James Maliszewski's Blog, page 5

September 4, 2025

Dream-Quest: Knight of Dreams

Elsewhere, I'm still developing Dream-Quest, my Lovecraftian/Dunsanian fantasy game based on Old School Essentials. This is a side project to the others I'm already sharing over at Grognardia Games Direct, but it's starting to pick up steam, with the goal of playtesting an early version of it in the winter. In the meantime, I'm filling out the roster of character classes for play, with the Knight of Dreams being the latest one. The class takes loose inspiration from the knights who serve King Kuranes in Lovecraft's "Celephaïs."

September 3, 2025

Short-Term

As you know, I'm currently refereeing three different roleplaying game campaigns: House of Worms (Empire of the Petal Throne), Barrett's Raiders (Twilight: 2000), and Dolmenwood (which doesn't have a separate name, despite my long-held practice of bestowing them). Dolmenwood is the newest of the three, having been started a little less than a year ago (November 2024), while the other two of much older vintage – House of Worms has been going for over a decade of continuous play, while Barrett's Raiders will celebrate its fourth anniversary this December.

Though I never specifically set out to run a multi-year campaign when I began any of these, I nevertheless hoped that they would last for several years. Indeed, it remains my firm belief that roleplaying games are best enjoyed not as some casual entertainment but as something demanding more sustained commitment from both players and the referee. This is, in my opinion, the ideal form of roleplaying, for reasons I've elucidated elsewhere. Consequently, I always feel a little bit defeated when a new campaign doesn't quite take and sputters out after only a few weeks or months.

Of course, if I look back at the more than four decades I've been involved in this hobby, I can see far more "failed" campaigns, which is to say, campaigns lasting a year or less, than those lasting two or more years, never mind a decade. House of Worms is truly unique. Were I to live to be one hundred, I doubt I will ever strike gold the way I have with House of Worms. Even after all this time, its longevity is inexplicable to me – a one-of-a-kind coincidence of elements that I couldn't have planned no matter how hard I tried (and I didn't). As that campaign prepares for its conclusion, I cannot help but be profoundly grateful for the experience of such a long and enjoyable campaign.

I bring all this up as something of a prolog to a conversation I recently had with my adult daughter, who's a bit more plugged into the contemporary RPG scene than I am. We were out somewhere and I saw a new roleplaying game with which I wasn't familiar. I thought the idea behind it was interesting but very focused. I told her that I couldn't imagine anyone being able to play this game for very long, to which she replied, "Not everyone wants to play the same game continuously for years."

Now, obviously, I knew this to be true. Even so, hearing her say that made me ponder the question a bit more. How many of the games I own are broad enough in concept that I can imagine playing them for years? The truth is fewer than I would have thought. Certainly, Dungeons & Dragons and its various descendants have proved that they can support long-term play. I don't hesitate in saying that about Traveller as well, but what about, say, Call of Cthulhu? Is it possible to play a continuous CoC campaign for years with the same group of characters (more or less)? I know of long-running Call of Cthulhu campaigns but how common are they and are the odds stacked against them, given the frame of the game?

Mind you, I'd argue that the odds are stacked against most RPGs, not necessarily because of their rules or even their focus but because most players and referees grow bored of them after a while. Gamer ADD is a real thing and always has been, though I think it's gotten worse in the last couple of decades. If I had to venture a guess as to why, I think its roots are twofold. First, I think most people nowadays are much more easily distracted. There are so many shiny things competing for their attention that it's harder and harder to keep them on task. Second, there are so many more RPGs to choose from. Gamers have always been prone to neophilia in my experience, so when there are literally dozens of new games released every year, it's little wonder that they find it difficult to commit to any one of them for more than a few weeks or months. They wouldn't want to "miss out," would they?

My daughter is more charitable than I. She compares many gamers' approaches to a charcuterie board. They want a little of this and a little of that but aren't willing to make an entire meal out of salami. Instead, they want to sample everything. That's fair, I suppose, and I can't really be too critical of this perspective, because, at various times, I've adopted something close to it myself. Still, it's another reminder that my tastes and preferences are increasingly out of touch with what the hobby seems to be about. I guess that's just the nature of getting old.The Origins of Grognardia

September 2, 2025

Retrospective: Rifts

As I edge into my elder years, I’m struck by how persistent one theme has been across the more than half-century of my life: The End of It All. Popular culture has long carried the conviction that, for all our technological advances and sophistication, civilization was always teetering on the brink of catastrophe. Ice ages, global warming, acid rain, killer bees, the Jupiter Effect (remember that?), alien invasions, nuclear war –again and again we were told humanity is on a one-way trip to ruin. This apocalyptic sensibility seeped into everything: books, movies, television, even roleplaying games.

As I edge into my elder years, I’m struck by how persistent one theme has been across the more than half-century of my life: The End of It All. Popular culture has long carried the conviction that, for all our technological advances and sophistication, civilization was always teetering on the brink of catastrophe. Ice ages, global warming, acid rain, killer bees, the Jupiter Effect (remember that?), alien invasions, nuclear war –again and again we were told humanity is on a one-way trip to ruin. This apocalyptic sensibility seeped into everything: books, movies, television, even roleplaying games.Deeper considerations aside, it's easy to understand why: apocalypses offer unique opportunities for adventure. The breakdown of the old order creates lots of space for heroes and villains who make their own rules, just as ruined cities are the perfect places for such people to loot and explore. The post-apocalyptic world might not be a great place to live, but it often sounds like a great place to play an RPG, filled as it is with danger, mystery, and the promise of carving out something new amidst the wreckage of the old.

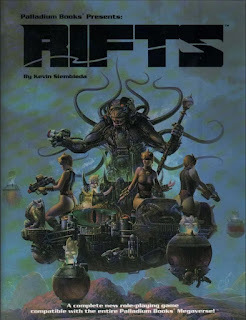

Over the years, there have been many post-apocalyptic RPGs, some of which I’ve greatly enjoyed. As readers know, I’m currently refereeing Barrett’s Raiders, my ongoing Twilight: 2000 campaign, so it’s a genre that has long appealed to me. That’s why, when Palladium Books released its own entry into the field, Rifts, in 1990, I took notice. Written by Kevin Siembieda, like most of Palladium’s output, the game now feels like the perfect encapsulation of its era’s RPG culture: exuberant, excessive, self-confident, and utterly unconcerned with its own contradictions. Even more than three decades later, Rifts remains both instantly recognizable and difficult to pin down. To call it merely a “post-apocalyptic” RPG misses the mark, because Rifts was (intentionally) never just one thing. It was a collision of genres and ideas – science fiction, fantasy, horror, superheroes – whose very incoherence was what made it so compelling.

At the time of its initial release, I was already familiar with Palladium through a few of the company's earlier releases, thanks in large part to my college roommate, who was a fan. Consequently, I wasn't surprised when I saw a big rulebook filled with evocative, comic-style artwork and Siembieda’s signature blend of dense rules and poor organization. What I wasn’t prepared for was the scope of its setting. Here was Earth, centuries after a magical cataclysm tore open rifts in space and time, unleashing every kind of horror, wonder, and menace imaginable. Dragons and demons rubbed shoulders with cyborg mercenaries, mutant animals, and alien warlords. The North American continent was a patchwork of techno-dystopias, barbarian kingdoms, and wildernesses haunted by supernatural predators. Almost anything was possible in Rift by design, since one of its purposes was to provide a setting where elements from other Palladium games could be dropped in easily.

The original rulebook – the only one I ever saw – had a clear appeal. Its black-and-white illustrations (by artists like Kevin Long and Siembieda himself) were part of its appeal. Likewise, its cover painting by Keith Parkinson immediately communicated the tone of Rifts: over-the-top, bombastic, and larger than life. Rifts didn’t just allow for power fantasies; it practically demanded them. Whereas Dungeons & Dragons offered a gradual "zero to hero" style of advancement, Rifts lets you begin the game as a cyber-knight, a near-invulnerable walking tank, or a ley line–powered sorcerer who can bend reality.

That excess was both the game’s great strength and its great weakness. The rules were built on the already creaky Palladium system, with its notorious combination of percentile skills, mega-damage mechanics, and endless lists of powers, spells, and combat options, not to mention character classes. "Balance" of any kind is effectively nonexistent. A city rat with a pistol could be in the same party as a dragon hatchling with spellcasting and mega-damage claws, but the game's overall approach was, more or less, that Game Master can make it all work somehow. Honestly, that's not necessarily terrible advice, though I'm sure it wouldn't satisfy many gamers, especially nowadays.

Looking back, Rifts is a fascinating snapshot of where the hobby was at the time. By 1990, D&D had already begun its transformation into an ever more baroque monstrosity with a plethora of options and settings, while White Wolf was just about to launch its World of Darkness storytelling games, forever changing the face of the hobby. Rifts, by contrast, reveled in excess, giving players the keys to the toy store and daring them to see what happened. The result was chaotic, but, based on what longtime fans tell me, immensely fun. In the years that followed, the flood of supplements, world books, and sourcebooks only expanded the game’s already immense scope, making it simultaneously baffling to outsiders but also exactly what its fans wanted.

Rifts will never win any awards for being elegant or balanced, but, speaking largely as a disinterested party, I think it largely succeeds on its own terms. It offers a vision of roleplaying that is anarchic, imaginative, and gloriously insane. For many in 1990, Rifts was a passport to a multiverse where every idea anyone ever had from comics, cartoons, or science fiction could live side by side. That’s no small achievement, even if it's not for everyone, myself included.September 1, 2025

REPOST: The Articles of Dragon: "Before the Dark Years"

While the way that TSR looted the corpse of SPI was shameful (and likely had a deleterious effect on the wider hobby), it had one positive effect from the perspective of my youth: the advent of the "Ares Section" of Dragon. I've always been more of a sci-fi fan than a fantasy one, so knowing that every issue of Dragon would devote two or three articles to the genre each month was a good thing in my view. (This also probably explains why the issues of Dragon I was most fond of ran from 80s to the early 100s – corresponding very closely to the lifespan of the Ares Section).

While the way that TSR looted the corpse of SPI was shameful (and likely had a deleterious effect on the wider hobby), it had one positive effect from the perspective of my youth: the advent of the "Ares Section" of Dragon. I've always been more of a sci-fi fan than a fantasy one, so knowing that every issue of Dragon would devote two or three articles to the genre each month was a good thing in my view. (This also probably explains why the issues of Dragon I was most fond of ran from 80s to the early 100s – corresponding very closely to the lifespan of the Ares Section).Gamma World was well represented in the Ares Section, frequently presenting articles penned by creator James Ward, which I appreciated, given my obsession with official-dom. One of my favorite articles from Ward was published in issue 88 (August 1984), called "Before the Dark Years." It presents a historical timeline of the Gamma World setting, beginning (as all post-apocalyptic timelines do) in 1945 with the first use of nuclear weapons and ending in 2450, which was the approximate start of the 2nd edition of the game (1st edition began later, in 2471 – why the change, I wonder?).

It's true that the article appealed to me back then because it scratched a completist urge to know it all, an urge I have long since – and happily – abandoned. But back then it was simply awesome to know, for example, that the starship Warden was launched in 2290. Re-reading the article, I still love it, but for rather different reasons. I like it for entries like this one:

2322 – Processed-iced asteroid (guidance circuits damaged by terrorists) strikes Mars; eight-year duststorm and climatic disruption result. All colonies on planet isolated; Federation charter suspended for the duration.Or this one:

2331 – Trans-Plutonian Shipyards assume control of their own programs and generate robotic "life."The reason I love entries like these is that they hit home that Gamma World's apocalypse doesn't happen in the here and now but in a science fictional future. That ought to be obvious, given the presence Mark VII blasters and black ray guns and so forth, but, somehow, it's easy to forget, perhaps because, in the 70s and 80s, worrying about the End of All Things focused on the present, not the future. Indeed, lots of people didn't think there would be a future, thanks to the Damoclean threat of Armageddon.

Gamma World didn't take that approach. Instead, it's set in the future and the weapons that usher in the Dark Years include not just nuclear missiles but also "dimension-warp" devices and other weaponry undreamed of in our age. I think that set Gamma World apart from other post-apocalyptic games, imbuing it with a more "wondrous" quality and also, if I may wax sociological for a moment, making it a little less frightening to kids like me.

The Morrow Project

, to cite one example, postulates that the End would come in 1989 as a consequence of Cold War foolishness and, however absurd its specifics, that was a scenario many people genuinely believed might occur in their lifetimes. But a 24th century terrorist group called the Apocalypse? Using dimension-warp weapons and striking at not just Earth but space colonies as far away as the Oort Cloud? That's clearly fantasy and a lot less terrifying.

Gamma World didn't take that approach. Instead, it's set in the future and the weapons that usher in the Dark Years include not just nuclear missiles but also "dimension-warp" devices and other weaponry undreamed of in our age. I think that set Gamma World apart from other post-apocalyptic games, imbuing it with a more "wondrous" quality and also, if I may wax sociological for a moment, making it a little less frightening to kids like me.

The Morrow Project

, to cite one example, postulates that the End would come in 1989 as a consequence of Cold War foolishness and, however absurd its specifics, that was a scenario many people genuinely believed might occur in their lifetimes. But a 24th century terrorist group called the Apocalypse? Using dimension-warp weapons and striking at not just Earth but space colonies as far away as the Oort Cloud? That's clearly fantasy and a lot less terrifying.As I noted recently, my preferred way to play Gamma World is to treat the post-apocalyptic world as largely a blank slate, one utterly unfamiliar to the characters, who not only grew up generations removed form the Fall, but are played by people for whom even the pre-Fall world is alien. That pre-Fall world included settlements on the Moon, Mars, and elsewhere, is supported by robots, cyborgs, and A.I.s, and is launching extra-solar colonization efforts. That creates a lot of scope for terrific adventures and campaigns; I might even go so far as to say that, as developed in this and other articles, Gamma World provides a canvas every bit as large as that offered by Dungeons & Dragons. Sadly, the game has largely been treated as a joke by its custodians over the years, its full potential never quite realized and that's too bad.

Lessons Learned

With The Shadow over August now complete, I’ve been reflecting on the experience of writing it. This was the first time I’d ever devoted an entire month to a single “theme,” unless you count those old blog challenges that used to make the rounds back in the early days of Grognardia. I took part in at least one of those during what I like to call the First Age of the blog. However, The Shadow over August was different in both purpose and content, which is why it’s left me with so many thoughts.

In fairness, it wasn’t completely unlike a blog challenge in one key respect: it gave me a convenient frame for my writing. One of the hardest parts of maintaining a blog – especially when aiming for daily posts – is figuring out what to write. I’m never short of ideas, but not all of them are ready to be developed and my attention tends to bounce between a dozen threads at once. That usually results in an eclectic mix of posts, which I know some readers enjoy, but it also makes it harder for me to build momentum toward something more substantial.

Having a clear focus last month, namely, Lovecraft and his legacy, helped channel my creative energy in a way I haven’t experienced in years. August turned out to be my most productive month of 2025, surpassing even July. More importantly, I feel the quality of my posts was higher overall, with at least one standing among the best I’ve written since returning to blogging five years ago. In that respect, The Shadow over August was a real gift to me, providing a framework that sharpened both my productivity and my creativity.

That said, that same framework also acted as a kind of restraint. Even though not every post last month was about Lovecraft, most of them were and, when other ideas occurred to me, I often hesitated to post them. On some level, it felt wrong to break the flow of Lovecraftian content with posts on unrelated gaming topics or news about Grognardia Games Direct. The focus was liberating but also limiting in ways I hadn’t expected. The flipside of this is that, now that The Shadow over August is over, I almost feel sheepish about making any more Lovecraft posts, despite the fact that I still have a lot more to say about him, his works, and his influence of roleplaying games.

That's, of course, one of the other unexpected outcomes of last month: I gained a new appreciation of HPL's Dreamlands stories, so much so, in fact, that I'm now devoting myself to the development of an Old School Essentials-derived Dreamlands RPG, Dream-Quest. I certainly didn't intend to be so inspired that my head was suddenly overflowing with ideas for such a game and yet here I am. The Muse is mysterious. Rather than try to puzzle out her motives, I have simply decided to let her guide me where she will. Whether this results in anything substantial or just another half-finished project, who can say?

I think, on balance, the experiment was a successful one, so much so that I've already begun contemplating doing another one in the future, perhaps in January, which is the birth month of both Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith (and J.R.R. Tolkien and Abraham Merritt and Edgar Allan Poe and ...). However, a lot will depend on how my various projects evolve over the course of the coming weeks and months. I feel as if I've been on something of a creative roll lately and I'm honestly struggling a bit to decide which projects deserve my attention.

While there's no danger that I will abandon this blog, is writing a post every day something I can sustain over the long term, especially when there's so much more I want to do (and that, I must be honest, literally repay the time and effort I put into them)? I really don't know, hence my experimentation with different platforms, formats, and content over the last few months. I can't help but feel that I'm in the midst of a long-delayed metamorphosis. Ultimately, I think that'll be a good thing, but the intervening stages might be a little ugly and messy and, for that, I apologize in advance.August 31, 2025

The End(?) of Pulp Fantasy Library

In Grognardia's early days, one of its signature features was Pulp Fantasy Library. If you glance at the “Popular Topics and Series” box down the right-hand column, you’ll see more than 300 entries under that heading. The idea was simple: highlight the works of pulp fantasy literature that shaped not only my own imagination but, more importantly, those that shaped founders of the hobby of roleplaying. Like so much of Grognardia, Pulp Fantasy Library grew out of my conviction that you can’t really grasp the origins of RPGs without engaging the books, authors, and ideas that inspired it.

Of course, the series didn’t stay neatly confined. Over time, I pushed at its boundaries, sometimes gleefully so. I wrote not only about sword-and-sorcery or weird tales but also about science fiction, horror, comics, movies, and the occasional oddball work that defied easy categorization. I often made light of this stretching of definitions, but, in truth, I was doing something larger, namely, charting the imaginative landscape that predated and nourished the hobby. RPGs didn’t spring from nowhere, after all, and Pulp Fantasy Library was my way of mapping the soil they grew in.

The Shadow Over August reminded me of just how much I enjoyed this work. Revisiting four of Lovecraft’s stories made two things clear. First, there’s still a vast reservoir of older literature, much of it influential on RPGs, some of it simply worth reading, about which I've never written. Second, doing these posts properly is no small task. Reading (or rereading), researching context, and writing thoughtfully about them takes a great deal of time and energy, more than I can always justify with so many other projects competing for my attention these days.

Much as it might seem otherwise, Grognardia remains a hobby project and hobbies come with limits. That’s part of why I find myself asking whether Pulp Fantasy Library has already run its course and there's really no need to revive it – or perhaps is it ready for a metamorphosis of some kind? Many of the works I’d still like to tackle don’t sit comfortably within the strict “pulp fantasy” label. Maybe the time has come to evolve the series into something broader, which reflects the full range of the cultural and literary roots from which roleplaying sprang.

I haven’t made up my mind about whether or not I should return to the series and, if so, in what form or frequency. What I do know is this: I remain as fascinated by these seminal works as ever and I believe they still matter deeply to anyone who cares about where our hobby came from. The real question is whether readers share that conviction strongly enough to make it worthwhile for me to continue.

Do you want to see Pulp Fantasy Library return in some form? Is this the kind of writing you value from Grognardia? Let me know. Your responses and, frankly, your encouragement will help me decide not only the fate of Pulp Fantasy Library but also the future direction of the blog itself.August 30, 2025

One of Us

As we draw

The Shadow over August

to a close, I'd like to end this series with a moment of reflection. Celebrating H.P. Lovecraft is, for many, a complicated endeavor. It has become fashionable in recent years to criticize him, to magnify his personal flaws while downplaying the extraordinary influence he has had on the worlds of fiction, pop culture (including roleplaying games), and imagination itself. Yet, for all his faults, both human and literary, I have come to see Lovecraft as something more than a historical figure or a subject of controversy. I see him as a kindred spirit.

As we draw

The Shadow over August

to a close, I'd like to end this series with a moment of reflection. Celebrating H.P. Lovecraft is, for many, a complicated endeavor. It has become fashionable in recent years to criticize him, to magnify his personal flaws while downplaying the extraordinary influence he has had on the worlds of fiction, pop culture (including roleplaying games), and imagination itself. Yet, for all his faults, both human and literary, I have come to see Lovecraft as something more than a historical figure or a subject of controversy. I see him as a kindred spirit.Lovecraft was, in so many ways, like many of us who have found solace in books, in quiet contemplation, and in worlds of our own making. He was shy, intensely bookish, and at odds with the modern world and its demands, yet he also cultivated wide friendships and a network of mutual support that enriched both his life and the lives of those around him. He endured profound loss and personal difficulty throughout his life, from the death of his father while a child to the even greater loss of his beloved grandfather to a mother whose protectiveness sometimes smothered him Despite that, he carved out a life of meaning through his imagination, his letters, and his multitude of friends.

No one is without flaws and Lovecraft’s were many. But the measure of a man is not in perfection. It is in persistence, in the courage to create, to connect, and to leave something lasting by the time we depart this sublunary existence. In this, Lovecraft succeeded in ways few could. For me, he is a fellow nerd, a fellow writer, and a fellow introvert who managed to create not only stories but, just as importantly, friendships, a community, and a legacy that continues to shape the way we imagine and tell tales decades after his death.

I hope that in following The Shadow over August, readers might come to understand not just Lovecraft’s works, but the man behind them – flawed, human, brilliant, and strangely relatable. Perhaps, in some small way, I hope readers might also recognize in his life the quiet courage it takes to pursue one’s own path, to cultivate one's own circle, and to leave one's mark on the world.

Lovecraft, with all his contradictions, reminds me that being a nerd, being a dreamer, and being devoted to one’s craft are virtues worth celebrating. That, after all, is the real reason why I have spent this month writing in his honor. I hope you have enjoyed it.Interview: Jeff Talanian

1. How did you first discover the works of H.P. Lovecraft and what was it about his writing that captivated you?

1. How did you first discover the works of H.P. Lovecraft and what was it about his writing that captivated you?Greetings, James, and thank you for the opportunity to chat about one of my favorite authors, H.P. Lovecraft. So, when I was a young teenager in the early- to mid-1980s, I was playing in a local AD&D group that was run by a childhood friend by the name of Andrew. One week, my friend Bob, whom I am still friends with to this day, wanted to run something different for the group as a one-shot. It was Call of Cthulhu, by Chaosium. I played a scientist armed with a pistol, and my guy either died or went mad – I don't recall the specifics. But I loved the content, and it led me to looking up the story "The Call of Cthulhu," by Mr. Lovecraft, and it's since been a lifelong fascination. So, I discovered HPL through gaming. I think it was about 1983 or 1984.

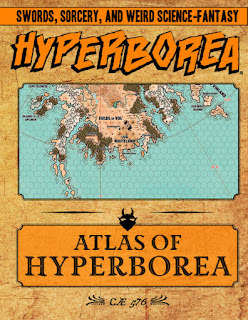

2. Lovecraft’s influence on Hyperborea is unmistakable. What elements of his cosmic horror do you think best lend themselves to tabletop roleplaying?

The crushing sense of futility in which mankind must come to terms that he is an insignificant ant in comparison with the Great Old Ones; that no matter how much he achieves, whatever lofty heights he attains, there is something larger out there that views man with indifference, if even at all. It is a different mindset than some previous presentations in which player characters can actually achieve a god-like status or even become immortals with all the benefits derived therefrom. In a true cosmic horror campaign, for no matter how much power and glory you achieve, you are still no more than the aforementioned ant in the grand scheme of things.

3. Lovecraft is often associated with "modern" horror, but Hyperborea is firmly sword-and-sorcery. How do you blend the alien terrors of the Mythos with the more grounded violence and heroism of pulp fantasy?

I drew a lot of inspiration from HPL's brothers-in-arms, as it were – Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, and no small amount of inspiration from other authors such as Abraham Merritt and Fritz Leiber. As Howard and Lovecraft became closer friends, as evidenced by the letters they exchanged, we started to see the influences of cosmic horror played out in Howard's fiction, which was a subtle shift away from some of his earlier themes of more heroic, action-oriented yarns. This also applies to Smith's work, which borrows from Lovecraft's work, but in a lot of cases, HPL was borrowing from CAS (see Tsathoggua). So, even though HPL was writing a lot of his works from a modern (for his time) perspective, and other authors have since done the same, I think it should be recognized that authors such as REH and CAS were taking these same concepts and themes and applying them to other worlds and other times of a more fantastic bent.

4. What’s your favorite Lovecraft story, and why? Has it ever directly influenced an adventure or mechanic in Hyperborea?

"The Shadow Out of Time" is not only a personal favorite, but also one that I have derived a great amount of inspiration from for the entire Hyperborea adventure game itself. In 2008, in the aftermath of Gary Gygax's passing, whom I'd been working for three years as a writer, I found myself back to square one. I decided to make my own game that I would enjoy playing with my beer-drinking buddies, and if other gamers liked it – great! If they didn't, then to hell with them! I wanted my game to be built out from and inspired by earlier systems by Gygax and Arneson, and I wanted its setting to have a Bran Mak Morn, Conan, and Kull feel to it, but with a heavy dose of the weird fiction produced by Howard's friends, H.P.L. and C.A.S. At the time, I was rereading all of Lovecraft's works, and when I read "The Shadow Out of Time," I had an epiphany. It was inspired by the following passages:

"The Shadow Out of Time" is not only a personal favorite, but also one that I have derived a great amount of inspiration from for the entire Hyperborea adventure game itself. In 2008, in the aftermath of Gary Gygax's passing, whom I'd been working for three years as a writer, I found myself back to square one. I decided to make my own game that I would enjoy playing with my beer-drinking buddies, and if other gamers liked it – great! If they didn't, then to hell with them! I wanted my game to be built out from and inspired by earlier systems by Gygax and Arneson, and I wanted its setting to have a Bran Mak Morn, Conan, and Kull feel to it, but with a heavy dose of the weird fiction produced by Howard's friends, H.P.L. and C.A.S. At the time, I was rereading all of Lovecraft's works, and when I read "The Shadow Out of Time," I had an epiphany. It was inspired by the following passages:

I learned—even before my waking self had studied the parallel cases or the old myths from which the dreams doubtless sprang—that the entities around me were of the world’s greatest race, which had conquered time and had sent exploring minds into every age. I knew, too, that I had been snatched from my age while another used my body in that age, and that a few of the other strange forms housed similarly captured minds. I seemed to talk, in some odd language of claw-clickings, with exiled intellects from every corner of the solar system.

There was a mind from the planet we know as Venus, which would live incalculable epochs to come, and one from an outer moon of Jupiter six million years in the past. Of earthly minds there were some from the winged, star-headed, half-vegetable race of palaeogean Antarctica; one from the reptile people of fabled Valusia; three from the furry pre-human Hyperborean worshippers of Tsathoggua; one from the wholly abominable Tcho-Tchos; two from the arachnid denizens of earth’s last age; five from the hardy coleopterous species immediately following mankind, to which the Great Race was some day to transfer its keenest minds en masse in the face of horrible peril; and several from different branches of humanity.

Here was a story showing me exactly what I needed to do with my setting and how I could pull it all together – whether you are talking about Kull's Valusia, the Elder Things of Antarctica, or Tsathoggua worshipers of Hyperborea – it was all there! I then began to conceive of an idea of an adventure game setting in which all these elements could be pulled together, and more!

5. You’ve cited not just Lovecraft but also Howard, Smith, and Merritt as inspirations. What do you think the shared thread is among these authors and how does Hyperborea pay homage to that tradition?

I think that each and all they were incredibly imaginative writers who dared to write for a genre that was largely shunned, and they were excelling at it. I believe they wrote "up" to their readers, and never catered to a lowest common denominator to increase sale. Their themes were complex, thoughtful, and induced a range of emotions from curiosity to dread to fear. Sure, I have tried to pay homage to this in my works and the works I'm overseeing, and I hope that my stuff has honored the great pulp tradition (at least in gaming form).

6. What does pulp fantasy offer that contemporary fantasy often neglects or downplays?

Contemporary fantasy has largely been stuck in Tolkien's back yard for many years. It's not a bad backyard to be trapped in, because the good professor was one of the greatest practitioners of literature to ever do it, and there have been some wonderful homages to his works. Pulp fantasy is different. It often features a single viewpoint protagonist, it's usually not about saving the world, and it has a more immediate, realistic feel to it, even if the things experienced are beyond the mundane. They often feature an unexpected twist at the end that results in the death of the protagonist or worse, so you are almost always at the edge of your seat when reading these fantastic tales.

7. You've continued to refine and expand Hyperborea across its editions. Has your approach to incorporating Lovecraftian elements evolved over time?

I think conceptualizing a world setting in which Lovecraftian elements are real and present is something that I am always trying to see improved or evolved, as you put it. For example, a ranger in Hyperborea is not a specialist versus humanoids and giants; rather, he is a specialist against otherworldly creatures whose objectives do not accord with the welfare of mankind. So, rangers in Hyperborea hunt Mi-Go, the Great Race, Night Gaunts, and so forth. The content we produce touches on this, in a world that has seen mankind nearly wiped out by a star-borne contagion and now clings to a meager existence in which these many horrors abound.

8. Do you think there's such a thing as too much Mythos in an RPG? Can it become over-familiar or even cliché?

I think if it is done well, with purpose and a vision that is worked hard for, it can never be too much. Imagine, if you will, how many people in the last two millennia have studied the classics, reading and rereading The Odyssey and The Iliad. So, I don't think the Mythos will ever get old, but as readers become more savvy, they will discern between quality pastiche and silly pastiche.

I think if it is done well, with purpose and a vision that is worked hard for, it can never be too much. Imagine, if you will, how many people in the last two millennia have studied the classics, reading and rereading The Odyssey and The Iliad. So, I don't think the Mythos will ever get old, but as readers become more savvy, they will discern between quality pastiche and silly pastiche.9. As a game designer and worldbuilder, what lessons have you learned from Lovecraft’s approach to mythmaking and the unknown?

I learned that we, as designers and world builders, should not feel bound to the religions and myths of the ancients when conceptualizing and exploring antemundane concepts. Anyone can create a world or a setting that draws inspiration from known works but also has the audaciousness to explore and develop strange new worlds and realities. You just have to have the stubbornness to do it, dismissing naysayers and detractors. Do what thou wilt, my friends.

Thank you for having me, James. Cheers!August 29, 2025

Hyperborea's Lovecraftian Adventures

As The Shadow over August draws to a close, I keep catching myself thinking about the posts I never got around to writing. That seems to be the curse of writers everywhere. It’s all too easy to dwell on the missed opportunities instead of celebrating the pieces that did make it to the page. One post in particular keeps nagging at me: an exploration of RPG adventures that wear their Lovecraftian influence on their sleeve, whether through mood, themes, or outright horrors. Since time is short and a full treatment is no longer possible, I’ll settle for the next best thing: highlighting three terrific Hyperborea modules that practically drip with Lovecraftian atmosphere, strange terrors, and otherworldly monsters.

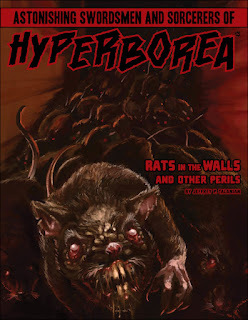

Rats in the Walls: Sharing its title with one of Lovecraft’s most famous tales, this collection offers three short adventures for levels 1–2. Each works perfectly as the start of a new Hyperborea campaign, though the standout is the namesake scenario: helping a desperate Khromarium tavernkeeper rid his alehouse of an unsettling infestation of otherworldly rats. The set also includes "The Lamia’s Heart," a tense caper centered on the attempted theft of a legendary gem from a wealthy merchant’s mansion, and "The Brazen Bull," a foray into a crumbling temple of Thaumagorga, Daemon Lord, where a sinister new power is beginning to stir.

Rats in the Walls: Sharing its title with one of Lovecraft’s most famous tales, this collection offers three short adventures for levels 1–2. Each works perfectly as the start of a new Hyperborea campaign, though the standout is the namesake scenario: helping a desperate Khromarium tavernkeeper rid his alehouse of an unsettling infestation of otherworldly rats. The set also includes "The Lamia’s Heart," a tense caper centered on the attempted theft of a legendary gem from a wealthy merchant’s mansion, and "The Brazen Bull," a foray into a crumbling temple of Thaumagorga, Daemon Lord, where a sinister new power is beginning to stir.

The Mystery at Port Greely: This level 4–6 adventure doesn’t just echo Lovecraft’s

The Shadow over Innsmouth

: it embraces the same eerie vibe while spinning it into its own dark tale. The player characters arrive in the coastal town of Port Greely to investigate the unexplained disappearance of envoys from Khromarium’s Fishmongers’ Guild. Needless to say, what's happening here isn't very pleasant – a fact made all the more apparent when they meet the locals, whose fish-like appearance points to the horrible truth. The more the characters dig, the clearer it becomes that something profoundly inhuman is lurking in Port Greely.

The Mystery at Port Greely: This level 4–6 adventure doesn’t just echo Lovecraft’s

The Shadow over Innsmouth

: it embraces the same eerie vibe while spinning it into its own dark tale. The player characters arrive in the coastal town of Port Greely to investigate the unexplained disappearance of envoys from Khromarium’s Fishmongers’ Guild. Needless to say, what's happening here isn't very pleasant – a fact made all the more apparent when they meet the locals, whose fish-like appearance points to the horrible truth. The more the characters dig, the clearer it becomes that something profoundly inhuman is lurking in Port Greely. The Sea-Wolf's Daughter: At 60 pages, this level 7–9 adventure is the biggest of the three and the most unabashedly “weird science-fantasy” of the lot. On the surface, it’s about the abduction of a Viking jarl’s daughter by a notorious pirate. But beneath that pulpy premise lies a heady mix of Lovecraftian horror and science-fantasy: nightgaunts, elder things, alien technologies, and the looming weight of cosmic dread. Imagine Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, and Jack Kirby locked in a fever-dream collaboration, and you’ll have something of the adventure's flavor. It’s a great showcase of what makes Hyperborea such a distinctive game and one that I have long admired.

The Sea-Wolf's Daughter: At 60 pages, this level 7–9 adventure is the biggest of the three and the most unabashedly “weird science-fantasy” of the lot. On the surface, it’s about the abduction of a Viking jarl’s daughter by a notorious pirate. But beneath that pulpy premise lies a heady mix of Lovecraftian horror and science-fantasy: nightgaunts, elder things, alien technologies, and the looming weight of cosmic dread. Imagine Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, and Jack Kirby locked in a fever-dream collaboration, and you’ll have something of the adventure's flavor. It’s a great showcase of what makes Hyperborea such a distinctive game and one that I have long admired.Of course, what unites all three of these fine modules is their author, Jeff Talanian, the creator of Hyperborea and a tireless promoter of pulp fantasy. I recently put a few questions to Jeff about Hyperborea and its ties to HPL and he kindly offered some responses, all of which will appear in an interview to be published later today. I hope you'll enjoy his answers as much as I've enjoyed Jeff's adventures.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers