James Maliszewski's Blog, page 9

August 9, 2025

Special Delivery

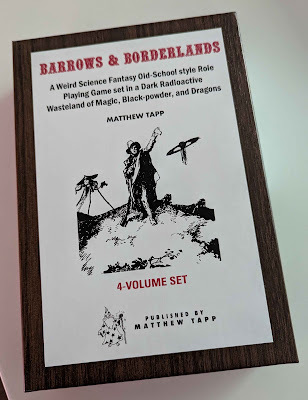

Last month, I mentioned Barrows & Borderlands, a new old school RPG created by Matthew Tapp. A couple of days ago, my copy of the 4-volume boxed set arrived in the mail and I was so impressed with it that I wanted to show it off. Here's the front of the OD&D-inspired woodgrain boxed set.

Here's the side of the box.

Here's the side of the box.

This is a shot of the open box, with all four of its integral volumes: Men & Mutants, Psychics & Sorcerers, Horrors & Treasure, and The Underworlds & Borderlands Adventures.

This is a shot of the open box, with all four of its integral volumes: Men & Mutants, Psychics & Sorcerers, Horrors & Treasure, and The Underworlds & Borderlands Adventures.  I have not yet had a chance to delve deeply into the books yet, but what I have seen so far has really impressed me, all the more so, because, as I mentioned previously, Matthew and the players in his campaign are all much younger than the usual cohort for old school roleplaying games. It's really heartening to see the spirit of the old days is still very much alive, even among people less than half my age.

I have not yet had a chance to delve deeply into the books yet, but what I have seen so far has really impressed me, all the more so, because, as I mentioned previously, Matthew and the players in his campaign are all much younger than the usual cohort for old school roleplaying games. It's really heartening to see the spirit of the old days is still very much alive, even among people less than half my age. I'll have more to say about B&B in the days to come.

August 8, 2025

Interview: Sean McCoy

My next interview for the Shadow over August is Sean McCoy, creator of the roleplaying game,

Mothership

. Mothership is a sci-fi horror game in the tradition of movies like Alien, The Thing, and Event Horizon, all of which clearly show a Lovecraftian influence. Consequently, I reached out to Sean and he kindly agreed to answer my questions not just about Lovecraft but also about Mothership and what it has to offer fans of science fiction and horror RPGs.

My next interview for the Shadow over August is Sean McCoy, creator of the roleplaying game,

Mothership

. Mothership is a sci-fi horror game in the tradition of movies like Alien, The Thing, and Event Horizon, all of which clearly show a Lovecraftian influence. Consequently, I reached out to Sean and he kindly agreed to answer my questions not just about Lovecraft but also about Mothership and what it has to offer fans of science fiction and horror RPGs.1. To what extent was H.P. Lovecraft an influence on Mothership? Were there specific stories or concepts you feel that directly or indirectly shaped the game’s tone or mechanics?

One of my best friends got into Lovecraft when we were in high school. It went completely over my head. But through him I got into Call of Cthulhu. It’s still one of the scariest RPG memories I’ve ever had. That and the idea that your characters could be on this downward spiral rather than becoming more powerful really appealed to me.

Stories that Lovecraft influenced have had a larger impact on me: Berserk, The Mist, The King in Yellow, Thomas Ligotti, Clark Ashton Smith, The Thing, Annihilation, Amnesia: Dark Descent, Hellboy, Providence, Half-Life, Junji Ito, Event Horizon. At the Mountains of Madness — particularly the manga adaptation by Gou Tanabe — always looms large in my mind.

2. Lovecraft famously emphasized fear of the unknown and mankind’s insignificance in the cosmos. Did you translate those themes into the actual play experience of Mothership and, if so, how?

That’s a big part of what we’re trying to do. We didn’t want Mothership to feel like a fun romp around the galaxy with talking aliens or knowable alien civilizations like in Star Wars or Mass Effect. We wanted space to feel like a lonely desert highway to nowhere. A lot of this comes down to how we choose what modules we write.

That’s a big part of what we’re trying to do. We didn’t want Mothership to feel like a fun romp around the galaxy with talking aliens or knowable alien civilizations like in Star Wars or Mass Effect. We wanted space to feel like a lonely desert highway to nowhere. A lot of this comes down to how we choose what modules we write. 3. The Stress and Panic mechanics in Mothership are central to the game. Are these meant to evoke the classic Lovecraftian “descent into madness” or did you have something different in mind?

No, by the time Mothership arrived on the scene, Call of Cthulhu had already staked its claim to that territory. And the whole like “person go cuckoo” vibe isn’t our thing. Nearly everyone now openly struggles with their mental health and that’s a positive thing. More people seek help and get treatment. We wanted to find those breaking points where someone snaps because of the immense pressure they’re under. In 1e we moved away from more clinical language when we described panic for exactly this reason.

4. In Lovecraft's own stories, the protagonists rarely “win." They survive, if they’re lucky. How do you balance that kind of grim narrative tone with the needs of an enjoyable RPG session?

We call it "Survive, Solve, Save: Pick Two." Survive the ordeal. Solve the mystery. Save the day. I think some of it is about your play culture. DCC has players reveling in death due to their awesome funnels and their general 70s airbrushed van aesthetic. Over time, we’re building up a library of more mundane adventures. Ones that are stressful but not necessarily interacting with cosmic horror every week. Additionally, we’re trying to encourage wardens to take a longer view of campaigns. Putting months or years between adventures rather than the typical adventuring day from D&D.

5. Do you see the derelict ship or space station in a Mothership scenario as an extension of the haunted house or ruined temple in Lovecraft's fiction?

Yeah, I’m obsessed with abandoned and forgotten places but my touchstone for that is largely D&D. Ruined architecture, cold case mysteries, “what happened here?” These questions are always at the forefront of my mind. With At the Mountains of Madness, this forgotten ancient civilization is fascinating to me. Particularly if it transforms your idea of your place in the universe. This is a theme we’re going to explore soon in an upcoming module (tentatively titled Word of God).

Yeah, I’m obsessed with abandoned and forgotten places but my touchstone for that is largely D&D. Ruined architecture, cold case mysteries, “what happened here?” These questions are always at the forefront of my mind. With At the Mountains of Madness, this forgotten ancient civilization is fascinating to me. Particularly if it transforms your idea of your place in the universe. This is a theme we’re going to explore soon in an upcoming module (tentatively titled Word of God). 6. How do you view Mothership’s place in the broader tradition of “weird science fiction”? Are there other weird authors beyond Lovecraft you see as inspirations?

The big one for me is Brian Evenson. One of my absolutely favorite authors. His story. "The Dust," in the collection A Collapse of Horses is the closest thing to a direct inspiration for Mothership outside of the Alien franchise. Evenson is a superb author, just so much fun to read. We’re now commissioning our own short fiction and comics for our Megadamage magazine from authors like Patrick Loveland, Anthony Herrera, and Nick Grant, so we hope to be contributing more to weird fiction tradition soon.

7. Lovecraft’s work often implies a kind of cosmic fatalism – that knowledge brings ruin, that humanity is a passing accident. Does Mothership share that worldview or do you see room for resistance or even hope?

In Mothership, player characters rarely defeat the big evil. But often they live to fight another day or they step the tide another day. They keep back the darkness another day. And even if they perish, someone else will pick up the distress signal or the message or the captains log and continue the work. I don’t view it as hopeless and nihilistic. I look at it like the great work of transforming your life or others is a work for many people across time and space working together whether they know it or not. Which to me is profoundly hopeful.

8. What are the unique challenges of presenting horror in an RPG context, where players can make choices, derail scenarios, and joke around at the table? Can you keep the tone intact or is that not even a concern?

To us it’s not much of a concern. Whether a player gets scared at the table is so far out of our control that we don’t even think about it. People will joke around and order pizza and look up rules and none of that is conducive to getting scared. That being said, “where is the horror?” is a common refrain among our development team. We want to allow for the possibility that an encounter can be scary, if the group is in the mood, but we make it clear in our Warden’s Operations Manual, that this isn’t some bar to clear in order to have a successful game. Fun is our only bar.

To us it’s not much of a concern. Whether a player gets scared at the table is so far out of our control that we don’t even think about it. People will joke around and order pizza and look up rules and none of that is conducive to getting scared. That being said, “where is the horror?” is a common refrain among our development team. We want to allow for the possibility that an encounter can be scary, if the group is in the mood, but we make it clear in our Warden’s Operations Manual, that this isn’t some bar to clear in order to have a successful game. Fun is our only bar. 9. Are there any lessons you’ve taken from Lovecraft, positive or negative, about how to portray horror in an interactive medium?

So, Lovecraft’s horror is deeply personal, reflecting his worst qualities and odious worldview. His racism and xenophobia, eugenics, fear of the city, he’s just the worst. It’s a reminder that when we’re talking about our fears we’re talking about a really core part of who we are. So, for me as a writer that often means thinking about the things I am deeply afraid of and shining a light on them.Story Isn't the Enemy

Among the many shibboleths of the Old School Renaissance, few are as enduring as the rejection of "story," "plot," and "narrative" in roleplaying games. These terms are often treated like contaminants, indicators that something has gone awry in a campaign or adventure. Speak of "story" without the usual ritual denunciations and you're liable to be accused of abandoning the principles of old school play.

Among the many shibboleths of the Old School Renaissance, few are as enduring as the rejection of "story," "plot," and "narrative" in roleplaying games. These terms are often treated like contaminants, indicators that something has gone awry in a campaign or adventure. Speak of "story" without the usual ritual denunciations and you're liable to be accused of abandoning the principles of old school play.I understand where this aversion comes from. Since the earliest days of this blog, I've often shared it. At the same time, I don't believe stories have no place in roleplaying games. However, like many others, my earliest experience as a roleplayer were from a time when attempts to inject "story," – by which I mean a deliberate, authorial structure of rising and falling action, dramatic turning points, and satisfying resolutions – were usually ham-fisted at best and outright railroads at worst.

There’s a reason why one of Grognardia’s most widely read (and most frequently argued about) posts is “How Dragonlance Ruined Everything.” The post touched a nerve because it spoke to something many of us experienced firsthand: modules and campaigns that confused narrative structure with narrative control. These were adventures where the outcomes were preordained, its dramatic beats carefully plotted, and the players expected to play along rather than play through. The referee, in such cases, became less an impartial adjudicator and more a frustrated novelist trying to drag the player characters through a plot that offered very little in the way of choice. Unsurprisingly, this left a bad taste in the mouths of those who cherished the open-ended freedom of the early days.

But here’s the thing: an emergent story is still story.

Take my House of Worms campaign for Empire of the Petal Throne. More than a decade of weekly play has produced a very detailed chronicle of events, consisting of actions taken, choices made, consequences endured, victories won, and, occasionally, defeats suffered. None of this was plotted out in advance. Most of it arose organically, through the interaction of player decisions, random tables, misread intentions, and lucky – or bad – rolls. Yet, looking back, I can trace arcs and patterns. I can recount the rise and fall of rivalries and the strange twists of fate that brought certain aspects of the campaign to greater prominence while others dropped away. I can talk about betrayals and reconciliations, discoveries and reversals. That’s a story. It may not be a tidy one. It may not resolve neatly – but it's a story nonetheless.

Too often, I think certain strands of OSR thought fails to acknowledge this and I don't exclude myself from this criticism. In rejecting plotted stories, we too quickly rejected the very idea of story itself. However, stories don’t have to be plotted. They don’t have to follow the Hero’s Journey. They don’t even need to have a central protagonist. They can simply emerge from play, from the piling up of decisions and consequences, the unpredictable results of dice rolls, and the slow evolution of characters over time. This is, in my view, one of the greatest strengths of the hobby.

Likewise, many classic modules – yes, even old school ones – contain what we might call a plot, even if it's implicit or only lightly sketched. A fortress inhabited by giants who've been raiding civilized lands is not just a list of rooms and monsters. It's a framework for conflict, danger, and mystery. It implies certain questions and challenges: Who are these giants? What do they want? Why are they raiding the lands of Men? These questions don’t force a narrative, but they do provide the raw material out of which one might grow. A good adventure isn’t inert; it suggests motion and consequence, even if it doesn’t prescribe them.

That’s where I think the OSR’s kneejerk hostility to “story” often goes astray. It’s an understandable overreaction, but an overreaction nonetheless. It’s shaped by the bad experiences of railroads, boxed text, and scripted scenes. However, in pushing back against those things, we risk throwing out something valuable. If we mistake any form of narrative structure for narrative imposition, we blind ourselves to one of the most powerful and rewarding aspects of roleplaying: the ability to discover a story in play, rather than impose one from above.

The truth is that most open-ended, player-driven campaigns do produce stories. Often, they’re some of the most compelling stories in gaming, precisely because no one saw them coming. They're not crafted to deliver a message or to hit emotional beats on cue. They arise naturally, shaped by the decisions of players and the impartial logic of dice. We should be able to recognize that without fear. Story isn’t the enemy; control is. Let the dice decide, let the players choose and the story will take care of itself.August 7, 2025

Suspense

August 6, 2025

The Dream-Quest of the Old School Renaissance

Earlier this week, in the first entry of the (temporarily?) revived Pulp Fantasy Library series, I wrote about H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Silver Key.” Though that short story isn't at all what one might regard as a horror tale, there's nevertheless a moment that haunts me. The protagonist, Randolph Carter, now middle-aged, has discovered that he can no longer dream. He can no longer reach the realms that once filled his youthful sleep with wonder. The real world, with its routines, explanations, and disappointments, has closed in around him. What’s terrifying here isn’t what lies beyond the stars, but what no longer lies within: imagination itself.

Earlier this week, in the first entry of the (temporarily?) revived Pulp Fantasy Library series, I wrote about H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Silver Key.” Though that short story isn't at all what one might regard as a horror tale, there's nevertheless a moment that haunts me. The protagonist, Randolph Carter, now middle-aged, has discovered that he can no longer dream. He can no longer reach the realms that once filled his youthful sleep with wonder. The real world, with its routines, explanations, and disappointments, has closed in around him. What’s terrifying here isn’t what lies beyond the stars, but what no longer lies within: imagination itself.For Lovecraft, this was personal. As I explained in my earlier post, “The Silver Key” is an introspective tale of memory, longing, and the slow death of the inner life. The titular key is not just a magical object, but a symbol of return to dreams, to possibility, to the boundless interiority of childhood. Carter finds it in the attic of his boyhood home, tucked away like some forgotten relic. Using it, he travels not only in space but in time, becoming his ten-year-old self again and vanishing into the Dreamlands. "The Silver Key" is, therefore, a story of reclaiming something lost and, Lovecraft suggests, essential. That’s what makes it resonate with me now in a way it didn’t when I first read it as a younger man. Reading it now, as old age creeps up on me with soft and silent feet, I see that the tale speaks to a hunger that fantasy can sometimes feed – a hunger not simply for escape, but for restoration.

Lovecraft wasn’t the only writer of his era to feel this way. Robert E. Howard, his friend and correspondent, also saw the modern world as a spiritual prison. In a letter to Lovecraft, he lamented “this machine age” and its failure to nourish the soul. He believed that many young people yearned for freedom because the world offered so little of it. That yearning animated nearly all of his fiction. Conan the Cimmerian is, if nothing else, free: untamed, unruled, and untouched by the slow death of civilization.

This yearning for freedom crops up in all kinds of unexpected places. You see it in the eyes of motorcyclists when they talk about the road. You taste it in absurdly spicy food meant not to please the palate but to make one feel something. You glimpse it in the half-forgotten dream of space travel or in the stubborn refusal of children to abandon wonder for pragmatism. You also feel it keenly and powerfully in tabletop roleplaying games.

For many of us, RPGs have been a kind of silver key. They’ve opened doors not just to fictional worlds, but to parts of ourselves we feared we’d lost. They’ve let us imagine lives not defined by careers, schedules, or the slow grind of adult compromise. The best roleplaying games recapture something of childhood’s wild creativity, when anything was possible and the laws of reality were made to be bent or broken – when the world could be made anew with a pencil, some dice, and shared imagination.

This connection between fantasy, freedom, and dreams isn’t just thematic but structural. The earliest roleplaying games were dreamlike in their very design. Their dungeons weren’t architectural blueprints; they were symbolic landscapes, more like the underworlds of myth than the ruins of history. Secret doors, teleporting rooms, talking statues, and pools of acid weren’t practical features. They were emblems of mystery, transformation, and risk. They didn’t simulate the world; they enchanted it.

I don’t think this weirdness was an accident. It was a kind of cartography, mapping inner spaces and personal mythologies. Playing D&D in my youth didn’t just feel like being part of a game. It felt like connecting to a hidden tradition, something esoteric and half-occult. It wasn't a gnosis passed from master to pupil but rather photocopies shared in schoolyards and cluttered hobby shops. It was chaotic, yes, but in that chaos lay the promise: you can go anywhere and do anything.

Even if we didn’t fully understand it at the time, I think that’s what many of us in the early days of the Old School Renaissance were trying to reclaim. We wanted not merely older rules, but older visions. We remembered when RPGs weren’t yet respectable. We remembered when they still felt like artifacts from another world, scrawled by strange hands. We remembered when they allowed us to believe, even if for just a few hours, that we could step outside the cage of the everyday, before the world dictated to us what was real and what was merely fantasy.

I do not believe that fantasy, properly understood, is an escape from reality. No, it is an escape to something deeper. It is a return, a recovery, a dream re-entered with eyes open and soul intact. In that sense, every gaming table is an attic and every set of dice a silver key. Whether we’re mapping dungeons, slaying dragons, or simply pretending to be someone else for a while, we are all, in our own way, Randolph Carter, standing once again before the cave in the woods, ready to step through.Notes from the Margins

Notes from the Margins by James Maliszewski

Sample Introductions from Volume 1 of the Grognardia Anthology

Read on SubstackAugust 5, 2025

Retrospective: Alone Against the Wendigo

I've mentioned before that I'm really quite fascinated by the concept of solo roleplaying games and solitaire adventures. I don't have a lot of experience with either of them, aside from my teenage forays into the Fighting Fantasy and related series. From what I understand, they've made a big comeback since the late unpleasantness, so much so, in fact, that quite a few RPGs now include explicit rules for playing the game alone.

Consequently, I missed out entirely on Chaosium's forays into this genre back in the early to mid-1980s, starting with SoloQuest for RuneQuest in 1982. A few years later, the company decided to expand the experiment to include Call of Cthulhu. Given that most Lovecraft stories typically involve a single protagonist, this makes the concept of a solitaire adventure very well suited to its source material, at least in principle.Published in 1985, Alone Against the Wendigo is the first of two solitaire adventures for Call of Cthulhu. Written by Glen Rahman, perhaps best known for the fantasy boardgame, Divine Right, which he co-designed with his brother, Kenneth, the scenario puts the player takes in the role of Dr L. C. Nadelmann. Nadelmann's initials can stand for either Lawrence Christian or Laura Christine, depending on whether the player wishes to play a man or a woman. Dr Nadelmann is a Miskatonic University anthropologist leading a six-person expedition into the Canadian wilderness to investigate tales concerning a monstrous being, the Wendigo. The adventure begins with the assembling of the expedition and the journey northward into the wilds of Northern Ontario, a place of vast snow-covered forests, ancient legends, and unsettling silence. As the days progress, the expedition begins to unravel. Strange noises are heard in the night. Members disappear. The weather turns deadly. In the growing cold and fear, the line between reality and madness begins to blur. Ultimately, Nadelmann must survive not only the physical dangers of the wilderness but also unravel the truth about the Wendigo, an entity tied to cannibalism, madness, and the insatiable hunger of the void.

Like all solitaire adventures, Alone Against the Wendigo sought to provide an experience of playing a RPG, in this case Call of Cthulhu, to players who didn’t have regular gaming groups. How well it succeeded in this is difficult to say objectively. My own experience with solo adventures is that they're really their own thing, distinct both from traditional adventures and from literature, even though their format draws from both. In the case of this particular scenario, which I played through in preparation for this post, I would say that it does an adequate job of conveying a mix of isolation, existential dread, and Mythos-inflected horror. Its remote, frozen wilderness setting does a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of tone, creating a believable and menacing backdrop that mirrors the psychological disintegration of the player.

Like every solitaire adventure with which I am familiar, Alone Against the Wendigo consists of a series of numbered paragraphs that the player navigates in response to choice and the results of dice rolls. Some of the latter are skill rolls (e.g. "Try a Psychology roll. If you succeed, go to –27–; if you fail, go to –29–."), but some are simply random (e.g. "Roll a die; even go to –4–; odd, go to –5–."). This gives the scenario a decent amount of replayability, with branching narratives, multiple choices, outcomes, and side paths. Different decisions, like what gear to bring, how to interact with team members, where to explore, not to mention the aforementioned dice rolls, can thus radically alter the experience. In that respect, I think Alone Against the Wendigo is pretty good.

The adventure's integration of Call of Cthulhu mechanics, like skill and Sanity rolls are handled with a fair degree of elegance. Playing through the scenario still feels like you're playing Call of Cthulhu rather than some inferior imitation of it. That's an impressive feat in itself and I appreciate the care with which the rules were employed here. To be fair, Call of Cthulhu is a pretty mechanically simple game, especially when compared to, say, RuneQuest, but, even so, I think Rahman did a solid job here in translating its gameplay to a solo environment.

Aside from the inevitable limitations of the solitaire format – no game book, no matter how lengthy, could provide for every possibility available in face-to-face play – the main problems with Alone Against the Wendigo, in my opinion, are its underdeveloped NPCs. While all of the expedition members accompanying Dr Nadelmann have distinct roles, few are given much personality or depth, certainly not enough to make their loss (or survival) truly arresting. Again, that's perhaps an inevitable limitation of its format, but, for me at least, I felt it much more keenly than the limited array of choices in many circumstances.

That said, I like Alone Against the Wendigo for its ambition, if nothing else. As the first solo Call of Cthulhu scenario, it deserves credit not only for innovation but for capturing some of the spirit of Lovecraftian horror in a new and accessible format. Despite falling short of its mark in many ways, it demonstrated that horror roleplaying could be a solitary, introspective experience rather than being a group exercise in monster hunting. In that respect, I think it's much truer to its source material than many Call of Cthulhu adventures, even well-loved ones, are. Viewed from that perspective, I can't judge it too harshly.Among the Weirdos

Something I find myself reflecting on more and more as I grow older is just how odd so many of the people I gamed with in my youth were. I mean that in the best possible sense. Back in the late '70s and early '80s, there weren't as many organized outlets for people with niche interests as there are nowadays. If you were into, say, The Lord of the Rings or Star Trek – or if you liked history or mythology or miniature soldiers or even if you read books no one else in your school had heard of, there just weren’t many places you could go to find like-minded souls.

Because of that, my early memories of entering the hobby are filled with eccentrics and enthusiasts, each one weird in his own particular way. I remember, for example, a guy who constantly insisted that "there was no such thing as a 'broadsword' during the Middle Ages." I already told you about Bob. And then there was me, who spent his spare time obsessing over ancient alphabets and cobbling together imaginary languages for the fun of it. Somehow, we all got along – or at least, we all put up with each other long enough to play D&D or Traveller or whatever.

It’s hard to overstate how formative that was for me. For example, I was introduced to Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard by older roleplayers I met at Strategy & Fantasy World. I would listen to people talk about chanbara films, Napoleonic tactics, and Norse mythology, all while hanging out in game stores and at library games days. I was introduced to a lot of different things simply because the then-new hobby of roleplaying attracted a very wide group of players with varied interests and everyone congregated in the same places.

As I've said repeatedly over the last couple of weeks, we didn’t always get along. In fact, we argued and, sometimes, we seemed to barely speak the same language. However, in those days, I often had no choice but to associate with people outside my immediate circle of comfort and taste and, because of that, I learned things. More than that, I grew.

Phil Dutré recently summed this up perfectly:

It’s also telling that gaming-at-large has become largely siloed and compartmentalized. In the 70s/80s/even 90s wargaming/roleplaying/boardgaming was still considered one big hobby (with a lot of crossovers), and one naturally came into contact with all sorts of people interested in various angles.

These days roleplayers and wargamers and board gamers almost seem to be different breeds, barely knowing of each other’s hobbies, let alone spending time with one another. My point is that, by having nowhere else to go, the early hobby brought together a lot of us weirdos and we learned stuff from each other. As I explained above, I was introduced to Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard through these people, just as I shared my love of ancient alphabets and languages, while others shared their love of history, mythology, philosophy, etc. I am literally the man I am today because I had no choice but to hang out with people I might otherwise not have. Today, I feel as if too many gamers self-select for people just like themselves in the narrowest senses. That's a shame, because having to learn to get along with people very different is a great way to improve oneself.

I wonder if part of the magic of the early hobby as I experienced it was precisely this unexpected mixing of oddballs. Even in the early 1980s, there simply wasn’t enough critical mass to allow subgroups to splinter off and form their own tightly curated communities. You couldn’t just find “your people” and ignore everyone else. You had to sit down with whoever showed up. The result was often volatile but also suffused with creative ferment. It was a fertile space where ideas, interests, and personalities collided, bearing strange fruit.

Don’t misunderstand. I’m not advocating for forced conviviality. The hobby is broader now and that’s a probably good thing in some respects. However, I do think something was lost when we all retreated to our own silos. When roleplayers stopped hanging out with wargamers and video gamers forgot that tabletop roleplaying even existed and when people began treating the games they play as lifestyle brands rather than as shared endeavors.

When we stopped being weird together.August 4, 2025

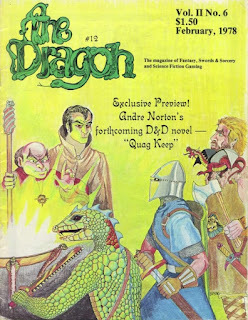

The Articles of Dragon: "The Lovecraftian Mythos in Dungeons & Dragons"

In honor of The Shadow over August, I thought I'd do something a little different with my weekly "The Articles of Dragon" series. Instead of continuing to highlight articles that I remember or that made a strong impression on me – good or bad – from my youth, I'm instead going to spend this month focusing on Dragon articles that touch upon H.P. Lovecraft, his Cthulhu Mythos, or related topics. Interestingly, nearly all these articles come from before I was even involved in the hobby, let alone reading Dragon regularly. While I can't say for certain why that might be, I have a theory that I'll discuss later in this post.

In honor of The Shadow over August, I thought I'd do something a little different with my weekly "The Articles of Dragon" series. Instead of continuing to highlight articles that I remember or that made a strong impression on me – good or bad – from my youth, I'm instead going to spend this month focusing on Dragon articles that touch upon H.P. Lovecraft, his Cthulhu Mythos, or related topics. Interestingly, nearly all these articles come from before I was even involved in the hobby, let alone reading Dragon regularly. While I can't say for certain why that might be, I have a theory that I'll discuss later in this post.

The "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" column is nowadays associated with Gary Gygax, but its first three appearances (starting with issue #11 in December 1977) were penned by Rob Kuntz. Furthermore, the second of these initial columns, entitled "The Lovecraftian Mythos in Dungeons & Dragons," is, in fact, largely the work of J. Eric Holmes with additions by Kuntz. In his brief introduction to the article, Kuntz explains that the material is intended to be "compatible with Dungeons & Dragons Supplement IV 'Gods, Demigods & Heroes'." It's also meant to satisfy both "Lovecraft enthusiasts" and those "not familiar with the Cthulhu cycle."

From the beginning, it's immediately clear that, despite its title, much of what follows in the article is not authentically Lovecraftian but owes more to August Derleth's idiosyncratic interpretation of HPL's work. For example:

The Great Old Ones of the Cthulhu Mythos are completely evil and often times chaotic. They were banished or sealed away by the Elder Gods.Now is not the time to relitigate the case of Lovecraft v. Derleth, which is a much more complex and nuanced discussion than many people, myself included, have often made it out to be. However, I bring this up simply to provide context for what follows. In February 1978, when issue #12 of Dragon appeared, Lovecraft scholarship was, much like that of Robert E. Howard, still in very much in its infancy, with the popular conceptions of both writers and their literary output still very much in the thrall of pasticheurs like Derleth, L. Sprague de Camp, Lin Carter, etc. With that in mind, we can look at the article itself.Holmes describes "only Lovecraft's major gods," namely, Azathoth, Cthulhu, Hastur, Nyarlathotep, Shub-Niggurath, Cthugha, Ithaqua, Yig, and Yog-Sothoth. These selections clearly show the influence of Derleth, who was very keen on Hastur, Ithaqua, and Cthugha, the last two of which were his own inventions. Each god is given an armor class, move, and hit points, along with magic, fighter, and psionic ability. I find these statistics really fascinating, as they're somewhat unimpressive by the standards of later editions of D&D, but were considered exceptionally powerful by the standards of OD&D, for which they were written. Cthulhu, for example, has only AC 2 and 200hp and fights like a 15th-level fighter.

Also described in the article are Byakhee, Deep Ones, the Great Race, the Old Ones, Mi-Go, and Shaggoths [sic]. They're described in the same way as the gods, using the same game statsistics. What I found interesting here is that Holmes suggests the Byakhee are more potent opponents than the Shoggoths, something my post-Call of Cthulhu brain wouldn't have concluded. From the vantage point of the present, that's what makes this article so fascinating: it's an artifact from a time before Chaosium's RPG was published and helped to popularize not just Lovecraft's creations but a particular interpretation of them. This article is an alternate presentation of those creations and, even if I disagree with parts of it, I appreciate its uniqueness.

Obviously, this article was published before 1980's Deities & Demigods, whose early printings included a different presentation of the Cthulhu Mythos. As a kid, my copy of the book was one of the later printings that didn't include this chapter (or that of Moorcock's Melnibonéan Mythos) and indeed I didn't even notice its absence until I was in college. My roommate has a copy of one of the early printings and I was flabbergasted when I saw its extra chapters. The saga of the inclusion and removal of the Cthulhu and Melnibonéan material from the DDG is well known, I think, so I won't repeat it here. However, I wonder if it left a sufficiently bad taste in TSR's mouth that Dragon would thereafter include almost no Lovecraft-related material in its pages for years after the event.

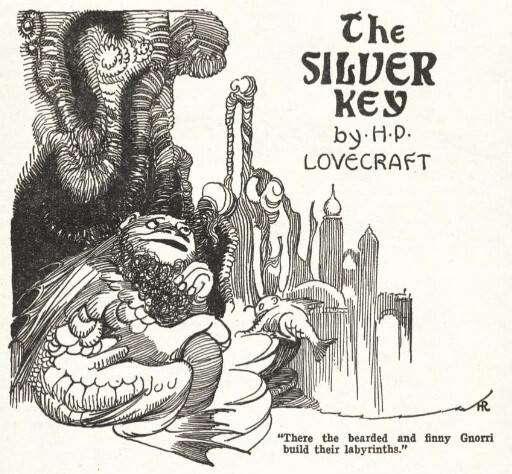

Hugh Rankin and "The Silver Key"

Though the covers of Weird Tales are usually more well remembered by history (for obvious reasons), it should be remembered that most of the stories published within the Unique Magazine had at least one accompanying illustration. So it is with H.P. Lovecraft's "The Silver Key," which featured this piece of artwork by Hugh Rankin.

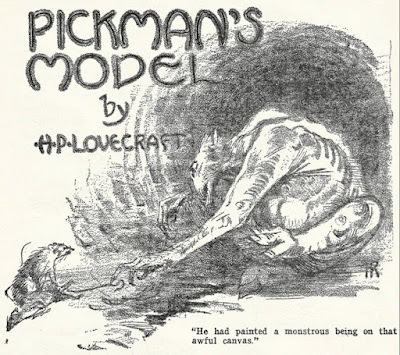

Rankin provided illustrations for dozens of stories during the 1920s and '30s, including many by Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. Perhaps his most significant one may be one from "Pickman's Model," depicting a ghoul.

Rankin provided illustrations for dozens of stories during the 1920s and '30s, including many by Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. Perhaps his most significant one may be one from "Pickman's Model," depicting a ghoul.

I can't say with absolute certainty that this is the first ever depiction of one of Lovecraft's ghouls in a publication, but I suspect that it is. That alone makes Rankin worthy of remembrance.

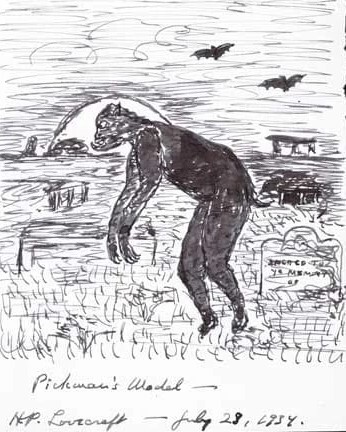

(I feel compelled to add Lovecraft's own drawing of a ghoul, which he drew in 1934, years after the publication of "Pickman's Model." I find it strangely charming.)

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers