James Maliszewski's Blog, page 15

June 24, 2025

The Petal Throne Has Thorns

Recently, I sent a message to the players on our House of Worms campaign Discord server. It was, in essence, a warning.

This is not meant to frighten anyone.

Now that I've succeeded in frightening everyone, here it is: From this point on in the campaign, the gloves are off.

By that I mean, we're nearing the End and that means anything can happen, including characters dying. Obviously, there are means to bring them back cough, *cough, cough Aíthfo* but there's no guarantee of that, especially given how things are going. I bring this up only because I'm committed to the campaign's conclusion being a tense and uncertain one in every way. Though I've never held back in letting the dice fall where they may *cough, cough, Aíthfo*, things may nevertheless get even nastier than they ever have before and I feel an obligation to remind everyone that no one has Plot Armor.

Have a nice day. 😊

It’s a bit tongue-in-cheek, but the underlying message is serious: after more than a decade of weekly play, the House of Worms campaign is approaching its conclusion. The characters, most of whom have been in play for years, are not guaranteed a happy ending, let alone a heroic one. They can fail. They can die. They might even die pointlessly, offhandedly, from a bad roll at the wrong moment.

That’s all par for the course in a proper old school RPG campaign, of course, but I felt compelled to remind the players. As I’ve likely said many times over the years, House of Worms is light on dice rolls outside of combat and combat itself is rare outside the underworld. Most sessions consist almost entirely of roleplaying in one form or another and the players are very good at it. More often than not, they resolve their problems through conversation, manipulation, and clever schemes rather than through swordplay or spellcraft. Much as I love that – and I do, given my longstanding dislike of combat – I sometimes worry it’s made them a little too comfortable. A little too safe.

From what I read online and have sometimes even observed "in the wild," there's a tacit expectation in a lot of contemporary gaming circles that player characters are protagonists will, therefore, reach the end of a campaign. They might suffer, they might be scarred, but they'll get there. There's an implicit contract between referee and player that, so long as you show up and play your character, you'll at least survive to the final scene. Old school play usually doesn't work out that way and, at least in my interpretation of it, Tékumel especially doesn’t work that way.

Tékumel is a setting where the gods are real, inscrutable, and often indifferent. It's a place of Byzantine scheming, hidden pacts, and ancient horrors. A misplaced word or an ill-advised alliance can unravel everything you've worked toward – and that’s glorious. As I conceive it, a Tékumel campaign should end the way it began: full of mystery, danger, and unpredictability. There's n script; there’s no "true ending." There's only what the players do and what the dice say about it.

I've always tried to referee the House of Worms campaign in a way that respects the players' choices – as well as the consequences of those choices. That doesn’t mean I'm out to kill their characters for shock value or for sport. However, it does mean that no character is safe just because they’re "important." If anything, being important only puts a larger target on a character's back. Indeed, that's been the pattern of this campaign since its inception in March 2015: each time the characters succeed, there's been an escalation in the stakes and the strength of the opposition. Where once they contended with local matters of small moment, now they're at the very heart of an imperial succession crisis, one that involves not just earthly power politics but the machinations of gods and demons.

In playing House of Worms, what I’ve come to appreciate most about it and, by extension old school RPG campaigns more generally, is their fragility. There’s no safety net, no rewind button. The stakes are real and when the players realize that, when they know the character they've played for literally years could disappear into the void at any moment, the impact on play is considerable. That’s when the game transcends mere mechanics and becomes something else: a shared experience of genuine risk and reward.

So yes, the gloves are off, but they were never really on to begin with.

Have a nice day. 😊June 23, 2025

REPOST: The Articles of Dragon: "Special Skills, Special Thrills"

Of all the iconic classes of D&D, the cleric is the one that sticks out like a sore thumb. Whereas the fighting man, the magic-user, and even the thief are all pretty broad archetypes easily -- and non-mechanically -- re-imagined in a variety of different ways, the cleric is a very specific type of character. With his heavy armor, non-edged weapons, Biblical magic, and power over the undead, the cleric is not a generic class, recalling a crusading knight by way of Van Helsing. There's thus a distinctly Christian air to the cleric class, an air that increasingly seemed at odds with the game itself, which, as time went on, distanced itself from its earlier implicit Christianity and embraced an ahistorical form of polytheism instead.

Of all the iconic classes of D&D, the cleric is the one that sticks out like a sore thumb. Whereas the fighting man, the magic-user, and even the thief are all pretty broad archetypes easily -- and non-mechanically -- re-imagined in a variety of different ways, the cleric is a very specific type of character. With his heavy armor, non-edged weapons, Biblical magic, and power over the undead, the cleric is not a generic class, recalling a crusading knight by way of Van Helsing. There's thus a distinctly Christian air to the cleric class, an air that increasingly seemed at odds with the game itself, which, as time went on, distanced itself from its earlier implicit Christianity and embraced an ahistorical form of polytheism instead.For that reason, there were growing cries among some gamers to "fix" the cleric. In this context "fix" means change to make it less tied to a particular religion, in this case a particular religion the game itself had eschewed. The first time I recall seeing an "official" answer to these cries was in Deities & Demigods , where it's noted that the clerics of certain deities had different armor and/or weapon restrictions than "standard" clerics. A few even got special abilities reflective of their divine patron. This idea was later expanded upon by Gary Gygax himself in his "Deities & Demigods of The World of Greyhawk" series of articles, which I credit with giving widespread attention to this idea. I know that, after those articles appeared, lots of my fellow gamers wanted to follow Gary's lead and tailor their cleric characters to the deities they served, an idea that AD&D more formally adopted with 2e in 1989.

In issue #85 (May 1984) of Dragon, Roger E. Moore wrote an article entitled "Special Skills, Special Thrills" that also addressed this topic. Moore specifically cites Gary's articles as his inspiration and sets about providing unique abilities for clerics of several major pantheons. These pantheons are Egyptian, Elven, Norse, Ogrish, and Orcish – a rather strange mix! Of course, Moore intends these to be used only as examples to inspire individual referees. Likewise, he leaves open the question of just how to balance these additional abilities with a cleric's default ones. He notes that Gygax assessed a 5-15% XP penalty to such clerics, but does not wholeheartedly endorse that method himself, suggesting that other more roleplaying-oriented solutions (ritual demands, quests, etc.) might work just as well.

Like a lot of gamers at the time, I was very enamored of the idea of granting unique abilities to clerics based on their patron deity. Nowadays, I'm not so keen on the idea, in part because I think the desire for such only underlines the "odd man out" quality of the cleric class. Moreover, nearly every example of a "specialty cleric" (or priest, as D&D II called them) still retains too much of the baseline cleric to be coherent. Why, for example, would a god of war be able to turn the undead? Why should almost any cleric wear heavy armor and be the second-best combatant of all the classes? The cleric class, even with tweaks, is so tied to a medieval Christian society and worldview that it seems bizarre to me to use it as the basis for a "generic" priest class. Far better, I think, would be to have individual classes for priests of each religion or, in keeping with swords-and-sorcery, jettison the class entirely.

War!

As you can probably tell from both of my earlier posts today, there are soon going to be some large, pitched battles in my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. This isn't something I'd imagined some months ago, when we began entering the final stages of the campaign, but here we are. This turn of events makes sense, of course, given the way events are unfolding. However, I can't deny that this prospect fills me with a bit of apprehension. As I've said on many occasions over the years, I've never been a wargamer of any kind, despite my fascination with and some knowledge of military matters. I say this with some regret, both because this lacuna in my game education has no doubt skewed my perspective on certain things and because it leaves me somewhat at loss in knowing how to handle occasions of mass combat within a RPG.

As you can probably tell from both of my earlier posts today, there are soon going to be some large, pitched battles in my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. This isn't something I'd imagined some months ago, when we began entering the final stages of the campaign, but here we are. This turn of events makes sense, of course, given the way events are unfolding. However, I can't deny that this prospect fills me with a bit of apprehension. As I've said on many occasions over the years, I've never been a wargamer of any kind, despite my fascination with and some knowledge of military matters. I say this with some regret, both because this lacuna in my game education has no doubt skewed my perspective on certain things and because it leaves me somewhat at loss in knowing how to handle occasions of mass combat within a RPG.That's why I'm turning to you, my readers, for thoughts and suggestions on how you have handled wars and large-scale battles in your roleplaying game campaigns. What rules or approaches did you use and how well did they work? Did they mesh well with the RPG you were playing? I'm honestly curious about every aspect of this question, since I have such limited experience with it in my own campaigns and would appreciate learning from those of you who've successfully incorporated mass combat into yours.

That said, I should make a few things clear about my own preferences as a referee. Between my dislike of combat as an activity in itself and my feeling that most RPGs have too many rules, I have a natural aversion to any kind of mass combat system that plays out like a wargame. If I wanted to play a wargame, I'd play a wargame. What I want – and this may be impossible – is a solution that doesn't require me or the players to learn a whole new set of rules to simulate their characters' involvement in a big battle. Additionally, I'd like for what the characters do to have an effect on the outcome of the battle, even if they're not directly involved in everything that happens. I realize this is likely asking a lot, but I have lots of smart and knowledgeable readers, so maybe one of you can point me in the right direction.

To date, the only RPG I've ever played that had a decent set of mass combat rules was Pendragon and, even there, I wasn't wholly satisfied with the results. The main virtue of Pendragon was that the participation of the player characters still used the standard combat rules and the results of their individual battles had some impact on the final outcome of a larger fight. I didn't have to keep track of lots of wargame-y rules to adjudicate the battle satisfactorily. That's more or less what I want here, though, as I said, I may be asking for too much.

Your thoughts on this matter are thus greatly appreciated.

The Battle of Béy Sü

From an address by Prince Eselné Tlakotáni to his legions on the steps of the Palace of War just prior to commencing their assault on the Temple of Sárku (13 Fésru 2360 A.S.):

"I will not lie to you. This path I have chosen leads into fire. There will be war. Blood in the streets. Temples razed, banners burned, clans shattered. I do not deny it: I expect it."

"But we must walk it anyway."

"For too long, we have whispered that Tsolyánu is 'eternal,' not because she is strong, but because we fear what will happen if she changes. We call her 'timeless' when what we really mean is stagnant. We call her 'harmonious' when what we really mean is choked. We call her 'pious' while we let the temples devour her from within."

"We have smoothed over every fracture with ritual. Buried every danger beneath scrolls. We’ve let the high clans rot behind lacquered gates and the bureaucrats nest like syúsyu-lizards in the rafters of the Golden Tower. And when the choosing of an emperor becomes not a moment of clarity, but a pageant of manipulation, then we are no longer ruled by 'tradition.' We are ruled by cowardice dressed in antique finery."

"I am not a reformer. I am not a philosopher. I am a soldier. I know what war looks like — and still I choose it."

"Béy Sü is nearly four hundred years overdue for Ditlána. Every brick in this city knows it. But perhaps it is not just Béy Sü that must be razed and reborn. Perhaps the whole Empire must be broken, so it can live again."

"If that is madness, then better a madman with clean hands than another schemer who calls ruin peace."

June 22, 2025

Campaign Updates: Two for the Road

That "real life" thing that I'm sure everyone has heard of does indeed exist and it's been keeping me busy over the last few weeks. It's apparently been doing the same thing to a lot of my players, too, hence my current campaigns have convened fewer times than I had hoped. Nevertheless, we did play several sessions of both Barrett's Raiders and House of Worms. Dolmenwood, alas, remains in a brief stasis; with luck, it will resume this week. In the meantime, here's the latest news from both Fort Lee, Virginia and Béy Sü, Tsolyánu:

Barrett's RaidersArmed with Specialist Huxley's confession, Major Hunter decided that now was the time to approach both Lt. Nolan Bennett in logistics, along with his superior, Captain Reginald Tolen. She started with Bennett, who attempted to obfuscate the issues at hand, claiming that any irregularities could be chalked up to simple "clerical error" and the stress of trying to operate a military base "under difficult conditions." Hunter then confronted him with what Huxley told her, which cause Bennett to take a different tack. He admitted that Tolen probably had a hand in what's happening, but assured her that it's because "the captain's a good guy" who's "just trying to help people anyway he can." There's nothing sinister in it and it'd be a mistake to expose Tolen, since it'd probably land him in the stockade.

Hunter suspected this still wasn't the whole truth. She used other evidence she'd collected from paperwork and reports to demonstrate that Bennett himself must have been involved too. Bennett made a few more attempts to weasel out of these accusations before admitting that, yes, he'd used both Tolen and Huxley for his own betterment. He'd been contacted by a New America adherent who made him an offer: funnel war materiel from Fort Lee to him and he'd ensure that, when the time came, Bennett would be given a meal ticket and a position of safety "out west." Bennett claimed he didn't care about New America's ideology, only that he had a future. "Look around. Open your eyes. USMEA doesn't have what it takes to put this country back together again. I decided to back the winner."

When confronted with these facts, Captain Tolen was appalled. He openly admitted that, yes, he had made arrangements, through Bennett, to send "extra" supplies to civilian communities in need of them – but he swore he did not authorize the sending of war materiel to anyone, let alone New America. He felt betrayed, though he made no bones about the fact that he was ultimately to blame for this situation. Tolen took full responsibility and offered to turn himself in to the Provost Marshal, Colonel Kearns. Major Hunter said that she would speak to Kearns first, but, in the meantime, he and Bennett would be placed under guard.

Kearns was not surprised to learn that Tolen was involved. He said that the captain was a "naive bleeding heart" but not a bad a man. Fort Lee owed a lot to his work to keep it together, but that did not excuse his "reckless" behavior. Ultimately, though, the fault lay with General Summers, the base commander, who "cared more about looking good for Norfolk than doing his job." Summers, he explained, was a desk general, who had never seen combat and now, with all the soldiers returning from Europe, was worried he might be replaced "by someone with actual military experience." Summers always preferred to paper over problems rather than deal with them.

Hunter confirmed some of what Kearns claimed when she and Lt. Col. Orlowski presented MLG-7's report directly to Summers. The general praised them for getting to the bottom of the problem and that they had done so quietly. Summers then said that they were probably keen to leave Fort Lee and continue on their journey. He asked several times when they planned to leave and if there were anything his office could do to speed them on their way. This suggested that Col. Kearns had been correct in his assessment of the general: he wanted to be sure no one in Norfolk got wind of this serious breach of security that had happened under his watch.

Hunter and Orlowski explained they'd be leaving tomorrow, which pleased Summers. He thanked them again and sent them on their way. Of course, Spc. Huxley was scheduled to make another supply run the next day, too. Now that he had been found out, New America would realize something had happened and they might change up their local operations. That didn't sit well with Hunter and Orlowski, who decided that, as part of the departure the next day, MLG-7 would look into this dangling thread personally.

House of Worms

The characters made their way to a safe location known to him through Nebússa's contacts in the Omnipotent Azure Legion. There, they took stock of the artifacts Míru had left for Kirktá and opened the chest of the topaz god to remove the priest of the One Other they'd place in stasis there. Normally, a living being struck by the beam of an excellent ruby eye is held in suspended animation unharmed until he is struck again. This time, though, that did not seem to be the case. When Míru was released, he appeared lifeless – not dead exactly but certainly not alive either. It immediately occurred to Kirktá that, having lived a double life within the Temple of Belkhánu for so long, Míru had undoubtedly learned one or more spells that would enable him to transfer his consciousness from one body to another. He had probably done so moments before he was struck by the excellent ruby eye. If so, he was still alive and working toward his own purposes.

This was unfortunate as Míru knew not only more about Kirktá's early life and purpose but also about the seven items he'd gathered for him to use. The items consisted of: a small, uncut piece of onyx; a small wooden statue of Halúb, "the Knower of Hidden Truths," an obscure aspect of Belkhánu; a polished disc of gray metal framed in bone; a thin leather scroll, warm to the touch and slight pulsating; a mummified finger; a funerary mask with a single eye slot in the brow; and a golden statuette of an ancient ruler whose face has been erased by time. Using the spell seeing other planes, Kirktá determined that the onyx, the disc, and the mask all showed strong connections to the Planes Beyond, while the others were much less potent.

Kirktá set about examining the statue of Halúb first, soon discovering that it was actually a reliquary inside of which was a scroll wrapped in silk. The scroll was made of a sturdy, thin material that was completely black. When viewed in darkness, however, the blackness "fell away," revealing dense text written in Classical Tsolyáni. The text turned out to be the terms of the pact entered into by the First Tlakotáni with the One Other. According to those terms, the emperor-to-be offered the souls of his line to the One Other in exchange for the eternal protection of the fortress of Avanthár against all external threats. So long as the Tlakotáni continued to offer the souls of princes defeated in the Kólumejálim, the One Other would ensure Avanthár never fell.

As an expert demonologist, Keléno scoffed at the pact, calling it "sloppy." He explained that, among other things, there were too many loopholes in the text, specifically that it did not spell out the consequences if one party breaches it. He said he would never enter into such a contract with a demon, let alone a pariah god. Clearly, there must be some details that were missing, because it's difficult to imagine that the pact would have held up for more than 2000 years without either side failing to live up to it. That's when Nebússa began to wonder whether or not it was already in a state of breach, which might explain why Dhich'uné was so keen to establish new terms for it.

Speaking of Dhich'uné, because he had offered protection to many priests of Belkhánu fleeing the razing of their temple, Eselné turned his sights onto the Temple of Sárku. He had ordered his legions, including the cohort led by Grujúng into position to attack it. This concerned the other characters, who worried that such an attack might well play into Dhich'uné's hands. They rushed to the Palace of War, seeking an audience with General Kéttukal to bring their worries to him. As it turned out, Kéttukal had been looking for them. He explained that Dhich'uné had made a formal request for a parley and asked that Kirktá be the one to receive it.

Kirktá, along with Keléno and Nebússa, made their way to meet the Worm Prince. There, he delivered his ultimatum: call off the attack or else he would raise an army of the undead to defend him and turn the capital into a tomb. Additionally, he tempted Kirktá to join him so that he might finally learn the truth of who he is and why that truth was hidden for so long. Kirktá did not give in, despite his intense curiosity. Instead, he and the others returned to Eselné and Kéttukal to prepare for all-out war.

June 19, 2025

Stuck

If you’d told my younger self that, by middle age, Star Wars, Star Trek, Dungeons & Dragons – all the things I loved as a boy – would not only still exist but would be huge entertainment "brands," I doubt I’d have believed you. I certainly wouldn’t have believed I’d no longer care about them. Worse, I never would have imagined I’d feel repulsed by what they’ve become.

If you’d told my younger self that, by middle age, Star Wars, Star Trek, Dungeons & Dragons – all the things I loved as a boy – would not only still exist but would be huge entertainment "brands," I doubt I’d have believed you. I certainly wouldn’t have believed I’d no longer care about them. Worse, I never would have imagined I’d feel repulsed by what they’ve become.And yet, here we are.

Plenty of commentators have observed a phenomenon sometimes called “stuck culture” and I think that captures part of my malaise. Contemporary pop culture seems either unable or unwilling to move on from the past. Instead, it recycles, reboots, and repackages the same "intellectual properties" – a phrase I feel unclean even typing – over and over again, as though what we truly need is just one more sequel, one more origin story, one more “gritty reimagining” of a once-beloved character or setting.

This cultural stagnation is especially glaring in the realm of the nerds, where hobbies were once defined by originality and creativity. Now? They're more often defined by compulsive repetition and the embalmed echoes of past glories.

Don’t misunderstand me: there’s nothing wrong with nostalgia. Remembering the things that once brought us joy is natural, even humanizing. However, there’s a difference, in my opinion, between nostalgia and necromancy. So much of popular culture today, particularly nerd culture, feels like it’s reanimating corpses. Bigger budgets, flashier effects, and algorithmic polish don’t bring these creations back to life. They only parade them around, lifeless and hollow, like mummified icons. The result isn’t a return to something vital or real. Instead, it’s a grotesque simulacrum, stripped of its original context, meaning, and soul.

In the age of content algorithms, our past preferences become templates for future production. Innovation is replaced by optimization – and what’s being optimized isn’t storytelling or artistry, but you. Or rather, your predictable patterns of engagement. If you once loved, say, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, they'll feed you a dozen pale imitations, each more toothless, more risk-averse, and more emotionally flat than the last. If you liked elves and dungeons in 1982, the machine will churn out endless corporate flavors of the same, carefully drained of the strangeness and wonder that once made them sing.

This is apparent even in roleplaying games. There was a time when RPGs were gloriously, sometimes chaotically, diverse. Every few months brought some new idea, some strange world, some half-baked but fascinating mechanic. Some of it was brilliant, some of it was garbage, but all of it felt alive. Today? Most major RPG products are variations on a narrow set of tropes established decades ago. Even the Old School Renaissance, of which I count myself a part, often falls prey to the same trap: remaking, rehashing, repeating.

So when did creativity give way to caretaking? When did our hobby stop being about imagining new worlds and become a museum of preserved brands?

It wasn’t always this way. Nerd subcultures were once genuinely weird – offputting, insular, and proudly obscure. They were difficult to access and defiantly uncool and that very inaccessibility acted as a crucible, forging originality and independence. But the rise of the Internet, and especially social media. has flattened all subcultures. Everything is now accessible, marketable, and smoothed out for mass consumption. Because nerds were among the earliest adopters of these technologies, nerd culture may have suffered the most from this transformation.

The result is a creeping homogenization. “Fantasy” now means elves and dragons. “Sci-fi” means space wizards. Every new game must have a "brand identity," a "product roadmap," a social media presence. Anything that doesn’t fit the mold is quietly ignored, regardless of how original or inspired it might be.

What we’re losing in this cycle of endless recycling isn’t just novelty but meaning. The worlds we once explored, whether in a galaxy far, far away or deep beneath a ruined castle, mattered because they were new. They challenged our imaginations. They opened doors we didn’t even know were there. When everything becomes a remix of a remix, that sense of discovery is lost. That may be the real tragedy – not simply that nerd culture has changed, but that it has ceased to move on. It no longer dares to venture into the unknown. It circles the same drain, hoping that the next familiar logo will somehow rekindle the old spark.

But it won’t. It can’t.

The antidote to stuck culture isn’t rage and it isn’t despair. It’s refusal. Refusal to let our cultural memory be mined for spare parts. Refusal to accept brand management in place of imagination. Refusal to mistake familiarity for worth.

There are still creators out there doing strange, beautiful, uncompromising work. There are still games being written, books being published, ’zines being assembled that don’t give a damn about algorithms or intellectual property portfolios. Seek them out. Support them. Better yet, make your own.

Let the past be the past, not a franchise."I Am Prepared to Teach Him the Proper Rites."

©2011–2025 Jeff Dee“Ah, Kirktá. Sit. Not as adversaries, but as brothers, as sons of the emperor – as men who remember what peace feels like.”

©2011–2025 Jeff Dee“Ah, Kirktá. Sit. Not as adversaries, but as brothers, as sons of the emperor – as men who remember what peace feels like.”“Peace. That is all I wish, though Eselné does not believe me. But is it not a good ambition for one who dwells among the dead. Who better to know the true meaning of peace?”

“Everything I have done — the cloistered councils, the careful alliances, the sheltering of those who now flee from Eselné’s wrath — I have done to preserve the Empire, not to destroy it. It is Eselné who fans the flames. Eselné who tears at the old ways. Tell me, Kirktá: who breaks the Concordat? Who has sent his legions to desecrate one temple in his blind pursuit of dominion and now threatens another?”

“Not I.”

“You know he cannot win, not without destroying all that Tsolyánu is. But you still stand at the crossroads. I know who you are. I know what you are. I know where you came from. I know why you were hidden.”

“Only by walking beside me will your skein at last be made whole. Only I can draw the threads together – the frayed, the hidden, the ones others tried to cut. Let me show you the pattern behind your life. Don’t you wish to know why you were woven at all?"

“But if you decline, if you cling to Eselné’s banner, then I have no choice but to act and to act swiftly."

"You know, of course, that Eselné is not the only prince with legions in Béy Sü.”

“Though I suppose it would be more honest to say that I have legions under Béy Sü – beneath its stones, its vaults, its ancient crypts. There are soldiers sleeping there in the dust who swore undying oaths to the Petal Throne before Eselné’s name was ever spoken. If he wishes to turn this city into a tomb, I am prepared to teach him the proper rites.”

“Tell him that. Or don’t. He will learn soon enough. But you still have a choice: stand where your true fate calls you. Stand beside me.”

"Now, go."June 18, 2025

Dragonlance at the End of the World

One of many things that doesn't always come through in my campaign update posts are the little moments of roleplaying and character development that are, for me anyway, why I continue to participate in this hobby after so many decades. Reading those posts and the supplementary ones that draw attention to larger developments within them, one might well think the Big Stuff is all that matters to me. Of course, the Big Stuff does matter to me, especially in my House of Worms and Barrett's Raiders campaigns, where political, social, and religious struggles are important drivers of the action. Even so, it's the characters who matter most to me. They are, after all, the means by which my wonderful players interact with the situations I set before them and I appreciate the added texture they can add to the game world.

One of many things that doesn't always come through in my campaign update posts are the little moments of roleplaying and character development that are, for me anyway, why I continue to participate in this hobby after so many decades. Reading those posts and the supplementary ones that draw attention to larger developments within them, one might well think the Big Stuff is all that matters to me. Of course, the Big Stuff does matter to me, especially in my House of Worms and Barrett's Raiders campaigns, where political, social, and religious struggles are important drivers of the action. Even so, it's the characters who matter most to me. They are, after all, the means by which my wonderful players interact with the situations I set before them and I appreciate the added texture they can add to the game world.An amusing case in point is Corporal Wayne "Rocketman" Schweyk. Rocketman was originally a back-up character, introduced during the unit's time in the Free City of Kraków. All the players had a back-up character, both to fill out the unit's complement, but also as insurance in case one of the "main" characters died in combat or through some other means. Rocketman, as his name suggests, had been part of a Multiple Launch Rocket System crew during the earlier stages of the Twilight War. He eventually found his way to the Free City and became part of a group of displaced American soldiers there, some of whom joined the Raiders when they fled Kraków and its Machiavellian politics. As a character, Rocketman has several defining characteristics. Most obviously, he likes rockets, missiles, grenade launchers, mortars, and similar weaponry. Second, he is a good driver and always volunteers to drive one of the unit's vehicles. Finally, he's an avid reader of Dragonlance novels and makes an effort to seek out new sources of them whenever it's practical. Now that the Raiders are back in the USA, this is a fair bit easier than it was in Poland. Recently, Rocketman has begun to branch out. He's expressed an interest in Forgotten Realms novels, too, a few of which he was able to obtain in trade from soldiers stationed at Fort Lee.

On the one hand, this bit of characterization is a joke, making fun of just how many of these novels TSR published throughout the '80s and '90s – and there were a lot of them. We looked into the matter and, assuming that, in the timeline of Barrett's Raiders, TSR stopped producing new Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms novels at the end of 1997, shortly after the first Soviet nuclear strikes against America, there'd still be just shy of 100 Dragonlance novels and a little less than 80 Forgotten Realms novels. As I said, there really were a lot of these novels, but, from what I understand, they sold very, very well, outshining even the gaming material on which they were based. Talk about brandification!

On the other hand, little details like help a character to come alive. They help set him apart from his comrades and often serve as motivations for what the character does. In the case of Rocketman, he really does spend time talking to other soldiers, learning if any of them shares his interest in fantasy novels and whether there's library or other potential source for more of them. Further, his interest helps ground the campaign in its time and place. Barrett's Raiders is presently set in December 2000 in an alternate timeline that diverged at least as far back as 1985, if not earlier. Seeing as we're a quarter century removed from its chronological date and in a different reality altogether, these small reminders have proven useful.

From time to time, I should probably devote more posts to stuff like this. I've repeatedly said that the success and longevity of my various campaigns is, in large part, due to my players, who have created some really fun and memorable characters. They're one of the things that keep me engaged week after week. Shining the spotlight on some of them might prove helpful or at least interesting to readers as well.

June 17, 2025

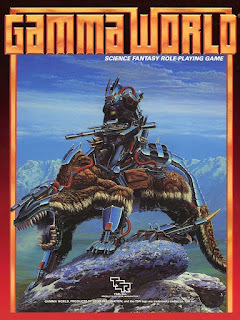

Retrospective: Gamma World (Third Edition)

A couple of years ago, I broke with tradition and penned a Retrospective post on the second edition of Gamma World, despite having already written one on the original. I justified the decision by pointing to just how different second edition was, both in tone and presentation, from its predecessor. It stood as a vivid example of how Gamma World – and roleplaying games more broadly – were evolving in the early 1980s. By that same logic, the third edition of Gamma World, released in 1986, surely warrants a post of its own, as the differences it introduced were even more pronounced.

A couple of years ago, I broke with tradition and penned a Retrospective post on the second edition of Gamma World, despite having already written one on the original. I justified the decision by pointing to just how different second edition was, both in tone and presentation, from its predecessor. It stood as a vivid example of how Gamma World – and roleplaying games more broadly – were evolving in the early 1980s. By that same logic, the third edition of Gamma World, released in 1986, surely warrants a post of its own, as the differences it introduced were even more pronounced.Since its debut in 1978, Gamma World has always seemed uncertain whether it wanted to be a madcap romp through a world of radioactive mutants or a more serious science fantasy game exploring its post-apocalyptic setting. That tension runs through every edition, but third edition feels like the first time it was intentional. I remember seeing ads for it in Dragon magazine at the time, and the cover, featuring Keith Parkinson’s vivid illustration, made a strong impression. It hinted at a bold new direction for the game, though I was struck less by its novelty than by its familiarity, having already seen the same image on a TSR calendar the year before.

If the first and second editions of Gamma World were clumsy but endearing offshoots of early D&D design – random, deadly, but bursting with imaginative potential – then the third edition marks a dramatic, and often jarring, departure. Released during a period when TSR was busy retooling many of its games in the wake of Marvel Super Heroes' success, third edition followed the lead of Star Frontiers and embraced the concept of a universal resolution system and its color-coded Action Table (ACT), column shifts, and result factors. While elegant in their original context, the ACT always felt awkward and ill-suited when retrofitted onto existing games. In Gamma World, it comes across less as a refinement and more as a mismatch – neat in theory, but clumsy in practice.

Third edition attempted to marry this new mechanical chassis to the conflicted sensibilities of earlier editions, but, in my view, the result was less than satisfactory. Combat resolution and mutation use now hinged on interpreting results from a chart – an abstraction that sapped much of the immediacy from play. Firing a Mark V Blaster was no longer a simple matter of “roll to hit, roll damage.” Instead, it became a multi-step procedure: find the appropriate ACT column, look at the result, then consult a separate chart to determine the weapon’s actual effect. One might argue this wasn’t dramatically more complex than previous systems, but for those of us who’d long ago internalized the old mechanics, it was anything but intuitive. At best, it felt like change for its own sake; at worst, a solution in search of a problem.

What also stood out – and not in a flattering way – was the presentation. The rulebook was stark and utilitarian in its layout, almost entirely bereft of artwork. What little art it did contain was mostly recycled from earlier editions, along with some lifted from Star Frontiers. A few original illustrations were scattered throughout, but they were the exception rather than the rule. Even the foldout map of Pitz Burke, a centerpiece of second edition, was repurposed here with minimal alteration. Worse still, key rules were split between the main rulebook and a separate “rules supplement” tucked into the box, fragmenting the material and giving the whole package a slapdash feel. It lacked the cohesion one expects from a fully realized edition, and instead felt cobbled together, more like a rushed repackaging than a thoughtfully constructed evolution.

Just as its mechanics felt awkwardly imposed, third edition’s treatment of the Gamma World setting also seemed diminished. Much of the evocative, if sketchy, setting material found in earlier editions was either stripped away or given only the most cursory attention. Take the cryptic alliances, for example: while they’re mentioned, their role in the world feels vague and perfunctory. Gone is the sense, so evident in second edition, that these shadowy factions were vital to understanding the post-apocalyptic landscape. The same could be said for many other aspects of Gamma World’s implied setting. It’s not that these elements are entirely absent, but that their inclusion feels scattershot and half-hearted. There’s a perfunctory, almost apathetic quality to the world-building in third edition, as if the designers were merely checking boxes rather than engaging with the material in a meaningful way. The result is a game that lacks the weird, half-glimpsed coherence that gave earlier editions their charm. It feels like a product made to fill a slot in the release schedule, not one born of creative enthusiasm.

Amidst its uneven mechanics and uninspired presentation, third edition nevertheless hinted at something more ambitious. Scattered throughout the rulebook – and more clearly in the adventure modules that followed – were the outlines of a broader campaign arc, one that seemed intended to link Gamma World to its spiritual progenitor, Metamorphosis Alpha. These modules presented ancient installations, buried technologies, and the tantalizing possibility of uncovering the true origins of the post-apocalyptic world. There were even whispers of the derelict starship Warden, as well as references to other planets and moons of the solar system, suggesting a much larger canvas than previous editions had dared to paint. That, more than anything else, remains the lasting appeal of third edition for me, the first edition to really toy with the fact that Gamma World's apocalypse belongs to the 24th century, not the 20th, and hinted at a setting far more expansive than mutant rabbits and ancient ruins.

Unfortunately, this promising thread was never fully developed. The planned module series was left incomplete and, with the arrival of Gamma World’s fourth edition in 1992, the game was rebooted once more. Any connections to Metamorphosis Alpha were quietly abandoned. Whatever larger vision might have existed was lost, leaving third edition as a curious dead end in the game’s evolution.

In the end, Gamma World Third Edition is a strange, transitional fossil, neither wholly broken nor particularly successful. It represents an attempt to modernize a legacy title by grafting onto it the mechanics of Marvel Super Heroes, but it does so without the conceptual clarity or setting depth needed to make that modernization feel purposeful. What was left is a game that is both overcomplicated and underdeveloped: a patchwork of ideas, some intriguing, others ill-suited, held together by a presentation that feels rushed and indifferent. Yet, for all its flaws, there remains a flicker of something more, an unrealized potential that somehow still has the power to capture my imagination, even if only in fragments.June 16, 2025

REPOST: The Articles of Dragon: Ares

I'm going to cheat for today's installment of this series. Rather than focusing on a single article from issue #84 of Dragon (April 1984), I'm instead going to talk about Ares, the magazine's new science fiction gaming section. First, a bit of background. Between 1980 and 1982, SPI published a gaming magazine entitled

Ares

. The magazine included a complete game in every issue (as was once typical of wargaming magazines), along with articles and reviews. Though not limited to sci-fi by any means, Ares did have a slightly science fictional bent to its content. There were eleven issues of Ares before TSR acquired SPI in 1982, followed by five more issues after the acquisition. The last stand-alone issue of Ares was published in "Winter 1983." TSR never really knew what to do with SPI's properties and wound up frittering them away over the course of the next few years, in the process alienating the company's considerable fanbase, many of whom (quite rightly) felt that TSR had handled the situation very badly. Though TSR tried to make some use of SPI's name and products, only the Ares name survived for long – and even then, "long" is a relative term.

I'm going to cheat for today's installment of this series. Rather than focusing on a single article from issue #84 of Dragon (April 1984), I'm instead going to talk about Ares, the magazine's new science fiction gaming section. First, a bit of background. Between 1980 and 1982, SPI published a gaming magazine entitled

Ares

. The magazine included a complete game in every issue (as was once typical of wargaming magazines), along with articles and reviews. Though not limited to sci-fi by any means, Ares did have a slightly science fictional bent to its content. There were eleven issues of Ares before TSR acquired SPI in 1982, followed by five more issues after the acquisition. The last stand-alone issue of Ares was published in "Winter 1983." TSR never really knew what to do with SPI's properties and wound up frittering them away over the course of the next few years, in the process alienating the company's considerable fanbase, many of whom (quite rightly) felt that TSR had handled the situation very badly. Though TSR tried to make some use of SPI's name and products, only the Ares name survived for long – and even then, "long" is a relative term.From issue #84 to issue #111 (July 1986), Ares was one of my favorite sections of Dragon, since I've always been more of a SF fan than a fantasy one. The section featured articles on games like Traveller and Star Trek and Space Opera , as well as Gamma World , Star Frontiers , and a host of superhero games, especially Marvel Super Heroes . Because sci-fi has always played second (or third) banana to fantasy, you'd have expected that the pool of articles would have been pretty shallow in Ares but that wasn't the case. In my opinion, the quality of the articles in this section was consistently high, higher even than that of the rest of Dragon (which is saying something). However, its appeal was definitely more limited, which is why I suspect it was eventually killed. Why devote some many pages of each issue to genres that are also-rans compared to fantasy, especially D&D's brand of fantasy?

To this day, though, when I look back on the years when I subscribed to Dragon, the Ares articles are among those that stick out most prominently in my mind. Its coverage of Gamma World, for example, was truly excellent and I used a number of its Traveller rules variants over the years. And of course Jeff Grubb's regular "The Marvel-Phile" column was invaluable if you were running a Marvel Super Heroes campaign (or even if you weren't and were just a fan of the comics). I've always thought it a pity that a non-fantasy-centric gaming mag never really gained any degree of prominence. GDW's Challenge, where my first published writings appeared, was a decent stab at such a thing, but it eventually folded, too, much to my disappointment. Like Ares, Challenge filled a hole in the hobby that needed filling. In my opinion, it still does.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers