James Maliszewski's Blog, page 122

January 8, 2022

Fantasy Games on South of Watford

The episode, presented by Ben Elton, is quite well done and offers a solid dose of nostalgia for those of us old enough to remember those times. Among the interviewees are Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson of Games Workshop, as well as Albie Fiore of White Dwarf. The episode is only about 30 minutes long, but it's well worth your time. Take a look when you have the chance.

January 7, 2022

Heretical Thoughts

Was the second edition of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons really that bad?

Was the second edition of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons really that bad?I was thinking about this a couple of weeks ago, when I was going through my collection of TSR D&D products while compiling the Top 10 lists I posted last month. I no longer own almost anything from the 2e era except the Player's Handbook, Dungeon Master's Guide, and Monstrous Compendium, so I don't have a lot to go on. However, in flipping through them, I wasn't overcome with revulsion at the 2e rules, which, by and large, weren't all that different from their 1e counterparts. They're a little looser and more flexible in places – combat particularly – but, re-reading these books for the first time in perhaps a decade, there wasn't a lot I found inherently objectionable.

On the other hand, the presentation of 2e left much to be desired. I'm not even talking about the banal, occasionally conversational way in which it was written, though, to be fair, that is a disappointment, especially when compared to the glories of High Gygaxian. I'm also not talking about the awful layout and graphic design, with its awful rounded fonts and use of blue as a splash color, though, again, these weren't appealing choices. No, the bigger issue, I think, is the artwork, which is almost universally inferior to that of 1e, despite the fact that TSR now employed artists who were far better on a technical level than their predecessors. Despite this, there's very little inspirational in the art of 2e. I mean, take a look at this:

That may not be the worst piece of art to appear in the 2e Player's Handbook, but it's one I've always found off-putting and indeed more than a little silly, despite my fondness for small dragons. In my opinion, it's also pretty emblematic of the artwork we get in second edition: technically good but overwhelmingly mundane.

That may not be the worst piece of art to appear in the 2e Player's Handbook, but it's one I've always found off-putting and indeed more than a little silly, despite my fondness for small dragons. In my opinion, it's also pretty emblematic of the artwork we get in second edition: technically good but overwhelmingly mundane.

I wonder how many people's opinions of AD&D Second Edition are rooted largely in its artwork and overall presentation. As I said, I found the rules better than I recalled their being, before the endless churn of Complete X Handbooks and ever more esoteric settings obscured their clarity. Gary Gygax's original rules are still very much present in 2e. I'd suggest that, unless one is devoted to weapon speed factors or segments, it's perfectly possible to use 2e to play a game that is functionally very close to the Gygaxian original. I'd also suggest that, given the changes Gary himself envisioned for his own second edition, very little that lead designer David Cook implemented in the published second edition is too far beyond the pale. Indeed, I think Cook was probably a lot more conservative in his own rules changes than Gygax would have been, had he stayed at TSR long enough to complete his own revision.

But 2e's art and presentation are real problems, at least if you're someone whose conception of fantasy is more steeped in a pulpy, pre-Shannara mold. If one's tastes tend more toward fantastic realism, I would wager that 2e's illustrations were probably very much to your liking. If not, they're distracting at best and repellant at worst. That's too bad, I think, because, as I've noted, I don't think the rules of second edition AD&D are themselves a serious step down from those of first. At the same time, I can hardly fault anyone for disliking the look of the 2e books enough not to give their content a fair shake. I think esthetics are important, vital even, and that's especially true when dealing with imaginary places and creatures. Art helps draw one into fantasy, which is why it's key that it be appealing to its intended audience.

I can't shake the feeling that AD&D's second edition is more disliked in retrospect than it was at the time. I think some of this dislike is bound up in the publishing trajectory the game later took, with endless supplements and settings, as well as the sense that Gary Gygax had been ill-treated by the very company he founded. If so, this isn't fair to the game David Cook actually designed, which is somewhere in the vicinity of 80–90% mechanically identical to 1e, just better organized and explained. Certainly there are aspects of 2e that I'm not fond of, but many of these elements are optional and, once again, I don't think it's any mark against 2e that TSR would later over-emphasize these elements to the detriment of the solid foundation Cook laid down in 1989.

I played 2e when it came out and into the first half of the 1990s, though not as extensively as I played 1e. I remember having fun with it and indeed being quite impressed with it upon its initial release. My eventual drifting away from AD&D had very little to do with the game itself and much more to do with the fact that, by 1994 or so, I was simply tired of D&D (and traditional fantasy more generally), which I'd played more or less constantly for a decade and a half. Paging through my old copies of the 2e rulebooks reminded me of all of this and I'm glad of it. I'm in no danger of ever playing Second Edition again, but I'm glad to have been given the opportunity to re-evaluate my feelings about an edition of the game that I sometimes think gets more grief in old school circles than it deserves.

January 5, 2022

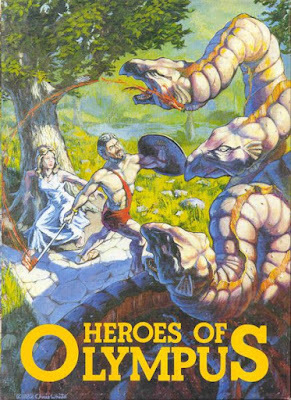

Retrospective: Heroes of Olympus

In the nearly half-century since the publication of Dungeons & Dragons, a great many roleplaying games have followed in its wake. Odds are good that you probably haven't heard of most of them, let alone had the chance to play them. That's certainly true in my case, for lots of reasons, including the youthful TSR fanboyism that limited my field of vision for too long. Consequently, I regularly encounter RPGs of which I'd never heard previously and that represent a part of the hobby's history that is otherwise obscure to me.

In the nearly half-century since the publication of Dungeons & Dragons, a great many roleplaying games have followed in its wake. Odds are good that you probably haven't heard of most of them, let alone had the chance to play them. That's certainly true in my case, for lots of reasons, including the youthful TSR fanboyism that limited my field of vision for too long. Consequently, I regularly encounter RPGs of which I'd never heard previously and that represent a part of the hobby's history that is otherwise obscure to me.Heroes of Olympus was completely unknown to me until very recently. Written by Dennis Sustare – author of Bunnies & Burrows and Swordbearer, as well as originator of the druid as a playable character class – and produced by Task Force Games in 1981, Heroes of Olympus, as its name suggests, is a roleplaying game steeped in the mythology of ancient Greece. That's a subject that's received far less attention than one might have expected, given the importance of those legends not just to Western culture as a whole but to popular adventure fiction (including RPGs).

A couple of months ago, a friend of mine indicated that he had long wanted to play this game and offered to start up a campaign, if a few other mutual friends and I were willing to participate. I was initially reluctant, to be sure, mostly due to the fact that I already participate in quite a few other roleplaying game campaigns and wasn't sure I could justify another. At the same time, I was very intrigued, both by the subject matter of Heroes of Olympus and aspects of its design. Having now played in it since late last year, I'm glad I set aside my reservations and did so.

Heroes of Olympus is explicitly modeled on the stories of Jason and the Argonauts, which are probably as close to RPG-style adventures as you can find in Greek myth. Character generation includes both random and point-buy elements, starting with one's ancestry, which is random. Most Heroes of Olympus player characters will be the sons of gods/mythological beings (e.g. nymphs) and/or royalty of one of the petty kingdoms that dot the eastern Mediterranean. For example, my own character is Eurymachos, son of King Autolykos of Imbros and the Muse Euterpe. Players allocate points among combat skills (sword, club, wrestling, etc.), physical attributes (great strength, excellent vision, etc.), and other skills (seamanship, riding, etc.). Game mechanics largely rely on percentile dice rolls, hence skills are rated 1–100.

As one might expect of a Greek-themed RPG, Heroes of Olympus involves lots of maritime travel between the lands of Greece and Asia Minor and the myriad islands of the region. Having a galley, as my character does, is thus a huge benefit, since it makes traveling from place to place easier. The general "time period" of the game is the immediate aftermath of the Trojan War, with the heroes doing great deeds during this tumultuous era. Many of those deeds involve fighting, which explains why the game includes three different combat systems, one of which covers naval battles. The other two cover duels between individuals and battles between heroes and "normal" men. These systems involve the allocation of points between attack, defense, initiative, and trickery (special maneuvers). It took me quite a while to wrap my head around the way these systems work, but, once I did, things ran more smoothly. They're still a little clunky and even tedious at times, especially when compared to simpler systems like those in D&D, but there's nevertheless a certain fun to be had in the way they handle battles.

Magic does exist in the game, though it seems mostly to be of divine origin. This makes sense, if one looks to the source material, where Greek heroes rarely rely on sorcery to achieve their ends. Still, a character favored by Hecate or Hermes might gain access to spells (as is the case for one of the PCs in the campaign in which I'm playing). Much more information is given about the gods themselves, as well as the various sorts of mythical beings one might encounter. It's all useful stuff, if limited in its scope. I imagine Sustare assumed referees and players alike could easily seek out information on Greek mythology to create their own material.

No one should forget that Heroes of Olympus is more than four decades old. This is not a modern RPG on almost any score and, even by the standards of the time in which it was written, it's, by turns, unclear, incomplete, and occasionally contradictory. Yet, it's also a great deal of fun – or at least that's been my experience. The Greek myths are a primal fount of adventure stories. Having the opportunity to play in that particular sandbox is a blast, even with a game whose rules are not always up to the task. I'd never argue that Heroes of Olympus is a lost classic of roleplaying game design, but it's got a lot to like about it, not least being the way it uses its ancient Greek inspirations as the basis for engaging sword-and-sandal exploits in a world full of gods and monsters. I wish I'd known about it sooner.

January 4, 2022

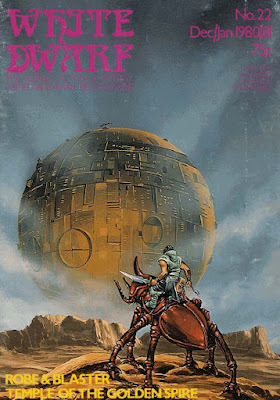

White Dwarf: Issue #22

Issue #22 of White Dwarf (December 1980/January 1981) features an unusual cover by Eddie Jones. I've mentioned in previous posts in this series how often WD covers mixed science fiction and fantasy elements. They did it so often that I've come to see it as one of the calling cards of British gaming. The arbitrary boundaries between genres seem much stronger in North America, likely due to the pernicious influence of marketing on this side of the Atlantic. I must sheepishly confess that I once accepted it unquestioningly and have since come to regret that. Live and learn!

Issue #22 of White Dwarf (December 1980/January 1981) features an unusual cover by Eddie Jones. I've mentioned in previous posts in this series how often WD covers mixed science fiction and fantasy elements. They did it so often that I've come to see it as one of the calling cards of British gaming. The arbitrary boundaries between genres seem much stronger in North America, likely due to the pernicious influence of marketing on this side of the Atlantic. I must sheepishly confess that I once accepted it unquestioningly and have since come to regret that. Live and learn!Ian Livingstone's editorial concerns the subject of the "best" RPG system. He offers no opinion of his own, preferring to state that the matter is, on some level, "purely a matter of taste." At the same time, he does suggest that it is the GM, not the rules, "who makes or breaks a campaign." As a younger man, I probably had some fairly strong opinions on this matter. Nowadays, I find the question almost nonsensical. With a couple of exceptions, rules have had rarely been the decisive element in my most enjoyable roleplaying experiences. Even when they were, it was more likely the people with whom I was playing who had the biggest impact – and that remains true to this day.

"Games Day '80" is a short article, accompanied by many photographs, recounting the events of the convention held in September 1980. There's sadly not much to note here, though some of the photos have a certain charm to them, particularly those depicting the Commodore PET computers on display at the con. "3D Dungeon Design" by Mervyn Lemon is another short article, this one offering ideas for using polystyrene to create tiles for use with fantasy miniatures. "Robe and Blaster" by Rick D. Stuart expands the rules of Traveller with benefits for characters who possess a high social standing. This is a topic about which I recall seeing many articles over the years, suggesting it was commonly seen as a "hole" in need of filling in the rules.

"Treasure Chest" presents eight new magic items by a variety of authors, including Roger E. Moore and Phil Masters. I remember Moore well from his contributions to Dragon, but I didn't realize until recently that he had written articles so widely. "Open Box" reviews four games, starting with Mythology by Yaquinto Games (9 out of 10) and Stellar Conquest by Metagaming (9 out of 10). Also reviewed is Asteroid Zero-Four by Task Force Gaming (6 out of 10) and The Gateway Bestiary by Chaosium (6 out of 10).

"Black Priests" by Lewis Pulsipher is a cleric sub-class that's more or less intended for evil cultists. It's a strange and very specialized class, focused on summoning monsters by appealing to dark gods. "The Search for the Temple of Golden Spire" by Barney Sloane is a tournament adventure for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. The scenario consists of a small wilderness area dotted with multiple ruins and other locales, including the titular temple. The basic set-up of the adventure is solid, though its actual execution is somewhat banal. The maps are quite nice, though, but that's typical of White Dwarf.

"Port Facilities" by S.L.A. McIntyre is another Traveller article, this time expanding on the types of facilities and services available at each type of starport. This issue's installment of the "Fiend Factory" presents "the Heavy Brigade," which are powerful, singular monsters, such as the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and Ungoliant, Queen of the Spiders. I like the idea behind such monsters, though none of those presented do much for me. Finally, "What the Numbers Mean" by Lewis Pulsipher is a brief examination of the meaning of ability scores in D&D. The intent behind it is to contextualize the range of scores from 3 to 18 within the wider human population in order to make sense of them. It's OK so far as it goes, but the article too short to offer any deep insights.

White Dwarf inches ever closer to the era with which I am more familiar. I continue to enjoy this exploration of its earlier days, though, since, if nothing else, they provide a window on the early 1980s that is a useful counterpoint to the way roleplaying, as a hobby and as an entertainment, has developed in the decades since.

January 3, 2022

The All-Seeing Eye

The 1980 Rankin-Bass Return of the King animated film is a strange thing on many levels and is probably deserving of multiple posts dissecting its content and presentation of J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth. For the moment, though, I only want to draw attention to a single, memorable image, that of the Witch-King of Angmar.

Take a look at his chest, which bears a symbol that we also see elsewhere in the film, such as on the tunic of the Mouth of Sauron.

Take a look at his chest, which bears a symbol that we also see elsewhere in the film, such as on the tunic of the Mouth of Sauron.

You can also see it on the orcish helmets Frodo and Sam don while traveling in Mordor.

You can also see it on the orcish helmets Frodo and Sam don while traveling in Mordor.

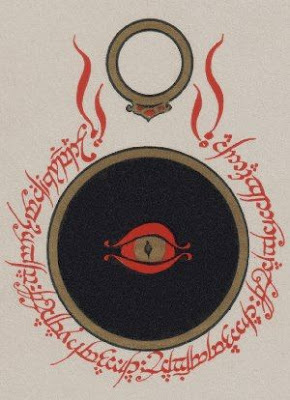

I think the symbol is meant to represent the Eye of Sauron, which Tolkien himself illustrated.

I think the symbol is meant to represent the Eye of Sauron, which Tolkien himself illustrated.

As you can see, there's only a very broad similarity between Tolkien's own depiction of the Eye and those used in the animated film. Tolkien's Eye does not have that bottom row of radiating lines, which might be eyelashes or might instead represent Sauron's baleful gaze. Whatever the intention, I think it's safe to say that the film version wasn't directly based on Tolkien's own illustration.

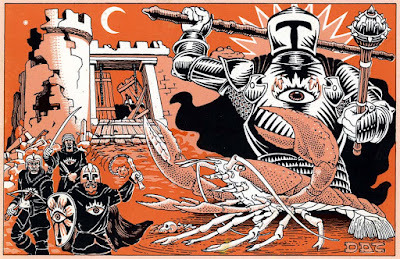

As you can see, there's only a very broad similarity between Tolkien's own depiction of the Eye and those used in the animated film. Tolkien's Eye does not have that bottom row of radiating lines, which might be eyelashes or might instead represent Sauron's baleful gaze. Whatever the intention, I think it's safe to say that the film version wasn't directly based on Tolkien's own illustration.I mention all of this because, the other day, when I was compiling illustrations to include in my two posts about my favorite illustrations of Golden Age D&D, I briefly contemplated including Dave Trampier's original 1979 cover to The Village of Hommlet.

It's an absolutely phenomenal illustration. From context, I believe it is meant to depict aspects of the Ruins of the Moathouse, such as the giant crayfish and the bandits. The helmeted figure is likely "the new Master," Lareth the Beautiful, who is described as possessing a suit of magic plate mail and wielding both a mace and a staff of striking. You'll notice that both Lareth and the bandits bear a stylized eye symbol on their chests. This symbol might be associated with the cult of the Elder Elemental Eye, a mysterious being first mentioned at the end of Hall of the Fire Giant King and that may have originally had some role to play in Gary Gygax's original conception of the Temple of Elemental Evil.

It's an absolutely phenomenal illustration. From context, I believe it is meant to depict aspects of the Ruins of the Moathouse, such as the giant crayfish and the bandits. The helmeted figure is likely "the new Master," Lareth the Beautiful, who is described as possessing a suit of magic plate mail and wielding both a mace and a staff of striking. You'll notice that both Lareth and the bandits bear a stylized eye symbol on their chests. This symbol might be associated with the cult of the Elder Elemental Eye, a mysterious being first mentioned at the end of Hall of the Fire Giant King and that may have originally had some role to play in Gary Gygax's original conception of the Temple of Elemental Evil.Regardless, it's hard not to look on that symbol and be reminded of the Eye of Sauron. Granted, such a symbol isn't the exclusive province of Tolkien. There are plenty of examples of it in prior history, going all the way back to at least ancient Egypt, if not before. Still, it's hard even for me, a dedicated defender of the notion that Dungeons & Dragons owes very little to Tolkien, not to wonder about the ultimate inspiration for this sinister sigil.

130 Years Ago Today ...

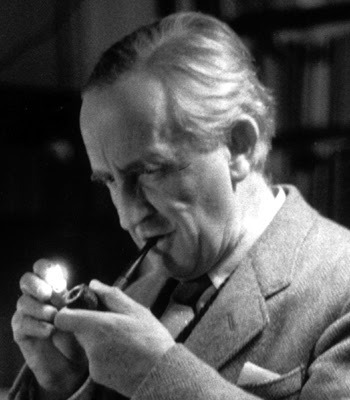

… John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born in Bloemfontein, South Africa (then the Orange Free State).

I find it difficult to know what to write on occasions like this. Partly, it's because I've already written many posts about Tolkien. What more could I add? Partly, it's because so many others have written much more insightful things and, again, what more could I add? As one of the founders of the modern fantasy genre and, by extension, so much of contemporary popular culture, is there anything left to say about J.R.R. Tolkien that hasn't already been said thousands of times before?

In the end, I'm not sure that matters. The truth is that most of us involved in this hobby are here, either directly or indirectly, because of the work of Tolkien. Whether or not one accepts Gary Gygax's repeated claim that Dungeons & Dragons owed little of its conception to the tales of Middle-earth, I think it's undeniable that D&D's success was founded on the popularity of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Likewise, the success of the fantasy genre as a whole is founded on the bedrock of Tolkien's myth cycle, however much lesser writers might wish it were otherwise. Without Tolkien, there'd likely be no appetite for doorstop fantasy trilogies – for good or for ill – not to mention many video games, heavy metal music, and panel van art. How many other authors have had such a profound and lasting influence?

I'm certain Tolkien himself would not have been comfortable with any of this. Certainly, he was pleased that his sub-creation had been so well received, but it was always a sideshow compared to his more serious academic work in the field of English philology. Furthermore, he often expressed, not unreasonably, the belief that many of his readers had misunderstood his work and the intent behind it. There is, for example, the famous story he recounts, in one of his letters, I think, of receiving a gift from a devotee in the form of a steel goblet on which had been inscribed the words found on the One Ring. Tolkien was appalled by this and used the gift as an ashtray. I can't begin to imagine what he would have thought of the fact that replicas of the One Ring itself are now readily available – and worn! – by people who claim to love his writing.

Despite my personal preference for pulp fantasy these days, I nevertheless remain indebted to Tolkien and his fiction, which I first encountered at a very impressionable age. He's not my go-to author when I wish to be inspired about fantastical places and events, but I would be lying to deny that his work has a hold on my imagination that few others can rival. That, I suppose, is the greatest compliment I can pay to him on the 130th anniversary of his birthday.

January 2, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Last Incantation

January is the month of Clark Ashton Smith's birth – along with several other notable writers – so I thought I might devote the next five Mondays to works that are part of his lesser known story cycles, such as Mars, Poseidonis, and Xiccarph. These cycles contain fewer stories than those of Averoigne, Hyperborea, and Zothique, which may partly explain why they have received comparatively little acclaim. That's a shame, because they're every bit as rich in both ideas and hypnotic prose as his better known efforts.

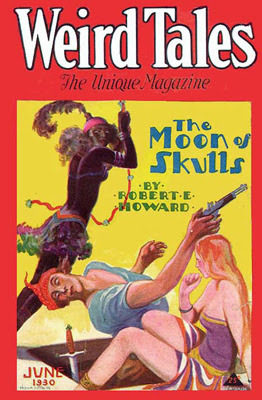

January is the month of Clark Ashton Smith's birth – along with several other notable writers – so I thought I might devote the next five Mondays to works that are part of his lesser known story cycles, such as Mars, Poseidonis, and Xiccarph. These cycles contain fewer stories than those of Averoigne, Hyperborea, and Zothique, which may partly explain why they have received comparatively little acclaim. That's a shame, because they're every bit as rich in both ideas and hypnotic prose as his better known efforts.A near-perfect case in point is "The Last Incantation," which first appeared in the June 1930 issue of Weird Tales. It's one of Smith's earliest published works of fiction and the influence of his years as a poet is quite evident. Indeed, the story is scarcely a story at all, being little more than a brief, melancholy vignette. Despite its concision, "The Last Incantation" is a thoughtful, heartfelt meditation on age and the limitations of memory. Re-reading it shortly after the turn of another year granted it a greater degree of poignancy than I had expected.

The tale concerns the magician Malygris, who dwelled in a tower "above the heart of Susran, capital of Poseidonis," the last outpost of the once-great civilization of Atlantis.

Malygris was old, and all the baleful might of his enchantments, all the dreadful or curious demons under his control, all the fear that he had wrought in the heart of kings and prelates, were no longer enough to assuage the black ennui of his days.

A long-time reader of Smith might well be tempted to roll his eyes upon reading this passage; he's already seen this many times before. Remember, though, how early CAS wrote "The Last Incantation." Consequently, Malygris is likely the first of Smith's sorcerers to be so afflicted and, as I will argue, his affliction is a truly moving one.

We soon learn that Malygris has familiar, who took "the form of a coral viper with pale green belly and ashen mottlings" and lived within the head of a unicorn that hung above the door to his chambers. The demon keeps watch over his master, as he attempts – and fails – to derive any pleasure from the power and possessions he has amassed after a long lifetime. He takes no joy in his present and sees little hope for a positive change in his future.

Then Malygris groped backward to the years of his youth, to the misty, remote, incredible years, where, like an alien star, one memory still burned with unfailing luster – the memory of the girl Nylissa, whom he had loved in days ere the lust of unpermitted knowledge and necromantic domination had entered his soul. He had well-nigh forgotten her for decades, in the myriad preoccupations of a life so bizarrely diversified, so replete with occult happenings and powers, with supernatural victories and perils; but now, at the mere thought of this slender and innocent child, who had loved him so dearly when he too was young and slim and guileless, and who died of a sudden mysterious fever on the very eve of their marriage, the mummy-like umber of his cheek took on a phantom flush, and deep down in his orbs was a sparkle like the gleam of mortuary tapers.

Feeling genuine emotion for the first time in so long, an idea occurs to Malygris and he asks his familiar:

"Viper, am I not Malygris, in whom is centered the mastery of all occult lore, all forbidden dominations, with dominion over the spirits of earth and sea and air, over the solar and lunar demons, over the living and the dead? If I so desire, can I not call the girl Nylissa, in the very semblance of all her youth and beauty, and bring her forth from the never-changing shadows of the cryptic tomb, to stand before me in this chamber, in the evening rays of this autumnal sun?

His familiar replies that he can indeed do this. Even so, Malygris hesitates and wonders aloud whether he should do this – a moment of doubt not common in Smith's haughty necromancers, who rarely question the probity of their actions.

The viper seemed to hesitate. Then, in a slow and measured hiss: "It is meet for Malygris to do as he would. Who, save Malygris, can decide if a thing be well or ill?"

"In other words, you will not advise me?" the query was as much a statement as a question, and the viper vouchsafed no further utterance.

With that, Malygris casts aside his doubts and commits to "the ritual that summons the departed," so that he might once more see Nylissa, whom he had loved in his youth and whose memory, even now, quickens his heart and his fills his soul with longing.

Of course, this being a Clark Ashton Smith story, I do not think anyone will be surprised to learn that events do not go at all as Malygris had hoped. Where "The Last Incantation" differs from other similar stories (such as "Xeethra") in that Malygris suffers neither a grisly fate nor a divine curse. Rather, he learns a lesson – a painful one, to be sure, but a lesson nonetheless, one from which I think more of us, in this nostalgia-soaked age, might well profit.

December 30, 2021

My Top 10 D&D Illustrations of the Golden Age (Part II)

Here is the second part of the list I began earlier this week. As always, a reminder that this list is highly personal. The entries here were judged on a variety of criteria, resulting in entries that fall somewhere in that wide, nebulous space between my personal favorites and objectively best with the former likely playing a far larger role in my final determination. Nevertheless, I genuinely do think all the entries below are excellent illustrations of my own early experiences of Dungeons & Dragons, experiences that still influence my view of the game to this day.

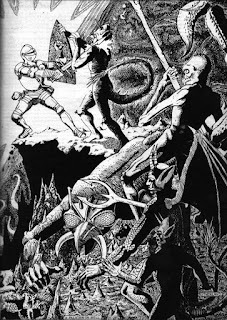

5. Holmes Basic Frontispiece (1977)

Like the cover to the J. Eric Holmes-edited Basic Set, my fondness for this particular piece is no doubt colored by its placement as the very first piece of art inside the Basic rulebook. Consequently, it's seared into my memory in much the same way as the cover itself. However, there's more to my fondness for the piece than primacy of memory. This is a terrific action scene, one depicting two doughty fighters in historical armor – a signature element of Sutherland's art – holding the line against a veritable horde of pig-faced orcs, while a magic-user casts a spell from the safe higher ground afforded by the nearby spiral staircase. I like it because it shows an adventuring party, albeit a small one, in action in a way that suggests the use of tactics. Likewise, I adore how many orcs there are. This is not a fair fight by any means; in fact, it looks downright desperate. This is what dungeon adventuring was like before the appearance of the notion of "balanced encounters." It can't get any more old school than this.

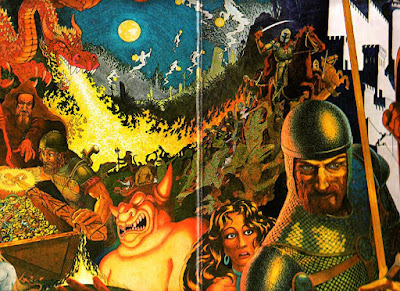

Like the cover to the J. Eric Holmes-edited Basic Set, my fondness for this particular piece is no doubt colored by its placement as the very first piece of art inside the Basic rulebook. Consequently, it's seared into my memory in much the same way as the cover itself. However, there's more to my fondness for the piece than primacy of memory. This is a terrific action scene, one depicting two doughty fighters in historical armor – a signature element of Sutherland's art – holding the line against a veritable horde of pig-faced orcs, while a magic-user casts a spell from the safe higher ground afforded by the nearby spiral staircase. I like it because it shows an adventuring party, albeit a small one, in action in a way that suggests the use of tactics. Likewise, I adore how many orcs there are. This is not a fair fight by any means; in fact, it looks downright desperate. This is what dungeon adventuring was like before the appearance of the notion of "balanced encounters." It can't get any more old school than this.4. AD&D Dungeon Masters Screen (1979)

What a marvelous piece by Dave Trampier! It's really got everything: a dragon, mounted combat against lizard men, the discovery of a magic sword, ghosts, a brave swordsman protecting a woman – a rarity in Tramp's artwork – and, of course, the demon idol of Players Handbook fame (more on that soon). All in all, it's a superb montage of many of the activities that one might have expected from play in a D&D campaign. It also very nicely showcases just how talented Trampier was and of what he might have been capable had TSR valued him more. Like many pieces on my Top 10 list, this is a piece that makes me want to play D&D. Trampier beautifully evokes all the heroism, wonder, and terror to be found in a good game session. It's one of his best efforts and surely deserves to be celebrated.

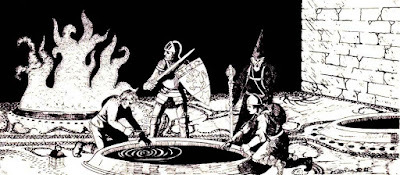

What a marvelous piece by Dave Trampier! It's really got everything: a dragon, mounted combat against lizard men, the discovery of a magic sword, ghosts, a brave swordsman protecting a woman – a rarity in Tramp's artwork – and, of course, the demon idol of Players Handbook fame (more on that soon). All in all, it's a superb montage of many of the activities that one might have expected from play in a D&D campaign. It also very nicely showcases just how talented Trampier was and of what he might have been capable had TSR valued him more. Like many pieces on my Top 10 list, this is a piece that makes me want to play D&D. Trampier beautifully evokes all the heroism, wonder, and terror to be found in a good game session. It's one of his best efforts and surely deserves to be celebrated.3. Room of Pools (1977)

This illustration, from the module

In Search of the Unknown

, is one of my favorites – along with the dungeon chamber it depicts. I was so in love with the Room of Pools that I shamelessly included a version of it in many of my early dungeons. It's not hard to understand why. The Room of Pools is a near perfect example of old school dungeon design principles. There are lots of pools, some of which offer boons and others banes, and it's up to the players to figure out which ones are which, based on cleverness, observation, and trial and error. I'm a huge fan of rooms like this and enjoy sitting back and watching the players' minds work, as they try to puzzle out what's in front of them. Sutherland captures this dynamic perfectly here. He also depicts an adventuring party – a little larger this time – and that always tickles my fancy.

This illustration, from the module

In Search of the Unknown

, is one of my favorites – along with the dungeon chamber it depicts. I was so in love with the Room of Pools that I shamelessly included a version of it in many of my early dungeons. It's not hard to understand why. The Room of Pools is a near perfect example of old school dungeon design principles. There are lots of pools, some of which offer boons and others banes, and it's up to the players to figure out which ones are which, based on cleverness, observation, and trial and error. I'm a huge fan of rooms like this and enjoy sitting back and watching the players' minds work, as they try to puzzle out what's in front of them. Sutherland captures this dynamic perfectly here. He also depicts an adventuring party – a little larger this time – and that always tickles my fancy. 2. A Paladin in Hell

2. A Paladin in HellThis Dave Sutherland illustration, from the AD&D Players Handbook, simply had to be on this list, as I long ago deemed it "my favorite D&D illustration of all time." More than a decade on from that original post, I largely stand by that assessment. It remains my favorite piece in the entirety of the PHB, as well as the best depiction of a paladin in all of Dungeons & Dragons artwork. What prevents my including it in the top slot is its specificity. This scene depicts a lone character fighting against foes in a very unusual situation. How often do D&D characters venture to Hell itself to take on the forces of the Enemy? Not very often, I'd wager. Likewise, D&D is about groups of characters working together to explore dungeons and relieve them of their treasures. There's plenty of space for individual heroism, of course, but, much as I love this illustration, I don't think the situation it depicts is in any way typical of those found in the average game session. But it's a solid number 2.

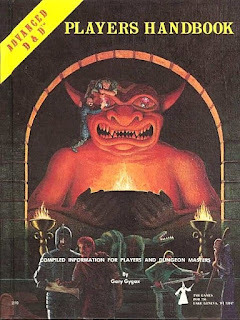

1. AD&D Players Handbook Cover (1978)

1. AD&D Players Handbook Cover (1978)Was there really any doubt about the number 1 spot? I don't believe there's ever been a piece of artwork for Dungeons & Dragons that is more well recognized and iconic. It is unquestionably the best cover of any D&D rulebook ever and perhaps even the single best evocation of what D&D was about in its early days. It's got pretty much everything you'd want in such a cover: the aftermath of a battle against lizard men, looting, planning, the use of maps, and the great demon idol itself. The idol is what really sells the piece for me. It's simultaneously attractive and repellent, redolent with the kind of mystery I expect in good dungeon features. I'm not sure I can say anything about the piece that hasn't been said hundreds of times before and better. This is a case where the artwork really does speak for itself. Magnificent.

December 29, 2021

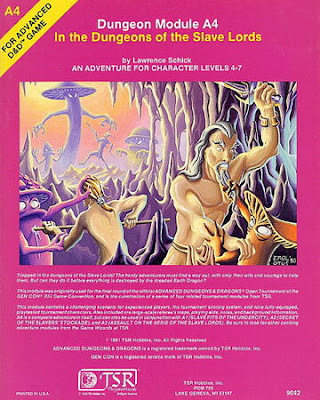

Retrospective: In the Dungeons of the Slave Lords

I'll briefly reiterate what I wrote in my retrospective post of Slave Pits of the Undercity: I have conflicting feelings about the entirety of the "Slave Lords" series of modules. On the one hand, the central conceit of these adventures – taking down a cabal of slavers – is a terrific one very much in keeping with the pulp fantasy roots of Dungeons & Dragons. It's not hard to imagine Conan or Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser engaged in such an endeavor. On the other hand, the modules, as published, feel very contrived and formulaic, owing no doubt to their origins as GenCon tournament modules. There's good stuff in all four of the A-series modules, but none of them quite achieve their full potential in my opinion, which is a shame.

I'll briefly reiterate what I wrote in my retrospective post of Slave Pits of the Undercity: I have conflicting feelings about the entirety of the "Slave Lords" series of modules. On the one hand, the central conceit of these adventures – taking down a cabal of slavers – is a terrific one very much in keeping with the pulp fantasy roots of Dungeons & Dragons. It's not hard to imagine Conan or Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser engaged in such an endeavor. On the other hand, the modules, as published, feel very contrived and formulaic, owing no doubt to their origins as GenCon tournament modules. There's good stuff in all four of the A-series modules, but none of them quite achieve their full potential in my opinion, which is a shame.

That's especially so in the case of the final module in the series, In the Dungeons of the Slave Lords. Written by Lawrence Schick, the adventure is geared toward characters of levels 4–7, like all of its predecessors, though its introductory "Notes for the Dungeon Master" repeatedly points out that "the player's skill, not the character's level, will determine success." That's because it assumes the characters failed in their assault on the aerie of the slave lords (in the module of this name) and were taken captive. Rather than slay the PCs, the slave lords instead throw them into their dungeons, "totally bereft of equipment and spells." Schick comments on this initial situation as follows:

Many players think of their characters in terms of their powers and possessions, rather than as people. Such players will probably be totally at a loss for the first few minutes of play. It is likely that they will be angry at the DM for putting them in such an "unfair" situation. They will demand or beg concessions. DO NOT GIVE THEM ANY HELP, even if they make you feel sorry for them. Inform the players that they must rely on what they have, not what they used to have, and that this includes their brains and their five senses. Good players will actually welcome the challenge of this scenario. All players will ultimately enjoy the module much more if they out on their own resources, rather than with what hints and clues the DM gives them.

Schick accurately predicted the reactions of my friends with whom I played; they were incensed to have had all their characters' gear taken away. I suspect this reaction was commoner if the module was used as part of regular campaign play, as it was in mine, than in a tournament situation, whose players, in my limited experience, are more accepting of such contrivances. Much more interesting, though, is Schick's insistence that the referee neither give the players any help nor feel sorry for them. "Good players," he intones, "will … welcome the challenge." He was accurate in that prediction as well. Once they got past the initial shock of their characters being tossed, nearly naked and unarmed, into dark, dank, caverns, they started to have fun figuring out how best to survive.

That's the main reason why I consider In the Dungeons of the Slave Lords perhaps the most interesting of the A-series modules: it does something unique, namely force the players to use their wits to keep their characters alive. Of course, it probably helps that many of the opponents in the eponymous dungeons are fairly weak – kobolds and giant insects of various kinds – but there are still enough genuine threats to keep them on their toes. This is no cakewalk.

And then there are the myconids, for which I have an inordinate fondness. There's just something about mushrooms and fungi generally that I not only find weirdly appealing but that screams "fantasy!" to me. I suppose my boyhood reading of Lewis Carroll played a role in this peculiar fixation of mine. Regardless, I love the myconids, who are not wholly indifferent to the characters' plight. Indeed, if they agree to perform a service to the myconid king, it will reveal to them an easier means of escaping the dungeons. I have always liked the inclusion of neutral factions in dungeons and Schick does a good job, I think, of showing the potential inherent in such encounters.

The conclusion of the module involves a final confrontation with the slave lords amidst a volcanic eruption that is destroying the villains' home base. Like many aspects of the module, it's all rather contrived and, in my opinion, something of an anticlimax not just to this module but to the whole series. Mind you, disappointment is my overall feeling about these adventures. There's unquestionable potential in them, along with a number of genuinely clever sections and elements, but, in the end, the whole winds up being much less than its parts. I can't help but think that, with a bit more work, the A-series could have been truly memorable, on par with the truly great modules of D&D's past.

December 28, 2021

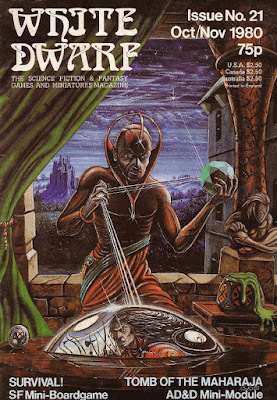

White Dwarf: Issue #21

Issue #21 of White Dwarf (October/November 1980) begins with an editorial by Ian Livingstone in which he opines about magic systems in fantasy roleplaying games. "Not wishing to sit on the fence," Livingstone stakes the claim that D&D's Vancian system is "now a little outdated." He then lauds "the power point system of RuneQuest" as being "more logical." While I have no problem with Livingstone's preference for RQ's system over that of D&D, I find his claim that the latter's system is "outdated" odd. What does that term even mean in this context? The suggestion that RuneQuest's system is "more logical" is equally odd, especially given that Livingstone notes earlier in his own editorial that "there is no real way of testing the fallibility of each system." He's right about that, which is why all we have are personal preferences.

Issue #21 of White Dwarf (October/November 1980) begins with an editorial by Ian Livingstone in which he opines about magic systems in fantasy roleplaying games. "Not wishing to sit on the fence," Livingstone stakes the claim that D&D's Vancian system is "now a little outdated." He then lauds "the power point system of RuneQuest" as being "more logical." While I have no problem with Livingstone's preference for RQ's system over that of D&D, I find his claim that the latter's system is "outdated" odd. What does that term even mean in this context? The suggestion that RuneQuest's system is "more logical" is equally odd, especially given that Livingstone notes earlier in his own editorial that "there is no real way of testing the fallibility of each system." He's right about that, which is why all we have are personal preferences.

"Lore of the Land" by Andrew Finch is a collection of four new D&D character classes based on characters from the Thomas Covenant novels of Stephen R. Donaldson. Three of these classes are spellcasters, while the fourth one is the bloodguard, which are broadly similar to monks. "Merchants" by Roger E. Moore describes one more D&D character class, the merchant of the title. In Moore's version, merchants are similar to thieves and bards, in that they possess a variety of percentile-based skills focused on personal interactions. The class is clearly very specialized but I can certainly see its appeal.

"Open Box" presents three longer reviews, the first of which is for GDW's Azhanti High Lightning (garnering a score of 8 out of 10). Also reviewed are a pair of micro-games from Task Force Games, Intruder (6 out of 10) and Valkenburg Castle (8 out of 10). I never saw the two games reviewed here, but micro-games were quite trendy in the hobby for a time, with some of them, such as Ogre, proving quite successful and influential. "Survival!" by Bob McWilliams is an example of such a mini-game, whose complete rules and game map are included in this issue/ The game is solitaire, with the player taking the role of Jardine, the sole survivor of a starship whose lifeboat crash landed on the world of Coryphire. The world is uninhabited, but there is an Imperial Scout Service Aid Station located on it. By braving Coryphire's wildlife and environment, he might be able to reach the station alive.

"Treasure Chest" presents fifteen new D&D spells submitted by a variety of authors, including such notables as Roger E. Moore and Mark Galeotti. "Fiend Factory" does something very interesting. Instead of simply presenting seven new D&D monsters, they're all contextualized within a wilderness area known as "One-Eye Canyon." It's quite clever in my opinion and made me much more interested in the new monsters than I have been in previous installments of "Fiend Factory."

Bob McWilliams pens another "Starbase" column, this time presenting a short scenario – more of a situation really – involving a wilderness trek during a winter storm. It's fascinating to me how many early Traveller adventures take place in the wilderness or battles against the elements. It's definitely not what I imagine most people think of when they hear the words "science fiction adventure in the far future." The issue ends with "Tomb of the Maharaja" by S. Hartley. It's a short adventure set in an ostensibly Indian-themed dungeon, but that felt to me more like something out of ancient Egypt, complete with a mummy at the end.

Issue #21 felt like a slight step backwards for White Dwarf, especially after a string of truly excellent issues. That's the nature of submission-driven magazines, I suppose, so I can't judge the issue too harshly, even if its content wasn't quite as appealing to me as that in its immediate predecessors.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers