James Maliszewski's Blog, page 10

August 3, 2025

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Silver Key

First published in January 1929 issue of Weird Tales, H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Silver Key” is an often overlooked but, in my opinion, important piece of his fiction. The story suffers in comparison to many of his more famous tales, because it contains no monstrous revelations, no ancient alien deities, no creeping madness. Instead, this is a deeply introspective and melancholic tale that straddles the line between fantasy and philosophical memoir. It’s a story less about horror and more about a different kind of loss: the loss of imagination, wonder, and a child's capacity to dream. These are topics that mean a great deal to me, as anyone who's read this blog for any length of time must know.

First published in January 1929 issue of Weird Tales, H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Silver Key” is an often overlooked but, in my opinion, important piece of his fiction. The story suffers in comparison to many of his more famous tales, because it contains no monstrous revelations, no ancient alien deities, no creeping madness. Instead, this is a deeply introspective and melancholic tale that straddles the line between fantasy and philosophical memoir. It’s a story less about horror and more about a different kind of loss: the loss of imagination, wonder, and a child's capacity to dream. These are topics that mean a great deal to me, as anyone who's read this blog for any length of time must know.The story's protagonist is Lovecraft’s recurring alter ego, Randolph Carter, now a man in his forties and burdened by years of disillusionment. In his youth, Carter had access to other realms through dreams of “strange and ancient cities beyond space, and lovely, unbelievable garden lands across ethereal seas." Alas, adulthood robbed him of that power. Now, “custom had dinned into his ears a superstitious reverence for that which tangibly and physically exists, and had made him secretly ashamed to dwell in visions.”

The crisis presented in "The Silver Key" is not merely fictional. Lovecraft was himself approaching 40 when he wrote the story. The 1920s had been a difficult decade for him. His marriage had collapsed, his brief sojourn in New York had ended in unhappiness and homesickness, and he had returned, somewhat defeated, to his beloved Providence. He had always found himself at odds with the modern world, disliking its commercialism and crudity, but the pace of change at that time seemed to him to have quickened. Lovecraft longed ever more for an idealized past, both personal and cultural, as a means to escape his dreary present. In “The Silver Key,” he gives poetic form to that longing.

What ultimately restores Carter’s access to the dream realms is the discovery of a literal silver key, hidden in the attic of his home. The key is a relic of youth, tied to his earliest experiences of fantasy. Using it, Carter is able to travel not merely through space or even into dreams, but into his own past. He once again becomes his younger self, at the age of ten, standing before a mysterious cave in the wooded hills outside of Arkham. The story ends with the suggestion that Carter has vanished from the adult world entirely, returning to his own youth, thereby regaining his ability to dream once more.

There is little action in “The Silver Key.” Much of the story is instead given over to philosophical reflection and autobiographical lament. It can thus be challenging reading for those expecting the grotesque thrills of Lovecraft's more well-known and celebrated tales. However, for those already familiar with his life and mind, "The Silver Key" may perhaps be his most revealing story. He wrote it not merely as fiction, but as a statement of belief:

“They had changed him down to things that are, and had then explained the workings of those things till mystery had gone out of the world. When he complained, and longed to escape into twilight realms where magic is moulded all the little vivid fragments and prized associations of his mind into vistas of breathless expectancy and unquenchable delight, they turned him instead toward the new-found prodigies of science, bidding him to find wonder in the atom's vortex and mystery in the sky's dimensions. And when he failed to find these boons in things whose laws are known and measurable, they told him he lacked imagination, and was immature because he preferred dream-illusions to the illusions of our physical creation.”

The longing for hidden marvels, for the “twilight realms” just beyond the veil of waking life runs through all of Lovecraft’s fiction, but rarely had he expressed it so directly or so wistfully. “The Silver Key” is not about terror, but about the creeping desolation of rationality untempered by wonder.

When I was younger, I didn't hold this particular story in very high esteem. However, as I trudge toward old age, I judge it much more favorably. I suspect that those attuned to the imaginative currents that run between early fantasy fiction and tabletop roleplaying games will likewise find that “The Silver Key” offers a potent metaphor. It is the story of a character who finds that the rules of the real world no longer satisfy him. So, he uses an inherited tool (a “key,” in the broadest sense) to reenter a realm where those rules don’t apply. It is a dream-quest, but one that begins not with a map or a monster, but with memory and imagination.

This story, and its sequel “Through the Gates of the Silver Key,” also serves to bind together the stories of Lovecraft’s so-called Dream Cycle and his broader cosmic mythos, turning Carter’s spiritual journey into something vaster and stranger. On its own, though, “The Silver Key” remains more intimate and perhaps more affecting. In it, Lovecraft invites the reader to consider that fantasy is not merely an escape but also a return, a recovery of something we all once possessed and may yet reclaim, if only we can remember the way.August 1, 2025

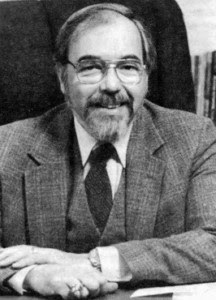

Interview: Mike Mason

One of first things I wanted to do with the Shadow over August series was to interview roleplaying game designers and creators who'd worked on RPGs influenced either directly or indirectly by the works of H.P. Lovecraft. Obviously, this meant reaching out to Mike Mason, the current creative director of Chaosium's venerable Call of Cthulhu, perhaps my favorite RPG to deal with Lovecraftian themes. Mike kindly agreed to answer my many questions about CoC, Lovecraft, and his own experiences with both.

1. What was your first exposure to H.P. Lovecraft’s writing and how did it shape your personal approach to horror and game design?

1. What was your first exposure to H.P. Lovecraft’s writing and how did it shape your personal approach to horror and game design?I was an eager reader of paperback horror stories in the 1970s, and I imagine I probably read at least one HPL short story during that time without realizing. A few years later in the early 1980s, I discovered the Call of Cthulhu RPG and HPL’s place in the creation of the Cthulhu Mythos, which then sent me off on a mission to track down HPL’s stories as well as those by August Derleth, Clark Ashton Smith, Ramsey Campbell, and so on. That was my first proper dive into Lovecraft’s writing. At that time in the UK, Granada had just published most of HPL’s works in a series of paperback books, which made it all very much easier to read them.

In reading these stories, I found these were not tales about murderers and crazed killers, or ghosts and goblins, which was the standard fare from popular horror anthologies the era, such as the Pan Horror series of books. The stories from the Lovecraft Circle were something different, dealing with bigger (cosmic!) themes, and were not really about petty human considerations (revenge etc.). The monsters were truly monstrous and unknowable (not mutated animals from atomic bomb testing) and alien. The books had strange books and lore which went well beyond anything I’d read before. All in all, this combination raised the Mythos stories above what I’d been used to reading, so they were more exciting, more involving, and made a deeper impression. It opens the door beyond “horror” fiction into “weird” fiction and I never looked back.

2. In what ways does Call of Cthulhu seek to capture the essence of Lovecraft’s cosmic horror that differs from other horror RPGs?

Being the first TTPRG to bring HPL’s creations into games, Call of Cthulhu was entirely different to every other RPG available. Here, the player characters were normal, average people, not superheroes or muscled-up barbarians, and so on. Here, the characters risked everything to save the day, with little more than a notebook and a pen, they delved into forbidden books for secrets, spells were deadly, and they could lose their minds when confronted with alien Mythos terrors. None of this was like bashing monsters to steal their treasures – the monsters in Call of Cthulhu were often more intelligent than the player characters, which added a new dimension, as the opponents were not only reactive to the players but also proactive. This dynamic shift elevated the game play and made the game stand out from the crowd.

Today, these same considerations continue to make Call of Cthulhu stand out and attract new people to play. I think Call of Cthulhu is the second most popular game on online platforms like Roll20, and it’s the most played game in Japan. The game’s easy to learn rules and enthralling game play captures the imagination and keeps people coming back for more.

The game is very flexible, so people can play all manner of horror tropes and mysteries with it – be it slow-burn cosmic revelations, one-night only survival horror, or pulpy two-fisted action – people are able to find and develop the style of game they desire with Call of Cthulhu, making it very accessible and broad in scope, unlike many other horror games that tend to narrow their focus down to a single style of play and a single type of experience.

3. Lovecraft’s protagonists are often passive or doomed. How has Chaosium adapted this narrative fatalism into something playable and engaging for decades?

3. Lovecraft’s protagonists are often passive or doomed. How has Chaosium adapted this narrative fatalism into something playable and engaging for decades?The game is about the players, who are usually the opposite of passive! We’re not retelling a HPL story – together, the players and their Keeper (game master) create a story – built up from the foundation of a pre-prepared scenario, which sets up a mystery or situation that the players engage with, and offers possible solutions to help guide the Keeper, and thereby the players, through to a satisfactory conclusion. The mechanics of the game mirror certain aspects from Cthulhu Mythos stories – humans are vulnerable, weak, and sensitive to the Mythos, which can both kill and corrupt their minds. There’s a downward spiral the player characters can find themselves on, however things are not set in stone and the characters can, sometimes, overcome and win the day with their minds and bodies intact.

But it is a horror game, so character deaths and awful in-game events do happen too – often to the great amusement of the other players! While it’s horror, it is a game and meant to be fun too. Each group of players finds the right level of game for them.

The key to the game is ensuring the players have the potential and possibility to win out, even though the odds are against them. This ensures the players have a chance to succeed, even if it’s minor victory. The players have to feel their actions can made a different, otherwise they become passive observers - and that’s no fun for anyone.

4. The Mythos has been diluted in pop culture to the point of parody in some circles. How does Call of Cthulhu resist that trend and maintain Lovecraft’s original tone?

There’s loads of advice we’ve written into our game books and the Call of Cthulhu rulebooks on exactly this subject– too much to write here! But, in essence – by staying true to the concept of the game and the stories its based upon – keep the horror horrific, ensure the player characters have something worth fighting for, and ensure that the Mythos (be it monsters, cultists, spells, and tomes) remain mostly mysterious and unknowable. From time to time, a situation in the game may be amusing and funny - that’s great, as the players let their guards down a little, which means the next scene, where they face some form of horror, can hit harder. The monsters in the game aren’t plushies!

5. What do you think Lovecraft would have made of Call of Cthulhu and its popularity? Do you think he would’ve approved or even played it?

I have no idea. HPL was a curious and strange person. I think the game would have amused him – seeing his creations sort of come to life, but then he’d probably get annoyed as we “weren’t doing Cthulhu right!” Or something like that.

6. What’s one underrated Lovecraft story you think deserves more attention, especially from Call of Cthulhu players?

6. What’s one underrated Lovecraft story you think deserves more attention, especially from Call of Cthulhu players?"The Music of Eric Zann." But, for players, I’d be pointed to "The Dunwich Horror," "The Call of Cthulhu," and At the Mountains of Madness. Perhaps also "The Colour Out of Space." But then you really should go read some other Mythos authors, like Ramsey Campbell, Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom, T.E.D. Klein’s The Ceremonies, and so many more!

7. What do you think the continued popularity of Call of Cthulhu says about the enduring appeal of Lovecraft’s vision, even a century later?

That cosmic horror is something that continues to be relevant to us – perhaps even more so than in HPL’s time. Lovecraft imagined humanity as insignificant in the greater cosmos. Everything we’ve seen and experienced over the latter 20th century and into the 21st has reinforced that idea. Once, we believed the Earth was the centre of the universe – now, we actually realize how small our planet is in relation to everything else, and how precious our planet is – it’s the only one we know that sustains life. Thus, the fear of losing it all, whether by cosmic whim or self-destruction, continues to impact upon us. The world has dramatically changed since Lovecraft’s time and our collective fear is so much greater now. Lovecraft foresaw a glimpse of that fear and channeled it into his stories.One Month In

It’s now been a month since I launched Grognardia Games Direct, my Substack newsletter dedicated to my various RPG projects, most notably Thousand Suns, Secrets of sha-Arthan, and anthologies of Grognardia’s most enduring and influential posts.

Substack is a very different platform from Blogger. It's newer, more streamlined, and still unfamiliar in some ways, but I’ve enjoyed the process of learning its ins and outs. After just 31 days, I feel I’ve found a productive rhythm, one that’s helped me focus my creative energies more effectively than I have in some time.

I’m grateful to everyone who’s already subscribed. I’m within spitting distance of 500 subscribers, an encouraging milestone for a new Substack or so I’m told. Of course, I’d love to see that number grow. The more readers I have, the more feedback I receive, which is especially valuable in the case of Secrets of sha-Arthan. Unlike my other projects, it’s a wholly new endeavor, not a continuation of earlier work, and outside perspectives are particularly helpful as I shape its direction. If you’ve enjoyed my past RPG writing, I hope you’ll consider taking a look.

I’ll admit, I was initially reluctant to start a Substack, despite encouragement from friends. My chief concern was that it might distract me from Grognardia. As much as I wanted to explore new territory, I had no intention of neglecting this blog or the community that’s grown up around it.

To my surprise, just the opposite has happened. Rather than pulling me away from Grognardia, the newsletter has sharpened my focus on it. In writing for both venues, I’ve written more – and, I think it’s fair to say, better – posts here than I have in quite some time. For whatever reason, working on both platforms has been creatively energizing. I feel more in tune with my work now than I have in months, maybe even years. Whether that’s apparent to readers, I leave for you to judge.

In the meantime, I appreciate your patience with my occasional reminders about new Substack posts I believe might be of interest to Grognardia’s readers. I’m having a great time over there and I’d like to share that enthusiasm more broadly.July 31, 2025

That Is Not Dead

There are certain names in the history of imaginative literature that echo far beyond their own works, names that, like half-heard whispers in the dark, seem to crop up again and again in unexpected places. H.P. Lovecraft is assuredly one of those names.

There are certain names in the history of imaginative literature that echo far beyond their own works, names that, like half-heard whispers in the dark, seem to crop up again and again in unexpected places. H.P. Lovecraft is assuredly one of those names.His peculiar blend of cosmic dread, archaic prose, and invented mythologies may not be to everyone’s taste, but it’s impossible to deny the depth of his impact. You find it not just in the realm of horror, where Lovecraft’s long been a fixture, but in fantasy, science fiction, RPGs and video games, heavy metal music, and even more arcane corners of contemporary popular culture. Entire subgenres owe their existence to his worldview; entire hobbies have been shaped, however subtly, by his conception of reality as a frail, human construct poised over a fathomless abyss.

The The Shadow Over August is, as I previously announced, a month-long meditation on Lovecraft's influence. I intend this series as neither a canonization nor a condemnation of HPL, but as a recognition of the indelible legacy left by the Old Gent from Providence. Regular readers of this blog know that I’ve long been fascinated by the threads Lovecraft wove into the broader tapestry of nerd culture, such as its obsession with "lore," its joy in piecing together fragmented bits of information, and the sense of awe before vast, impersonal forces. You can clearly see that influence in the rules of Call of Cthulhu, the bleakness of Alien, and the adventures of Mike Mignola's Hellboy, among many more. Even if you’ve never read a word of Lovecraft, you’ve probably encountered a tentacle or two in your travels.

Lovecraft’s legacy is not a monolith and this series reflects that. I’ve invited a number of others to participate – some who admire his work, some who challenge it, and some who do both. Disagreement is part of any healthy conversation, especially one about a figure as contradictory and complicated as Lovecraft. If we’re serious about understanding his place within popular culture, we have to reckon with all of it and do so from a perspective of curiosity, honesty, and critical engagement. Only by approaching Lovecraft in his full complexity can we appreciate the depth of his impact and understand why his legacy continues to provoke such passionate discussion nearly ninety years after his death.

So think of the The Shadow Over August as a guided expedition into the cyclopean landscape of Lovecraft’s legacy. I have no plans to map every inch of it, of course, but I hope to visit not just its well-trodden landmarks but some of its overlooked corners as well. Over the coming month, I’ll be sharing interviews, commentary, old projects, literary reflections, and more. Whether you’re a longtime devotee of Ech P'i El or a curious newcomer, I hope you’ll join me as we explore the shadow that still lingers over so much of the imaginative work we hold dear.On the Advantage and Disadvantage of Nostalgia

There’s a familiar refrain I hear often, particularly online, when someone expresses admiration for the early years of the roleplaying hobby. Such admirers are “blinded by nostalgia,” they say. They're clinging to a past that never really existed, refusing to acknowledge the supposedly self-evident truth that “things are just better now.” It's a common accusation, one that I've been hearing since the dawn of the Old School Renaissance almost twenty(!) years ago. Frequently, the accusation comes with the smug certainty of progress, for surely only a fool would prefer the clunky rulebooks, crude illustrations, and amateur layout of the 1970s to the sleek, professional products of today?

Let me be clear: I am nostalgic – proudly so – but I am also not blind.

Nostalgia, like memory itself, is selective. It remembers what it values, sometimes to the exclusion of what it should not forget. That is both its virtue and its danger. If I may be permitted to indulge briefly in my academic training, I'm reminded of Friedrich Nietzsche's 1874 work On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life, in which he cautioned against what he called “antiquarian” history. Antiquarian history, according to Nietzsche, is the kind that reveres the past so much it embalms it, turning it into a shrine rather than a source of life. At the same time, Nietzsche also warned against what we might now call presentism, which is to say, the uncritical acceptance of the Now as inherently superior, merely because it is newer.

In the context of RPGs, nostalgia often gets a bad rap. It’s treated as a distortion field, a kind of mental defect that prevents one from recognizing “how far we’ve come.” This perspective assumes that progress is inevitable, uniform, and always desirable. I simply don't buy that. I don't think it's true in art or the wider culture more generally, so why should it be true in the case of roleplaying games?

When properly tempered, what nostalgia offers is a connection to formative experiences, the kind that shaped our imaginations and ways of thinking. When I return to In Search of the Unknown or the three little black books of Traveller, I don’t do so out of some longing for childhood simplicities. I return because those works still mean something to me. They still inspire. Their limitations are part of their magic. The blank spaces, unspoken assumptions, and rough edges still invite interpretation and invention today as they did when I first read them decades ago.

Of course, nostalgia can deceive. It can sand off the roughness, forget the arguments over rules, and the unexamined biases of early texts. It can create a false Golden Age that never really existed. That is its disadvantage and it’s a very real one. No less real is the disadvantage of neophilia, the mindless embrace of the new for its own sake, which too often confuses polish with depth and complexity with quality.

We must also be honest about the social dynamics of the early hobby. It could be insular and off-putting to some. Though this was not my own experience, I know from talking to others that some of those early communities were not especially welcoming. Consequently, some of the changes in the contemporary RPG scene may be for the better. To the extent that the hobby today is more accessible than it might have been in the past, that's worth celebrating. At the same time, we must take care that, in acknowledging these improvements, we do not simply condemn the past as unworthy of our continued affection.

The truth is, the early hobby, the one I entered as a kid, didn’t just introduce me to games. It cultivated in me a lifelong love of history, philosophy, languages, art, and literature. It did this not in spite of its amateurishness, but often because of it. Those early games were demanding. Their rules were opaque. Their references were obscure. However, rather than alienating me, their opacity invited me to learn more – to dig deeper, to grow. That’s not something to be dismissed lightly.

Certainly, there were problems in the past, just as there are different problems today. That’s life. Every era has its strengths and its blind spots. The trick is not to pretend otherwise, but to recognize that nostalgia, when used well, can be a guide to what mattered and what still matters.

There’s nothing inherently virtuous about liking new things, just as there’s nothing inherently foolish about loving old ones. If anything, the true sin is not nostalgia but refusing to examine why we prefer what we prefer, pretending that our tastes are self-evidently superior, whether rooted in the past or in the present. In the end, nostalgia, like history, should be used for life, not against it. It should deepen our appreciation, not ossify our preferences. It should connect us to a tradition we care about, not imprison us within it. I cherish the early years of the hobby not because they were perfect, but because they were alive with possibility – and that possibility remains.July 30, 2025

Table of Contents

Table of Contents by James Maliszewski

A Proposed TOC for Volume 1 (Whatever it's called)

Read on SubstackJuly 29, 2025

Retrospective: Vampire: The Masquerade

Continuing with my recent trend of posts that have proven inexplicably contentious, I have decided to do a Retrospective post for White Wolf's Vampire: The Masquerade, a game considered by some fans of old school RPGs to represent a major point at which the hobby took a seriously wrong turn. My own opinion of the matter is considerably more nuanced than that, but I agree that the publication of Vampire in 1991 does mark an important hinge point in the evolution of roleplaying games.

Continuing with my recent trend of posts that have proven inexplicably contentious, I have decided to do a Retrospective post for White Wolf's Vampire: The Masquerade, a game considered by some fans of old school RPGs to represent a major point at which the hobby took a seriously wrong turn. My own opinion of the matter is considerably more nuanced than that, but I agree that the publication of Vampire in 1991 does mark an important hinge point in the evolution of roleplaying games.If, like me, your introduction to RPGs was through Dungeons & Dragons, Vampire: The Masquerade felt like it had come from another world. Where the focus of D&D was on adventure broadly defined, Vampire was about mood, metaphor, and personal horror. It didn’t merely offer a new set of rules, but a fundamentally different vision of what roleplaying games could be. It was brash, stylish, and theatrical in a way that felt almost confrontational to the sensibilities of "traditional" roleplaying games – and I suspect that was intentional.

Even if you didn’t play Vampire – and I didn't and still haven't – you couldn’t ignore it. By the mid-1990s, Vampire was everywhere: at conventions, in hobby shops, and in the imaginations of a younger generation of gamers for whom roleplaying didn’t begin with The Keep on the Borderlands, but in the nightclubs and dark alleys of White Wolf's "gothic punk" setting. Whatever else you might say about it, Vampire captured the Zeitgeist with almost supernatural precision. The Cold War was over, cyberpunk had gone corporate, and angsty antiheroes were ascendant in pop culture. Vampire gave roleplayers a way to inhabit that mood and make it their own.

Looking back, the game’s presentation probably played a big part in its success. The rulebook looked very different from those of other games on the market. It was filled with fiction, quotes from Schopenhauer and the Indigo Girls, brooding black-and-white artwork, and a relentless focus on theme. Its mechanics, such as they were, often took a backseat to emotion, identity, and esthetic. Character creation prioritized personality, inner conflict, and one’s place within a secretive, decaying society. The World of Darkness, as it came to be known, was more than just a setting. It was a tone, a posture, and a subculture, for good and for ill.

For players of old school D&D or Traveller, used to thinking of characters as problem-solvers and adventurers, Vampire was jarring. Here, the emphasis wasn’t so much on overcoming external challenges, but internal ones. What mattered wasn’t what your character could do, but who he was, what he felt, and how far he’d fall into monstrosity. The oft-parodied “angsty vampire with a katana" stereotype, while real, obscures just how radical this idea was at the time. Vampire: The Masquerade was – or at least aspired to be – a roleplaying game where introspection and tragedy weren’t just permissible but central.

From a mechanical standpoint, Vampire was a bit of a mess. Its Storyteller system was vague, inconsistent, and sometimes begged the question of whether mechanics mattered at all. Of course, it wasn’t designed to support dungeon delving or tactical combat. Instead, it aimed instead to foster collaborative storytelling, character drama, and social intrigue. For many players of the game, it more than succeeded in this aim and its approach to roleplaying soon became not only widespread but, I would argue, the norm.

The game also changed who played RPGs. Vampire brought in a lot of people who'd never played a roleplaying game of any kind, thereby changing the face of the wider hobby. Its gothic, romantic esthetic was attractive to these newcomers in a way that dragons, starships, and mutants never could be. Beyond that, Vampire inspired live-action roleplaying on a scale previously unseen and encouraged a style of play that emphasized character, emotion, and interpersonal drama over puzzles and tactical challenges. Like it or not, Vampire's impact was immense – to the point where the game was once a serious challenger to D&D's hegemony.

From the perspective of old school play, Vampire remains, in most respects, an alien creature. It’s driven more by narrative intention than by exploration or open-ended play. The referee – sorry, Storyteller – is often expected to have a plot and characters are meant to fit into it. That almost certainly rankles those of us for whom the oracular power of dice and emergent play are the acme of roleplaying. Even so, it’s impossible to deny what Vampire accomplished. It dared to be something different and, by doing so, it opened doors. Whether or not you liked what was on the other side, you had to admit it was impressive that someone found a key.

It’s fashionable nowadays to treat Vampire: The Masquerade with irony or to blame it for the sins of later trends, like over-emoting, railroading, or the tyranny of the tragic backstory. While there's more than a little truth to these jabs, I also think it does the game and its influence a disservice. Much like Dungeons & Dragons itself, Vampire was a lightning-in-a-bottle moment that was simultaneously bold, flawed, and genre-defining. It clearly gave roleplayers, especially younger ones, something they were craving, even if they didn't quite realize it at the time. Even though I was never a huge fan of the original game – I liked several later World of Darkness games better – there's no denying its power.July 28, 2025

REPOST: The Articles of Dragon: Physics and Falling Damage

And so we return to falling damage once again.

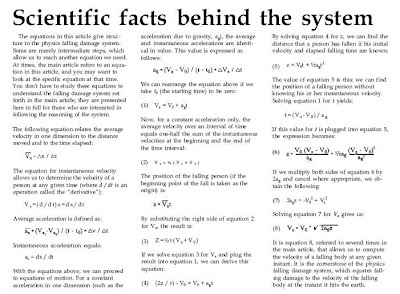

And so we return to falling damage once again.Issue #88 (August 1984) presents a lengthy article by Arn Ashleigh Parker that uses physics -- complete with equations! – to argue that neither the as-published AD&D rules nor the purportedly Gygaxian revisions to same from issue #70 adequately reflects "the real world." Here's a scan of some of the equations Mr Parker uses in his article:

I'm sure it says something about my intellectual sloth that my eyes just glaze over when I see stuff like this in a roleplaying game. The very idea of having to understand acceleration, terminal velocity, and the like to arrive at a "realistic" representation of falling damage is bizarre enough. To do so as part of an argument against earlier rules is even more baffling. D&D's hit point system doesn't really stand up to extensive scrutiny if "realism" is your watchword. In my opinion, devoting so much effort to "prove" that terminal velocity is reached not at 200 feet as in the Players Handbook system or at 60 feet as in the revision but at 260 feet is a waste of time better spent on making a new monster or a new magic items – things that actually contribute meaningfully to fun at the game table. But I'm weird that way.

I'm sure it says something about my intellectual sloth that my eyes just glaze over when I see stuff like this in a roleplaying game. The very idea of having to understand acceleration, terminal velocity, and the like to arrive at a "realistic" representation of falling damage is bizarre enough. To do so as part of an argument against earlier rules is even more baffling. D&D's hit point system doesn't really stand up to extensive scrutiny if "realism" is your watchword. In my opinion, devoting so much effort to "prove" that terminal velocity is reached not at 200 feet as in the Players Handbook system or at 60 feet as in the revision but at 260 feet is a waste of time better spent on making a new monster or a new magic items – things that actually contribute meaningfully to fun at the game table. But I'm weird that way.Amusingly, issue #88 also includes a very short rebuttal to the above article by Steve Winter. Entitled "Kinetic Energy is the Key," Mr Winter argues that, if one considers the kinetic energy resulting from a fall, you'll find that its increase is linear, thus making the original system a surprisingly close fit to the "reality." He makes this argument in about half a page, using only a single table (albeit one that draws on the earlier equations). While I agree with Winter that the original system is just fine for my purposes, it's nevertheless interesting that the author also makes his case on the basis of physics, as if the important point is that AD&D's rules map to facts about our world. It's a point of view I briefly held as a teen and then soon abandoned, for all the obvious reasons. Back in 1984, though, this was the height of fashion and many a Dragon article proceeded from the premise that the real world has a lot to teach us about how rules for a fantasy roleplaying game ought to be constructed ...

July 27, 2025

In Defense of Bob

His name wasn’t really Bob, but I’m calling him that for the purposes of this post, on the extremely unlikely chance that he’s still out there somewhere. It’s been decades and I doubt he’d even remember me. Still, I don’t want to be cruel; there's already plenty of that online. Moreover, that's not my purpose here.

His name wasn’t really Bob, but I’m calling him that for the purposes of this post, on the extremely unlikely chance that he’s still out there somewhere. It’s been decades and I doubt he’d even remember me. Still, I don’t want to be cruel; there's already plenty of that online. Moreover, that's not my purpose here.Bob was a teenager I’d see from time to time at hobby stores and at game days at the local libraries in the early 1980s. Like many of us back then, Bob was awkward, intense, and very passionate about the things he loved. For him, one of those things was World War II.

In those days, this was hardly unusual. I’m not sure people younger than a certain age realize just how omnipresent World War II still was in the cultural imagination of the time, even though it had ended more than three decades beforehand. This was especially so in the years after Vietnam, when America seemed unsure of what to make of its recent history, World War II stood apart. According to its conventional presentation, it was “the Good War,” the one where we knew who the bad guys were. Toy aisles were filled with green army men and gray tanks. TV reruns still showed Combat! and Rat Patrol. There were countless paperbacks, comics, movies, documentaries, and model kits. Nearly everyone had at least one older relative or neighbor who’d been “over there.”

So, Bob’s obsession wasn’t strange, not in context. What was unusual, even among kids interested in World War II, was the depth of his knowledge. Bob didn’t just know the basics. He could name operations and battles most people had never heard of. He knew the names of generals and details about their lives. He could tell you how a Panther tank compared to a Sherman and why Rommel’s tactics in North Africa were studied in military academies around the world. He was, for a teenager, astonishingly well-informed.

Bob was also socially tone-deaf. He didn’t always know when to stop talking, particularly when the subject was German armor or the Eastern Front. Even back then, people would roll their eyes when Bob launched into another lecture about Stalingrad. Mostly, though, we just let him do his thing. He was weird and so were we. More importantly, he played RPGs. That was enough.

Nowadays, I'm sure Bob would be viewed differently. People might hear him talk about German tanks or Guderian’s campaigns and jump to conclusions. They might assume he was some kind of Nazi sympathizer or apologist. That’s not how I remember him at all. Now, I didn’t know Bob well. I didn't have a window into his soul, but I never once got the impression he admired Hitler or fascism or anything like that. He was just a very nerdy teenager who’d gotten fixated on a complex and highly documented period of history. He liked the minutiae. If anything, he treated World War II the way other kids treated baseball, obsessively reciting rosters and statistics no one else cared about.

Bob was not a threat. He wasn’t trying to smuggle dangerous ideas into the games he played. He was just Bob – one of us. He was weird, annoying, and even brilliant in his own narrow way. I feel like it's important to point this out, not to excuse anyone, but to defend the idea that not every interest held by socially awkward people should be a moral test. Likewise, not every off-note conversation from forty years ago is a sign of hidden malice. We were all a little odd in those days; that’s probably what brought us together.

I bring all this up in light of last week's post about my recollections of how odd people of all stripes seem to get along in the hobby of my youth. Back then, the hobby felt – to me anyway – like a patchwork of eccentrics, whether they were metalheads, stoners, bookworms, would-be game designers, history buffs, or, yes, kids like Bob. We didn’t all get along. We didn’t all like the same things. Yet, we shared a love of imaginative play and we didn't care about much of anything else.

Was that everyone's experience back in the day? I highly doubt it, but I also doubt that the worst examples someone could dredge up from those times was typical either. I suspect the truth, as it so often is, lies somewhere in the middle. Judging from the arguments in the comments to last week's post, I suppose I was naive in thinking we could get back to just having fun with RPGs the way I used to as a kid.

I don’t know where Bob is now or what he became. Wherever he is, I hope he has a group of friends with whom he can roll some dice without being judged too harshly for his idiosyncrasies. He deserves that much.

So do we all.July 26, 2025

Architect of the Modern Imagination

E. Gary Gygax died on March 4, 2008, at the age of 69. Just over three weeks later, this blog published its first post. That was no coincidence.

Though I’d begun reflecting seriously on old school Dungeons & Dragons in late 2007, shortly before I joined the ODD74 forums, it was Gygax’s death that galvanized me. His demise marked the end of an era and, for me, the beginning of a personal project to explore, celebrate, and better understand the legacy of the game he helped bring into the world.

Today would have been his eighty-seventh birthday. In light of that, I want to pause and remember the life of a man who, though I never met him, profoundly shaped my own. More than that, he shaped the lives of millions, often in ways so pervasive we no longer recognize their origin.

Volumes have been written about Gygax's career, his eccentricities, his talents, and his failings. Seventeen years later and more than half a century since the release of Dungeons & Dragons, it’s time to say something both bold and, I believe, undeniably true: Gary Gygax was one of the most consequential cultural figures of the 20th century.

That may sound hyperbolic, even to readers of this blog. Gygax didn’t lead a nation, win a war, or cure a disease. What he did do was co-create a game that fundamentally reshaped the imaginative landscape of the modern world. Just as significantly, he popularized it. Through passion, persistence, and a gift for theatrical self-promotion, he took a niche idea, half rooted in wargaming, half in pulp fantasy, and gave it structure, rules, and language. He turned it into something accessible, repeatable, and endlessly expandable. He turned it into Dungeons & Dragons.

In this, Gygax's closest analog is probably Walt Disney. Neither man invented his medium. Animated film predates Disney, just fantasy games predate D&D. However, both men synthesized their influences into a new form and then made it a fixture of mainstream culture. Disney did it with cartoons. Gygax did it with dungeons, dragons, and rulebooks put together in his kitchen.

From that small seed, a global phenomenon grew.

If that seems overstated, consider where we are in 2025. Playing Dungeons & Dragons is no longer a fringe entertainment. It is a cornerstone of pop culture. It’s referenced in popular films and prestige television. It inspires bestselling novels, hit video games, and streaming series. Its influence is everywhere, from the language of "hit points" and "levels" to the way we talk about our personalities in the shorthand of alignment. "I'm a chaotic good introvert," someone might say, without either irony or the need for explanation.

None of that was inevitable. Without Gygax, it’s possible that some form of roleplaying game would have come into being, but would it have appeared in 1974? Would it have spread as quickly or inspired so many imitators? Would the worlds of gaming and fantasy fiction look anything like they do today?

Gary Gygax’s true legacy is more than a single game. It’s a mode of thinking, a grammar of imagination. It’s the idea that you don't have to be content with simply reading about fantasy adventures; you can go on one yourself. He gave us the tools to build our own worlds, to share them with friends, and to lose ourselves in collective acts of creativity.

That’s not a footnote to cultural history. That is cultural history.

So yes, Gary Gygax deserves to be remembered and indeed celebrated as a visionary, a pioneer, and one of the key figures in shaping how we imagine and play in the modern age.

Happy birthday, Gary. You didn’t just help us imagine new worlds. You showed us how to make them.James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers