James Maliszewski's Blog, page 126

November 11, 2021

Random Roll: PHB, p. 32.

A close reading of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rulebooks often reveals little details that are easy to overlook. In most cases, these details are rules-related, but one occasionally finds details that pertain to the implied setting of the game. I came across one of these just recently while re-reading the description of the monk class found in the Players Handbook.

There can be only a limited number of monks above 7th level (Superior Master). There are three 8th level (Master of Dragons) and but one of each higher level. When a player character monk gain sufficient experience points to qualify him or her for 8th level, the commensurate abilities attained are only temporary.

The above is, I think, well known and has been an aspect of the class since its first appearance in the pages of OD&D's Supplement II. Like the druid, the monk is a class that advances to higher levels only through the defeat of the current holder of that level in a trial by combat. I know that, even back in the early days, some players and referees disliked this aspect of the class, both because of its seeming unfairness – why don't other classes have to do this? – and because it introduced an additional layer of complexity to leveling up. For myself, I liked it precisely because it was unique; it gave the monk a bit of flavor to distinguish it further from other classes.

The next sentence of this section of the PHB also contains a bit of flavor, but one that I must have somehow overlooked, because I honestly cannot recall ever reading it before.

The monk must find and defeat in single combat, hand-to-hand, without weapons or magic items, one of the 8th level monks – the White, the Green, or the Red.

For a moment, the colors baffled me. I quickly realized that they were connected to the fact that the title of 8th-level monks is "Master of Dragons," of which there are only three. Thus, it would seem that these monks consist of the Master of White Dragons, the Master of Green Dragons, and the Master of Red Dragons. How had I never seen this detail before? It's baffling to me and yet I have no recollection of ever having seen it, let alone making any use of it in all the years I played AD&D.

The detail makes a certain amount of sense, since, unlike levels above 8th, there are three 8th-level monks, so there ought to be some way to distinguish them. Of course, I soon find myself wondering: Why only three? Why not one for each color of dragon? Is there some special significance to the three dragon colors chosen? Why are they only evil dragons? Thinking about and potentially answering these questions are the stuff from which a fantasy setting is made. I have no idea if Gary Gygax intended there to be a logic behind the three Masters of Dragons or not, but I enjoy puzzling out matters like this regardless. I doubt I'm alone in this regard.

Strange Fascinations

Swiped from Wayne's BooksLike anyone who's been involved in this hobby for decades, I own a lot of roleplaying games, the vast majority of which I don't play regularly. That's inevitable, as there are only so many free hours in a week. Moreover, I still hold out hope that, one day, I'll get the opportunity to gather round the table (real or virtual) and play Gangbusters or Stormbringer again.

Swiped from Wayne's BooksLike anyone who's been involved in this hobby for decades, I own a lot of roleplaying games, the vast majority of which I don't play regularly. That's inevitable, as there are only so many free hours in a week. Moreover, I still hold out hope that, one day, I'll get the opportunity to gather round the table (real or virtual) and play Gangbusters or Stormbringer again. On the other hand, my library of RPGs also includes a few games I've never really played. These are games I bought once upon a time either because I hoped I'd play them or their subject matter simply piqued my interest. I say "a few" such games, because, as a general rule, I try to limit my library to games I have played or are currently playing. I'm not a collector and, in fact, make an effort to prevent myself from developing that sort of mentality toward my games (not that I always succeed).

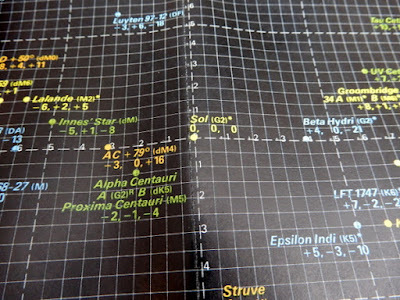

Yet, as I said, I do own games I've never played. SPI's Universe is a good example of what I'm talking about – perhaps the best example of it in my library. I first encountered Universe in 1982, in the Ballantine paperback edition of the game, which I borrowed repeatedly from my local public library. I think what first attracted me to the game is its fold-out "interstellar display," which is basically a map of star systems within a 30 light year globe around Earth. I can't even begin to tell you how appealing that map was to me; I spent many hours simply staring at it and imagining. This was heady stuff to a 13 year-old.

But I never really succeeded in playing Universe, despite the fact that I wanted to. Nevertheless, a copy of the game sits on my shelf next to my desk, alongside Hawkmoon, Bushido, and a handful of other RPGs for which I retain a strange fascination even though I've never played them. I suspect I'm not alone in behaving like this. In fact, I'd love to hear from readers about the roleplaying games they still hold on to, despite the fact that they've never played them.

November 10, 2021

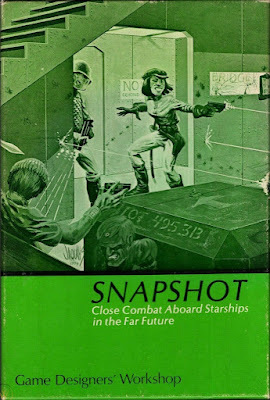

Retrospective: Snapshot

I've never made any secret of the fact that Traveller is without question my favorite roleplaying game. In large part, that's due to my lifelong love of science fiction – some of my earliest memories are watching Star Trek reruns with my aunt in the early 1970s – but I firmly believe that my affection is also due to the elegance of the game's design. Traveller's rules are straightforward, wide-ranging, and expandable. Time and again, GDW showed how relatively easy it was to add to, subtract from, and modify Traveller for various purposes.

I've never made any secret of the fact that Traveller is without question my favorite roleplaying game. In large part, that's due to my lifelong love of science fiction – some of my earliest memories are watching Star Trek reruns with my aunt in the early 1970s – but I firmly believe that my affection is also due to the elegance of the game's design. Traveller's rules are straightforward, wide-ranging, and expandable. Time and again, GDW showed how relatively easy it was to add to, subtract from, and modify Traveller for various purposes.A good example of what I'm talking about is evident in the various boardgames derived from Traveller that GDW published, such as Snapshot. Snapshot first appeared in 1979 in a black and green box of similar size to the 1977 Traveller set. A second edition released in 1983 came in a larger, 8½" × 11" box. I owned the second version and, like so many RPG products of that era, I played it until the box literally fell apart.

Snapshot is an adaptation of Traveller's combat rules for the purposes of simulating, as its subtitle proclaims, "close combat aboard starships in the far future." Inside the box is a 28-page rulebook, a collection of counters, and a sheet featuring the deckplans of a Type-S scout vessel and a Type-A free trader (scaled for use with either the included counters or 15mm miniatures). If you're already familiar with Traveller's combat system, Snapshot is easy to understand. Newcomers might find it takes a little effort to comprehend, but not much. Compared to most miniatures wargaming rules, Snapshot is refreshingly simple.

Make no mistake: that's what Snapshot is – a set of science fiction miniatures wargaming rules. Like other wargames of this kind, it's played in conjunction with scenarios, several samples of which are included in the rulebook. For example, one scenario deals with alien animals destined for an imperial zoological park that get loose while in transit; another deals with an attempted hijacking of a starship. All of the scenarios include victory conditions for one side or the other, as well as options for altering their basic parameters. Of course, referees and players of Traveller would likely have no trouble coming up with scenarios of their own.

Snapshot would seem to have had two audiences in mind. The first is people just looking to play a quick miniatures game and who might, through playing the game, become interested in Traveller. The second is people like myself, who already played Traveller and were keen to get our hands on counters and appropriately scaled maps for use with our RPG adventures and campaigns. It was in that capacity that my boxed set fell apart. Over the course of several years, I made regular use of Snapshot to adjudicate hijackings, boarding actions, and many other combats in and around starships. I can't begin to tell you how many hours my friends and I spent doing this, but it was a lot. I suppose any kid who thrilled upon seeing the opening scene of Star Wars would have a natural affinity for this kind of thing.

A few years ago, when I was refereeing my Riphaeus Sector Traveller campaign, I regretted that we were playing online, because I was keen to pull out my old Snapshot maps and counters whenever the characters became involved in combat aboard a starship. We made do with virtual tools that allowed us to do the same thing, more or less, but I can't deny it didn't quite feel the same to me. They say nostalgia is a hell of a drug and perhaps that's so. On the other hand, the fact that a little box containing cardboard squares and a fold-out map still exercise a hold over my imagination decades later has got to be worth something too.

November 9, 2021

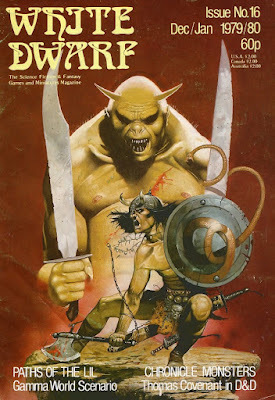

White Dwarf: Issue #16

Issue #16 of White Dwarf (December/January 1979/1980) features a remarkable cover by Les Edwards. Edwards did a lot of cover illustrations for Games Workshop over the years, as well as providing them for the Fighting Fantasy series. That's probably why this issue gives off such powerful vibes for me, even though I never owned it at the time of its original release. It also helps that the issue's contents are excellent, as I'll discuss presently.

Issue #16 of White Dwarf (December/January 1979/1980) features a remarkable cover by Les Edwards. Edwards did a lot of cover illustrations for Games Workshop over the years, as well as providing them for the Fighting Fantasy series. That's probably why this issue gives off such powerful vibes for me, even though I never owned it at the time of its original release. It also helps that the issue's contents are excellent, as I'll discuss presently."Chronicle Monsters" by Lewis Pulsipher is a collection of monsters for D&D derived from Stephen Donaldson's "Chronicles of Thomas Covenant" series. The accompanying illustrations are by Russ Nicholson, which is always a treat. Part IV of Andy Slack's "Expanding Universe" for Traveller focuses on social standing and psionics. "Boot Hill Encounters" by Dominic Beddow is, as its title suggests, a collection of random encounters for use with TSR's Boot Hill or other Wild West RPGs. I was surprised to see this article, short though it is, simply because, even in the United States, Western-themed RPGs have always been an acquired taste at best. I can't imagine the genre is any more popular in Britain, but perhaps this simply shows my ignorance.

"Open Box" reviews four products, starting with Boot Hill, which scores 8 out of 10. Also reviewed are GDW's Imperium (9 out of 10) and Snapshot (8 out of 10). The final review – by Don Turnbull – is the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide. Turnbull's review is, of course, effusive, so much so in fact that he offers no numerical score for the book. Instead, he says the following:

In the end, set the task of reviewing something to which I know I cannot do justice, all I can say is – can you afford to be without it?

I say again: it's little wonder to me that Turnbull would eventually be selected to head up TSR UK.

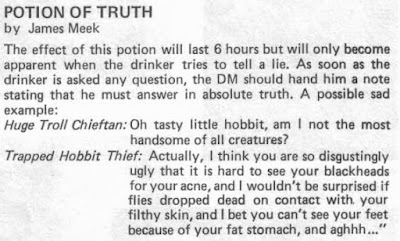

"Paths of the Lil" is a Gamma World adventure by James Ward. This is a scenario that's appeared in various forms over the years, including the second edition of the game published in 1983. Meanwhile, "The Fiend Factory" offers up five more monsters for use with Dungeons & Dragons. "Treasure Chest" presents seventeen new potions, a few of which are quite fun. Consider, for example, the potion of truth:

Mind you, I'm a fan of cursed items and think they ought to be used more often in games, so your mileage may vary.

Finishing out the issue is a brief report on Games Day V, which took place in October 1979. Accompanying the article are a number of photographs, some of which are quite charming, like this one:

All in all, I found issue #16 very enjoyable. As I mentioned at the start of this post, it looked and felt very much like the issues I would buy and devour several years hence. I'll be very curious to see if this one represents a turning point in the magazine's history and that the things I recognize here, like the cover and interior artwork, will become permanent features or if there will still be a few more bumps in the road.

November 7, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: Mother of Toads

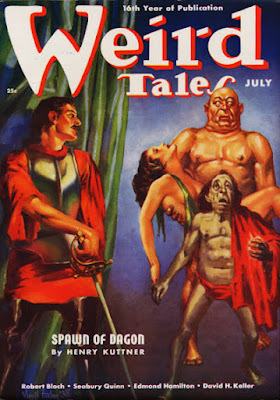

"Mother of Toads," which first appeared in the July 1938 issue of Weird Tales is a short but very disturbing story by Clark Ashton Smith. Like most of the tale set in the fictitious French province of Averoigne, this one touches upon sexual themes but in a way that's far removed from the prurience and titillation that were hallmarks of the pulps. Here, Smith uses sex – and the regret it can engender – as the basis for revulsion, horror, and, ultimately, doom.

"Mother of Toads," which first appeared in the July 1938 issue of Weird Tales is a short but very disturbing story by Clark Ashton Smith. Like most of the tale set in the fictitious French province of Averoigne, this one touches upon sexual themes but in a way that's far removed from the prurience and titillation that were hallmarks of the pulps. Here, Smith uses sex – and the regret it can engender – as the basis for revulsion, horror, and, ultimately, doom. The titular Mother of Toads is a witch called Mère Antoinette who dwells in the swamps not far from the village of Les Hiboux. Pale, obese, and possessing "eyes full-orbed and unblinking," she is also knowledgeable in the ways of potion making. It's for this reason that the villagers sometimes call upon Antoinette, including Pierre Baudin, the hapless apprentice of the apothecary Alain le Dindon.

Pierre's master had sent him to obtain from Antoinette a "vial contain[ing] a philtre of curious potency." He'd done this many times before, but he hated it, for the old woman clearly harbored a lust for him and regularly propositioned him: "Stay awhile tonight, my pretty orphan. No one will miss you in the village." Pierre was repulsed by such amorousness and hoped to finish his business with Antoinette as quickly as possible.

The witch was more than twice his age, and her charms were too uncouth and unsavory to tempt him for an instant. Also, her repute was such as to have nullified the attractions of a younger and fairer sorceress. Her witchcraft had made her feared among the peasantry of that remote province, where belief in spells and philtres was still common. The people of Averoigne called her La Mère des Crapauds, Mother of Toads, a name given for more than one reason. Toads swarmed innumerably about her hut; they were said to be her familiars, and dark tales were told concerning their relationship to the sorceress, and the duties they performed at her bidding. Such tales were all the more readily believed because of those batrachian features that had always been remarked in her aspect.

During his latest visit, Antoinette offers Pierre "a goodly measure of red wine" that she has mulled specifically for him. The youth is suspicious.

"I'll drink it," said Pierre a little grudgingly. "That is, if it contains nothing of your own concoction."

"'Tis naught but sound wine, four seasons old, with spices of Arabia," the sorceress croaked ingratiatingly. "'Twill warm your stomach … and …" She added something inaudible as Pierre accepted the cup.

Pierre drinks and declares that it is truly good wine but, having quaffed it quickly, he explains that he must be off to his master. Too late, he realizes the mistake he has made.

Even as he spoke, he felt in his stomach and veins the spreading warmth of the alcohol, of the spices … of something more ardent than these. It seemed that his voice was unreal and strange, falling as if from a height above him. The warmth grew, mounting within him like a golden flame fed by magic oils. His blood, a seething torrent, poured tumultuously and more tumultuously through his members.

Smith is a master of subtlety and suggestion, making excellent use of innuendo to make his points. He is equally adept at bluntness, often in service of horror. In what follows next, he employs both approaches, describing the "philterous ardor" that overtakes Pierre's senses as he suddenly sees in Mère Antoinette – and her propositions – in a new and disturbing light.

She led him to her couch beside the hearth where a great cauldron boiled mysteriously, sending up its fumes in strange-twining coils that suggested vague and obscene figures. The couch was rude and bare. But the flesh of the sorceress was like deep, luxurious cushions …

"The Mother of Toads" is an unsettling tale, not solely for the events it depicts or the frightful luxuriance Smith deploys in describing them but more for the realization that inevitably dawns on Pierre, as he understands what has transpired. It's that psychological element that I think elevates the story and stays with the reader after the story reaches its tragic, inevitable conclusion.

November 5, 2021

Random Roll: DMG, p. 12

Page 12 of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Masters Guide includes a short section of "Starting Level of Experience for Player Characters," which I found interesting. Gary Gygax begins by stating the obvious:

As a general rule the greatest thrill for any neophyte player will be the first adventure, when he or she doesn't have any real idea of what is happening, how powerful any encountered monster is, or what rewards will be gained from the adventure.

True words have not been written! I think, on some level, we're all hoping that, one day, we might re-experience this "greatest thrill." I further suspect that this hope plays a big role in why we continue to try out – and buy – new RPGs: "Maybe this game will remind me of what it was like when I first ventured into the Caves of Chaos when I was 10 years old."

This assumes survival, and you should gear your dungeon to accommodate 1st level players. If your campaign has a mixture of experienced and inexperienced players, you should probably arrange for the two groups to adventure separately, possibly in separate dungeons, at first.

I'm unsure if Gygax's use of the phrase "1st level players" is intentional or merely another example of the conflation between "player" and "player character" that can be found throughout the DMG.

Allow novice players to learn for themselves, and give experienced players tougher situations to face, for they already understand most of what is happening – quite unlike true 1st level adventurers of the would-be sort, were such persons actually to exist.

Combined with what Gygax wrote in the sentence immediately before this, I'm struck by how different my own early experiences were. In those days, it was not uncommon for neophyte players to join an already established campaign, bringing their newly-minted 1st-level characters to a party consisting of higher-level ones. I don't think this was anyone's preference, mind you, but it was a fairly standard practice and one we simply accepted as "the way of things." After all, if your 1st-level fighter survived even a single session adventuring with the higher-level party, he wouldn't be 1st level any longer.

If you have an existing campaign, with the majority of the players already above 1st level, it might be better to allow the few newcomers to begin at 2nd level or even 3rd or 4th in order to give them a survival chance when the group sets off for some lower dungeon level. I do not personally favor granting unearned experience level(s) except in circumstances such as just mentioned, for it tends to rob the new player of the real enjoyment he or she would normally feel upon actually gaining experience levels by dint of cleverness, risk, and hard fighting.

I completely agree with Gygax here. In the past, I have occasionally allowed an already experienced player to join a campaign with a higher-level character, but that's no longer my practice. Whenever a new player has joined my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, his character started at 1st level, even though the other characters were more experienced. I'm not sure I can justify this practice of mine beyond saying that I simply prefer that all characters earn their levels in the same fashion. After nearly seven years of continual play, it's worked out quite well and I see no reason to change it.

It has been called to my attention that new players will sometimes become bored and discouraged with the struggle to advance in level of experience, for they do not have any actual comprehension of what it is like to be a powerful character of high level. In a well planned and well judged campaign, this is not too likely to happen, for the superior DM will have enough treasure to whet the appetite of players, while keeping them hungry still, and always after that carrot just ahead. And one player's growing ennui can often be dissipated by rivalry, i.e. he or she fails to go on an adventure, and those who did play not only had an exciting time but brought back a rich haul as well.

My qualms about the phrase "the superior DM" to the contrary, Gygax speaks truly here – or at least it comports with my own experience as a referee over the years. I'd only add that it's not only treasure that can serve to whet the appetite of players. Just as often knowledge and other rewards are every bit as motivating. (Gygax's reference to rivalry between players is something I haven't experienced since I was a kid, but I concede it may well serve as a motivator in some groups.)

Thus, in my opinion, a challenging campaign and careful refereeing should obviate the need for immediate bestowals of levels of experience to maintain interest in the game. However, whatever the circumstances, if some problem such as this exists, it has been further suggested that allowing relatively new players to participate in a modular campaign game (assuring new players of characters of high level) would often whet their appetites for continued play at lower level, for they can then grasp what it will be like should they actually succeed in attaining proficiency on their own by working up their original characters and gaining high levels of experience.

By "modular campaign" does Gygax mean the use of adventure modules? If so, this would seem to suggest that he saw the purpose of these pre-made adventures to be, at least in part, to serve as a "training ground" for players in what it would be like to play at various levels. If that's right, I don't believe I've ever seen this sentiment expressed anywhere else before. Even if that's not what Gygax meant, it's nevertheless an intriguing idea and one I'm not sure I'd ever considered before. If nothing else, it possibly sheds some light on why TSR often published modules whose suggested levels were much higher than anything typically achieved in most campaigns.

November 3, 2021

Beasts, Men & Gods!

For those of you fascinated, as I am, by less well known RPGs from the first decade of the hobby, allow me to point you toward this site. Bill Underwood, creator of the game, Beasts, Men & Gods, has made its revised second edition from 1982 available as both a free electronic file and as a print-on-demand book.

For those of you fascinated, as I am, by less well known RPGs from the first decade of the hobby, allow me to point you toward this site. Bill Underwood, creator of the game, Beasts, Men & Gods, has made its revised second edition from 1982 available as both a free electronic file and as a print-on-demand book. Take a look!

Retrospective: RuneQuest Companion

About a year after the publication of original Dungeons & Dragons, its first supplement appeared. Subtitled Greyhawk, Supplement I offered up a grab bag of "new characters, new abilities, more spells to use, a horde of new monsters, heaps of new magical treasure, and various additions to the suggestions and rules for adventuring above and below the ground," most of which were drawn from Gary Gygax's D&D campaign of the same name. Two more supplements of a similar sort followed (Blackmoor and Eldritch Wizardry), thereby establishing a pattern for the way rules additions and suggestions were published in the hobby.

About a year after the publication of original Dungeons & Dragons, its first supplement appeared. Subtitled Greyhawk, Supplement I offered up a grab bag of "new characters, new abilities, more spells to use, a horde of new monsters, heaps of new magical treasure, and various additions to the suggestions and rules for adventuring above and below the ground," most of which were drawn from Gary Gygax's D&D campaign of the same name. Two more supplements of a similar sort followed (Blackmoor and Eldritch Wizardry), thereby establishing a pattern for the way rules additions and suggestions were published in the hobby.Chaosium was particularly prolific in producing supplements of this sort, though, rather than calling them "supplements," they called them "companions." Companions were published to support most of their RPGs, from Call of Cthulhu to Stormbringer to Ringworld, among others. Each of these companions presented a selection of rules and setting additions, expansions, options, and corrections. I've always appreciated this approach, since it both obviates the need for a new edition and gave the referee the choice of whether or not to include any of the new material printed in its pages.The RuneQuest Companion, first published in 1983, is a good example of what I mean. Over the course of 72 pages, the Companion presents nineteen articles by a wide variety of authors, each of which offers new insight into some aspect of RQ and its setting, Glorantha. As explained by Charlie Krank in his introduction to the book, the Companion was published in the wake of the cancelation of Wyrms Footnotesm the semi-regular 'zine that had previously provided RQ fans with more information about Glorantha and its history, cultures, and denizens. (It's interesting to note that Krank's explanation for the demise of Wyrms Footnotes is quite simple: "it costs too much money." As the publisher of a fanzine myself, I am deeply sympathetic with Krank's perspective.) The Companion, then, was intended to fill this particular gap, with the promise – unfulfilled, as it turned out, but then that's nothing new in the history of RuneQuest – of a new volume of the Companion "whenever we have accumulated 64–96 pages of top-notch articles."

The articles are quite varied. There's Sherman Kahn's "An Index to RuneQuest Cults," Alan LaVergne's solo adventure, "The Maze of Shaxry Oborok," and Greg Stafford's "Holy Country" (complete with a remarkable map). Meanwhile, Sandy Petersen presents his "Species Spotlight: Unicorns," which gives a unique Gloranthan spin on the legendary beasts and "More on Trolls," expanding on the information in Trollpak. There's also a fair bit of fiction (and poetry) set in Glorantha and few rules additions. What makes the Companion remarkable, though, is its diversity. Its pages aren't devoted to a single theme or topic. Instead, we're provided with articles and essays on many aspects of the game and its setting, with a particular emphasis on the latter. Indeed, looking back on it now, what really strikes me about the RuneQuest Companion is how few of its pages are devoted to new rules. Chaosium clearly understood the main draw of RQ was its setting of Glorantha. That's probably why I look on this book so favorably even now.

November 2, 2021

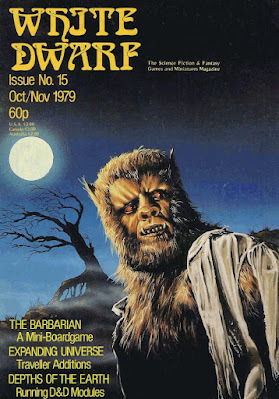

White Dwarf: Issue #15

The cover to issue #15 of White Dwarf (October/November 1979) is one that is seared into my memory. Though I wouldn't read, let alone buy, a copy of the magazine for several more years, I vividly recall seeing this particular cover, painted by Eddie Jones. I saw it sometime in early 1980, shortly after I'd started playing RPGs and had no idea what White Dwarf was or why the Hammer horror werewolf (from 1961's The Curse of the Werewolf) was featured on it. I believe my memories of this issue are reinforced by the fact that Games Workshop included it, along with several others, in their promotional advertising around the same period of time.

The cover to issue #15 of White Dwarf (October/November 1979) is one that is seared into my memory. Though I wouldn't read, let alone buy, a copy of the magazine for several more years, I vividly recall seeing this particular cover, painted by Eddie Jones. I saw it sometime in early 1980, shortly after I'd started playing RPGs and had no idea what White Dwarf was or why the Hammer horror werewolf (from 1961's The Curse of the Werewolf) was featured on it. I believe my memories of this issue are reinforced by the fact that Games Workshop included it, along with several others, in their promotional advertising around the same period of time.The issue begins with Roger Musson's "How to Lose Hit Points … and Survive." The article offers a lengthy (two and a half pages) alternative damage system for use with Dungeons & Dragons, one that suggests that some attacks deal hit point damage while others deal Constitution damage. Musson's idea is that hit points represent "energy and combat resources" rather than the capacity to withstand physical damage. They're a marker of fatigue, training, and luck, while Constitution is a truer representation of a character's ability to take wounds. It's an interesting idea and one I've seen suggested in other contexts over the years. Never having used a system like this, I couldn't see with any certainty if it works well or if it bogs the game down unnecessarily. Regardless, I found the article enjoyable in a way I usually don't when the author is suggesting a major overhaul of a core rules element of D&D.

Andy Slack's "Expanding Universe" for Traveller continues in this issue. This part, the third in the series, focuses on star system generation, aliens, and robots, three topics not covered in the three little black books of the 1977 boxed set. As usual, the additions Slack suggests are sensible and very much in keeping with the original rules of Traveller. In particular, I liked his largely straightforward means of determining the useful characteristics of planets, such as surface temperature, day length, and native lifeforms. They're much simpler than those that would be presented in Book 6: Scouts years later.

"The Barbarian" is a two-player game by Ian Livingstone. One player takes the role of a barbarian, named Vaarn, who is attempting to find a magic sword and shield by which he can bring about the reunification of mankind, whose civilization has fallen into decadence. The other plays the various creatures who oppose him in this quest. The rules are fairly simple, using two six-sided dice, and the issue includes a hex map and some counters to be cut out and used. The game reminds me a bit of a combination of Yaquinto's Hero and Heritage's Barbarian Prince, though much less complex than either of them.

Don Turnbull's "Descent into the Depths of the Earth" isn't a review of the D-series modules, which Turnbull had already done in a previous issue. Rather, it's a collection of suggestions for referees who intend to run those modules. Turnbull rightly points out that D1, D2, and D3 are all quite complex, filled with large combats, and, in a couple of cases, quite spare in details. Consequently, he draws attention to these instances and offers suggestions on how best to deal with them in play. Of particular interest to me is Turnbull's insistence that "figures or counters" be used to aid in the adjudication of many combats.

"Open Box" reviews two Metagaming microgames, Ice War (5 out of 10) and Black Hole (9 out of 10), as well as King Arthur's Knights by Chaosium (7 out of 10). The latter game is designed by Greg Stafford and demonstrates the late, great designer's lifelong fascination with the Arthurian cycle of legends. Also reviewed are three Judges Guild Traveller support products: Traveller Shield (7 out of 10), Traveller Logbook (9 out of 10), and Starships and Spacecraft (5 out of 10). Closing out the section is a very positive (9 out of 10) review of GDW's Animal Encounters for Traveller, a product I own but have never got much use out of over the years.

"Treasure Chest" is a very eclectic mix this month, starting with the usual collection of new magic items, but also including a system for "Determining Weight and Height" based on numerous factors (yawn!), an alternative to level drain (non-permanent Strength and Constitution points are lost instead), and advice on deciding which creatures are affected by the casting of a sleep spell. Articles like these are a reminder that gamers have always enjoyed arguing about and tinkering with rules. "Fiend Factory" offers up its usual selection of monsters for D&D none of which stood out as noteworthy in my biased opinion.

White Dwarf is now starting to look and feel more like the magazine I'd first pick up three years in the future. The mix of articles feels very like what I remember, in particular the heavy support for Traveller, alongside D&D. The only thing that's really missing are more articles about RuneQuest and Call of Cthulhu, two other mainstays of the magazine from the period when I read it regularly. In the case of CoC, that's understandable, since it won't be published until 1981 and RQ was featured in the previous issue. Still, it's fascinating watching the magazine come into itself.

November 1, 2021

"We're Doing Something Wrong."

I recently acquired One-Hour Skirmish Wargames by John Lambshead on the recommendation of a friend. It's a very interesting book from a number of perspectives and I might later do a full review of it. For the moment, though, I want only to draw your attention to a couple of paragraphs from the general introduction of the book, because I think they have a certain applicability to RPG design.

There is a school of thought that persists to this day that because skirmish wargaming involves few models that each model must have concomitantly special rules. Often the player has been required to micromanage actions. For example a gunman model might not just shoot, but (i) locate the target, (ii) draw his pistol, (iii) cock his pistol, (iv) aim his pistol, (v) pull the trigger. The player might even be called upon to write out orders in advance detailing all these actions. This approach has meant that skirmish games have had a tendency to become complicated models of real life.

I well recall playing a game of Cold War fighter combat (air games are often a sub-branch of skirmish games) in the early 80s where a single pass by two Tornados at an element of MIG 25s that might have taken ten to thirty seconds of real time actually required all afternoon to play. If game-time is longer than real-time then we're doing something wrong. (Italics mine)

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers