Julia Flynn Siler's Blog, page 11

September 26, 2011

Tipping the Coconut in South Kona

Sipping kava at Ma's in South Kona

I caught a glimpse of the sign out of the corner of my eye: "Ma's Nic Nats & Kava Stop." I made a quick U-turn on the Mamalahao Highway in South Kona and headed back, pulling across from a laundromat where children chased each other outside as their parents waited for clothes to dry.

From the outside, the kava bar didn't look like much. But it was starting to rain and I had another hour before I could check into my hotel room. So I climbed out of my car and walked in.

It was a tiny place, with perhaps 10 seats. Tending bar was Ma, the kava stop's namesake. A Hawaiian woman with a broad smile, she welcomed me in. The bar itself was made of carved mango wood, salvaged from trees cut down to make way for a new coffee plantation.

A young woman from Northern California sat on a bar stool. Her two friends, refugees from Colorado who'd moved to the islands five years ago, sat at a small table. They all held coconut shells with long straws sticking out. Sipping kava mixed

with pineapple and coconut juice, they all had relaxed smiles on their faces.

"Try this" Ma told them, as she handed them a long slice of dried fish. "It real ono."

She made me the same $5.00 kava drink. It tasted good, though I later realized she'd given me a beginner's draw, nice and sweet. Within a couple of minutes, my mouth began to tingle and I started to feel light-headed. I drank more. (Kava, like coffee, is not regulated.)

I'd seen an awa plant, which the drink is made from, that morning at the Bishop Museum's Amy B. H. Greenwell Ethnobotanical Garden in South Kona,. A member of the black pepper family, roots of the kava (which is the name for it in Tonga and the Marquesas – Hawaiians call it 'awa) were traditionally chewed. Then the chewed mass was put into a bowl, mixed with water, and strained.

When the first European visitors came to the Hawaiian islands in the late eighteenth century, Polynesians would offer their drink made from the kava root to these honored guests. It also played a part in religious ceremonies as an offering to the gods.

Nowadays, machines macerate the dry roots into a fine powder which is then mixed with water. The drink's allure comes from kavalactone, a compound which acts as a relaxant or sedative, with a mild numbing effect. It doesn't seem to effect mental clarity.

When I told a new friend about my experiment with kava later that night, he laughed and described it as being "sort of like a mud Novocain drink." He and his wife had tried it in Samoa, where — to hear him tell it — the roots are ground up along with a lot of dirt, making drinking it an experience not unlike sipping from a mud puddle.

Oddly, kava bars are starting to pop up on the mainland, including one called the "Kahuna 'Awa Kava Bar" in Deerfield Beach Florida. The Yelp reviews of this place are probably more fun to read than the experience of drinking kava itself.

Oddly, kava bars are starting to pop up on the mainland, including one called the "Kahuna 'Awa Kava Bar" in Deerfield Beach Florida. The Yelp reviews of this place are probably more fun to read than the experience of drinking kava itself.

Rony, from Miami, was shocked by the price: "$25 a bowl! Is this stuff harvested by Swiss financial planners?" Another described it as tasting like "pistachio nut shells covered in dirt."

Mine actually tasted pretty good. Maybe Ma just has a better recipe. She offered my kava up with sweet aloha, giving me a warm hug goodbye. But I don't think I'll empty another coconut shell of the stuff anytime soon. I'd love to visit Ma again, but next time will just order a smoothie — hold the kava.

September 13, 2011

Improv for Writers

I was at the bottom of a long wait list with faint hope of getting in. But just days before the start of a four-day improvisation workshop last month I got a call from BATS (Bay Area Theatre Sports) asking whether I'd like to join its intensive class led by the legendary teacher Keith Johnstone.

I'm not sure why I lucked into such a last-minute opportunity, but I dropped everything and did some swift scheduling improv of my own. I pushed an interview for a newspaper story I was researching into the following week and found other parents to drive my teenagers around. As it turned out, my last-minute scramble was worth it.

I needed to regain my spark. My mother had died two months earlier and my normally deep reserves of playfulness and creativity had vanished over the summer. I wasn't laughing much and couldn't seem to see beyond my own sadness. I mourned the loss of my mom, who had been both my biggest critic and my most outspoken fan.

I also felt daunted by the prospect of getting up in front of a bunch of strangers and play-acting on stage, especially while grieving. I would have forgiven myself if I'd chosen to skip the workshop. But I'm glad I didn't because it helped pull me out of my fog of sadness. For the first time in months, I found myself laughing so hard that tears rolled down my cheeks.

Keith Johnstone, who is British, began his career in the scriptwriting department of London's Royal Court Theatre in the late 1950s. In the half century since then, he has been teaching people to unlock their creativity. He's worked with famous actors as well as writers. His techniques are about the psychology of performance – letting go of a fear of failure and relaxing enough to make sure you and everyone around you are having fun.

Keith is the author of books that improvisational companies all over the world have turned to for inspiration: Impro, first published in 1979, and Impro for Storytellers. But getting up on stage in front of a famous teacher wasn't the only reason why I felt dread. Making up stuff during some of his exercises intimidated me – after all, my writing as a journalist and a writer of history is all about not making stuff up.

Keith's disarming charm and willingness to make himself vulnerable (he was taking some new medications which were making him dizzy, which he referred to frequently) transformed my reluctance into enthusiasm. By day three, my hand kept shooting up – almost against my will — to volunteer for exercises designed to foster spontaneity.

Yes, that was normally prudish me – mother of two, happily married to the same man for many years — taking part in the early stages of a rather curious threesome with another woman and a man. I was also a wantonly abandoned mistress luxuriating in an imaginary bubble-bath and urging her manservant to scrub her harder. Other sketches were pretty ordinary, but it was fun to play a naughty vixen on stage, as well as the matriarch of a large Israeli family, a teenage daughter facing the wrath of her parents for coming home late, and a robot controlled by a human.

Some of my favorite moments over the four days involved the exercises involving status transactions, which are a crucial topic for improvisers. We'd play high status characters who looked people directly in the eyes, threw their shoulders back, kept their toes pointed outward, and held their heads steady as they spoke – and then switch to low-status characters who averted their eyes, stuck their teeth over the lower lips, turned their toes inward, and talked breathlessly.

Master-servant skits endlessly entertained us, especially when we switched roles back and forth in what Keith calls the "see-saw" principle, which is at the root of most great comedy and tragedy (think King Lear, who begins as a high status character and descends about as low as possible into madness following the storm on the heath.) After class, I'd find myself noticing status interactions in real life: at the check-out counter on the grocery line or back-to-school night.

We had a few talented ringers in our class, who revealed themselves in an evening performance directed by Keith half-way through the workshop. These are people who are deeply devoted to improv and have regular troupes of their own inJapanand elsewhere. It was a pleasure to work and learn from them, as were the shorter classes held at the end of each of the four days led by the gifted coaches William Hall and Rebecca Stockley.

Facing the prospect of doing more public speaking in a few months, when my next book Lost Kingdom, is published, Keith's workshop reinforced the idea that mistakes are okay. It might be even be more fun to occasionally toss out the script and just see what happens once in a while.

April 28, 2011

An Afternoon with a U.S. Poet Laureate

As a long-time reporter, I've met a lot of people. Perhaps the most inspiring was our recent U.S. Poet Laureate, William S. Merwin.

For decades, Merwin has lived off the grid in Hawai'i. To reach his home, I turned off Maui's fabled Hana Highway, down a single lane edged with red volcanic soil. About a quarter of a mile from steep cliffs dropping to the sea, the foliage began to grow thick. Rustic wire fencing strained to hold back arching fronds and tropical blooms. His 19-acre palm forest seemed like it was trying to swallow the lane.

W.S. Merwin's palm forest (photo: Tom Sewell)

There was no hint that this was the home of a celebrated writer – just a swinging metal gate secured with chain – the same kind used by neighbors raising cows and chickens. A sign on a nearby property reads "Respect the keiki," the Hawaiian word for children.

Just beyond the gate was a modest carport. Mounted on its roof were solar panels which supply all of the home's power. Several hundred yards beyond the carport, down an unpaved track, was the Merwin's self-sufficient home, which seemed to disappear into the jungle.

Paula, William's wife, met us on the outside lanai, where we slipped our shoes off and entered. My first impression of the house was that it was like a Polynesian longboat – a rectangular floor plan, with wood on the ceilings and darkly oiled eucalyptus wood floors.

Books were everywhere — books on gardening right at the entrance, cookbooks in the bathroom, an entire extra room downstairs devoted to books, whose shelves overflowed, leaving volumes stacked on the floor.

We sat in what the Merwins call their breakfast lanai – a covered porch that leads from the kitchen looking directly out onto the palm forest. That's where the couple has their breakfast and where they spend time with visitors. Unlike the darker living room, it is light-filled and hospitable, even during torrential downpours.

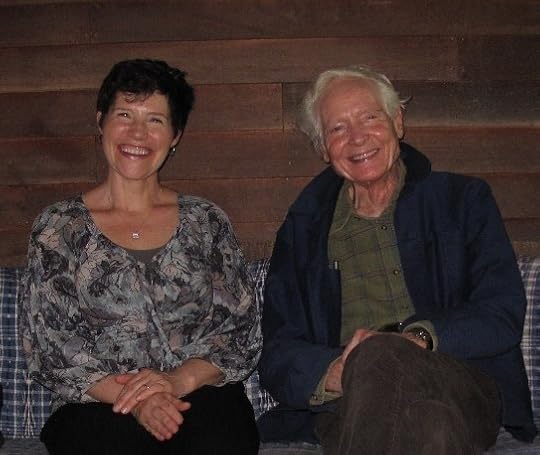

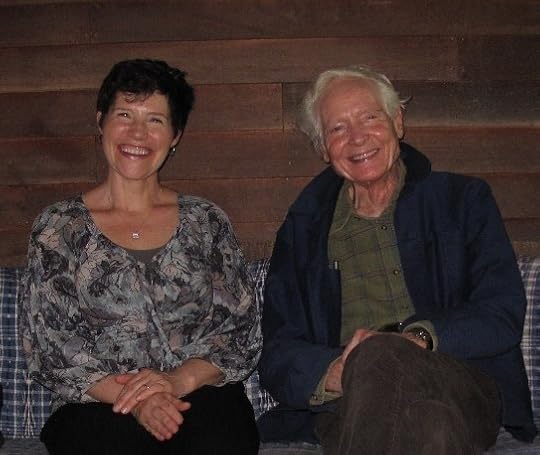

Julia and W.S. Merwin (photo: Tom Sewell)

They'd lit incense to keep the mosquitos away and William and I sat on the lanai at the beginning of our visit. Our talk meandered. I could sense he was sizing me up and trying to decide whether he'd cut the visit short or spend just the allocated time with me. He ended up spending more than four hours with me – a gift I'll never forget.

What struck me most was his incredible mind. As we rambled through his forest, he was able to pull up the Latin names of obscure palms, remembering where he got them, as well as often funny stories about the genus or how he got the plants as well. He's 83, but possesses a sharper intellect than perhaps anyone I've ever met.

He was also very kind. I'd wrecked my knee in a ski accident and recently had reconstructive surgery to fix it. William was very thoughtful about my knee, providing me with a bamboo walking stick for our hike around the property where he's planted hundreds and hundreds of palms.

We'd walked for about half an hour when he paused at the greenhouse where he grows palms from seed. He stopped to quote a 14th century Japanese Zen master whose poetry he'd helped translate on the different reasons why people create gardens. He also quoted Robert Frost grumpily commenting, after a radio interview, that journalists somehow assumed that writers cared about being in the press, confessing his exhaustion with being in the public eye as poet laureate.

He also spoke of how he'd become involved in Hawaiian activism (protesting the bombing of the island of Kaho'olawe ) but added that some of the activists had gotten violent and didn't want haoles (foreigners or people who are not native Hawaiians) involved, so he and Paula had dropped out. He had also studied the Hawaiian language and had an appreciation of chant and oli (a chant that was not danced to).

We discovered we were both admirers of Hawaiian language scholar Puakea Nogelmeier, and that William had been introduced by Puakea to his mentor Theodore Kelsey in the hospital, shortly before Kelsey's death. He also told me stories of how botanists and other plant enthusiasts had sent him palm seeds from around the world.

William struck me as someone who had truly given something meaningful to his adopted home of Hawai'i – rather than being like the migrating kōlea, a bird from the mainland that gorged on the most luscious berries and choicest fruits from the islands, then took off again for the mainland. The kōlea, like so many other visitors, took from Hawai'i without giving back.

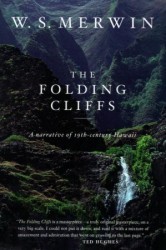

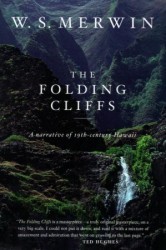

Merwin's The Folding Cliffs

But William and Paula had turned agricultural wasteland into a beautiful forest. He'd also contributed to a deeper understanding of Hawai'i an history through his book, The Folding Cliffs, which in poetic language grappled with the same tragic history that I've been immersed in for the past few years.

I'm deeply grateful to my editors at the Wall Street Journal for giving me a reason to meet William and Paula. In honor of National Poetry Month, here's a line from one of William's best-known poems titled "Place."

"On the last day of the world / I would want to plant a tree."

To learn more about William and the palm forest that he and Paula have created, visit the Merwin Conservancy's website.

An Afternoon with the U.S. Poet Laureate

As a long-time reporter, I've met a lot of people. Perhaps the most inspiring was our current U.S. Poet Laureate, William S. Merwin.

For decades, Merwin has lived off the grid in Hawai'i. To reach his home, I turned off Maui's fabled Hana Highway, down a single lane edged with red volcanic soil. About a quarter of a mile from steep cliffs dropping to the sea, the foliage began to grow thick. Rustic wire fencing strained to hold back arching fronds and tropical blooms. His 19-acre palm forest seemed like it was trying to swallow the lane.

W.S. Merwin's palm forest (photo: Tom Sewell)

There was no hint that this was the home of a celebrated writer – just a swinging metal gate secured with chain – the same kind used by neighbors raising cows and chickens. A sign on a nearby property reads "Respect the keiki," the Hawaiian word for children.

Just beyond the gate was a modest carport. Mounted on its roof were solar panels which supply all of the home's power. Several hundred yards beyond the carport, down an unpaved track, was the Merwin's self-sufficient home, which seemed to disappear into the jungle.

Paula, William's wife, met us on the outside lanai, where we slipped our shoes off and entered. My first impression of the house was that it was like a Polynesian longboat – a rectangular floor plan, with wood on the ceilings and darkly oiled eucalyptus wood floors.

Books were everywhere — books on gardening right at the entrance, cookbooks in the bathroom, an entire extra room downstairs devoted to books, whose shelves overflowed, leaving volumes stacked on the floor.

We sat in what the Merwins call their breakfast lanai – a covered porch that leads from the kitchen looking directly out onto the palm forest. That's where the couple has their breakfast and where they spend time with visitors. Unlike the darker living room, it is light-filled and hospitable, even during torrential downpours.

Julia and W.S. Merwin (photo: Tom Sewell)

They'd lit incense to keep the mosquitos away and William and I sat on the lanai at the beginning of our visit. Our talk meandered. I could sense he was sizing me up and trying to decide whether he'd cut the visit short or spend just the allocated time with me. He ended up spending more than four hours with me – a gift I'll never forget.

What struck me most was his incredible mind. As we rambled through his forest, he was able to pull up the Latin names of obscure palms, remembering where he got them, as well as often funny stories about the genus or how he got the plants as well. He's 83, but possesses a sharper intellect than perhaps anyone I've ever met.

He was also very kind. I'd wrecked my knee in a ski accident and recently had reconstructive surgery to fix it. William was very thoughtful about my knee, providing me with a bamboo walking stick for our hike around the property where he's planted hundreds and hundreds of palms.

We'd walked for about half an hour when he paused at the greenhouse where he grows palms from seed. He stopped to quote a 14th century Japanese Zen master whose poetry he'd helped translate on the different reasons why people create gardens. He also quoted Robert Frost grumpily commenting, after a radio interview, that journalists somehow assumed that writers cared about being in the press, confessing his exhaustion with being in the public eye as poet laureate.

He also spoke of how he'd become involved in Hawaiian activism (protesting the bombing of the island of Kaho'olawe ) but added that some of the activists had gotten violent and didn't want haoles (foreigners or people who are not native Hawaiians) involved, so he and Paula had dropped out. He had also studied the Hawaiian language and had an appreciation of chant and oli (a chant that was not danced to).

We discovered we were both admirers of Hawaiian language scholar Puakea Nogelmeier, and that William had been introduced by Puakea to his mentor Theodore Kelsey in the hospital, shortly before Kelsey's death. He also told me stories of how botanists and other plant enthusiasts had sent him palm seeds from around the world.

William struck me as someone who had truly given something meaningful to his adopted home of Hawai'i – rather than being like the migrating kōlea, a bird from the mainland that gorged on the most luscious berries and choicest fruits from the islands, then took off again for the mainland. The kōlea, like so many other visitors, took from Hawai'i without giving back.

Merwin's The Folding Cliffs

But William and Paula had turned agricultural wasteland into a beautiful forest. He'd also contributed to a deeper understanding of Hawai'i an history through his book, The Folding Cliffs, which in poetic language grappled with the same tragic history that I've been immersed in for the past few years.

I'm deeply grateful to my editors at the Wall Street Journal for giving me a reason to meet William and Paula. In honor of National Poetry Month, here's a line from one of William's best-known poems titled "Place."

"On the last day of the world / I would want to plant a tree."

To learn more about William and the palm forest that he and Paula have created, visit the Merwin Conservancy's website.

September 15, 2010

Revisiting the Mondavis

A few years back, a friend asked me to donate a unique item to a fund-raiser for a local non-profit, the Marin Art & Garden Center. I would lead the winning auction bidders on a bike tour of Napa Valley, showing them favorite spots I'd discovered in my research for The House of Mondavi, my first book which began as a front page story for the Wall Street Journal.

Last weekend, as the grapes still hung on Napa's vines during this unusually cool growing season, I met up with the winning bidders for our day of pedaling and wine-tasting together. For me, it was an opportunity to check in with friends in the Valley about what had changed since The House of Mondavi came out three years ago. My book had detailed the rise and fall of the pioneering Mondavi family's wine business, a story full of visionary brilliance as well as painful family discord.

Peter Mondavi Sr., I learned, still goes to work every day at the original family business, the Charles Krug Winery. Last weekend, it drew seven hundred visitors for its annual Tastings on the Lawn gathering, which first began in 1951 with wine tasting and music on the Carriage House Lawn. Although he sadly lost his wife Blanche earlier this year, he's still enjoying life — including a glass of his winery's Family Reserve Generations each evening at about six.

Robert Mondavi, who helped build Napa's reputation as a world-class wine region, had passed away in 2008, but according to our guide at the Charles Krug winery, his remains didn't end up joining those of his parents and sisters at the Mondavi family crypt at St. Helena's Holy Cross Cemetery. Instead, our guide said he had discovered a plain stone marker for Robert at the non-denominational St. Helena Cemetery. Did that mean the rift between Robert, his second wife, Margrit, and the Peter Mondavi side of the family had never fully healed? I hope not.

Margrit Mondavi, the only family member still affiliated with Robert Mondavi Winery.

Robert's eldest son, Michael, is now owner of Folio Fine Wine Partners, producing wine and marketing other small brands. Michael's brother Timothy and sister Marcia are partners in another venture, the Continuum Estate. Margrit Mondavi, Robert's widow, is the only member of the family still working for the Robert Mondavi Winery, as vice president for cultural affairs.

While Mrs. Mondavi can still call the winery home, the house she and Robert built off the Silverado Trail, which they called Wappo Hill, is for sale. Michael Mondavi and his siblings are trustees of the estate, which is on the market for $25 million.

Wappo Hill's 11,500-square-foot home was built in 1984 in a design by Cliff May, who is probably best known for designing Sunset magazine's Menlo Park, Calif., headquarters. The house has an open floor plan, with just two bedrooms and an indoor swimming pool adjoining the living area – perhaps a testament to Robert Mondavi's preference for open spaces. In a 1989 piece about the house in Architectural Digest, he told the reporter, "I hate the feeling of being confined."

The view from Wappo Hill

You can take a peek at photos of Wappo Hill here. Whoever buys the house will be neighbors with Robert's sons, who built their own homes nearby. Let's hope whoever buys it will honor the spirit of the home's original owners and raise many a glass there among friends (as well as by plunging into the 50′ pool during exuberant parties!).

September 7, 2010

Singing with the choir

Early on in my search to understand the last queen of Hawai'i, I met with Corinne Chun Fujimoto, curator of Washington Place, the gracious, white-columned home in downtown Honolulu where Queen Lili'uokalanis had spent the last years of her life.

Corinne suggested that the best place to look for the queen was not through the places she lived, nor even through the words she wrote in official documents, diaries or correspondence, but in Lili'uokalani's music. So I began with The Queen's Songbook, a monumental, decades-long effort to collect and publish the queen's compositions. The task began in 1969 and took more than twenty-five years to come to fruition.

The Songbook was based on a collection that the queen herself had hoped to publish in the late 1890s but never did: "He Buke Mele Hawaii: Hawaiian Songs with Words and Music." For a century or so, the manuscript had been tucked away in the state archives.

One of the many, many people who contributed to The Queen's Songbook was Nola A. Nāhulu, who now directs the choir at Kawaiaha'o Church. "Auntie Nola," as some of the younger choristers call her, holds a storied position: Lili'uokalani herself directed the same choir a century earlier and loved playing the church's great pipe organ.

Nola A. Nāhulu, director of the Kawaiaha'o Church choir and the Hawaii Youth Opera Chorus, leads choristers in an outdoor performance at 'Iolani Palace.

So it was with delight and some trepidation that I accepted an invitation to sing with the choir at a Sunday service, directed by "Auntie Nola." I sang with the soprano choristers, who wore formal mu'mu'u dresses in a pattern of green, black and white brightened with sprays of delicate orchid blossoms. Green silk lei hung around their necks.

We sat together in the first floor choir stall, at the back of the church looking over the congregation. Singing directly in front of me was Malia Ka'ai-Barrett, who works alongside Nola as general manager of the Hawai i Youth Opera Chorus. Although I can sight-read and I sing with my own church chorus at St. John's Episcopal Church in Ross, California, I was relieved to follow Malia through the hymns we sang in Hawaiian.

Behind us was the massive pipe organ, played by Richard "Buddy" Naluai. As one of the first Christian churches in the islands, made of thousand-pound blocks of coral stone cut and then dragged from the sea, the building is on the Registry of National Historic Places.

Kawaiaha'o was the church for Hawai'i's ali'i – its chiefs – and I sat almost at eye level with the powerful portraits of the kingdom's rulers that hung on the walls. The sermon by Kahu (Reverend) Curt Kekuna started off with the question: "Why are you here?" and went on to preach, "We're not here to create another Christian country club … we're here to go out and transform the world!"

Claire Hiwahiwa Steele, left, and me in front of 'Iolani Palace.

Why was I here? I'd been invited to join the choir Claire Hiwahiwa Steele, whom I'd met in a Hawaiian studies class at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa earlier in the week. Claire is not only a member of the choir but also the church's newest trustee. A graduate of Kamehameha Schools, she is a recipient of a church scholarship that's allowed her to pursue a master's degree at UHM.

I couldn't pass up the opportunity to sing the queen's songs in her own church with people who'd grown up with her music . And the experience profoundly moving — joining together with these beautiful voices to perform the queen's own songs. It touched me in a way that no amount of reading or writing ever could.

Yet , I was also there as an author and journalist: I couldn't resist pulling out my reporter's notebook during the service. Or, for that might, smiling with recognition when I spotted choristers tapping away on iPhones and Blackberries while I was scribbling in my pad. Good thing Auntie Nola didn't catch us!

September 3, 2010

Paying Respect

September 2nd is the day that the last ruling monarch of Hawai'i was born and I was invited by the trustees of the Queen Lili'uokalani Trust to join them at a ceremony honoring her birthday at Mauna ʻAla, the Royal Mausoleum where members of both the Kamehameha and Kalākaua dynasties are buried.

The last queen was the successor to her brother, David Kalākaua, and the last ruler of the islands. Born in a grass hut in 1838, Lili'uokalani was a fervent patriot who struggled for the restoration of her land and the rights of her people for most of her life. She died in 1917, nearly two decades after America had annexed her independent Kingdom of Hawai'i.

At the offices of the Lili'uokalani Trust, a poster depicting the late queen is draped with a lei tribute.

Yesterday morning, we headed up towards the mountains, along Nuʻuanu Avenue to pay our respects to her. It was sprinkling when we arrived, but the clouds soon parted and the air grew steamy. The white-clad members of the Royal Hawaiian Band, one of the oldest continually performing municipal bands in the U.S., began to play.

The birthday commemoration for Queen Lili'uokalani was held at Mauna 'Ala, the Royal Mausoleum, in the hills above downtown Honolulu.

The Daughters and Sons of Hawaiian Warriors, along with descendants of the Hawaiian royal family, were there. So were some of the Hawaiian children who were beneficiaries of the trust that Lili'uokalani set up in 1909. (For more information on the history of the trust, take a look at a fascinating article in the Hawaii Bar Journal from May of 2009 entitled "The Queen's Estate" by Samuel P. King, Walter M. Heen, and Randall W. Roth.)

The Queen Lili'uokalani Children's Center, the operating unit of the trust, organized the program at Mauna ʻAla. According to Trustee Claire Assam, last year the trust spent $14.7 million to help care for 1,441 orphan children and 9,531 destitute children. All of its revenues come from its real estate holdings, which include 6,330 acres of land, mostly on Hawai'i Island (also called the Big Island).

High school students who chanted for the late queen. Beneficiaries of the Lili'uokalani Trust also attended the ceremony.

I brought a lei of crown flowers – the delicate, lavender-colored blooms that were the queen's favorite – to place in her crypt, after all the dignitaries had made their way down into the tomb and back with their offerings. I walked down the steps, took off my sandals, and entered the cool, dark space, which is normally gated off to the public. It was the closest I had gotten to her — at least physically — in the three years I've been working on The Lost Kingdom.

Then I said a prayer, reflecting on what I'd learned from the past few years of trying to understand her through her letters and diaries, and through the numerous historical documents and books written about 19th-century Hawai'i. The reverence she was accorded on this day was its own eloquent testament to her life and legacy.

Dignitaries descend into Lili'uokalani's crypt during the ceremony marking her birthday.

I wasn't the only one who found it moving. Honolulu's acting mayor, Kirk W. Caldwell, also attended the service. He remarked, "It's a reflection on what the ali'i [the Hawaiian royals] have given this community – the trusts, the Queen's Hospital, which is the best hospital in the state, the Kap'iolani Women and Children's Hospital where almost everyone was born…" "adding "it was a little bit chicken skin for me as I went down into the vault."

September 1, 2010

My Dinner with Amy

I knew I'd found a soul sister who also loved research when I clicked onto Amy Stillman's blog and found her posting, "Adventures in Archives."

For the past three years, I've been making trips to the treasure trove of Hawaiian historical archives located in Honolulu. Amy Ku'uleialoha Stillman, a Harvard-educated associate professor of music and American culture at the University of Michigan, likewise had just arrived on the islands and couldn't resist making a trek to the Hawaii State Archives, with a long list of things just to "spot check."

Amy Stillman (photo: Honolulu Magazine)

She signed into the archive, put her purse into a locker, and fired up her Mac. With the help of archivist Luella Kurkjian, who safeguards the most precious manuscripts locked away in the safe as chief of the archives' historical records branch. Amy found a lot more than she'd bargained for, opening up a "whole new can" of scholarly worms, she told me. Ah, happiness!

Luella Kurkjian of the state archives staff

Amy, who is a Hawaiian, will serve as the Dai Ho Chun Distinguished Visiting Professor at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa. A meticulous scholar and powerful writer, I first came across her work in an article she published in 1989 in The Hawaiian Journal of History.

Titled "History Reinterpreted in Song: The Case of the Hawaiian Counterrevolution," Amy wrote the article when she was still a doctoral candidate in musicology at Harvard, where she'd gone after studying at the University of Hawai'i. I read an article in the current issue of Honolulu Magazine that Amy had just returned to her home state for a year, so I decided to email her, asking if we could meet.

Not only did she say "yes," but she offered to pick me up, drive me to a marvelous Hawaiian-Vietnamese restaurant called Hale Vietnam, and then return me to the hole-in-the wall where I stay when I'm digging through the archives. All I can say is mahalo, Amy, for the chance to spend an evening with you and to share that heavenly lychee sherbert – real ono!

But what really hooked me were Amy's descriptions of her recent discoveries in the archives concerning Queen Liliʻuokalaniʻs 1897 manuscript "He Buke Mele Hawaii." The excitement and sheer staying power that drives her as a researcher is inspiring and it comes through in her series of postings about what she found. Take a look at her postings, especially her praise of the Hawai'i State Archives staff.

Ancient Hula Hawaiian Style, Volume 1: Hula Kuahu

Did I mention she's not just a scholar, stuck in dusty archives, but also the director of the Great Lakes Hula Academy in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and producer of a Grammy-winning album 'ikena, by singer Tia Carrere and singer/songwriter and co-producer Daniel Ho? Amy's latest project as a producer is an album of some of the greatest hits of ancient hula, called Ancient Hula Hawaiian Style, Volume 1: Hula Kuahu, through Michael Cord's Hana Ola Records.

'ikena

On the drive back to my place, I asked Amy what music she'd recommend for me. Aside from her post on "Top Ten Hawaiian Albums for Newbies," she also suggested a group from Michigan called The Rose Ensemble, based in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Nā Mele Hawai'i

, "You will never hear Aloha Oe quite the same way again after hearing Ke Aloha a ka Haku (The Queen's Prayer, track 27), written by Lili'uokalani from her prison cell in 1895, and the earlier and later works all have stories to tell as well. Very highly recommended to anyone with the slightest interest in Hawaii, regional American music, or issues of colonialism in general."

Amy, not surprisingly, helped produce that CD, too.

August 31, 2010

Searching for Kau Kau

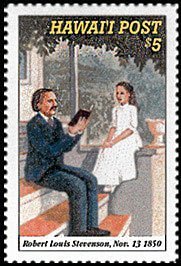

I first came across the word kaukau in a note that the Hawaiian Princess Ka'iulani wrote to Robert Louis Stevenson more than a century ago.

The Scottish novelist and his family had arrived in Honolulu in the afternoon of January 24, 1889, and the beautiful princess dropped them a short note, inviting them to her family's estate and adding that "Papa promises "good Scotch kaukau…."

To try to track down the word's meaning, I went to the Hawaiian Electronic Library Web site, which searches several Hawaiian dictionaries simultaneously. But because Hawaiian words can have multiple meanings depending on their diacritical marks (which weren't used in the 19th century) the modern Web site offered an array of possible spellings and definitions.

The relationship between R.L. Stevenson and Ka'iulani was depicted on a commemorative postage stamp in 2000.

Could it mean "to slow down, linger or procrastinate?" Hmm. Stevenson and Ka'iulani did famously sit together under the spreading banyan tree at 'Āinahau, her family's estate at Waikīkī. But probably not, given the context of the sentence.

Or did kaukau mean, in another definition, "a hemorrhoid or exterior obstruction to bowel evacuation"? Almost certainly not. A well-educated Victorian lady, no matter how earthy her humor might have been, would never had written such a thing to the eminent author of of Treasure Island, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Kidnapped!.

Or could it be Pidgin, the uniquely Hawaiian language that developed from the islands' mix of immigrant influences? Checking a Pidgin-specific dictionary at e-Hawaii.com, the definition was "food; meal; to eat." This clue led me to the right entry on the original dictionary site.

Bingo!

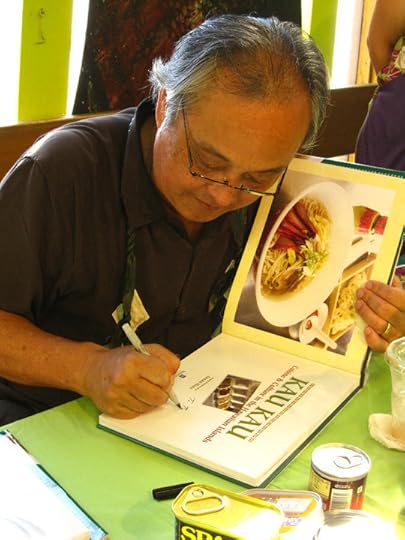

Arnold Hiura signs a copy of his book. (photo courtesy Arnold Hiura)

This week in Honolulu, I came across the word kaukau again, in a small notice for a talk on Sunday afternoon by Arnold Hiura at Native Books in the Ward Warehouse. In his first book, titled Kau Kau: Cuisine & Culture in the Hawaiian Islands, Hiura relates that growing up, "when someone bellowed, 'Kau kau time,'" it was the equivalent of saying "Chow time!" or "Come and get it!"

Originally he'd thought the word was from the native Hawaiian language. But over the three years he took to write his marvelous food history of the islands, he learned the original derivation of the word, stemming from "chow chow," which is Chinese for "food."

The mystery deepens, though. Chinese contract workers were first brought to the islands in 1852 to labor on sugar plantations. Would the princess, who was born in 1875 and died at age 23 in 1899, have known the slang that these workers used to describe their food?

The fact is that by 1889, when Ka'iulani wrote her note, Chinese cultural influence on the islands was ubiquitous enough to have influenced everyday language at all levels of society. By the 1884 census, according to Thrum's Hawaiian Annual, there were nearly 18,000 Chinese in Hawai'i, making them the largest immigrant group by far – dwarfing the American presence and rapidly catching up to the native Hawaiian population, which had dwindled to just over 40,000. Honolulu's Chinatown had long been a bustling waterfront commercial hub, and in 1889 the district was rapidly recovering from a fire three years earlier that destroyed 7,000 Chinese homes and caused $1.5 million in damage (more than $30 million today).

Hiura himself grew up on a sugar plantation on the Island of Hawai'i, working there periodically until his early twenties. He remembered how he and the other workers would stop work when the whistle blew mid-day and take out their metal lunch cans – the bottom half filled with rice and the top with vegetables or pickles. They'd all squat down to eat, reaching over and picking from their co-workers' cans for tastes of different toppings.

The night before his book talk, he and his wife Eloise had attended a "plantation potluck" in Hilo in which everyone brought their favorite dishes from the old days, when the islands still had sugar plantations (there is only one left now: the Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Co. on Maui). As they described the way in which sharing their food created feelings of closeness, another Pidgin term popped up: real ono – an allusion to the prized ono tuna fish, slang among young Hawaiians for something truly fabulous.

August 29, 2010

The Queen's Prayer

The last queen of Hawai'i's best known composition is Aloha Oe, which is heard in the soundtrack of everything from Elvis Presley's "Blue Hawaii" to the Disney movie "Lilo and Stitch." But the one that brought tears to my eyes this morning was "The Queen's Prayer," a hymn she wrote when she was imprisoned for eight months following a failed insurrection against the 1893 overthrow of the independent kingdom of Hawai'i.

A tribute to Queen Lili'uokalani at the Kawaiaha'o Church

Every Sunday, congregants at Honolulu's Westminster Cathedral, the Kawaiaha'o Church, sing this hymn, known as Ke Aloha O Ka Haku, in alternating verses of Hawaiian and English. It is a reminder of the last Hawaiian monarch's faith and her ability to forgive her enemies. During the year, the church holds a few "Ali'i" services to remember the Kingdom of Hawaii's high chiefs, usually on the Sundays before their birthdays.

Today was the "Ali'i Sunday" dedicated to Queen Lili'uokalani, who was born on September 2. She was born in 1838, the same year that the Cherokees were forcibly relocated from their homelands to Indian Territory along the Trail of Tears, and she died in 1917, long after Hawaii had been annexed to the United States. But she remains deeply alive to Hawaiians. So I decided to learn more about how some Hawaiians feel about their last queen at today's service.

By eight in the morning, even though it was drizzling in downtown Honolulu, the front doors to the church as well as the side doors were flung wide open, allowing the trade winds that had kept Honolulu cool in recent days flow through. Members of the Royal Hawaiian Societies gathered on the lawn near the steps, some men wearing red and yellow capes, a group of women dressed entirely in ankle-length black gowns, most with black gloves and hats as well – brightened only by the orange lei they wore around their necks.

Royal Societies gathered to honor the queen

Another group wore all white versions of the holoku, the modest, full-length gown introduced by the missionaries, shortly after their arrival in 1820. More than a hundred children and family members who've benefited from the Queen's financial legacy – the Lili'uokalani Trust and the Children's Center it helps fund – also attended.

Near the altar stood a stood a framed black and white photo of the Queen as a young woman, her image slightly faded with time yet brightened by the dozen or so flower garlands surrounding it. The photographer captured her at a moment when she seemed to be gazing thoughtfully at something off to the side.

After the service, which some people celebrated barefoot in the more relaxed Hawaiian style, I had a chance to meet the Lili'uokalani Trust's Chairman, Thomas Ka'auwai Kaulukukui, Jr., Trustee Claire Asam, and Ben Henderson, who is President and Executive Director of the Children's Center.

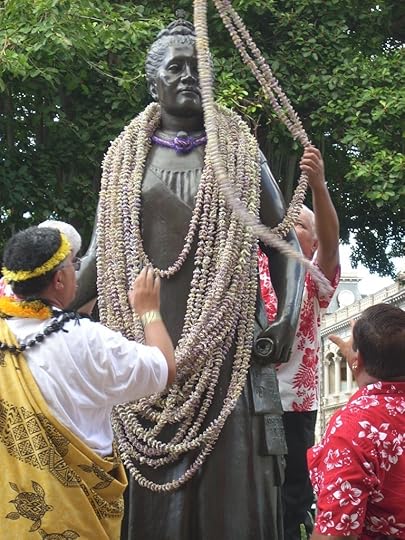

Walking over together to the statue of the Queen that stands with her back to 'Iolani Palace and faces Hawai'i's modern legislature building. Like all Hawaiians, the deposed queen became a U.S. citizen when Hawai'i became a U.S. Territory in 1900.

I asked Thomas Kaulukukui why he felt the queen was able to forgive her enemies, considering that – as the Kahu (or Rev.) Teruo Kawata in his sermon put it, they'd "dethroned her and took away her nation…" but, even so, "The queen called on her people to forgive."

He replied that he felt she was a deeply Christian woman who was also a realist – time had moved on, and though she continued to try to win back her nation even after the overthrow, she also did not allow herself to become bitter or to give up. In the same spirit of aloha, he handed me a delicate lavender-colored lei, made of the crown flowers that the Queen loved so much, so that I could join the ceremony to honor her, as a member of one of Hawaii's civic societies took it from me and gently draped the garland of flowers over her outstretched hand.

Adorning the queen's statue with crown-flower lei