James Maliszewski's Blog, page 13

July 9, 2025

The Shape of the Heavens

Sing, Muse, of the noble dodecahedron, twelve-faced and true,

So oft neglected in the clattering chorus of polyhedral dice!

Raise now a hymn to the least loved of gaming’s solids.

Pity the poor d12! Always the bridesmaid, never the bride. The d20, that lumbering golf ball of chance, sees far more use, while even the d4, a caltrop in disguise, is remembered (if only by the soles of our feet). But the d12? Forgotten. Neglected. Dare I say underappreciated?

Yet, what a die it is! Twelve equal pentagonal faces, each meeting at broad angles. Indeed, the dodecahedron is the shape Plato associated with the heavens themselves, the cosmos rendered in acrylic or resin. According to some ancient sources, the gods used d12s when rolling for Fate. Who needs the Pythia when you’ve got precision-milled polyhedra?

Physically, the d12 may be the most satisfying die to hold. Substantial without being bulky. Perfectly symmetrical. It rolls with purpose. It doesn’t skitter like a d4 or overdo it like percentiles. The d12 knows what it’s about. It rolls once and rolls well. There’s something reassuring in that.

But what is it usually asked to do? Calculate long sword damage against large opponents. Serve as the hit die for the barbarian. It's the gaming equivalent of being called in to move a couch. Even the d10, that irregularly-shaped interloper, has muscled its way to the top of the pile, if only for percentile rolls. The d12? Banished to the edge of the table, like some exiled aristocrat.

I've done my part to rectify this injustice in Thousand Suns, where the d12 takes its rightful place at the center of the action. Why? Because it deserved better. Because it felt right. Because when I picture futuristic exploits in a sprawling interstellar empire, I don’t want to roll a pyramid or a cube. I want a Platonic solid whose geometry is touched by the divine. I want the Golden Ratio embedded in plastic.

So, here’s to the d12: noble, overlooked, and elegant. May we find more uses for it at our tables – and more excuses to hear its satisfying clatter. After all, if it's good enough for the heavens, it ought to be good enough for us.

The Best of Grognardia

With that in mind, I’ve just posted a sort of follow-up to last week’s Preserving Grognardia, where I share more of my current thoughts and early plans for a possible Grognardia anthology (or even a series of them). If that sounds intriguing, you can check it out via the link below.

The Best of Grognardia by James Maliszewski

What Are You Favorite Posts?

Read on SubstackJuly 8, 2025

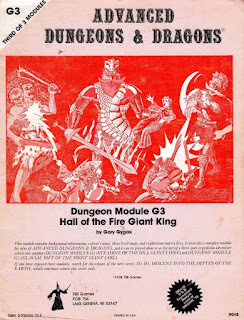

Retrospective: Hall of the Fire Giant King

Like its predecessors, Steading of the Hill Giant Chief and The Glacial Rift of the Frost Giant Jarl, Hall of the Fire Giant King (AD&D module G3) casts the player characters in the role of elite agents tasked with stopping a wave of giant-led attacks against civilized lands. At first glance, G3 seems to follow the familiar pattern established by the earlier modules: a dangerous foray into the stronghold of a powerful giant chieftain, bristling with guards, traps, and treasure. However, Hall of the Fire Giant King subtly but significantly shifts the tone and scope of the series. In the volcanic fortress of King Snurre Ironbelly, the stakes begin to change. The fire giants are stronger, more disciplined, and clearly part of a larger, more organized force. Most crucially, they are not acting alone. Hidden deep within their halls are strange and powerful allies – the drow.

The appearance of the drow, mysterious and only briefly described here, marks a pivotal moment not just in the G-series but in the history of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons itself. This is their first true introduction into the game, beyond a cursory reference in the Monster Manual, and it opens the door to something far more expansive. In retrospect, the drow are the most significant legacy of this module and G3 is the seed from which they (and the subterranean realm from which they come) would grow. The drow would, of course, go on to take center stage in the celebrated D-series (Descent into the Depths of the Earth, Shrine of the Kuo-Toa, and Vault of the Drow) and in Queen of the Demonweb Pits. While those later adventures are better known and more ambitious, it is here, in Hall of the Fire Giant King, that the broader arc first begins to unfold. Gary Gygax’s decision to place these enigmatic figures behind the scenes of the giants’ uprising was a masterstroke, one that quietly expanded the narrative scope of what a D&D adventure could be.

In terms of presentation, Hall of the Fire Giant King also reflects the transitional state of adventure design in 1978. Like its predecessors, it was originally created for tournament play, which explains both its high level of difficulty and its emphasis on tactical combat. There is little in the way of exposition or character development. The fire giants certainly have motivations, but Gygax rarely dwells on them. Instead, they exist primarily as obstacles to be overcome. Much of the module consists of populated chambers, heavily guarded halls, and defensible choke points, all spaces presented for intense, deadly conflict. Success demands planning, coordination, and no small amount of caution. This is adventure design in its raw, uncompromising form, rewarding player skill and punishing incaution.

Yet even within this sparse and utilitarian framework, there are hints of something more. Secret doors lead to hidden levels. Mysterious altars and magical portals suggest the influence of otherworldly forces. Cryptic symbols and strange alliances point to deeper mysteries. Gygax may not linger on these details, but their presence invites speculation and discovery, encouraging referees to build upon them. In this way, G3 foreshadows the more expansive and narrative-driven modules to come, not only the D-series, but later experiments in long-form storytelling such as Dragonlance in the 1980s and the “adventure path” format popularized by Dungeon magazine in the early 2000s. Hall of the Fire Giant King doesn't tell a story in that modern sense, but it gestures toward one and that gesture proved enormously influential.

From the vantage point of the present, G3 may seem narrower in scope or rougher in execution than the adventures it leads into. I actually think that's part of its importance. As both the climax of the "Against the Giants" trilogy and the prelude to the D-series, it bridges two different modes of adventure design: the brutal, self-contained dungeon crawl and the broader, interconnected campaign. Without Hall of the Fire Giant King, the drow might never have become one of the game’s signature antagonists. More broadly, the ambition and structure of later adventures might have taken a very different form without this model to follow.

In the end, I feel Hall of the Fire Giant King is best appreciated not just as the finale of the G-series but as a threshold. It marks a turning point where the possibilities of adventure design began to expand, where dungeon crawls started evolving into epics. With its hidden depths, emergent story, and quiet worldbuilding, Gygax showed that even a tournament module could hint at vast, subterranean empires and the demon-goddess who ruled them. Its influence is subtle but foundational and its legacy lives on in the continuity it helped establish across TSR’s early adventures and the ambitions it inspired in generations of designers to follow.July 7, 2025

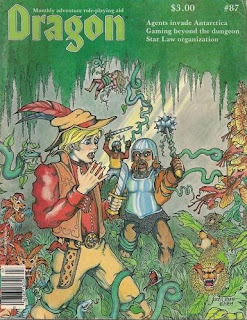

The Articles of Dragon: "Luna: A Traveller's Guide"

I subscribed to Dragon from issue #68 (December 1982) till #127 (November 1987). During that five-year period, my favorite section of the magazine – by far – was the Ares Section, which appeared in its pages each month from issue #84 (April 1984) until issue #111 (July 1986). That's because the Ares Section, as its name suggests, was devoted entirely to science fiction roleplaying games and, being even more of a sci-fi nerd than I am a fantasy one, this held a great deal of appeal for me. As you'll know doubt learn over the course of the coming weeks, many of my favorite and most beloved articles of Dragon appeared in the Ares Section and left a lasting impact on both my memories of the magazine as a whole and one my youthful imagination.

I subscribed to Dragon from issue #68 (December 1982) till #127 (November 1987). During that five-year period, my favorite section of the magazine – by far – was the Ares Section, which appeared in its pages each month from issue #84 (April 1984) until issue #111 (July 1986). That's because the Ares Section, as its name suggests, was devoted entirely to science fiction roleplaying games and, being even more of a sci-fi nerd than I am a fantasy one, this held a great deal of appeal for me. As you'll know doubt learn over the course of the coming weeks, many of my favorite and most beloved articles of Dragon appeared in the Ares Section and left a lasting impact on both my memories of the magazine as a whole and one my youthful imagination.

One of the interesting things the section's editors occasionally did was run series in which a topic was given an article devoted to showing how that topic was handled in a particular science fiction RPG. One of the first one (and one of the best) concerned Earth's satellite, the Moon. Over the course of five articles, the Ares Section treated readers to depictions of the Moon in Gamma World, Star Trek, Space Opera, Other Suns, and, finally, Traveller, the last of which is the subject of today's post. I found all these articles incredibly interesting, though, as you'd expect, the one for Traveller, appearing in issue #87 (July 1984), is the one most dear to my heart.

To begin with, the article in question was penned by none other than the creator of Traveller, himself, Marc W. Miller. That immediately lent it a high degree of importance in my young eyes. Miller was to Traveller as Gary Gygax was to Dungeons & Dragons: the final authority. Consequently, when his byline appeared on an article – which was rare, much rarer than Gygax – I took it very seriously. I took "Luna: A Traveller's Guide" as absolutely official and duly incorporated the information contained in it into my Traveller adventures and campaigns.

Furthermore, the article described the Moon – or Luna, as it's called here – within the context of GDW's Third Imperium setting. For those unfamiliar with the intricacies of that setting, Earth (or Terra) is the homeworld of the Solomani, the "original" human race that evolved naturally on that planet. All other human races, like the Vilani and the Zhodani, descended from Terran humans transplanted to other worlds by the mysterious Ancients, a technologically advanced alien race that once roamed the galaxy 300,000 years ago. Terra and Luna are currently under military occupation by the Third Imperium, a consequence of losing the Solomani Rim War more than a century ago, when the Solomani attempted to secede from the Imperium.

It's against this backdrop that Miller presents his vision of Luna as a lightly populated scientific colony in orbit around the homeworld of humaniti (as Traveller spells the name of the human race taken as a whole). Miller provides information on the population and demographics of the Moon, its settlements and transportion, its politics, and, of course, its history. The latter is especially interesting, as it helps to provide additional details about the deep background of the Third Imperium setting, such as the Solomani discovery of jump drive and its role in the Interstellar Wars against the Vilani First Imperium. As a teenager, this was catnip to me, both as a Traveller fan and as someone who'd grown up in the afterglow of the 1969 Moon landing.

I loved it all, of course, but, re-reading the article now, I do wonder what people not as immersed in the Third Imperium setting would have thought of it. For example, there are lots of adventure seeds throughout the article, but almost all of them tie into some aspect of imperial history or some other unique aspect of the Third Imperium. That's not a unique "problem" to this article; the other treatments of the Moon are similar in this regard. However, it's something I noticed now and started to think about: how does one present an adventure locale that simultaneously leverages its connection to a particular setting while also providing something of interest/use to people who don't use or know much about that setting? This is a question I still struggle with to some degree and I suspect I'm not the only RPG writer who does so.But, as I said, I didn't even notice it at the time. I was simply excited to learn more about the Moon in one of my favorite imaginary settings. From that perspective, "Luna: A Traveller's Guide" gave me everything I wanted and more.

What's Next for Thousand Suns?

The Return of Pulp Fantasy Library?

Starting in August, I plan to revive the Pulp Fantasy Library series – at least for a month – as a bit of a trial run. Longtime readers will recall that this series was once a mainstay of Grognardia, where I looked at older works of fantasy, science fiction, and related media that either directly influenced or ran parallel to the early days of roleplaying. For this trial revival, I’ll be posting four entries, one for every Monday in August, each devoted to a story by H.P. Lovecraft I’ve never previously written about directly. August, after all, is the month of Lovecraft’s birth, making it an ideal time to give him his due.

Whether Pulp Fantasy Library continues beyond that will depend largely on reader interest.

As I’ve noted before, these posts are among the most time-consuming I write. They require not only re-reading the stories but also researching their backgrounds, thinking about their content, and then writing something worthwhile about them. That’s time I could otherwise be spending on Thousand Suns, Secrets of sha-Arthan, or any number of other creative endeavors.

To be clear, I’m not complaining: I wouldn’t even consider bringing the series back if I didn’t think it had value. However, I do want to make sure that value is shared by readers. If this is something you’d like to see more of, I’d appreciate hearing from you, whether through blog comments, emails, or other means. Grognardia has always thrived on the feedback and enthusiasm of its readers and your encouragement helps me decide where to focus my limited time and energy.

I’ve been feeling more creatively energized lately than I have in many years, perhaps even since the earliest days of the blog. Between that and the addition of my Substack, I have more outlets for my writing than ever, but also more decisions to make about what gets my attention. If Pulp Fantasy Library is something you'd like to see more of, this is the time to say so.

In the meantime, I hope you’ll enjoy this August’s quartet of Lovecraft posts. I’m looking forward to writing them.July 6, 2025

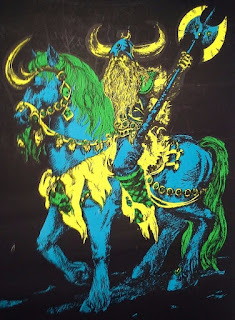

Dungeons & Dreamscapes

I’ve often said I feel fortunate to have discovered Dungeons & Dragons when I did, before the dead hand of brandification settled over the game and drained it of the wild, untamed esthetic that once made it so visually compelling and culturally strange. In the years before D&D became a polished entertainment “property,” its visual identity was a chaotic collage of influences drawn from unexpected sources: psychedelic counterculture, turn-of-the-century Art Nouveau, underground comix, pulp magazines, and outsider art. Monsters leered with extra eyes and boneless limbs, while dungeons sprawled like fever dreams. There was a visual lawlessness to early D&D (and to roleplaying games more broadly) that mirrored the creative freedom of its rules. That freedom invited players to imagine fantasy worlds that were not simply adventurous, but also surreal, grotesque, and deeply personal.

These thoughts came back to me recently while flipping through some of the Dungeons & Dragons materials I encountered shortly after I took my first tentative steps into the hobby. Looking at them now, decades later, I’m struck not just by their content, but also by their form. Much of the art did not resemble anything I had seen before. It was crude at times, even amateurish by the standards of commercial illustration. Yet, it was also evocative in a way that transcended technique. These images did not so much depict a fantasy world as suggest one, obliquely, symbolically, even irrationally. Many felt like fragments from dreams or relics from some lost visionary tradition and, on some level, they were.

These thoughts came back to me recently while flipping through some of the Dungeons & Dragons materials I encountered shortly after I took my first tentative steps into the hobby. Looking at them now, decades later, I’m struck not just by their content, but also by their form. Much of the art did not resemble anything I had seen before. It was crude at times, even amateurish by the standards of commercial illustration. Yet, it was also evocative in a way that transcended technique. These images did not so much depict a fantasy world as suggest one, obliquely, symbolically, even irrationally. Many felt like fragments from dreams or relics from some lost visionary tradition and, on some level, they were.That tradition was a subterranean one, largely outside the orbit of mainstream fantasy art. Psychedelic poster designers, Symbolist painters, and zinesters working on the margins of the counterculture all contributed, consciously or not, to the strange visual DNA of early roleplaying games. Before branding demanded consistency and legibility, Dungeons & Dragons was porous enough to absorb all of it. The result was an esthetic that was both wildly eclectic and, paradoxically, cohesive in its weirdness. It didn’t feel like a mainstream product; it felt like artifacts from another world.

Today, it’s common to point to Tolkien as the primary visual and thematic influence on early D&D. His mark is real and unmistakable (despite what Gary Gygax wanted us to believe). However, when you examine the actual artwork that filled TSR’s products in the late 1970s and early ’80s – the era when I entered the hobby – you find yourself far from Middle-earth. Instead of noble elves and stoic rangers, you instead see grotesque creatures, warped anatomy, anatomical impossibilities, and alien geometries rendered in flat inks and, later, garish colors. This wasn’t the Shire. This was something older, more primal, and far stranger.

Where did this esthetic come from?

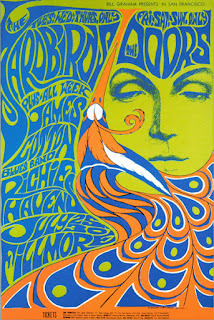

As I’ve already suggested, part of the answer lies in the psychedelic explosion of the 1960s. This was a cultural moment that sought to dissolve the boundaries between consciousness and art. Psychedelic artists like Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso developed a visual language rooted in abstraction, distortion, and saturated color, a kind of sensory mysticism meant to evoke altered states. Concert posters and album covers became portals to other dimensions. Meanwhile, underground comix, like those of Robert Crumb or Vaughn Bodē, combined sex, satire, fantasy, and absurdism into worlds that gleefully rejected the conventions of good taste or coherent storytelling.

As I’ve already suggested, part of the answer lies in the psychedelic explosion of the 1960s. This was a cultural moment that sought to dissolve the boundaries between consciousness and art. Psychedelic artists like Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso developed a visual language rooted in abstraction, distortion, and saturated color, a kind of sensory mysticism meant to evoke altered states. Concert posters and album covers became portals to other dimensions. Meanwhile, underground comix, like those of Robert Crumb or Vaughn Bodē, combined sex, satire, fantasy, and absurdism into worlds that gleefully rejected the conventions of good taste or coherent storytelling.While Gygax and Arneson were not themselves products of this milieu, the audience they attracted often was – college students, sci-fi fans, and other oddballs shaped by the psychedelic visual environment of the late ’60s and early ’70s. I was younger than that cohort, a child in fact, not a teen or adult, but even I absorbed some of its esthetic currents. They filtered into my world through album covers, comics, cartoons, toys, and the hazy, low-fi look of the decade itself. I didn’t yet know what most of these things meant, but I nevertheless felt their strangeness. They stuck with me, shaping my imagination in ways I only later came to understand.

TSR, for its part, didn’t initially reflect these influences. Much of the earliest D&D art was traditional or utilitarian, inherited from the wargaming scene. As the game’s popularity exploded in 1979, TSR began to draw on a new crop of young illustrators, many of them influenced, directly or indirectly, by underground comix, countercultural poster art, and the lingering weirdness of the 1970s. Their work didn’t smooth out the chaos from which early D&D was born – it amplified it.

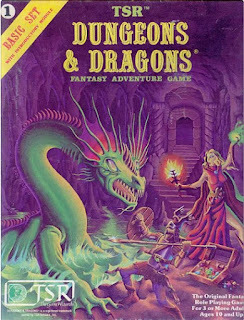

No one embodied this more than Erol Otus. His illustrations for the Basic and Expert boxed sets are among the most iconic in the history of the hobby, as well as some of the strangest. Otus’s monsters don’t just look dangerous; they look wrong, like something glimpsed in a fever or half-remembered from a dream. His color palettes are lurid, his anatomy grotesquely playful, his compositions uncanny and theatrical. His esthetic doesn’t belong to heroic fantasy. It belongs to a blacklight poster, hung next to a velvet mushroom print and a battered copy of The Teachings of Don Juan.

No one embodied this more than Erol Otus. His illustrations for the Basic and Expert boxed sets are among the most iconic in the history of the hobby, as well as some of the strangest. Otus’s monsters don’t just look dangerous; they look wrong, like something glimpsed in a fever or half-remembered from a dream. His color palettes are lurid, his anatomy grotesquely playful, his compositions uncanny and theatrical. His esthetic doesn’t belong to heroic fantasy. It belongs to a blacklight poster, hung next to a velvet mushroom print and a battered copy of The Teachings of Don Juan.Otus, whether intentionally or not, brought the visual grammar of psychedelia into the core of D&D. In doing so, he captured something essential about the game: that it wasn’t just a fantastic medieval wargame; it was a tool for exploring the irrational, the liminal, the transformed. Other artists took up different parts of this same sensibility. Dave Trampier’s work, for example, especially his iconic AD&D Players Handbook cover, radiates a stillness and mystery more akin to myth or ritual than heroic adventure. Other similarly restrained pieces of early D&D likewise seem caught between worlds.

The same spirit is evident in third-party publications. Judges Guild modules are packed with crude, surreal illustrations that throb with symbolic weirdness. David Hargrave’s Arduin Grimoire goes even further. It's a deranged collage of cybernetic demons, magical diagrams, flying sharks, and bizarre maps that reads like D&D filtered through Zardoz. It’s no coincidence that Hargrave gave Otus his first professional credit. They were kindred spirits, working not within a genre, but along the outermost fringes of it.

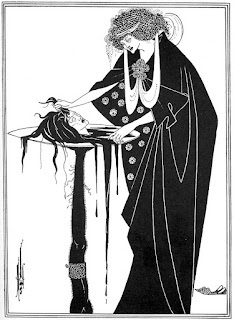

Beyond psychedelia, another artistic thread ran through the background: the ornate, esoteric elegance of Art Nouveau. The flowing lines of Aubrey Beardsley, the sacred geometry of Alphonse Mucha, and the decadent mysticism of Gustav Klimt all haunt the margins of early RPG art. Beardsley’s illustrations for Salome or Le Morte d’Arthur look, at times, like direct ancestors to early D&D's depictions of witches, sorcerers, and demons. These fin de siècle influences were rediscovered during the 1960s counterculture and found their way, through posters, tarot decks, and zines, into the strange visual stew of early roleplaying games.

Beyond psychedelia, another artistic thread ran through the background: the ornate, esoteric elegance of Art Nouveau. The flowing lines of Aubrey Beardsley, the sacred geometry of Alphonse Mucha, and the decadent mysticism of Gustav Klimt all haunt the margins of early RPG art. Beardsley’s illustrations for Salome or Le Morte d’Arthur look, at times, like direct ancestors to early D&D's depictions of witches, sorcerers, and demons. These fin de siècle influences were rediscovered during the 1960s counterculture and found their way, through posters, tarot decks, and zines, into the strange visual stew of early roleplaying games.Even the dungeon itself is shaped by this visionary impulse. Early dungeons aren’t realistic structures. They’re mythic underworlds. They don’t obey architectural logic but symbolic logic, filled with teleporters, talking statues, secret doors, and fountains of infinite snakes. They’re not places so much as thresholds. To descend into a dungeon is to cross into a space where transformation of one kind or another is not only possible but expected.

That’s why so many early modules have such power decades later. Quasqueton, Castle Amber, White Plume Mountain, The Ghost Tower of Inverness – they’re not just combat arenas. They’re almost spiritual landscapes, mythic spaces presented as keyed maps. The artwork used to depict them conjures a mood, a worldview, a sense of mystery, inviting players to see fantasy not as genre convention, but almost as a moment of altered perception.

However, as D&D became a brand, this strangeness was steadily scrubbed away. Style guides were introduced. Idiosyncratic artists gave way to professionals. The game’s visuals became cleaner, more representational, more standardized. With that polish came a flattening of the imagination. D&D no longer looked like a vision; it looked like product.

However, as D&D became a brand, this strangeness was steadily scrubbed away. Style guides were introduced. Idiosyncratic artists gave way to professionals. The game’s visuals became cleaner, more representational, more standardized. With that polish came a flattening of the imagination. D&D no longer looked like a vision; it looked like product.This, I think, is what so many of us in the early days of the Old School Renaissance were reaching for, even if we couldn’t name it at the time. We were looking for the weirdness again, for the ecstatic, chaotic, sometimes unsettling energy that marked those early years. We remembered when fantasy didn’t have to be safe or heroic or respectable. We remembered when D&D looked like a door to Somewhere Else.

That's because fantasy, properly understood, is not an esthetic. It is a vision of the world tilted just enough to let the impossible shine through. Like the pioneers of science fiction and fantasy, the early artists of Dungeons & Dragons understood this. Otus understood it. Trampier understood it. So did Beardsley, Griffin, and countless anonymous illustrators working on mimeographed zines and early rulebooks in the 1970s. They weren’t just drawing monsters or dungeons. They weren’t just illustrating rules. They were revealing other worlds.July 4, 2025

Epistle

July 3, 2025

CleriCon 2025

While I'm looking forward to attending Gamehole Con in mid-October, I have often bemoaned the fact that there aren't more RPG conventions I'd like to attend closer to home. That's why I was very pleased to discover the existence of CleriCon, now in its third year. Organized by The Dungeon Minister – a real-life cleric – it's a small but growing old school-focused convention in Glen Williams, Ontario (about an hour outside Toronto).

While I'm looking forward to attending Gamehole Con in mid-October, I have often bemoaned the fact that there aren't more RPG conventions I'd like to attend closer to home. That's why I was very pleased to discover the existence of CleriCon, now in its third year. Organized by The Dungeon Minister – a real-life cleric – it's a small but growing old school-focused convention in Glen Williams, Ontario (about an hour outside Toronto). I'll be running a Dolmenwood adventure at the con on Saturday, October 25. If any Grognardia readers should find their way to CleriCon, please drop by to say hello. That's probably my favorite thing about gaming conventions: the opportunity to meet my fellow roleplayers in the flesh rather than just online.

Interrogation Transcript

INTERROGATION TRANSCRIPT

SUBJECT: Dennis Lagrange

AFFILIATION: Suspected New America insurgent

LOCATION: Fort Lee Temporary Holding Facility

DATE: 8 December 2000

TIME: 1934 EST

INTERROGATOR: Lt. D. McAllister

TRANSCRIPTION OFFICER: PFC R. Valdez

CLASSIFICATION: SECRET

BEGIN TRANSCRIPT

LAGRANGE:

So that’s it, huh? You finally figured it out. Congratulations. Really. You're quicker than most of the grunts in that junta you call USMEA.

But let me ask you something: what are you gonna do about it?

Throw me in prison? Make another report to General Summers? None of it changes the math.

You think you're preserving something here. Order. Civilization. America. But you're guarding a corpse, friend. You're dressing up a dead empire and pretending it can still give commands. That flag you're flying? It's just a rag someone left behind when the bombs fell.

[Subject paces.]

You want to know the genius of it? No matter what you do, no matter what your bosses do, we win.

You try to be humane, feed a few starving mouths? Makes you look weak. Makes people ask why you’re feeding outsiders when your own patrols are running dry.

But maybe you get smart. Maybe you crack down. Shut the gates. Round people up. Shoot a few looters. Then you're the tyrants. The bad guys. You do our work for us.

That's the beauty of it. You're trapped in the old rules. We're writing new ones.

[Subject leans forward.]

You still don’t get it, do you? The war’s over. Not the fighting. Sure, that’ll drag on a while. But the war? That ended the moment your leaders ran out of answers and reached for the launch keys.

What’s left now is the reckoning. And New America ... we’re the future. The people know it. Hell, even you know it. You’re just too scared to admit it.

So go ahead. Lock me up. Kill me if you’ve got the guts.

Doesn’t matter.

We’re already inside the gates.

END TRANSCRIPT

NOTES: Subject displayed no signs of physical distress. Tone throughout was defiant and confident. No direct operational intelligence volunteered. Recommend psychological evaluation and further containment protocols.

APPROVED: MAJ J. Whittaker, USMEA Intelligence Division

DISTRIBUTION: USMEA Command; Fort Lee Intelligence; NCR Threat Assessment Unit

CLASSIFICATION: SECRET

DO NOT DISTRIBUTE OUTSIDE CLEARED CHANNELS

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers