James Maliszewski's Blog, page 133

August 10, 2021

White Dwarf: Issue #4

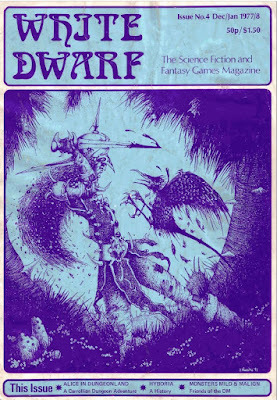

Issue #4 of White Dwarf (December 1977/January 1978) features a cover by the incomparable John Blanche, who would later go on to become of the signature artists of Warhammer, in both its miniatures battles and RPG versions. Its opening editorial, by Ian Livingstone, bemoans the state of the British gaming industry, pointing out that, as of the time of publication, there was only one UK wargames company and none devoted to RPGs. I find this interesting, in light of the fact that Games Workshop would eventually become one of the juggernauts of the hobby and, while it no longer publishes its own RPGs, GW nevertheless remains a force to be reckoned with even in the 21st century.

Issue #4 of White Dwarf (December 1977/January 1978) features a cover by the incomparable John Blanche, who would later go on to become of the signature artists of Warhammer, in both its miniatures battles and RPG versions. Its opening editorial, by Ian Livingstone, bemoans the state of the British gaming industry, pointing out that, as of the time of publication, there was only one UK wargames company and none devoted to RPGs. I find this interesting, in light of the fact that Games Workshop would eventually become one of the juggernauts of the hobby and, while it no longer publishes its own RPGs, GW nevertheless remains a force to be reckoned with even in the 21st century."Alice in Dungeonland" by Don Turnbull is truly fascinating article in which the author describes eleven "features" of the "Alice level" of "the Greenlands Dungeon," which I can only assume was the "tent pole dungeon" of his home campaign. Equally fascinating is that, unlike Gary Gygax's Dungeonland, which directly translates people and places from Lewis Carroll's famous book into AD&D, the features of the "Alice level" are (mostly) inspired by things described in the Alice stories rather than directly imported.

Lewis Pulsipher continues his series on "D&D Campaigns," this time discussing "some practical aspects of constructing dungeons and setting up a campaign." He notes that, more so than other articles in this series, it's intended for neophytes and "may not be of much use to veteran referees." Pulsipher is indeed correct in this assessment, as his advice, while completely sound, includes the sorts of things that most of us have reader dozens of times in many places. In fairness, some of this advice might have been genuinely new in 1977 (and, of course, it's always new to those who've never before served as a referee).

The article entitled "Hyboria" is written by Tony Bath and provides an overview of his famed Hyboria miniatures wargames campaign. Though short, it's a terrific article for anyone interested in the process that led Bath to create his campaign setting. In some ways, it's better than Pulsipher's preceding article, even though it's far less detailed. I was also struck by his conclusions.

What are the lessons of Hyboria? Well, firstly, what you get out of a game is in relation to the amount of effort you put into it. Secondly, a well constructed fantasy soon takes on its own life, and from that point needs only minimal guidance. Finally, if you want to test the limits of your imagination and still keep the whole thing within a logical framework, there is no better medium than creating a fantasy world. Besides, it's fun!

I doubt anyone could disagree with anything he says here.

"Open Box" reviews Nomad Gods by Chaosium, Star Empires and Dungeon! by TSR, and Melee from Metagaming. Of the four games reviewed, Melee – the first part of The Fantasy Trip – is the one that receives the harshest criticism, mostly on the grounds that "there are no really original ideas in this game." The reviewer, Martin Easterbrook, seems to have felt that "anyone who has already adapted rules" would have no need of Melee, which is probably a fair point. It's a reminder, I suppose, that, in 1977, kit bashing of one degree or another was widely assumed; playing a game straight out of the box with no modifications was perhaps unusual, let alone the expectation that would could do so, hence reviews like this.

Don Turnbull returns with "Monsters Mild and Malign," where he talks about the process of creating new and unusual monsters with which to challenge players. He offers three of his own, in addition to citing examples he likes from other sources. More interesting to me was his principle of MERIT – "make empty rooms interesting too." According to this principle, the referee should set up

an array of magical effects, interesting traps, intriguing though valueless pieces of furniture, curious artifacts, new magical items or whatever strikes your fancy and which will present something of a challenge to intruders.

The question of empty rooms and the "best" way to present them remains a much debated matter. I confess that I continue to struggle with it myself, having come to no firm conclusions about it. It's a topic that's been on mind lately as I dive into the design of the main Vaults beneath the city of Inba-Iro in my upcoming sha-Arthan setting. I'll likely have more to say on this matter once I've begun play.

Brian Asbury presents a Barbarian character class that bears many similarities to the one that Gary Gygax would one day include in Unearthed Arcana, as well as many differences. This version of the barbarian is much less physically robust, having only six-sided hit dice (though it does appear to have been written for OD&D rather than AD&D), but, in exchange, it gets a variety of wilderness-related abilities, as well as fearlessness, ferocity, and the ability to catch missiles. I'm not sure I'd ever use the class myself, but I can't deny that it has a distinct flavor that differentiates it from fighting men or rangers. Meanwhile, Andy Holt's "The Loremaster of Avallon" presents an absurdly complex system for dealing with parried and unparried blows that I simply glossed over. I appreciate the value of detail in many areas, but combat is not one that matters much time, hence my preference for keeping it simple. Consequently, articles like this do nothing for me.

"Competitive D&D" by Fred Hemmings continues with the details of several more rooms from his competition dungeon, this time from its fifth level. Several of them are cleverly done and I was glad Hemmings shared them. However, I feel as if they'd have made more sense if they'd been given more overall context, even if it had made the article longer. Still, I remain fascinated by the kinds of dungeons referees designed in the early days of the hobby; articles like this give me a little more insight into the matter.

All in all, issue #4 was a good read. I particularly enjoyed the content that was clearly derived from play and spoke to the though referees put into the design of their dungeons and campaign settings. I hope that we'll continue to see this sort of thing in future issues, perhaps in lengthier and more detailed forms.

August 9, 2021

The Dungeons of Kollchap

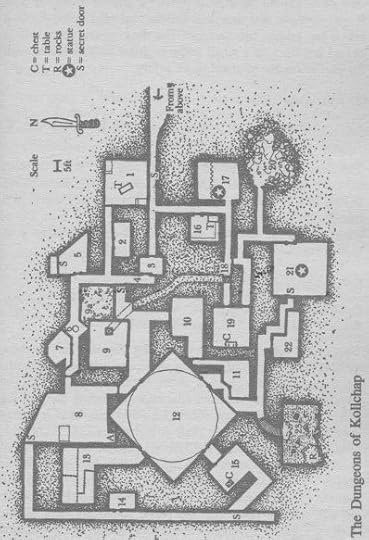

Quite some time ago, a reader very kindly sent me a couple of books to read, one of which was Butterfield, Parker, and Honigmann's What is Dungeons & Dragons? After I'd read it all those years ago, I'd intended to write several posts about its contents, but never did so, unfortunately. Recently, while doing some cleaning, I came across the book again, which includes the sample dungeon map below.

The Dungeon of Kollchap, as it is called, is described in some detail in the book. Each room gets a paragraph or two, along with game stats (which appear based on the Tom Moldvay D&D Basic Rules). There's even a new monster type, "an animated humanoid, made of red-coloured stone," called a Rockman.

The Dungeon of Kollchap, as it is called, is described in some detail in the book. Each room gets a paragraph or two, along with game stats (which appear based on the Tom Moldvay D&D Basic Rules). There's even a new monster type, "an animated humanoid, made of red-coloured stone," called a Rockman. All in all, the Dungeon of Kollchap is nothing special but then it's not really supposed to be. Its purpose is to illustrate the principles of dungeon design, the subject of the chapter of the book in which it appears. In this respect, it's more than adequate, with a few charming features, like a female halfling NPC named Rosa Dobbit, and a rhyming statue that answers questions put to it so long as they contain twelve or fewer words. As I said, nothing world shattering, but I have a fondness for "beginner" dungeons, especially those intended for illustrative purposes like this one.

Chenot!

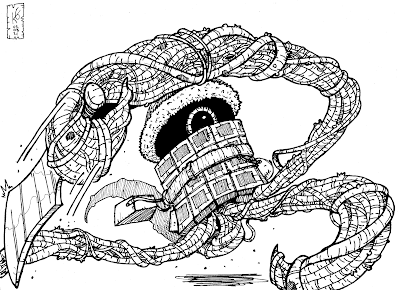

The other day I received what I think is the very first person of fan art for The Vaults of sha-Arthan – an illustration of the Chenot nonhuman species by Kelvin Green.

I absolutely love this piece and the way that Kelvin used the original illustration by Zhu Bajiee and ran with it in a direction all his own.

I absolutely love this piece and the way that Kelvin used the original illustration by Zhu Bajiee and ran with it in a direction all his own. Work on the True World – the setting of Vaults – has kept me busy lately, which is partially responsible for the decreased pace of my posts in the last few weeks. I've put together nearly 30 pages of a rules-focused "Player's Guide" for use by those participating in the campaign once it kicks off. I've still got to finish the magic section and then that's more or less done for the time being, after which I'll begin serious work on presenting an overview of the setting for players.

The process of creating a new fantasy setting has been a great deal of fun. I'm taking particular pleasure in re-imagining and reframing the core elements of D&D – classes, races, spells, etc. – to establish something that's both familiar and alien at the same time. The real test of whether I succeed is how the players in the campaign react to it all, but, thus far, I'm quite happy with the results.

Onward!

August 8, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Testament of Athammaus

Clark Ashton Smith is perhaps my favorite pulp fantasy author, which is why his stories appear so often as entries in this series. Nevertheless, I am frequently torn over which of his works to feature. In part, that's because Smith was so varied and prolific, producing tales in multiple genres, some of which can be grouped into cycles of related stories. Of these cycles, I have a personal preference for those set in the far future of Earth's last continent, Zonthique, or in the forgotten medieval French province of Averoigne and, left to my own devices, I look to those two over others that are equally worthy, such as those taking place in Hyperborea.

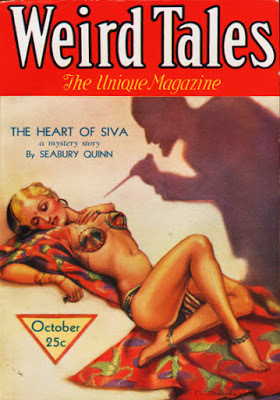

Clark Ashton Smith is perhaps my favorite pulp fantasy author, which is why his stories appear so often as entries in this series. Nevertheless, I am frequently torn over which of his works to feature. In part, that's because Smith was so varied and prolific, producing tales in multiple genres, some of which can be grouped into cycles of related stories. Of these cycles, I have a personal preference for those set in the far future of Earth's last continent, Zonthique, or in the forgotten medieval French province of Averoigne and, left to my own devices, I look to those two over others that are equally worthy, such as those taking place in Hyperborea.Hyperborea is a prehistoric continent that existed before the coming of the Ice Age. At its height, Hyperborea was a warm, even tropical, place that boasted populous cities and a sophisticated culture. Educated Hyperboreans had a decidedly scientific cast of mind and dismissed magic and the supernatural as the superstition of the common folk. Of course, such a dismissal was ill-founded. Many of Smith's tales of Hyperborea involve supposedly "rational" people encountering something that can't easily be explained by recourse to reason and they pay a price for such narrowness of vision.Such is the case with "The Testament of Athammaus," first published in the October 1932 issue of Weird Tales. As its title suggests, the story is a first-person account, written in old age, by a man named Athammaus. Athammaus was once chief headsman of the capital city of Commoriom before its "universal desertion" as a result of "curious and lamentable happenings" in which he "played a signal part." Despite his occupation as a royal executioner, Athammaus is no mere brute. Instead, throughout the narrative, he reveals himself to be a clever, thoughtful man – which is why he struggles to give a proper account of the final days of Commoriom.

Athammaus begins by boasting of his days as a headsman.

there was no braver and more stalwart headsman than I in the whole of Hyperborea; and my name was a red menace, a loudly spoken warning to the evil-doers of the forest and the town, and the savage robbers of uncouth outland tribes. Wearing the blood-bright purple of my office, I stood each morning in the public square where all might attend and behold, and performed for the edification of all men my allotted task. And each day the tough, golden-ruddy copper of the huge crescent blade was darkened not once but many times with a rich and wine-like sanguine. And because of my never-faltering arm, my infallible eye, and the clean blow which there was never any necessity to repeat, I was much honored by the King Loquamethros and by the populace of Commoriom.He then speaks of an outlaw with the delightfully Smithian name of Knygathin Zhaum, who "belonged to an obscure and highly unpleasant people called the Voormis, who dwelt in the black Eiglophian Mountains." The Voormis, we learn,

inhabited according to their tribal custom the caves of ferine animals less savage than themselves, which they had slain or otherwise dispossessed. They were generally looked upon as more beast-like than human, because of their excessive hairiness and the vile, ungodly rites and usages to which they were addicted.

Under Zhaum's leadership, the Voormis had begun to terrorize the people living near the Eiglophian Mountains and engaged in both "iniquitous rapine" and anthropophagy, among even worse atrocities. Athammaus comments that Knygathin Zhaum was an unusual kind of Voormis in that, unlike his fellows, he was completely hairless and covered in "great spots of black and yellow." Worse still, he "exceed[ed] all others in his cruelty and cunning."

Eventually, Zhaum is captured, tried – the folk of Commoriom are civilized, after all – and sentenced to death. It's in this capacity that he and the narrator, Athammaus, cross paths. When the Voormis bandit is brought before the executioner, he "surpassed [his] most sinister and disagreeable anticipations."

He was naked to the waist, and wore the fulvous hide of some long-haired animal which hung in filthy tatters to his knees. Such details, however, contributed little to those elements in his appearance which revolted and even shocked me. His limbs, his body, his lineaments were outwardly formed like those of aboriginal man; and one might even have allowed for his utter hairlessness, in which there was a remote and blasphemously caricatural suggestion of the shaven priest; and even the broad, formless mottling of his skin, like that of a huge boa, might somehow have been glossed over as a rather extravagant peculiarity of pigmentation. It was something else, it was the unctuous, verminous ease, the undulant litheness and fluidity of his every movement, seeming to hint at an inner structure and vertebration that were less than human—or, one might almost have said, a sub-ophidian lack of all bony frame-work—which made me view the captive, and also my incumbent task, with an unparallelable distaste. He seemed to slither rather than walk; and the very fashion of his jointure, the placing of knees, hips, elbows and shoulders, appeared arbitrary and factitious. One felt that the outward semblance of humanity was a mere concession to anatomical convention; and that his corporeal formation might easily have assumed—and might still assume at any instant—the unheard-of outlines and concept-defying dimensions that prevail in trans-galactic worlds. Indeed, I could now believe the outrageous tales concerning his ancestry. And with equal horror and curiosity I wondered what the stroke of justice would reveal, and what noisome, mephitic ichor would befoul the impartial sword in lieu of honest blood.

Forgive me for including this entire passage, but I how could I not do so? In any case, Athammaus later proceeds with his assigned task of severing Zhaum's head from his shoulders.

Necks differ in the sensations which they afford to one's hand beneath the penetrating blade. In this case, I can only say that the sensation was not such as I have grown to associate with the cleaving of any known animal substance. But I saw with relief that the blow had been successful: the head of Knygathin Zhaum lay cleanly severed on the porous block, and his body sprawled on the pavement without even a single quiver of departing animation. As I had expected, there was no blood—only a black, tarry, fetid exudation, far from copious, which ceased in a few minutes and vanished utterly from my sword and from the eighon-wood. Also, the inner anatomy which the blade had revealed was devoid of all legitimate vertebration. But to all appearance Knygathin Zhaum had yielded up his obscene life; and the sentence of King Loquamethros and the eight judges of Commoriom had been fulfilled with a legal precision.

With that, the threat of Knygathin Zhaum is ended – or so it appears, for Athammaus learns a few days later the Voormis bandit had "reappeared and had signalized the unholy miracle of his return by the commission of a most appalling act on the main avenue before the very eyes of early passers!" Caught again and charged with an act of cannibalism, Zhaum is once again tried and sentenced, under "a special statute, calling for re-judgement and allowing re-execution, of such malefactors as might thus-wise return from their lawful graves." As I said above, the folk of Commoriom are civilized! Zhaum is once again brought before Athammaus and beheaded. Surely, this must be the end of him, yes?

"The Testament of Athammaus" is an engaging tale, told with the usual mixture of cynicism and humor that one expects of Clark Ashton Smith. If I had a complaint, it would be that the story drags on a little longer than needed to achieve its ultimate conclusion, but the journey along the way, filled with poetic archaisms, horrific turns, and mordant observations, is so enjoyable that I cannot complain too loudly. This is a terrific short story and deserves wider recognition.

August 6, 2021

Random Roll: PHB, p. 8

Beginning on page 7 of the AD&D Players Handbook, there's a lengthy section entitled simply "The Game," in which Gary Gygax lays out something approximating his understanding of what Advanced Dungeons & Dragons is and how it's meant to be played. It's actually a very good section, devoid of most of the bluster and bombast that unfortunately accompanied many of Gygax's other forays into this topic. I could easily devote many posts to this section (and might well do so in the future), but, for the moment, I wish to focus on a single paragraph toward the end of this section, in which Gygax talks about the role of the referee in using the AD&D rules to create and maintain a campaign.

This game is unlike chess in that the rules are not cut and dried. In many places, they are guidelines and suggested methods only. This is part of the attraction of ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, and it is integral to the game.

Chess is a frequently used reference point in Gygax's discussion of the rules of AD&D, most infamously in his November 1982 essay, "Poker, Chess, and the AD&D System." Here, chess represents a game with clear, objective, and unchanging – perhaps even unchangeable – set of rules, in contrast to AD&D whose rules include many "guidelines and suggested methods only." I find this interesting, because, it initially seems as if the general tenor of what Gygax is saying comports with that of OD&D, but, as we shall see, there are significant differences.

Rules not understood should have appropriate questions directed to the publisher;

So much for "why have us do any more of your imagining for you?" seen in the afterword of Volume 3 of OD&D. It's quite a sea-change in approach.

disputes with the Dungeon Master are another matter entirely. THE REFEREE IS THE FINAL ARBITER OF ALL AFFAIRS OF HIS OR HER CAMPAIGN. Participants have no recourse to the publisher, but they do have ultimate recourse – since the most effective protest is withdrawal from the offending campaign.

That said, I can't help but agree with Gygax here, even if I wouldn't have deployed all capitals in stating it. His advice about dealing with bad referees is practical and effective. I have seen it used several times over the course of my years in the hobby (never against me, of course!). I sometimes think that, had this advice been followed more readily, fewer gamers would today have so many stories of tyrannical referees.

Each campaign is a specially tailored affair. While it is drawn by the referee upon the outlines of the three books which comprise ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, the players add the color and details, so the campaign must ultimately please all participants. It is their unique world.

I like this, though I am fairly certain that Gygax intended a greater degree of uniformity between campaigns than his reference to "specially tailored" might suggest. Nevertheless, his statement that "the campaign must ultimately please all participants" is important. I doubt he meant that it's the duty of the referee to assume that everything always goes the preferred way of the players (and their characters). Rather, he seems to mean that everyone involved, players and referee alike, should have a stake in the campaign and its continuance. That is eminently good advice and true, at least in my own experience.

You, the reader, as a member of the campaign community, do not belong if the game seems wrong in any major aspect. Withdraw and begin your own campaign by creating a milieu which suits you and the group which you must form to enjoy the creation. (And perhaps you will find that preparation of your own milieu creates a bit more sympathy for the efforts of the offending referee …)

I like this as well. Truly, I think more players should try their hands at refereeing, not merely for the reasons Gygax includes in parenthesis but also because I sometimes feel as if many players expect campaigns to cater to their own preferences. Over the years, I've played in several campaigns that, for various reasons, weren't to my taste. In every instance, I ultimately bowed out of the campaign rather than attempting to sway the referee to change those aspects of it that I didn't like. That strikes me as both polite and, dare I say it, adult. If you don't like something, don't partake of it; make your own thing that you do like and have fun with it. Life is too short to bother with games (of all things) that you don't enjoy and whining to get your own way does you no credit.

August 5, 2021

Retrospective: The Free City of Krakow

As a child of the 1970s and '80s, the idea that there might one day be a thermonuclear war between the nations of NATO and the Warsaw Pact was easy to believe. Consequently, I had an immense fascination with post-apocalyptic stories and speculations. In the roleplaying realm, my earliest experiences were with TSR's Gamma World, which I adored (and still do). However, I think there's little question that Gamma World doesn't present a "realistic" version of the End, or at least not one that bears much resemblance to the likely outcome of the simmering Cold War tensions that formed the background of my early life.

As a child of the 1970s and '80s, the idea that there might one day be a thermonuclear war between the nations of NATO and the Warsaw Pact was easy to believe. Consequently, I had an immense fascination with post-apocalyptic stories and speculations. In the roleplaying realm, my earliest experiences were with TSR's Gamma World, which I adored (and still do). However, I think there's little question that Gamma World doesn't present a "realistic" version of the End, or at least not one that bears much resemblance to the likely outcome of the simmering Cold War tensions that formed the background of my early life.That's why, when GDW released Twilight: 2000 in 1984, I didn't need to be convinced to pick up a copy. I was already a fan of GDW, but this game seemed to play to the company's strengths. Founded by wargamers, GDW seemed to me to evince the kind of hard-nosed, practical mindset I associated, rightly or wrongly, with military types. If I'd trust any gaming company to make a solid, grounded RPG about life after the Third World War, it was GDW.

And, for the most part, my trust was well-founded. Twilight: 2000 was far from perfect – many of its rules were more cumbersome than they needed to be – but its presentation of a post-apocalyptic early 21st century was a compelling and, dare I say, believable one, given the parameters established in the game's setting. In addition, GDW thoroughly supported Twilight: 2000 with a wide array of supplementary modules, starting with The Free City of Krakow in 1985. This 44-page book was written by William H. Keith, one of the famed Keith Brothers, who had contributed so much excellent material to GDW's Traveller.

The Free City of Krakow is a very interesting book. Though it does include outlines for multiple adventures, including one very significant one, the bulk of the book is gazetteer of the titular city, its inhabitants, and factions. According to the module's history section, Krakow declared itself a free city in late 1999, after its garrison, the Polish 8th Motorized Rifle Division, supported this declaration and its commander accepted the position of Police Prefect. Now, Krakow operates as a kind of "Casablanca of Eastern Europe," free from the control of the shattered remnants of the Warsaw Pact forces in the area, as well as the NATO stragglers that still survive. It's a pretty interesting set-up for a home base out of which player characters can operate, made all the more interesting by the presence of multiple plots, both large and small, in which they can participate.

The city of Krakow itself is described in detail, along with maps and information on each of the cities districts. Special attention is paid to the economics and infrastructure of the city, since these are the key to Krakow's continued survival. Equally important are the major NPCs who live here, starting with the head of the city council, known as the Dowodca (Leader) – a charismatic and self-aggrandizing fellow who views himself as a Man of Destiny. Pitted against him is the Police Prefect, a former major general in the Polish Army, who feels he would better run the city. Krakow also holds operatives of the KGB, CIA, and DIA, the Israeli Shabak, and other smaller groups, like crime syndicates. It's a cauldron of intrigue and duplicity – and the perfect environment for adventure.Speaking of which, The Free City of Krakow provides plenty of adventure outlines for the referee to use, either directly or as seeds for creating his own. One of them is potentially quite significant, as it involves an invention that might enable microcomputers whose chips were destroyed by the EMPs of nuclear strikes and counterstrikes to function again. Needless to say, if true, this invention is something various parties would kill – or at least pay huge sums – for and it represents a major Maguffin with the potential to tip the balance of power in the post-war world.

Re-reading The Free City of Krakow, what strikes me is how much emphasis GDW places on rebuilding civilization in the aftermath of World War III. Despite its reputation in some circles, Twilight: 2000 was not a game of ruthless murderhobo-ism. Yes, it could be played that way, but the supplementary material generally presented situations where the player characters could improve the lives of those they encountered. This is true of The Free City of Krakow too, which includes lots of detail on smaller settlements that exist in the shadow of the Free City and its bloodthirsty politics. Adventures and campaigns set in this region will inevitably present many opportunities for characters to use their skills to help pick up the pieces of the fallen world. It's precisely for this reason that I so like the module and the others that GDW published over the course of Twilight: 2000's run and why I look forward to one day playing the game again.

August 3, 2021

White Dwarf: Issue #3

Issue #3 of White Dwarf is dated October/November 1977 and features cover art by Alan Hunter, who did a number of illustrations in the Fiend Folio. Its first article is entitled "Solo Dungeon Mapping" and is credited to Roger Moores – please note the terminal "s." I assume, though do not know for certain, that this is a typographical error and that the author's name is, in fact, Roger Moore, better known as Roger E. Moore, who would later go on to become editor of TSR's Dragon. Moore's byline appeared extensively in the pages of gaming periodicals starting in the late 1970s, so it seems very likely that this is the same person, but I could be mistaken.

Issue #3 of White Dwarf is dated October/November 1977 and features cover art by Alan Hunter, who did a number of illustrations in the Fiend Folio. Its first article is entitled "Solo Dungeon Mapping" and is credited to Roger Moores – please note the terminal "s." I assume, though do not know for certain, that this is a typographical error and that the author's name is, in fact, Roger Moore, better known as Roger E. Moore, who would later go on to become editor of TSR's Dragon. Moore's byline appeared extensively in the pages of gaming periodicals starting in the late 1970s, so it seems very likely that this is the same person, but I could be mistaken.In any case, "Solo Dungeon Mapping" is an unusual article. First, though intended for use with Dungeons & Dragons, it makes reference to Empire of the Petal Throne as another game for which it could be useful. Second, the very loose system that Moore presents seems intended to create dungeons with few rooms per level but lots of long corridors and passages up and down between levels. Now, there's nothing wrong with this approach, of course, but it's quite different from the much more cramped style I tend to associate with dungeons.

Fred Hemmings offers another installment of his "Competitive D&D," This time around Hemmings presents more details on the chambers of his competition dungeon, Pandora's Maze, which I welcome, given what he implied about it in his previous two articles. The intention here is to provide examples of the mix of encounters, tricks, and traps he uses in scenarios of this style. Likewise, Don Turnbull continues to plug away at his "The Monstermark System," with a third entry. As before, I found the article long and tedious, with an emphasis on mechanical and mathematical minutiae of little use to me. It's odd because, for years, I had heard people speak so glowingly of the Monstermark and assumed it was easy to use – apparently not!

"Open Box" tackles a large number of Judges Guild D&D products: Ready Ref Sheets, The Judge's Shield, TAC Cards, Tegel Manor, City State of the Invincible Overlord, Character Chronicle Cards, and The First First Fantasy Campaign. By and large, these were all well received by the reviewer, Don Turnbull. For myself, I was struck by how much Judges Guild had already released by this relatively early date. Also reviewed was FGU's Citadel, Fourth Dimension (its original, pre-TSR version), and TSR's Battle of the Five Armies.

Lewis Pulsipher continues his "D&D Campaigns" series, with a lengthy discussion of his philosophy of refereeing. Early on, Pulsipher describes his vision of the referee as a "friendly computer discretion," who interferes in the course of play as little as possible, because "the referee is neither infallible nor completely impartial." It's an interesting perspective and one with which I am largely in agreement. He then elaborates on just what he means by this, offering many examples of how this philosophy operates in practice. I know that Pulsipher is often regarded as smug and stuffy in his approach to gaming, but I found this article engaging and look forward to future installments.

"Colouring Conan's Thews" by Eddie Jones is an overview of miniatures painting – another reminder of this hobby's roots. "The Loremaster of Avallon" by Andy Holt presents more D&D house rules, most notably his card-based combat system, whose use eluded me somewhat. I shall have to re-read it several more times to get a better sense of how the system, which uses 100 cards, each bearing a symbol on it, actually works. John Rothwell's "The Assassin" is a variant of the class presented in Blackmoor, while Ian Waugh's "New Magic Rooms" presents two chambers for placement in a dungeon whose interiors operate according to unusual rules.

I have to admit that I was less impressed with this issue than I was with the previous one. Aside from Lewis Pulsipher's article, there was little that stood out to me as being either original or useful to me. That's the nature of periodicals, of course, but I had hoped that White Dwarf, compared to Different Worlds, would hit the ground running. I guess it's still too early to pass judgment on that score.

August 2, 2021

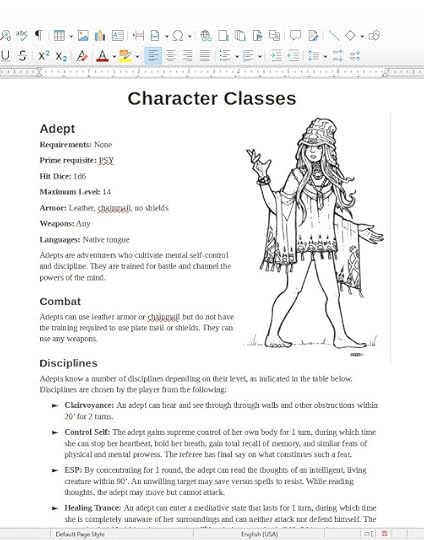

The Vaults of sha-Arthan: Character Classes

I spent a good portion of the past weekend working on the character classes of my The Vaults of sha-Arthan science fantasy setting. I'm happy to say I'm nearly finished this document, though the real work will come once I start refereeing the campaign. I'd originally hoped to be doing that this month, but it'll likely have to wait till September, owing to various real life distractions. As I probably mentioned before, the current plan is to run two concurrent campaigns, one through Discord and another through a play-by-post site. My hope is that this will put development of the setting into overdrive as well as put the rules through their paces. It's been my experience that nothing energizes my creativity more than weekly play with a consistent group of people. To that end, I expect posts about sha-Arthan will increase once the campaigns begin, though I am sure there will be some others throughout this month, as my preparations ramp up after their recent pause.

I spent a good portion of the past weekend working on the character classes of my The Vaults of sha-Arthan science fantasy setting. I'm happy to say I'm nearly finished this document, though the real work will come once I start refereeing the campaign. I'd originally hoped to be doing that this month, but it'll likely have to wait till September, owing to various real life distractions. As I probably mentioned before, the current plan is to run two concurrent campaigns, one through Discord and another through a play-by-post site. My hope is that this will put development of the setting into overdrive as well as put the rules through their paces. It's been my experience that nothing energizes my creativity more than weekly play with a consistent group of people. To that end, I expect posts about sha-Arthan will increase once the campaigns begin, though I am sure there will be some others throughout this month, as my preparations ramp up after their recent pause.August 1, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Lost World

I continue to be amazed by how many foundational works of fantasy and science fiction I haven't yet written about in this series – but then there are a lot authors and stories who've had a powerful influence on the hobby of roleplaying, such as Arthur Conan Doyle. Though most well known for his creation of the consulting detective Sherlock Holmes, Doyle is also responsible for the creation another character, one whose literary adventures have arguably had as great, if not greater, influence on popular culture: Professor Challenger.

I continue to be amazed by how many foundational works of fantasy and science fiction I haven't yet written about in this series – but then there are a lot authors and stories who've had a powerful influence on the hobby of roleplaying, such as Arthur Conan Doyle. Though most well known for his creation of the consulting detective Sherlock Holmes, Doyle is also responsible for the creation another character, one whose literary adventures have arguably had as great, if not greater, influence on popular culture: Professor Challenger.George Edward Challenger is a Scottish professor of anthropology and zoology employed by the British Museum in London. In addition, Challenger is known as an inventor of some ingenuity, making him one of the most significant prototypes for the stock character of adventurer-scientist so beloved in turn of the 20th century popular literature and the later works inspired by it. Challenger makes his first appearance in the 1912 novel, The Lost World, about which I want to talk today, but he appeared in four other stories by Doyle – two more novels and two short stories – in addition to many other tales by later authors.

The Lost World is told from the perspective of Edward Malone, a young man who works as a reporter for the Daily Gazette. Malone is in love with Gladys Hungerton, an intelligent woman with whom he has been friendly for some time before the novel starts but who does not share his affections. When pressed as to why, she tells Malone that she is "in love with somebody else," quickly elaborating that "it's nobody in particular, only an ideal." Malone desperately – and rather pathetically – says that he can change; he is willing to become anything she wants him to be: "teetotal, vegetarian, aeronaut, theosophist, superman," if only she could love him in return. Gladys reproaches him harshly but fairly, telling Malone just the sort of man whom she might love.

"He would be a harder, sterner man, not so ready to adapt himself to a silly girl's whim. But, above all, he must be a man who could do, who could act, who could look Death in the face and have no fear of him, a man of great deeds and strange experiences. It is never a man that I should love, but always the glories he had won; for they would be reflected upon me. Think of Richard Burton! When I read his wife's life of him I could so understand her love! And Lady Stanley! Did you ever read the wonderful last chapter of that book about her husband? These are the sort of men that a woman could worship with all her soul, and yet be the greater, not the less, on account of her love, honored by all the world as the inspirer of noble deeds."

Rather than understand what Gladys was trying to tell him, Malone cavils, telling her, "We can't all be Stanleys or Burtons … besides we don't get the chance – at least, I never had the chance." She tells him "chances are all around you" and Malone takes this as the impetus to "do something in the world."

Energized by his desire to be a man worthy of the esteem of his beloved, Malone sets off. He approaches his editor, McArdle, for advice in finding "anything that had adventure and danger in it." That's when the name of Professor Challenger first comes up. McArdle suggests Malone seek him out for an interview, though he warns him that Challenger is no admirer of reporters, one of whom he assaulted when he started asking impertinent questions about his recent South American expedition.

Malone then presents himself as a student rather a reporter in order to speak with Challenger. The ruse seems to have worked and he meets the famed zoologist.

His appearance made me gasp. I was prepared for something strange, but not for so overpowering a personality as this. It was his size which took one's breath away—his size and his imposing presence. His head was enormous, the largest I have ever seen upon a human being. I am sure that his top-hat, had I ever ventured to don it, would have slipped over me entirely and rested on my shoulders. He had the face and beard which I associate with an Assyrian bull; the former florid, the latter so black as almost to have a suspicion of blue, spade-shaped and rippling down over his chest. The hair was peculiar, plastered down in front in a long, curving wisp over his massive forehead. The eyes were blue-gray under great black tufts, very clear, very critical, and very masterful. A huge spread of shoulders and a chest like a barrel were the other parts of him which appeared above the table, save for two enormous hands covered with long black hair. This and a bellowing, roaring, rumbling voice made up my first impression of the notorious Professor Challenger.

Challenger is no fool and he almost immediately sees through Malone's ruse. He becomes angry and, as he with a previous reporter, the professor attacks Malone and throws him out into the street. This catches the eye of a passing policeman, who intervenes. Despite this, Malone refuses to press charges against Challenger, who looks on him with humor, "Come in! … I've not done with you yet."

Inside once more, Challenger's attitude toward Malone changes. He exacts a commitment to secrecy from him and then tells him about his previous expedition. While in the Amazon, Challenger a "most extraordinary creature.

It was the wild dream of an opium smoker, a vision of delirium. The head was like that of a fowl, the body that of a bloated lizard, the trailing tail was furnished with upward-turned spikes, and the curved back was edged with a high serrated fringe, which looked like a dozen cocks' wattles placed behind each other.

Malone is not sure what to make of this and advances the possibility that the creature might be something more mundane, like an elephant or a tapir. Challenger scoffs at this, pointing out that no elephants exist in South America. No, he explains, what he had seen was in fact a stegosaurus, a living fossil long thought extinct – and there were more like it in the Amazon. That's why he is planning another expedition and he asks Malone to accompany him.

The bulk of The Lost World details the expedition into the titular lost world itself, a region of South America that is home not only to dinosaur but to hostile ape-men as well. Reading it from the vantage point of more than a century later, it's difficult to be as impressed with the novel as one would have been at the time of its initial release. Nevertheless, the ideas that The Lost World introduces were genuinely remarkable in their day, so much so that they influenced generations of writers, who borrowed ideas from it, sometimes without even realizing they were doing so. There's entire genre of literature named for the novel, a genre that continues to be popular to the present day.

None of this is to suggest that The Lost World isn't an enjoyable novel – quite opposite, in fact. Professor Challenger is a terrific character, very different from Doyle's Sherlock Holmes. Likewise, Malone, despite his pathetic introduction, turns out to be a solid protagonist and reader surrogate. Then there's the lost world of the Amazon itself, with its strange inhabitants and sights, all of which Doyle memorably describes. The pace of the novel is slow at times, I won't deny, but the overall story is compelling and the vehicle of Malone's narration helps to overcome some of the slowness. Fans of adventure literature should find it to their taste and anyone with an interest in the roots of fantasy and science fiction should read it as well.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers