James Maliszewski's Blog, page 130

September 10, 2021

Random Roll: FF, p. 3

I will in future return to highlighting choice passages in the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide, but I recently came across a section of the Fiend Folio that I thought worthy of attention. In the foreword to that tome of creatures malevolent and benign, editor Don Turnbull talks about the process of putting together this "companion" to the Monster Manual. In doing so, he makes a number of intriguing statements, starting with the passage where he explicitly compares the FF to its predecesssor.

There is one major difference between the two volumes – the source of their contents. The Monster Manual is very largely the work of one person – Gary Gygax – who not only created and developed most of the Monster Manual monsters himself but also developed those he did not personally create.

Remember, this is 1981, by which point Gary Gygax reigns supreme over all things AD&D and I suspect that Turnbull's statement needs to be considered in that light. Even so, there is nevertheless merit to what he says about the contents of the Monster Manual. One can rightly quibble about how many of the MM's entries were created solely by Gygax. Yet, the larger point remains that Gygax's influence over that first published AD&D book was considerable.

The new monsters in the FIEND FOLIO Tome, however, are the creations of many people. Some time ago, the editor of a UK magazine asked readers to submit their monster creations to a regular feature which became known as the Fiend Factory. The response was quite enormous and many worthwhile contributions reached the editorial offices.

There are several things of note here, starting with the fact that the name of the "UK magazine" referenced above – White Dwarf – is never mentioned. This is despite the fact that the Fiend Factory feature of that periodical is mentioned. Likewise, one assumes, since White Dwarf was never owned by TSR, some sort of financial and legal arrangement had to be arranged whereby some of the content of the Fiend Factory feature would appear in this book. I wonder if the establishment of TSR UK played a role in the circuitous way that Turnbull speaks here (Games Workshop, publisher of White Dwarf, having previously been the distributor of TSR products in the UK).

Also notable is the fact that, while the text bolds the titles of TSR game book (and, in the case of the Fiend Folio, capitalizes them as well), there are none of the ubiquitous trademark or registered trademark symbols that started to appear in 1980. In any case, Turnbull continues:

As editor of the feature, I never lacked for new and interesting monsters to fill the Factory pages each issue – indeed (for a magazine has inevitable limitations on space) it very soon became evident that many worthwhile creations would not be published until long, long after their submission, if at all. At the same time, the readers were praising the feature and demanding more! So there was a goodly supply of, and strident demand for, additional AD&D monsters – and these two factors gave birth to the FIEND FOLIO Tome of Creatures Malevolent and Benign.

This volume therefore contains an overwhelming majority of monsters which were originally submitted for the Fiend Factory feature. A small fraction of them already appeared in the Factory (though not in as developed a form as they appear here) while a larger number have come straight from creation via development to this book without pausing at the Factory en route.

The second paragraph is very interesting to me. It's regularly stated that the Fiend Folio is largely a compilation of Fiend Factory monsters. If I'm reading Turnbull correctly, he's saying that many of them never appeared in the pages of White Dwarf at all and that he drew upon his large "slush pile" of submissions for many of the monsters that appear in the FF.

Later in the foreword, Turnbull talks about his own role in producing the book.

My own task has been quite a simple one – to select monsters for inclusion, to develop them as necessary and write the statistics and texts, to assemble them in coherent form and to produce the various tables. Perhaps selection was not so easy a task after all, for there were over 1,000 contributions to consider; I have been quite ruthless in selection to ensure that the monsters which finally did appear were of the highest quality and originality.

"Over 1,000 contributions?!" That's considerably more than I would have expected.

To have sacrificed quantity for quality in this way is, I believe, what discerning AD&D enthusiasts would want me to have done. On the development side my efforts have been variable. Some "originals" were almost fully developed when they reached me and not a great deal of work was required to add the final touches to them. At the opposite end of the development spectrum, other contributions arrived incomplete and embryonic, with the tip of a good idea just showing above the surface, as it were; these needed development to "flesh them out" into complete and coherent form. A few names have been changed and a few characteristics altered (most for good and sufficient reasons, some out of sheer instinct) but substantially the task has been to build on creations rather than re-work them entirely.

Had I greater love for the Fiend Folio's monsters, I might take the time and compare their original appearances in the Fiend Factory feature to the versions that later appeared in the AD&D book. I may still do that, as part of my ongoing examination of the early issues of White Dwarf, but, if so, it will be in a haphazard fashion. Regardless, I think Turnbull's admission of the extent to which he was involved in the development of the book's monster entries is important. It's a pity he's been dead for nearly two decades, as I'd love to talk to him about the nitty gritty details of his shepherding the Fiend Folio to its final form. I suspect he'd have a few additional surprises to share with us regarding both the process and the extent of his own creative contributions.

September 8, 2021

Retrospective: War of Wizards

Reading issue #8 of White Dwarf in preparation for this week's post, I was reminded of the existence of War of Wizards, published by TSR in 1975. Appearing in May 1975, the game is fascinating on a number of levels, starting with the fact that, because of its publication date, it's the first appearance of the world of Tékumel in print. Remember that Empire of the Petal Throne, which is usually taken to be the world's introduction to the setting, wouldn't appear for another few months and understandably so. EPT is a full-fledged roleplaying game, featuring a 114-page rulebook and multiple maps, while War of Wizards is simply a "game of fantastic duels between mighty sorcerers." In terms of content, depth, and presentation, there's not much commonality between the two – and, yet, it's precisely for that reason that I think War of Wizards is worthy of discussion.

Reading issue #8 of White Dwarf in preparation for this week's post, I was reminded of the existence of War of Wizards, published by TSR in 1975. Appearing in May 1975, the game is fascinating on a number of levels, starting with the fact that, because of its publication date, it's the first appearance of the world of Tékumel in print. Remember that Empire of the Petal Throne, which is usually taken to be the world's introduction to the setting, wouldn't appear for another few months and understandably so. EPT is a full-fledged roleplaying game, featuring a 114-page rulebook and multiple maps, while War of Wizards is simply a "game of fantastic duels between mighty sorcerers." In terms of content, depth, and presentation, there's not much commonality between the two – and, yet, it's precisely for that reason that I think War of Wizards is worthy of discussion.Before getting into the specifics of the game itself, I want to devote a little time to its presentation of Tékumel. As most readers probably already know, M.A.R. Barker first began work on the earliest version of Tékumel when he was still a child. Upon that foundation, he then further developed the setting in multiple phases, from the 1940s till the time when was introduced to Dungeons & Dragons in 1974. I say "versions," because, during each phase of development, Barker's conception of Tékumel changed, sometimes in small ways and sometimes in big ones. An example of a big change, for example, is the use of the terms "good" and "evil" to describe deities who would later be associated with "stability" and "change," respectively. In War of Wizards, though, we see neither of these formulations. Instead, Barker calls the gods the "Lords of Glory" and the "Rulers of Shadow." Purely from a historical perspective, this is interesting to me, as it suggests the degree to which the setting was still in flux within Barker's mind. Rather than emerging fully formed, like Athena from the head of Zeus, Tékumel grew over time and through play (as all good RPG settings do).

War of Wizards is a two-player game that models a trial by combat between two spellcasters, whether as part of a match in one of the Hirilákte arenas found in most large Tsolyáni cities or as part of a more personal duel. Regardless of the ostensible reason, each player can choose to play either a priest or a sorcerer. The former may wear armor, while the latter have access to a wider array of offensive spells. These combatants are characters each possessing three ability scores rated from 2–200 (achieved by rolling percentile dice twice). The first of these, Physical Strength, functions primarily like hit points. The other two, Attack and Defense Strength, represent pools of points that can be used to power spells. Each spell in the game has a cost and characters can continue to cast spells so long as they have enough points in the appropriate ability score. In a pinch, it's possible to shift points from Physical Strength to the other two scores, but doing so weakens the character, making it easier for his opponent to defeat him.

The game was released in two versions: the first was unboxed and the second boxed. The boxed version included four metal miniatures, supplementing the cardboard counters that are included in both versions. Integral to play is a "board" consisting of 20 spaces that abstractly handle the distance between the two combatants and their spell effects. The board is quite attractive, since it features artwork by Barker along its edges. Here's an example of one section of the board:

I only acquired a copy of War of Wizards fairly recently, so I've never had the chance to play it. Reading through the rules, it doesn't seem like it would be difficult to learn, though there does seem to be a lot of bookkeeping involved. Keeping track of all the points spent and lost, for example, might well be tedious – a common problem in "spell point" magic systems in my opinion – though, with time and practice, it might become less so. Even so, I find this game very intriguing, if only for its presentation of another version of Tékumel, one that's a little simpler and less exotic than that in later versions and yet still much more flavorful and different than the commonplace "vanilla" settings that dominated the hobby then and now.

I only acquired a copy of War of Wizards fairly recently, so I've never had the chance to play it. Reading through the rules, it doesn't seem like it would be difficult to learn, though there does seem to be a lot of bookkeeping involved. Keeping track of all the points spent and lost, for example, might well be tedious – a common problem in "spell point" magic systems in my opinion – though, with time and practice, it might become less so. Even so, I find this game very intriguing, if only for its presentation of another version of Tékumel, one that's a little simpler and less exotic than that in later versions and yet still much more flavorful and different than the commonplace "vanilla" settings that dominated the hobby then and now.

September 7, 2021

Down in the Dungeon Auction

Some time ago, I wrote a post about a 1981 art book entitled Down in the Dungeon. A childhood friend's older brother, who was one of my gaming mentors, owned a copy of the book and we often sat staring at its weird and wonderful illustrations by Don Greer.

Some time ago, I wrote a post about a 1981 art book entitled Down in the Dungeon. A childhood friend's older brother, who was one of my gaming mentors, owned a copy of the book and we often sat staring at its weird and wonderful illustrations by Don Greer. I recently learned that many of the original paintings are being auctioned online, starting September 13, 2021. I know there are a few collectors of gaming art who read this blog, so I thought I'd share this news here. Likewise, please feel free to spread the word elsewhere, as I'm sure the auction will be of interest to others as well. Had I the resources to do so, I might consider snagging one of these myself. "No Exit" is a particularly appealing piece and I'd love to learn that it's getting a good home.

September 6, 2021

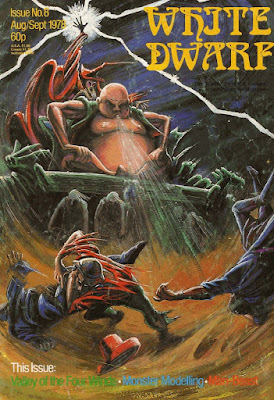

White Dwarf: Issue #8

Issue #8 of White Dwarf (August/September 1978) features a very striking cover by Derek Hayes. The story depicts a scene from Rowland Flynn's short story, "The Valley of the Four Winds," which appears later in the same issue (about which more shortly). Ian Livingstone's editorial returns to two common subjects of his pieces: first, that the USA produces more games than does the UK and, second, that "traditionalists" are slow to accept that "the presence of monsters and magic does not mean the absence of skill in play." If nothing else, these editorials offer one perspective on the British gaming scene in the late '70s, a perspective of which I might otherwise not be aware.

Issue #8 of White Dwarf (August/September 1978) features a very striking cover by Derek Hayes. The story depicts a scene from Rowland Flynn's short story, "The Valley of the Four Winds," which appears later in the same issue (about which more shortly). Ian Livingstone's editorial returns to two common subjects of his pieces: first, that the USA produces more games than does the UK and, second, that "traditionalists" are slow to accept that "the presence of monsters and magic does not mean the absence of skill in play." If nothing else, these editorials offer one perspective on the British gaming scene in the late '70s, a perspective of which I might otherwise not be aware."Monster Modelling" by Mervyn Lemon is a wonderfully practical short article, in which the author provides four examples of how to turn wire, tissue paper, and other bits of household materials into miniature figures. The article includes fairly detailed diagrams on how Lemon created the monsters, much to my pleasure. Being utterly lacking in handicrafts, this is a subject that fascinates me. The "Fiend Factory" returns with eight more monsters for use with Dungeons & Dragons, including the tween, the carbuncle, and the coffer corpse, all of which would later be reprinted in the Fiend Folio.

Lewis Pulsipher offers up "Critical Hits," which is a relatively simple system for handling, in his words, "the odd chances of combat." Interestingly, Pulsipher's approach requires first a natural roll of 20 followed by a second roll that must be high enough to hit the target's armor class. This is similar to the approach adopted in Third Edition D&D and makes critical hits rarer than the 5% chance found in many other systems from the same era. If a critical hit is indicated, there's a d20 roll on a table to determine the effect, with double damage occurring only on rolls of 17–20 (all other rolls indicate some sort of temporary impairment, such as the shield arm becoming useless or unconsciousness). All things considered, it's not a bad system.

Part IV of Brian Asbury's eponymous "Asbury System" – the last part, he explains – focuses on percentile abilities, such as those employed by thieves and bards. Each success in using these abilities grants experience points, with diminishing returns. As I have said before, while I genuinely appreciate what Asbury is attempting to do with his system, I'm not sure the added complexity and bookkeeping justifies its use. "The Man-Beast" by Greg Foster is a new character class for D&D, representing a character who, through the use of a magic ring, can transform between being, well, a man or a beast. The class is thus similar to being a lycanthrope and is intended primarily for characters "with a tendency towards evil." I'm honestly a bit baffled by it, but I nevertheless enjoy seeing weird experiments like this one. They're a good reminder of the reckless inventiveness that the early hobby encouraged.

"Open Box" includes reviews of FGU's Space Marines miniatures rules, Starships & Spacemen, TSR's Monster Manual, and War of Wizards. All these products get good reviews, with the Monster Manual receiving the most effusive praise. Meanwhile, the "Letters" page contains four missives from readers and previous authors responding to comments and criticisms. The most interesting of these is Roger Musson's reply to Gary Gygax's intemperate letter in issue #7. By and large, Musson takes Gygax's criticisms in good spirit, which is to his credit. At the end of his reply, he nevertheless cannot resist – and I do not blame him – calling out Gygax's hyperbole:

Well said.

Well said.David Lloyd's "Kalgar" comic continues, followed by part one of the aforementioned short story by Rowland Flynn, "The Valley of the Four Winds." When I saw the title, I initially thought of the adventure scenario for FGU's Bushido , which has the same name. Instead, it appears to relate to a collection of figures produced by Miniatures Figurines Ltd. of Southampton. An advertisement depicting the figures appears on the page immediately after the short story.

This issue felt strangely light by comparison to previous ones, even though it's the same length (28 pages) as its immediate predecessors. Perhaps it's my imagination, but there appeared to be more advertisements, several of them full-page in size, in this issue than there had been previously. True or not, issue #8 is not a stand-out one for me. If anything, it's yet another reminder of just how difficult it has always been to produce consistent quality in a periodical. With even my minimal experience in this area, I have great sympathy for what Ian Livingstone and his crew were doing, which is why I find it difficult to offer much criticism when an issue does not fully seize my attention. On to issue #9!

This issue felt strangely light by comparison to previous ones, even though it's the same length (28 pages) as its immediate predecessors. Perhaps it's my imagination, but there appeared to be more advertisements, several of them full-page in size, in this issue than there had been previously. True or not, issue #8 is not a stand-out one for me. If anything, it's yet another reminder of just how difficult it has always been to produce consistent quality in a periodical. With even my minimal experience in this area, I have great sympathy for what Ian Livingstone and his crew were doing, which is why I find it difficult to offer much criticism when an issue does not fully seize my attention. On to issue #9!

September 4, 2021

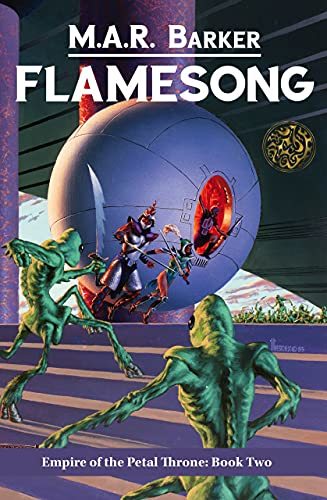

Flamesong Returns

M.A.R. Barker's second novel of Tékumel,

Flamesong

, is available once again, in both paperback and Kindle formats. Of the two Tékumel novels originally published by DAW in the 1980s, Flamesong is by far the more accessible to readers familiar with "traditional" fantasy adventure tales, making it a good entry point for newcomers to the setting. The Tékumel Foundation very kindly asked me to write the foreword to this re-release, which I was happy to do. If all goes well, we'll see new releases of Professor Barker's other three Tékumel novels in the near future.

M.A.R. Barker's second novel of Tékumel,

Flamesong

, is available once again, in both paperback and Kindle formats. Of the two Tékumel novels originally published by DAW in the 1980s, Flamesong is by far the more accessible to readers familiar with "traditional" fantasy adventure tales, making it a good entry point for newcomers to the setting. The Tékumel Foundation very kindly asked me to write the foreword to this re-release, which I was happy to do. If all goes well, we'll see new releases of Professor Barker's other three Tékumel novels in the near future. September 2, 2021

Random Roll: DDG, p. 11

In a change of pace, I thought it might be interesting to take a look at a section from AD&D's Deities & Deimgods. On page 11 of that book, there's a section entitled "Divine Ascension," which I recall attracted a lot of attention among players I knew in my youth.

As study of the various mythologies will show, it is remotely possible for mortals to ascend into the ranks of the divine. However, there are certain requirements that must be fulfilled before such a thing could happen.

While I suppose it's possible that the players interested in seeing their characters ascend to godhood did so in imitation of Greco-Roman style apotheosis, I suspect the vast majority of them did so for far less historically-grounded reasons.

First, the character in question must have advanced to an experience level that is significantly above and beyond the average level of adventure-type characters in the general campaign. (This includes all such non-player types as military leaders, royal magic-users, etc.) For example, if the average level of characters in a campaign, both player and non-player, is around 5th level, then a candidate for ascension should be something like 9th or 10th level. If the average level is something like 15th level, then a character would have to be in the realm of 25th–30th level!

Given the overall premise – divine ascension – this seems reasonable. The fact that it specifies level ranges is surprisingly practical. That those levels are scaled to the average level of the campaign is fascinating.

Second, his or her ability scores must have been raised through some world-shaking magic to be on par with the lesser demigods. (Should such an act be lightly considered, remember that a wish spell is the most powerful magic that mankind can control, and such an average increase in abilities would literally take the power of dozens of wishes! Each use of that spell weakens the caster and ages him 3 years into the bargain, so they are not easy to come by.)

A quick perusal of the demigods described in the DDG suggests that even the "lesser" ones have multiple – if not all – ability scores above 18, usually in the 20–22 range Given that, this second requirement is particularly onerous and, in any reasonably run AD&D campaign, probably completely out of reach of most player characters.

Third, the personage must have a body of sincere worshipers, people convinced of his or her divinity die to their witnessing of and/or belief in the mighty deeds and miracles which he or she has performed (and continues to perform). These must be genuine worshipers, honest in their adoration or propitiation of the person.

Again, this seems reasonable, though, in a world in which magic is, if not commonplace, a well-established and widely known thing, what constitutes a "miracle?" "Mighty deeds" are probably easier to quantify, though these too are probably defined in a relative fashion.

Fourth, the person in question must be and have been a faithful and true follower of his or her alignment and patron deity. It is certain that any deviation will have been noted by the divine powers.

The most notable thing about this last requirement is the implication that being "a faithful and true follower" of one's alignment is not the same thing as being such of one's patron deity. The relationship between alignment, the Outer Planes, and the gods in AD&D is a vast topic with no clear answers, so I won't delve into it here. However, I do want to draw attention to it, since I think there are some rich possibilities to mine.

If all of the above conditions have been met, and the character has fulfilled a sufficient number of divine quests, then the character's deity may choose to invest the person with a certain amount of divine power, and bring the character into the ranks of the god's celestial (or infernal) servants.

"Divine quests?" Are these the same as the mighty deeds and miracles mentioned earlier or something else entirely? I assume the latter, though the text is not clear.

This process of ascension usually involves a great glowing beam of light and celestial fanfare, or (in the case of transmigrating to the lower planes), a blotting of the sun, thunder and lightning, and the disappearance of the character in a great smoky explosion.

Perhaps it's just me, but I find the description of ascension rather tacky.

Characters thus taken into the realms of the gods will serve their patron as minor functionaries and messengers. After several centuries of superior service and gradual advancement, exceptional servants may be awarded the status of demigod, which includes have an earthly priesthood and the ability to grant spells (up to 5th level) to the demigod's clerics.

The bit about demigods being able to grant spells of up to 5th level is an interesting expansion/clarification of a section in the Dungeon Masters Guide that talks about the acquisition of clerical spells.

Naturally, ascension to divinity effectively removes the character from the general campaign, as the person will become a non-player member of the DM's pantheon.

I think this final sentence pretty well sums up the general tenor of this section: yes, it's possible for a character to ascend to godhood, but it's really hard to do and, in the end, your character becomes an NPC who might, in a few centuries be recognized by mortals for his divinity. In short: why bother?

September 1, 2021

Grognard's Grimoire: Teteku

Teteku (Scaled Strider)

Standing between 6 and 8 feet tall at the shoulder, teteku are reptilian creatures with long, slender necks and gracile heads. These creatures walk on two muscular hind limbs, forelimbs being mostly useless outside of mating displays. Wild teteku roam in herds across all five continents of sha-Arthan, while domesticated breeds have played important roles in most societies, both human and non-human, since at least the First Cycle, if not longer.

Riding TetekuBred for swiftness, these teteku can survive on a purely vegetarian diet, such as krutha-grass or ulevanma-weeds.

AC 6 [13], HD 2 (9hp), Att1 × bite (1d6), THAC0 18 [+1], MV 240’ (80’), SV D12 V13 P14 B15 S16 (1), ML 7, XP20, NA 0 (0), TT None

Beast of burden: Carry up to 40 STR worth of items unencumbered; up to 70 STR at half speed.Domesticated: Not encountered in the wild.War TetekuBred for strength and ferocity in battle, these teteku are adapted for short bursts of speed rather than long-distance riding. Some breeds of war teteku, such as the Ga’andrin yanenka, are carnivorous, but most retain herbivorous ways.

AC 6 [13], HD3(13hp), Att1 × bite (1d8), THAC0 17[+2], MV 120’ (40’), SV D12 V13 P14 B15 S16 (2), ML 9, XP35, NA 0 (0), TT None

Beast of burden: Carry up to 35 STR worth of items unencumbered; up to 70 STR at half speed.Charge: When not in melee. Requires a clear run of at least 20 yards. Rider’s lance inflicts double damage. Teteku cannot attack when charging.Domesticated: Not encountered in the wild.Melee: When in melee, both rider and teteku can attack.Wild TetekuAdapted to run at high speed, these teteku still exist in large numbers on the continents of Alakun-Tenu and Beyash (and in smaller numbers elsewhere).

AC 6 [13], HD 2 (9hp), Att1 × bite (1d4), THAC0 18 [+1], MV 240’ (80’), SV D12 V13 P14 B15 S16 (1), ML 7, XP20, NA 0 (1d10 × 10), TT None

Stampede: Herds of 20 or more can trample those in their path. 3-in-4 chance each round. +4 to human-sized or smaller creatures. 1D20 damage.Taming: Wild teteku can be trained as mounts (riding teteku).My Precious

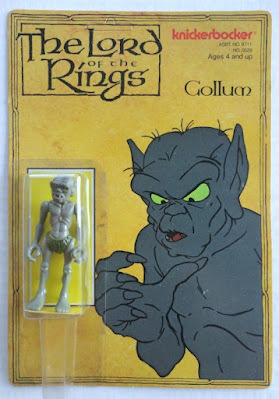

Ralph Bakshi's 1978 animated film, The Lord of the Rings, is a strange beast. That's understandable, given the immense undertaking of adapting such a complex novel. From what I gather, the film was financially successful and Bakshi fully intended to make a second part to conclude the story, but, for a variety of reasons, United Artists decided against going ahead with it. Instead, fans had to make do with the 1980 Rankin/Bass TV movie The Return of the King (which is itself a very strange thing, though for very different reasons).Despite this, there's plenty of evidence that either Bakshi or UA initially had high hopes for The Lord of the Rings. I make this assertion because there was a surprisingly large amount of merchandise released to promote it, including a line of action figures from Knickerbocker Toys.

Ralph Bakshi's 1978 animated film, The Lord of the Rings, is a strange beast. That's understandable, given the immense undertaking of adapting such a complex novel. From what I gather, the film was financially successful and Bakshi fully intended to make a second part to conclude the story, but, for a variety of reasons, United Artists decided against going ahead with it. Instead, fans had to make do with the 1980 Rankin/Bass TV movie The Return of the King (which is itself a very strange thing, though for very different reasons).Despite this, there's plenty of evidence that either Bakshi or UA initially had high hopes for The Lord of the Rings. I make this assertion because there was a surprisingly large amount of merchandise released to promote it, including a line of action figures from Knickerbocker Toys. I didn't see the movie until sometime in the mid-1980s, after it had been released on VHS. However, I came across the figures – or, rather, one of them – while on vacation in the summer of 1979. This was a few months before I'd encounter D&D for the first time and before I'd even read Tolkien's works. The figure in question is the one pictured above – Gollum. Now, by this point, I had seen the 1977 Rankin/Bass TV movie version of The Hobbit, but I don't think I connected it to The Lord of the Rings. Even assuming I had, I was still baffled by the figure, as he looked nothing like the way Gollum was portrayed by Rankin/Bass (not that I'm defending that portrayal, mind you). Still, there was something intriguing about this emaciated little hunk of plastic and I bought it (very inexpensively, since the store where I found it sold lots of remaindered items at steep discounts). I thought about the Gollum figure the other day while I was doing some cleaning and came across a few other mementos of my childhood. I no longer own the Gollum figure – Crom knows what became of it – but thinking of it briefly transported me back to the very end of the 1970s, in the final days of my pre-Dungeons & Dragons innocence, when "fantasy" was a chaotic, undifferentiated mass of weird stuff without any clear explanation or context. Looking back, it was a heady time for my imagination and I'd give a lot to be able to revisit it, if only for a brief time.

Remembering Norman Bean

On this day in 1875, Edgar Rice Burroughs was born in Chicago, Illinois. Much like H.P. Lovecraft, whose birthday was less than two weeks ago, Burroughs is one of the oft-forgotten founders of contemporary fantasy and science fiction. His tales of John Carter of Mars, in particular, have exercised an enormous influence on subsequent portrayals not only of the Red Planet but of interplanetary adventure more generally. Carter and the abilities he possesses while on Barsoom was one of the models for the creation of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster's Superman. And, as I never tire of telling anyone will listen, Barsoom was also a key inspiration for the creation of Dungeons & Dragons. Between Superman and D&D, there can be little question that the lasting impact of Burroughs's stories and ideas on contemporary popular culture is immense – not a bad legacy!

Many later creators have expressed their admiration for Burroughs and the debt they owed to him, starting with Ray Bradbury, himself the author of many influential stories, who once said that "Burroughs … probably changed more destinies than any other writer in American history." George Lucas claimed that "my entire world changed when I was given the Warlord of Mars at the age of 8. I got onto Edgar Rice Burroughs … and the curtain went up. . . There was the universe and stars and comets and what-not, and I was never the same afterwards.” Lucas was far from the only one to feel that way and we have the imagination of Edgar Rice Burroughs to thank for that.

August 31, 2021

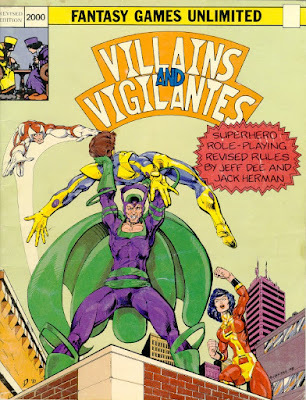

Retrospective: Villains and Vigilantes

II've never been a huge fan of superheroes. As a kid, I liked them well enough, but my interest in them paled in comparison to fantasy or (especially) science fiction. This was true even of the few comics I read in my youth (like Marvel's The Micronauts – don't judge me). Consequently, once I got into roleplaying games, I was in no hurry to seek out superhero RPGs and, in fact, didn't play one until 1982. Even then, my interest was fleeting and limited, which is why I don't think I was all that aware of the existence of any games in this genre beyond Champions.

II've never been a huge fan of superheroes. As a kid, I liked them well enough, but my interest in them paled in comparison to fantasy or (especially) science fiction. This was true even of the few comics I read in my youth (like Marvel's The Micronauts – don't judge me). Consequently, once I got into roleplaying games, I was in no hurry to seek out superhero RPGs and, in fact, didn't play one until 1982. Even then, my interest was fleeting and limited, which is why I don't think I was all that aware of the existence of any games in this genre beyond Champions.

That's not entirely true. I was aware of the existence of Villains and Vigilantes, thanks to a series of interesting advertisements in the pages of Dragon. If I remember correctly, the ads features full character write-ups, complete with game stats and a portrait by Jeff Dee, whose art I knew well from D&D. Intriguing though they were, I never sought out V&V nor did I ever meet anyone else who played it. I don't believe I ever laid eyes on the game until sometime in the 1990s/

That's a shame, because Villains and Vigilantes is not only the second superhero RPG ever published (the first being Superhero 2044) but also includes a number of unique features that set it apart from other games in the same genre. Written by Jeff Dee and Jack Herman and first published by Fantasy Games Unlimited in 1979, V&V clearly owes a lot to Dungeons & Dragons. For example, V&V uses the full set of polyhedral dice, has levels, alignment (Good and Evil), and basic characteristics rated between 3 and 18. In addition, like Gamma World's mutations, super powers are determined by means of a series of random rolls rather than player choice.

Most significantly, the basic assumption of V&V is that the characters are "duplicates of the players themselves with the addition of superpowers." The game goes on to say, "It has been our experience that playing oneself in V & V is definitely more enjoyable than creating an entirely random character." That's right: in Villains and Vigilantes, you play yourself as a superhero. How's that for a premise? Of course, reading that right after I'd noted that super powers are determined randomly no doubt makes one wonder what is meant by "an entirely random character." This is another way in which V&V differs from other superhero RPGs. Remember that basic characteristics are rated between 3 and 18? Those ratings are not randomly rolled. Instead, each player gives himself a rating based his own estimation of his abilities. Furthermore, the rules counsel the GM to "allow players the benefit of the doubt" when it comes to making these judgments, though it also notes that very high and very low scores are "extremely rare."

Though there are levels, there are no character classes. Instead, each level represents an experience point threshold – starting at 2000 and increasing roughly geometrically thereafter – that grants the player a choice of ways for his character to improve, generally in the form of bonuses to characteristics and combat skills. All characters also gain points in Charisma with level, representing growing fame and recognition. V&V doesn't include any clear means of gaining new powers or improving those one already possesses, which is generally fine by me, as it's pretty uncommon for superheroes to change significantly in that respect over time. Combat is, at base, fairly straightforward, consisting of a roll against a target number to succeed. However, that target number of determined by recourse to a chart that cross-references attack and defense powers and then modified in many ways. Ultimately, it's no harder than D&D combat, but it's got many more modifiers to consider.

Villains and Vigilantes is very much an old school RPG in that it doesn't include extensive rules for most situations, instead offering only advice and trusting the GM to demonstrate good judgment. I personally have no problem with this, but I am sure it won't be satisfying to me many people, especially those more accustomed to games like Champions. Indeed, I'd say that the biggest way that V&V differs from most other superhero RPGs is that it's not "effects based" in terms of powers, which is to say, powers are not easily customizable to taste. I think this, more than any of its other peculiarities, probably hampered the popularity of the game, especially after the release of Champions. Ironically, I see this as a plus rather than a drawback, but then I generally prefer much simpler systems for any genre.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers