James Maliszewski's Blog, page 121

January 13, 2022

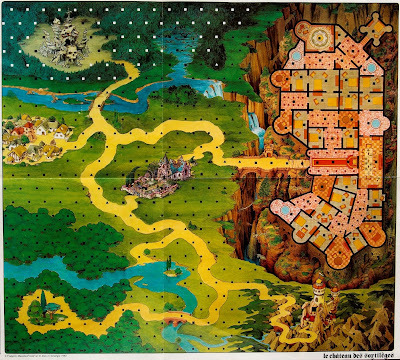

Le Château des Sortilèges

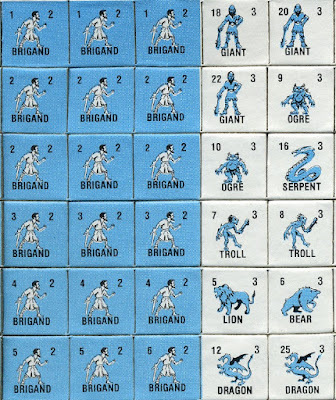

The influence of Dungeons & Dragons on Le Château des Sortilèges is very clear, particularly when you look at its counters.

The influence of Dungeons & Dragons on Le Château des Sortilèges is very clear, particularly when you look at its counters.

The depictions of the zombie, ghoul, troll, and goblin all look remarkably like those in the AD&D Monster Manual. For comparison, here's Dave Trampier's goblin from the MM:

The depictions of the zombie, ghoul, troll, and goblin all look remarkably like those in the AD&D Monster Manual. For comparison, here's Dave Trampier's goblin from the MM:

The second collection of counters also includes illustrations that are obviously derivative of those in the Monster Manual. Pay close attention to the demon, for example, which appears to have been cribbed from Sutherland's Asmodeus. Several of the other counters show resemblances to artwork by both Trampier and Dave Sutherland.

The second collection of counters also includes illustrations that are obviously derivative of those in the Monster Manual. Pay close attention to the demon, for example, which appears to have been cribbed from Sutherland's Asmodeus. Several of the other counters show resemblances to artwork by both Trampier and Dave Sutherland.

I'd never heard of Le Château des Sortilèges before and am grateful to reader Adamo Dagradi for sharing these images with me. The late 1970s and early 1980s were a fascinating time, as many of the foundational concepts we now associate with fantasy were in the process of being formed. I imagine this process was especially fascinating in countries outside the English-speaking world about which I know comparatively little. Le Château des Sortilèges is a good example of what was happening in France during this period. I have no doubt there are many more fantasy games like this one that offer insight into the early development of the genre.

I'd never heard of Le Château des Sortilèges before and am grateful to reader Adamo Dagradi for sharing these images with me. The late 1970s and early 1980s were a fascinating time, as many of the foundational concepts we now associate with fantasy were in the process of being formed. I imagine this process was especially fascinating in countries outside the English-speaking world about which I know comparatively little. Le Château des Sortilèges is a good example of what was happening in France during this period. I have no doubt there are many more fantasy games like this one that offer insight into the early development of the genre.

January 12, 2022

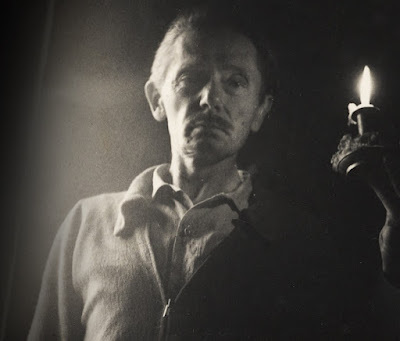

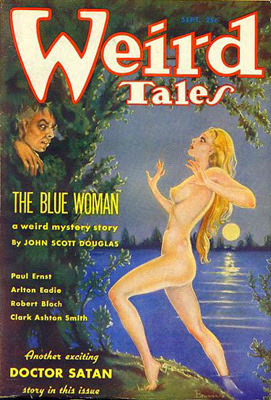

"I am the emperor of dreams"

I can think of no better way to commemorate the 129th anniversary of the birth of Clark Ashton Smith than to quote, as I will below, the first stanza from his 1922 poem, "The Hashish Eater (or The Apocalypse of Evil)." This is likely Smith's most famous poem, written nearly a decade before his name first appeared in the pages of Weird Tales. Smith, one must recall, began his literary career as a poet, the protégé of George Sterling. Likewise, in the years following the deaths of both his friend, H.P. Lovecraft, and his parents, Smith abandoned fiction entirely to returned to poetry, a pursuit that, along with sculpture, occupied him for the remainder of his life. Smith wrote fiction to pay the bills, but it was poetry that mattered most to him, hence my decision to mark his birthday with this excerpt.

I can think of no better way to commemorate the 129th anniversary of the birth of Clark Ashton Smith than to quote, as I will below, the first stanza from his 1922 poem, "The Hashish Eater (or The Apocalypse of Evil)." This is likely Smith's most famous poem, written nearly a decade before his name first appeared in the pages of Weird Tales. Smith, one must recall, began his literary career as a poet, the protégé of George Sterling. Likewise, in the years following the deaths of both his friend, H.P. Lovecraft, and his parents, Smith abandoned fiction entirely to returned to poetry, a pursuit that, along with sculpture, occupied him for the remainder of his life. Smith wrote fiction to pay the bills, but it was poetry that mattered most to him, hence my decision to mark his birthday with this excerpt.***

Bow down: I am the emperor of dreams;I crown me with the million-colored sunOf secret worlds incredible, and takeTheir trailing skies for vestment when I soar,Throned on the mounting zenith, and illumeThe spaceward-flown horizons infinite.Like rampant monsters roaring for their glut,The fiery-crested oceans rise and rise,By jealous moons maleficently urgedTo follow me for ever; mountains hornedWith peaks of sharpest adamant, and mawedWith sulphur-lit volcanoes lava-langued,Usurp the skies with thunder, but in vain;And continents of serpent-shapen trees,With slimy trunks that lengthen league by league,Pursue my flight through ages spurned to fireBy that supreme ascendance; sorcerers,And evil kings, predominantly armedWith scrolls of fulvous dragon-skin whereonAre worm-like runes of ever-twisting flame,Would stay me; and the sirens of the stars,With foam-like songs from silver fragrance wrought,Would lure me to their crystal reefs; and moonsWhere viper-eyed, senescent devils dwell,With antic gnomes abominably wise,Heave up their icy horns across my way.But naught deters me from the goal ordainedBy suns and eons and immortal wars,And sung by moons and motes; the goal whose nameIs all the secret of forgotten glyphsBy sinful gods in torrid rubies writFor ending of a brazen book; the goalWhereat my soaring ecstasy may standIn amplest heavens multiplied to holdMy hordes of thunder-vested avatars,And Promethèan armies of my thought,That brandish claspèd levins. There I callMy memories, intolerably cladIn light the peaks of paradise may wear,And lead the Armageddon of my dreamsWhose instant shout of triumph is becomeImmensity's own music: for their feetAre founded on innumerable worlds,Remote in alien epochs, and their armsUpraised, are columns potent to exaltWith ease ineffable the countless thronesOf all the gods that are or gods to be,And bear the seats of Asmodai and SetAbove the seventh paradise.

Impossible Whoppers

January 11, 2022

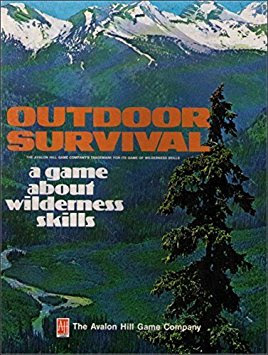

Retrospective: Outdoor Survival

I don't think I'd ever heard of Outdoor Survival prior to 2007. That's the year when I first started looking seriously into the history of Dungeons & Dragons, with a special focus on the original 1974 version of the game. What I soon discovered is that this rather odd 1972 Avalon Hill game played a role, albeit a minor one, in the development of D&D. Nowadays, I think this fact is pretty well known, even among those who don't play old school RPGs, but, at the time, it was news to me. This is in spite of the fact that Volume 1 of the Little Brown Books includes Outdoor Survival on page 5, as the second entry in its list of "recommended equipment," right after D&D itself.

I don't think I'd ever heard of Outdoor Survival prior to 2007. That's the year when I first started looking seriously into the history of Dungeons & Dragons, with a special focus on the original 1974 version of the game. What I soon discovered is that this rather odd 1972 Avalon Hill game played a role, albeit a minor one, in the development of D&D. Nowadays, I think this fact is pretty well known, even among those who don't play old school RPGs, but, at the time, it was news to me. This is in spite of the fact that Volume 1 of the Little Brown Books includes Outdoor Survival on page 5, as the second entry in its list of "recommended equipment," right after D&D itself.The actual use of Outdoor Survival in D&D isn't explained until fairly late in OD&D, about halfway through the third and final volume. There, in a section entitled "The Wilderness," it's suggested that the referee use the game's board for "off-hand adventures in the wilderness," which is to say, adventures whose wilderness locales are not determined by the referee beforehand. Because of this, it was once quite fashionable in the OSR to base one's starting campaign map on the one in Outdoor Survival, a fad I myself could not resist.

None of this says anything about Outdoor Survival itself, though. As I said in my opening paragraph above, it's designed by James F. Dunnigan, a legend in the wargames world. His first design, Jutland, was published by Avalon Hill in 1967, followed by many others, including PanzerBlitz in 1970 (also from AH). Dunnigan was also the founder of SPI and, believe it or not, the designer of the Dallas RPG. It's worth noting here that the game indicates that it was "produced and jointly distributed by the Avalon Hill Game Company … and Stackpole Books." Unlike Avalon Hill, Stackpole Books still exists and is a publisher of nonfiction books about arts and crafts, travel, and the outdoors. (As I understand it, Dunnigan claims, in his The Complete Wargames Handbook, to have designed Outdoor Survival as part of a bet about his ability to design a game on any subject.)

In addition to the game rules and the components needed to play, Outdoor Survival included a 24-page booklet entitled "A Primer about Wilderness Skills for Players of the Game." This is an honest-to-goodness handbook on the basics of surviving in the wild, covering everything from direction finding to killing and tracking game to first aid and more. Flipping through it reminded me of Boy Scout Handbook I had in elementary school. Its back page is an advertisement for larger treatments of all these topics in books sold by, you guessed it, Stackpole Books.

The game proper is comparatively simple. As its title suggests, it's intended as "a simulation of the essential conditions for staying alive when unprotected man is beset by his environment." The celebrated game board represents a wild area consisting of 13,200 square miles, with a wide variety of terrain types (woods, rough, desert, swamp, etc.). This area is divided into hexagons five kilometers (three miles) across. This makes me wonder if OD&D's use of five-mile hexes is the result of a misreading of the rules to Outdoor Survival or a deliberate choice on the part of Arneson and/or Gygax. I doubt I'm the first person to have noticed this seeming discrepancy.

Play depends on which of five scenarios one chooses. They consist of "Lost," "Survival," "Search," "Rescue," and "Pursue," each with slightly different rules and victory conditions. In general, though, each scenario involves the player or players – solo play is possible – attempting to navigate the board's variable terrain in order to find food, water, and shelter, while avoiding various natural hazards. Each player keeps track of his counter's "life level," which measures food and water consumption. The less of each recently consumed, the slower the counter can move. Play is actually quite simple at its base, though there are a number of optional rules that add further "realism" and complexity, should one desire such a thing.

Though I own a copy of Outdoor Survival for "research purposes," I've never actually played it. From what I have gathered online, opinion about its virtues is quite divided, with some viewing it as a straightforward, easy-to-learn introduction to simulation games and others seeing it as dull and tedious. Whatever the truth of the matter, it has a place in the early history of Dungeons & Dragons for the role it played in the conception of wilderness travel. That's not insignificant. If nothing else, it's a reminder that inspiration can come from the unlikeliest of places.

Knights of Camelot Art

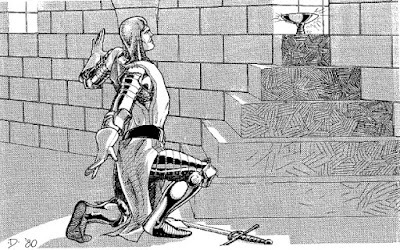

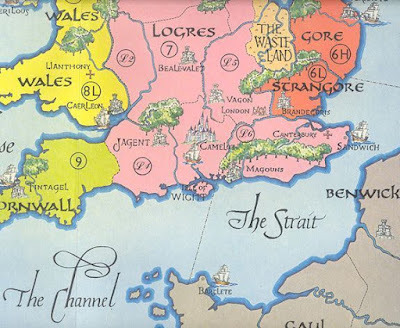

The more I look into TSR's 1980 boardgame, Knights of Camelot, the more entranced I've become by it. Take a look at some of its counters, with art that looks to me like the work of Dave Sutherland:

Mind you, I have an inordinate fondness for counters, so perhaps not everyone will be as impressed as I am. In that case, here are some interior illustrations for your delectation:

Mind you, I have an inordinate fondness for counters, so perhaps not everyone will be as impressed as I am. In that case, here are some interior illustrations for your delectation:

If you're a fan of TSR's artwork from that remarkable period between 1979 and 1982 as I am, this is like catnip. Darlene's map, which serves as the game board, is similarly eye-catching.

If you're a fan of TSR's artwork from that remarkable period between 1979 and 1982 as I am, this is like catnip. Darlene's map, which serves as the game board, is similarly eye-catching.

What a terrific looking game this must have been! I wish I'd seen a copy back when it was originally released. The legends of Arthur and his knights played a huge role in my early introduction to the hobby, so I imagine I would have enjoyed this game as much as I did Greg Stafford's masterful Pendragon.

What a terrific looking game this must have been! I wish I'd seen a copy back when it was originally released. The legends of Arthur and his knights played a huge role in my early introduction to the hobby, so I imagine I would have enjoyed this game as much as I did Greg Stafford's masterful Pendragon.

Thanks, once again, to Thaddeus Moore for providing me with these images.

January 10, 2022

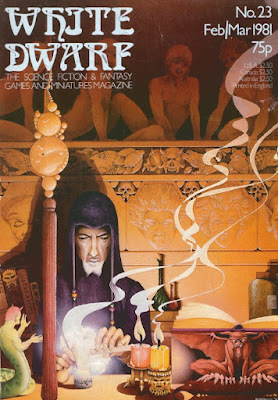

White Dwarf: Issue #23

Issue #23 of White Dwarf (February/March 1981) features a striking cover by Emmanuel, probably best known for the cover of the Fiend Folio. It might well be my favorite cover of the magazine so far and beautifully encapsulates the arcane, almost forbidden quality I strongly associate with the first few years of my involvement in the hobby. Ian Livingstone's editorial is shorter than usual, in which he briefly muses about the possibilities home computers might afford roleplaying gamers in the future. From the vantage point of 2022, it's easy to poke fun at Livingstone's naivete and optimism, but he wasn't wrong to expect that developments in computer technology have an effect on how we play – and indeed conceive of – RPGs.

Issue #23 of White Dwarf (February/March 1981) features a striking cover by Emmanuel, probably best known for the cover of the Fiend Folio. It might well be my favorite cover of the magazine so far and beautifully encapsulates the arcane, almost forbidden quality I strongly associate with the first few years of my involvement in the hobby. Ian Livingstone's editorial is shorter than usual, in which he briefly muses about the possibilities home computers might afford roleplaying gamers in the future. From the vantage point of 2022, it's easy to poke fun at Livingstone's naivete and optimism, but he wasn't wrong to expect that developments in computer technology have an effect on how we play – and indeed conceive of – RPGs."An Introduction to Dungeons & Dragons" by Lewis Pulsipher is the first part of what is described as a series "written for those who have little or no experience of playing" the game. Much like "The Beginner's Guide to Role Playing Games" from the pages of Imagine, I can't help but question the purpose of articles like this. Would anyone utterly unfamiliar with D&D ever buy or read a copy of White Dwarf in order to become better informed about the hobby? Perhaps it was intended to be given to neophytes to read by someone hoping to expand his circle of players?

The first part reads almost like a history – and prehistory! – of Dungeons & Dragons itself, with Pulsipher relating the fact that Dave Arneson had described the activities of his original Blackmoor campaign to him in 1972, long before he had any real understanding of just what was aborning in Minnesota. That Pulsipher highlights the contributions of Arneson is fairly remarkable to my mind, seeing as his was a name that wasn't much spoken in 1981, at least in the circles in which I moved. Pulsipher also states that "D&D is not a pastime for crackpots." He supports this claim by explaining that "one of the designers is in his early 40's, a minister and former insurance executive." Is he referring to Gary Gygax here? Gary would have been 43 at the time of this issue and he did work as an insurance underwriter, but minister? Did I miss something about Gygax's life?

Next up is a lengthy interview with Marc Miller of Game Designers' Workshop. It's a superb interview filled with lots of insights into Traveller – so superb, in fact, that I'll be devoting an entire post to it later this week. "Fiend Factory" continues after the model established a couple of issues back by a series of related monsters and then a scenario that makes use of them. In this case, the monsters are the Flymen by Daniel Collerton, a collection of humanoid houseflies, which I have to admit strikes me as faintly ridiculous. The accompanying adventure, "The Hive of the Hrrr'l," is better than it has any right to be, given the silliness of the monsters. It presents a large, twisting hive of Flymen whose internal conditions are at times quite alien and disorienting to non-insects.

"Open Box" reviews four products, starting with GW's own game, Warlock (8 out of 10). I've always felt somewhat uncomfortable with a publisher reviewing its own releases, but this review seems even-handed and fair. Cults of Prax for Chaosium's RuneQuest and receives a much deserved 10 out of 10, while TSR's Deities & Demigods achieves only 8 out of 10, which I think is generous. The final review of the issue is Leviathan for Traveller (9 out of 10).

"The Elementalist" by Stephen Bland is a new class – a variant magic-user – for use with D&D. As its name suggests, the class specializes in elemental knowledge and magic, including more than two dozen new spells. Not having had the opportunity to use the class in play, I can't speak to how well it stacks up against other classes. Based on reading it, I like it what Bland is attempting to do with it and think it might be a good addition to certain kinds of campaigns. "A Spellcaster's Guide to Arcane Power" by Bill Milne is a proposal for a power point magic system for AD&D. Again, I've not had the chance to use it, but it looks much like one would expect. The only thing about it that caught my eye is that Milne indicates that he modeled it on AD&D's psionics system, something I don't believe anyone has admitted to doing before.

"Khazad-Class Seeker Starship" by Roger E. Moore is a new small craft for use with Ttraveller, described in brief detail, along with a set of deckplans. "Non-Magic Items" describes four unusual but non-magical items for the referee to introduce into his D&D campaign. That sounds more exciting than it is, since three of the four items are simply exotic weapons (and the fourth "item," an odd plant, is there mostly for its damage-dealing capacity). That's too bad, because I'm generally of the mind that most D&D campaigns include too many magical items, even as I recognize the need for providing memorable rewards for the player characters. A collection of truly odd but non-magical items that aren't just weapons would go some way toward alleviating this concern of mine.

Issue #23 is a solid one. I particularly like the increasing presence of Traveller coverage in White Dwarf's pages, as well as its willingness to do things differently than magazines like Dragon. I'm keen to see what the next issue will bring.

Angry Mothers from Heck

My recent post about the second edition of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons proved unexpectedly popular, if the number of comments it generated is any indication. I suppose I underestimated the affection gamers a little bit younger than myself have for the edition, which is quite fascinating in and of itself. As I said, I have no particular fondness for 2e, but I can't bring myself to abominate it the way that some within the old school scene do, in part, because I view it as a very bland edition (or, if I try to be less inflammatory, I might call it mild).

My recent post about the second edition of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons proved unexpectedly popular, if the number of comments it generated is any indication. I suppose I underestimated the affection gamers a little bit younger than myself have for the edition, which is quite fascinating in and of itself. As I said, I have no particular fondness for 2e, but I can't bring myself to abominate it the way that some within the old school scene do, in part, because I view it as a very bland edition (or, if I try to be less inflammatory, I might call it mild).

Some of the more strongly anti-2e commenters reminded me that this mildness took the form of eliminating from the game anything might incur the wrath of, in the words of James M. Ward, "angry mothers from heck." Ward used this amusing turn of phrase in an editorial that appeared in issue #154 of Dragon (February 1990). By this point, I was no longer a subscriber to the magazine and only saw issues irregularly. I don't recall seeing this particular piece until years after it was first published and so it made little impression on me at the time.

In that editorial, Ward explained that

Ever since the Monster Manual came out in 1977, TSR has gotten a letter or two of complaint each week. All too often, such letters were from people who objected to the mention of demons and devils in that game book. One letter each week since the late 1970s adds up to a lot of letters, and I thought a lot about those angry moms. When the AD&D 2nd Edition rules came out, I had the designers and editors delete all mention of demons and devils. The game still has lots of tough monsters, but we now have a few more pleased moms as well.

So, if there's anyone to blame for the removal of demons and devils – not to mention assassins and half-orcs, among other things – it's James M. Ward, who, I assume, was in charge of TSR's RPG division at the time (perhaps someone more knowledgeable about the company's inner workings at the time can shed some light on the subject). Based on what he says here, this was a deliberate choice designed to appease a vocal minority that likely consisted of the same people who also thought the Care Bears were Satanic. He goes on to say that

Avoiding the Angry Mother Syndrome has become a good, basic guideline for all of the designers and editors at TSR, Inc.

Ward elaborates on this shortly afterward, in a paragraph that includes some truly frustrating statements.

TSR prides itself on the quality of the covers and interior art presented in every product. The male and female figures shown are heroic and good looking, and would get either G or PG movie ratings. Our artwork serves to promote the image of high adventure in our games, but it doesn't deal in blood and gore. That isn't the image we want to project.

While I might not be entirely behind the idea that D&D should be G or PG-rated, I can understand TSR's desire to aim for the largest possible audience. There is, after all, a good reason why so few lucrative films are rated R. Even so, the idea that all the art in such a version of Dungeons & Dragons should only depict "heroic and good looking" figures seems downright foolish, if not bizarre. Is it any wonder, then, that those of us introduced into the hobby in the late 1970s or early '80s look on 2e as being esthetically banal?

Ward calls these statements, along with several more specific ones he discusses in his editorial, "a policy statement of TSR, Inc." He further explains that the policy he articulates exists because TSR "care[s] about its products and want as few angry moms as possible." I don't begrudge anyone who thinks well of Second Edition, particularly those who are still having fun with it to this day. That's completely laudable in my opinion and, as I feel I must reiterate, my own feelings toward the edition's rules are far from critical. But, when it comes to 2e's overall esthetics, I'm afraid I'm much more negative in my appraisal, all the more so when I take into account the stated reason why the game's art direction changed so drastically in 1989. How cowardly!

A New Challenge from TSR

One of the things that strikes me about some of the game companies of my youth, like TSR, is how many different games they produced – so many, in fact, that, even a TSR fanboy like myself, couldn't keep up with them all. I owned (and played) most of TSR's RPGs and many of its boardgames, but there were still several that escaped my grasp.

One of the things that strikes me about some of the game companies of my youth, like TSR, is how many different games they produced – so many, in fact, that, even a TSR fanboy like myself, couldn't keep up with them all. I owned (and played) most of TSR's RPGs and many of its boardgames, but there were still several that escaped my grasp.I was reminded of one of them, Knights of Camelot, when I saw this advertisement on the back cover of White Dwarf #22. Was this ad unique to the UK market? If it wasn't, I never saw it prior to this point. Mind you, I never actually saw Knights of Camelot itself outside of the pages of TSR's "Gateway to Adventure" catalog. That's odd, because my local area had excellent distribution of gaming products generally and it was rare that at least one of the game or hobby shops I frequented didn't stock a given product. Judging from the exorbitant prices of used copies of the game, I'm guessing its print run might have been small.

This is a pity. In looking into the game, Knights of Camelot seems quite interesting. For one, it's designed by Glenn and Kenneth Rahman, who are probably best known for another TSR design, Divine Right. For another, it's illustrated by Jeff Dee, Dave Sutherland, Dave LaForce, and includes a map by Darlene that looks quite stunning from the images of it I've seen.

Looks like I have another game to add to my list of white whales …

Looks like I have another game to add to my list of white whales …

January 9, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: Vulthoom

Starting at least with the 1897 H.G. Wells novel, The War of the Worlds – and intensifying after the publication of A Princess of Mars in 1917 – the Red Planet and its inhabitants cane to occupy pride of place in "fantastic" literature of all sorts. Writers as different as Olaf Stapledon, Edmond Hamilton, C.S. Lewis, and Robert E. Howard, among many others, penned Martian tales, each presenting their take on Mars. Even Clark Ashton Smith got in on the act, producing a short cycle of three stories that use the Red Planet as its backdrop.

Starting at least with the 1897 H.G. Wells novel, The War of the Worlds – and intensifying after the publication of A Princess of Mars in 1917 – the Red Planet and its inhabitants cane to occupy pride of place in "fantastic" literature of all sorts. Writers as different as Olaf Stapledon, Edmond Hamilton, C.S. Lewis, and Robert E. Howard, among many others, penned Martian tales, each presenting their take on Mars. Even Clark Ashton Smith got in on the act, producing a short cycle of three stories that use the Red Planet as its backdrop.

As one might expect, Smith's vision of Mars is dark and eldritch, a place of weird horrors and creeping doom. The first Martian tale, "The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis," is one of his most well regarded works and is a good introduction to Smithian Mars, though many prefer the more gruesome "The Dweller in the Gulf." Regardless, both are worthwhile reads and I recommend them without any reservation.

The same cannot be said of "Vulthoom" in my opinion, despite its many fine qualities. First published in the February 1933 issue of Weird Tales, it's a strange conclusion to Smith's Martian stories, in that it's much more straightforwardly adventuresome take on the Red Planet, albeit one with a darker ending than one might have expected in the hands of another writer. Consequently, there are fewer chills than long-time CAS fans might wish, but the central conceit of the story is nevertheless a solid one that almost makes up for its deficiencies in other areas.

The story begins in a way that I think highlights my description of it as "adventuresome."

To a cursory observer, it might have seemed that Bob Haines and Paul Septimus Chanler had little enough in common, other than the predicament of being stranded without funds on an alien world.

Haines, the third assistant pilot of an ether-liner, had been charged with insubordination by his superiors, and had been left behind in Ignarh, the commercial metropolis of Mars, and the port of all space-traffic. The charge against him was wholly a matter of personal spite; but so far, Haines had not succeeded in finding a new berth; and the month's salary paid to him at parting had been devoured with appalling swiftness by the piratic rates of the Tellurian Hotel.

Chanler, a professional writer of interplanetary fiction, had made voyage to Mars to fortify his imaginative talent by a solid groundwork of observation and experience. His money had given out after a few weeks; and fresh supplies, expected from his publisher, had not yet arrived.

The two men, apart from their misfortunes, shared an illimitable curiosity concerning all things Martian. Their thirst for the exotic, their proclivity for wandering into places usually avoided by terrestrials, had drawn them together in spite of obvious differences of temperament and had made them fast friends.

This sounds to me like the beginning of a fairly typical pulp science fiction story of the era, though it does have the advantage of introducing readers quickly to its two protagonists and their predicament on Mars. Haines and Chanler soon encounter a huge example of one of the native Martian – the Aihai – who extends to them an invitation:

"My master summons you," bellowed the colossus. "Your plight is known to him. He will help you liberally, in return for a certain assistance which you can render him. Come with me."

"This sounds peremptory," murmured Haines. "Shall we go? Probably it's some charitable Aihai prince, who has gotten wind of our reduced circumstances. Wonder what the game is?"

"I suggest that we follow the guide," said Chanler, eagerly. "His proposition sounds like the first chapter of a thriller."

The giant Aihai, whose name we later learn is Ta-Vho-Shai, leads the two Earthmen to his master's home, which is located in a forgotten corner of the old city. More than that, it is located underground, which gives Chanler some pause, especially after a long elevator ride deep into the bowels of the planet.

"What do you suppose we've gotten into?" murmured Chanler. "We must be many miles below the surface. I've never heard of anything like this, except in some of the old Aihai myths. This place might be Ravormos, the Martian underworld, where Vulthoom, the evil god, is supposed to lie asleep for a thousand years amid his worshippers."

Overhearing this, Ta-Vho-Shai confirms that his mysterious master is, in fact, Vulthoom. Haines is initially dismissive, suggesting to his comrade a plausible explanation for what the Aihai had said to them.

"I've heard of Vulthoom, too, but he's a mere superstition, like Satan. The up-to-date Martians don't believe in him nowadays; though I have heard that there is still a sort of devil-cult among the pariahs and low-castes. I'll wager that some noble is trying to stage a revolution against the reigning emperor, Cykor, and has established his quarters underground."

"That sounds reasonable," Chanler agreed. "A revolutionist might call himself Vulthoom: the trick would be true to the Aihai psychology. They have a taste for high-sounding metaphors and fantastic titles."

Ta-Vho-Shai takes no further heed of the Earthmen's conversation and leads them into a cavern that is entirely empty but for "a curious tripod of black metal." The tripod bears a block of crystal and, upon it, what appears to be a frozen flower with seven petals – petals that Smith describes as "tongue-like." After a few moments, a voice seems to emanate from the bottom, "a voice incredibly sweet, clear and sonorous, whose tones, perfectly articulate, were neither those of Aihai nor Earthman."

"I, who speak, am the entity known as Vulthoom," said the voice "Be not surprised, or frightened: it is my desire to befriend you in return for a consideration which, I hope, you will not find impossible. First of all, however, I must explain certain matters that perplex you."

The voice then goes on to explain that he is himself an alien to Mars, a traveler from "another universe" whose ether-ship crashed on Mars eons ago. The kings and priests of the planet at that time saw him and the advanced technology he offered as threats to their power. They then spun dark tales about him, claiming he was an interplanetary demon and so, to protect himself, and the Aihai who were attracted to what he offered, he fled beneath the surface of Mars. Vulthoom knows the scientific secret of immortality after a fashion – alternating thousand-year periods of slumber and wakefulness for all eternity – and he offers this freely to those who would help him, such as the Aihai and even Earthmen like Haines and Chanler.

Indeed, this is why he has summoned the two of them to his subterranean refuge.

"I have grown weary of Mars, a senile world that draws near to death; and I wish to establish myself in a younger planet. The Earth would serve my purpose well. Even now, my followers are building the new ether-ship in which I propose to make the voyage."

Vulthoom is forthcoming with information about his plans and the role the two Earthmen will play in his achieving them, but I won't reveal them here. I will only say that they are not wholly to the liking of Haines and Chanler and the remainder of the story concerns their attempts to foil them.

The overall narrative of "Vulthoom" is one I imagine most readers, then and now, will have encountered many times before. Solely on that basis, I can't really recommend the tale. However, Vulthoom himself is a strangely compelling character, as is the concept behind him: an alien being who forms the basis for the Martian version of the Devil. Beyond that, though, what we mostly have is Smith's incomparable prose and that might not be enough to overcome the hackneyed plot of "Vulthoom." Much as I hate to say it, this is not one of Smith's best works; only completists interested in his Mars cycle will find it of lasting value.

January 8, 2022

Fantasy Games on South of Watford

The episode, presented by Ben Elton, is quite well done and offers a solid dose of nostalgia for those of us old enough to remember those times. Among the interviewees are Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson of Games Workshop, as well as Albie Fiore of White Dwarf. The episode is only about 30 minutes long, but it's well worth your time. Take a look when you have the chance.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers