James Maliszewski's Blog, page 118

February 4, 2022

Raising Questions about Raising the Dead

In a comment to yesterday's post about my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, I was asked why I balked at giving player characters' access to spells like raise dead, when the game itself allows them? That's a very good question and I'm glad it was asked, because it made me explore my feelings on the matter a bit more.

In a comment to yesterday's post about my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, I was asked why I balked at giving player characters' access to spells like raise dead, when the game itself allows them? That's a very good question and I'm glad it was asked, because it made me explore my feelings on the matter a bit more.In original Dungeons & Dragons, raise dead is a 5th-level cleric spell, the highest level of such spells available prior to the publication of Greyhawk. The earliest a player character can gain access to this spell is 7th level (50,000 experience points). The spell is described thusly:

The Cleric simply points his finger, utters the incantation, and the dead person is raised. This spell works with men, elves, and dwarves only. For each level the Cleric has progressed beyond the 8th, the time limit for resurrection extends another four days. Thus, an 8th level Cleric can raise a body dead up to four days, a 9th level Cleric can raise a body dead up to eight days, and so on. Naturally, if the character's Constitution was weak, the spell will not bring him back to life. In any event raised characters must spend two game weeks time recuperating from the ordeal.

Greyhawk introduces two new spell levels for clerics, 6th and 7th, with the latter including the spell raise dead fully that is functionally identical to its 5th-level counterpart, except that "no rest or recuperation is required thereafter." This spell first becomes available at 17th level, which I suspect effectively put out of easy reach of most player characters.

The Empire of the Petal Throne equivalent is revivify, the highest level "priestly skill" in the game. At level 1, EPT characters begin with 2 to 5 abilities chosen from a chart. How many of these abilities an individual character gets is randomly determined, That said, revivify is available to a priest no sooner than level 8 (120,000) and no later than level 11 (440,000). Bear in mind, too, the XP penalties the game employs to slow progression, starting at level 4. This is significantly later than in OD&D by any metric.

The description of revivify is as follows:

Depending on the character's constitution (Cf. Sec. 413 above), this spell restores one slain human or intelligent nonhuman to life. A newly revived being cannot engage in fighting for a period of one week. This spell must be used within one week of the being's death; otherwise he or she cannot be revived. Usable once a week by persons of eighth level or below; usable once a day by those above eighth level.

It's fascinating to note the mechanical similarities and differences, which are no surprise, given that EPT's rules were heavily inspired by those of OD&D. What I think is most notable, though, is how much more difficult it would be for an Empire of the Petal Throne player character to gain access to revivify, compared to raise dead in Dungeons & Dragons. I suspect this is intentional, as one M.A.R. Barker's early criticisms of D&D was that the game's rules were devoid of any social context, seemingly existing in a societal vacuum. Tékumel is, in part, an answer to that perceived vacuum, grounding its mechanics in a social structure so that there are consequences and stakes to the implications of the rules.

Ultimately, I think my unease with raise dead rests somewhere in this vicinity. It's both too readily available to player characters – 50,000 XP isn't all that much in OD&D, even after the Greyhawk changes – and without any larger context. Mind you, that's a problem with D&D generally, though I understand that many, not without reason, don't see this as a problem per se but rather a kind of design agnosticism. That's fair, I think, but it does little to answer my own concerns, except perhaps to say, "If you don't like it in your campaign, change it."

In the case of the House of Worms campaign, I haven't changed anything with regard to the revivify spell. None of the priest characters in the group is yet high enough level to cast the spell. Likewise, the two instances of resurrection to occur didn't involve the spell but instead near-miraculous events outside the control of the players. Rather, they were orchestrated by me as the referee, because I saw an opportunity to use a character's death(s) to do something interesting in the campaign. That's the crux of it for me: I don't actually object to the idea of raising a character from the dead, even multiple times. What I object to is the reduction of this event to something ordinary, something that can happen at the beck and call of player characters. If a character is to rise from the dead, I want it to be special.

If that makes me a hypocrite or inconsistent, I'll own that. It certainly wouldn't be the first time I've talked out of both sides of my mouth and likely won't be the last.

February 3, 2022

Real-life Clerics: TSR Hobbies Needs You

This notice appeared in issue #40 of Dragon (August 1980). I can only assume that this was part of a public relations campaign in the aftermath of the James Dallas Egbert disappearance the previous August, which first brought Dungeons & Dragons to national attention in the USA.

Search for the Emperor's Treasure

Tom Wham is an underappreciated game designer in my opinion. While several of his designs, like The Awful Green Things from Outer Space, are quite well known and rightly celebrated, his games that appeared in the pages of Dragon magazine are often overlooked (though, admittedly, Snit's Revenge, is an example of a design that appeared first in Dragon). I remember playing several of them with my friends, like King of the Tabletop and Elefant Hunt, and having a great time.

Remembering this recently, I started looking into other designs of Wham's that I might not have encountered. In doing so, I came across Search for the Emperor's Treasure, which appeared in issue #51 of Dragon (July 1981). Since I've yet to play it, I can't comment on the game itself. One aspect of it that stood out even on a cursory examination was its accompanying map, drawn by none other than Darlene. It's absolutely lovely, like the maps of many fantasy boardgames from those days, makes me think it might make for the basis of a good campaign setting.

Enjoy!

Death, Resurrection, and the Fear of Fish

I've mentioned before that one of the longstanding player characters in my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, Aíthfo hiZnáyu, recently died as a result of an instant death critical hit. I've also mentioned that this unexpected turn of events was soon followed by the equally unexpected resurrection of Aíthfo by means unknown to the players (including Aíthfo's own player). However, it's not unknown to me, as the referee. While I had not planned that Aíthfo would die – the dice have their own ideas, after all – I quite quickly came up with a way to make use of his death to develop further my own particular take on M.A.R. Barker's world of Tékumel, as well as to advance the continually unfolding events of the larger campaign.

I've mentioned before that one of the longstanding player characters in my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, Aíthfo hiZnáyu, recently died as a result of an instant death critical hit. I've also mentioned that this unexpected turn of events was soon followed by the equally unexpected resurrection of Aíthfo by means unknown to the players (including Aíthfo's own player). However, it's not unknown to me, as the referee. While I had not planned that Aíthfo would die – the dice have their own ideas, after all – I quite quickly came up with a way to make use of his death to develop further my own particular take on M.A.R. Barker's world of Tékumel, as well as to advance the continually unfolding events of the larger campaign.Strictly speaking, I didn't need to do this and I expect that many diehard old school referees would likely balk at the idea of restoring a player character to life so soon after his demise. More than that, Aíthfo's resurrection required no effort on the part of his comrades, who had decided in the immediate aftermath of his death to seek out some means of reversing it at the next large settlement they encountered. Why rush things? Why not simply wait and see wait happened? Indeed, why not actively thwart the efforts of the other PCs to find a method of raising Aíthfo from the dead? Was I not being "soft" in blunting the cruel whims of fate?

These are all fair questions. I actually have a great deal of sympathy for those who feel that resurrection and similar spells undermine important aspects of gameplay (for RPGs are games and, at least in part, games of chance). In principle, I remain committed to not only the idea but the ideal of random, meaningless player character death, even for PCs of longstanding like Aíthfo. I'm firmly of the opinion that, if you don't want player characters to die in this fashion, why roll dice at all? For success to have any meaning, there must be the real chance of failure, up to and including the death of a player character.

In this particular case, though, there were two factors that pushed me toward bringing back Aíthfo as I did. The first and most pressing was that Aíthfo had died once before and been brought back to life. His original resurrection was a blessing in disguise for the campaign, as it gave me the chance to explore the religion and worldview of the Naqsái people whom the PCs had only just begun to understand. The other players were just as determined as to resurrect Aíthfo from his second death and that didn't sit well with me. Either I'd have to block their attempts at every turn, which felt heavy-handed, or they'd ultimately succeed, which I think would have suggested character death was, at best, a mere obstacle to be overcome rather than a significant event in the campaign.

The second factor is that there were still aspects of Tékumel I wanted to get the chance to explore, specifically the nature of the gods and their involvement in mortal affairs. I began to touch on this during the time of Aíthfo's original resurrection and had been looking for an opportunity to continue to do so. His second death seemed the perfect opportunity and I decided to seize it. Coupled with my unease at allowing Aíthfo to be raised from the dead simply because the rules of Empire of the Petal Throne allow it, I feel like this was a reasonable approach to the problem at hand.

Of course, not everything has gone as expected. Yes, Aíthfo is alive again, but there's something clearly off about him. In last week's session, our 255th, he expressed an aversion to fish. This aversion was born out of the sense that fish can't be trusted: they're everywhere in the sea and they were following him. He, therefore, refused to get on the sea vessel the characters were using to travel to the Isle of Sweet Gentility (aka the Isle of Ghosts), because it would bring him closer to the fish he now feared. Only swift thinking by Znayáshu, who offered Aíthfo a "magical" bone of fish warding – an ordinary cat bone that he had in his divination bag – convinced him to board the ship and continue their journey westward along the coast of the Achgé Peninsula.

Aíthfo's ichthyophobia is a consequence of his resurrection – and a clue as to its nature. No one has yet figured out what it means or what it might presage, but there will be consequences in the weeks to come. Since hitting upon the idea behind all this, I feel much less uncomfortable with bringing Aíthfo back from the dead than I might otherwise have. There's a real benefit to the overall campaign, not just to the player characters. Plus, it makes better sense within the world of the campaign; it has meaning. For me, that's far more important than any other consideration.

February 2, 2022

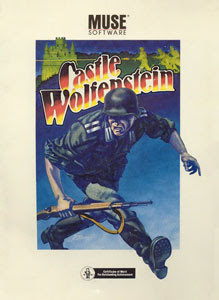

Retrospective: Castle Wolfenstein

As a general rule, I've tried to keep the entries in the Retrospective series focused on roleplaying games, but I've regularly bent that rule over the years. I've often done so when a particular non-RPG product, whether it be a wargame, a boardgame, or even a videogame, played an important role in my own gaming history – and Castle Wolfenstein, like

Telengard

, was a very important game for me.

As a general rule, I've tried to keep the entries in the Retrospective series focused on roleplaying games, but I've regularly bent that rule over the years. I've often done so when a particular non-RPG product, whether it be a wargame, a boardgame, or even a videogame, played an important role in my own gaming history – and Castle Wolfenstein, like

Telengard

, was a very important game for me.Castle Wolfenstein was originally released in 1981 for the Apple II by a company called Muse Software. Muse was headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland, not far from where I grew up, which may explain why I had an inordinate affection for the game. I didn't own a computer of any sort at the time, let alone an Apple II, but a good friend's father owned an Atari 400 and he was very generous in allowing the neighborhood kids to play games on it. An Atari-compatible version of Wolfenstein appeared in 1982 and that was the one I played (once my friend's dad acquired it, of course).

The premise of Castle Wolfenstein was straightforward: you play an Allied spy during World War II who's been captured and consigned to the dungeons beneath the titular castle for interrogation by the SS. Your goal is to locate the secret battle plans you were carrying before your capture and escape the castle. To do that, you first have to find a way out of the dungeon where you're being held. Fortunately for you, another prisoner, who's been hiding in secret, smuggles you a pistol, ammunition, and three grenades before dying. Armed with these, the player must then use his wits to escape the procedurally-generated chambers of the castle.

That may sound like a simple task, but, believe me, it's not. The castle is filled with guards, stormtroopers, and locked doors that impede your progress. To escape, you not only need to marshal your available resources, but also your wits. Though violence is a perfectly acceptable means of dealing with foes, sometimes it's better to avoid them. To this day, I can still hear the distinctive clicking sounds made by a guard marching down a hallway with his back to me. If you timed it just right, you could slip past him and into another area without having to fight him. That was a good option in many cases, because ammunition was limited and combat could be dangerous.

Providing non-violent solutions to some problems was one of the things I really appreciated about Castle Wolfenstein, especially when compared to most other videogames at the time. In addition to outright stealth, you could sometimes find uniforms in the castle that, when worn, would enable you to disguise yourself as a guard and pass unhindered through some areas. Likewise, it was possible under certain conditions to get a guard to surrender to you rather than having to kill him. This wasn't simply a matter of humanitarianism; conserving ammunition was a valuable resource. For times when violence is the only solution, such as when facing stormtroopers, grenades were often the weapon of choice. Grenades were also useful for blasting open doors and walls – and, if you weren't careful, yourself.

My friends and I had a lot of fun with Castle Wolfenstein. The game's premise was compelling and its many features were genuinely innovative for the time. More than that, though, it was one of those rare games that truly rewarded cleverness and patience. This was not an arcade shoot-em-up but an early example of the stealth genre that would develop more fully in years to come. At the time, this was a very novel thing and it inspired us to consider using similar tactics in our roleplaying games. Even now, I think back to the way Castle Wolfenstein provided the player with a variety of viable solutions to many problems. It's a good model for not just videogames but RPG adventures too.

February 1, 2022

You Are Earth's Only Hope!

While the efficacy of advertising for its intended purpose is open to question, I nevertheless find it difficult to deny that many advertisements are exceptionally good at sticking in one's memory, even after decades. A good example of what I'm talking about is this ad for Yaquinto's 1981 game, Attack of the Mutants.

I never saw, let alone owned this game, but I've never forgotten the image below – and there's a good reason for that. The illustration accompanying the advertisement was drawn by John Hagen-Brenner, best known for illustrating the works associated with the Church of the SubGenius (he also illustrated other games from Yaquinto, like Hero). It's a very memorable piece of artwork that amusingly evokes 1950s B-movie "atomic horror." No wonder I can still see it in my mind's eye after all these years!

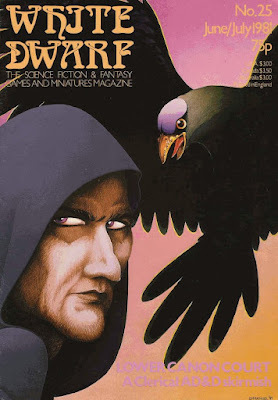

White Dwarf: Issue #25

Issue #25 of White Dwarf (June/July 1981) features a cover by Fiend Folio cover artist, Emmanuel. In addition, Emmanuel provides all of the issue's interior art, except for graphical elements and headers that first appeared in previous issues. Having a single artist handle all the artwork of a single periodical issue is quite unusual in my experience, which is why it's all the more striking in this instance. Mind you, compared to, say, Dragon of the same era, White Dwarf had a lot less artwork per issue. Still, I couldn't help but take note of it. Also worthy of note is that this issue marks the fifth anniversary of White Dwarf's publication.

Issue #25 of White Dwarf (June/July 1981) features a cover by Fiend Folio cover artist, Emmanuel. In addition, Emmanuel provides all of the issue's interior art, except for graphical elements and headers that first appeared in previous issues. Having a single artist handle all the artwork of a single periodical issue is quite unusual in my experience, which is why it's all the more striking in this instance. Mind you, compared to, say, Dragon of the same era, White Dwarf had a lot less artwork per issue. Still, I couldn't help but take note of it. Also worthy of note is that this issue marks the fifth anniversary of White Dwarf's publication.

Part III of Lewis Pulsipher's "An Introduction to Dungeons & Dragons" focuses on playing "the spell-using classes," as he calls them – but not all of them. Druids, for example, are specifically excluded as being very different from magic-users or clerics. Illusionists are not discussed either, but I am assume that's because this article is geared more toward original Dungeons & Dragons rather than AD&D and illusionists do not appear in any OD&D rulebooks or supplements, having debuted in The Strategic Review. In any case, Pulsipher's advice on playing these two classes is fairly straightforward and sensible. He emphasizes their distinct roles and the spells and abilities they possess that best support those roles. There's not much new here to longtime players of D&D and much of what he says has passed into widely accepted conventional wisdom. However, he does make one point worthy of mention, namely that clerics are, in fact, potent warriors in their own right and ought to be played as such rather than as magic-users with a less spectacular selection of spells. To that end, he counsels that "rough 20% of a party" should be clerics, as their hybrid nature makes them very valuable to any dungeon expedition.

Trevor Graver's "The Self-Made Traveller" is a set of optional skill acquisition rules for Traveller. The purpose behind the rules is to eliminate the randomness of Traveller character generation by giving players points to spend on selecting skills of their choice for their characters. I can't say I see much appeal in this, as Traveller's random character generation system is one of its strongest – and most fun – elements, but I have no doubt there are those who disagree. "Open Box" reviews Space Opera (8 out of 10), Plunder and RuneMasters for RuneQuest (5 out 10 and 9 out of 10 respectively), and Double Adventure 2 for Traveller. Of these reviews, I think the one for Space Opera is the most fascinating, as it's written by Andy Slack. Slack praises the game as "complicated" but nevertheless full of "rewarding and entertaining" detail that some might find more enjoyable than other SF RPG offerings.

"The Dungeon Architect" by Roger Musson is one of the more celebrated series of articles from the early days of White Dwarf. Part I, entitled "The Dungeon Interesting" kicks it off with an overview of the concept of dungeons, followed by thoughts on why a dungeon might exist, what manner of beings might exist within its labyrinths, and who or what might dwell nearby on the surface world. In and of themselves, these questions are not particularly interesting and most referees have probably given them some thought before creating their own dungeons. What makes this article valuable, though, is the way that Musson presents each question and then methodically lays out a series of possible answers to each one, along with ideas to spark the reader's creativity. It's an excellent kick-off to a series that will continue in the issues to come.

"Lower Canon Court" by Tony Chamberlain and Paul Skidmore is an odd little mini-game to be used with AD&D. It's intended to represent a clerical court for the trying of those who've gone against the dictates of their alignment and/or religious beliefs, but it's presented as a skirmish complete with a map, two dozen NPCs, and crypts filled with undead beneath the court. At first, I thought this was intended as a kind of trial-by-combat affair, but that doesn't seem to be the case at all. Instead, players are given control of the various NPCs, each of whom has notes about how he views the court and will judge potential defendants. There's a chance the undead might escape the crypts and disrupt the judicial proceedings, but that's an extra feature of the situation rather than its purpose. I suppose this might fun as a one-off scenario.

"Treasure Chest" presents four new miscellaneous magic items and some quick rules on character handedness. The byline of Roger E. Moore once again figures prominently in this section, as it has in several recent issues. "Blowout!" by Andy Slack is a set of expanded rules for vacuum suits in Traveller and is quite well done. I'd recommend making use of it, if your campaign features the regular use of vacc suits and you'd benefit from the added detail. "The Fiend Factory" presents a series of five "themed" monsters, all of which can be found in The Black Manse, the cursed dwelling of a benevolent baron whose son is not so well-intentioned. This is a good structure for presenting new D&D monsters and I think it sets this installment of "The Fiend Factory" apart from most other collections of new monsters.

"The Ship's Library" by Bob McWilliams discusses books, both fiction and non-fiction, that every Traveller referee ought to read to help in setting up a campaign. "What Makes a Good AD&D Character Class" by Lewis Pulsipher concludes the issue with his thoughts on the subject at hand. Most of those thoughts are common sense, such as "don't make the class too powerful," but what is commonsensical now might not have been so in 1981. Consequently, I doubt many reading it today would derive much benefit from it.

Issue #25 is a very good one, filled with numerous interesting articles. These articles also seem to be getting longer, which I appreciate, but this comes at a cost. Since the magazine's page count hasn't increased noticeably, the size of the text is getting smaller. That probably would have been fine when I was a teenager, but nowadays, I find it vexing. Oh, to be young again!

January 31, 2022

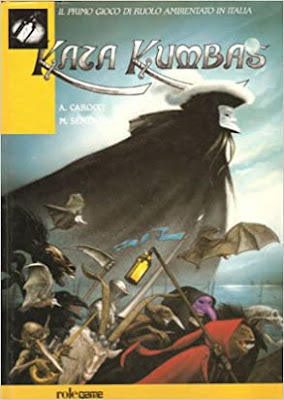

Mago

An illustration of a wizard (mago) from the second edition of the Italian fantasy roleplaying game, Kata Kumbas (1988).

Kata Kumbas

Second edition cover by John HoweBecause I know so little about the early roleplaying game scenes outside the English-speaking world, I appreciate it when readers educate me. Recently, Adamo Degradi shared some information about the 1980 French game, Le Château des Sortilèges, about which I previously knew nothing. I thanked him for this and he then asked me if I'd like to know something about an early Italian RPG, Kata Kumbas. Naturally, I was quite interested, since I'd never heard of the game before, let alone seen it.

Second edition cover by John HoweBecause I know so little about the early roleplaying game scenes outside the English-speaking world, I appreciate it when readers educate me. Recently, Adamo Degradi shared some information about the 1980 French game, Le Château des Sortilèges, about which I previously knew nothing. I thanked him for this and he then asked me if I'd like to know something about an early Italian RPG, Kata Kumbas. Naturally, I was quite interested, since I'd never heard of the game before, let alone seen it. Designed by Agostino Carrocci and Massimo Senzacqua, Kata Kumbas was the second Italian language roleplaying game ever published. It first appeared in 1984 just a few months after I Signori del Caos. Unlike its predecessor, Kata Kumbas featured an original rules system – I Signori del Caos was derivative of AD&D – and, more importantly, a setting based on a fantastical version of Italy (or Laitia). Laitia has many inspirations, from Orlando Furioso to Italo Calvino's Italian Folktales to sword-and-sandal movies. As a result, Kata Kumbas has a comedic and picaresque tone, especially when compared to most English-language games available at the time.

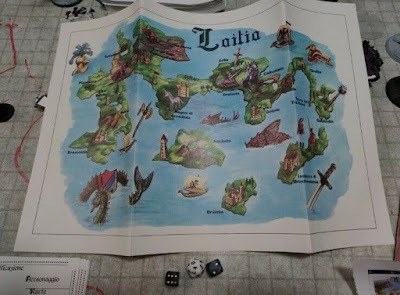

Map of LaitiaThere are several genuinely unique aspects of the game's design, a couple of which I want to highlight. First, the characters are the players themselves, whose minds have been transplanted to another reality. Once there, the players must choose a new persona from among four different kin (Hyperboreans, Roma, the Ancient People, and the New People) and thirteen classes (or castes). Speaking only for myself, I find this premise fascinating, not least because it strongly echoes many early fantasy stories, in which the protagonist is a stranger to the world, having come to it from present-day Earth. I'm hard pressed to think of any English-language RPGs where this is the case, so it's all the more remarkable that Kata Kumbas embraces it.

Map of LaitiaThere are several genuinely unique aspects of the game's design, a couple of which I want to highlight. First, the characters are the players themselves, whose minds have been transplanted to another reality. Once there, the players must choose a new persona from among four different kin (Hyperboreans, Roma, the Ancient People, and the New People) and thirteen classes (or castes). Speaking only for myself, I find this premise fascinating, not least because it strongly echoes many early fantasy stories, in which the protagonist is a stranger to the world, having come to it from present-day Earth. I'm hard pressed to think of any English-language RPGs where this is the case, so it's all the more remarkable that Kata Kumbas embraces it.

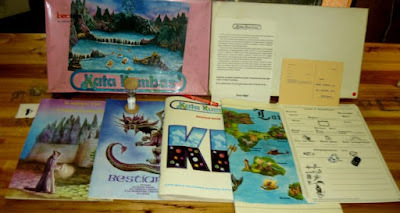

Contents of the first edition boxed setThe second unique aspect to the game I want to draw attention to is the inclusion of a five-minute hourglass, in addition to dice. The hourglass was apparently used to keep track of how long a spirit remained bound to a summoner. Once again, this is something I can't recall ever seeing incorporated into an English-language RPG.

Contents of the first edition boxed setThe second unique aspect to the game I want to draw attention to is the inclusion of a five-minute hourglass, in addition to dice. The hourglass was apparently used to keep track of how long a spirit remained bound to a summoner. Once again, this is something I can't recall ever seeing incorporated into an English-language RPG. There is, I am sure, a great deal more that could be said about Kata Kumbas, but I will leave that to readers who have actually seen and played the game themselves. Based solely on the little I've gleaned about it, I think it's something I'd probably have enjoyed. It's also a reminder of how delightfully different the RPG scenes of other countries can be from those with which I am already familiar.

January 30, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Flower-Women

Clark Ashton Smith clearly had a fondness for the character of Maal Dweb. After the completion of "The Maze of the Enchanter," he penned a second story set on the alien world of Xiccarph, entitled "The Flower-Women." Like its predecessor, the story met with resistance from the editor of Weird Tales, Farnsworth Wright, who called it "well done" but deemed it "a fairy story rather than a weird tale proper." Lovecraft, who was ardent admirer of many of Smith's efforts, didn't think much of this particular yarn either, calling it "below par" in a contemporary letter to R.H. Barlow.

Clark Ashton Smith clearly had a fondness for the character of Maal Dweb. After the completion of "The Maze of the Enchanter," he penned a second story set on the alien world of Xiccarph, entitled "The Flower-Women." Like its predecessor, the story met with resistance from the editor of Weird Tales, Farnsworth Wright, who called it "well done" but deemed it "a fairy story rather than a weird tale proper." Lovecraft, who was ardent admirer of many of Smith's efforts, didn't think much of this particular yarn either, calling it "below par" in a contemporary letter to R.H. Barlow. Wright eventually changed his opinion and "The Flower-Women" was published in the May 1935 issue of Weird Tales. The story opens with Maal Dweb experiencing intolerable ennui, an emotional state he resolves to alleviate.

"There is but one remedy for this boredom of mine," he went on — "the abnegation, at least for a while, of that all too certain power from which it springs. Therefore, I, Maal Dweb, the ruler of six worlds and all their moons, shall go forth alone, unheralded, and without other equipment than that which any fledgling sorcerer might possess. In this way, perhaps I shall recover the lost charm of incertitude, the foregone enchantment of peril. Adventures that I have not foreseen will be mine, and the future will wear the alluring veil of the mysterious. It remains, however, to select the field of my adventurings."I doubt I'm alone in finding this set-up quite compelling – and reminiscent of the kind of thing a high-level D&D character might do after finding his most recent adventures insufficiently challenging. Maal Dweb then consults his magical orreries and resolves to pay a visit to the farthest planet of the star system, Votalp.

Votalp, a large and moonless world, revolved imperceptibly as he studied it. For one hemisphere, he saw, the yellow sun was at that time in total eclipse behind the sun of carmine; but in spite of this, and its greater distance from the solar triad. Votalp was lit with sufficient clearness. It was mottled with strange hues like a great cloudy opal; and the mottlings were microscopic oceans, isles. mountains, jungles, and deserts. Fantastic sceneries leapt into momentary salience, taking on the definitude and perspective of actual landscapes, and then faded back amid the iridescent blur. Glimpses of teeming, multifarious life, incredible tableaux, monstrous happenings, were beheld by Maal Dweb as he looked down like some celestial spy.

By means of "a deep and hueless cloud," which affords Maal Dweb "access to multiple dimensions and deeply folded realms of space conterminate with far worlds," the mighty sorcerer makes his way to Votalp. There, he makes his way into a valley where heard "an eerie, plaintive singing, like the voices of sirens who bewail some irredeemable misfortune."

The singing came from a sisterhood of unusual creatures, half woman and half flower, that grew on the valley bottom beside a sleepy stream of purple water. There were several scores of these lovely and charming monsters, whose feminine bodies of pink and pearl reclined amid the vermilion velvet couches of billowing petals to which they were attached. These petals were borne on mattress-like leaves and heavy, short, well-rooted stems. The flowers were disposed in irregular circles, clustering thickly toward the center, and with open intervals in the outer rows.

Maal Dweb approached the flower-women with a certain caution; for he knew that they were vampires. Their arms ended in long tendrils, pale as ivory, swifter and more supple than the coils of darting serpents, with which they were wont to secure the unwary victims drawn by their singing. Of course, knowing in his wisdom the inexorable laws of nature, he felt no disapproval of such vampirism; but, on the other hand, he did not care to be its object.

I find it interesting that, while Maal Dweb is the protagonist of this tale, Smith does not shy away from the fact that he is an evil man. His ready acceptance of vampirism contrasts with the reactions of more traditional pulp fantasy protagonists, who would likely view the flower-women as frightful creatures. Instead, Maal Dweb finds them "lovely and charming." There isn't a hint of fear or condemnation, only the recognition that he must be wary of them.

The sorcerer nevertheless forgets himself and falls prey to their "wild and sweet and voluptuous singing, like that of the Lorelei." He finds that the melody "fire[s] his blood with a strange intoxication" and he is soon drawn to the flower-women. Once in their presence, he regains something of his mental faculties and uses his "power of divination" to learn more about them. He then discovers that five of their kind had been uprooted over the course of five successive mornings by "certain reptilian beings, colossal in size and winged like pterodactyls, who came down from their new-built citadel." Known as the Ispazars, these reptile-men were themselves magicians of no mean talent, as well as "masters of an abhuman science."

Now, through an errant whim, in his search for adventure, he had decided to pit himself against the Ispazars, employing no other weapons of sorcery than his own wit and will, his remembered learning, his clairvoyance, and the two simple amulets that he wore on his person.

"Be comforted," he said to the flower-women, "for verily I shall deal with these miscreants in a fitting manner."

With that, "The Flower-Women" suddenly becomes a different story, one in which the villainous Maal Dweb, the tyrant of six worlds, becomes more than the protagonist of the story. To the flower-women, at least, he becomes a hero, as the remainder of the story chronicles his efforts on their behalf, avenging the destruction of their kind by the Ispazars. It's quite a startling thing to read and I found myself wondering whether or not Smith had intended this shift, however subtle, to point toward a change in Maal Dweb's character. Even if that wasn't his intention, he does seem to signal an intention to tell more stories of Maal Dweb's adventures among the worlds he rules.

Unfortunately, it was not to be. "The Flower-Women" is the second and last story of Xiccarph. No further stories of the magician ever appeared and, so far as I know, there's no evidence any more were planned. It's a pity, as Maal Dweb is a genuinely interesting character, and I can't help but wonder what more might have awaited him. In just two stories, he went from antagonist to protagonist to something approximating a hero. That's the kind of transformation that few writers could pull off, but Clark Ashton Smith made a good start of it here.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers