James Maliszewski's Blog, page 131

August 30, 2021

White Dwarf: Issue #7

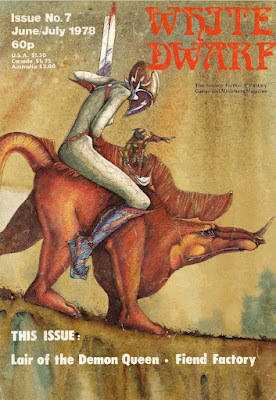

Issue #7 of White Dwarf (June/July 1978) represents something of a milestone for the British gaming periodical. Firstly, it marks the start of the second year of its publication. Secondly, it's the first issue to feature a full-color cover (by the ever-amazing John Blanche). In his opening editorial, Ian Livingstone draws the reader's attention to both of these facts – facts he believes serve as "a reminder to traditional wargamers that we (i.e. roleplayers) are a serious part of the hobby and not just a weird, temporary deviation from it." As ever, I find such comments very strange, but then I was never a wargamer (take a drink), nor did I much care about their opinion of what seemed to me to be a related but wholly separate hobby. Mind you, I was a 10 year-old child when I discovered D&D rather than an adult like Livingstone, so I suppose I can be forgiven for not understanding his seemingly interminable concern about the reputation of roleplaying in wargaming circles. If nothing else, it's a reminder that the past truly is another country.

Issue #7 of White Dwarf (June/July 1978) represents something of a milestone for the British gaming periodical. Firstly, it marks the start of the second year of its publication. Secondly, it's the first issue to feature a full-color cover (by the ever-amazing John Blanche). In his opening editorial, Ian Livingstone draws the reader's attention to both of these facts – facts he believes serve as "a reminder to traditional wargamers that we (i.e. roleplayers) are a serious part of the hobby and not just a weird, temporary deviation from it." As ever, I find such comments very strange, but then I was never a wargamer (take a drink), nor did I much care about their opinion of what seemed to me to be a related but wholly separate hobby. Mind you, I was a 10 year-old child when I discovered D&D rather than an adult like Livingstone, so I suppose I can be forgiven for not understanding his seemingly interminable concern about the reputation of roleplaying in wargaming circles. If nothing else, it's a reminder that the past truly is another country.

The issue begins with an article written by Ed Simbalist entitled "Feudal Economics in Chivalry & Sorcery." It's an interesting enough piece, especially for those who want to more "realistically" model the economics of the European Middle Ages in their campaign settings. More interesting than its content, though, is the fact that it's penned by one of the creators of C&S. If nothing else, Simbalist's appearance in WD's pages show that, after only a year of publication, it had already begun to attract significant attention on the other side of the Atlantic. "Fiend Factory" offers up nine new monsters for D&D, several of which would later appear in the Fiend Folio. None of those featured could be called "classics," even by the odd standards of the Fiend Folio, though a handful deserve comment. The first is the Rover, based on the bouncing ball from The Prisoner. The second is the Gluey, which was renamed the Adherer in its published FF form. Finally, there's the Squonk, based on the legendary monster of northern Pennsylvania, which the text calls "more of a pet than a monster; perhaps the female D&Ders would take more to this beast than the hard-headed males."

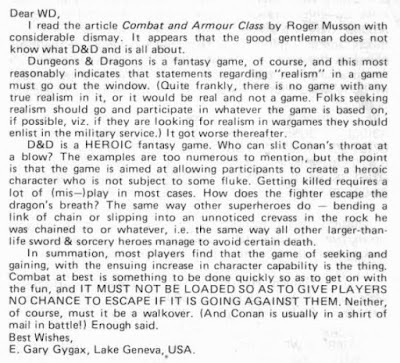

The "Letters" column is notable for one letter, commenting on Roger Musson's article in issue #6. I reproduce it here in its entirety.

One of these days, I'll need to collect together as many Gary Gygax quotes as I can find regarding the matters of "realism" and "heroism" in D&D to see how consistent his position on the matter remained over the years. For now, I'll simply say that, as he often does, Gygax speaks here in such an argumentative and disingenuous fashion that, even if one were inclined to agree with his points (which I mostly do), he makes it hard to do so, lest one be seen as similarly intemperate. I can't help but wonder how different the history of the hobby might have been if the younger Gygax had possessed even a small portion of the equanimity his older self possessed.

One of these days, I'll need to collect together as many Gary Gygax quotes as I can find regarding the matters of "realism" and "heroism" in D&D to see how consistent his position on the matter remained over the years. For now, I'll simply say that, as he often does, Gygax speaks here in such an argumentative and disingenuous fashion that, even if one were inclined to agree with his points (which I mostly do), he makes it hard to do so, lest one be seen as similarly intemperate. I can't help but wonder how different the history of the hobby might have been if the younger Gygax had possessed even a small portion of the equanimity his older self possessed.John T. Sapienza's "Carrying Capacity" offers a short and relatively simple new encumbrance system that uses a character's Strength to determine what percentage of his body weight he can carry in equipment and treasure. Meanwhile, Brian Asbury provides Part III of his "Asbury System" for experience. This time, he gives readers the means to determine the XP value of magic weapons and armor, based on their types (sword, mace, chain, plate, etc.), bonuses, and other abilities. I can see no obvious problem with his system as such, only that it seems like more trouble than it's worth, especially when the Dungeon Masters Guide already does the work for the referee (though, to be fair, at the time of publication of this issue, the DMG was still more than a year in the future).

"Molten Magic" provides photographs for eight different sets of miniature figures, including those by Ral Partha and Asgard. "Open Box," meanwhile, features reviews for The Warlord Game, The Thieves of Fortress Badabaskor, Bifrost Volume 1, Lords and Wizards, The Sorcerer's Cave, and Cosmic Encounter. There's also another installment of the "Kalgar" comic strip, which continues to do little for me. I find myself looking forward to the future, when other strips more familiar to me will appear, but those won't, I fear, appear for quite some time still.

Don Turnbull's "Lair of the Demon Queen" presents a "difficult but rewarding section" of his Greenlands Dungeon for the delectation of readers. The lair is a fairly small section of said dungeon but it's quite well thought out, with an elaborate trap that requires deciphering a poem (spoken by statues with magic mouths) to overcome. I simply adore rooms like this in dungeons and I'm ashamed when I consider how much more straightforward my own chambers tend to be these days. In my youth, I'd devote much thought to tricks and traps, not to mention riddles, rhymes, and other bits of fantasy nonsense intended to aid and befuddle the players. Reading this article reminded me of how far I've fallen in the years since. Perhaps I shall have to rectify this in my future work.

The issue ends with "Thoughts on the Proliferation of Magic Items in D&D" by none other than Gary Gygax. As one might expect, Gygax is very much opposed to what he calls "magic on the cheap," something he claims is quite common in "hobby publications" at the time. He suggests that, since D&D is "designed for a long period of active play," the referee would be wise to give out magic items sparingly and with an eye toward ensuring that the game remain challenging over time. He then offers many strategies for separating PCs from magic treasure so as to maintain the appropriate balance. Everything he says here comports with his writings on the subject elsewhere, but, as I commented earlier, his tone is condescendingly off-putting at times and I fear it might sometimes get in the way of what he intends to say (Physician, heal thyself).

Issue #7 of White Dwarf was, by and large, enjoyable to me. It's definitely step up in terms of presentation and quality over its immediate predecessors and it gives me hope that the upcoming issues will be equally enjoyable.

August 29, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: Strange Eons

One of the dangers of reading an older work is failing to take into account the time in which it was written. By this I mean that it's very easy, from the vantage point of the future, to look at a book – or indeed any cultural artifact – produced in the past and misunderstand its purpose or simply fail to appreciate how it would have been viewed in its own time. For example, I recalled my parents talking about how funny the TV show, Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In, was. When I finally saw an episode of it, many years later, I couldn't fathom what they found so remarkable about it, in large part, I suspect, because I was watching it in the aftermath of its own pop cultural success, when its genuinely clever or original aspects had become so imitated and indeed commonplace that they failed to have any impact on me.

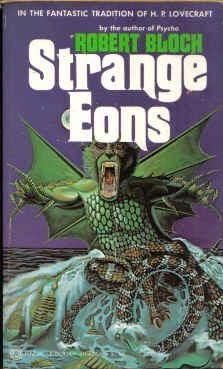

One of the dangers of reading an older work is failing to take into account the time in which it was written. By this I mean that it's very easy, from the vantage point of the future, to look at a book – or indeed any cultural artifact – produced in the past and misunderstand its purpose or simply fail to appreciate how it would have been viewed in its own time. For example, I recalled my parents talking about how funny the TV show, Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In, was. When I finally saw an episode of it, many years later, I couldn't fathom what they found so remarkable about it, in large part, I suspect, because I was watching it in the aftermath of its own pop cultural success, when its genuinely clever or original aspects had become so imitated and indeed commonplace that they failed to have any impact on me. I bring all this up as a prelude to discussing Robert Bloch's novel, Strange Eons. Originally published as a hardcover in 1978 and then, in 1979, as a paperback (the cover of the latter appearing here), the book opens with the following:

This book is dedicated toHPLwho dedicated himself toother outsiders and gaveto them a silver key.

Today, Robert Bloch is probably best known as the author of the 1959 novel, Psycho, on which the 1960 Alfred Hitchcock movie of the same name is based. For present purposes, we should remember that Bloch was a correspondent of H.P. Lovecraft, whose stories he devoured in the pages of Weird Tales. Starting at 1933, when Bloch was fifteen, he wrote regularly to Lovecraft, who not only offered him advice on the craft of writing but also introduced him to other members of his literary circle, such as Clark Ashton Smith and August Derleth. Bloch considered Lovecraft not just his mentor but his friend and was profoundly affected by HPL's death in 1937. In his acceptance speech upon receiving a lifetime achievement award at the First World Fantasy Awards in 1977, Bloch famously talked about this, saying:

"Part of me died with him, I guess, not only because he was not a god, he was mortal, that is true, but because he had so little recognition in his own lifetime. There were no novels or collections published, no great realization, even here in Providence, of what was lost."

This is the context in which one should understand Strange Eons. Bloch felt an immense debt to Lovecraft and his ideas, which, at the time this novel was published, were still not well known outside horror circles. This is in stark contrast to today, when Lovecraft is, if not exactly a household name, better known, his ideas and creations even more so. Strange Eons is, then, a labor of love intended to honor his deceased mentor and popularize some of his themes.

Sadly, Strange Eons is not a very good novel. It is, after a fashion, an intermittently enjoyable one, but it's not one of Bloch's best efforts and, even as an attempt at pulpy popularization of Lovecraftian ideas, it's nothing special. Partly, I think, it's because Bloch indulges in one of the more tired conceits associated with post-Lovecraft Lovecraftian fiction: that HPL's stories were true – or at least based on true events. Bloch wasn't the first (or, sadly, the last) author to make use of this notion, but it's always struck me as equal parts lazy and absurd. It's true that one of the foundations of Lovecraftian cosmic horror is its attempted realism, the suggestion that the events its stories describe occur in our rational, scientific world rather than in some fantasy fairyland. However, that's a far cry from claiming that those same events are, literally, real. I realize that not everyone is as bothered by this conceit as I, but the fact remains that I am and I think this undermines the plot of Strange Eons.

The novel is divided into three sections, all of which ultimately relate to one another and the central mystery of the novel. The first section concerns an art collector named Albert Keith, who comes upon a bizarre painting that turns out to be the painting from "Pickman's Model." Keith has never heard of this story but his friend, Simon Waverly, has and he tells him all about it. Naturally, Keith doesn't believe in ghouls, let alone the idea that an obscure pulp writer from the Depression had written a story about this very painting he'd just purchased. This leads to a disagreement between the two men, a disagreement that reiterates my points above about the nature of this novel.

"Then there's only one answer. The work was an artist's homage, a sincere tribute. The painting was inspired by Lovecraft's story."

"Suppose it was the other way around." Waverly spoke slowly, softly. "Suppose Lovecraft's story was inspired by the painting?"

Over time, Keith starts to become more convinced that there's something to Waverly's hypothesis, as the two of them become embroiled in the activities of a secretive group who want the painting and are willing to go to any length to acquire it, including murder. Or multiple murders, as it turns out, with many of them staged in such a way as to evoke the events of other stories by Lovecraft, such as "The Lurking Fear." As Keith slowly comes round to Waverly's way of thinking, this affords Bloch the chance to hold forth on Lovecraft's life, personality, interest, and the subject of his stories – all things most readers today would know well but that a reader in 1978 might not. The result is forced and clunky, however affectionately meant, and it slows down the pacing of the first section considerably.

The second section is the longest and takes place six months after the first one and focuses on Kay Keith, Albert's ex-wife, who works as a model. She gets an offer to do some work for the Starry Wisdom Temple, which has now established itself in Los Angeles. The Temple is led by a Reverend Nye, a dark-skinned man with a strange accent Kay can't place. If that sounds ridiculous, it is, even in context, and it only becomes more so as Bloch once again launches into long disquisitions on Lovecraft's life, the Cthulhu Mythos, and innumerable 1970s pop occultism themes, like ancient astronauts, pyramid power, and the like. Section three takes place thirty years in the future and concerns the events leading up to the coming of Cthulhu and the end of the world.

As I said, Strange Eons is not a good novel by most definitions but it does evince a lurid glee that some might nevertheless find appealing. Even so, I find it hard to speak badly of it, because it's very clear that Robert Bloch wrote it out of respect and admiration for H.P. Lovecraft, to whom, even four decades after his death, he owed a great debt. He no doubt intended Strange Eons as a gateway drug for those who hadn't yet encountered the work of his master, which, in 1978, would have been a great many people indeed. I find that genuinely praiseworthy; it's just a pity the novel doesn't live up to its high goal.

August 28, 2021

Jack the Clever

I honestly can't recall the first time I saw the adjective "Vancian" used to describe the magic system of Dungeons & Dragons. It might have been in the pages of Dragon, but I can't be certain. Wherever it was, I was initially baffled by it, because I didn't read any of Vance's work until after I had started playing RPGs. When I first picked it up, I associated D&D with Robert E. Howard's Hyborian Age, Fritz Leiber's Nehwon, and J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth. The influence of any one of these authors on the game seemed so much more obvious to me at the time, but Jack Vance? Who was he?

I honestly can't recall the first time I saw the adjective "Vancian" used to describe the magic system of Dungeons & Dragons. It might have been in the pages of Dragon, but I can't be certain. Wherever it was, I was initially baffled by it, because I didn't read any of Vance's work until after I had started playing RPGs. When I first picked it up, I associated D&D with Robert E. Howard's Hyborian Age, Fritz Leiber's Nehwon, and J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth. The influence of any one of these authors on the game seemed so much more obvious to me at the time, but Jack Vance? Who was he?Fortunately for my literary education, I eventually picked up a copy of The Dying Earth and soon fell in love with its delightful combination of "high" vocabulary, picaresque adventures, and wondrous setting. Vance was an unexpected surprise to me at the time. I'd read several authors whose works contained elements I'd also found in Vance – such as Clark Ashton Smith's penchant for archaisms – but I'd never found them all in those of a single author before. So impressed was I that I immediately sought out its follow-up, The Eyes of the Overworld, which likewise impressed me and sent me on a quest to read everything by Vance I could get my hands on.

I bring all this up because today is the 105th anniversary of the birth of John Holbrook Vance. Born in San Francisco in 1916, Vance led a remarkable life. During the Great Depression, he took up a variety of menial jobs to support himself and his mother, during which time he also attended university, eventually graduating in 1942. During World War II, he joined the Merchant Marine, an experience that led his lifelong love of sailing and the sea. Throughout this time, he made his first efforts at published writing in science fiction and fantasy, genres he had loved since he was a teenager. By the end of the 1940s, Vance started to achieve success as a writer, which encouraged him to devote himself to the craft fulltime. The rest, as they say, is history.

There's a great deal that could be said about Jack Vance and his influence on fantasy, science fiction, and the hobby of roleplaying. Rather than do that at this time, I will instead urge you to read one of his many stories. Whether you choose one of his Dying Earth tales, the Lyonesse trilogy, the Planet of Adventure series, or almost any other with his byline, you'll find joyful stories tinged with melancholy and wild, unpredictable imagination presented through singular prose. Vance is truly one of the Giants of fantasy fiction and he deserves to celebrated by all who appreciate superb writing and creativity.

Happy Birthday, Mr Vance.

August 25, 2021

Retrospective: Trouble Brewing

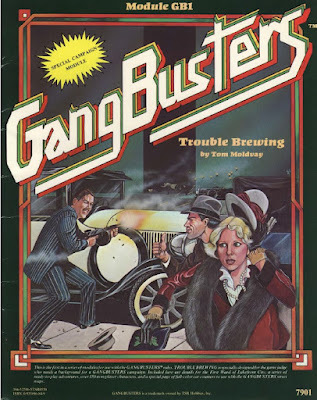

Gangbusters was a favorite RPG of mine in my youth, but I've long had the impression that not a lot of people took notice of it when it was released. That's too bad, because, in addition to its original boxed set being terrific on its own, TSR published a number of truly superb follow-up products to support it, most of them adventure scenarios. The one that wasn't was 1982's Trouble Brewing, written by none other than Tom Moldvay and, much like

Murder in Harmony

by Mark Acres, it made a lasting impression on me.

Gangbusters was a favorite RPG of mine in my youth, but I've long had the impression that not a lot of people took notice of it when it was released. That's too bad, because, in addition to its original boxed set being terrific on its own, TSR published a number of truly superb follow-up products to support it, most of them adventure scenarios. The one that wasn't was 1982's Trouble Brewing, written by none other than Tom Moldvay and, much like

Murder in Harmony

by Mark Acres, it made a lasting impression on me.Trouble Brewing bills itself as a "special campaign supplement" and that's a very apt description, as we'll see. Like most TSR modules of its era, this one is a 32-page staple-bound booklet wrapped in a removable, four-sided, cardboard cover. Both the booklet and the cover are memorably illustrated by the late, great Jim Holloway, whose combination of realism and humor seems perfect for the module's subject matter. Jeff Easley also contributes a couple of pieces, but they are, sadly, not nearly so memorable. Oddly, the back panel of the cover features a collection of cut-out cars, trucks, and other vehicles for use with the street map included in the original boxed set. I never understood why TSR did this, since cutting up the cover is a poor option and, being color, the counters didn't photocopy well, given the technology of the era.

The bulk of the booklet consists of information on Lakefront City – the game's ersatz Chicago – and its most important inhabitants, complete with game statistics. While this might seem dull, it's not. Moldvay does a great job in giving all the characters, from the heads of the important criminal gangs to the local government and law enforcement right down to butchers and hardware store owners, a degree of individuality that's very helpful to a referee. Many of them even includes small details that could easily be turned to the creation of scenarios, like the fact that the widowed jeweler Saul Goldstein has secretly left his business to his employee, Fred Russell, in his will or that one of the waitresses at Velma's Restaurant is secretly the daughter of the second in command of the O'Connor Gang. Little of it is earthshattering or even particularly imaginative but it's helpful, especially to inexperienced referees looking to instill some life into their campaigns.

Another aspect of this section of the booklet that's worth pointing out is the fact that a great many of the character descriptions are of "average" citizens of Lakefront City rather than of "important" people, such as politicians or gangsters. This is very helpful in my experience, since it not only helps bring the setting to life but also gives the referee the tools he needs in the event the player characters wander into a barber shop or five-in-dime store unconnected with the current scenario. As someone who has struggled such matters in urban adventures, I recognize the value in books like this.

In addition to the details of Lakefront City itself, Trouble Brewing also includes an extensive campaign outline. This outline consists of a variety of scenarios intended for use with different types of characters, such as gangsters, law enforcement, even investigative reporters. Though each scenario can be played on its own, each forms part of a larger campaign scenario that deals with the brewing turf war between Al Tolino and Deanie O'Connor, as they vie with one another for control of the city's lucrative criminal enterprises. This is very useful to the referee on many levels, not least being that it affords players the opportunity to play out this campaign from a variety of different angles. This flexibility and open-endedness is to be commended in my opinion. I know I learned a lot from its presentation in my youth.

If I have a criticism of Trouble Brewing, it's that it's set in a fictional city rather than a real world one, but I fully understand why this was done. When I was younger, this bothered me a great deal, as I wanted to learn more about, say, Chicago or New York's gang wars during the 1920s. The advantage of a fictional locale is that there's no need for a great deal of research, nor is there any expectation that events will unfold just as they did in our world. Still, my preference, then and now, is for real history over imaginary history and it's one of the few qualms I have about what is otherwise a very well done and useful module for use with Gangbusters.

August 23, 2021

White Dwarf: Issue #6

Issue #6 of White Dwarf (April/May 1978) features a cover by Chris Beaumont. Looking at Beaumont's piece, I finally realized how much I like these early WD covers – not so much for the art in all cases but for the use of a single background color, which I find very striking. Apparently, I needed reminding that I prefer simple, amateurish covers like those of older gaming products. Speaking of the past, I note Ian Livingstone's editorial, in which he boasts of the fact that, starting with this issue, the text is now right justified. It's easy to laugh at this from the vantage point of the 21st century, but, in 1978, this would have been a genuinely big deal, especially for a amateur/semi-pro magazine like White Dwarf.

Issue #6 of White Dwarf (April/May 1978) features a cover by Chris Beaumont. Looking at Beaumont's piece, I finally realized how much I like these early WD covers – not so much for the art in all cases but for the use of a single background color, which I find very striking. Apparently, I needed reminding that I prefer simple, amateurish covers like those of older gaming products. Speaking of the past, I note Ian Livingstone's editorial, in which he boasts of the fact that, starting with this issue, the text is now right justified. It's easy to laugh at this from the vantage point of the 21st century, but, in 1978, this would have been a genuinely big deal, especially for a amateur/semi-pro magazine like White Dwarf."Combat and Armour Class" by Roger Musson is a lengthy examination of the concept of AC in Dungeons & Dragons and proposes various options and house rules to it. Many of the options should be familiar with longstanding players of D&D, such as making it viable for fighters to go largely or lightly unarmored like the heroes of pulp fantasy. More interesting (to me anyway) is Musson's proposal of a series of death saving throws when a character drops below 0 hit points. This approach or something similar to it has become quite widespread in recent years, but Musson came up with this idea in 1978.

"The Fiend Factory" is a collection of seven new monsters for use with D&D. The monsters, created by Ian Livingstone, Roger Musson, and Trevor Graver, are (mostly) familiar to anyone who's made use of the Fiend Folio. "Archive Miniatures" by John Norris is a review of the aforesaid miniatures, of which Norris thinks very highly. Meanwhile, Lewis Pulsipher offers "A Place in the Wilderness," a short article that provides D&D game statistics for creatures derived from Jack Vance's novel, The Dragon Masters. "Open Box" provides reviews of Knights of the Round Table (Little Soldier), Elric (Chaosium), Wilderlands of High Fantasy (Judges Guild), Dungeon Decor and Labyrinthine (both by Falchion Products), and The Endless Dungeon (Wee Warriors). With only a couple of exceptions, I'd never heard of most of these products – but then there have been so many wargaming and RPG products published in the last half-century, that's far from surprising.

Also reviewed is GDW's Traveller, in this case by Don Turnbull in a three-page article that covers every aspect of the game. By and large, Turnbull is favorably impressed by the game. However, he points out two things he considers serious omissions. First, Turnbull wishes there were more examples of pre-generated material for use by the referee. In this, he compares Traveller unfavorably to Metamorphosis Alpha, which is, frankly, a strange thing to do. Nevertheless, I can see his point, at least broadly. Second, Turnbull points out that there are no rules for creating or playing nonhuman aliens. That's a fair point, though I would counter that Traveller was largely inspired by the humanocentric science fiction of the decades immediately following the Second World War and thus it makes sense that

There's another installment of David Lloyd's "Kalgar" comic, as well as some magic items for D&D by Duncan Campbell. Martin Easterbrook provides yet another "Hit Location in Melee" article. It's not a terrible system, as it goes, but I'm generally of the mind that D&D's inflationary hit points system isn't really compatible with a more "realistic" approach to hit location. The philosophy behind the two approaches are very different and it'd be better to stick with either D&D's approach or, say, that of RuneQuest rather than trying to hybridize them. Brian Asbury continues to detail his alternate experience point system, this time with awards for spellcasting based on the character level and the spell level. While I understand the logic behind such awards – I've been hearing defenses of it my whole time as a roleplayer – I've never been a fan. Asbury's system seems skewed toward providing more XP to lower-level casters and, again, I understand the logic behind it, but it does little to convince me of the value of adopting his overall approach.

And, with that, we're done another issue of White Dwarf. What strikes me most about this issue is the way it highlights that the first few years after the release of Dungeons & Dragons were filled reckless experimentation with the game's rules. House rules, variants, and options abound, many of them not at all to my taste. Nevertheless, it's good to see the extent to which the earliest players and referees saw scope for adding to – or "improving" in their eyes – D&D. This is at the heart of why I think roleplaying games are such remarkable pastimes: they encourage creative engagement with them in a way that boardgames and video games rarely do (cue howls to then contrary in the comments). So, while this is far from my favorite issue of White Dwarf thus far, I nevertheless found it satisfying and look forward to what is coming in the future.

The Emperor of Dreams

Immense fan though I am of both H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, when it comes to the writers of pulp fantasy, there can be no question that my favorite remains Clark Ashton Smith. Precisely why this is so is somewhat difficult to say, but, were I forced to nail it down, I would say that its a combination of Smith's incantatory language and the overwhelming sense of melancholy that pervades so much of his work. I tend toward the melancholic myself, which no doubt explains the powerful hold so many of Smith's stories exercise over my imagination. Even more powerful than that, however, is his ability to transport the reader to other worlds wholly unlike our own. Whereas both Lovecraft and Howard could be called, to varying degrees, "realists," which is to say, writers whose tales are grounded in the real world, Smith's stories are very often pure fantasies with little or no connection to mundane existence whatsoever.

Immense fan though I am of both H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, when it comes to the writers of pulp fantasy, there can be no question that my favorite remains Clark Ashton Smith. Precisely why this is so is somewhat difficult to say, but, were I forced to nail it down, I would say that its a combination of Smith's incantatory language and the overwhelming sense of melancholy that pervades so much of his work. I tend toward the melancholic myself, which no doubt explains the powerful hold so many of Smith's stories exercise over my imagination. Even more powerful than that, however, is his ability to transport the reader to other worlds wholly unlike our own. Whereas both Lovecraft and Howard could be called, to varying degrees, "realists," which is to say, writers whose tales are grounded in the real world, Smith's stories are very often pure fantasies with little or no connection to mundane existence whatsoever.Interestingly, this is a point that is also made in The Emperor of Dreams, a 2018 documentary about the life and work of the Bard of Auburn. Written and directed by Darin Coelho Spring and released through Hippocampus Press, the film is simply delightful – everything I could have hoped for in a documentary of this kind. At slightly less than two hours in length, The Emperor of Dreams is able to take its time, allowing Smith's story to unfold at its own pace rather than being rushed. There are sections devoted to every period of Smith's life, from his precocious youth to his adulthood as a pulp fantasy writer to his later life as a sculptor and doyen of the growing field of science fiction and fantasy. Watching this, one truly gets a picture of the whole of Smith's remarkable life, aided by the careful selection of still and moving photography of people and places important to him and his development as one of the great outsider artists of the 20th century.

Equally important to the success of The Emperor of Dreams are the reflections and commentaries on Smith by scholars and admirers, starting with Harlan Ellison, who credits Smith's "The City of the Singing Flame" with putting him on the path of becoming a writer. Also interviewed are Donald Sydney-Fryer, who actually met Smith; Ron Hilger, Scott Connors, and S.T. Joshi, among many others (like the psychedelic artist Skinner). Their thoughts and reminiscences about Smith are insightful and at times touching and they do much to elevate the documentary above a mere recounting of the events of Smith's life and times (however valuable that information is). The Emperor of Dreams is thus a celebration of Clark Ashton Smith and his evocations of the weird in poetry, fiction, and art more broadly.

I already knew a fair amount about Smith's life and works, but I still learned a great deal about him from this film. I knew, for example, that Smith had been a protégé of the Bohemian poet George Sterling, but I did not know that there ultimate falling out occurred as a Smith's writing "The Abominations of Yondo" which Sterling considered unworthy of his talent. Likewise, I had never heard the story of how Smith first took up sculpting or had rejected high school in favor of educating himself by reading books in the Auburn Public Library instead. The movie is filled with such details, along with stories told about him by his stepson that only add to my appreciation of the man. There's even an audio recording of Smith reciting some of his own poetry. If only there had been film footage of something similar!

If you're at all interested in Clark Ashton Smith's life, The Emperor of Dreams is well worth a watch. I somehow did not know it existed until just a few days ago, but am I ever glad that I corrected this lacuna in my education. Very good stuff!

House of Worms, Sessions 236–237

As the festivities celebrating the marriage of Nebússa and Lady Srüna wound down, both Znayáshu and Keléno took this as an opportunity to learn more about just what had motivated Kéttukal to approach Grujúng and what, if any, role Elué hiDlarútu, the so-called "Belle of Béy Sü" had in these proceedings. Znayáshu moved first. He ventured out onto the courtyard of the Golden Bough clanhouse where the athletic competitions were taking place. At a safe distance, he tried to observe the activities of Kéttukal, and his "nephew" Kágesh (in reality, Prince Eselné traveling incognito). They seemed to be engaged in a disagreement of some sort, albeit a friendly one, which caught his attention.

He moved in closer, hoping that he could make use of his clairaudience spell to hear their conversation. That was precisely when Elué glided outside and joined the two men. This caught Znayáshu's attention immediately; he was now even more determined to hear what they were saying. Unfortunately for him, by the time he successfully cast his spell – unseen, thank the gods – their discussions had nearly ended. All he was able to overhear was Elué tell the pair, "When you're finished with these pointless martial displays, please come inside. There are other people I'd like you to meet." Eselné scoffed, "I'll go where I like and meet whom I like. Do not forget that." To this, Kéttukal replied, "We've already done as you asked. Can you not leave us in peace?" Elué said nothing and returned inside.

Seeing how the woman – from a medium-ranked clan, no less – behaved toward an imperial prince and the foremost general of the Empire shocked Znayáshu to such an extant that he abandoned his use of clairaudience, opting instead to cast seeing other planes on Elué (and hoping she would not take notice). He succeeded in his efforts and the spell revealed that the woman was a powerful nexus of otherplanar energy, though the exact nature of these energies eluded him. He moved to follow Elué, when he noticed that Keléno was approaching her of his own accord. Znayáshu then attempted to hide himself in one of the side rooms so that he could get closer to the two of them and continue his use of the spell. Sadly for him, he was noticed by Elué herself, who gave him a stern look that suggested she knew what he was attempting. Rather than risk trouble, he removed himself from the scene and rejoined Aíthfo and Grujúng, who were enjoying themselves in another chamber.

Keléno boldly asked Elué about her intentions in having previously warned Aíthfo of an attack upon his person. Smiling, she explained that her interest was in ensuring that no harm would come to "such an interesting man." When pressed, she asked Keléno if he would be willing to speak in one of the smaller adjoining rooms where they "could speak freely." Keléno agreed and Elué led him into a darkened room where she spoke quite frankly. She explained that "your activities on the Southern Continent have attracted a great deal of attention, not all of it good. You may not realize it, but you have inadvertently interfered with the plans of men of great power. Your current patron may not be able to protect you." By this, she meant Prince Mridóbu, who dwelled in Avánthar and was responsible for sending them to Linyaró nearly three years ago. "You might be better served by switching your allegiance to someone who could better protect you."

Fearing that this conversation was leading in a dangerous direction, Keléno extemporized. He explained that he agreed with Elué's assessment but that he would need time to convince his clan mates and comrades of this. Elué seemed pleased and said that she would call upon him again in three days to see if he had been successful in swaying his companions. Keléno then dismissed himself from her presence and rushed to the others. He told them that they would need to make preparations to leave Béy Sü as soon as possible. This had already been their theoretical plan, but matters now demanded they escape the capital before matters came to a head. Word was then passed to everyone involved, including Nebússa and Srüna, to meet at the Palace of the Realm early that morning.

Collecting their gear and other belongings, the House of Worms members and their allies called upon Di'iqén hiSayúncha, the prefect of the Palace. They gave him the letter Prince Mridóbu had issued them, which permitted them access to the tubeway car station beneath the capital. Di'iqén was impressed and said he would be happy to oblige them. Nevertheless, the prefect peppered them with probing questions about the nature of their activities, questions the characters chose not to answer. Though Di'iqén claimed to understand – "Imperial security and all that." – he seemed to be trying to delay their departure, something that worried Keléno a great deal. Nebússa then invoked his status as an agent of the Omnipotent Azure Legion to cow the prefect, who then took them through a series of rooms and down staircases that led into the underworld beneath Béy Sü.

The journey below took close to an hour, during which time the characters observed shadowy figures moving about in other areas of the underworld. The figures did not approach them or otherwise interfere with their descent, but there was some worry that they might have been spies of another imperial faction or secret society. Once they reached the tubeway car station, they sent Di'iqén away, which he eventually did, albeit reluctantly. The characters then summoned a car, as they had in the past, only to see that it was a small one – insufficient to carry all of their entourage. They sent their men-at-arms away, along with all but one of the sorcerers who'd traveled with them. Only Lára hiKhánuma remained.

Once inside the tubecar, the characters inserted the travel disk that was supposed to take them to the Naqsái city-state of Miktatáin. Instead of departing immediately, a voice – in the language of the Ancients, they presumed – said something twice from within the controls of the car. Then, a series of images and symbols appeared on a view screen. This led to some concern, since, the last time they had visited Miktatáin, they had drained all the power from its tubeway station. Perhaps the voice was saying that the station was no longer reachable. Regardless, the car did not move, nor did its door close.

Keléno then decided, with some reluctance, to contact Toneshkéthu, the third stage student at the College at the End of Time, whom they had aided in the past (or was it the future?). She had given Keléno an arcane device by which to speak with her in times of need, though she warned against using it too often, out of concern that it would "do damage to your branch of the Tree of Time." When contacted, they asked her the meaning of the words being spoken by the tubecar. Toneshkéthu seemed somewhat annoyed, asking "Didn't you pay attention during your lessons at the College?" before saying "Oh, wait; that hasn't happened … I mean: never mind." She then quickly said, "The voice is saying that there's a blockage and would you be willing to accept an alternate route to the destination rather than the most direct one. Just touch the screen on the right hand side and the car should operate."

Sure enough, Toneshkéthu's advice was correct and the car hurtled toward its destination. However, after about twenty minutes of travel, the voice spoke again, saying something different. The car began to slow in its acceleration before finally stopping at a station. This station was not the one beneath Miktatáin. The door to the car opened and several people got out to look around. The station was dark, except for a light coming from a nearby corridor. There were also footprints in the dust – four-footed prints that suggested those of the Ssú. Needless to say, this filled no one with pleasure, but it was not certain what they should do, since the car was no longer moving and had not ejected their transport disk.

Kirktá encouraged Keléno to contact Toneshkéthu once more, which he was not certain was a good idea. Without other options, though, he did it. Clearly irritated, she asked, "What now?" Keléno explained their situation and she said, "The car is over its weight capacity and needs time to recharge before being able to proceed again. In fifteen minutes, it should again be able to take you toward your destination." Relieved, Keléno thanked her and promised not to contact her again soon. Kirktá used this opportunity to study the symbols on the screen, hoping to gain a greater understanding of the numbering system of the Ancients, aided by the control of self spell.

After nearly fifteen minutes had elapsed, everyone returned to the tubecar and waited for its door to close once more. It did so and the car hurtled on toward – they hoped – Miktatáin and the Achgé Peninsula.

August 22, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Lurking Fear

Since H.P. Lovecraft's 131st birthday was just a few days ago, it seemed only right that the next installment of this series should highlight one of his works. Of course, after nearly 250 entries, many of them featuring HPL's stories, it can be difficult to find a Lovecraftian tale I haven't yet discussed. Fortunately for us, Grampa Theobald was prolific and left us with a many excellent choices, such as "The Lurking Fear," the subject of today's post.

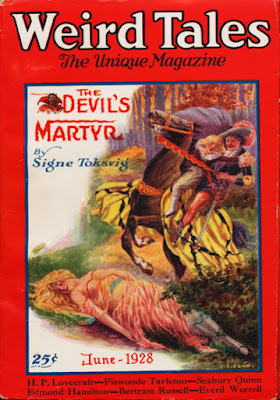

Since H.P. Lovecraft's 131st birthday was just a few days ago, it seemed only right that the next installment of this series should highlight one of his works. Of course, after nearly 250 entries, many of them featuring HPL's stories, it can be difficult to find a Lovecraftian tale I haven't yet discussed. Fortunately for us, Grampa Theobald was prolific and left us with a many excellent choices, such as "The Lurking Fear," the subject of today's post."The Lurking Fear" was originally released as a four-part serial in Home Brew between January and April 1923. It was later reprinted in its entirety in the June 1928 issue of Weird Tales. There are no significant textual differences between the two versions of the story. However, the 1923 serial is notable for including illustrations (two per installment) by none other than Clark Ashton Smith. These illustrations are, in the words of S.T. Joshi, "very curious line drawings" of trees and vegetation. HPL apparently didn't think much of these drawings, as they didn't depict anything described in his story.

Like so many Lovecraft stories, "The Lurking Fear" is told in the first person by an unnamed narrator, in this case a journalist whose "love of the grotesque and the terrible … has made my career a series of quests for strange horrors in literature and in life." Accompanied by "two faithful and muscular men" named Bennett and Tobey, the narrator is exploring a "deserted mansion atop Tempest Mountain to find the lurking fear." Tempest Mountain is located in the Catskills of southeastern New York and the eponymous lurking fear the narrator seeks is reputedly

a daemon which seized lone wayfarers after dark, either carrying them off or leaving them in a frightful state of gnawed dismemberment.The narrator is not the first reporter to be drawn to this part of rural New York. Just a month prior to the start of the tale, "an eldritch panic" had seized the area, when

One summer night, after a thunderstorm of unprecedented violence, the countryside was aroused by a squatter stampede which no mere delusion could create. The pitiful throngs of natives shrieked and whined of the unnamable horror which had descended upon them, and they were not doubted. They had no seen it, but had heard such cries from one of their hamlets that they knew a creeping death had come.

In the morning citizens and state troopers followed the shuddering mountaineers to the place where they said the death had come. Death was indeed there. The ground under one of the squatters' villages had caved in after a lightning stroke, destroying several of the malodorous shanties; but upon this property damage was superimposed an organic devastation which paled it to insignificance. Of a possible seventy-five natives who had inhabited this spot, not one living specimen was visible. The disordered earth was covered with blood and human debris bespeaking too vividly the ravages of daemon teeth and talons; yet no visible trail led away from the carnage.

This horror baffled the authorities and reporters alike. The locals, however, knew it was the lurking fear, the exact nature of which varied from telling to telling. The one thing all tellings agreed upon was that the lurking fear "dwelt in the shunned and deserted Martense mansion" which is why the narrator and his compatriots were determined to explore it long after all other investigators had left the scene of the horrific massacre of mountaineers described above.

Being "a connoisseur of horrors," the narrator and his two armed companions made their way to the Martense mansion to determine whether the legendary lurking fear was a "solid entity or vaporous pestilence." Once there, they set themselves up in one of the old house's rooms on the second floor and waited. They also made use of the room's large window to monitor the grounds. If there were any truth that this place was indeed the lair of the lurking fear, they would take note of it. Further, the three men took turns keeping watch through the night so that there was no chance they'd be caught unawares – or miss a clue that might help them uncover the truth of what was happening on Tempest Mountain.

The narrator is awakened from his turn to sleep by a "devastating stroke of lightning which shook the whole mountain." He finds himself alone, Bennett and Tobey nowhere to be found. Instead, he sees, in the "flash of a monstrous fireball," a frightful sight,

a blasphemous abnormality from hell's nethermost craters; a nameless, shapeless abomination which no mind could fully grasp and no pen even partly describe.

The narrator flees back to his hotel room in a nearby town, but is haunted by what might have happened to his companions. Because of this, he decides he must resume his investigations, no matter what the consequences.

"The Lurking Fear" is an early story by Lovecraft and it shows. More so than most of his later output, this is truly a pulp story, filled with melodrama and hackneyed turns of phrase. Despite that, there's a great deal to recommend it, not least being the Martense mansion itself, a classic "huge ruined pile" of the sort that could easily appear in a D&D adventure. Without revealing too much, I will say here that the narrator isn't wholly wrong to see the mansion as the seat of the lurking fear but there is much more happening than he realizes, the revelation of which is surprisingly effective, the story's literary shortcomings notwithstanding. In addition, "The Lurking Fear" touches upon themes to which Lovecraft will return again and again throughout his writing career, such as the weight of history and physical degeneration. Reading "The Lurking Fear" is thus an opportunity to see H.P. Lovecraft before he was fully the H.P. Lovecraft whose name is forever linked to the genre of cosmic horror he bequeathed to the world.

August 20, 2021

"Thou are not gone ..."

It had long been my practice here to commemorate the births of writers whose work has been influential on both myself and the hobby of roleplaying more generally. When I returned to Grognardia last year, I failed to do this, largely due to the forgetfulness of middle age (and simply being out of the practice of regular blogging). This being the 131st anniversary of the birth of Howard Philips Lovecraft, it seemed appropriate to re-dedicate myself to this tradition today.

It had long been my practice here to commemorate the births of writers whose work has been influential on both myself and the hobby of roleplaying more generally. When I returned to Grognardia last year, I failed to do this, largely due to the forgetfulness of middle age (and simply being out of the practice of regular blogging). This being the 131st anniversary of the birth of Howard Philips Lovecraft, it seemed appropriate to re-dedicate myself to this tradition today.There are a couple of reasons why I chose to do so. First, and most obviously, it was simply convenient. Lovecraft's birthday just happened to be at hand and so it made sense to take advantage of it. Second, and more importantly, Lovecraft's influence looms large in the hobby, so large in fact that many don't even realize the creative debt they owe to the "Old Gent." In my estimation, Lovecraft is just as important as J.R.R. Tolkien when it comes to his contributions to the cauldron of concepts out of which contemporary fantasy arose.

Without HPL, there'd be no (or at least fewer) tentacled monstrosities from beyond space time or blasphemous tomes containing truths Man was not meant to know to cite just two very rather superficial examples of ideas he either created or popularized. More significant, I think, are his themes, such as the insignificance of mankind, the vastness of the uncaring universe, and the double edged sword of scientific knowledge, most of which have infiltrated our popular culture to the point where few give them much thought anymore. To varying degrees, all of us in this hobby are Lovecraft's intellectual descendants to one degree or another, no matter how much we might deny it.

Though today is the anniversary of Lovecraft's birth, I nevertheless find myself on these occasions thinking instead of Clark Ashton Smith's elegy "To Howard Phillips Lovecraft," written just thirteen days after HPL's death in 1937. While I find the whole poem quite poignant, I have always been particularly moved by several lines toward the end that grasp at something similar to the overall point of this post.

Lo! in this little interim of daysHow far thy feet are spedUpon the fabulous and mooted waysWhere walk the mythic dead!For us the grief, for us the mystery. . . .And yet thou art not goneNor given wholly unto dream and dust:For, even uponThis lonely western hill of AveroigneThy flesh had never visited,I meet some wise and sentient wraith of thee,Some undeparting presence, gracious and august.More luminous for thee the vernal grass,More magically dark the Druid stone,And in the mind thou art forever shownAs in a magic glass;And from the spirit's page thy runes can never pass.

August 19, 2021

Random Roll: PHB, p. 7

As I mentioned in a previous post, I mentioned a section at the start of the AD&D Players Handbook entitled simply "The Game." It's a fascinating section, because it lays out, over the course of about a dozen paragraphs, Gary Gygax's understanding of not just AD&D but roleplaying – and RPG campaigns – in very broad terms. There's a lot of insight to be gleaned from this section, which is why I'm returning to it again this week.

As with most other role playing games, this one is not just a single-experience contest. It is an ongoing campaign, with each playing session related to the next by results and participant characters who go from episode to episode.

The importance of the campaign is something I've been emphasizing over the course of the last year. I've grown ever more convinced that it's the key to understanding Gygaxian (and probably Arnesonian) D&D and that that understanding can in turn be applied to many other early roleplaying games (like Empire of the Petal Throne and Traveller, to name two with which I am very familiar). In fact, I am increasingly of the opinion that it's impossible to play D&D as intended outside of the context of a long campaign.

As players build the experience level of their characters and go forth seeking ever greater challenges, they must face stronger monsters and more difficult problems (and here the Dungeon Master must likewise increase his or her ability and inventiveness).

This and what immediately follows is an echo of things Gygax says in the Dungeon Masters Guide. I wish to draw attention to his invocation of "inventiveness." He is absolutely right to do so, as it's one of the keys to ensuring continued player interest over the course of months and years. I very much doubt that my House of Worms campaign, now just shy of six and a half years of active play, would have lasted as long as it has had I not continually demonstrated the kind of inventiveness Gygax recommends.

While initial adventuring usually takes place in an underworld setting, play gradually expands to encompass other such dungeons, town and city activities, wilderness explorations, and journeys into other dimensions, planes, times, worlds, and so forth.

This is a superb summation of the expected development of a Dungeons & Dragons campaign and the one for which the game's design works best. That's not to say that other approaches cannot be used successfully – they certainly can – but the progression that Gygax outlines here is, I think, the surest path to campaign longevity and enjoyment. I think it noteworthy that he mentions "journeys into other dimensions, planes, times, worlds" as the kinds of places where higher-level characters seek adventure.

Players will add characters to their initial adventurer as the milieu expands so that each might actually have several characters, each involved in some separate and distinct adventure form, busily engaged in the game at the same moment of "Game Time." This allows participation by many players in games which are substantially different from game to game as dungeon, metropolitan, and outdoor settings are rotated from playing to playing.

This is another aspect of old school play that I think is forgotten nowadays: the play of multiple characters. In my House of Worms campaign, this is not unusual. Most of the players have several characters whom they can play at any given time, depending on what is happening in the session. For example, the player of the scholarly priest of Sárku, Keléno, played a crotchety navigator named Váshur when some of the characters set off on an extended sea voyage around the east coast of the Achgé Peninsula. Months went by as that voyage continued and Keléno, though one of the original characters of the campaign, was not played. Eventually, focus shifted back – both in space and time – to the city of Linyaró, where Keléno remained, and his player again took him up again (and the other players assumed the roles of others who remained behind with him). This "back and forth" is quite common in our campaign and has, I firmly believe, contributed to its health and longevity.

And perhaps a war between players will be going on (with battles actually fought out on the tabletop with miniature figures) one night, while on the next, characters of these two contending players are helping each other survive somewhere in a wilderness.

Now, this is something I've yet to see in any of my recent campaigns. The characters of the House of Worms are a tight-knit bunch and, for the most part, their disagreements are ephemeral. That said, Tékumel is full of secret societies and clandestine factions, some of whom have attempted to recruit the PCs. It's certainly possible that, one day, as they continue to rise in power and influence within the Tsolyáni Empire, they might come to blows.

In the meantime, though, what's very clear – and what Gygax alludes to here – is that, in a good campaign, the players can take on many roles, each distinct and each adding to the depth and texture of the whole. While I am very fond of saying that "the referee is a player too," a corollary to this is that "players are world-builders too." By this I mean only that no campaign should be so tightly controlled that there is not room for creative contributions by the players. If anything, a referee should welcome such contributions and afford opportunities for them whenever possible. This has happened too many times to count in the House of Worms campaign and it's all the better for it.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers