James Maliszewski's Blog, page 16

June 17, 2025

Retrospective: Gamma World (Third Edition)

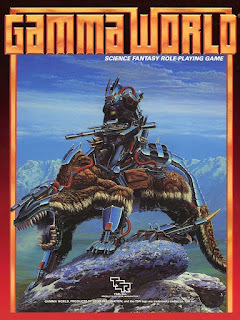

A couple of years ago, I broke with tradition and penned a Retrospective post on the second edition of Gamma World, despite having already written one on the original. I justified the decision by pointing to just how different second edition was, both in tone and presentation, from its predecessor. It stood as a vivid example of how Gamma World – and roleplaying games more broadly – were evolving in the early 1980s. By that same logic, the third edition of Gamma World, released in 1986, surely warrants a post of its own, as the differences it introduced were even more pronounced.

A couple of years ago, I broke with tradition and penned a Retrospective post on the second edition of Gamma World, despite having already written one on the original. I justified the decision by pointing to just how different second edition was, both in tone and presentation, from its predecessor. It stood as a vivid example of how Gamma World – and roleplaying games more broadly – were evolving in the early 1980s. By that same logic, the third edition of Gamma World, released in 1986, surely warrants a post of its own, as the differences it introduced were even more pronounced.Since its debut in 1978, Gamma World has always seemed uncertain whether it wanted to be a madcap romp through a world of radioactive mutants or a more serious science fantasy game exploring its post-apocalyptic setting. That tension runs through every edition, but third edition feels like the first time it was intentional. I remember seeing ads for it in Dragon magazine at the time, and the cover, featuring Keith Parkinson’s vivid illustration, made a strong impression. It hinted at a bold new direction for the game, though I was struck less by its novelty than by its familiarity, having already seen the same image on a TSR calendar the year before.

If the first and second editions of Gamma World were clumsy but endearing offshoots of early D&D design – random, deadly, but bursting with imaginative potential – then the third edition marks a dramatic, and often jarring, departure. Released during a period when TSR was busy retooling many of its games in the wake of Marvel Super Heroes' success, third edition followed the lead of Star Frontiers and embraced the concept of a universal resolution system and its color-coded Action Table (ACT), column shifts, and result factors. While elegant in their original context, the ACT always felt awkward and ill-suited when retrofitted onto existing games. In Gamma World, it comes across less as a refinement and more as a mismatch – neat in theory, but clumsy in practice.

Third edition attempted to marry this new mechanical chassis to the conflicted sensibilities of earlier editions, but, in my view, the result was less than satisfactory. Combat resolution and mutation use now hinged on interpreting results from a chart – an abstraction that sapped much of the immediacy from play. Firing a Mark V Blaster was no longer a simple matter of “roll to hit, roll damage.” Instead, it became a multi-step procedure: find the appropriate ACT column, look at the result, then consult a separate chart to determine the weapon’s actual effect. One might argue this wasn’t dramatically more complex than previous systems, but for those of us who’d long ago internalized the old mechanics, it was anything but intuitive. At best, it felt like change for its own sake; at worst, a solution in search of a problem.

What also stood out – and not in a flattering way – was the presentation. The rulebook was stark and utilitarian in its layout, almost entirely bereft of artwork. What little art it did contain was mostly recycled from earlier editions, along with some lifted from Star Frontiers. A few original illustrations were scattered throughout, but they were the exception rather than the rule. Even the foldout map of Pitz Burke, a centerpiece of second edition, was repurposed here with minimal alteration. Worse still, key rules were split between the main rulebook and a separate “rules supplement” tucked into the box, fragmenting the material and giving the whole package a slapdash feel. It lacked the cohesion one expects from a fully realized edition, and instead felt cobbled together, more like a rushed repackaging than a thoughtfully constructed evolution.

Just as its mechanics felt awkwardly imposed, third edition’s treatment of the Gamma World setting also seemed diminished. Much of the evocative, if sketchy, setting material found in earlier editions was either stripped away or given only the most cursory attention. Take the cryptic alliances, for example: while they’re mentioned, their role in the world feels vague and perfunctory. Gone is the sense, so evident in second edition, that these shadowy factions were vital to understanding the post-apocalyptic landscape. The same could be said for many other aspects of Gamma World’s implied setting. It’s not that these elements are entirely absent, but that their inclusion feels scattershot and half-hearted. There’s a perfunctory, almost apathetic quality to the world-building in third edition, as if the designers were merely checking boxes rather than engaging with the material in a meaningful way. The result is a game that lacks the weird, half-glimpsed coherence that gave earlier editions their charm. It feels like a product made to fill a slot in the release schedule, not one born of creative enthusiasm.

Amidst its uneven mechanics and uninspired presentation, third edition nevertheless hinted at something more ambitious. Scattered throughout the rulebook – and more clearly in the adventure modules that followed – were the outlines of a broader campaign arc, one that seemed intended to link Gamma World to its spiritual progenitor, Metamorphosis Alpha. These modules presented ancient installations, buried technologies, and the tantalizing possibility of uncovering the true origins of the post-apocalyptic world. There were even whispers of the derelict starship Warden, as well as references to other planets and moons of the solar system, suggesting a much larger canvas than previous editions had dared to paint. That, more than anything else, remains the lasting appeal of third edition for me, the first edition to really toy with the fact that Gamma World's apocalypse belongs to the 24th century, not the 20th, and hinted at a setting far more expansive than mutant rabbits and ancient ruins.

Unfortunately, this promising thread was never fully developed. The planned module series was left incomplete and, with the arrival of Gamma World’s fourth edition in 1992, the game was rebooted once more. Any connections to Metamorphosis Alpha were quietly abandoned. Whatever larger vision might have existed was lost, leaving third edition as a curious dead end in the game’s evolution.

In the end, Gamma World Third Edition is a strange, transitional fossil, neither wholly broken nor particularly successful. It represents an attempt to modernize a legacy title by grafting onto it the mechanics of Marvel Super Heroes, but it does so without the conceptual clarity or setting depth needed to make that modernization feel purposeful. What was left is a game that is both overcomplicated and underdeveloped: a patchwork of ideas, some intriguing, others ill-suited, held together by a presentation that feels rushed and indifferent. Yet, for all its flaws, there remains a flicker of something more, an unrealized potential that somehow still has the power to capture my imagination, even if only in fragments.June 16, 2025

REPOST: The Articles of Dragon: Ares

I'm going to cheat for today's installment of this series. Rather than focusing on a single article from issue #84 of Dragon (April 1984), I'm instead going to talk about Ares, the magazine's new science fiction gaming section. First, a bit of background. Between 1980 and 1982, SPI published a gaming magazine entitled

Ares

. The magazine included a complete game in every issue (as was once typical of wargaming magazines), along with articles and reviews. Though not limited to sci-fi by any means, Ares did have a slightly science fictional bent to its content. There were eleven issues of Ares before TSR acquired SPI in 1982, followed by five more issues after the acquisition. The last stand-alone issue of Ares was published in "Winter 1983." TSR never really knew what to do with SPI's properties and wound up frittering them away over the course of the next few years, in the process alienating the company's considerable fanbase, many of whom (quite rightly) felt that TSR had handled the situation very badly. Though TSR tried to make some use of SPI's name and products, only the Ares name survived for long – and even then, "long" is a relative term.

I'm going to cheat for today's installment of this series. Rather than focusing on a single article from issue #84 of Dragon (April 1984), I'm instead going to talk about Ares, the magazine's new science fiction gaming section. First, a bit of background. Between 1980 and 1982, SPI published a gaming magazine entitled

Ares

. The magazine included a complete game in every issue (as was once typical of wargaming magazines), along with articles and reviews. Though not limited to sci-fi by any means, Ares did have a slightly science fictional bent to its content. There were eleven issues of Ares before TSR acquired SPI in 1982, followed by five more issues after the acquisition. The last stand-alone issue of Ares was published in "Winter 1983." TSR never really knew what to do with SPI's properties and wound up frittering them away over the course of the next few years, in the process alienating the company's considerable fanbase, many of whom (quite rightly) felt that TSR had handled the situation very badly. Though TSR tried to make some use of SPI's name and products, only the Ares name survived for long – and even then, "long" is a relative term.From issue #84 to issue #111 (July 1986), Ares was one of my favorite sections of Dragon, since I've always been more of a SF fan than a fantasy one. The section featured articles on games like Traveller and Star Trek and Space Opera , as well as Gamma World , Star Frontiers , and a host of superhero games, especially Marvel Super Heroes . Because sci-fi has always played second (or third) banana to fantasy, you'd have expected that the pool of articles would have been pretty shallow in Ares but that wasn't the case. In my opinion, the quality of the articles in this section was consistently high, higher even than that of the rest of Dragon (which is saying something). However, its appeal was definitely more limited, which is why I suspect it was eventually killed. Why devote some many pages of each issue to genres that are also-rans compared to fantasy, especially D&D's brand of fantasy?

To this day, though, when I look back on the years when I subscribed to Dragon, the Ares articles are among those that stick out most prominently in my mind. Its coverage of Gamma World, for example, was truly excellent and I used a number of its Traveller rules variants over the years. And of course Jeff Grubb's regular "The Marvel-Phile" column was invaluable if you were running a Marvel Super Heroes campaign (or even if you weren't and were just a fan of the comics). I've always thought it a pity that a non-fantasy-centric gaming mag never really gained any degree of prominence. GDW's Challenge, where my first published writings appeared, was a decent stab at such a thing, but it eventually folded, too, much to my disappointment. Like Ares, Challenge filled a hole in the hobby that needed filling. In my opinion, it still does.

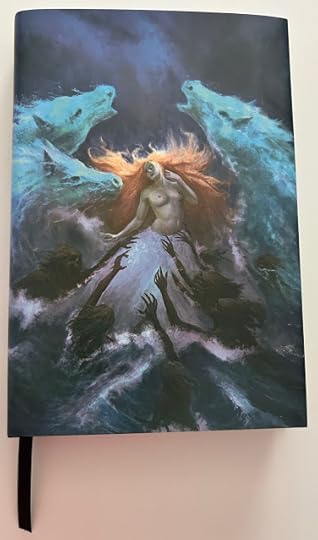

Creep, Shadow! Released

You may remember that, back in 2022, Centipede Press published a new edition of Abraham Merritt's 1932 story, Burn, Witch, Burn! that included an introduction written by yours truly. This year, they followed that up with its sort-of-sequel, Creep, Shadow!, to which I also contributed the introduction. Like its predecessor, it's a beautiful and well-made book, featuring both original dustcover and frontispiece art by Camille Alquier and interior illustrations by the great Virgil Finlay. This new edition is limited to 600 copies, so if you're interested in a copy, you'll probably need to grab one quickly from the Centipede Press website. Burn, Witch, Burn! sold out quickly and, so far as I know, it's never been reprinted.

Here's the dustcover:

This is the credits page:

This is the credits page:

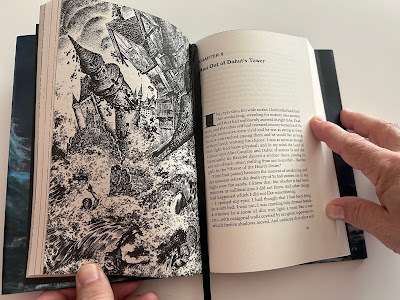

The start of a chapter, showing off a bit of Finlay artwork and the bookmark.

The start of a chapter, showing off a bit of Finlay artwork and the bookmark.

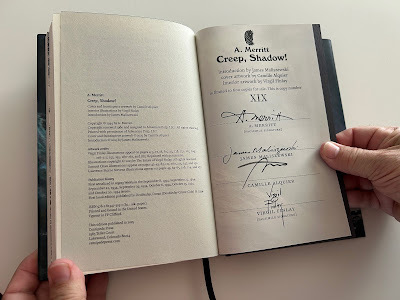

Finally, the signature page at the back of the book. I am dwarf among giants.

Finally, the signature page at the back of the book. I am dwarf among giants.

June 15, 2025

Tourists and Locals

I'm fairly certain I've previously expressed my general dislike for "one-shots" or "mini-campaigns." To be clear, my dislike isn’t absolute, but I rarely seek them out. When I do participate in them, I often come away slightly unsatisfied. One of the greatest joys of roleplaying games, at least for me, lies in the continuity of a long campaign: the way characters grow, change, and accumulate history over time; how a setting deepens and acquires texture; how throwaway details from early sessions suddenly take on new meaning months (or even years) later. If given the chance, I prefer to settle in, to put down roots, and see what emerges over the long haul. That’s usually my goal when I sit down at the table with friends. I want a campaign, not a fling.

And yet ...

Over the past few years, I've come to appreciate the distinct pleasures of convention games: those four-hour sessions with a group of strangers that begin and end in a single afternoon or evening. I had a great time at last year's Gamehole Con and came away from several sessions feeling energized and inspired. That’s part of the reason I’m looking forward to signing up for more this year. On paper, con games are the antithesis of what I usually look for in roleplaying. They’re self-contained, focused, and impermanent. Once the session is over, it’s over. So why don’t they leave me with the same hollow feeling that a short-lived home campaign often does?

While I’m not above hypocrisy, I think I have a good sense of why I enjoy con games more than I would have expected.

Playing a game at a convention is, for me, a form of tourism. I show up, meet new people, and explore a small slice of a game or setting with which I may not be familiar. It’s a snapshot. There’s no illusion of permanence, no lingering sense of “what might have been.” The characters might be memorable and the play enjoyable, but everyone understands from the outset that this is a limited-time engagement. It’s a visit, not a move.

A home campaign with friends, by contrast, is more like choosing to live somewhere. There’s an implicit commitment. We’re investing in something meant to last. That shared commitment changes everything. When I play with friends, I generally don’t want the game to have an expiration date. I want room to build, to wander, to return to familiar locations, to interact with recurring NPCs, to watch the slow accretion of detail and consequence. A one-off in that context feels like a house without a foundation –furnished, perhaps, for a party, but not built for living in.

There’s also a difference in ambition. A convention game rarely tries to be more than it is. It knows its limits and, when well-run, delivers something satisfying within them. A one-shot at home, on the other hand, often aspires to be a mini-campaign or the seed of something larger, but without the time to grow into either. The result is frequently a sense of missed potential. The game ends just as things are getting interesting. I experienced this recently during a game of Dragonbane that one of my Dolmenwood players refereed for us. It was fun but also a little bit frustrating: a glimpse of something promising that ended too soon.

None of this is meant as a criticism of short-form RPG play. Many people love one-shots and mini-campaigns and probably with good reason. For me, though, the pleasure of roleplaying originates elsewhere. I want to stay, not merely pass through. I want to know the locals, not just see the sights.

But every now and then, it’s good to be a tourist.June 14, 2025

Rich and Creamy

A couple of weeks ago, I mentioned that, after so many years of refereeing Empire of the Petal Throne, I found myself craving a vanilla fantasy setting – something simpler and more straightforward than Tékumel but that was nevertheless very well done. I received a lot of good suggestions in the comments to that post, but one of the best ones came directly from Rob Conley, a fellow blogger who's done some truly excellent work over the years, especially regarding the subject of sandbox settings, both for fantasy and for Traveller. If you're at all interested in sandboxes, I highly recommend you check out those series of posts. In my opinion, they're pretty close to definitive.Rob has done a lot of other great stuff worthy of your attention, like Blackmarsh, a free hexcrawl setting in the tradition of the Outdoor Survival map OD&D suggested the referee use for adjudicating wilderness travel and exploration. Blackmarsh is one of my favorite things from the first few years of the Old School Renaissance. I made use of it in my Dwimmermount campaign to represent the region immediately to the north of the main campaign area. It's a great example of well-done vanilla fantasy, providing a referee with just enough material to spark his own imagination without limiting his options.

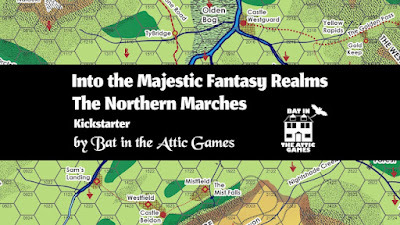

A couple of weeks ago, I mentioned that, after so many years of refereeing Empire of the Petal Throne, I found myself craving a vanilla fantasy setting – something simpler and more straightforward than Tékumel but that was nevertheless very well done. I received a lot of good suggestions in the comments to that post, but one of the best ones came directly from Rob Conley, a fellow blogger who's done some truly excellent work over the years, especially regarding the subject of sandbox settings, both for fantasy and for Traveller. If you're at all interested in sandboxes, I highly recommend you check out those series of posts. In my opinion, they're pretty close to definitive.Rob has done a lot of other great stuff worthy of your attention, like Blackmarsh, a free hexcrawl setting in the tradition of the Outdoor Survival map OD&D suggested the referee use for adjudicating wilderness travel and exploration. Blackmarsh is one of my favorite things from the first few years of the Old School Renaissance. I made use of it in my Dwimmermount campaign to represent the region immediately to the north of the main campaign area. It's a great example of well-done vanilla fantasy, providing a referee with just enough material to spark his own imagination without limiting his options.Now, Rob is preparing to release another sandbox, one built on the foundation of Blackmarsh and related projects: Into the Majestic Fantasy Realms: The Northern Marches. As its title suggests, The Northern Marches is connected to Rob's Majestic Fantasy RPG , but is completely usable with your preferred old school fantasy rules. In that respect, it's a lot like Judges Guild's old Wilderlands of High Fantasy material in that it sketches out a huge amount of real estate that can be adopted and adapted as the referee sees fit. Rob has a long history with the Wilderlands setting, so I doubt he'd argue against saying his Majestic Fantasy Realms setting has been inspired by it, even if it's very much its own unique thing.

Rob very kindly shared with me his latest draft of The Northern Marches, which is an immense document of over 100,000 words. Don't be put off by its length. Though there are some high-level discussions of history, geography, politics, and religion, the vast majority of this text is devoted to short but evocative descriptions of the notable hexes of the four regional maps included with the book. Just as useful is the section devoted to traveling within the setting and all that that entails – caravans, ships, exhaustion, rates of travel, and more. This is, after all, a sandbox setting, so these sorts of things are absolutely essential to make full use of it.

You can see the full table of contents, along with a preview of the setting here. Another overview of the setting and this project can be found in this post on Rob's blog. It's really well done and very much in keeping not just with the excellent material Rob has made before, but also with his work on creating and running sandbox campaigns. I was very impressed by the scope of The Northern Marches, not to mention the obvious work Rob has put into making it accessible and usable. While it's still too early to say how I might eventually decide to sate my craving for vanilla fantasy, I can say there's a very good chance I'll make use of The Northern Marches in one way or another. If that sounds like something you might be interested in, I highly recommend checking it out.

June 13, 2025

Things That Go Bump in the Decade

This being the only Friday the 13th of 2025, I couldn't pass up the opportunity to muse a little about the spooky stuff I grew up with during my childhood in the 1970s, things that no doubt informed my continued fascination with the uncanny even today.

Back then, the world still seemed full of mysteries – or at least it was easy to imagine that it was. Stories of haunted houses, UFOs, Bigfoot, the Loch Ness Monster, and all manner of cryptids and bizarre phenomena were staples of popular culture. They filled the pages of supermarket tabloids, popped up in solemnly narrated TV specials, and circulated in schoolyard whispers. Even if few people truly believed in them, almost everyone enjoyed talking about them. The possibility alone was enough.

Looking back, it’s striking how pervasive the weird was in everyday life. I vividly recall garish paperbacks detailing “true” encounters with the unknown, cartoons and comics riffing on paranormal themes, and, of course, the ever-present influence of movies and television shows like In Search Of..., Project U.F.O., Kolchak: The Night Stalker, and The Amityville Horror, among many, many more. These stories occupied a curious space in the cultural imagination – not quite believed, not quite disbelieved either, and all the more compelling for it. They invited speculation, encouraged imagination, and cultivated a sense of wonder tinged with dread.

Even as a kid, I never bought into most of it. I didn’t spend my nights scanning the skies for flying saucers or lurking in the woods hoping to glimpse Sasquatch. But I wanted to believe, at least a little. The world felt more interesting, more alive, with those possibilities lurking just beyond the edges of certainty. What if there was something out there? That question alone was enough to fire my imagination.

And fire it did. By the time I discovered Dungeons & Dragons and, through it, other roleplaying games, I was already primed for them. After all, I’d spent years immersed in tales of mysterious creatures, unexplained lights, and restless spirits. RPGs gave me a new framework to explore those ideas, one where I wasn’t just reading or hearing the stories but helping to create them. I could conjure new monsters, new haunted places, new eerie events, and imagine how I or others might respond if the strange and uncanny ever crossed into our reality.

Today, that world of half-believed wonder seems distant, if not entirely gone. The Internet, with its unblinking capacity to record, debunk, and explain, has driven much of the weird to the cultural margins. Cell phone cameras are everywhere and the lack of blurry, ambiguous evidence speaks louder than all the old rumors ever did. Of course, being middle-aged hasn’t helped my credulity either. I’m more skeptical now, more prone to roll my eyes than widen them, but I still feel a twinge of wistfulness. There was a magic in those stories – the giddy unease, the delighted fear, the sense that the world might be stranger than it appeared and that something astonishing might be hiding in plain sight.

I don’t miss the bad haircuts or the shag carpeting, but I do miss that feeling, that delicious tension between belief and disbelief, the sense of possibility that once seemed to shimmer in the air. Maybe that’s why, even after more than forty years, I’m still rolling dice and spinning yarns of my own. I’m chasing that feeling, the thrill of stepping into the unknown, of turning the corner and finding that the world is bigger, weirder, and more mysterious than we’d dared to imagine.

On a superstitious day like today, I try to remember what it felt like to believe – not entirely, but just enough to wonder.June 12, 2025

Traveller Distinctives: World Generation

When GDW released Traveller in 1977, it stood apart from other roleplaying games of the time in several important ways. Most notably, it was not a fantasy game. It didn’t rely on the tropes of sword and sorcery or draw inspiration from the likes of Robert E. Howard or J.R.R. Tolkien. Instead, Traveller presented a vast, impersonal universe of interstellar trade, mercenary tickets, and political intrigue. Perhaps even more significant than its subject matter, however, was its approach to setting creation. Traveller’s world generation system, unlike the improvisational or campaign-specific methods typical of Dungeons & Dragons, was systematic, abstract, and procedurally expansive, offering something genuinely new in RPG design.

When GDW released Traveller in 1977, it stood apart from other roleplaying games of the time in several important ways. Most notably, it was not a fantasy game. It didn’t rely on the tropes of sword and sorcery or draw inspiration from the likes of Robert E. Howard or J.R.R. Tolkien. Instead, Traveller presented a vast, impersonal universe of interstellar trade, mercenary tickets, and political intrigue. Perhaps even more significant than its subject matter, however, was its approach to setting creation. Traveller’s world generation system, unlike the improvisational or campaign-specific methods typical of Dungeons & Dragons, was systematic, abstract, and procedurally expansive, offering something genuinely new in RPG design.At a time when most referees were painstakingly handcrafting maps, cities, and dungeons for their games, Traveller provided a straightforward but elegant toolset for generating entire subsectors of space, one hex at a time. As outlined in Book 3 of the original boxed set, aptly titled Worlds and Adventures, each world was reduced to a Universal World Profile (UWP), a concise string of alphanumeric codes representing atmosphere, population, government type, law level, and more. Though cryptic at first glance, these codes become, in practice, powerful spurs to creativity, prompting referees to extrapolate complex social and environmental conditions from simple numeric entries.

Even before the first session began, Traveller encouraged the referee to engage in a kind of solitary, exploratory “play.” Generating worlds, assigning trade classifications, and mapping out political and economic relationships quickly becomes an absorbing exercise in its own right, as any long-time Traveller referee can attest. Indeed, it's a major part of the game's fun. Rather than merely preparing background details, the referee is, in effect, discovering the setting as he rolls the dice. The process became a kind of solo game, one where the rules and randomness combined to yield an emergent and unpredictable sector of space – varied, dynamic, and rich with potential for adventure.

The UWP itself is a marvel of minimalist design. Each digit or letter conveys essential information about a world, but does so in a way that suggests deeper histories, social structures, and gameplay consequences. A high-tech world with a low law level and a major starport hints at a bustling, semi-legal trade hub teeming with intrigue. A planet with a corrosive atmosphere and feudal government might suggest dying aristocracies clinging to power amidst environmental collapse. The referee is handed the bare bones of a world, but the system demands logical extrapolation for understanding, making worldbuilding a disciplined act of imaginative interpretation.

In contrast to the tendency of Dungeons & Dragons toward medieval pastiche, Traveller offers fewer cultural defaults. The worlds it generates are often strange, uneven, and wildly diverse in terms of tech level, population, and governance, even when separated by only a single parsec. This patchwork character isn’t a flaw. Instead, it suggests a galaxy shaped by ancient collapses, forgotten wars, and the long, staggered climb of civilization across the stars. The system invites referees to consider not just planetary conditions, but also their histories and interrelations.

Crucially, Traveller’s world generation is not mere flavor text. It directly informs core gameplay systems: trade tables, starship design, navigation, and random encounters all hinge, to varying degrees, on the specifics of a world’s UWP. A character’s ability to turn a profit, refuel a ship, or avoid entanglement with the authorities likewise depends on the values generated for each planet. The setting is not simply a backdrop, but a source of friction and consequence. Logistics and environment shape player choices in a more concrete and procedural way than in early Dungeons & Dragons (or arguably in any version of it).

This interdependence gives real weight to the act of, well, traveling from world to world across a subsector hex map. Jumping into a new system is never a formality; it’s a calculated risk. Will there be fuel available? Is the local government welcoming or hostile? Can the party offload its cargo for a profit or will they be detained and searched upon landing? The interconnected nature of the world generation tables feeds into a broader gameplay loop, rewarding both strategic planning and seat-of-your-pants improvisation.

Where early D&D encouraged a bottom-up style of worldbuilding – start with a dungeon, add a nearby village, and let the world expand outward through play – Traveller supports and even rewards a top-down approach. A referee could generate an entire subsector before the players had even rolled up their characters. This inversion suggests a different philosophy of play, one less concerned with "zero to hero" advancement and more focused on navigation (literal and figurative) through a complex and often indifferent universe.

It’s also worth emphasizing that the original 1977 edition of Traveller came with no predefined setting. The now-iconic Third Imperium, with which the game would later become closely associated, didn’t appear until 1979’s The Spinward Marches. Initially, the game offered only methods and tools for generating one’s own interstellar polities, trade routes, and points of conflict. That openness was deliberate. It invited referees to craft their own empires, borderlands, pirate nests, and forgotten colonies. Because of the inherent randomness in the system, even the referee could be surprised by what emerged, lending the process an exploratory thrill that echoed the game’s broader focus.

This is why I consider Traveller’s world generation system not only one of its most distinctive features, but a landmark in early RPG design. With nothing more than a few tables and a handful of dice, a referee could conjure up entire regions of space that are structured, coherent, and teeming with possibility. More than that, the system reflects and reinforces the thematic core of the game itself: a universe not of dungeons and dragons, but of distance, data, and discovery. Nearly fifty years later, it remains unmatched for its combination of utility and elegance.June 11, 2025

The Hidden Masters of Pulp Fantasy

One of the regular series for which this blog was once known is Pulp Fantasy Library, in which I highlighted individual fantasy and science fiction stories I felt had been influential, directly or indirectly, on the development of the hobby of roleplaying. The series eventually grew to more than three hundred entries and taught me a great deal in the process of writing it. However, it also required considerable effort and often received little reader engagement, so I brought it to a quiet close in 2023. I sometimes consider reviving it in a modified form, but I’ve yet to find the right approach. Still, I keep thinking about these early works of fantasy, which is what led to this post.

One of the regular series for which this blog was once known is Pulp Fantasy Library, in which I highlighted individual fantasy and science fiction stories I felt had been influential, directly or indirectly, on the development of the hobby of roleplaying. The series eventually grew to more than three hundred entries and taught me a great deal in the process of writing it. However, it also required considerable effort and often received little reader engagement, so I brought it to a quiet close in 2023. I sometimes consider reviving it in a modified form, but I’ve yet to find the right approach. Still, I keep thinking about these early works of fantasy, which is what led to this post.From the vantage point of the first quarter (!) of the twenty-first century, it’s all too easy to forget just how strange fantasy and science fiction once were – not merely in their imaginative content but in the intellectual and spiritual traditions from which they drew. We tend to think of early speculative fiction as arising primarily from a matrix of adventure tales, scientific romances, and classical mythology. However, another powerful and often overlooked influence is the world of Spiritualism, Theosophy, and other esoteric traditions. These weren’t mere fads in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; they were serious systems of belief for many, including a surprising number of the authors who helped lay the foundations of what we now call genre fiction.

Even more fascinating is how many once-occult concepts have since become commonplaces of fantasy and science fiction, like astral projection, past lives, lost advanced civilizations, invisible planes of existence, and cosmic cycles of spiritual evolution, to name just a few obvious ones. These weren’t originally the products of scientific or rationalist speculation. They were occult doctrines, often articulated with the structure and certainty of any other religion. Early speculative fiction served as a powerful conduit for these ideas, transmitting them into the cultural imagination.

Take, for instance, astral projection, which recurs throughout pulp fantasy and science fiction. In Theosophy, this is the “etheric body” or “etheric double” leaving the physical body to traverse the astral plane. In fiction, this idea becomes John Carter’s unexplained voyage to Barsoom in

A Princess of Mars

, where his body remains behind on Earth while his spirit is transported to another world by sheer force of will. Burroughs never offers a scientific explanation for the phenomenon nor did he need to do so. His readers would likely have recognized the trope from already extant popular occult literature.

Take, for instance, astral projection, which recurs throughout pulp fantasy and science fiction. In Theosophy, this is the “etheric body” or “etheric double” leaving the physical body to traverse the astral plane. In fiction, this idea becomes John Carter’s unexplained voyage to Barsoom in

A Princess of Mars

, where his body remains behind on Earth while his spirit is transported to another world by sheer force of will. Burroughs never offers a scientific explanation for the phenomenon nor did he need to do so. His readers would likely have recognized the trope from already extant popular occult literature.Similarly, reincarnation and karma, central tenets of Theosophy and many forms of Eastern-influenced Spiritualism, appear in the works of authors like Talbot Mundy, whose protagonists sometimes recall past lives in ancient empires. The same is true of many tales penned by Abraham Merritt. In The Star Rover, Jack London tells the story of a prisoner who escapes his unjust physical confinement by entering trance states that allow him to access a series of former incarnations. This isn’t merely a fictional conceit; it reflects a specific metaphysical worldview in which human identity unfolds across many lifetimes, a view that gained traction during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Even readers who didn’t share this worldview would nevertheless have been familiar with it.

William Hope Hodgson is another fascinating case. He blends arcane science with mystical speculation in his "Carnacki the Ghost-Finder" stories, which feature protective sigils, vibrational zones, and references to the "Outer Circle," a realm inhabited by malevolent entities existing just beyond human perception. All of these ideas draw heavily on contemporary occultism. His novel The Night Land, a work of science fantasy more than horror, is set on a dying Earth haunted by monstrous spiritual forces and saturated with the oppressive weight of cosmic time. It echoes Theosophical doctrines of vast evolutionary cycles and the occult preoccupation with psychic resistance to spiritual evil.

William Hope Hodgson is another fascinating case. He blends arcane science with mystical speculation in his "Carnacki the Ghost-Finder" stories, which feature protective sigils, vibrational zones, and references to the "Outer Circle," a realm inhabited by malevolent entities existing just beyond human perception. All of these ideas draw heavily on contemporary occultism. His novel The Night Land, a work of science fantasy more than horror, is set on a dying Earth haunted by monstrous spiritual forces and saturated with the oppressive weight of cosmic time. It echoes Theosophical doctrines of vast evolutionary cycles and the occult preoccupation with psychic resistance to spiritual evil.Marie Corelli (born Mary Mackay), once one of the most popular authors in the English-speaking world, is now rarely read. Her novel, A Romance of Two Worlds, for example, blends Spiritualist belief with melodrama and science fictional concepts, such as portraying electricity as a bridge between the material and spiritual realms. She directly influenced writers like H. Rider Haggard and even Arthur Machen, both of whom in turn shaped the subsequent development of fantasy. Even Edward Bulwer-Lytton, now best known for the infamous incipit “It was a dark and stormy night,” was a serious student of esoteric lore. His novel Zanoni depicts an immortal Chaldean adept who achieves transcendence through secret knowledge, an early example of the “hidden masters” who would later become a staple of Theosophy.

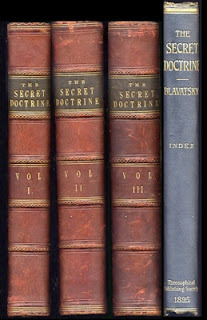

Which, of course, brings us to Theosophy itself, which had perhaps the most lasting and far-reaching impact on the development of both esoteric thought and fantasy. Founded in the 1870s by the Russian-born mystic, Helena Blavatsky, Theosophy combined elements of Hinduism, Buddhism, Neoplatonism, and esoteric Christianity into a vast occult cosmology. Through books, journals, and lectures, it promoted a view of the universe in which mankind was but one phase in an immense spiritual drama, involving lost continents, ascended masters, and ancient wisdom. These ideas found fertile ground in genre fiction. The controversial “Shaver Mystery” stories published in Amazing Stories in the mid to late 1940s and purportedly based on true events involve ancient subterranean races like the evil Deros (which itself served as an inspiration to Gary Gygax). Shaver's stories read like Theosophy blended with pulp sensationalism.

Which, of course, brings us to Theosophy itself, which had perhaps the most lasting and far-reaching impact on the development of both esoteric thought and fantasy. Founded in the 1870s by the Russian-born mystic, Helena Blavatsky, Theosophy combined elements of Hinduism, Buddhism, Neoplatonism, and esoteric Christianity into a vast occult cosmology. Through books, journals, and lectures, it promoted a view of the universe in which mankind was but one phase in an immense spiritual drama, involving lost continents, ascended masters, and ancient wisdom. These ideas found fertile ground in genre fiction. The controversial “Shaver Mystery” stories published in Amazing Stories in the mid to late 1940s and purportedly based on true events involve ancient subterranean races like the evil Deros (which itself served as an inspiration to Gary Gygax). Shaver's stories read like Theosophy blended with pulp sensationalism.Even Clark Ashton Smith, whom regular readers will know is my favorite of the Weird Tales trio, drew on esoteric themes. Ideas like cyclical time, forgotten civilizations, and arcane knowledge recur throughout his work. His Zothique cycle, set on the last continent of a dying Earth, reflects the Theosophical notion of a future “seventh root race” and the eventual exhaustion of history.

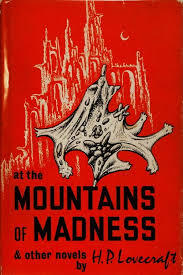

Against this background, H.P. Lovecraft stands out, not because he rejected religion in general (though he did), but because he specifically targeted Spiritualism and occultism. He was deeply familiar with the claims of mediums, astrologers, and Theosophists and dismissed them with open contempt. In his correspondence, he regularly mocks the “credulous” who place faith in séances, reincarnation, and similar beliefs. At the behest of Harry Houdini, Lovecraft even collaborated on a book titled The Cancer of Superstition, intended as a wholesale debunking of Spiritualist claims. The book was never completed due to Houdini’s sudden death in 1926.

Against this background, H.P. Lovecraft stands out, not because he rejected religion in general (though he did), but because he specifically targeted Spiritualism and occultism. He was deeply familiar with the claims of mediums, astrologers, and Theosophists and dismissed them with open contempt. In his correspondence, he regularly mocks the “credulous” who place faith in séances, reincarnation, and similar beliefs. At the behest of Harry Houdini, Lovecraft even collaborated on a book titled The Cancer of Superstition, intended as a wholesale debunking of Spiritualist claims. The book was never completed due to Houdini’s sudden death in 1926.Despite this, Lovecraft’s stories are filled with forbidden books, lost knowledge, and ancient alien races whose truths are too terrible for the human mind to bear. In this way, Lovecraft doesn’t discard the tropes of occult literature – he inverts them. Where Theosophy promised spiritual enlightenment and cosmic unity, Lovecraft offers only madness, degeneration, and a universe that is not merely indifferent but actively hostile to notions of human significance. His “gods” are not hidden masters but incomprehensible and uncaring forces. Structurally, however, he preserves much of the occult worldview: a hidden reality lurks behind the surface of things, accessible only to initiates – scholars, madmen, and cultists. Lovecraft didn’t reject that structure; he twisted it and filled it with dread.

All of this makes it remarkable just how thoroughly modern fantasy and science fiction still bear the imprint of these early occult influences. Astral travel, alternate planes, soul transference, hidden masters, and cosmic cycles remain staples of the genres. They’re treated today as neutral, even secular, tropes of worldbuilding, even though their origins are anything but secular. They are spiritual, mystical, and often explicitly religious in intent.

My purpose in this post isn't to diminish these genres or to reduce their works to a list of influences. Nor am I offering an invitation to embrace the esoteric as literal truth. Instead, I'm reminding everyone of just how permeable the boundary between belief and imagination has always been and how fantasy, in particular, has long served as a vessel for metaphysical speculation, even when dressed in the garb of swords and sorcery or rocket ships and ray guns. Perhaps this is one of the reasons these genres endure: they don’t merely entertain; they echo the ancient human desire to find meaning in a world that so often seems devoid of it.Retrospective: Alien Module 7: Hivers

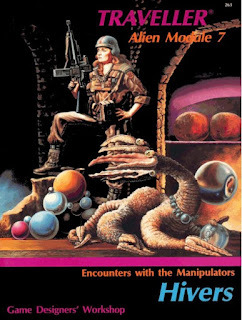

By the time Alien Module 7: Hivers was published in 1986, the Traveller role-playing game was approaching its tenth anniversary. Game Designers’ Workshop (GDW) already had a great deal of experience in producing sourcebooks to the major alien races of the Third Imperium, producing some of the line’s most inventive and distinctive supplements. The Hivers, among the most enigmatic of Traveller’s aliens were a natural fit for this deep-dive treatment. Their inscrutable nature and radical departure from humanoid norms demanded a module that could capture their alien essence while expanding the possibilities of the game itself.

Unlike the Vargr, with their wolf-pack dynamics dressed in science-fictional trappings, or the Aslan, who embodied the archetype of the "proud warrior race," the Hivers defied easy categorization. They were, in a word, strange – non-humanoid, non-violent, intellectually aloof, and relentlessly meddlesome. Their radial, starfish-like physiology and their communication through color changes and body posture evoked a biology more akin to deep-sea creatures than traditional sci-fi aliens. Their penchant for subtle, centuries-long manipulation of other species felt like something drawn from the cosmic visions of Olaf Stapledon or the surreal imaginings of Cordwainer Smith (even though the book openly admits the debt owed to Larry Niven’s Pierson’s Puppeteers and Outsiders). Despite this, the Hivers were a wholly unique creation, their oddity amplified by a psychology that prioritized intricate social engineering over direct action.

The success of Alien Module 7: Hivers in giving shape and substance to such an unconventional species is a testament to the talents of its principal authors: William H. Keith, J. Andrew Keith, Loren Wiseman, and Traveller creator Marc Miller. Structured like its predecessors, the module is divided into sections covering history, physiology, psychology, society, technology, along with rules for generating Hiver characters. Yet what immediately sets it apart is how bizarre its subject matter is. The Hivers are not “rubber suit” aliens defined by a single cultural quirk. Their biology is profoundly non-human: they reproduce almost accidentally without pair bonding or even emotional investment, communicate via mechanisms no human could intuitively grasp, and perceive the universe through a lens shaped by their intense curiosity. Their society, too, defies familiar models. Rather than being organized around governments or hierarchies, Hiver civilization is a loose tapestry of individuals pursuing esoteric, often opaque "topics" – long-term investigations that might span centuries and often involve subtly steering entire civilizations toward particular ends. One cannot help but draw comparisons to the Bene Gesserit of Dune, with their millennia-spanning schemes or even Lovecraft’s Elder Things, with whom the Hivers share a faint physical resemblance, though without the malice or cosmic horror.

What further distinguishes Hivers from earlier Alien Modules is its refusal to reduce its subject to easily digestible tropes. The Hivers are not warriors, traders, or pirates; they are manipulators, schemers, and architects of destiny. Their commitment to nonviolence is not a weakness but a cornerstone of their civilization, shaping their every interaction. They are not pacifists in the conventional sense but they are deeply opposed to overt conflict, preferring to neutralize threats through careful, almost surgical social redesign. The module provides a vivid example of this approach in their centuries-long maneuvering against the K’kree, their militant, herbivorous neighbors, a species almost as alien to human eyes as themselves.

As presented, a campaign involving the Hivers is unlikely to revolve around the familiar beats of firefights, starship chases, or planetary exploration. Instead, it gestures toward something slower and subtler: espionage, cultural subversion, and interstellar diplomacy of a particularly insidious kind. However, this is also where the module falters. While it does provide broad advice on running Hiver-centric adventures, it rarely offers the kinds of concrete examples that would help a referee bring these high-concept scenarios to life at the table. The included adventure, “Something Stinks!,” is brief and unmemorable, more a sketch than a scenario and one that never quite demonstrates how to make the Hivers’ unique qualities matter in play. This is a common flaw in the Alien Module series: strong ideas paired with underdeveloped tools for implementation.

That said, one of the book's more subtle successes lies in how it situates its subject within the wider Traveller setting without dulling their strangeness. The Hivers’ influence on the Imperium is indirect but pervasive, shaping events from the shadows through trade agreements, cultural shifts, and strategic nudges – at least, that’s what they’d like you to believe. This ambiguity is where the module’s potential becomes most intriguing. The Hivers are not just another species; they are potentially a vehicle for a different kind of science fiction roleplaying, one that rewards speculation, inference, and even conspiracy-minded thinking. The fact that they remain difficult to grasp even after 48 pages of focused attention feels less like a failure and more like a feature, though one that may frustrate as often as it inspires.

In the end, Alien Module 7: Hivers is an ambitious but uneven entry in the Traveller canon. It introduces a compellingly alien species with a richly imagined culture and worldview, yet it struggles to translate that material into content easily usable in play. The ideas are strong and the writing imaginative, but too often the referee is left to do the heavy lifting. Still, for those intrigued by the prospect of a campaign built around manipulation, subtlety, and long-term consequences, the module offers a tantalizing foundation. Like the Hivers themselves, it prefers to hint and suggest rather than declare outright. Whether that is a strength or a weakness will depend on the kind of game you wish to run.June 10, 2025

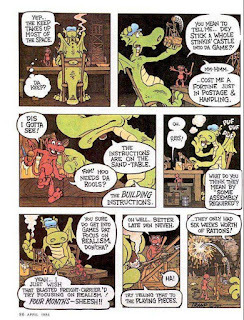

Smoke Rings and Sorcery: An Ode to Wormy

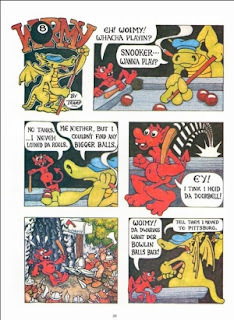

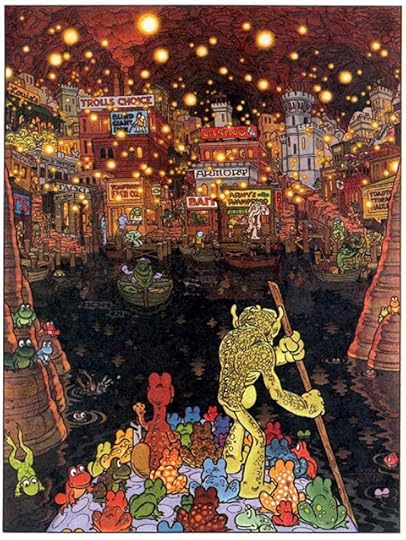

Among the many delights of flipping through issues of Dragon magazine from my youth is getting the chance to see Dave Trampier's Wormy comic strip once again. Long before I was conscious of the names of any of the artists who appeared in my favorite RPG products, I knew Wormy. Even among the clutter of rules variants, advertisements, fiction, and the occasionally bombastic editorials that defined Dragon during the years when I most avidly read it, Wormy stood out, in large part because it was so strange. It was a peculiar, beautiful little world unto itself, filled with pool-playing dragons, cigar-chomping ogres, and an imp who spoke with the laid-back confidence of a veteran hustler. It was, in short, utterly unlike anything else in the pages of Dragon and it fascinated me – in large part because I didn't fully understand it or its continuing storyline, having picked it up many issues after it first began.

Among the many delights of flipping through issues of Dragon magazine from my youth is getting the chance to see Dave Trampier's Wormy comic strip once again. Long before I was conscious of the names of any of the artists who appeared in my favorite RPG products, I knew Wormy. Even among the clutter of rules variants, advertisements, fiction, and the occasionally bombastic editorials that defined Dragon during the years when I most avidly read it, Wormy stood out, in large part because it was so strange. It was a peculiar, beautiful little world unto itself, filled with pool-playing dragons, cigar-chomping ogres, and an imp who spoke with the laid-back confidence of a veteran hustler. It was, in short, utterly unlike anything else in the pages of Dragon and it fascinated me – in large part because I didn't fully understand it or its continuing storyline, having picked it up many issues after it first began.

Wormy's debut (in issue #9, September 1977) occurred when Dragon was still very much in its formative years. Indeed, the hobby of roleplaying itself was barely out of its own infancy and TSR’s flagship magazine was still trying to figure out what kind of publication it wanted to be. Early issues mixed game material with essays, fiction, and humor. Comics became a regular feature before long, with J.D. Webster's Finieous Fingers being one of the more well-known of the bunch, even though it ended its run about a year before I started reading Dragon. But Wormy stood out as something different. It was never simply an in-joke for gamers nor a gag strip loosely inspired by fantasy tropes. Instead, it presented a fully realized fantasy world rendered in lush color and with a distinct artistic sensibility.

Wormy's debut (in issue #9, September 1977) occurred when Dragon was still very much in its formative years. Indeed, the hobby of roleplaying itself was barely out of its own infancy and TSR’s flagship magazine was still trying to figure out what kind of publication it wanted to be. Early issues mixed game material with essays, fiction, and humor. Comics became a regular feature before long, with J.D. Webster's Finieous Fingers being one of the more well-known of the bunch, even though it ended its run about a year before I started reading Dragon. But Wormy stood out as something different. It was never simply an in-joke for gamers nor a gag strip loosely inspired by fantasy tropes. Instead, it presented a fully realized fantasy world rendered in lush color and with a distinct artistic sensibility.What immediately set Wormy apart was, of course, Trampier’s art. Nowadays, we all celebrate Trampier from his iconic work on the AD&D Player’s Handbook and the Dungeon Master’s Screen. His style is clean, expressive and rich in texture and character. Wormy carried those same qualities into serialized comic form, but with an added flourish of visual wit and playfulness. The strip was never slapdash or haphazard. Trampier’s panels were packed with detail, his character designs expressive, his linework confident. Each page was a feast for the eyes and even when the plot meandered a bit (as it regularly did), the visuals carried the reader along to such an extent that he didn't care. I know I didn't, even though, as I said, it wasn't always clear to my younger self just what was happening in many installments.

The tone of the strip is one of its greatest charms. Wormy is unquestionably fantasy, but it’s fantasy as seen through a haze of cigar smoke and the low hum of a barroom pool table. Its characters speak in a colloquial American idiom that lends the strip a grounded, personable quality. One never gets the sense that Wormy or Ace or the ogres and trolls with whom he shares his world are interested in epic quests or noble deeds. They’re more likely to be plotting a scam, hustling a demon, or arguing about who’s buying the next round. This sense of the fantastical-as-everyday-life gives Wormy much of its charm and humor, not to mention its distinctiveness from the other comics that appeared alongside it in Dragon.

The tone of the strip is one of its greatest charms. Wormy is unquestionably fantasy, but it’s fantasy as seen through a haze of cigar smoke and the low hum of a barroom pool table. Its characters speak in a colloquial American idiom that lends the strip a grounded, personable quality. One never gets the sense that Wormy or Ace or the ogres and trolls with whom he shares his world are interested in epic quests or noble deeds. They’re more likely to be plotting a scam, hustling a demon, or arguing about who’s buying the next round. This sense of the fantastical-as-everyday-life gives Wormy much of its charm and humor, not to mention its distinctiveness from the other comics that appeared alongside it in Dragon. In this, Wormy mirrors the culture of early roleplaying itself. The early hobby, as reflected in the pages of Dragon, was a strange admixture of wargamers, fantasy and science fiction fans, history buffs, and countercultural weirdos. This was a time before fantasy had hardened into genre orthodoxy, when anything could happen and often did. The world Trampier presented in Wormy feels like a campaign gone delightfully off the rails: a sandbox setting where the players long ago stopped caring about the dungeon and are now embroiled in a decades-long tavern brawl. For me, that was a big part of what I found so compelling about Wormy. It was so unlike my then-narrow conception of "fantasy" that I couldn't help but keep reading.

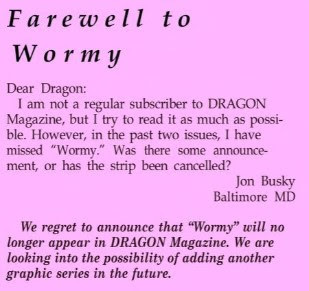

Over time, Trampier introduced a larger story into the strip. There were plots and schemes in motion and strange characters lurking just out of frame. Readers were teased with glimpses of the larger world beyond Wormy’s abode and the smoky dens of the trolls. Then, just as suddenly as it had begun, Wormy vanished. Trampier’s final installment appeared in Dragon #132 (April 1988), ending mid-story. He never offered a public explanation. Other than the following, which appeared in issue #136 (August 1988), TSR never provided an explanation for what had happened:

Wormy, along with its creator, David Trampier, vanished without a trace.

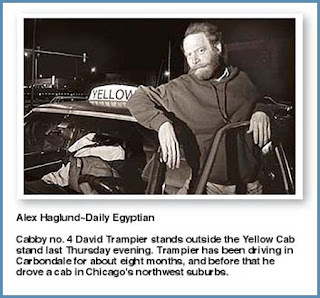

Wormy, along with its creator, David Trampier, vanished without a trace.This abrupt disappearance only deepened the comic strip’s allure. In the years that followed, fans spun wild theories: Was Trampier dead? Had he severed all ties with the gaming world? Or was it something darker? For decades, the mystery endured, unanswered. Then, in 2002, word emerged that Trampier was alive, living a quiet life in southern Illinois as a taxi driver. He had steadfastly declined all invitations to return to art or gaming until 2014, when he agreed to showcase some of his original artwork at a local Illinois game convention. Tragically, just three weeks before the event, he died suddenly at age 59.

In hindsight, Wormy feels like a microcosm of an entire era in fantasy gaming, a time that was raw, personal, and unapologetically chaotic. The strip was a labor of love, brimming with anarchic energy, improvisational flair, and unfiltered creativity. Like the Dragon magazine of its heyday, Wormy was gloriously messy, fiercely idiosyncratic, and utterly brilliant in its refusal to conform or explain itself.

In hindsight, Wormy feels like a microcosm of an entire era in fantasy gaming, a time that was raw, personal, and unapologetically chaotic. The strip was a labor of love, brimming with anarchic energy, improvisational flair, and unfiltered creativity. Like the Dragon magazine of its heyday, Wormy was gloriously messy, fiercely idiosyncratic, and utterly brilliant in its refusal to conform or explain itself.As the hobby grows ever more polished and commercialized, Wormy stands as a vibrant reminder of its roots, a time when oddballs and iconoclasts like Trampier defined its spirit. More than a relic, Wormy embodies the untamed passion and fearless imagination of those who dared to be unapologetically strange. It captures a moment when the heart of gaming pulsed with individuality, free from the gloss of corporate agendas.

Whenever I leaf through old issues of Dragon, I find myself missing Wormy – not just the comic, but what it stood for: the spirit of unfiltered creativity, the joy of irreverence, and the beautiful imperfections of a world made by and for dreamers. In remembering Wormy, we remember that the true magic of roleplaying lies not in polished production values or grand designs, but in the bold, eccentric, and often messy adventures we undertake with one another .

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers