Julia Flynn Siler's Blog, page 6

February 18, 2019

Debunking the “White Rescue Myth”

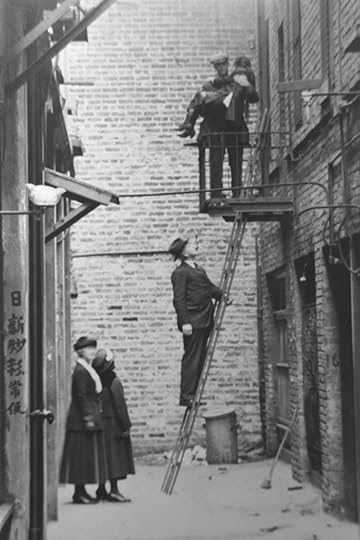

The best-known image of the pioneering anti-trafficking crusader Donaldina Cameron at work was taken in the early 20th century in a garbage-strewn alley in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Cameron, wearing a full black skirt that fell just above her ankles and a dowdy, small- brimmed hat, gazes toward the camera. A man in a suit stands partway up a ladder propped against a brick building. On a balcony above him, a man who appears to be a plainclothes police officer holds a girl in his arms. She has a long black braid hanging down her back and is the “slave girl” supposedly being rescued.

Donaldina Cameron (left, standing) with interpreter and police officers staging a rescue of a Chinese girl. Courtesy of Cameron House.

We don’t know who the photographer was or why the photograph was taken.

We do know that staging of photographs was the norm for most turn-of-the–century photography and the image was probably taken to accompany one of the many newspaper articles about Cameron’s rescue work at that time.

But this photograph has become a visual embodiment of what some scholars call “the white rescue myth.”

Cameron, and the women who came before her who founded and supported the Presbyterian Mission House, were white. They described what they did as “rescue work.” Their goal was to protect, educate, and convert vulnerable girls and women. And most of those girls and women were Chinese (although Japanese, Syrian, and other nationalities of women also took refuge at the home.)

In the years I spent researching and writing about the individual lives of women who lived and worked at the rescue home at 920 Sacramento Street, I learned that many, if not most, of them were not “rescued” by policemen on ladders or missionaries breaking into brothels, especially in the later years of the home.

Many, if not most, arrived there through their own volition. They sought out and then chose to live at the home, at least for a while.

The White Devil’s Daughters documents a remarkable, collective story of women helping other women and reaching across divides of race and class to do so. Cameron and the other white mission workers not only relied mightily on the Chinese residents-turned-aides in the home: they simply could not have done their jobs without them.

The most important stories I found were those of the girls and women who escaped sex slavery to find their freedom. I also discovered that some of the home’s Asian residents chose to continue the fight against slavery by working as translators in court and among immigration officials and in running the home on a day-to-day basis. They, too, decided to take part in the ongoing fight against slavery.

What’s generally overlooked in this photograph of Cameron at work is that she’s standing next to another woman – possibly the interpreter Ida Lee, one of the many Chinese women who worked closely alongside her over the years. Look closely: this iconic photograph of “rescue work” tells a very different story than one might expect.

The post Debunking the “White Rescue Myth” appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

January 24, 2019

The Fight to End Modern Slavery

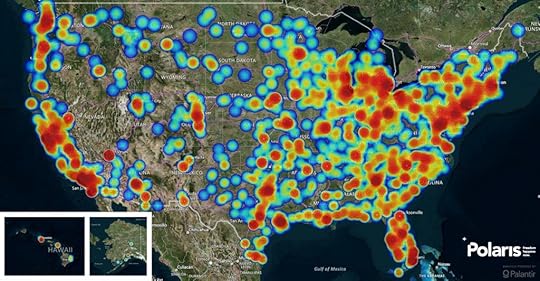

January is Human Trafficking Prevention Month, a designation of heartbreaking relevance to my home state of California. Not only does it remain one of the nation’s leading hubs for sex and labor trafficking; the state is also home to a host of non-profit organizations who fight the crimes of sex and labor slavery year-round.

Map showing locations of human trafficking cases in 2017, as tracked by anti-trafficking organization Polaris.

What’s not so well known is that while the Golden State has long been a hub for this crime, it’s also pioneered efforts to combat it, with a long history of fighting the exploitation of girls and women. The San Francisco Bay Area in particular played an historic role in one of the earliest anti-trafficking efforts in the country.

Nearly a hundred and fifty years ago, a group led by women decided to set up a refuge in San Francisco for girls and young women who’d been trafficked from China and elsewhere. Calling it slavery, they went on to raise the profile of human trafficking, attracting news coverage, testifying in front of legislators, and helping to bring about an early anti-trafficking law.

Their crusade started in the 1870s when the women bought a house on the edge of San Francisco’s Chinatown. First called the Occidental Board’s Presbyterian Mission House, the structure was destroyed during the 1906 earthquake and fire. Rebuilt, it stands in the same spot on Sacramento Street today. It is now known as Cameron House, named after its long-serving superintendent, Donaldina Cameron. The organization is primarily a social services agency, but it still occasionally helps trafficking survivors.

From the 1870s to the 1930s, thousands of girls and young women passed through the home’s doors and found their freedom. Cameron and her many Chinese colleagues at the home helped draw public attention to the issue of girls and women being forced into labor or sex slavery along the West Coast, from Vancouver to San Diego.

The stories of the women who fought and escaped slavery at the turn of the twentieth century is the subject of my new book, The White Devil’s Daughters, which will be published on May 16th by Alfred A. Knopf.

Today, organizations such as the Bay Area Anti-Trafficking Coalition, Not for Sale, The Freedom Story, the Law Foundation of Silicon Valley, the Pacific Links Foundation, the Coalition to Abolish Slavery & Trafficking (CAST) and Saving Innocence carry on Donaldina Cameron’s fight against trafficking. These leading non-profits in today’s fight against human trafficking are the heirs to Victorian-era women in shirtwaists and corsets, who began waging this battle long ago.

The post The Fight to End Modern Slavery appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

December 19, 2018

The Cameron Family’s Gift to the Bancroft Library

One morning, in June of 2016, an e-mail popped into my inbox from the grandniece of Donaldina Cameron, one of the main characters in The White Devil’s Daughters, my nonfiction account of the women who fought slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

I’d already been researching and writing my book for more than three years by that time. Ann Cameron’s email said that while cleaning out her brother’s home for a move, she’d discovered a box filled with photos, letters, and other genealogical material about her great aunt Dolly, as Donaldina was known.

Cameron family materials dating to the 1840s Family

In her funny, understated way, Ann wrote “There is lots of genealogy stuff by lots of folks…letters from and to Dolly, a dead pheasant from a special hat…several Bibles…family photo albums from Scotland…Not sure how useful any of this stuff is at this stage by am happy to have you paw through it if you like…”

Did I ever! I called her within minutes of getting her note and arranged to come the next day to her home to look through the box. I was excited by the prospect: I’d already scoured the Bancroft Library’s massive collections for material on Cameron, as well as Cameron House in Chinatown’s private files, and Stanford University’s special collections.

Finding primary material like this is every researcher’s dream. Dolly Cameron has had three biographies written about her already and this newly discovered cache offered the prospect of finding out something new about her. I rushed over to meet Ann at her home and she kindly insisted I take a box of materials home with me. Some of it dated to the 1840s.

Ann had loaned me this treasure trove of new material for my book. Two years later, after finishing the final edits of the manuscript, I reached out to her and her sister Catherine, a professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado at Boulder. I asked whether they might consider donating the material to the Bancroft Library at U.C. Berkeley, the preeminent repository of materials relating to the American West.

To my delight, the Cameron sisters decided to gift the box of family materials to this great library and Theresa Ann Salazar, the curator of the Bancroft’s Western Americana collection, was happy to accept it as a natural addition to the library’s Presbyterian Church in Chinatown collection.

So, in early December, I hopped in my car, drove over the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge to Berkeley, and handed off a crate of photographs, correspondence, family Bibles, and other materials. It was an early holiday gift from the Cameron family to the many authors, historians, and students who regularly use the Bancroft Library.

Julia Flynn Siler is a New York Times best-selling author. Her new book, The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Against Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown, is forthcoming from Alfred A. Knopf in May of 2019. For more information, please visit www.juliaflynnsiler.com

Author Julia Flynn Siler delivering materials to the Bancroft

Acquisitions Assistant Rachel Lee accepting the Cameron family’s materials at the Bancroft Library

The post The Cameron Family’s Gift to the Bancroft Library appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

July 18, 2018

Finding Your Literary Community

At this year’s annual gathering of the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley, I was honored to give the opening talk. Here are my remarks.

***

I’m so happy to be here… to help celebrate the rollicking and generous spirit that has infused our Community all these years.

Julia Flynn Siler

How many first-timers are here today? Raise your hands…

Well, for you newbies, you’ll see what I mean about community spirit here during the Follies later in the week. Or you may discover it while connecting with other writers over dinner or while hiking on Thursday with your fellow work-shoppers.

I have vivid memories of how I felt my first time.

I’d been a newspaper and magazine journalist for decades….and I felt way out of my comfort zone with so all these fiction writers. The workshop leaders and notable alumnae at Squaw that year, at least on paper, seemed like an intimidating bunch. Amy Tan, Jim Houston, and Annie Lamott were all there my first week.

I remember rooming with a much younger writer from L.A. – someone who was writing fiction involving cyber-sex, as I recall. I can only guess what she thought about getting stuck with a Wall Street Journal reporter. While my roommate spent every night partying with other writers, I was a mom reading my manuscripts in the evenings, missing the five and seven-year-old boys I’d left at home.

View of the Squaw Valley

But, for me, the most lasting gift of that first summer was finding my community. For many years, I’ve come to the valley: first as a participant in the non-fiction workshop, then as a staffer and, eventually, as a board member… I’ve discovered a group of people from different places and life circumstances who have one thing in common…

… a love of and dedication to the art of storytelling. And a belief that carefully crafted words matter. The famous writers among us and the newbies all have at least one thing in common – we’re here together struggling over the craft of how to best put words to paper.

Now, some of those same people I spent a week with fifteen years ago have become some of my closest and most trusted friends. Through three books and many articles, the nonfiction author and staff member Frances Dinkelspiel has been my first reader…

…and the nonfiction writing group in San Francisco she invited me to join after we met at Squaw, North 24th Writers, has become my life raft, helping me develop my craft. This has been especially valuable to me lately. Many of us are struggling to stay afloat in a world where we’re being told, over and over, that our work as storytellers doesn’t matter.

Staff, board members, and friends

Since our work as writers is mostly solitary, the question many of us are grappling with is how to summon up the concentration required to produce deep and honest writing, especially a time when politics is so depressing and scary. How do we keep going…?

Well, I’m going to make the case for finding and building a writing community…

The way I’ve tried to do it is by reaching out to other writers for support and encouragement – the antidote to standing by myself at my writing desk every day and living in my own head so much, usually in the nineteenth century!

I work best in the morning so you’ll find me at my desk from about eight until noon each day. When I’m deep into a project, I’ll start the day by meditating – I use one of the meditation apps – and I force myself to ignore the news and email until after I’ve gotten my writing done.

After that, I turn outward: I take walks with friends and spend a lot of time in the afternoons doing research in libraries and attending bookstore readings. I try my best to show up for the readings of friends I’ve met here and in other parts of the writing community.

The novelist Karen Joy Fowler

That’s one of the reasons I’m so grateful for the friends I’ve made here – and for the wider literary community that is thriving in California, thanks to so many grassroots organizations like the Community of Writers and California’s great community colleges and university system.

Up and down the state, tiny workshops and reading series take place up that connect writers and readers. At libraries and gatherings like this one that offer platforms to women, to writers of color, to older people, and to LGBTQ people. That’s a quiet, but very powerful form of resistance – a way to come together and value each other by listening.

I’d like to tell you a story about how the Community of Writers offered a welcome to someone who lived on the margins of society. To me, this is a story about embracing difference and generosity of spirit – qualities I hope you’ll experience this week.

His name was Paul Radin. Old-timers might remember his dramatic entrance one summer to our annual gathering when he arrived on horseback, wearing his flat-brimmed hat and western boots.

He lived on a property his family owned on the Truckee River, close to nature and to Squaw Valley, and, although he was born in Boston to a Jewish family, he immersed himself in Native American culture, often attending pow-wows.

Paul was an outsider who found support and friendship at the Community of Writers, particularly from the novelist Louis B. Jones and the radio host and editor Andrew Tonkovich. Late in his life, a bear moved into Paul’s cabin, pushing Paul out into the woods. If he wanted to go into the cabin to get something, say a book of poetry or a cooking pot, he would blast his air-horn to scare the bear out – long enough, at least, for him to retrieve whatever he was looking for.

The novelist Louis B. Jones

Paul was shy and generally mistrustful of most people, but he welcomed Louis and Andrew, particularly when they brought him gifts to ease the pain of his cancer towards the end of his life. Before he got too sick, he’d come to the Community of Writers gatherings, and sometimes reading his shamanistic poetry on the night of the follies.

Please remember Paul’s whimsical spirit and his family’s kind donation to honor him and the Community when you look at the Dream Wagon, our tiny house on wheels. Like so much at the Community of Writers, it was born out of a spirit of generosity. It’s handmade. It’s a little quirky – made from redwood beams that were salvaged from beneath someone’s porch.

Poke your head into the “Dream Wagon” sometime this week and browse through some of the books by staffers and alumnae. When you’re there, maybe think of the spirit of our annual gatherings for nearly half a century: the way that different people travel from all over the state and the country to spend week together as a creative community. The spirit of Squaw reflects the kind of inclusiveness that welcomed Paul.

I truly hope you I have as good and life-changing an experience at Squaw this week as I have had. You are now part of a community that has played a role in nurturing some of the most significant writers and voices to come out of America…and we’ll be marking our half century beginning next year.

One of the things we’re doing to mark that half century is an oral history project, to make sure we record the memories of some of the earliest participants in the Community.

The novelist Richard Ford, who’s best known for The Sportswiter and Independence Day, for example, first attended in the early 1970s. He’d been a student of the Community’s co-founder, Oakley Hall, at U.C. Irvine and, at Squaw, he was in a workshop led by the Paris Review co-founder Peter Matthiessen, the author of The Snow Leopard.

Richard Ford then returned to Squaw as a staffer and, one year, sat out on the deck in the sun with a young Amy Tan, discussing her first short story. When Amy first arrived, she was a technical writer, working 90 hours a week, and had never been published as a creative writer. Her experience at Squaw helped give her the confidence to weave together the stories she’d been writing about mothers, daughters, and the immigrant experience.

The next time Richard Ford came across Amy’s story they’d discussed outdoors that summer, Amy had woven it into her book, The Joy Luck Club which became a bestselling novel and a movie.

Amy Tan reading from “Where The Past Begins”

That’s the spirit of the Community: writers helping other writers do their best work. Some have published books that have become bestsellers while others have only shown our stories to friends…

…but we all grapple with words and how to get them right. And that’s the focus of this week.

The history of the Community of Writers began just like that: with good friends coming together. Starting in the late sixties, the novelists Oakley Hall and Blair Fuller, who were both living in the valley at the time, decided to invite their writing pals and students up to Squaw to spend a week in the summer workshopping their writing.

Behind the scenes, there were people who quietly made these often-raucous gatherings possible. From the very beginning, Barbara Hall worked alongside her husband Oakley on the workshops, so did Diana Fuller, who was then married to Blair – checking people in, spreading out the pastel tablecloths that are still used today, and doing some of the cooking.

Diana co-founded and ran the screenwriting program for many years, and Barbara, in turn, brought her gifts as a photographer to the portraits she took of Peter Matthiessen, the poet Galway Kinnell, the screenwriter Gill Dennis, Robert Stone and many others that you’ll see hanging on the walls near the office.

This is the first year Barbara won’t be at Squaw – she died in early June. Luckily, she helped guide her youngest daughter, Brett, who is now the Community’s executive director, into that role.

Let’s take a moment to think of Barbara….

…and send our deepest condolences to her daughters Brett, Sands, and Tracy, who took such loving care of their mother in her old age.

A group of closely-knit families – the Halls, the Fullers, the Ancinas’s, the Joneses, the Klaussens, the Alvarez/Tonkovich’s, and the Millers, the Naifys, have created the environment for you to connect with other writers. This is your chance to listen carefully to how they respond to your work, and show the same care and generosity to them that they’ve shown you.

The “Unreliable Narrators” at the Follies

I’ll warn you now: it can be a hard week, particularly if you’ve never had your work critiqued before in a workshop.

For me, my first summer here was kind of like that Warren Zevon song that Linda Ronstadt made famous: Let me play it for you…

“Poor Poor Pitiful Me”. Remember the line about “being worked over good” by the guy from Hollywood who….

“Put me through some changes Lord

Sort of like a Waring blender”

That’s pretty much how I felt after my first workshop week: not exactly like a smoothie, but close.

Workshop #9 members at the Follies (led by Jack Boulware)

I had a lot to think about when I got home based on my fellow workshopper’s comments. While some of the criticism was hard to take, it was valuable afterwards. And, like most of us, I never fully absorbed the praise the piece also got during workshop….

Then, about nine months later, I wrote a story for the Wall Street Journal that caused quite a commotion. A publisher emailed me to ask if I’d consider writing a book based upon the story.

I had no idea who that publisher was – as it turned out, he was kind of a big deal – but I DID know a literary agent – and that was Michael Carlisle, who runs the nonfiction program. He took me on as a client and negotiated a very good book contract for me.

By the time I arrived at Squaw the following year, in 2004, I had the prologue of what would become my first book, The House of Mondavi, to submit to our workshop.

And here’s the incredible thing. One of the leaders of the nonfiction workshop that year, Moira Johnston Block, agreed to become my mentor for that first book – reading every single chapter and helping me to learn how to break some of the bad habits I’d picked up as a long-time journalist – like using too many quotes. Most importantly, she taught me how to write in scene.

Again, I was part of a continuum at Squaw…. a much more accomplished writer – Moira had written seven nonfiction books at that point — took me under her wing and guided me as I wrote my first book.

Now, as a workshop leader myself, it’s my turn to help other writers tell their stories.

So, here’s my advice to you on that scary morning when your piece is being workshopped.

*Bring a notebook and pen and spend that time listening to the comments.

*Try not to say much and don’t waste your breath defending your work. Just listen.

*When your session is done, put the piece and your notes away for a week, or two, or even three before coming back to it with a fresh eye.

Just as importantly, be on the look-out during the week for people in your workshop whose comments are particularly helpful to you. They’re the people you’ll want to connect with after the week is over. They could become your first readers – and you may want to start a writing group of your own.

Unlike other writing conferences, this week at Squaw is more about the work – the words, the writing, and the stories – than about the marketing.

Yes, there are editors and agents here too: some of your work will catch their attention. But their primary goals – at least for this week – are for the feedback to take place that will help you push your work to the next level.

While some of you are new to the writing world, others of you have been doing it for a very long time. A number of the readers in this year’s published alumni readings were first at Squaw in the 1990s – proof of just long it can take for a good book to gestate. All of us – no matter where we are on the continuum – can get better.

For me, the deeper message of my experience of Squaw, and of spending the time together in this high-altitude setting — is that the work we’re doing as storytellers IS valuable.

Our words matter and our stories matter. They help us build empathy by looking through someone else’s eyes. As Dave Eggers wrote in the Times about a week ago, writing and other forms of art expands our “moral imagination and makes it impossible to accept the dehumanization of others.”

We can help each other learn how to make our stories even more effective in delivering that gut punch or eliciting the tears we’re hoping to bring to your readers’ eyes, or whatever your goal may be.

Our community is committed to the idea that reading and writing stories are portals to enter the world of someone different than ourselves. A way to open us up to the experience of the other – and to help close the yawning empathy gap which seems, increasingly, to divide us from each other.

That’s my goal with the nonfiction I write – to close the empathy gap. I focus on little-known stories from history. It was a natural evolution from the reporting I’d done for so long.

My first book was a hybrid of journalism and narrative history: in it, I told the true story of four generations of a Napa Valley wine family and their struggles over a billion-dollar family business. Part family saga and part Shakespearean tragedy, it was called The House of Mondavi: The Rise and Fall of an American Wine Dynasty.

My second book was titled Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, The Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure. It was about Hawaii’s last monarch and her overthrow – a profoundly sad story that also explores family dynamics and lost fortunes set in the late nineteenth century.

For the last several years, I’ve again returned to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The book I’m working on, The White Devil’s Daughters, centers around a mission home in San Francisco’s Chinatown where thousands of Chinese girls and women found refuge from sex slavery and other forms of servitude.

As the girls and women we see in the news today, they were caged and separated from their families.

I based the narrative on tens of thousands of pages of documents from the National Archives and elsewhere. It’s also a work of investigative history, in the sense that I’m aiming to tell the stories of people who, for the most part, left only the faintest trace in the historical record.

The story starts in the 1870s, when the rabble-rouser Denis Kearney were shouting “The Chinese Must Go” and a California gubernatorial candidate, James Phelan, ran on the slogan “Keep California White!”

That racism against the Chinese took hold across the state and legislators, in 1882, passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which remained a law until it was repealed in the 1940s.

During that period of brutal racism, there was a small group of people who became allies to the Chinese sex slaves. I wanted to learn how and why those people who became their allies could bridge that empathy gap – to take the risks to protest on behalf of people whom many their fellow white-citizens didn’t even consider fully human. They were pioneers in the movement to fight sex slavery and human trafficking of Chinese women and girls.

And, in turn, how did these girls and women – facing the most extreme forms of brutality and confinement – gain their freedom?

The story is a dark corner of American history, but one that I think has resonance today. It’s coming out next May. My editor at Knopf, Ann Close, is a longtime Squaw faculty member. Likewise, my literary agent for all three of my books has been Michael Carlisle.

So, I guess I’m up here today because my story of connecting with other people at Squaw is an unusually fortunate one. I was lucky to find Michael, and my editor Ann, who was also Jim Houston and Oakley Hall’s editor: I feel proud to be part of that continuum.

Connecting with other writers and joining the continuum is a big benefit of being part of the Community of Writers.

But I don’t think nabbing an agent or an editor should be your main goal this week. I’d urge you, instead, to focus on the work and on building friendships with other writers. Our community is a special one because we emphasize the work – and on collaboration to make it better – rather than on the business side of publishing.

On a day-to-day basis, it was my greatest stroke of good fortune to have made friends with some of the people in that first workshop, who then went on to support me as I made the transition from journalist to author…

They’re the ones – the eight women in my workshop North 24th – who’ve seen me at my worst and my best over the years. They’re the ones, in the words of Annie Lamott, who’ve read all of my shitty first drafts…

…our workshop has been together for more than twenty years. I’m a relative newcomer to it having joined fifteen years ago. I count my blessings every day to have been invited to join them by my fellow workshopper Frances all those years ago. In fact, they workshopped this talk before I dared make it.

So, for those of you who are new to Squaw, here are my last words of

advice:

Read closely.

Try to read each piece twice, if you can – the first time without marking it up.

Be generous.

Get enough sleep.

Make friends with your favorite readers after workshop week ends….

And…remember… that one drink will hit you like two or three at high altitude!

The post Finding Your Literary Community appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

Building a Vibrant Literary Community

At this year’s annual gather of the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley, I was honored to give the opening talk. Here are my remarks about the gathering that has meant so much to me and to many other writers over the years. This year’s Writers Workshop ran from July 8-15, 2018.

***

I’m so happy to be here… to help celebrate the rollicking and generous spirit that has infused our Community all these years.

Julia Flynn Siler

How many first-timers are here today? Raise your hands…

Well, for you newbies, you’ll see what I mean about community spirit here during the Follies later in the week. Or you may discover it while connecting with other writers over dinner or while hiking on Thursday with your fellow work-shoppers.

I have vivid memories of how I felt my first time.

I’d been a newspaper and magazine journalist for decades….and I felt way out of my comfort zone with so all these fiction writers. The workshop leaders and notable alumnae at Squaw that year, at least on paper, seemed like an intimidating bunch. Amy Tan, Jim Houston, and Annie Lamott were all there my first week.

I remember rooming with a much younger writer from L.A. – someone who was writing fiction involving cyber-sex, as I recall. I can only guess what she thought about getting stuck with a Wall Street Journal reporter. While my roommate spent every night partying with other writers, I was a mom reading my manuscripts in the evenings, missing the five and seven-year-old boys I’d left at home.

View of the Squaw Valley

But, for me, the most lasting gift of that first summer was finding my community. For many years, I’ve come to the valley: first as a participant in the non-fiction workshop, then as a staffer and, eventually, as a board member… I’ve discovered a group of people from different places and life circumstances who have one thing in common…

… a love of and dedication to the art of storytelling. And a belief that carefully crafted words matter. The famous writers among us and the newbies all have at least one thing in common – we’re here together struggling over the craft of how to best put words to paper.

Now, some of those same people I spent a week with fifteen years ago have become some of my closest and most trusted friends. Through three books and many articles, the nonfiction author and staff member Frances Dinkelspiel has been my first reader…

…and the nonfiction writing group in San Francisco she invited me to join after we met at Squaw, North 24th Writers, has become my life raft, helping me develop my craft. This has been especially valuable to me lately. Many of us are struggling to stay afloat in a world where we’re being told, over and over, that our work as storytellers doesn’t matter.

Staff, board members, and friends

Since our work as writers is mostly solitary, the question many of us are grappling with is how to summon up the concentration required to produce deep and honest writing, especially a time when politics is so depressing and scary. How do we keep going…?

Well, I’m going to make the case for finding and building a writing community…

The way I’ve tried to do it is by reaching out to other writers for support and encouragement – the antidote to standing by myself at my writing desk every day and living in my own head so much, usually in the nineteenth century!

I work best in the morning so you’ll find me at my desk from about eight until noon each day. When I’m deep into a project, I’ll start the day by meditating – I use one of the meditation apps – and I force myself to ignore the news and email until after I’ve gotten my writing done.

After that, I turn outward: I take walks with friends and spend a lot of time in the afternoons doing research in libraries and attending bookstore readings. I try my best to show up for the readings of friends I’ve met here and in other parts of the writing community.

The novelist Karen Joy Fowler

That’s one of the reasons I’m so grateful for the friends I’ve made here – and for the wider literary community that is thriving in California, thanks to so many grassroots organizations like the Community of Writers and California’s great community colleges and university system.

Up and down the state, tiny workshops and reading series take place up that connect writers and readers. At libraries and gatherings like this one that offer platforms to women, to writers of color, to older people, and to LGBTQ people. That’s a quiet, but very powerful form of resistance – a way to come together and value each other by listening.

I’d like to tell you a story about how the Community of Writers offered a welcome to someone who lived on the margins of society. To me, this is a story about embracing difference and generosity of spirit – qualities I hope you’ll experience this week.

His name was Paul Radin. Old-timers might remember his dramatic entrance one summer to our annual gathering when he arrived on horseback, wearing his flat-brimmed hat and western boots.

He lived on a property his family owned on the Truckee River, close to nature and to Squaw Valley, and, although he was born in Boston to a Jewish family, he immersed himself in Native American culture, often attending pow-wows.

Paul was an outsider who found support and friendship at the Community of Writers, particularly from the novelist Louis B. Jones and the radio host and editor Andrew Tonkovich. Late in his life, a bear moved into Paul’s cabin, pushing Paul out into the woods. If he wanted to go into the cabin to get something, say a book of poetry or a cooking pot, he would blast his air-horn to scare the bear out – long enough, at least, for him to retrieve whatever he was looking for.

The novelist Louis B. Jones

Paul was shy and generally mistrustful of most people, but he welcomed Louis and Andrew, particularly when they brought him gifts to ease the pain of his cancer towards the end of his life. Before he got too sick, he’d come to the Community of Writers gatherings, and sometimes reading his shamanistic poetry on the night of the follies.

Please remember Paul’s whimsical spirit and his family’s kind donation to honor him and the Community when you look at the Dream Wagon, our tiny house on wheels. Like so much at the Community of Writers, it was born out of a spirit of generosity. It’s handmade. It’s a little quirky – made from redwood beams that were salvaged from beneath someone’s porch.

Poke your head into the “Dream Wagon” sometime this week and browse through some of the books by staffers and alumnae. When you’re there, maybe think of the spirit of our annual gatherings for nearly half a century: the way that different people travel from all over the state and the country to spend week together as a creative community. The spirit of Squaw reflects the kind of inclusiveness that welcomed Paul.

I truly hope you I have as good and life-changing an experience at Squaw this week as I have had. You are now part of a community that has played a role in nurturing some of the most significant writers and voices to come out of America…and we’ll be marking our half century beginning next year.

One of the things we’re doing to mark that half century is an oral history project, to make sure we record the memories of some of the earliest participants in the Community.

The novelist Richard Ford, who’s best known for The Sportswiter and Independence Day, for example, first attended in the early 1970s. He’d been a student of the Community’s co-founder, Oakley Hall, at U.C. Irvine and, at Squaw, he was in a workshop led by the Paris Review co-founder Peter Matthiessen, the author of The Snow Leopard.

Richard Ford then returned to Squaw as a staffer and, one year, sat out on the deck in the sun with a young Amy Tan, discussing her first short story. When Amy first arrived, she was a technical writer, working 90 hours a week, and had never been published as a creative writer. Her experience at Squaw helped give her the confidence to weave together the stories she’d been writing about mothers, daughters, and the immigrant experience.

The next time Richard Ford came across Amy’s story they’d discussed outdoors that summer, Amy had woven it into her book, The Joy Luck Club which became a bestselling novel and a movie.

Amy Tan reading from “Where The Past Begins”

That’s the spirit of the Community: writers helping other writers do their best work. Some have published books that have become bestsellers while others have only shown our stories to friends…

…but we all grapple with words and how to get them right. And that’s the focus of this week.

The history of the Community of Writers began just like that: with good friends coming together. Starting in the late sixties, the novelists Oakley Hall and Blair Fuller, who were both living in the valley at the time, decided to invite their writing pals and students up to Squaw to spend a week in the summer workshopping their writing.

Behind the scenes, there were people who quietly made these often-raucous gatherings possible. From the very beginning, Barbara Hall worked alongside her husband Oakley on the workshops, so did Diana Fuller, who was then married to Blair – checking people in, spreading out the pastel tablecloths that are still used today, and doing some of the cooking.

Diana co-founded and ran the screenwriting program for many years, and Barbara, in turn, brought her gifts as a photographer to the portraits she took of Peter Matthiessen, the poet Galway Kinnell, the screenwriter Gill Dennis, Robert Stone and many others that you’ll see hanging on the walls near the office.

This is the first year Barbara won’t be at Squaw – she died in early June. Luckily, she helped guide her youngest daughter, Brett, who is now the Community’s executive director, into that role.

Let’s take a moment to think of Barbara….

…and send our deepest condolences to her daughters Brett, Sands, and Tracy, who took such loving care of their mother in her old age.

A group of closely-knit families – the Halls, the Fullers, the Ancinas’s, the Joneses, the Klaussens, the Alvarez/Tonkovich’s, and the Millers, have created the environment for you to connect with other writers. This is your chance to listen carefully to how they respond to your work, and show the same care and generosity to them that they’ve shown you.

I’ll warn you now: it can be a hard week, particularly if you’ve never had your work critiqued before in a workshop.

For me, my first summer here was kind of like that Warren Zevon song that Linda Ronstadt made famous: Let me play it for you…

“Poor Poor Pitiful Me”. Remember the line about “being worked over good” by the guy from Hollywood who….

“Put me through some changes Lord

Sort of like a Waring blender”

That’s pretty much how I felt after my first workshop week: not exactly like a smoothie, but close.

Workshop #9 members at the Follies (led by Jack Boulware)

I had a lot to think about when I got home based on my fellow workshopper’s comments. While some of the criticism was hard to take, it was valuable afterwards. And, like most of us, I never fully absorbed the praise the piece also got during workshop….

Then, about nine months later, I wrote a story for the Wall Street Journal that caused quite a commotion. A publisher emailed me to ask if I’d consider writing a book based upon the story.

I had no idea who that publisher was – as it turned out, he was kind of a big deal – but I DID know a literary agent – and that was Michael Carlisle, who runs the nonfiction program. He took me on as a client and negotiated a very good book contract for me.

By the time I arrived at Squaw the following year, in 2004, I had the prologue of what would become my first book, The House of Mondavi, to submit to our workshop.

And here’s the incredible thing. One of the leaders of the nonfiction workshop that year, Moira Johnston Block, agreed to become my mentor for that first book – reading every single chapter and helping me to learn how to break some of the bad habits I’d picked up as a long-time journalist – like using too many quotes. Most importantly, she taught me how to write in scene.

Again, I was part of a continuum at Squaw…. a much more accomplished writer – Moira had written seven nonfiction books at that point — took me under her wing and guided me as I wrote my first book.

Now, as a workshop leader myself, it’s my turn to help other writers tell their stories.

So, here’s my advice to you on that scary morning when your piece is being workshopped.

*Bring a notebook and pen and spend that time listening to the comments.

*Try not to say much and don’t waste your breath defending your work. Just listen.

*When your session is done, put the piece and your notes away for a week, or two, or even three before coming back to it with a fresh eye.

Just as importantly, be on the look-out during the week for people in your workshop whose comments are particularly helpful to you. They’re the people you’ll want to connect with after the week is over. They could become your first readers – and you may want to start a writing group of your own.

Unlike other writing conferences, this week at Squaw is more about the work – the words, the writing, and the stories – than about the marketing.

Yes, there are editors and agents here too: some of your work will catch their attention. But their primary goals – at least for this week – are for the feedback to take place that will help you push your work to the next level.

While some of you are new to the writing world, others of you have been doing it for a very long time. A number of the readers in this year’s published alumni readings were first at Squaw in the 1990s – proof of just long it can take for a good book to gestate. All of us – no matter where we are on the continuum – can get better.

For me, the deeper message of my experience of Squaw, and of spending the time together in this high-altitude setting — is that the work we’re doing as storytellers IS valuable.

Our words matter and our stories matter. They help us build empathy by looking through someone else’s eyes. As Dave Eggers wrote in the Times about a week ago, writing and other forms of art expands our “moral imagination and makes it impossible to accept the dehumanization of others.”

We can help each other learn how to make our stories even more effective in delivering that gut punch or eliciting the tears we’re hoping to bring to your readers’ eyes, or whatever your goal may be.

Our community is committed to the idea that reading and writing stories are portals to enter the world of someone different than ourselves. A way to open us up to the experience of the other – and to help close the yawning empathy gap which seems, increasingly, to divide us from each other.

That’s my goal with the nonfiction I write – to close the empathy gap. I focus on little-known stories from history. It was a natural evolution from the reporting I’d done for so long.

My first book was a hybrid of journalism and narrative history: in it, I told the true story of four generations of a Napa Valley wine family and their struggles over a billion-dollar family business. Part family saga and part Shakespearean tragedy, it was called The House of Mondavi: The Rise and Fall of an American Wine Dynasty.

My second book was titled Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, The Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure. It was about Hawaii’s last monarch and her overthrow – a profoundly sad story that also explores family dynamics and lost fortunes set in the late nineteenth century.

For the last several years, I’ve again returned to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The book I’m working on, The White Devil’s Daughters, centers around a mission home in San Francisco’s Chinatown where thousands of Chinese girls and women found refuge from sex slavery and other forms of servitude.

As the girls and women we see in the news today, they were caged and separated from their families.

I based the narrative on tens of thousands of pages of documents from the National Archives and elsewhere. It’s also a work of investigative history, in the sense that I’m aiming to tell the stories of people who, for the most part, left only the faintest trace in the historical record.

The story starts in the 1870s, when the rabble-rouser Denis Kearney were shouting “The Chinese Must Go” and a California gubernatorial candidate, James Phelan, ran on the slogan “Keep California White!”

That racism against the Chinese took hold across the state and legislators, in 1882, passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which remained a law until it was repealed in the 1940s.

During that period of brutal racism, there was a small group of people who became allies to the Chinese sex slaves. I wanted to learn how and why those people who became their allies could bridge that empathy gap – to take the risks to protest on behalf of people whom many their fellow white-citizens didn’t even consider fully human. They were pioneers in the movement to fight sex slavery and human trafficking of Chinese women and girls.

And, in turn, how did these girls and women – facing the most extreme forms of brutality and confinement – gain their freedom?

The story is a dark corner of American history, but one that I think has resonance today. It’s coming out next May. My editor at Knopf, Ann Close, is a longtime Squaw faculty member. Likewise, my literary agent for all three of my books has been Michael Carlisle.

So, I guess I’m up here today because my story of connecting with other people at Squaw is an unusually fortunate one. I was lucky to find Michael, and my editor Ann, who was also Jim Houston and Oakley Hall’s editor: I feel proud to be part of that continuum.

Connecting with other writers and joining the continuum is a big benefit of being part of the Community of Writers.

But I don’t think nabbing an agent or an editor should be your main goal this week. I’d urge you, instead, to focus on the work and on building friendships with other writers. Our community is a special one because we emphasize the work – and on collaboration to make it better – rather than on the business side of publishing.

On a day-to-day basis, it was my greatest stroke of good fortune to have made friends with some of the people in that first workshop, who then went on to support me as I made the transition from journalist to author…

They’re the ones – the eight women in my workshop North 24th – who’ve seen me at my worst and my best over the years. They’re the ones, in the words of Annie Lamott, who’ve read all of my shitty first drafts…

…our workshop has been together for more than twenty years. I’m a relative newcomer to it having joined fifteen years ago. I count my blessings every day to have been invited to join them by my fellow workshopper Frances all those years ago. In fact, they workshopped this talk before I dared make it.

So, for those of you who are new to Squaw, here are my last words of

advice:

Read closely.

Try to read each piece twice, if you can – the first time without marking it up.

Be generous.

Get enough sleep.

Make friends with your favorite readers after workshop week ends….

And…remember… that one drink will hit you like two or three at high altitude!

The post Building a Vibrant Literary Community appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

May 7, 2017

Remembering 1882

On Saturday, May 6th, several hundred protestors gathered in San Francisco’s historic Portsmouth Square in Chinatown carrying such signs as “Remember 1882” and “2017 Has Become 1882.”

They were there to mark the 135th anniversary of the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first law implemented to exclude a specific ethnic group from immigrating to the U.S. It was one of the most shamefully racist pieces of legislation ever enacted in America and was repealed in 1943.

They were there to mark the 135th anniversary of the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first law implemented to exclude a specific ethnic group from immigrating to the U.S. It was one of the most shamefully racist pieces of legislation ever enacted in America and was repealed in 1943.

The crowd and speakers at the event drew parallels between the 1882 legislation, which was passed in an ugly outburst of nativism and was signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur, and the current administration’s proposed travel bans, barring of refugees, and immigration raids.

“We’re here to remember!” the Rev. Norman Fong, a Presbyterian minister who is executive director of the Chinatown Community Development Center. “What’s happening now in D.C. is like what happened to us before.”

The Rev. Fong’s remarks were proceeded by a pair of playful lion dancers, who wove in and out of the crowd before making their way up to the podium. There were also folk singers, and protestors in wheelchairs carrying signs reflecting the internment of Japanese Americans in the 1940s.

Portsmouth Square, the site where the American flag was first raised in San Francisco in 1846, is normally filled with men huddled around cards laid out on cardboard boxes and Chinese music. I’ve walked through it often over the past few years as I’ve researched my new book.

Just up the hill, in a spectacular building designed by the architect Julia Morgan, is the Chinese Historical Society of America‘s powerful exhibit, “Chinese American Exclusion/Inclusion.”

It is well worth visiting both places – Portsmouth Square and the Historical Society – if only to remember philosopher George Santayana’s warning that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Signs at the May 6, 2017 Rally for Inclusion in San Francisco’s Chinatown: the Tule Lake jersey the sign carrier is wearing is a reference to the Japanese internment camp.

The Rev. Norman Fong speaking at Rally for Inclusion

The post Remembering 1882 appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

April 5, 2017

Guidebooks to Sin

At opening night of the 2017 Tennessee Williams Festival in New Orleans, I met a librarian who also happens to be a champion ham kicker.

[image error]

Pamela D. Arceneaux at the Williams Research Center in New Orleans

She shimmied her way onto the stage of Le Petit Theatre du Vieux Carre in New Orleans in a sparkly black top and full-length skirt. Channeling the spirit of one of her heroes, Mae West, she delivered a lively and ribald talk on a subject that has fascinated her for some 35 years: the “blue books” of Storyville, the red-light district of New Orleans that flourished from 1897-1917. The “blue books” were guidebooks to the prostitutes and brothels in the district

The ham-kicking librarian wears spectacles and is nearing retirement. Her name is Pamela D. Arceneaux. She is the senior librarian and curator for rare books of The Historic New Orleans Collection, a non-profit dedicated to preserving the culture and history of New Orleans and the Gulf South. “Lookin’ at me, I don’t look like someone who talks about whores,” she deadpanned when we met a few days after the event, at her workplace, the hushed, wood-paneled Williams Research Center in the French Quarter.

The blue books that she loves carried advertisements for such brands as Budweiser, Veuve Clicquot, and Mumm, as well as patent cures for venereal diseases. The books barely mentioned sex itself, with the exception of passing references to “French” or “69.” Prices were not listed, either. Essentially, these pamphlets were Storyville’s marketing tools.

Arceneaux’s interest led her to write her newly published book, Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans. And she’s helping to produce a new exhibit opening at the Center on April 5th titled Storyville: Madams and Music, which will look at the rise and fall of the district, as well as the jazz that grew up alongside it.

Arceneaux’s interest led her to write her newly published book, Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans. And she’s helping to produce a new exhibit opening at the Center on April 5th titled Storyville: Madams and Music, which will look at the rise and fall of the district, as well as the jazz that grew up alongside it.

I’d seen the famous 1885 map of San Francisco’s Chinatown produced for the city’s Board of Supervisors detailing which buildings were brothels, gambling dens, opium dens, and so-called “joss houses,” or temples, in the course of researching my new book, Daughters of Joy. I’d also found tourist guides to Chinatown and to the adjacent Barbary Coast, San Francisco’s own Storyville. Talking with Arceneaux has inspired me to look again for West Coast versions of such “blue books.”

The highlight of the evening for me, and surely for Arceneaux, was the “ham kick” (watch the video here) – a re-creation by her colleague, Nina Bozak, of a light-hearted athletic contest staged in some Storyville saloons at the turn of the 20th century. The women would take off their underclothes and compete with each other to kick a ham strung up on a rope slung over a beam, which the proprietor could raise or lower at will. The winner – the woman who showed the most and/or managed to kick the ham the highest – got to keep this valuable foodstuff.

[image error]All in fun, the authors and actors involved in the opening night event staged a “ham kick” of their own (they used a real, seven-pound bone-in smoked ham, though they did keep their knickers on.) Arceneaux hadn’t intended to compete until she was prodded back onto the stage by Bozak, who is a library cataloguer as well as a dancer and choreographer. It was Bozak who’d found a mention of the “ham kick” in Al Rose’s 1974 book, titled Storyville, New Orleans. (A more recent history of the district, Spectacular Wickedness: Sex, Race, and Memory in Storyville, New Orleans, by Emily Epstein Landau, published in 2013, doesn’t mention this frivolity.)

And guess who won that evening’s contest?

“I won the ham kick by audience acclaim!” Arceneaux told me. She took her prize home that night (the ham came packaged in a red, mesh bag along with onions and other crawfish boil additions) and later donated it to J. & J. Sport’s Lounge because she and her husband are trying to cut salt from their diets. When I sat down with her several days later, Arceneaux was still glowing over her triumph in this bawdy contest from New Orleans’ past.

The post Guidebooks to Sin appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

February 9, 2017

Book Passage in Sausalito: Hope, Community, and Yes, Books

In these strange and often scary times, I’m sure I’m not the only one finding hopeful signs in whatever I can: a new baby, a sunny day, the fact that books by Rep. John Lewis, George Orwell, Sinclair Lewis, and, most recently, the long-departed Frederick Douglass are flying off the shelves.

And speaking of books, the literary website Lithub.com (highly recommended!), taking note of “the growing number of regularly scheduled book events across the U.S.,” just introduced a bimonthly column about community-based reading series. “Pages may be written in solitude, but the mingling and exchange of ideas at literary gatherings can be revitalizing for writers and lit enthusiasts, especially for those living in isolated areas outside cultural hubs.”

Here in the Bay Area, of course, we are far from isolated, part of a vast cultural hub. A major hub within that hub is my local bookstore, Book Passage, which for decades has been offering readings, classes, book groups, weekend conferences for mystery, travel, children’s picture book and YA authors, and other literary gatherings. The main store, in Corte Madera (Marin County), has barely enough space for all these activities, which, on top of everything else, include a Path to Publishing program for new or would-be authors. I should note that I am a part of that program, have taught classes in the store, and lead a long-running monthly book group there called Meet the Author.

One student, explaining that she would be a bit late each time because she’d be coming straight from another class, told me, “This store is my social life.” Book Passage is where people instinctively gather after local or national traumas, from 9/11 to political events last November. We all know the store’s owners, Elaine and Bill Petrocelli, because we see them in the store all the time. Sometimes they introduce and even interview the authors who flock here for readings almost every night of the week, on many afternoons and most weekends. (Elaine will interview Min Jin Lee, author of the well-received novel Pachinko, in Corte Madera on February 16.) Thirteen years ago, they opened a second, much smaller Book Passage in San Francisco’s Ferry Building.

And now—here comes the hopeful and joyous part—the Petrocellis have just opened a third store, in Sausalito, not far from the Sausalito ferry and the tourist haunts on Bridgeway. It’s another cozy book nook, whose windows offer wonderful views of the harbor. The grand opening party was last week, on a rainy Saturday afternoon, and you could barely get into the store. The place was crammed with both friends of Book Passage and denizens of Sausalito, who seemed utterly delighted—after cutting the official ribbon, Sausalito Mayor Ray Withy even said something like “You’re not a real community if you don’t have a bookstore.”

Book Passage by the Bay, 100 Bay St., Sausalito, 415.339.1300, bookpassage.com.

Photograph courtesy of the San Francisco Chronicle

The post Book Passage in Sausalito: Hope, Community, and Yes, Books appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.

October 19, 2016

The end of the library (as we know it?)

Ralph Lewin at the Mechanics’ Institute, photo courtesy of the Sacramento Bee.

A few months ago, San Francisco’s venerable Mechanics’ Institute hosted a discussion titled “The End of the Library (As We Know It)?”

As the oldest library in the city of San Francisco, the Mechanics’ Institute founded in 1854 and opened a year later with a grand total of four books, a chess room, and a mission to offer vocational education to out-of-work gold miners. (The San Francisco Public Library was founded more than two decades later, in 1879.) As one of the oldest libraries in the state, the Mechanics’ was a fitting place for this discussion.

I care deeply about what happens to our local libraries. I’m the proud holder of library cards in San Francisco, Marin, Napa, and Palo Alto. I recently renewed my membership in the independent Mechanics Institute, where I’ve been invited to speak about my books over the years. I regularly visit U.C. Berkeley’s libraries for research and also volunteer as a member of its Council of Friends of the Bancroft Library.

Libraries play a crucial role in supporting our democracy, encouraging the free flow of information, and as a much-needed non-commercial oasis. As Ralph Lewin, the Mechanics’ Institute’s executive director, told me recently, the fastest growing segment of his organization’s new membership is under 40 years old. Some tell him that they joined the Mechanics’ because it feels like an authentic institution that represents the soul of San Francisco. I’d agree with that.

In a city where there seems to be an ever deepening divide between the haves and the have-nots, libraries remain one of the few places where people of different ages, experiences, and backgrounds come together to discuss ideas. That, in itself, is a powerful argument for supporting our libraries at a time when public discourse has become increasingly fraught.

The discussion on libraries is an example of that and you can watch it on YouTube. But because I’m a bit of a library geek, I also took notes, which I’m sharing with you here. It was an all-star gathering of some of the country’s leading thinkers on libraries and is well worth watching. But if you don’t have the time, here’s my summary as well as some links to library resources.

Moderated by Ralph Lewin (RL), the panel included Susan Hildreth (SH), executive director of the Peninsula Library System and previously President Obama’s Director of the Institute for Museum and Library Services, Luis Herrera (LH), San Francisco’s City Librarian and a board member of the Digital Public Library of America, Deborah Hunt (DH), Library director of the Mechanics’ Institute, and Greg Lucas (GL), State Librarian of California.

Here are some of the highlights from my edited notes on the discussion, with the speakers identified by their initials.

Spiral staircase at the Mechanics’ Institute

RL: “Is the library a relic? And what’s happening at the San Francisco Public Library these days?

LH: The idea that libraries are a relic is highly exaggerated. We’re thriving. We’re renovating eight new buildings. We’ve got close to 7 million visitors each year. Our circulation is about 10.6 million items borrowed, about half of that e-media, which saw a 50% increase last year.

GL – As state librarian, my job is spreading the good word and listening to people. People love libraries so much they don’t think they are part of government. We see immigrant families coming into libraries – know nothing bad will happen to them there and someone there will help them with their issues. You see filled rows of computer terminals – a high percentage of people still don’t have Internet access at home. Remember – it was a big idea at the time when the Internet first took off that people wouldn’t need libraries anymore. Instead, we’ve seen libraries quickly adapt.

SH – The Gates Foundation decided to sunset their investment in libraries. Gates helped fun Aspen Institute’s report on library: “Rising to the Challenge: Re-envisioning Libraries.” One of the key ideas from report is that libraries remain an important platform for community and individual development.

DH – I’m often asked “why do we need librarians when have Google search?” She holds up a copy of the “Badass Librarians of Timbuktu,” a new nonfiction book by Joshua Hammer on the librarians’ race to save precious manuscripts from destruction. “Sadly, the “l” word has become very stereotyped…. I don’t tell people that I’m a librarian (mimes yawning) and instead I tell people that I am a strategic information professional!”

LH: Libraries are among the most democratic institutions. We welcome everyone. We serve everyone from a research scholar to a new immigrant. When the idea of us working with public health department came us, we said, why not? Libraries are also a focal point for civic dialogue. SFPL has half a million people attending its functions. We play an important role in encouraging civic engagement and and as a community hub.

RL: (Question to Greg Lucas, a former journalist.) “You covered politics for a long time. How do libraries fit in?”

GL: They’re part of local government, usually in the general fund expense. The general fund is fairly small and fairly prescribed. In places where libraries aren’t valued, there’s some debate over whether to fund public safety vs. libraries. (But I’d argue) the library is the happiest face a city or county can put on itself. Libraries have to get out and demonstrate their value to the community. Some libraries have contracts with the county to do literacy classes in county jail. It’s a whole lot tougher then for sheriff to throw library under the bus (in terms of funding) when working together, adding a film reference, “It’s Chinatown, Jake.”

DH: I think libraries are the most democratic institutions we have.

GL: We talk about how libraries are engines of economic development – we often have someone coming in and asking a librarian to review a resume.

Q: Last week, while looking through microfilm at the SFPL’s main branch, I overheard a librarian handling a difficult client – perhaps a homeless person. How do you support your librarians in addition to the social worker you have on staff at the main branch?

LH: Incidents have dropped dramatically over the past year and a half, in part because partnering with the San Francisco Police Department and social service agencies. Also, we’ve set some limits and expectations about behavior – after that, there are consequences.

The post The end of the library (as we know it?) appeared first on Julia Flynn Siler.