Julia Flynn Siler's Blog, page 3

March 11, 2021

United Nations and Human Trafficking

March is Women’s History Month and I’m thrilled to take part on Friday, March 19th in a virtual panel at this year’s United Nations Commission on the Status of Women NGO Forum.

The event is being organized by the San Francisco Collaborative Against Human Trafficking, a public-private partnership established more than a decade ago by the National Council of Jewish Women and the Jewish Coalition to End Human Trafficking in collaboration with the San Francisco Department on the Status of Women, the San Francisco Human Rights Commission, and the San Francisco Mayor’s Office.

The event is being organized by the San Francisco Collaborative Against Human Trafficking, a public-private partnership established more than a decade ago by the National Council of Jewish Women and the Jewish Coalition to End Human Trafficking in collaboration with the San Francisco Department on the Status of Women, the San Francisco Human Rights Commission, and the San Francisco Mayor’s Office.

I’ll be joining the SFCAHT’s executive director, Antonia Lavine, and its co-founder, Nancy Goldberg, as well as California Superior Court Judge Susan Breall, Emily Murase, the former director of the San Francisco Department on the Status of Women, and Cheryl Hayles, the President of the International Alliance of Women.

I’ll be discussing the late 19th and early 20th century efforts to combat human trafficking detailed in my book, The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Against Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Specifically, I’ll be exploring how anti-trafficking pioneers collaborated with others to achieve their goals.

The event, which will take place on Friday, March 19th, from 12:30-2 p.m., is titled “ABC’s of Global Collaboration To Fight Human Trafficking” and it is part of the San Francisco delegation’s series of events. To participate, you must first register (free!) as an advocate here. (Update: this event is now sold out and registration is no longer possible.)

The post United Nations and Human Trafficking appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

United Nations Commission on the Status of Women Panel: ABC’s of Human Trafficking

March is Women’s History Month and I’m thrilled to take part on Friday, March 19th in a virtual panel at this year’s United Nations Commission on the Status of Women NGO Forum.

The event is being organized by the San Francisco Collaborative Against Human Trafficking, a public-private partnership established more than a decade ago by the National Council of Jewish Women and the Jewish Coalition to End Human Trafficking in collaboration with the San Francisco Department on the Status of Women, the San Francisco Human Rights Commission, and the San Francisco Mayor’s Office.

The event is being organized by the San Francisco Collaborative Against Human Trafficking, a public-private partnership established more than a decade ago by the National Council of Jewish Women and the Jewish Coalition to End Human Trafficking in collaboration with the San Francisco Department on the Status of Women, the San Francisco Human Rights Commission, and the San Francisco Mayor’s Office.

I’ll be joining the SFCAHT’s executive director, Antonia Lavine, and its co-founder, Nancy Goldberg, as well as California Superior Court Judge Susan Breall, Emily Murase, the former director of the San Francisco Department on the Status of Women, and Cheryl Hayles, the President of the International Alliance of Women.

I’ll be discussing the late 19th and early 20th century efforts to combat human trafficking detailed in my book, The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Against Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Specifically, I’ll be exploring how anti-trafficking pioneers collaborated with others to achieve their goals.

The event, which will take place on Friday, March 19th, from 12:30-2 p.m., is titled “ABC’s of Global Collaboration To Fight Human Trafficking” and it is part of the San Francisco delegation’s series of events. To participate, you must first register (free!) as an advocate here.

The post United Nations Commission on the Status of Women Panel: ABC’s of Human Trafficking appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

January 5, 2021

The Safe Place That Became Unsafe

Early on in the research for The White Devil’s Daughters, I learned about a horrific aftermath to the story I was writing. My focus was on a group of women residents and staffers of a historic safe house who fought sex slavery at the turn of the 20th century. One day, while sifting through case files with the home’s retired executive director, she suddenly turned to me and asked, do you know about Dick Wichman?

I didn’t. So, in a somber tone, she told me the chilling story of a sexual predator who, for decades later in the 20th century, abused boys in the very same place where my story was set –the safe house in San Francisco’s Chinatown that my characters had established in the 1870s to protect girls and women.

I felt shock – and soon realized I was facing a challenge. How should I handle the monster in the basement – which was, literally, where the abuse took place? To include him in a book about heroic women could overshadow their story.

The home’s retired director, a woman named Doreen Der-McLeod, gave me fair warning. Before I ventured too far down the path of telling the stories of the brave women who’d fought human trafficking and slavery at the turn of the 20th century, she wanted to make sure that I understood the full horror of what occurred decades after the women had left the home.

I’d planned to begin my book in 1874, when a group of churchwomen founded a safe house for vulnerable women. Thousands of mostly Chinese girls and women took shelter there over seven decades, including several who went on to live remarkable lives. The home’s long-serving director was Donaldina Cameron, and the home was eventually renamed Cameron House in her honor. The book would end with her retirement in the late 1930s.

The person recruited to Cameron House after the women’s’ project had ended was the Rev. F.S. “Dick” Wichman. He became the institution’s first male director, and he created a thriving program for Chinatown’s youth. But he also turned what had been a sanctuary for girls and women into a profoundly unsafe place for boys and young men. As the home’s director from 1947-1977, Wichman was a pedophile who preyed on vulnerable boys. (Both Cameron House and the Presbyterian Church have publicly acknowledged and apologized for his abuse.)

F.S. Wichman (left) and Donaldina Cameron (right), photo courtesy of Cameron House

By one count, there are 40 known victims of Wichman – all of whom he raped or molested when they were boys, and all Chinese. Some estimate the actual number may be in the hundreds. His predations defiled the dreams of Cameron and many others who devoted their lives to fighting sexual exploitation.

In researching and writing The White Devil’s Daughters, I decided to end my story before the period of Wichman’s abuse – ignoring what would happen in the future. I dealt with Wichman in a single paragraph in the acknowledgments. I didn’t want his story to undermine the accomplishments of the women I was writing about.

But it became impossible for me to continue to ignore Wichman’s decades of abuse after The White Devil’s Daughters was published. His story continued to hang over Cameron House like a dark cloud. As the Rev. Gregory L. Chan later described Cameron House, where he’d served as the board chairman and interim executive director, “the place felt like the Bates Motel in Psycho. We had not cleaned up the shrouded energy…”

In the summer of 2019, Cameron House, along with the Chinese Historical Society of America, hosted a large event to discuss The White Devil’s Daughters. Hundreds of people attended, many of whom had long ties to Cameron House and to Wichman.

During this event, and in private conversations afterwards, Wichman’s name arose – again and again. It became clear to me that there remained a crucial, second story to be told about his era at Cameron House. Yet I was reluctant to tackle it. I knew the reporting would force me to dive into the dynamics of clergy sexual abuse – an area that frightened and disturbed me.

It was a Facebook post about a film in the summer of 2020 that finally tipped the scale. A short documentary had been released about Cameron House’s long effort to acknowledge Wichman’s abuse and embark on a long journey of healing. More than a hundred people commented on it in a heartfelt outpouring of solidarity. Elaine Chan-Scherer, a former Cameron House staffer, who played a crucial role in bringing the abuse to light as a whistleblower, tagged me in her post. Because of the release of the film, I realized this was the moment to write about Wichman, who died in 2007. This was the right moment because the community’s healing process was nearly complete.

Wichman’s three decades at Cameron House were antithetical to the spirit that had guided the project of providing a safe place for vulnerable girls and women. It felt right to follow up my book with a detailed investigation of his time at Cameron House.

As a result, my expose, titled “The Safe Place That Became Unsafe,” about Wichman’s era of abuse and the community’s efforts to heal from it, was published in the Winter, 2021 issue of The Journal of Alta California. That gave me the chance to tell the story of the monster in the basement. While there are probably even more stories to be told about the home, they don’t all need to be told in one telling.

***

This essay was adapted for one first published in The Biographer’s Craft, with thanks to its editor Michael Burgan.

The post The Safe Place That Became Unsafe appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

December 30, 2020

Remembering Judy Yung

Judy Yung’s death this month marks the passing of a gifted and generous scholar. Her groundbreaking work in the history of Asian American women paved the way for a new generation of thinkers and writers.

Historian Judy Yung, photo by Laura Morton, courtesy of San Francisco Chronicle

Along with fellow San Franciscans Him Mark Lai and the Philip P. Choy, Judy Yung made an enormous contribution to our understanding of the Asian American experience. Her focus was on women, a group that had been largely been overlooked by scholars. Judy died on December 14 at her home after a fall, at the age of 74.

Born in 1946 and raised in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Yung worked as a librarian in the public library’s Chinatown branch before getting her PhD. in Ethnic Studies at U.C. Berkeley. She went on to become a beloved professor at U.C. Santa. The San Francisco Chronicle’s Sam Whiting wrote a touching tribute to her life.

Yung’s Unbound Voices: A Documentary History of Chinese Women in San Francisco, and Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco, were an enormous help to me in writing The White Devil’s Daughters. One of the women she profiled was Tye Leung Schulze, among the first Chinese American woman to exercise the right to vote.

Judy and I were in touch during the five years I spent researching and writing The White Devil’s Daughters, and one of my last email exchanges with her was while I was doing my photo research. She shared some suggestions on how to track down descendants of some of the women who passed through the mission home now known as Cameron House.

She also provided me with one of my favorite photos in the book – a 1912 photo of Tye Leung Schulze behind the wheel of an enormous Studebaker-Flanders. Judy revealed that Tye, a short-statured woman whose nickname was Tiny, never actually learned to drive. I am deeply grateful to her and send my heartfelt condolences to her sister, Susan Lee, and her family.

The post Remembering Judy Yung appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

July 25, 2020

The Queen’s Diaries

It took a decade for The Diaries of Queen Liliuokalani of Hawaii to finally be published. The result: a stunningly beautiful book that will be used by scholars and lovers of Hawaii for years to come.

David W. Forbes led the effort to gather and annotate the diaries of the last queen of Hawaii, aided by the University of Hawaii’s Marvin “Puakea” Nogelmeier, the Hawaii State Archive’s Jason Achiu, and others.

Honololu-based book designer Barbara Pope played a key role as the project’s fierce and tireless advocate. She eventually found a publisher in the Liliuokalani Trust and distribution through the University of Hawaii Press.

I wish The Diaries had been available as I wrote my book Lost Kingdom: The Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure. But it was my good luck that David shared with me more than a decade ago some of the early, primary materials he’d gathered – as well as his painstaking transcriptions and annotations.

I’m grateful for his generosity and happy that we’ve stayed in touch as friends and fellow historians. I profiled David for LitHub last week in a piece titled “The Citizen Scholar Who Led the Hunt for Queen Lili’uokalani’s Lost Diaries.”

You can read the story here. It profiles David and describes his his long journey to explore and document nineteenth century Hawaii.

The post The Queen’s Diaries appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

July 11, 2020

Talking with Min Jin Lee

Over this past week, I’ve been immersed in Pachinko. To be specific, I had the fortunate assignment to read Min Jin Lee’s masterful novel Pachinko, which is a family saga about the world of Koreans living in Japan.

I’ve always loved the sprawling social novels of the 19th century – Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist and Hard Times, Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn.

In the 20th century, perhaps the most famous social novel was John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, which exposed the hardships of migrant farm workers. These are all works that explore pressing social problems through the lives of characters. They’re also sometimes called protest novels, because they often aim to expose a social injustice.

Pachinko is a social novel in that great tradition. Told in the omniscient third person, it follows the lives of four generations of members of a Korean family that emigrated to Japan, facing decades of discrimination and even, in the case of the grandfather of the family, the Presbyterian minister Baek Isak, and his brutal imprisonment.

I loved this novel so much that I didn’t want Pachinko to end. It was rightly chosen as a National Book Award finalist and has earned a place on my living room bookshelf where I keep my favorite books. The fact that I loved it so much made the invitation to be in conversation with its author, Min Jin Lee, even more thrilling.

Our conversation took place Monday, July 13st and was the kick-off event of the Sonoma Valley Authors Festival. I can’t fully express how much fun it was to talk with Min about the writing life, about where she finds her inspiration, and about the very specific challenges she’s faced in making her way through the world as a writer.

Tune in and join us! Here’s the link. And here’s a screenshot of the Zoom conversation between Min and me!

The post Talking with Min Jin Lee appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

The Writing Life

Over this past week, I’ve been immersed in Pachinko. To be specific, I had the fortunate assignment to read Min Jin Lee’s masterful 2017 novel titled Pachinko, which is a family saga about the world of Koreans living in Japan.

I’ve always loved the sprawling social novels of the 19th century – Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist and Hard Times, Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn.

In the 20th century, perhaps the most famous social novel was John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, which exposed the hardships of migrant farm workers. These are all works that explore pressing social problems through the lives of characters. They’re also sometimes called protest novels, because they often aim to expose a social injustice.

Pachinko is a social novel in that great tradition. Told in the omniscient third person, it follows the lives of four generations of members of a Korean family that emigrated to Japan, facing decades of discrimination and even, in the case of the grandfather of the family, the Presbyterian minister Baek Isak, and his brutal imprisonment.

I so loved this novel that I didn’t want Pachinko to end. It rightly was a National Book Award finalist and it’s earned a place on my living room bookshelf where I keep all of my favorite books. The fact that I loved it so much made the invitation to be in conversation with its author, Min Jin Lee, even more thrilling.

Our conversation will be streamed Monday, July 13th, at 9 a.m. PST and 12 pm EST as the very first event of the Sonoma Valley Authors Festival. I can’t fully express how much fun it was to talk with Min about the writing life, about where she finds her inspiration, and about the very specific challenges she’s faced in making her way through the world as a writer.

Tune in and join us! Here’s the link.

The post The Writing Life appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

July 3, 2020

Overcrowded prisons in our back yards

San Quentin State Prison, in San Quentin, Calif., March 13, 2019. (Jim Wilson/The New York Times)

I wrote this essay on San Quentin for a class I’m taking on “Reading and Writing the Very Short Essay.” It’s taught by one of my favorite authors, Lauren Markham.

The essay will run in this Sunday’s Sacramento Bee and other McClatchy papers throughout the state. I’m hoping my former Marin neighbors, Governor Gavin Newsom and Jennifer Siebel Newsom, will read this, too.

***

My Marin County house, perched on a hillside and concealed from the street by redwoods, is five short miles from San Quentin. I’ve driven past the pre-Civil War era prison a thousand times, but never given it much thought. It exists in a world separate from mine.

I used to take the commuter ferry from Larkspur to San Francisco, which passes a few hundred yards from the shore in front of San Quentin. From the boat’s upper deck, I’ve seen prisoners in blue milling around the exercise yard. Did I really see them? Or have I just conjured those men up from prison movies? I’d sip coffee and read the paper, surrounded by other suited workers heading into the city. I’d sometimes wondered if the inmates saw us.

During the winter months, San Quentin juts into the fog-cloaked bay like the prow of a ship, barely visible as the penitentiary and the water merge together. The flickering glimpses of cerulean are the only sign of the thousands of lives unfurling there. The yard is too far to make out individual faces as our ferry accelerates past the tip of land that San Quentin sits on. High fences, concrete overpasses and the rough waters of the Bay separate it from the rest of us.

Ten weeks into the shelter-in-place order, my focus has narrowed to the redwoods standing sentry at my home and the whirring hummingbirds battling for spots at my feeder. I haven’t taken the ferry for months. From my deck, I read about the state’s decision to transfer more than a hundred men, wearing bright orange transit suits, from a prison in Chino. Even before the transfer, San Quentin was overcrowded – with more than 3,500 prisoners crammed into a facility built in the 1850s meant to hold far fewer. There were no cases of Covid at San Quentin before the transfer.

Another three weeks pass. Summer solstice approaches and the county slowly re-opens. With traffic still slow, the shoreline around San Quentin teams with migratory birds. Red-necked Grebes and Black-legged Kittiwakes touch down on nearby marshes. Before the lockdown, windsurfers used the area just to the east of the prison as a place to launch. Kayakers paddle past it on calm days. A new bike path has opened across the San Rafael-Richmond Bridge. One of my sons, who lives in the East Bay, bikes across the span about five times a week. Gov. Gavin Newsom and his family also lived a short drive from the prison, before they moved to Sacramento.

Every night, before settling into the down pillows on my bed, I check on new COVID-19 cases in the county. A few weeks after the transfer, the first infections are detected. Case numbers rise fast. Officials halt visitors and impose a lockdown. To dampen alarm beyond San Quentin’s walls, officials start separating out the prison’s COVID-19 case numbers from the overall count – segregating, at least numerically, our green and prosperous county from California’s oldest prison.

Case numbers climb above 120 and newspapers begin describing the conditions there. Sick prisoners are kept in a part of the prison known as the “adjustment center.” Below them are another set of prisoners, also in barred cells. Droplets containing virus particles float down from above, infecting the people on the next level, according to a chilling report in the San Francisco Chronicle. I can’t get that image out of my head. I picture it as gray fog invisible to the human eye, penetrating the uniforms and then the bodies of the captive men.

I sit outside and look out onto Mount Tamalpais as I write this, gulping in the geranium-scented air as if to prove I still have a sense of smell. Yesterday, I saw a pair of red-tailed hawks making high-pitched cries as they seek to prevent marauding black crows from stealing their eggs. I sit here, in my treetop nest, as the prison heads towards another day of lockdown – a measure imposed soon after the first cases appeared to try to halt the virus. On Sunday, the prison’s case total hits 193. The next day, 337.

I drive past San Quentin as June ends, passing under a Black Lives Matter banner hanging from an overpass. Many of the men who are incarcerated at San Quentin are Black or Latino, while our county is overwhelmingly white. A day or two later, the banner is gone – replaced with banners for summer camps. As of today, the case numbers at the prison have soared to more than 400. As infection spreads, the men at San Quentin now face possible death sentences, even those with short amounts of time left to serve. The case numbers sit in the chart several lines below the overall total – as if the county is trying, through a rearrangement of numbers, to make those infected men disappear.

Over the weekend, protesters in a car caravan called for the early releases of the elderly, the immune-compromised, or those who’ve nearly finished their sentences. San Quentin, often shrouded by early morning fog, is California’s only death row for male prisoners. The state’s decision to move in infected prisoners from elsewhere is handing down a death sentence for even more of them.

A federal judge, reviewing the situation, wiped tears from his eyes.

“We know what’s going to happen,” he said. “We know.”

I leave my placid neighborhood and head towards San Quentin. It’s the first time I’ve tried to go there, even though I grew up in Marin. I’m a reporter and my instincts are to see for myself and ask questions: I am drawn to where this catastrophe is unfolding.

It takes me exactly fifteen minutes to reach the gate from my house. The prison’s COVID-19 case count has jumped from 505 to 832 over the weekend. By Friday morning, it’s 1,345: More than a third of the prison population is infected. Some have been transferred to local hospitals, including one that’s just two miles from my house.

A young guard, masked and about the age of my son, stops me. My own 23-year-old is awaiting the results of his COVID-19 test after several days of fever. I take shallow breaths, as if the air around me is contaminated by a gray fog of virus rolling through the prison gates.

“Can I go in?” I ask.

I know this is an impossible request and I’m not sure why I came, other than a sense of powerlessness about not being able to do anything else. I need to do something, even if it’s only to show up at the gate.

“No,” the young guard answers politely. “With the Covid stuff, it’s all locked up.”

I roll up my windows, take a deep breath, and drive the five miles home.

Julia Flynn Siler is a veteran journalist whose most recent book, “The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown,” is a finalist for a California Book Award.

Editor’s note: This piece has been updated to reflect the latest case count at San Quentin as of Friday.

Read more here: https://www.sacbee.com/opinion/califo...

The post Overcrowded prisons in our back yards appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

July 1, 2020

Honoring Hawaii’s Queen

At a time when statues are toppling across the nation, one work of public art stands tall.

It is the eight-foot-tall bronze of Hawaii’s Queen Lili’uokalani, who faces the state Capitol in Honolulu. This beautifully rendered artwork, by the American realist sculptor Marianna Pineda, is even more powerful today than it was when it was erected in the 1980s.

If anything, this regal public monument become even more beloved over time. To understand why, watch this PBS American Masters short documentary on the Queen that’s just been released. It’s a wonderful and very moving.

Queen Lili’uokalani ruled the independent Kingdom of Hawaii for two years in the last decade of the nineteenth century. In 1893, a group of local businessmen, aided by U.S. Marines, overthrew her. A few years later, the U.S. annexed Hawaii as a territory.

I wrote about the Queen and her overthrow in Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure. I visited the statue many times during my research trips to Honolulu. I was also the historian interviewed for the recent PBS American Masters documentary.

The last time I visited the statue of Queen Lili’uokalani was at opening day of Hawaii’s legislative session in January of 2020. People had draped multiple strands of delicate pink flower lei around the statue’s neck to honor her memory.

Facing the Capitol with her right hand outstretched, the statue seems to say “I surrendered my authority to the United States to avoid bloodshed, but I am with you,” as Richard Rodrigues, community relations specialist in the Hawaii governor’s office, suggests.

In her left hand, the Queen’s statue holds three documents — Hawaii’s Constitution; the Kumulipo, Hawaii’s creation story; and ‘Aloha Oe,’ the most famous of the more than 150 songs and chants that she composed.

It is as if the artist meant the statue to remind today’s legislators that “As you shape Hawaii’s future, remember its history, values and traditions,” Rodrigues adds. The Queen is a powerful and inspiring reminder of the struggles that have shaped our nation. You can watch the PBS documentary here.

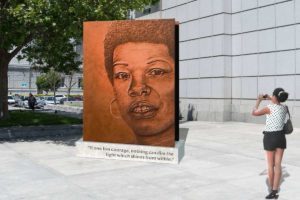

Queen Lili’uokalani, original artwork by Amelie Chabannes for Unladylike2020.

The post Honoring Hawaii’s Queen appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

June 23, 2020

Who Should California Honor?

Father Junipero Serra. Christopher Columbus. Sir Francis Drake. Even Francis Scott Key, who wrote the lyrics to the national anthem.

What do most of the statues being toppled across California have in common?

Mariposa Villaluna at Coit Tower after a crew from the city dismantled a statue of Christopher Columbus during the night. Photo: Paul Chinn / The Chronicle

They’re figures from history who supported white supremacy. And they’re all men.

So here’s a timely proposal. Why don’t we replace them with monuments memorializing the heroic women who’ve helped shape our state? The current protests have given us an opportunity for a deep cultural reckoning about how we want to see ourselves as people. The monuments that any society erects reflect its values. So let’s use this opportunity to address an unjust imbalance. Let’s honor more women, especially women of color.

There are shamefully few statues or monuments honoring California women so far, perhaps because out state’s statue-erectors have historically focused on early conquerors and explorers.

How many of the state’s monuments are dedicated to men versus women? In a list of California’s public statues on Wikipedia, only four out of forty-one are women — or about 10%. Out of the state’s current population of 39 million, just over 50% identify as females.

In San Francisco, widely considered to be one of the most progressive cities in the nation, out of 87 public statues, just two represent real women. The city passed a law about three years ago aimed at increasing the percentage of women honored in this way, but, perhaps predictably, nothing much changed.

A much-anticipated competition to honor the writer Maya Angelou with a piece of public art stalled with a disagreement at City Hall over which representation to pick. One of the competing artists, Lava Thomas, told the San Francisco Chronicle: “Artists deserve better, women deserve better, and Black women deserve better.”

Lava Thomas envisioned this modern design for a Maya Angelou sculpture, but a supervisor wants a traditional approach. Photo by Lava Thomas.

Yes, they do.

At the same time, the few statues of women that do exist are often chosen, not to honor the contribution that those women made as individuals, but because of their physical beauty or their relationships with powerful men.

One of those monuments is a 26-foot-high sculpture of Marilyn Monroe, capturing the moment from the Billy Wilder film, “The Seven Year Itch,” when a blast of air from a subway grate lifts her dress.

Titled Forever Marilyn and created by the artist Seward Johnson, is now in negotiations to be on permanent display in Palm Springs, provoking some discussion of objectification of the actress whose life ended in tragedy.

Likewise, the figure atop a pedestal in San Francisco’s Union Square was meant to represent Nike, the Goddess of Victory, but was modeled on a young Alma de Bretteville, considered a great beauty in her day. Not long after, she became the mistress and eventual wife of the wealthy sugar king Adolph Spreckels.

Instead of sexy movie stars and the paramours of wealthy men, perhaps we should start honoring California women who directed films, worked for social justice, and led a civil rights movement.

I can suggest a few possibilities. Bridget “Biddy” Mason, an African American woman born into slavery, she bought her freedom, became a successful investor, and helped found Los Angeles’s First African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Or Julia Morgan, the first woman to become a licensed architect in the state who helped erect some of California’s greatest architectural treasures.

Perhaps we should consider Tien Fuh Wu, a child servant at a brothel who’d been sold by her father, she eventually became a pioneering social worker in San Francisco who worked tirelessly for decades to help vulnerable girls and women in Chinatown.

We might even consider a living woman — Dolores Huerta – the 90-year-old civil rights worker and activist who, helped found the organization that would become the United Farmworkers and organize the Delano grape strike in 1965.

Tye Leung Schulze, courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library

For more inspiring choices, you may want to join an online event June 30th co-hosted by the California Historical Society, Cal Humanities, and KQED, for a viewing and discussion of three short documentaries on women who changed California’s history.

One of the women I wrote about in The White Devil’s Daughters, Tye Leung Schulze, is the subject of one of the documentaries. She was an early advocate for trafficked women. I’m interviewed in the documentary about her life, as is her grandson, Ted Schulze.

The other two women highlighted in the documentary shorts are Lois Weber, the first woman to direct a feature-length film, and Charlotta Spears Bass, a newspaper editor, Civil Rights crusader, and the first African American woman to be nominated for Vice President.

It’s about time we start looking for other heroes to look up to. And they shouldn’t all be men. As Huerta might say, Si, se puede!

The post Who Should California Honor? appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.