James Maliszewski's Blog, page 119

January 30, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Flower-Women

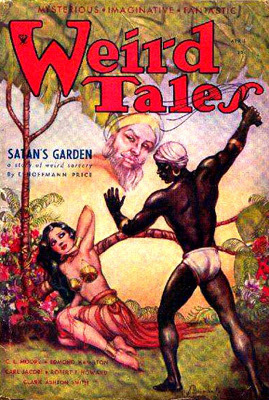

Clark Ashton Smith clearly had a fondness for the character of Maal Dweb. After the completion of "The Maze of the Enchanter," he penned a second story set on the alien world of Xiccarph, entitled "The Flower-Women." Like its predecessor, the story met with resistance from the editor of Weird Tales, Farnsworth Wright, who called it "well done" but deemed it "a fairy story rather than a weird tale proper." Lovecraft, who was ardent admirer of many of Smith's efforts, didn't think much of this particular yarn either, calling it "below par" in a contemporary letter to R.H. Barlow.

Clark Ashton Smith clearly had a fondness for the character of Maal Dweb. After the completion of "The Maze of the Enchanter," he penned a second story set on the alien world of Xiccarph, entitled "The Flower-Women." Like its predecessor, the story met with resistance from the editor of Weird Tales, Farnsworth Wright, who called it "well done" but deemed it "a fairy story rather than a weird tale proper." Lovecraft, who was ardent admirer of many of Smith's efforts, didn't think much of this particular yarn either, calling it "below par" in a contemporary letter to R.H. Barlow. Wright eventually changed his opinion and "The Flower-Women" was published in the May 1935 issue of Weird Tales. The story opens with Maal Dweb experiencing intolerable ennui, an emotional state he resolves to alleviate.

"There is but one remedy for this boredom of mine," he went on — "the abnegation, at least for a while, of that all too certain power from which it springs. Therefore, I, Maal Dweb, the ruler of six worlds and all their moons, shall go forth alone, unheralded, and without other equipment than that which any fledgling sorcerer might possess. In this way, perhaps I shall recover the lost charm of incertitude, the foregone enchantment of peril. Adventures that I have not foreseen will be mine, and the future will wear the alluring veil of the mysterious. It remains, however, to select the field of my adventurings."I doubt I'm alone in finding this set-up quite compelling – and reminiscent of the kind of thing a high-level D&D character might do after finding his most recent adventures insufficiently challenging. Maal Dweb then consults his magical orreries and resolves to pay a visit to the farthest planet of the star system, Votalp.

Votalp, a large and moonless world, revolved imperceptibly as he studied it. For one hemisphere, he saw, the yellow sun was at that time in total eclipse behind the sun of carmine; but in spite of this, and its greater distance from the solar triad. Votalp was lit with sufficient clearness. It was mottled with strange hues like a great cloudy opal; and the mottlings were microscopic oceans, isles. mountains, jungles, and deserts. Fantastic sceneries leapt into momentary salience, taking on the definitude and perspective of actual landscapes, and then faded back amid the iridescent blur. Glimpses of teeming, multifarious life, incredible tableaux, monstrous happenings, were beheld by Maal Dweb as he looked down like some celestial spy.

By means of "a deep and hueless cloud," which affords Maal Dweb "access to multiple dimensions and deeply folded realms of space conterminate with far worlds," the mighty sorcerer makes his way to Votalp. There, he makes his way into a valley where heard "an eerie, plaintive singing, like the voices of sirens who bewail some irredeemable misfortune."

The singing came from a sisterhood of unusual creatures, half woman and half flower, that grew on the valley bottom beside a sleepy stream of purple water. There were several scores of these lovely and charming monsters, whose feminine bodies of pink and pearl reclined amid the vermilion velvet couches of billowing petals to which they were attached. These petals were borne on mattress-like leaves and heavy, short, well-rooted stems. The flowers were disposed in irregular circles, clustering thickly toward the center, and with open intervals in the outer rows.

Maal Dweb approached the flower-women with a certain caution; for he knew that they were vampires. Their arms ended in long tendrils, pale as ivory, swifter and more supple than the coils of darting serpents, with which they were wont to secure the unwary victims drawn by their singing. Of course, knowing in his wisdom the inexorable laws of nature, he felt no disapproval of such vampirism; but, on the other hand, he did not care to be its object.

I find it interesting that, while Maal Dweb is the protagonist of this tale, Smith does not shy away from the fact that he is an evil man. His ready acceptance of vampirism contrasts with the reactions of more traditional pulp fantasy protagonists, who would likely view the flower-women as frightful creatures. Instead, Maal Dweb finds them "lovely and charming." There isn't a hint of fear or condemnation, only the recognition that he must be wary of them.

The sorcerer nevertheless forgets himself and falls prey to their "wild and sweet and voluptuous singing, like that of the Lorelei." He finds that the melody "fire[s] his blood with a strange intoxication" and he is soon drawn to the flower-women. Once in their presence, he regains something of his mental faculties and uses his "power of divination" to learn more about them. He then discovers that five of their kind had been uprooted over the course of five successive mornings by "certain reptilian beings, colossal in size and winged like pterodactyls, who came down from their new-built citadel." Known as the Ispazars, these reptile-men were themselves magicians of no mean talent, as well as "masters of an abhuman science."

Now, through an errant whim, in his search for adventure, he had decided to pit himself against the Ispazars, employing no other weapons of sorcery than his own wit and will, his remembered learning, his clairvoyance, and the two simple amulets that he wore on his person.

"Be comforted," he said to the flower-women, "for verily I shall deal with these miscreants in a fitting manner."

With that, "The Flower-Women" suddenly becomes a different story, one in which the villainous Maal Dweb, the tyrant of six worlds, becomes more than the protagonist of the story. To the flower-women, at least, he becomes a hero, as the remainder of the story chronicles his efforts on their behalf, avenging the destruction of their kind by the Ispazars. It's quite a startling thing to read and I found myself wondering whether or not Smith had intended this shift, however subtle, to point toward a change in Maal Dweb's character. Even if that wasn't his intention, he does seem to signal an intention to tell more stories of Maal Dweb's adventures among the worlds he rules.

Unfortunately, it was not to be. "The Flower-Women" is the second and last story of Xiccarph. No further stories of the magician ever appeared and, so far as I know, there's no evidence any more were planned. It's a pity, as Maal Dweb is a genuinely interesting character, and I can't help but wonder what more might have awaited him. In just two stories, he went from antagonist to protagonist to something approximating a hero. That's the kind of transformation that few writers could pull off, but Clark Ashton Smith made a good start of it here.

January 28, 2022

The Sorcerer of Xiccarph

In light of a recent Pulp Fantasy Library entry, I thought readers might enjoy this write-up of Clark Ashton Smith's sorcerer, Maal Dweb. The description originally appeared in the "Giants in the Earth" column appearing in issue #30 of Dragon (October 1979), written by Lawrence Schick and Tom Moldvay (though I suspect, given his love of Smith, that Moldvay was likely the author of this particular character).

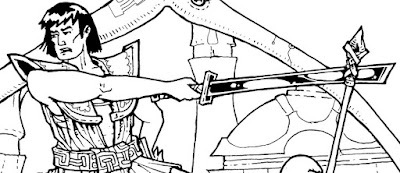

The Many Deaths of Aíthfo hiZnáyu

Aíthfo as drawn by Zhu BajieeRegular readers will recall that, two weeks ago, one of the longstanding characters in my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, Aíthfo hiZnáyu, died as a result of EPT's instant death rule. Shocking though this was, this wasn't the first time Aíthfo had died. He had died once before, also as a result of a bad dice roll – this time a saving throw versus spells – and the consequences of his death and unusual resurrection played a huge role in the progress of the campaign.

Aíthfo as drawn by Zhu BajieeRegular readers will recall that, two weeks ago, one of the longstanding characters in my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, Aíthfo hiZnáyu, died as a result of EPT's instant death rule. Shocking though this was, this wasn't the first time Aíthfo had died. He had died once before, also as a result of a bad dice roll – this time a saving throw versus spells – and the consequences of his death and unusual resurrection played a huge role in the progress of the campaign.Several years ago, long before the first session I discussed on this blog, the player characters were exploring a weird temple in the jungles of the Achgé Peninsula of the Southern Continent. The temple had numerous guardians, both human and monstrous, who attempted to stop the characters' explorations. During one particularly fraught combat, Aíthfo decided to undertake a very risky maneuver. Aíthfo, you see, is an adventurer, an optional EPT character class created by Glenn Rahman (designer of Divine Right, among other things) that appeared in issue #31 of Dragon. The adventurer is a jack-of-all-trades class that mixes fighting and sorcery. Though Aíthfo is one of the group's front-line warriors, he frequently supplements his battle tactics with the handful of spells he knows.

On Tékumel, magic can be "short circuited" by the proximity of any sort of metal. This isn't generally a problem, since most of its major cultures don't use metal for weapons or armor, relying instead on the fiberglass-like hide of the Chlén-beast. However, metal arms and armor do exist and are highly valued for their strength. Aíthfo at this time possessed both a steel sword and steel armor. His usual practice was to divest himself of these before casting a spell, but he felt he had no time to do so in this instance and decided to take a chance that there might be no ill effects from doing so. Unfortunately for him, things did not go as planned and the resulting spell failure slew him instantly (the aforementioned saving throw having failed).

The other characters took possession of Aíthfo's body and resolved to find some way to restore him to life, though they had no idea what that might be. At the moment, they were deep in the jungles of the peninsula, far from their home base of Linyaró, The nearest outpost of civilization was the Naqsái city-state of Mánmikel, of which they'd heard but never before visited. At best, it was several days away; at worst, it was several weeks. Since they intended to go there eventually anyway, the group headed into the general direction of Mánmikel. Znayáshu made use of his embalming skills to preserve Aíthfo's body against the heat and humidity of the region, though even his skills had their limits.

Eventually, the group did make it to Mánmikel, where they sought out anyone locally who might have the power to raise Aíthfo from the dead. This led them to the leader of the city-state, a priest who acted as regent for his god, Eyenál (many Naqsái city-states are supposedly ruled by deities, who act through high priests who govern in their names). The regent agreed to do return Aíthfo to life, on the condition that an alliance be struck between Mánmikel and Linyaró, an alliance that would ultimately result in a war against a second Naqsái city-state. The characters agreed, as they had no other option. Aíthfo was the governor of Linyaró and his death would destabilize an already unstable situation.

What the characters didn't understand at the time was that the "resurrection" the regent offered was, in fact, a ritual that called on Eyenál to take Aíthfo's mortal remains as his vessel. Aíthfo awoke alive, but he also gained the ability to speak and understand Naqsái tongues, as well as to see the presence of magical energy. The priests of Eyenál told him that, in time, the incarnation of Eyenál would grow stronger, as more of the god's power manifested in him. At the end, Aíthfo as he was would be no more, replaced by the living god Eyenál.

The campaign at that point focused on the complications of the alliance between Mánmikel and Linyaró, as well as the consequences of Aíthfo's sharing his body with a strange, foreign deity. None of this was planned out in advance by me. I largely made up the details on the fly, once it became clear the other players wished to find a way to resurrect Aíthfo. Initially, I was prepared to let Aíthfo stay dead and that would be the end of it, but an idea started to form in my mind during the sessions while the PCs were traveling to Mánmikel and decided to run with it. In the end, this led to many wild and wonderful places, culminating with the divine energy housed in Aíthfo's body being emptied out to seal a vast interplanar nexus point that served as prison for several malign entities. Since then, Aíthfo resumed his life as a merely mortal being – his mortality proven definitively with his death a couple of sessions ago. But an idea from long ago, one that first sprang into existence during his original death percolated in my brain and I thought it might be worth running with it. That the characters once again thought they might try to restore their clan mate and boon companion to life again only made it easier to do so. So it was that, last week, the characters discovered that something strange was happening to the body of Aíthfo. His body was not only stitching itself back together but it radiated potent energies of Stability, one of the two foundational elements of the Tsolyáni worldview. Soon, he was alive again, with no memory of the intervening time or how he had managed to return to life.

Many old school referees are opposed to the idea of spells like raise dead and believe quite strongly that dead characters should stay dead. I'm sympathetic to this perspective. At the same time, I believe that a character's death is an opportunity that can be seized upon to explore the game world and its cosmology. This is especially true in a weird and wonderful setting like Tékumel, which is filled with unanswered questions and unexplained elements. That's why Aíthfo hiZnáyu is once more among the living. Why and what this means for the campaign are things the players will discover in the weeks and months to come.

January 27, 2022

A World of Sorcery and Science

Artwork by Zhu Bajiee and Graphic Design by Lester B. Portly

Artwork by Zhu Bajiee and Graphic Design by Lester B. Portly

January 26, 2022

Speaking of Micro-Games

Here's an advertisement from issue #24 of White Dwarf, highlighting a collection of "pocket games" by Task Force Games. I never played any of those shown here, but I remember seeing Valkenburg Castle and Battlewagon on store shelves in the early 1980s. In case, it's another reminder of just how many games of this sort were published by a number of publishers at the time.

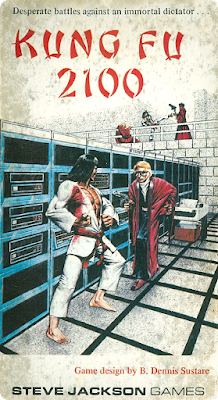

Retrospective: Kung Fu 2100

I'm a huge fan of "micro-games" (also known as "mini-games" and "pocket games," among many other monikers). I was an avid player of TSR's forays into this field, but it was the designs published by Steve Jackson Games that first introduced me to the concept. Broadly speaking, most micro-games existed in a space somewhere between boardgames and wargames and came in small containers, whether ziplock bags, plastic clamshells, or pocket boxes. All micro-games featured relatively simple rules and components, which is why they were generally playable in about an hour or so. This was a big part of the appeal of micro-games to me and my friends. We'd often pull out Revolt on Antares or Ogre when we were waiting for the rest of the gang to assemble for D&D. They were a fun way to pass the time, even if you were just watching others play them (most micro-games were two-player).

I'm a huge fan of "micro-games" (also known as "mini-games" and "pocket games," among many other monikers). I was an avid player of TSR's forays into this field, but it was the designs published by Steve Jackson Games that first introduced me to the concept. Broadly speaking, most micro-games existed in a space somewhere between boardgames and wargames and came in small containers, whether ziplock bags, plastic clamshells, or pocket boxes. All micro-games featured relatively simple rules and components, which is why they were generally playable in about an hour or so. This was a big part of the appeal of micro-games to me and my friends. We'd often pull out Revolt on Antares or Ogre when we were waiting for the rest of the gang to assemble for D&D. They were a fun way to pass the time, even if you were just watching others play them (most micro-games were two-player). Last night, a friend mentioned a micro-game I hadn't thought about in a long time, Kung Fu 2100. Originally appearing in the pages of issue #30 of The Space Gamer (August 1980), the game would eventually be released as a separate product later that same year. That's how I first encountered it, as I rarely saw, let alone read The Space Gamer. Nevertheless, I was a keen player of Steve Jackson's micro-games (especially Car Wars) and snapped them up whenever I came across new ones. In the case of Kung Fu 2100, that happened while on vacation with my family and I chanced upon a little game store that was surprisingly well stocked with games I'd never seen before, including this one.

Kung Fu 2100 is wonderfully strange. Designed by Dennis Sustare, whose contributions to the hobby are many, the game's premise is a delightful goulash of 1970s pop cultural concerns, from cloning to martial arts to the end of human civilization. According to the history presented in its rulebook, human cloning is perfected in 2006, a complicated process that requires not only high technology – take a look at the computer banks and dot matrix printer depicted on the cover! – but the wealth to afford it. The cloning process involves the growth of a physical copy of the biological donor, as well as a copy of the donor's personality, memories, and experiences. Taken together, this opens the door to virtual immortality to those with financial means, setting off riots and unrest, as the masses realize what this means for society. The powerful, who come to be known as CloneMasters, eventually restore order, but only be repressive means, right down to outlawing the possession of most modern technology by anyone but themselves.

If this sounds utterly ridiculous, it is, but, as the premise of a game where one player takes the role of members of a secret society pledged to end the tyranny of the CloneMasters, it's perfect. Members of the Society of Thanatos, as it is known, train from childhood to use only their bodies to fight, since most weaponry is now forbidden to anyone but the CloneMasters and their servants, some of whom are Thanatos turncoats. The masses, who revere these martial artists as heroes, call them Terminators and cheer them on. The game itself focuses on an attack by the Terminator player on a CloneMaster fortress, with the goal of slaying the CloneMaster who dwelled within. The goal of the CloneMaster player, of course, is to prevent this from happening.

Kung Fu 2100 consisted of a fortress map, some counters, a rulebook, and record sheets – fairly standard components for a micro-game. The sequence of play involves multiple phases of movement, combat, and recovery within each turn, with the Terminator and CloneMaster players alternating between them. Combat, specifically hand-to-hand combat, is quite interesting, in that Terminators (and their enemy counterparts, the Janizaries [sic] or "Jellies") having a choice of tactics to choose from, such as Iron Fist, Lightning Foot, Monkey Soul, and Body of Mist. These tactics are compared to one another on a combat results table, with some each having situational advantages and disadvantages. It's a neat little system that's both easy to use and flavorful. Like many micro-games, Kung Fu 2100 also includes rules for solo play, which is useful on days when no one else is available.

Sadly, this wasn't a game I played much back in the day, not for lack of interest. However, with so many other micro-games available to us, we tended to opt for those that we'd played before, leaving Kung Fu 2100 an also-ran at best. I'm not quite sure what happened to my copy of it. After my conversation last night, I find myself wishing I still had it, if only to take a closer look at its components and luxuriate in the warmth of late '70s pop culture cranked up to 11. Even better would be to get the chance to play it again.

January 25, 2022

Dungeon Master

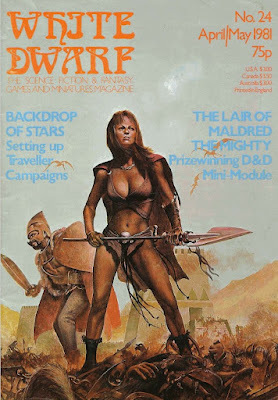

White Dwarf: Issue #24

Issue #24 of White Dwarf (April/May 1981) features a cover by Dave Pether, an artist whose name I don't recognize. Ian Livingston's opening editorial touches on the growing popularity of roleplaying as a hobby, noting that "Last year TSR sold 500,000 sets of D&D." Whether that figure is strictly accurate or not, it's nevertheless a useful reminder of just how successful Dungeons & Dragons was, despite being, in Livingstone's words, "an esoteric hobby." He later suggests that the success of RPGs has led to an overall improvement in their quality, not just in their physical appearance, but also in their designs, as "no manufacturer can afford to have a turkey in his range." Opinions vary, of course, but I'm not sure this was truly the case in early 1981, but it's undeniably the case that RPGs had, by this point, come a long way from "three badly written rulebooks in a little box."

Issue #24 of White Dwarf (April/May 1981) features a cover by Dave Pether, an artist whose name I don't recognize. Ian Livingston's opening editorial touches on the growing popularity of roleplaying as a hobby, noting that "Last year TSR sold 500,000 sets of D&D." Whether that figure is strictly accurate or not, it's nevertheless a useful reminder of just how successful Dungeons & Dragons was, despite being, in Livingstone's words, "an esoteric hobby." He later suggests that the success of RPGs has led to an overall improvement in their quality, not just in their physical appearance, but also in their designs, as "no manufacturer can afford to have a turkey in his range." Opinions vary, of course, but I'm not sure this was truly the case in early 1981, but it's undeniably the case that RPGs had, by this point, come a long way from "three badly written rulebooks in a little box."Lewis Pulsipher continues "An Introduction to Dungeons & Dragons" with a second installment dedicated to "Dungeon Mastering styles." He identifies four such styles, which he labels "simulation," "wargame," "absurd," and "novel." Simulation, as you might expect, is concerned with "reflect[ing] reality as much as possible." Pulsipher associates this style with games like Chivalry & Sorcery and then boldly asserts that simulationists "have no place in D&D." The wargame style is "how D&D is designed to be played" and prioritizes character survival and enrichment as the the game's primary goals. The absurdist style "condones unbelievable occurrences" and "arbitrary" outcomes. This style, I suspect, is that of the "funhouse dungeon." In Pulsipher's view, "the average game tends to fall between wargame and absurd game." The final style is "an oral novel in which the players are participating characters." The article teases out the strengths and weaknesses (in Pulsipher's opinion, of course) of each style and their consequences for a campaign. While I can't say I agree with all of its perspective, it is a genuinely interesting article that, if nothing else, gives the reader a glimpse into how some viewed D&D and its play at the time.

"Backdrop of Stars" by Andy Slack is a Traveller article focused on building a campaign setting. Slack goes over the pros and cons of using GDW's Third Imperium versus "rolling your own" and then looks at the various decisions the referee must make in the latter case. It's a solid, "meat and potatoes" article of the sort that I used to enjoy when I was young and inexperienced. Meanwhile, "Open Box" reviews three games I've never played and a Traveller adventure. Said adventure is Twilight's Peak, which I recently included as one of my Top 10 Traveller adventures (it scores 10 out of 10 here). The games reviewed are Eon's Quirks (9 out of 10), Yaquinto's Shooting Stars (8 out of 10), and Games Workshop's own Valley of the Four Winds (9 out of 10). I mentioned before that I'm not a fan of magazines running reviews of their own publisher's products, but it was standard practice once upon a time (and perhaps still is).

"Detectives" by Marcus L. Rowland is a character class for use with AD&D. The detective is like a cross between a thief and ranger, with a small selection of detection spells. It's an intriguing idea for inclusion in certain types of campaigns, but I don't see it as having wide utility. "The Lair of Maldred the Mighty" by Mark Byng is a lengthy AD&D adventure for a party of high-level characters led by a cleric or paladin. The scenario concerns an expedition to the secret lair of an evil wizard the past, who once ruled a kingdom in thrall to devils. There's perhaps the core of a good idea here, but it's so densely written and buried under unnecessary detail that it's hard to say for sure.

"Laser Sword and Foil" is a very short Traveller article by Bob McWilliams in which he touches upon the adventure possibilities in starship malfunctions. McWilliams says he will expand upon these possibilities in a future article. "Alignment in Role-Playing Games" by O.C. Macdonald begins as an overview of the concept before inevitably noting that, outside of D&D, few games use this concept, which is just as well, because it "adds little to the game." What an unexpected conclusion …

"Fiend Factory" presents a five silly monsters in honor of April Fool's Day. They range from the bonacon, based on genuine medieval legend, to the llort (a reverse troll, which degenerates) and the Dungeon Master. The last is fairly amusing, actually, and I'll post its full description in an upcoming post. "Special Rooms, Tricks & Traps" describes four examples of the kind of thing you might find in Grimtooth's Traps (complete with a diagram in one case). Not being an avid user of traps, it's difficult for me to judge these, but, on first glance, they seem decent enough. One is written by Roger E. Moore, which, as a longtime reader of Dragon, is fun to see.

All in all, this was a pretty good issue of White Dwarf – or at least one I enjoyed reading!

January 24, 2022

Are You An … Enslaved God?

January 23, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Death of Malygris

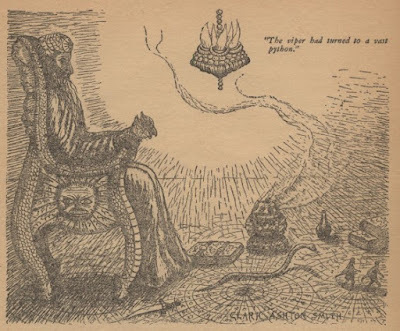

The final story of Smith's Poseidonis cycle was, appropriately, "The Death of Malygris." By his own account, he was pleased with the tale, particularly for its inclusion of "much genuine occultism and folklore." The editor of Weird Tales, the redoubtable Farnsworth Wright, didn't think much of the story and rejected it as "more like a prose poem than a story" – a common criticism of Smith's tales he rejected. H.P. Lovecraft, on the other hand, admired it, calling it "splendid" in a letter to Robert Bloch. Smith would later re-submit "The Death of Malygris" to Wright, who was more well inclined this time. He not only published the story in the April 1934 issue of Weird Tales, but even commissioned Smith to provide an accompanying illustration as well.

The final story of Smith's Poseidonis cycle was, appropriately, "The Death of Malygris." By his own account, he was pleased with the tale, particularly for its inclusion of "much genuine occultism and folklore." The editor of Weird Tales, the redoubtable Farnsworth Wright, didn't think much of the story and rejected it as "more like a prose poem than a story" – a common criticism of Smith's tales he rejected. H.P. Lovecraft, on the other hand, admired it, calling it "splendid" in a letter to Robert Bloch. Smith would later re-submit "The Death of Malygris" to Wright, who was more well inclined this time. He not only published the story in the April 1934 issue of Weird Tales, but even commissioned Smith to provide an accompanying illustration as well.The sorcerer Malygris, who had previously appeared in "The Last Incantation" (ironically, the first episode of the Poseidonis cycle), had long exercised power over Susran, capital of Poseidonis, power greater than that of even its king, Gadeiron. Recently, rumors arose that Malygris had at long last died, a claim denied by the other wizards of the city, but one that Gadeiron and his chief advisor, the magician Maranapion, hoped to be true. Because Malygris was a "master of illuding shows, of feints, and beguilements," Gadeiron believes that the old sorcerer pre-emptively made use of his enchantments to hide the fact that he has died, so that, even in death, he might still lord it over the people of Susran. For this reason, the king addresses the assembled wizards.

"Not idly have I called ye to this crypt, O sorcerers of Susran: for a work remains to be done. Verily, shall the corpse of a dead necromancer tyrannize over us all? There is mystery here, and a need to move cautiously, for the duration of his necromancy is yet unverified and untested. But I have called ye together in order that the hardiest among ye may take council with Maranapion, and aid him in devising such wizardry as will now expose the fraud of Malygris, and evince his mortality to all men, as well as to the fiends that follow him still, and the ministering monsters."

Seven of the twelve wizards agree to assist Maranapion in this endeavor. Two others, the brothers Nygon and Fustules, conceived an "audacious plan" of their own. During the next night, they carefully stole into the tower of Malygris, which they soon found devoid of any guardians or protections. Emboldened by this, they sought out the chamber of Malygris, at the center of which contained his "chair of primeval ivory" upon which sat "the old archimage … peering with stark, immovable eyes."

Nygon and Fustules felt their awe return upon them, remembering too clearly now the thrice-baleful mastery that this man had wielded, and the demon lore he had known, and the spells he had wrought that were irrefragable by other wizards. The specters of these things rose up before them as if by a final necromancy. With down-dropped eyes and humble mien, they went forward, bowing reverentially. Then, speaking aloud, in accordance with their predetermined plan, Fustules requested an oracle of their fortunes from Malygris.

There was no answer, and lifting their eyes, the brothers were greatly reassured by the aspect of the seated ancient. Death alone could have set the grayish pallor on the brow, could have locked the lips in a rigor as of fast-frozen clay. The eyes were like cavern-shadowed ice, holding no other light than a vague reflection of the lamps. Under the beard that was half silver, half sable, the cheeks had already fallen in as with beginning decay, showing the harsh outlines of the skull. The gray and hideously shrunken hands, whereon the eyes of enchanted beryls and rubies burned, were clenched inflexibly on the chair-arms which had the form of arching basilisks.

"Verily," murmured Nygon, "there is naught here to frighten or dismay us. Behold, it is only the lich of an old man after all, and one that has cheated the worm of his due provender overlong."

Perhaps predictably for a Clark Ashton Smith yarn, the true situation is not as the wizard brothers believe it to be. One of the familiars of Malygris, the viper featured in "The Last Incantation," springs upon them, while a voice echoes "Fools! ye dared to ask me for an oracle. And the oracle is – death!"

Meanwhile, Maranapion, knowing nothing of the fates of Nygon and Fustules, led the seven remaining wizards in a series of "impious charms and unholy conjurations, and fouler chemistries" intended to prove that Malygris is indeed dead, as he suspected. They start with a spell of invultuation, the crafting of plasmic copy of Malygris, which they cursed with their spells so that, by the principle of sympathy, the body of Malygris might decay. Then, making use of "the blue, monstrous eye of the Cyclops" – a crystal ball – they watch as their enemy seated in the tower above Susran slowly rotted.

Too easy, the reader might think and indeed it is. Malygris did not ascend to the heights of power in Poseidonis without being well prepared against the machinations of his foes, especially those as potent as King Gadeiron's wizardly advisors, as the reader soon discovers. "The Death of Malygris" is a story of hubris and revenge, filled with images of creeping doom and putrescence. It's thus a fitting end to the stories of Poseidonis, the last outpost of Atlantis.

Smith's own depiction of Malygris in his chair.

Smith's own depiction of Malygris in his chair.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers