James Maliszewski's Blog, page 127

November 1, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Seven Black Priests

My love for Fritz Leiber's tales of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser know few bounds. As I've written on numerous previous occasions, I consider them perhaps the closest, in terms of content and, above all, feel to Gary Gygax's vision of the implied setting of Dungeons & Dragons. More than that, the Twain themselves behave in ways that remind me of the antics of player characters in a long-running and interesting campaign. This reveals most clearly in their interactions with one another. Steadfast friends who can be completely relied upon in moments of danger, Fafhrd and the Mouser nevertheless quibble and squabble with one another. They get on each others' nerves and sometimes even come to momentary blows – but, in the end, the reader knows they'll always be there when the going gets rough. That's probably why I consider them among the most appealing characters ever to appear in the annals of fantasy literature.

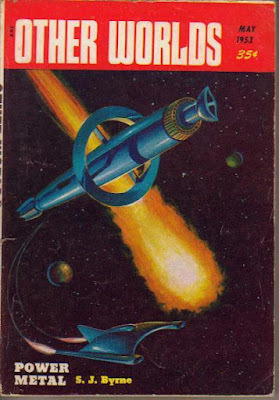

My love for Fritz Leiber's tales of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser know few bounds. As I've written on numerous previous occasions, I consider them perhaps the closest, in terms of content and, above all, feel to Gary Gygax's vision of the implied setting of Dungeons & Dragons. More than that, the Twain themselves behave in ways that remind me of the antics of player characters in a long-running and interesting campaign. This reveals most clearly in their interactions with one another. Steadfast friends who can be completely relied upon in moments of danger, Fafhrd and the Mouser nevertheless quibble and squabble with one another. They get on each others' nerves and sometimes even come to momentary blows – but, in the end, the reader knows they'll always be there when the going gets rough. That's probably why I consider them among the most appealing characters ever to appear in the annals of fantasy literature."The Seven Black Priests" first appeared in the May 1953 issue of Other Worlds, one of several magazines edited by Ray Palmer after his legendary run as editor of Amazing Stories. The story is initially told from the perspective of one of the eponymous priests, who finds himself drawn to "the rumble of singing" he hears in the snowy expanse near the Cold Waste. The source of the singing, we soon learn, is none other than Fafhrd, who is attempting to cheer up his friend, who did not like the snow and ice as he did.

The aforementioned priest studies the pair for a short time before leaping, dagger drawn, upon them. A brief fight ensues, during which the priest slips and falls into a chasm, seemingly to his death. The Mouser is puzzled, both by why this man would suddenly attack them but also by his appearance: his skin was completely black.

"But what was he?" the Mouser asked frowningly. "He looked like a man of Klesh."

"Yes, with the jungles of Klesh as far from here as the moon," Fafhrd reminded him with a chuckle. "Some maddened hermit frostbitten black, no doubt. There are strange skulkers in these little hills, they say."

The Mouser peered up the dizzily mile-high cliff and spotted the nearby niche. "I wonder if there are more of him?" he questioned uneasily.

As they get closer to the Cold Waste and its lava vents, they spot a "green hill with a glitter." Looking closer, they see that "there rose from it a stubby pillar of rock almost like an altar."

But something else was foremost in the Mouser's thoughts.

"The eye, Fafhrd. The glad, glittering eye!" he whispered, dropping his voice as though they were in a crowded street and some informer or rival thief might overhear. "Only once before have I seen such a gleam, and that was by moonlight, across a king's treasure chamber. That time I did not come away with a huge diamond. A guardian serpent prevented it. I killed the wiggler, but its hiss brought other guards.

"But this time there's only a little hill to climb. And if at this distance the gem gleams so bright, Fafhrd" – his hand dropped and gripped his companion's leg, at the sensitive point just above the knee, for emphasis – "think how big!"

Excited by the prospect of looting the diamond he is sure is there, the Mouser "went skipping gaily" toward his prize, while Fafhrd "followed more slowly, gazing steadily at the green hill." When the two of meet at the base of the hill, the Mouser finds "a flat, dark rock covered with gashes" that Fafhrd immediately recognizes as "the runes of tropic Klesh." If nothing else, this proves the man who attacked them probably was a Kleshite and not some madman blackened by frostbite. Together, they attempt to decipher the runes.

"The seven black …" Fafhrd read laboriously.

"... priests," the Mouser finished for him. "They're in it, whoever they may be. And a god or beast or devil – that writing hieroglyph means any one of the three, depending on the surrounding words, which I don't understand. It's very ancient writing. And the seven black priests are to serve the writhing hieroglyph, or to bind it – again either might be meant, or both."

"And so long as the priesthood endures," Fafhrd took up, "that long will the god-beast-devil lie quietly … or sleep … or stay dead … or not come up."

Reading all this makes the Mouser uneasy, who claims he has "lost [his] hunger" for the gem, dismissing it as "likely just a bit of quartz." Unfortunately for him, Fafhrd declares he has "only now worked up a good appetite" and determines to climb the hill and reach the gem, ominous Kleshite runes be damned.

Needless to say, the gem is no ordinary diamond and the message of the runes is indeed a warning. The Twain's attempt to steal it results in the appearance of the seven black priests – "The six," Mouser reminds Fafhrd and the reader, "We killed one of them last night." – all of whom are dedicated to stopping them. Why they do this and indeed why they are so far from their southern home forms the remainder of the story, which is rollicking good bit of pulp fantasy.

"The Seven Black Priests" is perhaps a little more humorous and little less grim than some of Leiber's efforts, but it still stands head and shoulders above most other yarns of this kind. In large part, that's because, as I stated at the start of this post, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are such delightfully realized characters. I enjoyed reading about their exploits no matter what they are doing and this story is no different. As exciting as the situations Leiber describes frequently are, it's his protagonists that keep me coming back for more – but then I would expect nothing less from the greatest thieves in all of Lankhmar!

October 29, 2021

REVIEW: The Spine of Night

One of the many oddities of contemporary popular culture is that, while fantasy, in the broad sense, has never been more popular, the sword-and-sorcery tales that were once the standard bearers of the genre in the 1960s and '70s don't get quite as much play. With the exception of the disappointing 2011 Conan the Barbarian, I can't think of a single sword-and-sorcery movie released in the last decade. Beyond that, I'd have to reach back to the early years of this century or even into the 1990s to think of films that could reasonably be called by that name. That's a shame, because I think many of sword-and-sorcery's signature elements and themes, most notably its meditations on the ambiguity of barbarism, civilization, and magic, might resonate well with viewers at this moment in history.

One of the many oddities of contemporary popular culture is that, while fantasy, in the broad sense, has never been more popular, the sword-and-sorcery tales that were once the standard bearers of the genre in the 1960s and '70s don't get quite as much play. With the exception of the disappointing 2011 Conan the Barbarian, I can't think of a single sword-and-sorcery movie released in the last decade. Beyond that, I'd have to reach back to the early years of this century or even into the 1990s to think of films that could reasonably be called by that name. That's a shame, because I think many of sword-and-sorcery's signature elements and themes, most notably its meditations on the ambiguity of barbarism, civilization, and magic, might resonate well with viewers at this moment in history.Writer-directors Philip Gelatt and Morgan Galen King would seem to agree. Their film, The Spine of Night, which was released today in theaters and through a number of video on demand services, is an engaging attempt to tell a sword-and-sorcery tale in an original setting. It's presented as a rotoscoped animated movie, after the fashion of Ralph Bakshi's Wizards, The Lord of the Rings, and Fire and Ice, and, of course, Gerald Potterton's Heavy Metal. If you're at all familiar with any of these previous works, particularly Heavy Metal and Fire and Ice, you'll have a better sense of what you're in for. The Spine of Night is an unambiguously adult film, with heavy doses of graphic violence and nudity (two of its main characters appear wholly or partially unclothed throughout). There's little gratuitous or prurient about this, however; their inclusion serves to establish the world and the story Gelatt and King wish to tell.

That story is a complex one, told through a series of vignettes tied together by a larger framing device. True to its sword-and-sorcery literary inspirations, The Spine of Night proceeds briskly and with little time spent to luxuriate in exposition. Combined with its shifting perspective and occasional use of unique words and names, the viewer must pay close attention to the unfolding narrative to understand it fully. That said, the movie rarely fails to offer up compelling characters and intriguing situations, making this task a little easier, especially if you are already a fan of sword-and-sorcery yarns.

The Spine of Night begins with the ascent of the swamp witch Tzod (voiced by Lucy Lawless) to the top of a mountain during a snowstorm. About her neck she wears a necklace on which hangs a bone and a blue flower – exactly like the one she finds withering at the top of the mountain. Before she can reach this second flower, she finds that it protected by a masked warrior (Richard E. Grant), who threatens her for what he sees as her attempt to steal "the last light of the gods." The Guardian is startled to learn Tzod already possesses a flower of her own asks how she came to possess it. She explains that a single seed of the flower blew down the mountain, took root, and grew. That flower then spread and is the cause of much of the trouble that has occurred in the world beyond. The Guardian knows nothing of this; he has kept watch over the single dying flower on the mountaintop for untold eons.

What then follows is Tzod's recounting to the Guardian of what she knows of events since the fateful day when she and her people were defeated by outsiders seeking to expand their empire. At that time, Tzod's necklace was made up of many flowers, whose power she used to heal and to protect. Captured, she is taken to the fortress of Lord Pyrantin (Patton Oswalt), the petulant son of the the empire's unnamed leader. There, she also meets a timid scholar named Ghal-Sur (Jordan Douglas Smith). He's a member of a not-quite-religious order who scours the world for lost knowledge. He's been summoned here to record the acts of Pyrantin. However, when he sees the power the blue flowers hold, he schemes to steal them away from Tzod and thereby set into motion a series of events that unfold over the course of an indeterminate but apparently long period of time.

The blue flowers are thus a major through-line in the The Spine of Night. Over the course of its vignettes, we learn more about them and their origins. Each vignette set in a different place and largely involves different characters. For example, one vignette is set in the city from which Ghal-Sur's order comes, while another takes place in a city besieged by enemy forces. Each story provides the viewer with a piece of a large picture, detailing not just the unfolding events Tzod is describing to the Guardian but also the world in which The Spine of Night is set. The vignettes vary in length but all add something to the overall narrative of the film. The same is true of the characters who appear in them. It's an interesting approach to storytelling for a film. Gelatt and King clearly want to show us as much of the world they've created as they can while still telling a coherent story and I think they largely succeed in doing so.

The voice cast is good. All three principal characters are well acted, with Richard E. Grant's Guardian being a standout. It's from him that some of the film's best moments come, such as when he reveals the origins of both the world and the blue flowers. He conveys the right balance between menace, genuine concern for mankind, and weariness of his long vigil. This is a credit to the movie's script, which is uniformly excellent. It's neither inappropriately contemporary in its dialog nor does it stray into the forced "ye olde timey" verbiage all too common in fantasy. If the film has any weaknesses, it's that it might be a bit too short for the story it is trying to tell. On the other hand, as I noted earlier, this may be a deliberate choice in homage to the spare prose of many sword-and-sorcery tales of the past. I should also add that, while the animation is solid – assuming one appreciates rotoscoping – it's not quite up to the level of its visual inspirations. That's probably a consequence of its budget more than anything else and I find it difficult to fault the film for it.

Those small criticisms aside, The Spine of Night thoroughly engaged me. I enjoyed the movie's look and feel, the story it told, and the world in which it was set. In fact, I found myself frequently wishing that more time had been spent with several of the locales and characters introduced in the various vignettes. A great deal was implied in these small stories and I'd love see some of those implications elaborated upon in greater detail. The conclusion of the movie suggests that Gelatt and King might have more to say about their setting and I devoutly hope that that is so. The Spine of Night is an intriguing, imaginative fantasy of the kind I'd like to see more often. Here's hoping that we do!

October 27, 2021

Retrospective: Bloodstone Pass

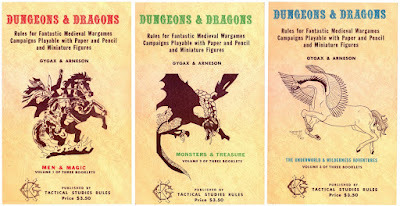

When Dungeons & Dragons first appeared in 1974, it bore the subtitle "Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns Playable with Paper and Pencil and Miniature Figures." Nowhere in the game's three little brown books does the word "roleplaying" appear, though, as Gary Gygax pointed out, it was quite common for miniatures wargamers to roleplay the leaders and other important figures of their tabletop armies. And, of course, many roleplayers have, in the course of their adventures and campaigns, turned to miniatures rules to aid them in adjudicating mass battles. These two hobbies are forever intertwined with one another, to the point where it's often difficult to determine with any ease where one begins and the other ends.

When Dungeons & Dragons first appeared in 1974, it bore the subtitle "Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns Playable with Paper and Pencil and Miniature Figures." Nowhere in the game's three little brown books does the word "roleplaying" appear, though, as Gary Gygax pointed out, it was quite common for miniatures wargamers to roleplay the leaders and other important figures of their tabletop armies. And, of course, many roleplayers have, in the course of their adventures and campaigns, turned to miniatures rules to aid them in adjudicating mass battles. These two hobbies are forever intertwined with one another, to the point where it's often difficult to determine with any ease where one begins and the other ends.I've long had a fascination with miniatures wargaming, though I've never really delved too deeply into it. In my campaigns of old, there were occasional mass combats, but I rarely made use of actual miniatures wargame rules to handle them. Instead, I simply extrapolated – not always felicitously – from the base rules of whatever RPG I was playing (usually some flavor of D&D). That's why I welcomed the appearance of TSR's Battle System boxed set in 1985: I hoped they might save me the trouble of having to figure out a relatively painless way to handle large engagements of men and monsters in AD&D.

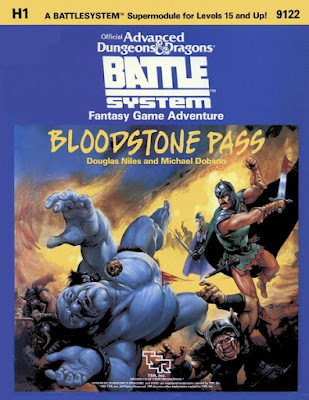

For a while in my early teens, I used Battle System often and had a lot of fun with it. Though my affection for it eventually waned, that wasn't before I had the chance to make use of the first module published to support it, Bloodstone Pass. Written by Douglas Niles and Michael Dobson, module H1 is called a "supermodule" and intended for use with characters of level 15 and above. I presume it was called a supermodule because it came in a thin box and was filled with more than 100 cardboard counters and a dozen fold-up buildings, in addition to the expected 32-page scenario (and Battle System unit roster book). It's a fairly impressive package overall, since it provides the referee with everything he needs to run not just the adventure itself but all the mass battles that occur during its events.

That was certainly the appeal to me at the time. Though I owned quite a few miniatures (mostly Grenadier's AD&D line), I didn't have anywhere close to enough of them to field a proper army on the tabletop. Between the original Battle System box and Bloodstone Pass, though, I now had more than enough cardboard counters to handle the hordes of evil humanoids I'd always imagined as the enemies in any fantasy battle. Likewise, though the fold-up buildings weren't as impressive looking as the sorts of models I sometimes saw in hobby stores or at local games days, they nevertheless served their purpose. More to the point, I was able to build them myself without too much trouble, which was their true value. Whatever else Bloodstone Pass was, it was a godsend to a kid like myself, who lacked the skills, patience, and funds to put together a large and attractive collection of miniatures and terrain.

As for the adventure itself, Bloodstone Pass is nothing special. It's yet another riff on the well worn tale of the Seven Samurai, with the player characters being enlisted to protect the mostly defenseless village of Bloodstone against an Evil Army of Evil. It's all very straightforward and clichéd – primarily a backdrop against which to play out some fun miniatures battles. There's absolutely nothing wrong with that. I remember enjoying myself greatly back in the day; the relative lack of anything more deep probably didn't even occur to me at the time. Even now, I almost feel as if it's a cheap shot to criticize Bloodstone Pass for working as intended. The module was, after all, meant to support the newly-released Battle System and encourage AD&D players to make use of it in their own campaigns. Mission accomplished!

October 26, 2021

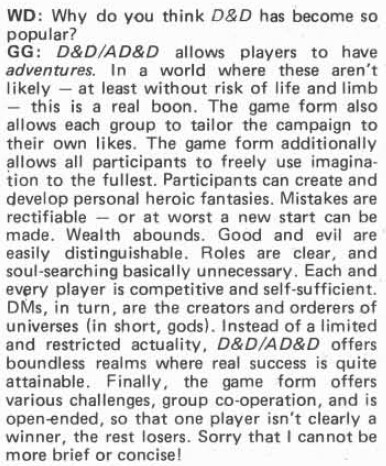

White Dwarf Interviews Gary Gygax

Issue #14 of White Dwarf features a long interview with Gary Gygax by Ian Livingstone. As I mentioned in my earlier post, it's a surprisingly good interview in which Gygax says a few things I don't believe I've ever read anywhere else. For instance, when asked about "the original inspiration for D&D," Gygax responds in this way:

Issue #14 of White Dwarf features a long interview with Gary Gygax by Ian Livingstone. As I mentioned in my earlier post, it's a surprisingly good interview in which Gygax says a few things I don't believe I've ever read anywhere else. For instance, when asked about "the original inspiration for D&D," Gygax responds in this way:CHAINMAIL, then Dave Arneson's campaign and Dave Megarry's game DUNGEON!

It's a short answer but it says a lot. The importance of Chainmail is well known and obvious. The significance of Arneson's pre-D&D Blackmoor campaign is likewise widely acknowledged (though the fact that Gygax so readily admits this in late 1979 is, I think, notable). The role of Dave Megarry's boardgame, on the other hand, is often forgotten nowadays. That's in part an accident of publishing history: Dungeon! as a game predates D&D but it didn't appear in published form until after OD&D appeared in 1974.

Shortly afterward, Livingstone asks Gygax about how he applied "the concept of role-playing to the novel game theme of fantasy." Gygax replies that "role-playing is common in wargaming," especially at 1:1 scale, so it wasn't a huge leap. Fantasy, meanwhile, isn't really all that novel.

Most of us, after all, are raised on fairy tales, fantasy, and myth. With that background, I actually don't view fantasy gaming as a novel idea, really, and I marvel that it wasn't done before D&D!Of course, as Gygax already admitted, it was done before D&D, by Arneson and his crew in the Twin Cities. There are also other examples of proto-FRPGs prior to 1974, such as the Lankhmar games Fritz Leiber played with Harry Fischer, but none of them, including Blackmoor, saw print until after TSR published OD&D. (As an aside, Gygax implies that Guidon Games might have published it, if it had not folded beforehand and Avalon Hill was "luke warm to suggestions about fantasy.")

Livingstone then asks Gygax about the appeal of D&D and the kinds of people who enjoy playing it. What Gygax says is quite interesting, some of it echoing things he'd said elsewhere. He starts by describing the qualities of a "good D&D player" as follows:

Imaginative retentive memory, competitive, co-operative, thorough, bold (but not rash), and quick thinking … Slightly suspicious can be added and logical and deductive reasoning powers are most useful too.

This exchange follows (which I reproduce in its entirety):

Over the years, Gygax repeatedly made reference to the way that roleplaying games enabled ordinary people to have "adventures" in a way that was largely impossible in the contemporary world. He felt that was very important, especially for children, and, the older I get, the more I see the rightness of his belief.

Over the years, Gygax repeatedly made reference to the way that roleplaying games enabled ordinary people to have "adventures" in a way that was largely impossible in the contemporary world. He felt that was very important, especially for children, and, the older I get, the more I see the rightness of his belief. The remainder of the interview talks about D&D's prominence in the world of RPGs – Gygax is dismissive of its "imitators" – the deleterious effect of most fan-made material on the game ("rubbish"), the place of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, his Greyhawk campaign, and his inability to play as often as he would like. As I said, it's a decent interview from a period when TSR was just on the cusp of the huge success that would propel it even farther ahead of its rivals. Gygax thus speaks with a certain degree of confidence, even swagger, but the gamer in him has not yet been fully subsumed within his "TSR Gary" persona. He is still very much the guy who enjoys playing all kinds of games and wants nothing more than to share that love with others, even as he evinces a certain degree of prickliness at the notion of anyone else horning in on "his" territory as the creator and purveyor of the world's first and most successful RPG. From the vantage point of history, it's clear that many of Gygax's strengths were the very things that, in other contexts, proved to be his weaknesses – but then so it is with all men.

The remainder of the interview talks about D&D's prominence in the world of RPGs – Gygax is dismissive of its "imitators" – the deleterious effect of most fan-made material on the game ("rubbish"), the place of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, his Greyhawk campaign, and his inability to play as often as he would like. As I said, it's a decent interview from a period when TSR was just on the cusp of the huge success that would propel it even farther ahead of its rivals. Gygax thus speaks with a certain degree of confidence, even swagger, but the gamer in him has not yet been fully subsumed within his "TSR Gary" persona. He is still very much the guy who enjoys playing all kinds of games and wants nothing more than to share that love with others, even as he evinces a certain degree of prickliness at the notion of anyone else horning in on "his" territory as the creator and purveyor of the world's first and most successful RPG. From the vantage point of history, it's clear that many of Gygax's strengths were the very things that, in other contexts, proved to be his weaknesses – but then so it is with all men.

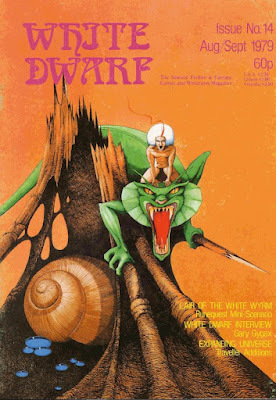

White Dwarf: Issue #14

Issue #14 of White Dwarf (August/September 1979) sports an unusual cover by Emmanuel, best known for the iconic cover of the Fiend Folio. Ian Livingstone's editorial compares US and UK game conventions, with particular attention paid to the length (typically three days in the US vs one in the UK) and expense (US conventions cost more) of these gatherings. Not being much of a convention goer myself – even less so in these crazy times – my opinion on the matter probably doesn't much matter. Still, I can't say that the increasingly theme park-like atmosphere of major game conventions holds much appeal to me. I'd much rather attend something smaller and more "restrained," but what do I know?

Issue #14 of White Dwarf (August/September 1979) sports an unusual cover by Emmanuel, best known for the iconic cover of the Fiend Folio. Ian Livingstone's editorial compares US and UK game conventions, with particular attention paid to the length (typically three days in the US vs one in the UK) and expense (US conventions cost more) of these gatherings. Not being much of a convention goer myself – even less so in these crazy times – my opinion on the matter probably doesn't much matter. Still, I can't say that the increasingly theme park-like atmosphere of major game conventions holds much appeal to me. I'd much rather attend something smaller and more "restrained," but what do I know?Part 2 of Andy Slack's excellent "Expanding Universe" article for Traveller appears here. This time, Slack offers rules additions for starships, computers, and all manner of weaponry, including nuclear ones. Like Part 1, this is excellent, full of both good ideas and good sense. There's a reason why Slack was – and is, in my book anyway – one of the stand-out writers for White Dwarf in its early years. "The Fiend Factory" offers up five more monsters for D&D. Interestingly, none of them seems to be among those chosen for inclusion in the Fiend Folio.

"Open Box" provides three reviews. The first tackles two supplements for GDW's Traveller: Mercenary and 1001 Characters. The reviewer, Don Turnbull, thinks quite highly of the former and less of the latter. I find it fascinating that Turnbull notes that there are some who find perhaps the most inspired part of the Traveller rules – character generation – to be tedious and it's for these misguided souls that 1001 Characters would be most appealing. Turnbull also reviews two Judges Guild products, Dragon Crown and Of Skulls and Scrapfaggot Green. He considers Of Skulls the better of the two, but nevertheless criticizes the quality, both of content and production, of JG's releases when compared to those of TSR. Jim Donohoe gives Chaosium's Balastor's Barracks a very middling review (5 out of 10). He never explains why he rated it thus, but I know from my own experience that it's a dull slog of a dungeon for RuneQuest that gives little indication of the glories that would later appear for that game line.

"Lair of the White Worm" by John Bethell is a "mini-scenario" for RQ. Set in the ruins of a Dragonewt colony that reputedly sheltered a young wyrm, the locale is a two level affair, consisting of 24 chambers. It's not bad for what it is, though it certainly lacks the attention to world building that would come to characterize most Gloranthan materials (both fan-made and published by Chaosium). "Treasure Chest" presents two elaborate traps after the fashion of Grimtooth's Traps and a series of connected rooms filled with tricks and traps called "The Bath-House of the Pharaoh." These are quite clever and remind me that I need to do a better job of creating compelling traps for use in my fantasy games.

The issue ends with a lengthy interview with none other than Gary Gygax himself. The interview contains enough fascinating material that I'm going to save its contents for a second post I'll make later today. Suffice it to say that, as is so often the case, Gygax gives a good interview, the exact content of which depends greatly on when he was interviewed and by whom. In this case, I get the impression that Gygax must have felt well at ease and so was a great deal more frank about several topics than I would have expected. That said, he nevertheless pushes the "AD&D is a completely different game from OD&D" line that he has elsewhere, no doubt in an effort to shore up TSR's legal defense against Dave Arneson's lawsuits. Still, it's a good interview, as you'll see.

October 25, 2021

The Winner and Still Champion

Last night, while writing, I was suddenly struck with a realization that, while not particularly notable in and of itself, nevertheless says a great deal about the state of our shared hobby and the industry that supports it, to wit: Isn't it interesting that, as we approach the half-century mark since the release of Dungeons & Dragons, D&D remains the most successful and popular RPG of all time?

Last night, while writing, I was suddenly struck with a realization that, while not particularly notable in and of itself, nevertheless says a great deal about the state of our shared hobby and the industry that supports it, to wit: Isn't it interesting that, as we approach the half-century mark since the release of Dungeons & Dragons, D&D remains the most successful and popular RPG of all time? In all my life, there has never truly been a rival to D&D, at least not a long-lasting one – and this is in spite of the fact the game has frequently been mismanaged by its current custodians. You'd think that, after nearly five decades, someone would have come up with a RPG to challenge D&D in terms of sales or pop cultural influence, but I don't see much evidence that this is so (feel free to correct me in the comments). I wonder why that is. What is it about Dungeons & Dragons that keeps it on top of the heap?

October 24, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: Can These Bones Live?

With Halloween less than a week away, I found my thoughts drifting toward "spooky" stories I could discuss in this week's installment of Pulp Fantasy Library. There were a lot of good candidates – some of which might appear in the coming weeks – but the one that most excited me was Manly Wade Wellman's "Can These Bones Live?," a short story featuring the Appalachian balladeer, Silver John.

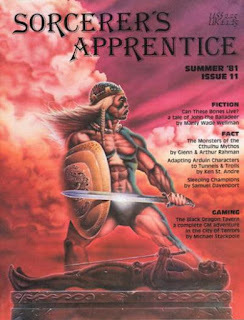

With Halloween less than a week away, I found my thoughts drifting toward "spooky" stories I could discuss in this week's installment of Pulp Fantasy Library. There were a lot of good candidates – some of which might appear in the coming weeks – but the one that most excited me was Manly Wade Wellman's "Can These Bones Live?," a short story featuring the Appalachian balladeer, Silver John.

Now, I'm a huge fan of Wellman's fiction in general and the stories of John in particular, but what was the deciding factor in my decision was the publication where it first appeared: Sorcerer's Apprentice (issue #11/summer 1981, to be precise). For those unfamiliar with this periodical, Sorcerer's Apprentice was published by Flying Buffalo in support of its fantasy roleplaying game, Tunnels & Trolls. Original fiction by established fantasy and science fiction authors was a common feature of many gaming magazines in the 1970s and '80s and Sorcerer's Apprentice was no different.

While traveling, John encounters "eight men in rough country clothes" carrying "a big chest of new-sawed planks" that measured "nine feet long and three feet wide and another three high." One of the men, Embro Hallcott by name, approaches John and asks him his name and business.

"Well, mostly I study things. This morning, back yonder at that settlement, I heard tell about a big skeleton that turned up on a Chaw Hollow farm."

"You a government man?" the grizzled one inquired of me.

"You mean, look for blockade stills?" I shook my head. "Not me. Call me a truth seeker, somebody who wonders himself about riddles in this life."

John's a character about which Wellman tells us little. Like most good pulp fantasy protagonists, his origins and history are largely unimportant. All that matters is that he's here, where something interesting is about to occur. In this case, that something interesting is the burial of the aforementioned big skeleton. John helps the eight men carry the chest holding it half a mile to Stumber Creek Church.

The preacher, Travis Melick, is a gaunt man "in a jimswinger coat, a-carrying a book covered with black leather." Though he's never met John, he knows him by reputation, having "heard of good things [he'd] done." The approbation of the preacher reassures Hallcott and his fellows, he were still somewhat suspicious of the guitar-toting stranger.

The men heave the chest – a massive coffin really – toward the graveyard, where a fresh grave has already been made for it. Before burying it, one of the men, called Oat, asks that it be opened first, since that is "the true old way." John then peers inside.

The bones inside were loose from one another and half-wrapped in a Turkey Track quilt, but I saw they were laid out in order. They were big, the way Hallcott had said, big enough for an almighty big bear. I had a notion that the arms were right long; maybe all the bones were long. Thick, too. The skull at the head of the coffin was like a big gourd, with caves of eyeholes and two rows of big, lean teeth, Hallcott banged the lid shut and hooked it again.

With that out of the way, Melick begins the burial rite for "the remains of a poor lost creature," a rite that involves quoting from the Book of Ezekiel (from which the title of the short story comes). Afterwards, the men lower the coffin into the grave and they depart. Melick asks John if he'll be his guest for the night, but he puts him off, saying he wants to "wait here a spell."

Hallcott takes notice of this fact and asks John why he wishes to stay at the gravesite rather than leave like everyone else. John doesn't offer a solid explanation. Instead, he talks about the Book of Ezekiel and the many oddities in it – living bones, flying wheels, and the like. Hallcott agrees there are "strange doings in Ezekiel" and the two men settle down for a nighttime vigil together. They pass the time eating sandwiches and pondering the big skeleton they buried.

"I reckon you'll agree with me, them bones we buried were right curious. Great big ones, and long arms, like on an ape."

"Or maybe on Sasquatch," I said. "Or Bigfoot."

"You believe in them tales?"

"I always wonder myself if there's not truth in air tale. And as for bones – I recollect something the Indians called Kalu, off in a place named Hosea's Hollow. Bones a-rattling 'round, and sure death to a natural man."

"You believe that, too?"

"Believe it? I saw it happen one time. Only Kalu got somebody else, not me."

"Can these bones live?" Hallcott repeated the text.

I trust it won't come as a surprise to anyone to reveal that, yes, these bones can live and the remainder of the yarn is spent the consequences of that. Like most of Wellman's Silver John stories, this one is charmingly told in a folksy, understated way that evokes the tension of a good ghost story. The reader won't be frightened down to his bones, but he might well be transported to the woods, hunkered down around the campfire to hold off the chilly night air, while shadows dance and strange sounds echo. "Can These Bones Live?" is thus a genuinely effective short story and a reminder of why Wellman is rightly considered one of the masters of pulp fantasy.

October 21, 2021

Random Roll: DMG, pp. 57–58

At the bottom of page 57 of the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide, there's a section entitled "Travel in the Known Planes of Existence." The section continues onto page 58, but, even so, it's relatively brief, occupying only five paragraphs in total. Nevertheless, it's Gary Gygax's lengthiest discussion of this topic in the DMG and is thus worthy of some attention.

He begins:

The Known Planes of Existence, as depicted in APPENDIX IV of the PLAYERS HANDBOOK, offer nearly endless possibilities for AD&D play, although some of these new realms will no longer be fantasy as found in swords & sorcery or myth but verge on that of science fiction, horror, or just about anything else desired.

Gygax says something here I'd like to comment upon. Significantly, I think, he notes that the Planes "offer nearly endless possibilities for AD&D play." Over the course of his time overseeing AD&D, he regularly said similar things, often adding that he saw the Planes as the next logical step in the progression of a campaign beyond domain-level play. Yet – much like domain-level play, actually – Gygaxian AD&D provided almost no real guidance on how to run adventures in these otherworldly realms. Nearly everything written about the Planes in 1e was penned by someone else, starting with 1980's Queen of the Demonweb Pits, the first AD&D adventure set beyond the Prime Material Plane.

Now, I understand the historical reasons why Gygax likely did not do so. The demands of running TSR during the height of the D&D fad, not to mention his later sojourn to California, no doubt distracted him. Even so, I can't help but feel that if, as he repeatedly said, he considered the Planes to be the locales of D&D's ultimate adventures, he should have prioritized discussion of the matter. It's especially puzzling that he didn't given that we know that he refereed adventures of this sort in his own Greyhawk campaign. It's a pity we don't know more about them, as they'd probably have given us some insight into his view of high-level campaigns and scenarios.

The known planes are a part of the "multiverse". In the Prime Material Plane are countless suns, planets, galaxies, universes. So too there are endless parallel worlds. What then of the Outer Planes? Certainly, they can be differently populated if not substantially different in form.

As a younger person, I found it quite fascinating the Prime Material Plane, as conceived by Gygax, is so vast in scope. If it is so then surely the Outer Planes are similarly vast.

Spells, magic devices, artifacts, and relics are known ways to travel to the planes. You can add machines or creatures which will also allow such travel. As far as the universe around your campaign world goes, who is to say that it is not possible to mount a roc and fly to the moon(s)? or perhaps to another planet? Again, are the stars actually suns at a distance? or are they the tiny lights of some vast dome? The hows and wherefores are yours to handle, but more important is what is on the other end of the route?

Re-reading this paragraph still inspires wonder in me. The idea of mounting a giant bird and flying into space, for example, is delightful and in keeping with very expansive notion of fantasy that once reigned supreme, before the crabbed demands of marketing contracted it.

For those of you who haven't really thought about it, the so-called planes are your ticket to creativity, and I mean that with a capital C! Everything can be absolutely different, save for those common denominators necessary to the existence of the player characters coming to the plane. Movement and scale can be different; so can combat and morale. Creatures can have more or different attributes. As long as the player characters can somehow relate to it all, then it will work.

Have we ever seen a conception of the planes like this in any version of Dungeons & Dragons? If so, I cannot recall it. For example, Roger E. Moore's article on the Astral Plane, which appeared in the pages of Dragon, could have and indeed should have been a step in this direction, but instead it was interminably dull, saved only by the accompanying adventure, Fedifensor by Robert Allen, which takes some advantage of the weird "geography" of the place. It's a pity, because, as Gygax rightly notes, the planes are indeed the referee's ticket to creativity.

This is not to say that you are expected to actually make each and every plane a totally new experience – an impossibly tall order. It does mean that you can put your imagination to work on devising a single extraordinary plane. For the rest, simply use AD&D with minor quirks, petty differences, and so forth.While I am sympathetic to Gygax's larger point, I nevertheless feel that he did referees a disservice by not exhorting them to greater heights of creativity and providing examples of how he did this in his own campaign. I can't help but imagine that the subsequent history not just of D&D but of the pop cultural fantasy descended from or influenced by it might have been different if he had – a less earthbound and more fantastical "vanilla" fantasy perhaps!

If your players wish to spend most of their time visiting other planes (and this could come to pass after a year or more of play) then you will be hard pressed unless you rely upon other game systems to fill the gaps. Herein I have recommended that BOOT HILL and GAMMA WORLD be used in campaigns. There is also METAMORPHOSIS ALPHA, TRACTICS, and all sorts of other offerings which can be converted to man-to-man role-playing scenarios. While as of this particular writing there are no commercially available "other planes" modules, I am certain that there will be soon – it is simply too big an opportunity to pass up, and the need is great.

Would that there had been more such modules! Regardless, I do find Gygax's suggestions regarding to use other RPG rules compelling, as they go some way toward demonstrating just how different another plane might be. Instead, most commercially available treatments of the planes have reduced them to, say, modifying how magic spells work rather than something much more ambitious and genuinely wondrous.

Astral and ethereal travel are not difficult, as the systems for encounters and the chance for the hazards of the psychic wind and ether cyclone are but brief sections of APPENDIX C: RANDOM MONSTERS ENCOUNTERS, easily and quickly handled. Other forms of travel, the risks and hazards thereof, you must handle as you see fit. For instance, suppose that you decide that there is a breathable atmosphere that extends from the earth to the moon, and that any winged steed capable of flying fast and far can carry its rider to that orb. Furthermore, once beyond the normal limits of earth's atmosphere, gravity and resistance are such that speed increases dramatically, and the whole journey will take but a few days. You must then decide what will be encountered during the course of the trip – perhaps a few new creatures in addition to the standard ones which you deem likely to be between earth and moon.

That's exactly what I'd have liked to see more of!

Then comes what conditions will be like upon Luna, and what will be found there, why, and so on. Perhaps here is where you place the gateways to yet other worlds. In short, you devise the whole schema just as you did the campaign, beginning from the dungeon and environs outward into the broad world – in this case the universe, and then the multiverse.

This is excellent. I only wish he had teased this out just a little bit more – not to mention produced a fuller example of such a setting.

You need do no more than your participants desire, however. If your players are quite satisfied with the normal campaign setting, with occasional side trips to the Layers of the Abyss or whatever, then there is no need to do more than make sketchy plans for the eventuality that their interests will expand. In short, the planes are there to offer whatever is needed in the campaign. Use them as you will.

I am perhaps greedy (and ungrateful) in wanting a much longer section devoted to this and related topics from the pen of Gygax. It is clear he had ideas for the planes that he was prevented from ever publishing and I would very much like to have seen what he had in mind. If this small section of the Dungeon Masters Guide is any indication, I think his conceptions of the planes would have been quite inspiring and very different from what other authors would produce later.

October 19, 2021

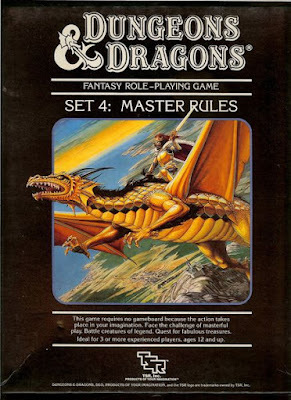

Retrospective: Dungeons & Dragons Master Rules

Over the years I've written this blog, I've been a consistent critic of what I call "kiddie D&D" – my name for the version of the game developed by Frank Mentzer, starting with the 1983 Basic Rules boxed set. Whatever my feelings on the matter, there's no question that this version was immensely successful. According to some reports (and Mentzer's boasts), TSR sold more copies of kiddie Dungeons & Dragons than any other published during the company's existence. I can believe it too, judging by the large number of gamers just a little younger than myself who look on these boxed sets with a great deal of fondness.

Over the years I've written this blog, I've been a consistent critic of what I call "kiddie D&D" – my name for the version of the game developed by Frank Mentzer, starting with the 1983 Basic Rules boxed set. Whatever my feelings on the matter, there's no question that this version was immensely successful. According to some reports (and Mentzer's boasts), TSR sold more copies of kiddie Dungeons & Dragons than any other published during the company's existence. I can believe it too, judging by the large number of gamers just a little younger than myself who look on these boxed sets with a great deal of fondness.

Ultimately, Mentzer's D&D consisted of five boxed sets: Basic, Expert, Companion, Master, and Immortals. I actually think rather highly of the Companion Rules, but the same cannot be said of its immediate follow-up, the Master Rules, first published in 1985. According to the set's introduction, the Master Rules deal with "the ultimate level of might and glory" (levels 26–36). This would seem to mean that characters at this level are akin to mythological heroes who regularly interact with the gods (called "immortals" throughout this set) and will, in fact, one day join their ranks. I don't find this focus particularly compelling, but it's one with which D&D has toyed in the past. Deities & Demigods, for example, addresses this matter briefly and I remember hearing about campaigns in my youth in which player characters achieved godhood.

The boxed set consists of two rulebooks, one for players and one for the Dungeon Master. The Players' Book consists of three main sections. The first deals with character classes, providing rules expansions to handle levels up to 36. This material is absurd in my opinion. The numbers involved in everything, from hit points to saving throws to the combat charts, are such that one wonders whether it's even worth rolling to determine success. More than that, the mechanical acrobatics necessary to make demihuman characters, who reached maximum level all the way back in the Expert Rules, are laughable. That alone makes me question the wisdom of ever producing these rules. The second section introduces "weapon mastery" rules, a complex system of weapon specialization that requires the use of a very complicated table. The third section introduces rules for sieges for use with the "War Machine" mass combat system in the Companion Rules.

The DM's Book likewise has three sections, the first of which details a variety of rules expansions and additions. One of these introduces "mystics," which are a new character class similar to AD&D's monk. It's in this section that we also get an overview of the various paths to immortality available to characters and that will be expanded upon in the next boxed set. The second section is filled with absurdly powerful monsters, while the third focuses on artifacts. There's also a map of the entirety of the "Known World" setting (later dubbed Mystara), which I imagine piqued many gamers' interest at the time, since we'd never seen anything like it prior to this point.

All in all, the Master Rules are a mess. They seem to exist solely to fill in a gap in the progression toward the Immortal Rules rather than being based on a clear thematic need. The Basic Rules, for example, focus on dungeon adventures, while the Expert Rules expand organically from that toward wilderness exploration. From there, we get domain rulership in the Companion Rules, which is a logical progression. But the Master Rules? What do they offer in this progression? Is preparation for godhood the next logical step? Even if it is, the bigger problem is that rules, as presented here, break down, with new real way to challenge characters whose "to hit" rolls and saving throws are so low and whose hit point totals so high. Mind you, I'm not sure anyone ever played campaigns at such high levels, so the whole matter may be academic in the end.

October 18, 2021

White Dwarf: Issue #13

Issue #13 of White Dwarf (June/July 1979) features a cover by Eddie Jones that recalls Robert E. Howard's Conan the Cimmerian (or at least the version of him that graced many a panel van in the '70s). Ian Livingstone's editorial concerns itself with the fact that many readers write in asking him for advice on where to find players for various RPGs. His reply is to make use of the free "Help!" column to locate them. He adds that "gaming as a hobby is still in its infancy," it will take some effort to make contact with others who share one's own interest in it. Again, not living in the UK at the time, I can't speak to the truth of this. I can only say that, six months later, when I would first enter the hobby in the USA, I had no difficulty finding people with whom to play, first in my own neighborhood, then in school, and even farther afield.

Issue #13 of White Dwarf (June/July 1979) features a cover by Eddie Jones that recalls Robert E. Howard's Conan the Cimmerian (or at least the version of him that graced many a panel van in the '70s). Ian Livingstone's editorial concerns itself with the fact that many readers write in asking him for advice on where to find players for various RPGs. His reply is to make use of the free "Help!" column to locate them. He adds that "gaming as a hobby is still in its infancy," it will take some effort to make contact with others who share one's own interest in it. Again, not living in the UK at the time, I can't speak to the truth of this. I can only say that, six months later, when I would first enter the hobby in the USA, I had no difficulty finding people with whom to play, first in my own neighborhood, then in school, and even farther afield.The issue's first article is "Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Combat Tables," a four-page excerpt from the forthcoming Dungeon Masters Guide. I believe Dragon had a similar feature around the same time – proof, I think, that the release of the final volume of AD&D was much anticipated by D&D players, as it would finally provide many much needed tables, charts, and rules to replace those found in OD&D. "The Fiend Factory" also appears in this issue, providing more monsters for use with D&D. Most interesting to me were the collection of elemental monsters called "imps" in this issue, but renamed "mephits" in the pages of the Fiend Folio.

Of very great interest to me was "Expanding Universe" by the excellent Andy Slack. This is the first part of a series of articles intended to, as its title suggests, expand the universe of GDW's Traveller. Slack offers new and supplementary rules for skills and poisons, some of which (like the rules for languages and learning by experience) are quite useful. I fondly remember Andy Slack's contributions to White Dwarf, which were among my favorite parts of the magazine. Seeing the very first installment, which I never saw back in the day, is thus a small thrill for me.

"Open Box" presents only three reviews: the D&D modules In Search of the Unknown and Tomb of Horrors. Since Don Turnbull is the reviewer of these products, he rates them very highly – 9 and 10 respectively – and his criticisms are few (he complains about the use of Roman numerals in module B1, for example). The third review is of the Games Workshop's Dungeon Floor Plans, which would seem to be something akin to Heritage USA's Dungeon Floors. They're a collection of sheets intended to be cut apart and used in conjunction with miniatures to represent the layout of a dungeon. The reviewer likes them very much and gives them a score of 9. Never having seen them myself, I have no basis for agreeing or disagreeing with this assessment.

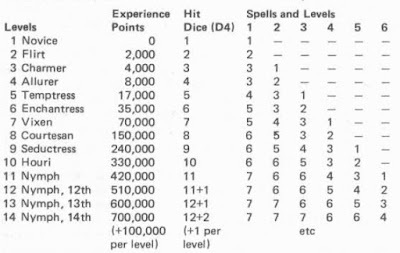

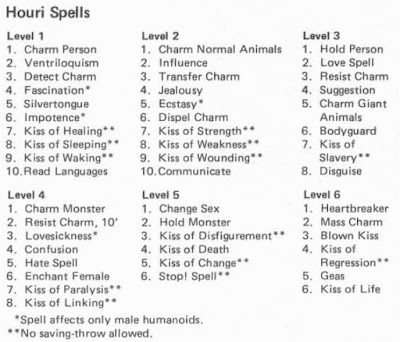

Next up is Brian Asbury's "The Houri Character Class," an alternate female-only magic-user sub-class that relies on charm and seduction. Here's the class's advancement chart, followed by its spell list.

In the interests of space and good taste, I will not reproduce the seduction table here. While I'm not especially fond of … specialized character classes such as this, I can't completely condemn it either. Pulp fantasy is, after all, filled with femmes fatales and enchantresses, so I can understand why some referees might see utility in a class such as this. Even so, the houri isn't an especially interest take on the archetype in my opinion. It's both prurient and puerile, but that's far from unexpected. As I said, I'm not offended by it, simply bored (though the magic items, manual of advanced lovemaking and lipstick of irresistibility, are ridiculous enough that I might be persuaded to change my mind).

In the interests of space and good taste, I will not reproduce the seduction table here. While I'm not especially fond of … specialized character classes such as this, I can't completely condemn it either. Pulp fantasy is, after all, filled with femmes fatales and enchantresses, so I can understand why some referees might see utility in a class such as this. Even so, the houri isn't an especially interest take on the archetype in my opinion. It's both prurient and puerile, but that's far from unexpected. As I said, I'm not offended by it, simply bored (though the magic items, manual of advanced lovemaking and lipstick of irresistibility, are ridiculous enough that I might be persuaded to change my mind).Part six of Rowland Flynn's "Valley of the Four Winds" is here, as is another installment of "Treasure Chest." This time there are fourteen new spells by a variety of authors. One such author is Richard Nixon, which I initially thought a joke, but, reading his contributions – catatonic control, rope control, and spell store – it's clear that he simply had the misfortune of sharing his name with the disgraced US president. Go figure!

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers