Julia Flynn Siler's Blog, page 10

November 11, 2011

“The Descendants” at the Napa Valley Film Festival

Opening night at the inaugural Napa Valley Film Festival began with a walk along a red carpet into the city’s refurbished Napa Valley Opera House, a grand name for a frontier theater dating back to 1880. Screen actors, a few industry executives, and a good sampling of Napa locals (some dressed glamorously in boas and satin evening gowns, others in work boots and down vests) sipped on wine and nibbled ice cream lollipops from Napa’s Eiko restaurant.

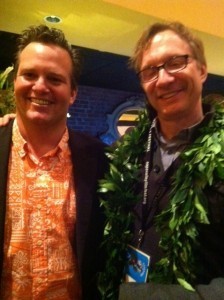

Catherine Thorpe, who helped research both The House of Mondavi and Lost Kingdom, joined me at the opening reception, where we quickly spotted a bespectacled man wearing a lei, or garland, of green leaves. Making our way through the crowd, we introduced ourselves.

He was Jim Burke, the producer of that evening’s lead film, The Descendants. A down-to-earth and engaging man, he told us that author Kaui Hart Hemmings had sent him her novel before it was published in 2007 and read it over a single weekend. As father himself, he was convinced that her dark comedy about a father struggling to cope with his two daughters following an accident that left their mother in a coma would make a great movie, with its themes of isolation, betrayal, and forgiveness.

Jon McManus, who plays the role of “cousin six” in The Descendants and Jim Burke, the film’s producer, at the inaugural Napa Valley Film Festival on November 10, 2011

Approaching the project almost like a documentary, both he and Payne traveled to Honolulu nine months or so before shooting began. Once there, they were guided by a number of well-known locals, including author Hemmings, historian and author Gavan Daws, and University of Hawaii law professor Randall W. Roth. Opening night in Napa, Burke was accompanied by Jon McManus, who played “cousin six” in the film. They were his “tour guides through Honolulu society,” he said.

Daws, the author of many very fine books about Hawaii, including Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands, helped by reading the script and by providing his thoughts with the filmmakers on music, which is entirely by Hawaiian artists. Indeed, one of the songs on the soundtrack was written by Liliuokalani, Hawaii’s last queen.

Roth, the co-author of Broken Trust: Greed, Mismanagement, & Political Manipulation at America’s Largest Charitable Trust, provided guidance on trust law to the filmmakers, particularly on the somewhat arcane subject of the rule against perpetuities (which is important to the plot, which involves the descendants of a Hawaiian princess and haole (white or foreign) banker who’ve inherited a piece of land, which is held in trust. They must decide whether to sell it because the trust itself, under the rule against perpetuities, must be wound down by a set date.

The back-story of a trust with large land holding in Hawaii echoes the realities of land and power in Hawaii. Although Kaui told me that she did not base her novel on any one real family, she drew from a number of family trusts which were in the news around the time she was writing her book. Indeed, large amounts of land are still held in Hawaii by what are known as the Ali’i trusts – the charitable organizations set up, in most cases, more than a century ago to hold the land and other assets of Hawaiian royalty. The most prominent of these was known as the Bishop Estate, until the scandal revealed in Broken Estate hit it and it renamed itself Kamehameha Schools.

Perhaps the strongest echo of a situation facing the George Clooney character was faced in real life a few years back by the trustees of Hawaii’s Campbell Estate. Under the terms of the trust, the 107-year-old Campbell Estate was required to dissolve in January of 2007, twenty years after the last death of the direct descendants who had been alive at the time of the trust’s creation. Some of the heirs took large cash pay-outs, according to an account in the Honolulu Advertiser (now the Honolulu Star Advertiser), while others chose instead to roll their assets into a new national real estate entity, the San Francisco-based James Campbell Co. LLC.

Professor Roth says there have been perhaps a half dozen family trusts in Hawaii in recent years that have faced this same situation. The rule against perpetuities only applies to trusts where the beneficiaries are individuals, rather than charities – as in the case of the Ali’i trusts. “It’s a very realistic scenario,” he says about the decision facing the fictional Matt King character, played by George Clooney, and his cousins. “I was impressed that Jim and Alexander were so concerned about getting the details right, even small details that most people wouldn’t be aware of.” The filmmakers credited both Professor Roth and author Gavan Daws at the end of the film.

Matt King is a descendant of a Hawaiian princess, who was a member of the powerful Kamehameha dynasty, and an American banker. It’s a fictional lineage similar to that of founder of what was formerly known as the Bishop Estate — the American banker Charles Reed Bishop, who married the Hawaiian Princess Bernice Pauahi.

What producer Jim Burke calls the “link in the chain” scene in which Matt King looks at a series of black and white photos of his ancestors. He’s asking himself whether he’s doing the right thing by selling the land that had been entrusted to his family. It’s a question that many of the descendants of Hawaii’s old families surely must have asked themselves in recent years, as much of what makes Hawaii so achingly beautiful has disappeared beneath resort developments and condominiums. These are the same people whose ancestors came to Hawaii to do good and ended up doing very well indeed.

After having spent the past four years examining Hawaii’s history of closely intertwined families and fortunes, this movie resonates with me on many different levels. Go see it. It’s not only a very funny and moving family story, but also a very astute portrait of modern day Hawaii.

"The Descendants" at the Napa Valley Film Festival

Opening night at the inaugural Napa Valley Film Festival began with a walk along a red carpet into the city's refurbished Napa Valley Opera House, a grand name for a frontier theater dating back to 1880. Screen actors, a few industry executives, and a good sampling of Napa locals (some dressed glamorously in boas and satin evening gowns, others in work boots and down vests) sipped on wine and nibbled ice cream lollipops from Napa's Eiko restaurant.

Catherine Thorpe, who helped research both The House of Mondavi and Lost Kingdom, joined me at the opening reception, where we quickly spotted a bespectacled man wearing a lei, or garland, of green leaves. Making our way through the crowd, we introduced ourselves.

He was Jim Burke, the producer of that evening's lead film, The Descendants. A down-to-earth and engaging man, he told us that author Kaui Hart Hemmings had sent him her novel before it was published in 2007 and read it over a single weekend. As father himself, he was convinced that her dark comedy about a father struggling to cope with his two daughters following an accident that left their mother in a coma would make a great movie, with its themes of isolation, betrayal, and forgiveness.

Jon McManus, who plays the role of "cousin six" in The Descendants and Jim Burke, the film's producer, at the inaugural Napa Valley Film Festival on November 10, 2011

Approaching the project almost like a documentary, both he and Payne traveled to Honolulu nine months or so before shooting began. Once there, they were guided by a number of well-known locals, including author Hemmings, historian and author Gavan Daws, and University of Hawaii law professor Randall W. Roth. Opening night in Napa, Burke was accompanied by Jon McManus, who played "cousin six" in the film. They were his "tour guides through Honolulu society," he said.

Daws, the author of many very fine books about Hawaii, including Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands, helped by reading the script and by providing his thoughts with the filmmakers on music, which is entirely by Hawaiian artists. Indeed, one of the songs on the soundtrack was written by Liliuokalani, Hawaii's last queen.

Roth, the co-author of Broken Trust: Greed, Mismanagement, & Political Manipulation at America's Largest Charitable Trust, provided guidance on trust law to the filmmakers, particularly on the somewhat arcane subject of the rule against perpetuities (which is important to the plot, which involves the descendants of a Hawaiian princess and haole (white or foreign) banker who've inherited a piece of land, which is held in trust. They must decide whether to sell it because the trust itself, under the rule against perpetuities, must be wound down by a set date.

The back-story of a trust with large land holding in Hawaii echoes the realities of land and power in Hawaii. Although Kaui told me that she did not base her novel on any one real family, she drew from a number of family trusts which were in the news around the time she was writing her book. Indeed, large amounts of land are still held in Hawaii by what are known as the Ali'i trusts – the charitable organizations set up, in most cases, more than a century ago to hold the land and other assets of Hawaiian royalty. The most prominent of these was known as the Bishop Estate, until the scandal revealed in Broken Estate hit it and it renamed itself Kamehameha Schools.

Perhaps the strongest echo of a situation facing the George Clooney character was faced in real life a few years back by the trustees of Hawaii's Campbell Estate. Under the terms of the trust, the 107-year-old Campbell Estate was required to dissolve in January of 2007, twenty years after the last death of the direct descendants who had been alive at the time of the trust's creation. Some of the heirs took large cash pay-outs, according to an account in the Honolulu Advertiser (now the Honolulu Star Advertiser), while others chose instead to roll their assets into a new national real estate entity, the San Francisco-based James Campbell Co. LLC.

Professor Roth says there have been perhaps a half dozen family trusts in Hawaii in recent years that have faced this same situation. The rule against perpetuities only applies to trusts where the beneficiaries are individuals, rather than charities – as in the case of the Ali'i trusts. "It's a very realistic scenario," he says about the decision facing the fictional Matt King character, played by George Clooney, and his cousins. "I was impressed that Jim and Alexander were so concerned about getting the details right, even small details that most people wouldn't be aware of." The filmmakers credited both Professor Roth and author Gavan Daws at the end of the film.

Matt King is a descendant of a Hawaiian princess, who was a member of the powerful Kamehameha dynasty, and an American banker. It's a fictional lineage similar to that of founder of what was formerly known as the Bishop Estate — the American banker Charles Reed Bishop, who married the Hawaiian Princess Bernice Pauahi.

What producer Jim Burke calls the "link in the chain" scene in which Matt King looks at a series of black and white photos of his ancestors. He's asking himself whether he's doing the right thing by selling the land that had been entrusted to his family. It's a question that many of the descendants of Hawaii's old families surely must have asked themselves in recent years, as much of what makes Hawaii so achingly beautiful has disappeared beneath resort developments and condominiums. These are the same people whose ancestors came to Hawaii to do good and ended up doing very well indeed.

After having spent the past four years examining Hawaii's history of closely intertwined families and fortunes, this movie resonates with me on many different levels. Go see it. It's not only a very funny and moving family story, but also a very astute portrait of modern day Hawaii.

The Descendants at the Napa Valley Film Festival

Opening night at the inaugural Napa Valley Film Festival began with a walk along a red carpet into the city's refurbished 1880 Napa Valley Opera House. Screen actors, a few industry executives, and a good sampling of Napa locals (some dressed glamorously in boas and satin evening gowns, others in work boots and down vests) sipped on wine and nibbled ice cream lollipops from Napa's Eiko restaurant.

Catherine Thorpe, who helped research both The House of Mondavi and Lost Kingdom for me, joined me at the opening reception, where we quickly spotted a bespectacled man wearing a lei, or garland, of green leaves. Making our way through the crowd, we introduced ourselves.

He was Jim Burke, the film's producer. A down-to-earth and engaging man, he told us that Kaui had sent him her novel before it was published in 2007 and read it over a single weekend. As father

himself, he was convinced that her dark comedy about a father struggling to cope with his two daughters following an accident that left their mother in a coma would make a great movie, with its themes of isolation, betrayal, and forgiveness.

Jon McManus, who plays the role of "cousin six" in The Descendants and Jim Burke, the film's producer, at the inaugural Napa Valley Film Festival on November 10, 2011

Approaching the project almost like a documentary, both he and Payne travelled to Honolulu nine months or so before shooting began. Once there, they were guided by a number of well-known locals, including author Hemmings, historian and author Gavan Daws, and University of Hawaii law professor Randall W. Roth. Opening night in Napa, Burke was accompanied by the author's cousin, Jon McManus, who played cousin six in the film. They were his "tour guides through Honolulu society," he said.

Daws, the author of many very fine books about Hawaii, including Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands, had helped by reading the script and by providing his

thoughts with them on the film's music, which is entirely by Hawaiian artists. Indeed, one of the songs on the soundtrack was written by Liliuokalani, Hawaii's last queen.

Roth, the co-author of Broken Trust: Greed, Mismanagement, & Political Manipulation at America's Largest Charitable Trust, provided guidance on trust law to the

filmmakers, particularly on the somewhat arcane subject of the rule against perpetuities (which is important to the plot, which involves the descendants of a Hawaiian

princess and haole (white or foreign) banker who've inherited a piece of land, which is held in trust. They must decide whether to sell it because the trust itself, under the rule against

perpetuities, must be wound down by a set date.

The back-story of a trust with large land holding in Hawaii echoes the realities of land and power in Hawaii. Although Kaui told me that she did not base her novel on any one real family, she drew from a number of trusts which were in the news around the time she was writing her book. Indeed, large amounts of land are still held in Hawaii by what are known as the Ali'i trusts – the charitable organizations set up, in most cases, more than a century ago to hold the land and other assets of Hawaiian royalty. The most prominent of these was known as the Bishop Trust,

until the scandal revealed in Broken Trust hit it and it renamed itself Kamehameha Schools.

Perhaps the strongest echo of a situation facing the George Clooney character was faced in real life a few years back by the trustees of Hawaii's Campbell Estate. Under the terms of

the trust, the Campbell Estate was required to dissolve in January of 2007, twenty years after the death of the last direct descendant of the trust's founder. Some of the heirs took large cash pay-outs, according to an account in the Honolulu Advertiser, while others chose instead to roll their assets into a new real estate entity, the James Campbell Co. LLC.

Professor Roth says there have been perhaps a half dozen family trusts in Hawaii in recent years that have faced this same situation. The rule of perpetuities only applies to trusts where the beneficiaries are individuals, rather than charities – as in the case of the Ali'i trusts. "It's a very realistic scenario," he says. "I was impressed that Jim and Alexander

were so concerned about getting the details right, even small details that most people wouldn't be aware of."

Matt King, the character played by George Clooney, is a descendant of a Hawaiian princess, who was a member of the powerful Kamehameha dynasty, and an American banker.

It's a fictional lineage similar to that of founders of what was formerly known as the Bishop Trust — Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop and her husband, banker Charles R. Reed.

What producer Jim Burke calls the "link in the chain" scene in which Matt King looks at a series of black and white photos of his ancestors. He seems to be questioning whether he's doing the right thing by selling the land that had been entrusted to him. It's a question that many of the descendants of Hawaii's founding families surely must have asked themselves in recent years, as much of what makes Hawaii so achingly beautiful has disappeared beneath resort developments and condominiums.

After having spent the past four years researching and writing about Hawaii's closely intertwined history of powerful families and vast fortunes, this movie resonates with me on many different levels. Go see it — and not just because George looks great in a swimsuit.

November 1, 2011

My Conversion to Liking Breadfruit: “I’ve been ulu-cized!”

When I arrived at a garden near the town of Captain Cook, on the big island of Hawaii, to attend a Breadfruit Festival in late September, I was a skeptic.

Prize-winning breadfruit tart at the inaugural Breadfruit Festival: Photo by Julia Flynn Siler

Beforehand, I’d talked to one of the world’s leading experts, the Breadfruit Institute’s Director, Diane Ragone PhD., who had told me she hadn’t cared for it when she first tried it. I’d learned from the Breadfruit Institute’s own website about the difficulties faced by Captain Bligh in fulfilling his mission of introducing breadfruit plants to the Caribbean (during the infamous mutiny on the bounty, the mutineers tossed the trees overboard.) I’d even found a discussion on the gardening website GardenWeb under lists of the “five WORST tropical fruits,” with one writer pronouncing breadfruit “nauseous.”

Diane Ragone, PhD., Director of the Breadfruit Institute, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

But when I arrived at the festival that day, my conversion began. Fragrant smoke rose from a fire circle where breadfruit roasted on burning coconut shells. (Watch video here) Women mashed the fruit with a pestle to make breadfruit poi, a traditional porridge-like food. The marvelously vivacious Chef Olelo pa’a Faith Ogawa, a Hawaii-born private chef, demonstrated several recipes to a rapt audience, passing out samples which were appreciatively wolfed down. A long line of people waited patiently that day to sample a special breadfruit lunch.

Chef Olelo pa’a Faith Ogawa, a Hawaii-born private chef, doing a cooking demonstration at the Breadfruit Festival, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

I’d bought a ticket to try a half dozen of the dishes entered into the cooking contest. To my surprise, several of them were delicious.

The one that comes immediately to mind was a recipe for Ulu Tart, (ulu is the Hawaiian word for breadfruit,) which was made with two cups of cooked breadfruit, one cup of fresh coconut milk, Lehua honey, and a macadamia nut crust. It was superb – though the breadfruit itself was pretty much disguised by the coconut milk and honey.

I also tried a breadfruit casserole made with three different kinds of cheese as well as a very unusual ulu salad with cucumbers and dill, which, along with the tart, was also a prize-winner. I had the pleasure of meeting the person who came up with the salad recipe after he accepted his award for it.

His name was Nader “Nanoa” Parsia, who grew up in Persia before it became Iran. In the many years that he has lived on the islands, he told me he’d come to embrace the cooking and foods of his adopted home Hawaii. Smiling widely, he said “Some people have been baptized. Today, I’ve been ulu-cized!”

Nader “Nanoa” Parsia holding up his awards for breadfruit dishes, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

I felt the same way: I became a breadfruit believer that day too and greatly admire the work that Diane Ragone and her colleagues at the Breadfruit Institute as well as the Hawaii Homegrown Food Network are doing to introduce people to this nutritious food, particularly at a time when so many people are hungry. Mahalo for introducing me to it. I only wish I could have brought one of these beautiful trees home with me to California ~

Breadfruit tree sales at the inaugural Breadfruit Festival in Kona, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

My Conversion to Liking Breadfruit: "I've been ulu-cized!"

When I arrived at a garden near the town of Captain Cook, on the big island of Hawaii, to attend a Breadfruit Festival in late September, I was a skeptic.

Prize-winning breadfruit tart at the inaugural Breadfruit Festival: Photo by Julia Flynn Siler

Beforehand, I'd talked to one of the world's leading experts, the Breadfruit Institute's Director, Diane Ragone PhD., who had told me she hadn't cared for it when she first tried it. I'd learned from the Breadfruit Institute's own website about the difficulties faced by Captain Bligh in fulfilling his mission of introducing breadfruit plants to the Caribbean (during the infamous mutiny on the bounty, the mutineers tossed the trees overboard.) I'd even found a discussion on the gardening website GardenWeb under lists of the "five WORST tropical fruits," with one writer pronouncing breadfruit "nauseous."

Diane Ragone, PhD., Director of the Breadfruit Institute, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

But when I arrived at the festival that day, my conversion began. Fragrant smoke rose from a fire circle where breadfruit roasted on burning coconut shells. (Watch video here) Women mashed the fruit with a pestle to make breadfruit poi, a traditional porridge-like food. The marvelously vivacious Chef Olelo pa'a Faith Ogawa, a Hawaii-born private chef, demonstrated several recipes to a rapt audience, passing out samples which were appreciatively wolfed down. A long line of people waited patiently that day to sample a special breadfruit lunch.

Chef Olelo pa'a Faith Ogawa, a Hawaii-born private chef, doing a cooking demonstration at the Breadfruit Festival, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

I'd bought a ticket to try a half dozen of the dishes entered into the cooking contest. To my surprise, several of them were delicious.

The one that comes immediately to mind was a recipe for Ulu Tart, (ulu is the Hawaiian word for breadfruit,) which was made with two cups of cooked breadfruit, one cup of fresh coconut milk, Lehua honey, and a macadamia nut crust. It was superb – though the breadfruit itself was pretty much disguised by the coconut milk and honey.

I also tried a breadfruit casserole made with three different kinds of cheese as well as a very unusual ulu salad with cucumbers and dill, which, along with the tart, was also a prize-winner. I had the pleasure of meeting the person who came up with the salad recipe after he accepted his award for it.

His name was Nader "Nanoa" Parsia, who grew up in Persia before it became Iran. In the many years that he has lived on the islands, he told me he'd come to embrace the cooking and foods of his adopted home Hawaii. Smiling widely, he said "Some people have been baptized. Today, I've been ulu-cized!"

Nader "Nanoa" Parsia holding up his awards for breadfruit dishes, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

I felt the same way: I became a breadfruit believer that day too and greatly admire the work that Diane Ragone and her colleagues at the Breadfruit Institute as well as the Hawaii Homegrown Food Network are doing to introduce people to this nutritious food, particularly at a time when so many people are hungry. Mahalo for introducing me to it. I only wish I could have brought one of these beautiful trees home with me to California ~

Breadfruit tree sales at the inaugural Breadfruit Festival in Kona, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

My Conversion to Liking Breadfruit: "I've been ula-cized!"

When I arrived at a garden near the town of Captain Cook, on the big island of Hawaii, to attend a Breadfruit Festival in late September, I was a skeptic.

Prize-winning breadfruit tart at the inaugural Breadfruit Festival: Photo by Julia Flynn Siler

Beforehand, I'd talked to one of the world's leading experts, the Breadfruit Institute's Director, Diane Ragone PhD., who had told me she hadn't cared for it when she first tried it. I'd learned from the Breadfruit Institute's own website about the difficulties faced by Captain Bligh in fulfilling his mission of introducing breadfruit plants to the Caribbean (during the infamous mutiny on the bounty, the mutineers tossed the trees overboard.) I'd even found a discussion on the gardening website GardenWeb under lists of the "five WORST tropical fruits," with one writer pronouncing breadfruit "nauseous."

Diane Ragone, PhD., Director of the Breadfruit Institute, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

But when I arrived at the festival that day, my conversion began. Fragrant smoke rose from a fire circle where breadfruit roasted on burning coconut shells. (Watch video here) Women mashed the fruit with a pestle to make breadfruit poi, a traditional porridge-like food. The marvelously vivacious Chef Olelo pa'a Faith Ogawa, a Hawaii-born private chef, demonstrated several recipes to a rapt audience, passing out samples which were appreciatively wolfed down. A long line of people waited patiently that day to sample a special breadfruit lunch.

Chef Olelo pa'a Faith Ogawa, a Hawaii-born private chef, doing a cooking demonstration at the Breadfruit Festival, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

I'd bought a ticket to try a half dozen of the dishes entered into the cooking contest. To my surprise, several of them were delicious.

The one that comes immediately to mind was a recipe for Ulu Tart, (ulu is the Hawaiian word for breadfruit,) which was made with two cups of cooked breadfruit, one cup of fresh coconut milk, Lehua honey, and a macadamia nut crust. It was superb – though the breadfruit itself was pretty much disguised by the coconut milk and honey.

I also tried a breadfruit casserole made with three different kinds of cheese as well as a very unusual ulu salad with cucumbers and dill, which, along with the tart, was also a prize-winner. I had the pleasure of meeting the person who came up with the salad recipe after he accepted his award for it.

His name was Nader "Nanoa" Parsia, who grew up in Persia before it became Iran. In the many years that he has lived on the islands, he told me he'd come to embrace the cooking and foods of his adopted home Hawaii. Smiling widely, he said "Some people have been baptized. Today, I've been ula-cized!"

Nader "Nanoa" Parsia holding up his awards for breadfruit dishes, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

I felt the same way: I became a breadfruit believer that day too and greatly admire the work that Diane Ragone and her colleagues at the Breadfruit Institute as well as the Hawaii Homegrown Food Network are doing to introduce people to this nutritious food, particularly at a time when so many people are hungry. Mahalo for introducing me to it. I only wish I could have brought one of these beautiful trees home with me to California ~

Breadfruit tree sales at the inaugural Breadfruit Festival in Kona, photo by Julia Flynn Siler

October 30, 2011

Meeting the Alice Waters of Hawai'i: Chef Alan Wong

"Be sure to eat on the flight" the oft-repeated joke goes, "because the airplane meal is likely to be the best you'll have on your trip to Hawai'i."

Honolulu magazine's October cover story on Hawaiian regional cuisine traces that jibe about the Aloha State's supposed lack of gourmet dining to Bon Appetit's former editor-in-chief Barbara Fairchild, who advised readers to enjoy the meal on the plane, because it was the best food they'd get on a Hawai'i vacation.

These days, visitors with low culinary expectations about the islands are in for a surprise. I took a dozen or so trips to the Hawai'i over the past four years to research Lost Kingdom and, each time, enjoyed some terrific food, usually at hole-in-the-walls near downtown Honolulu, within easy walking distance of the Hawai'i State Archives.

Chef Alan Wong wins an award for his second cookbook, The Blue Tomato

But my most memorable meals required short drives from downtown Honolulu: grilled garlic ahi at Irifune on Kapahulu Ave., a pork noodle soup at a Hawai'ian Vietnamese restaurant called Hale Vietnam, off Waialae Ave., and lemon pepper shrimp from Macky's Sweet Shrimp Truck on Oahu's north shore. I generally ate at modestly priced places, but did splash out once for the Sunday brunch at the Halekulani in Waikiki, where both the food and the ocean view were spectacular.

I'd heard of Alan Wong, who has cooked for President Obama on a number of occasions, as well as his Pineapple Room in Honolulu's Ala Moana Center, but had never made it there during one of my trips. But recently the James Beard Award-winning chef made it to San Francisco, courtesy of Watermark Publishing and the Hawai'i Visitors & Convention bureau as part of a Taste Hawai'i Tour of big west coast cities.

On one evening of his tour, a group of writers from the San Francisco Bay Area were invited to meet Chef Wong, who prepared a tasting menu for us. A broad shouldered man wearing chef's whites, he was in fine form and sipping towards the end of the evening on a Napa cabernet. Accompanying him on the tour were a shrimp farmer from Kauai, a tomato grower from Ho Farms in Kahuku, and an agriculturalist working for the Dole Food Company, which is now experimenting with growing cacao in former pineapple fields.

Two decades ago, Alan Wong was one of twelve chefs who banded together to create a locavore movement they called Hawai'i Regional Cuisine, focusing on using locally-grown vegetables, milk and dairy products from local dairies, and seafood and beef from the islands. In recent years, he — like Chez Panisse's Alice Waters — has thrown his support behind the islands' local producers and helped teach school children about food.

Regional cuisine was a movement catching on around the country at the time (in the early 1990s, I wrote a story about Midwestern chefs doing the same thing and, of course, the Berkeley's own Alice Waters helped kick it off in the San Francisco Bay Area decades earlier.) The efforts of these pioneering Hawaiian chefs come at a time when the state is grappling with the question of how to reduce its dependence on foods imports.

That, in turn, is the sad legacy of the islands' economic transformation from a time when native Hawaiians supported themselves by planting taro patches and building fish ponds. With the arrival of enterprising foreigners, these were subsumed during the nineteenth century by vast sugar plantations.

Now, the sugar industry is almost gone and more than a century of planting vast swaths of the islands with a single crop have taken a heavy environmental toll. As a result, Hawai'i is left with an alarming dependence on imported food. Encouraging local farmers is a step in the right direction. Yet, many islanders simply can't afford $3 tomatoes and $12.50 a pound frozen shrimp. Hence, much of the local food ends up in expensive restaurants catering to tourists.

Chef Wong, who attended a government hosted conference on food security for Hawai'i recently, told me that if a natural or man-made disaster occurred and both container shipments and air cargo were halted, the Hawaiian islands would last just six days before running out of food. Apec Leaders meeting in November in Hawai'i are likely to discuss this and other food security issues.

No doubt, the food at the Apec meeting, hosted by the East-West Center at the University of Hawai'i will be delicious. And despite talk of potential food shortages in the case of an emergency, the evening with Chef Wong in San Francisco in late October was one of abundance, with tastes of more than a dozen of dishes from his new cookbook, The Blue Tomato.

Some highlights: a Hanaoka Farms ahi cerviche with pickled jalapeno and purple sweet potato, "Char Siu" lamb chops with hoisin-sriracha-five-spice greek yogurt, and a dish chef calls "Da Bag" – Kalua pig and steamed clams with shrimp, and lobster. Click here to watch the video of Chef Wong preparing "Da Bag."

The chocolate crunch bars made from Dole's Waialua Estate on the north shore of Oahu were memorable, too (the chocolate is available at Whole Foods stores in Hawai'i) as was his pineapple shave ice. A lovely evening that raised some thought-provoking questions about the growing movement in Hawai'i to support local agriculture and talented home-grown chefs.

Chef Alan Wong: Tasting Hawai'i

"Be sure to eat on the plane" the old saw goes, "because the meal will be the best you'll have on your trip to Hawai'i."

Honolulu magazine's October cover story on Hawaiian regional cuisine traces that well-known jibe about the Aloha State's supposed lack of gourmet dining to Bon Appetit's former editor-in-chief Barbara Fairchild, who advised readers to enjoy the meal on the plane, because it was the best food they'd get on a Hawai'i vacation.

These days, visitors with low culinary expectations about the islands might be happily surprised. I took a dozen or so trips to the Hawai'i over the past four years to research Lost Kingdom and, each time, found myself discovering some terrific food – often in holes-in-the-wall near downtown Honolulu, within easy walking distance of the Hawai'i State Archives.

Chef Alan Wong wins an award for his second cookbook, The Blue Tomato

Most memorable: grilled garlic ahi at Irifune on Kapahulu Ave. in Honolulu, a pork noodle soup at a Hawai'ian Vietnamese restaurant called Hale Vietnam, and lemon pepper shrimp from Macky's Sweet Shrimp Truck on Oahu's north shore. I generally ate at modest places, but did splash out once for the Sunday brunch at the Halekulani at Waikiki: both the food and the ocean view were spectacular.

I'd heard of Alan Wong's Pineapple Room, but never made it there during one of my trips. But recently the James Beard Award-winning chef made it to San Francisco, courtesy of Watermark Publishing and the Hawai'i Visitors & Convention bureau as part of a Taste Hawai'i Tour of big west coast cities.

One evening, a group of writers from the San Francisco Bay Area were invited to meet Chef Wong, who prepared a tasting menu for us. A broad shouldered man wearing chef's whites, he was in fine form and sipping towards the end of the evening on a Napa cabernet. Accompanying him on the tour were a shrimp farmer from Kauai, a tomato grower from Ho Farms in Kahuku, and an agriculturalist working for the Dole Food Company, which is now experimenting with growing cacao in former pineapple fields.

Alan Wong was part of a group of twelve chefs who banded together ten years ago to create a locavore movement they called Hawai'i Regional Cuisine, focusing on using locally-grown vegetables, milk and dairy products from local dairies, and seafood and beef from the islands.

Regional cuisine was a movement going on around the country at the time (in the early 1990s, I wrote a story about Midwestern chefs doing the same thing.) Yet the decade-long efforts of these Hawaiian chefs come at a time when the state is grappling with the question of how to reduce its dependence on foods imports.

That, in turn, is the sad legacy of the islands' economic transformation from a time when native Hawaiians supported themselves by planting taro patches and building fish ponds. With the arrival of enterprising foreigners, these were subsumed during the nineteenth century by vast sugar plantations.

Now, the sugar industry is almost gone and more than a century of planting vast swaths of the islands with a single crop have taken a heavy environmental toll. As a result, Hawai'i is left with an alarming dependence on imported food. Yet, the irony is that many island locals simply can't afford $3 tomatoes and $12.50 a pound frozen shimp. Hence, much of the local food ends up in expensive restaurants catering to tourists.

Chef Wong, who attended a government hosted conference on food security for Hawai'i recently, told me that if a natural or man-made disaster occurred and both container shipments and air cargo were halted, the Hawaiian islands would last just six days before running out of food. Apec Leaders meeting in November in Hawai'i are likely to discuss this and other food security issues.

No doubt, the food at the Apec meeting will be delicious. And despite talk of food shortages, the evening with Chef Wong was one of abundance, with tastes of more than a dozen of dishes from his new cookbook, The Blue Tomato.

Some highlights: a Hanaoka Farms ahi cerviche with pickled jalapeno and purple sweet potato, "Char Siu" lamb chops with hoisin-sriracha-five-spice greek yogurt, and a dish chef calls "Da Bag" – Kalua pig and steamed clams with shrimp, lobster, with Kauai shrimp thrown in for good measure. Click here to watch the video.

The chocolate crunch bars made from Dole's Waialua Estate on the north shore of Oahu were memorable, too (the chocolate is available at Whole Foods stores in Hawai'i) and the pineapple shave ice was other-worldly. A lovely evening that raised some thought-provoking questions about whether Hawai'i can continue supporting local agriculture and home-grown chefs.

October 24, 2011

How Novelist Kaui Hart Hemmings landed a role opposite George Clooney in "The Descendants"

The statistics are daunting: less than two percent of all the books optioned for the screen ever enter production. Far fewer make it into theaters. My first book, The House of Mondavi was optioned twice, but never came close to becoming a movie.

That's why it's been a vicarious thrill to watch Kaui Hart Hemmings' first novel, The Descendants, approach its release date of Nov. 18th as a movie from Fox Searchlight.

Novelist Kaui Hart Hemmings, author of "The Descendants"

The Descendants was Kaui's debut novel. A dark comedy about a dysfunctional family, it was first published in 2007 to critical acclaim. The New York Times called it "refreshingly wry."

Around the time her book came out, Kaui was working out of the San Francisco Writers' Grotto and writing a hilarious blog called "How to Party with an Infant." (Check out her excruciatingly funny post on bikini waxing, if you dare!) Her collection of short stories, House of Thieves, is stunning, particularly the title story.

I first met Kaui when I moderated a panel at Book Group Expo in San Jose. The theme of our panel was fractured families (under the title "Tales of Ruin and Renewal, even Triumph!") I had just come out with my book on the Mondavis, and the panel also included Rich Cohen, who wrote the 2006 book on his family, Sweet and Low.

The Descendants was optioned by Alexander Payne, the director of the unexpected hit, "Sideways." Originally, Payne had not planned to direct the film. But, in chatting with Kaui by phone last week, she told me he'd emailed her sometime in 2008 to let her know he'd decided to direct it himself. He also offered to meet her in Hawaii that coming weekend.

"I was nervous about what wine to order," Kaui told me. Sideways was the 2004 movie about a troubled oenophile, played by Paul Giamatti, who takes a road trip through Santa Barbara's wine country involving too much wine and some romantic misadventures.

Kaui and her husband were headed to a birthday party the next day for Kaui's aunt, held at her grandmother's house. She invited Payne as well as set designer Jane Ann Stewart along "to hang out and see how these particular locals party." That was the start of a friendship, as Kaui helped Payne scout locations, particularly after he decided to rent a home in the lush Manoa Valley, a few miles inland of downtown Honolulu, for about six months.

"He almost approached it as if he were making a documentary," she says. He met with the island's big landowners, visited the Outrigger Club, a key setting in the novel, and met Kaui's famous step-father, the champion surfer-turned-politician Fred Hemmings, Jr. (Kaui was adopted by him when she was 11 years old.)

"I had expected someone to just parachute in and write the screenplay," she says, but found that Payne took his task of translating her novel, set in contemporary Hawaii, seriously. The novelist and director struck up a friendship and Kaui ended up reading the screenplay and reviewing the casting videos, as well as discussing details down to the wardrobes that key characters would wear.

"I felt like I haven't had the typical experience" of a novelist whose book becomes a movie, Kaui told me. She was free to visit the set every day, if she wanted to, and she ended up landing a bit part as the secretary of Matt King, the character descended from Hawaiian royalty and sugar plantation owners that George Clooney plays.

Her big moment? "Matt, your cousins are here." Thinking back on it, she recalls that she needed to work on her intonation and deliver the line more naturally. "It took a long time to say a few lines," she says.

To play the part, the film's hairdresser styled her hair and its makeup artist brushed rouge onto her cheeks and mascara onto her eyelashes. Someone from the wardrobe department picked her outfit for her. It felt "surreal" to her to be a non-actor playing a role in a movie modeled after her real world.

"It was just me and George in this room. What am I doing here with George Clooney, I kept asking myself, I'm not supposed to be here, but thanks!"

She, her husband, and her mother were hired as extras for a party scene in the movie, playing themselves. Scenes that took place at the Outrigger were moved to the Elks Club next door, since the Outrigger wouldn't permit Payne's crew to film there, Kaui says.

But aside from not having the party at the club itself, other details were spot on – including party-goers dressed in aloha attire and the food including poke (a raw tuna salad, usually made with soy sauce, green onions, and sesame oil) and chicken long rice, a dish brought to the islands by Chinese workers contracted to work in the sugar fields and a Hawaiian luau staple.

The movie's production designer, Jane Stewart, credits Kaui for helping her get the local details just right. One example was that Kaui introduced her to the pune'e, the casual Hawaiian daybeds often used as sprawling sofas.

Much of The Descendants' soundtrack is by local musicians, including slack key guitarist Gabby Pahinui, Keola Beamer, Ozzie Kotani and Daniel Ho, as well as many others. There's even a song in it written by the last queen of Hawaii, Lili'uokalani, the central character in my next book, Lost Kingdom.

Kaui's six-year-old daughter made it into the film, too, as an extra in a beach scene in Hanalei Bay. "She was very proud of the $100 she made," Kaui recalls. But that's nothing compared to what her talented mom might earn from sales of her book following the film release.

Random House has published a new edition of the book, with none other than George Clooney himself on the cover, looking thoughtfully towards his character Matt King's daughters on the beach. The word is that they've printed 80,000 copies of the paperback for their initial print run. Kaui must be getting chicken skin!

September 26, 2011

Kava in South Kona

The 'Awa plant, also known as Kava

I caught a glimpse of the sign out of the corner of my eye: "Ma's Nic Nats & Kava Stop." I made a quick U-turn on the Mamalahao Highway in South Kona and headed back, pulling across from a laundromat where children chased each other outside as their parents waited for clothes to dry.

From the outside, the kava bar didn't look like much. But it was starting to rain and I had another hour before I could check into my hotel room. So I climbed out of my car and walked in.

It was a tiny place, with perhaps 10 seats. Tending bar was Ma, the kava stop's namesake. A Hawaiian woman with a broad smile, she welcomed me in. The bar itself was made of carved mango wood, salvaged from trees cut down to make way for a new coffee plantation.

A young woman from Northern California sat on a bar stool. Her two friends, refugees from Colorado who'd moved to the islands five years ago, sat at a small table. They all held coconut shells with long straws sticking out. Sipping kava mixed with pineapple and coconut juice, they all had relaxed smiles on their faces.

"Try this" Ma told them, as she handed them a long slice of dried fish. "It real ono."

She made me the same $5.00 kava drink. It tasted good, though I later realized she'd given me a beginner's draw, nice and sweet. Within a couple of minutes, my mouth began to tingle and I started to feel light-headed. I drank more. (Kava, like coffee, is not regulated.)

I'd seen an awa plant, which the drink is made from, that morning at the Bishop Museum's Amy B. H. Greenwell Ethnobotanical Garden in South Kona,. A member of the black pepper family, roots of the kava (which is the name for it in Tonga and the Marquesas – Hawaiians call it 'awa) were traditionally chewed. Then the chewed mass was put into a bowl, mixed with water, and strained.

When the first European visitors came to the Hawaiian islands in the late eighteenth century, Polynesians would offer their drink made from the kava root to these honored guests. It also played a part in religious ceremonies as an offering to the gods.

Nowadays, machines macerate the dry roots into a fine powder which is then mixed with water. The drink's allure comes from kavalactone, a compound which acts as a relaxant or sedative, with a mild numbing effect. It doesn't seem to effect mental clarity.

When I told a new friend about my experiment with kava later that night, he laughed and described it as being "sort of like a mud Novocain drink." He and his wife had tried it in Samoa, where — to hear him tell it — the roots are ground up along with a lot of dirt, making drinking it an experience not unlike sipping from a mud puddle.

Oddly, kava bars are starting to pop up on the mainland, including one called the "Kahuna 'Awa Kava Bar" in Deerfield Beach Florida. The Yelp reviews of this place are probably more fun to read than the experience of drinking kava itself.

Oddly, kava bars are starting to pop up on the mainland, including one called the "Kahuna 'Awa Kava Bar" in Deerfield Beach Florida. The Yelp reviews of this place are probably more fun to read than the experience of drinking kava itself.

Rony, from Miami, was shocked by the price: "$25 a bowl! Is this stuff harvested by Swiss financial planners?" Another described it as tasting like "pistachio nut shells covered in dirt."

Mine actually tasted pretty good. Maybe Ma just has a better recipe. She offered my kava up with sweet aloha, giving me a warm hug goodbye. But I don't think I'll empty another coconut shell of the stuff anytime soon. I'd love to visit Ma again, but next time will just order a smoothie — hold the kava.