James Maliszewski's Blog, page 2

September 28, 2025

Campaign Updates: Penultimate (Part III)

Grujúng and Nebússa seized their chance. For a fleeting moment, Prince Dhich'uné stood unshielded, his body and mind briefly his own. Grujúng lunged first, his weapon smashing into the prince with a resounding blow that staggered him. Nebússa followed hard on his heels, striking true and drawing another cry of pain.

Grujúng and Nebússa seized their chance. For a fleeting moment, Prince Dhich'uné stood unshielded, his body and mind briefly his own. Grujúng lunged first, his weapon smashing into the prince with a resounding blow that staggered him. Nebússa followed hard on his heels, striking true and drawing another cry of pain. Dhich'uné did not fall. Straightening with dreadful resolve, he rose taller than before, black-green sparks crawling across his flesh, racing to seal the wounds. Behind him, the spectral silhouette that shadowed his form blazed suddenly brighter, swelling until it loomed above him like a giant. With unnatural speed, Dhich'uné lashed out at Grujúng. The strike landed with such force that Grujúng was hurled nearly twenty feet, crashing to the floor in a heap.

From across the bridge, Srüna raised the splendid eye of Krá the Mighty. Its power leapt forth, seizing the prince in an invisible grip. His body convulsed, wracked with fresh agony, yet still he fought on. Gritting his teeth, Grujúng hauled himself upright and staggered back into the fray, standing shoulder to shoulder with Nebússa against their terrible foe.

The prince’s voice thundered across the chamber, low and irresistible: “Come no further! Kneel before Us !” The words reverberated through their bones, laced with a command that was almost impossible to deny. For a heartbeat, their wills buckled, but then, with supreme effort, they pushed back the compulsion. Still, the strain was evident. How much longer could they resist the weight of his power?

As the battle continued across the platform, Kirktá and Keléno stood with their wives, paralyzed by uncertainty. From behind the mask Míru had given him, Kirktá caught sight of something strange. Along the platform’s edges, as though rising from the fathomless chasm below, threads of light began to form like a vast, spiderweb lattice, spreading with unnerving speed. The strands glowed a sickly brown-yellow, racing outward, converging toward Dhich'uné. Were they hunting him of their own accord or answering his silent command? Kirktá could not say and the doubt gnawed at him.

Behind the prince, the towering silhouette still loomed, larger than ever, but Kirktá noticed widening gaps tearing through its form. It strained, like something barely able to hold its grip upon Dhich'uné’s body. The sight brought his thoughts to the talismans Míru had given him. Perhaps the uncut black gem, which he had not thus far used, might prove important somehow.

Keléno, meanwhile, remained steadfast at his side. Shield of defense raised, he sheltered his companions against any unexpected danger. Beyond that, he had no stratagem left to offer, no secret weapon hidden away. All he could do was stand guard and whisper fervent prayers to Lord Sárku, the Five-Headed Lord of Worms, his dread patron and master of the undead.

A stench of rot soon thickened the chamber air. From the platform’s edges, grave worms heaved themselves into view, writhing and crawling toward the fray. Then a voice arose – sepulchral, deep, and resonant enough to shake the stones of the place.

"Apostate! You were mine. Now, you are nothing. Change is the law and you would break it with your false eternity. For this, I cast you out."Through the mask, Kirktá saw a vortex yawning open above Dhich'uné, its pull seizing the shadowy silhouette and dragging it upward, away from his body. The prince shrieked in agony, even as Grujúng and Nebússa pressed their assault, striking at him while the thing within him was torn free.

The worms quickened, swarming closer. At their advance, Dhich'uné recoiled, fear flickering across his face for the first time. While Keléno prayed fervently to Sárku, Kirktá sprinted to the platform’s center. The spectral threads binding the silhouette to the prince had stretched thin, taut and on the edge of breaking. Trusting his intuition, Kirktá drew the uncut black gem. With a swift motion, he slashed through the strands, severing them one by one.

The vortex roared, ripping the last of the shadow from Dhich'uné and devouring it. The prince collapsed, broken and gasping, left to writhe on the platform.

For a moment, silence reigned. Then the voice returned, vast and terrible.

"Do not mistake my hand for friendship. You are tools, no more. The cycle of Change endures. Pray you never draw my gaze again."With those words, Dhich'uné’s still-twitching body convulsed. An unseen force seized him, folding him inward toward a single invisible point. His scream echoed through the chamber and then cut off abruptly as he vanished.

September 27, 2025

Campaign Updates: Penultimate (Part II)

Neither Grujúng nor Nebússa was keen to allow Dhich'uné the opportunity to act any further. They quickly began descending the stairs of the chamber, followed by Srüna. They had no clear plan how to proceed, only that, if allowed too much time to prepare, the Worm Prince would be an even greater threat than he already was. Meanwhile, Keléno made use of a scroll of shield of defense to protect himself, Kirktá, and their wives, Mírsha and Nye'étha, from any ranged attacks that might come from below. Then, they too moved downward toward the center of the chamber, albeit more cautiously than the others.

Neither Grujúng nor Nebússa was keen to allow Dhich'uné the opportunity to act any further. They quickly began descending the stairs of the chamber, followed by Srüna. They had no clear plan how to proceed, only that, if allowed too much time to prepare, the Worm Prince would be an even greater threat than he already was. Meanwhile, Keléno made use of a scroll of shield of defense to protect himself, Kirktá, and their wives, Mírsha and Nye'étha, from any ranged attacks that might come from below. Then, they too moved downward toward the center of the chamber, albeit more cautiously than the others.Dhich'uné took note of the rapid descent of Grujúng, Nebússa, and Srüna, shouting to Kirktá, "Call off your attack animals or I shall be forced to do so myself – and I will not be as gentle as you would be, brother." Upon hearing that, the trio slowed their movement but did not stop completely. Seemingly satisfied, Dhich'uné explained, "Once, I believed I must sit upon the Petal Throne only to die, my blood poured out under a knife wielded by you, in order to seal a new pact with the One Other. I now know that was folly. So crude a sacrifice was never required. Not blood, nor flesh – only preparation.”

At this, Kirktá and then the others noticed that Dhich'uné's body was surrounded by a black-green silhouette, like another version of himself, only larger and that seemed to fade in and out of sight. Kirktá, still under the effects of the seeing other planes spell he'd cast in the previous room, also saw something else. This silhouette was wrapped around Dhich'uné's limbs and head, pulling at them and perhaps even controlling him. It was as if there were a hidden puppeteer at work. The silhouette possessed moments of iridescence, along with gaps in its strange substance. The gaps looked like holes in worn cloth, with only "strands" connecting it to Dhich'uné in places.

Dhich'uné continued,

“Years I gave to Sárku, years hollowing myself of every weakness, every desire, even of life itself. I thought I was to become his vessel, his undying emperor. But no: all that time, I was shaping myself for another, greater patron. The One Other has chosen me not as sacrifice but as a partner. Together, we shall reign without end. The empire eternal. The dream perfected. Tsolyánu unchanging.”

Needless to say, this admission terrified the characters. They suspected that Dhich'uné had altered his original plans and now had some new scheme in mind. Yet they never once suspected that he might abandon Lord Sárku, the god to whom he had dedicated his life up to this point, and seek to join rather than control the One Other, with the pariah god as his eternal co-ruler over Tsolyánu. More than ever, they knew he had to be defeated.

Grujúng and Nebússa crossed one of the bridges leading to the central platform where Dhich'uné stood. They were still about 50' from him, just about within sprinting range. Srüna stayed on the other side of the bridge, her splendid eye of Krá the Mighty at the ready. Kirktá and the others similarly stayed on the far side of the chasm separating the platform from the ground floor of the chamber. From there, it was obvious that the large circular object near Dhich'uné was likely the prison of the One Other, now open. The characters had seen it in one of the "windows" they encountered earlier in Avanthár, windows that looked to reveal the future or perhaps possible futures.Kirktá then put on the mask he had been given by Míru, the mysterious priest of the One Other who had inexplicably aided him in recent weeks. The mask revealed yet more about the strange silhouette that surrounded Dhich'uné, in particular that it was simultaneously growing in strength and intensity but also straining against its connection to the Worm Prince's mortal form. The holes seen earlier were larger now, even as the silhouette looked more potent than ever.Dhich'uné yelled out, “I — We — have surpassed all need for the old ways. This new pact is stronger, perfected. They bound Us , long ago, in chains of memory. But all chains rust, all chains break.” Every time Dhich'uné spoke, another voice reverberated under his own, becoming stronger and louder. Whenever he attempted to say "I" or "me," another voice drowned him out, saying "we" or "us" in a voice filled with fury and hatred. “They shall pay. They shall all pay. The First Tlakotáni stole Our freedom and now thinks We will be satisfied with its mere restoration. No, his descendants have fattened on Our silence. Now We break that silence. Now We will break all!”

Yet, something of Dhich'uné's own ego and arrogance remained. Doubled over in pain, grabbing his head, he wrestled with the One Other's increasing control, “No! Not destroy. Preserve! Rule forever! Eternal Tsolyánu. Eternal throne. I — We — I —” Dhich'uné's body was now wracked with pain and contorted in unnatural ways. Black-green sparks of otherplanar energy snaked across him. “Enough! We are no emperor’s slave. We are no ornament for the Petal Throne. We are vengeance unquenched! Rivers will boil, temples will sink, streets will drown in silence. We will unmake this empire of thieves. We will bind this land as it once bound Us !”

Now on his knees, Dhich'uné extended his hand in the direction of Kirktá, his face and his voice, for a brief moment, solely his own, "Brother, end it ..."

September 26, 2025

Campaign Updates: Penultimate (Part I)

As I briefly stated yesterday, my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign had its penultimate session yesterday – penultimate, not ultimate. The final session will, in fact, be next week, as we try to wrap up (to the extent that it's possible after more than ten and a half years of regular play) the remaining threads of the Tsolyáni succession crisis and incipient civil war. That's probably as good a point as any to end the campaign. After the heights of imperial power politics and the cosmic threat of a pariah god, I'm not certain there's anywhere for House of Worms to go but down. Better to end on a high note. Plus, the truth is, after more than a decade, we're all a little tired and could probably use a change of scenery, so to speak, even if I'm still unsure that the campaign begun in its wake could ever live up to this one.

The characters had, for several sessions, been working their way through the bowels of Avanthár, the seat of Tsolyáni power north of the capital city of Béy Sü. Avanthár is often called a "citadel" and it is, but it's also a very ancient military installation dating back to before the Time of Darkness. It's filled with millennia's worth of technological and magical defenses intended to impede anyone's attempts to infiltrate it. Consequently, the characters had their work cut out for them, as they contended with all manner of unexpected and deadly wards, traps, and obstacles. Fortunately, they'd been aided by Prince Táksuru, one of the contenders for the Petal Throne, who provided them with certain aids in their quest. Likewise, Kirktá had been gifted with several artifacts by Míru, a servant of the One Other posing as a priest of Belkhánu. Like the First Tlakotáni, he wanted to see the pariah god freed from captivity beneath Avanthár.

The characters knew that Prince Dhich'uné was already ahead of them, making his way to the prison of the One Other, in hopes of establishing a new pact with the god. How he intended to do this was uncertain, since, so far as they understood things, Dhich'uné needed to be emperor before he could offer his spirit-soul to the One Other in exchange for eternal rule over Tsolyánu. Clearly, he had some kind of back-up plan or alternative scheme, one that didn't require either his victory in the Kólumejàlim or the involvement of Kirktá, who had been trained in his youth for the purpose of aiding Dhich'uné in his goals – or so he said at any rate.

Moving expeditiously from the last room they had explored, they came across a set of sliding doors that looked as if they had been partially forced open. Strange black-green fungus covered part of the door and had begun to slowly spread into the one where the characters now were. Peering into the next room, Nebússa and Kirktá could see that it was a large, circular chamber. The fungus was everywhere within. Along the curve of one wall, there was an opening, like a door. A large "plug" made of the strange ceramic/metal material of the Ancients lay shattered on the ground. The plug was covered in strange symbols and was slowly breaking down. Under the effects of the seeing other planes spell, Kirktá saw a strange creature whose shape constantly shifted forms – one minute an insect, another a reptile, another a cephalopod, and so on – smashing up the bits of the plug.

Grujúng felt the time to act was now. He leapt into the room, weapon drawn. His appearance drew the attention of the creature, which flew/crawled/ran toward him, shifting between its various forms. He could not see it, however; its otherplanar nature made it largely invisible to normal sight. Nevertheless, as he felt its presence, he swung at it with his enchanted blade, striking it. For a moment, it phased into existence before disappearing again. Nebússa joined him, followed by his wife, Srüna. Soon, the other characters joined them. Nebússa, using the sword of the Ancients he acquired some time ago, likewise struck at the beast. Srüna, however, cast a spell of paralysis, which – surprisingly – worked, freezing the creature in place. The others then made short work of it. Upon its destruction, it faded away, as if it had never existed.

From the open portal once blocked by the plug, the characters could see more black-green fungus and flashes of similarly colored light. They made their way toward the opening and looked inside. There they saw another immense room, arranged like an amphitheater made of the same ceramic/metal material as the plug. Arrayed around the topmost level of the amphitheater were large statues depicting human figures in metal armor of a sort that reminded the characters of the Ru'ún, the artificial servants of the Ancients. At the bottom of the amphitheater was a circular platform, perhaps 100' across, separated from the floor by a 20'-wide chasm. Four bridges enabled passage from the floor to the platform, upon which rested a large circular object with a door on its side. The door was wide open and a robed figured stood beside it.Upon seeing the characters, the figure called out in a loud voice, "You have come too late, brother. I have seen the truth."

September 25, 2025

Dhich'uné is Dead

The penultimate session of the House of Worms campaign wrapped just minutes ago, with the defeat of Prince Dhich'uné within the bowels of Avanthár. Next week will see the campaign conclude after ten and a half years.

I'll do a fuller write-up of today's events later, but I felt the need to share this momentous occasion.Dhich'une is Dead

The penultimate session of the House of Worms campaign wrapped just minutes ago, with the defeat of Prince Dhich'uné within the bowels of Avanthár. Next week will see the campaign conclude after ten and a half years.

I'll do a fuller write-up of today's events later, but I felt the need to share this momentous occasion.September 24, 2025

Retrospective on Retrospective

Retrospective on Retrospective by James Maliszewski

Thoughts on Another Popular Feature

Read on SubstackSeptember 23, 2025

Retrospective: Vikings Campaign Sourcebook

Perhaps it's simply a facet of my getting older that I can now look back on AD&D Second Edition with a lot more equanimity than I once did. Mind you, I've been traveling this particular road for some time now, but, lately, I've found myself thinking ever more fondly of 2e, which I know is heresy in certain old school circles. Earlier in this blog's existence, I accepted without question the received wisdom that Second Edition heralded AD&D's decline. After all, it was the edition that promoted railroad-y adventure design, unnecessary rules complexity, and an endless parade of splatbooks. There’s some truth to those criticisms, but, as is often the case, the reality is more complicated. As I mellow in my old age, I’ve been struck by just how many interesting, even innovative, things TSR attempted under the 2e banner, even if not all of them succeeded.

One of the best examples of this spirit of experimentation is the Historical Reference (HR) series, the so-called “green books” published between 1991 and 1994. These seven volumes attempted to show that AD&D 2e could serve as a kind of universal fantasy engine, capable of handling settings well outside the game’s usual mold. Importantly, they weren’t intended as dry exercises in historical simulation. Instead, they leaned into a blend of history, legend, and myth, presenting material grounded in real cultures but always leavened with enough fantastical elements to remain recognizably D&D.

The first entry, the Vikings Campaign Sourcebook (1991), written by 2e’s chief architect, David “Zeb” Cook, set the tone for what followed. Vikings had been part of D&D’s DNA from the beginning. Deities & Demigods included Odin, Thor, and Loki, while Gygax’s Appendix N highlighted Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword, a novel steeped in Norse myth and heroic fatalism. Cook was tapping into a deep well already familiar to most players and the Vikings Campaign Sourcebook offers Dungeon Masters and players alike a toolkit for adventures inspired by the Viking Age.

The book begins with a broad overview of Norse society (law, honor, family, and daily life) along with a timeline of major events between the years 800 and 1100. Cook wisely avoids the caricature of Vikings as nothing more than berserk raiders, instead presenting them also as explorers, traders, and settlers. This emphasis on cultural breadth is, in fact, one of the book’s strengths and I find I appreciate that aspect of it even more now than I did when I first read it.

Character options include modifications to the standard AD&D classes, along with two entirely new ones, the berserker and the runecaster. It’s an odd choice to present these as separate classes rather than kits, especially since The Complete Fighter’s Handbook (released a couple of years previously) had already popularized kits as the preferred method for customizing characters. Whether this was simply Cook experimenting with format or an editorial decision from TSR is unclear, but it does highlight how much the HR series was still finding its footing. Additional rules cover equipment, magic items, and monsters, many of the latter being existing AD&D creatures modified to fit Norse myth more closely.

One of the book’s most enjoyable sections is its gazetteer of the Viking world, which is simply medieval Europe as seen through the eyes of the Norse. This is accompanied by a full-color foldout map, a TSR flourish I’ve always appreciated. In fact, I find this gazetteer and map more immediately inspiring than some of the book’s rules material, though that says as much about my own tastes as it does about Cook’s writing.

It must be said, though, that the Vikings Campaign Sourcebook is not an in-depth exploration of Norse history or culture. It was never meant to be. At 96 pages, it can only sketch the outlines of the period, leaving the DM and players to fill in the gaps with their own research or imagination. In that sense, it succeeds more as a primer or springboard than as a comprehensive treatment of its subject.

Despite this, the book plays well to AD&D’s inherent strengths. Heroism, exploration, and myth were already central to the game’s ethos and Cook’s presentation provides just enough historical texture to make a Viking campaign feel distinctive without drowning it in pedantry. For all its limitations, the result is a supplement that feels genuinely usable at the table.

Re-reading it now, I’m struck by how emblematic it is of TSR’s adventurousness during the 2e era. This was the same period that produced not only the Complete Handbook series and the later Option books, but also settings as varied as Dark Sun, Spelljammer, and Al-Qadim. The HR series was part of this broader impulse to push beyond “generic fantasy” and explore what else AD&D could do. The Vikings Campaign Sourcebook may not have been perfect, but it was ambitious and I think that matters.

More than three decades later, the Vikings Campaign Sourcebook deserves to be remembered not just as a curiosity but as evidence that AD&D Second Edition was more interesting and more daring than its detractors usually allow. Mechanically, it has many flaws, but it also captures something essential about both D&D and the Norse material it adapts, namely, the thrill of stepping into a world where myth and history intertwine and where characters stand larger than life. For Dungeon Masters curious about running Viking adventures (or simply looking to mine inspiration) Cook’s book still has much to recommend it, as do all the books in the HR-series.September 22, 2025

REPOST: The Articles of Dragon: "Of Grizzly Bears and Chimpanzees"

As I've said innumerable times on this blog, in my heart of hearts, I'm really more of a science fiction fan than a fantasy one. That's why, much as I love D&D, I'm perpetually pining for the opportunity to play a sci-fi RPG. In my younger days, I had a slew of SF games I'd pull out to play whenever my friends and I decided we were tired of D&D. One of the most popular was

Gamma World

, which some would no doubt call a science fantasy game (and, to be fair, that's how its first edition bills itself), but I don't think that alters my essential point, namely that, when I wasn't playing D&D, my first inclination was to pull out a science fiction-y game like Gamma World or Traveller or the FASA version of Star Trek.

As I've said innumerable times on this blog, in my heart of hearts, I'm really more of a science fiction fan than a fantasy one. That's why, much as I love D&D, I'm perpetually pining for the opportunity to play a sci-fi RPG. In my younger days, I had a slew of SF games I'd pull out to play whenever my friends and I decided we were tired of D&D. One of the most popular was

Gamma World

, which some would no doubt call a science fantasy game (and, to be fair, that's how its first edition bills itself), but I don't think that alters my essential point, namely that, when I wasn't playing D&D, my first inclination was to pull out a science fiction-y game like Gamma World or Traveller or the FASA version of Star Trek.Consequently, I loved "The Ares Section" of Dragon, whose articles, even when they weren't of immediate use to me (like the articles on, say, Universe ). Among my favorites, though, were the Gamma World articles by John M. Maxstadt, which I often did use in my games. A good example is "Of Grizzly Bears and Chimpanzees," which appeared in issue #89 (September 1984). As its name suggests, the article is devoted to detailing the unique abilities of animals, in this case as stock for mutated animal PCs. Maxstadt provides some basic statistics for a dozen different animal types -- bears, big cats, herbivorous animals, primates, snakes, and birds. These statistics include things like general size, their ability to vocalize and grasp/carry items, in addition to more obvious game stats like armor class and movement rates. The idea behind the article is to rationalize the abilities of mutated animals both from a game mechanical and a logical perspective, thereby making them more attractive to play and easier for the referee to accommodate.

Looking back on the article now, what's fascinating is how simple it really is in the end. There are a couple of pages of game stats, presented as Monster Manual-like entries, followed by a couple of pages of explanation of what the stats mean and how they interact with other aspects of the Gamma World rules. That's probably why I found them so easy to use. At the same time, they carry with them an implicit vision of Gamma World, one that's a bit more limited than the wide open "wahoo!" style usually associated with the game. Maxstadt, for example, doesn't provide stats for insects or amphibians, so the referee is either left to his own devices in coming up with his own or else disallowing such mutated animal types, as Maxstadt apparently did. Now, there's nothing wrong with such a limitation and indeed there's definitely a case to be made for it, but, somehow, the idea of playing Gamma World with any limitations seems to go against its fundamental grain and, were I ever to run a campaign again, I'd probably not use this article's system or else come up with additional stats for other types of animals.

The Fall

As I've noted before, Fall is without question my favorite season of the year. This has always been true, though I suspect that, when I was younger, the fact that my birthday is in October might have played a role in this. Nowadays, I find it’s more a consequence of the cooler weather – I’ve never been fond of heat and humidity, despite growing up in the Baltimore area – and the vibrant colors of the leaves. I look forward to seeing them start to turn in September. It’s one of Nature’s most beautiful displays, a yearly pageant that transforms even familiar streets and landscapes into places of wonder. The reds, oranges, and yellows mingle in shifting patterns and I often catch myself lingering on walks or staring out the window longer than I intend just to take it in.

Along with the colors comes the crispness of the air, the subtle smell of woodsmoke, and that hushed anticipation before the onset of Winter. Fall feels like both an ending and a beginning, a reminder of time’s passage, yet also of its cycles. It never fails to lift my spirits and sharpen my thoughts, which is why, year after year, it remains the season I cherish most.

The older I get, the more Fall takes on a new weight. The turning of the leaves is not just beautiful; it is also a reminder of impermanence. Those brilliant colors I love so much exist only because the trees are preparing for Winter’s barrenness. Their beauty is inseparable from their decline. That duality has become harder to ignore with each passing year, not because it depresses me, but because it feels increasingly familiar.

I notice my own changes. There are the small, physical reminders – a few more creaks in the body than there used to be – but also the larger ones, like the deaths of friends and family, the slow realization that there are fewer years ahead than behind. Like Fall itself, this is simultaneously melancholy and strangely reassuring. The season feels like a mirror of my inner life, a yearly confirmation that endings are natural, inevitable, and not without their own beauty.

I feel this most keenly in my roleplaying. The House of Worms campaign, which I once seriously imagined might go on forever, is now drawing to a close. Indeed, its end may come as early as this week. Characters who once lived vividly in weekly sessions will soon exist only in memory, stories recounted later or preserved in old notes. There’s a bittersweetness in realizing that even my longest-running campaign is subject to the same fate as all the others. But then, isn’t that part of what makes them precious?

If campaigns never ended, if characters never retired or died, would we hold their adventures in the same regard? I increasingly doubt it. It is precisely because they do end that we remember them with fondness. Their impermanence is what gives them weight. The knowledge that we only get so many sessions together makes each one feel more valuable.

The same is true of writing. Projects that once consumed me eventually reach their conclusion, whether by being finished, abandoned, or transformed into something else. For a long time, I resisted this reality. I held on to drafts and half-formed ideas as if they could be made immortal through sheer persistence. Letting go felt like failure. Now, though, I see it differently. Letting go is its own discipline and every ending clears space for something new. The cycle continues, just as surely as Fall gives way to Winter and then to Spring again.

What strikes me most is that endings, whether in life, roleplaying, or writing, are not failures. They are simply part of the pattern. Recognizing this has changed how I approach my creative work. I don't worry about whether a campaign will last or whether a project will ever be finished in some definitive sense. Instead, I try to enjoy the process, knowing that all things, however beloved, eventually end. Far from diminishing their value, this makes the time spent with them more meaningful.

That's why Fall has become more than just my favorite season. It’s also become a yearly reminder that beauty and impermanence are intertwined, that endings are inseparable from beginnings, and that what matters most is what we do while the colorful leaves still cling to the branches.September 21, 2025

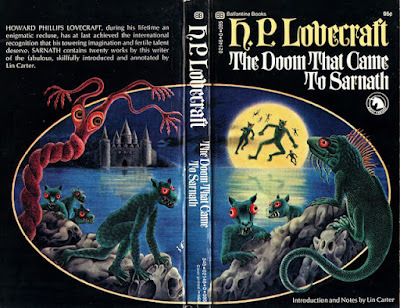

REPOST: Pulp Fantasy Library: The Doom That Came to Sarnath

The early part of H.P. Lovectaft's literary career is marked by the influence of the Anglo-Irish author, Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron Dunsany, better known to posterity simply as Lord Dunsany. Between 1905 and 1919, Dunsany wrote numerous short stories that are set in a fictional world, Pegāna, with its own imaginary history and geography. These stories laid much of the groundwork for the evolution of the nascent genre of fantasy into what we know today (without which the hobby of roleplaying would likely not have been possible).

The early part of H.P. Lovectaft's literary career is marked by the influence of the Anglo-Irish author, Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron Dunsany, better known to posterity simply as Lord Dunsany. Between 1905 and 1919, Dunsany wrote numerous short stories that are set in a fictional world, Pegāna, with its own imaginary history and geography. These stories laid much of the groundwork for the evolution of the nascent genre of fantasy into what we know today (without which the hobby of roleplaying would likely not have been possible). Nowadays, Lovecraft's Dunsanian period tends to be overlooked, particularly by those enamored of his later, more famous tales of the "Cthulhu Mythos" (itself a term never employed by HPL himself). To the extent that these earlier stories are remembered, they're often mistakenly taken to be part of his "Dream Cycle." To some extent, Lovecraft himself is to blame for this misapprehension, because of the allusions and references he makes to his Dunsanian tales in works like The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath. Likewise, Lovecraft's admirers have, as ardent fans so often do, attempted to impose upon his canon clear divisions whereby a work belongs in one category or another, despite the evidence that Lovecraft himself was far less rigid in his own thinking.

"The Doom That Came to Sarnath" is a good example of this phenomenon. Originally published in the June 1920 issue of the amateur fiction periodical, The Scot, the story was widely reprinted after Lovecraft's death, starting with the June 1938 issue of Weird Tales. Since I was unable to find an image of the issue of The Scot in which it premiered to accompany this post, I opted instead for the terrific cover of the 1971 Ballantine Adult Fantasy edition, painted by Gervasio Gallardo. My own introduction to the story came in the 1982 Del Rey collection of the same name with a cover by Michael Whelan, but I think I like the Gallardo version better.

The story begins in a way that makes clear Lovecraft's intentions:

There is in the land of Mnar a vast still lake that is fed by no stream and out of which no stream flows. Ten thousand years ago there stood by its shore the mighty city of Sarnath, but Sarnath stands there no more.

As I read it, "The Doom That Came to Sarnath" is a myth or legend coming down to us from the distant past, as Lovecraft implies immediately thereafter:

It is told that in the immemorial years when the world was young, before ever the men of Sarnath came to the land of Mnar, another city stood beside the lake; the grey stone city of Ib, which was old as the lake itself, and peopled with beings not pleasing to behold.

The story is filled with phrases like "when the world was young" that suggest to me at least that the reader isn't to understand the tale he tells as taking place in an imaginary or dream land but instead in the ancient and forgotten past of our own world, though, as we shall soon see, the matter is not cut and dried. Regardless, Lovecraft establishes that the beings of Ib were "in hue as green as the lake and the mists that rise above it" and "they had bulging eyes, pouting, flabby lips, and curious ears, and were without voice." One of the reasons I chose the cover above is because it features Gallardo's interpretation of what the beings of Ib looked like.

In time, men to the land of Mnar and founded the city of Sarnath. They marveled at the sight of the beings Ib.

But with their marvelling was mixed hate, for they thought it not meet that beings of such aspect should walk about the world of men at dusk. Nor did they like the strange sculptures upon the grey monoliths of Ib, for those sculptures were terrible with great antiquity. Why the beings and the sculptures lingered so late in the world, even until the coming of men, none can tell; unless it was because the land of Mnar is very still, and remote from most other lands both of waking and of dream.

The hatred of the men of Sarnath grew and, in time, resulted in a war in which all of the beings of Ib were slain and their "queer bodies [pushed] into the lake with long spears, because they did not wish to touch them." The men of Sarnath likewise toppled the monoliths of Ib and cast them into the lake. The only evidence of Ib the men kept was

the sea-green stone idol chiselled in the likeness of Bokrug, the water-lizard. This the young warriors took back with them to Sarnath as a symbol of conquest over the old gods and beings of Ib, and a sign of leadership in Mnar.

The men placed the idol in one of their own temples, but, on the following night,

a terrible thing must have happened, for weird lights were seen over the lake, and in the morning the people found the idol gone, and the high-priest Taran-Ish lying dead, as from some fear unspeakable. And before he died, Taran-Ish had scrawled upon the altar of chrysolite with coarse shaky strokes the sign of DOOM.

The story's titular doom does not come quickly and Lovecraft spends the remainder of the story describing the next thousand years of Sarnath's history, as it grows in power – and pride – within the land of Mnar, eventually becoming the capital of a mighty empire founded on hate and greed. Lovecraft presents these facts in a way that seemingly implies admiration of Sarnath and its glory, but it soon becomes clear that this is a mask for condemnation of its excesses and, by the end, Sarnath and its people pay the price for their past sins.

To call "The Doom That Came to Sarnath" a morality tale is probably simplistic. At the same time, Lovecraft is not at all subtle in his connecting the destruction of Ib with the later doom that befalls Sarnath. In any case, the story is luxuriously written, redolent with adjective-laden description that reminds a bit of Clark Ashton Smith, though utterly lacking in his black humor. Its almost Biblical rhythms and cadences practically demand that the story be read aloud. In the grand scheme of things, it's one of Lovecraft's minor works but it's nevertheless a successful one for which I have a strange affection.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers