a character played by Mark in an all-white three piece suit and top hat. Iolane apparently got his name because of his skill in playing the native Hawaiian stringed instrument, the ukeke. He was also the leader of a hula troupe that often played for King Kalakaua, according to the program notes. But Ioane’s fortunes mirrored those of the Hawaiian monarchy: he went blind and ended up playing his ukeke in the streets of Honolulu in hope that a passerby might drop him a coin or two.

There were a few hiccups with the chronology of “Kingdom Denied” – something that I noticed, as did the friend who joined me that evening, Carlton Ka’ala Cormack, who came with his wife Rosalie. And if Mark and his halau were to perform it again, I hope they might consider devoting more time to the overthrow, and a bit less to the riot that followed the election of King Kalakaua, after defeating Queen Emma.

While I liked the decision to use contemporary news footage for riots all around the world as a way of putting this one in context, the result was that the latter – and arguably more dramatic events of the overthrow, the failed counter-coup, and Queen Lili’uokalani’s imprisonment were a bit rushed.

I hope that “Kingdom Denied” is performed again soon. The idea of a Hawaiian musical is a compelling one; since music and dance has long been the way that history was passed down in Hawaii’s traditionally oral culture. The crowd loved it – leaping to their feet as the curtain went down. The San Francisco Chronicle’s SFgate team of Jeanne Cooper and Emily Tuupo, who produce the paper’s Hawaii blog and Aloha Friday column, seemed to enjoy it as much as I did. Mahalo to Mark, Pat Ravarra, and other members of the halau for inviting me to join them for this memorable evening.

Ray Bamboa as King David Kalakaua