James Maliszewski's Blog, page 125

December 6, 2021

Regrets of a TSR Fanboy

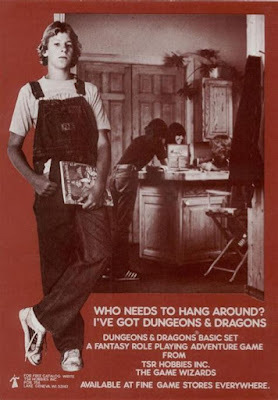

Like the vast majority of gamers my age, TSR's Dungeons & Dragons was my gateway into the hobby of roleplaying. There's nothing remarkable in this. By the time I first encountered it in late 1979, D&D was already the proverbial 800-lb. gorilla of RPGs and its boxed sets, books, and adventure modules could be found quite widely Equally available were TSR's other offerings, such as Gamma World and

Top Secret

, the former of which became a near-rival to D&D in my affections for a time.

Like the vast majority of gamers my age, TSR's Dungeons & Dragons was my gateway into the hobby of roleplaying. There's nothing remarkable in this. By the time I first encountered it in late 1979, D&D was already the proverbial 800-lb. gorilla of RPGs and its boxed sets, books, and adventure modules could be found quite widely Equally available were TSR's other offerings, such as Gamma World and

Top Secret

, the former of which became a near-rival to D&D in my affections for a time. Later, I would discover and subscribe to Dragon magazine and even joined the RPGA, though mostly to gain access to its often excellent Polyhedron newszine. In the pre-Internet age, these periodicals were one of the few ways – aside from idle chats in game stores – that I could easily learn about the wider hobby. Dragon in particular did a good job at this, exposing me to news and advertisements of which I might otherwise have been unaware. Of course, some of the news and much of the editorial content had a decidedly TSR-centric slant to it and that colored my view of the hobby for a very long time.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I became very devoted to TSR and its games, most of which I dutifully bought and played as soon as they were published. Certainly, I played games from other companies, particularly those of GDW (about which I rhapsodize regularly on this blog), but it was TSR to which I owed my true allegiance. I hung on every word that flowed from the pen of Gary Gygax and can now sheepishly recall my ability to quote many of his jeremiads as if they were my own. I had found a "team" to root for and a celebrity to look up to in TSR and Gygax.

Now, there's nothing inherently wrong in this. I suspect that many boys in their tween and early teen years go through a phase of this sort, before eventually growing out of it. That was the case with me, though it took me a little longer to emerge from it than many (and some readers might well doubt that I've ever succeeded in doing so). From the vantage point of middle age, it's all a bit embarrassing, of course, but no more so than many other foolish or ill considered things I've done over the course of my half century of existence. Yet, there's still one aspect of my puerile obsession with TSR that I do genuinely regret – and that's the unwillingness it engendered in me to play RPGs by other publishers.

I did play a small selection of non-TSR games, most notably Traveller and Call of Cthulhu. In each case, I did so in part because of my prior fondness for their literary inspirations (as well as the recommendations of older gamers whose opinions I respected). Beyond those two – and FASA's Star Trek – I generally avoided RPGs by other publishers. I dabbled from time to time, even occasionally falling into brief but ultimately fruitless love affairs with the odd game here or there, but, by and large, I stuck with TSR to the point of closing off other possibilities I might genuinely have enjoyed.

This is particularly true with regards to Chaosium. Though I was an avid devotee of Call of Cthulhu, I nevertheless eschewed the company's other games. There was no good reason for this beyond an irrational sense that I owed loyalty to TSR and its games. Somehow, in my head, I saw the purchase and play of RPGs as a zero sum game rather than as an immense feast with almost infinite variety from which I could pick and choose to my heart's content. It's an odd quirk of my personality and, while I have, in the decades since, much expanded my horizons with regards to roleplaying games, I still occasionally feel pangs of regret about my adolescent closemindedness.

Live and learn!

December 5, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Fire of Asshurbanipal

When it comes to "pulp fantasy," few can compare to Robert E. Howard. Between the characters of Conan, Kull, Bran Mak Morn, and Solomon Kane, Howard more or less established the pattern that later writers would, to varying degrees of success, follow and that would, in the process, serve as a seedbed out of which Dungeons & Dragons and other fantasy RPGs would spring. Nevertheless, it's important to remember that Howard was a truly industrious writer, penning more than four hundred stories (and even more poems) in a little over a decade of professional writing. While the stories of Conan and Kane understandably loom large today, as they did during REH's lifetime, he wrote many more, many of which ought to be of interest to fantasy fans and roleplayers alike.

When it comes to "pulp fantasy," few can compare to Robert E. Howard. Between the characters of Conan, Kull, Bran Mak Morn, and Solomon Kane, Howard more or less established the pattern that later writers would, to varying degrees of success, follow and that would, in the process, serve as a seedbed out of which Dungeons & Dragons and other fantasy RPGs would spring. Nevertheless, it's important to remember that Howard was a truly industrious writer, penning more than four hundred stories (and even more poems) in a little over a decade of professional writing. While the stories of Conan and Kane understandably loom large today, as they did during REH's lifetime, he wrote many more, many of which ought to be of interest to fantasy fans and roleplayers alike.

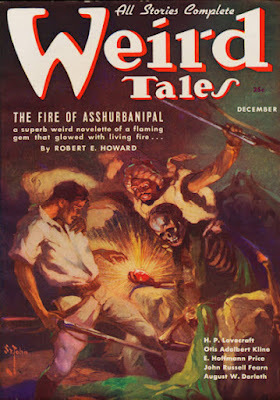

Take, for example, "The Fire of Asshurbanipal," which appeared in the December 1937 issue of Weird Tales. Astute readers will immediately notice that this date is after Howard's death in June 1936. "Fire" is one of three stories sent to Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright by Isaac Howard, Robert's father. Wright immediately recognized the value in being able to present original REH yarns to a readership still reeling from his death the year before. He even went so far as to give "Fire" the cover illustration – a formerly common occurrence for Howard, whose stories were regularly among the most well regarded in the pages of the Unique Magazine.

"The Fire of Asshurbanipal" doesn't take place in a mythical past or even centuries ago. While the precise date of its action is unclear, it's likely sometime in the first decades of the 20th century, based on a couple of offhand references to things like the Lee-Enfield repeating rifle. Ultimately, its precise date is unimportant, as all the story's events take place in and around Central Asia, or Turkestan, as Howard calls it. Two-fisted American adventurer Steve Clarney and his Afghan friend Yar Ali are on the trail of a fabulous red gem, the titular Fire of Asshurbanipal. The pair had learned from a dying Turk that the gem was located in "a silent dead city of black stone set in the drifting sands" and could be found "clutched in the bony fingers of a skeleton on an ancient throne." Later investigation reveals that the city in question was

the ancient City of Evil spoken of in the Necronomicon of the mad Alhazred – the city of the dead on which an ancient curse rested. And the gem was an ancient and accursed jewel belonging to a king of long ago whom the Grecians called Sardanapalus and the Semitic peoples Asshurbanipal.

Lost cities in the sand and cursed gems are a dime a dozen in pulp stories, you might say and you'd be correct. What sets this tale apart is its reference to Lovecraft's Necronomicon and its author. This isn't a mere throwaway line, a bit of fan service for devotees of HPL's evolving Cthulhu Mythos. No, it's an early indication that there's more going on in this story than a rollicking adventure after the fashion of H. Rider Haggard. More than that, it's an indication that we're going to read Robert E. Howard's take on the concepts and themes of Lovecraft, which, to my mind, is pretty exciting. Later in the story, when Clarney and Ali are exploring the buried city they were seeking, we get an idea of just what I mean by this.

"Allaho akbar!" They had traversed the greatb shadowy hall and at its further end they came upon a hideous black stone altar, behind which loomed an ancient god, bestial and horrific. Steve shrugged his shoulders as he recognized the monstrous aspect of the image – aye, that was Baal, on whose black altar in other ages many a screaming, writhing naked victim had offered up the quivering soul. The idol embodied in its utter, abysmal and sullen bestiality the whole soul of this demoniac city. Surely, thought Steve, the builders of Nineveh and Kara-Shehr were cast in another mold than the people of today. Their art and their culture were too ponderous, too grimly barren of the lighter aspects of humanity, to be wholly human. Their architecture was of the highest skill, yet of a massive, sullen and brutish nature beyond the ken of modern man.

Lovecraft's tales often feature musings about the alien nature of the otherworldly beings who built some structure upon the earth or were engaged in some activity. The elder things of "At the Mountains of Madness," are a good example of this, as are the Mi-go of "The Whisperer in Darkness." Rather than ape the approach of his friend and correspondent, Howard instead muses about how alien the men of the past seem from the perspective of today – their art, culture, and architecture are impressive, yet also "barren of the lighter aspects of humanity" to the point that they can't even be called "wholly human." It's an interesting approach, I think, and one that surely differs from that of Lovecraft. Even if one does not agree with Howard's take on the matter, I don't think there can be any question that he's attempting something genuinely different, which is commendable.

All that said, make no mistake: "The Fire of Asshurbanipal" remains a rousing pulp story, in which Howard's protagonists not only find an ancient city buried in the sand and the treasure it holds, but also face off against enemies both human and inhuman. In many ways, it reads like a rather fun Call of Cthulhu scenario set in Central Asia, but with plenty of uniquely Howardian touches that it doesn't come across as a mere pastiche of Lovecraft's own work. It's not as well known a story as it should be and I recommend seeking out.

November 30, 2021

Retrospective: Mayday

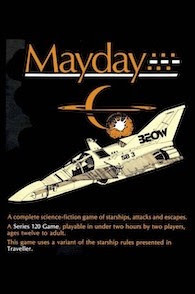

These days, I find myself missing the late, great Game Designers' Workshop a lot. Maybe it's the recent release of a new edition of Twilight: 2000 by Free League or maybe it's just another manifestation of midlife melancholy. Whatever it is, I've spent much time over the past few weeks poring over GDW's impressive output, not least of which being its many fine Traveller products.

These days, I find myself missing the late, great Game Designers' Workshop a lot. Maybe it's the recent release of a new edition of Twilight: 2000 by Free League or maybe it's just another manifestation of midlife melancholy. Whatever it is, I've spent much time over the past few weeks poring over GDW's impressive output, not least of which being its many fine Traveller products. As I never tire of saying, Dungeons & Dragons may be my first love, but Traveller is my true love. No matter how many years pass, my admiration for it remains stronger. If anything, it's only gotten stronger with the years, as I came to appreciate better many aspects of its design. One of those aspects is its modularity, something I've commented on before. Though Trtaveller is a complete science fiction roleplaying game, its three constituent books contain numerous systems and sub-systems that could very easily be games in themselves – and, in a few cases, were presented as such.

Mayday is an example of this. Originally published in 1978, a year after the initial release of Traveller, Mayday takes the RPG's starship combat system and turns it into a two-player wargame playable in, at most, a couple of hours. The original edition came in a ziplock bag, like the other "Series 120" games released by GDW (so called because they could be played in 120 minutes or less), but later editions came in boxes, a digest-sized one in 1980 and an 8½" × 11" one in 1983. In my youth, I owned the 1983 edition but, like so many of my older games, it fell apart and I replaced it with the 1980 edition I still own to this day.

The contents of the box are few: a 16-page rulebook, a sheet of cardboard counters, a single six-sider, and a handful of blank black-and-white hex maps. Anyone already familiar with Traveller's starship rules will find little surprising here, but newcomers might be surprised by several aspects of it. For example, each turn represents 100 minutes of time and each hex represents 300,000 km or one light-second. This is not a game of fast and furious tactical dogfighting of the sort one sees in science fiction cinema, but rather of slow, almost strategic combat over large distances. This, of course suits the style of SF that inspired Traveller, but it might take some getting used to if you're not well versed in the classics of older science fiction literature.

Another noteworthy aspect of Mayday – and indeed of Traveller starship combat in general – is its use of vector movement. The distance and direction a ship moves during its turn is based on the distance and direction moved in its previous turn. This means that even vessels with high acceleration ratings cannot simply turn on a dime but must slow themselves before being able to change course. This whole process is further affected by the presence of gravity fields from massive objects like planets. The end result is a game where mastering the movement system is even more important than mastering its weapons rules. It's very fun but I must confess that it took me a long time to wrap my head around how it worked. Even now, it still takes me a while to get into the proper frame of mind to play it.

That's a good thing in my opinion and one of the reasons why Mayday, much like Traveller, continues to appeal to me. Unlike other starship combat games, which, while fun, are little more than diversions, Mayday also manages to be thought-provoking. I don't mean that it makes me think deep thoughts about life, the universe, and everything, but rather that it demands I pay careful attention to the all the starships' vectors in relation to one another. I won't go so far as to claim this is a "thinking man's starship combat game," but there's little question in my mind that Mayday demands some brainpower to play enjoyably, never mind successfully.

I really do miss GDW.

White Dwarf: Issue #18

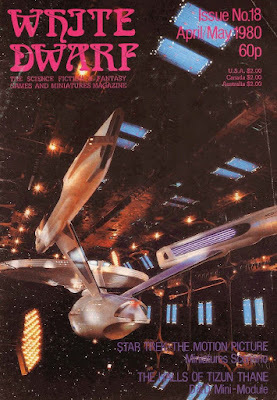

Issue #18 of White Dwarf (April/May 1980) features an unusual cover image: a color still of the starship Enterprise from Star Trek: The Motion Picture. That's a particularly potent image for me, since I was a huge fan of Star Trek as a kid and, unlike many people my age, I absolutely loved The Motion Picture. I nevertheless find it strange to see this on the cover of WD, which I have long associated with less "mainstream" depictions of fantasy and science fiction subjects. All that aside, the cover at least has some relevance to the content of the issue. The very first article, entitled simply "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" is a set of miniatures rules for use with Citadel's officially licensed Star Trek minis. Written by Tony Yates and Steve Jackson (the British one, of course), the rules are brief, focusing largely on combat, though there are mechanical nods to other activities. The article also includes statistics for the named characters of Trek (Kirk, Spock, McCoy, etc.) and a variety of alien species, as well as a scenario with a map.

Issue #18 of White Dwarf (April/May 1980) features an unusual cover image: a color still of the starship Enterprise from Star Trek: The Motion Picture. That's a particularly potent image for me, since I was a huge fan of Star Trek as a kid and, unlike many people my age, I absolutely loved The Motion Picture. I nevertheless find it strange to see this on the cover of WD, which I have long associated with less "mainstream" depictions of fantasy and science fiction subjects. All that aside, the cover at least has some relevance to the content of the issue. The very first article, entitled simply "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" is a set of miniatures rules for use with Citadel's officially licensed Star Trek minis. Written by Tony Yates and Steve Jackson (the British one, of course), the rules are brief, focusing largely on combat, though there are mechanical nods to other activities. The article also includes statistics for the named characters of Trek (Kirk, Spock, McCoy, etc.) and a variety of alien species, as well as a scenario with a map. "Open Box" reviews three products, only one of which I have any familiarity. The first is Eon's Darkover boardgame based on the novels by Marion Zimmer Bradley. The review is quite lengthy for "Open Box" – slightly over a full page in length – and quite effusive (9 out of 10). The second, for Task Force's Swordquest, a fantasy boardgame, is more middling in its assessment (6 out of 10). The final review is Dra'k'ne Station, a Traveller adventure published by Judges Guild. The reviewer, Bob McWilliams, a name I strongly associate with excellent Traveller articles in White Dwarf, is quite impressed with the product (8 out of 10), which I suppose I can understand, given how comparatively little Traveller product existed by this time. For myself, I'm generally not all that impressed with most of Judges Guild's Traveller materials, including this one.

The centerpiece of the issue is Albie Fiore's The Halls of Tizun Thane about which I wrote a post at the start of this year. I don't have much to add to my comments from January, except to reiterate at how impressive the adventure is in terms of size and scope. The titular halls consist of more than sixty keyed rooms and there are a large number of NPCs (not to mention two new monsters) with which to interact. Adventures like this were a hallmark of White Dwarf as I remember it and I look forward to seeing more of them in the future.

"Treasure Tables" presents a number of different random tables, from a frankly bizarre one for "accurately" determining the handedness of a NPC to ones for generating weather patterns. I love tables as much as the next guy, but it's vital that they be useful and well made. Most of these are, sadly, are not. "The Fiend Factory" includes four new monsters, one of which is the couerl, a variation on the displacer beast, which is itself a ripoff of A.E. van Vogt's original couerl – a classic example of pop cultural recursion. "The Magic Brush" by Shawn Fuller is a lengthy treatment of the basic techniques of painting miniatures and seems (to a non-painter) to be quite well done. I've long admired those with the skills to paint miniatures attractively, so articles like this hold my attention despite my own lack of direct experience in the area.

All in all, issue #18 of White Dwarf is a fairly mixed bag, as one might expect from almost any periodical. The high point is definitely Albie Fiore's adventure, which I hope heralds similarly excellent content in future issues.

November 28, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Death of Ilalotha

Since last week's Pulp Fantasy Library post concerned a Zothique pastiche by Gene Wolfe, it seemed only right that I should follow it up with a discussion of one of Clark Ashton Smith's own tales of the Last Continent, in this case "The Death of Ilalotha," which first appeared in the September 1937 issue of Weird Tales. The story is one of which Smith was himself quite fond, calling it a "somewhat poisonous little horror" in a letter to August Derleth. Despite this, he apparently had difficulty selling it to Weird Tales. The magazine's editor, Farnsworth Wright, claimed "there is no story here" and returned it to Smith, who then reworked it to give it a stronger narrative. Smith's revisions not only met with Wright's approval but with the readership of Weird Tales, who voted it the best story of the issue. (As an aside, the September 1937 issue is notorious for its Margaret Brundage cover, which landed it in hot water with censors in Philadelphia at the time of its publication.)

Since last week's Pulp Fantasy Library post concerned a Zothique pastiche by Gene Wolfe, it seemed only right that I should follow it up with a discussion of one of Clark Ashton Smith's own tales of the Last Continent, in this case "The Death of Ilalotha," which first appeared in the September 1937 issue of Weird Tales. The story is one of which Smith was himself quite fond, calling it a "somewhat poisonous little horror" in a letter to August Derleth. Despite this, he apparently had difficulty selling it to Weird Tales. The magazine's editor, Farnsworth Wright, claimed "there is no story here" and returned it to Smith, who then reworked it to give it a stronger narrative. Smith's revisions not only met with Wright's approval but with the readership of Weird Tales, who voted it the best story of the issue. (As an aside, the September 1937 issue is notorious for its Margaret Brundage cover, which landed it in hot water with censors in Philadelphia at the time of its publication.)Loath though I am to agree with the dread satrap Pharnabazus – one of H.P. Lovecraft's satirical nicknames for Wright – I can't deny that "The Death of Ilalotha" is very weak as a story, especially when compared to many of Smith's more celebrated efforts. It's still an enjoyable read, both for its unparalleled use of language and the mood it conjures, but one should not expect to be wholly satisfied with its plot, which remains quite weak. Rather than a "story," I might instead call "The Death of Ilalotha" a "situation" – and an unnerving one at that.

The piece begins with the funeral observance of the titular Ilalotha, whom we learn was a lady-in-waiting to "the self-widowed" Queen Xantlicha of Tasuun. According to the customs of Tasuun, funerals lasted several days and were the "occasion for much merrymaking and prolonged festivity."

For three days, on a bier of diverse-colored silks from the Orient, under a rose-hued canopy that might well have domed some nuptial couch, she had lain clad with gala garments amid the great feasting-hall of the royal palace in Miraab. About her, from morning dusk to sunset, from cool even to torridly glaring dawn, the feverish tide of the funeral orgies had surged and eddied without slackening. Nobles, court officials, guardsmen, scullions, astrologers, eunuchs, and all the high ladies, waiting women and female slaves of Xantlicha, had taken part in that prodigal debauchery which was believed to honor most fitly the deceased.

Only Clark Ashton Smith could write the phrase "funeral orgies" without its seeming laughable. From his pen, it seems not only natural but fitting, especially in light of the morbid melancholy of Zothique. In the midst of describing the licentious festivities, CAS takes a moment to comment on the deceased.

With half-shut eyes and lips slightly parted, in the rosy shadow cast by the catafalque, she wore no aspect of death but seemed a sleeping empress who ruled impartially over the living and the dead. This appearance, together with a strange heightening of her natural beauty, was remarked by many; and some said that she seemed to await a lover's kiss rather than the kisses of the worm.

I trust no one will be surprised to learn that these comments are not idle ones.

We soon discover that also present is Lord Thulos, "acknowledged lover of Queen Xantlicha," who had been away and only just arrived. He was thus unaware of the nature of the festivities. Prior to his having taken up with the queen, Ilalotha had been the paramour of Thulos and, "it was said, had grieved more passionately over his defection than any other."

Thulos, perhaps, had abandoned her not without regret: for the role of lover to the queen, though advantageous and not wholly disagreeable, was somewhat precarious. Xantlicha, it was universally believed, had rid herself of the late King Archain by means of a tomb-discovered vial of poison that owed its peculiar subtlety and virulence to the art of the ancient sorcerers. Following this act of disposal, she had taken many lovers, and those who failed to please her came invariably to ends no less violent than that of Archain.

Seeing his obvious sadness upon viewing Ilalotha's dead body, Queen Xantlicha approaches Thulos and warns him that "men say she was a witch." He cannot believe this, for he knew her well. Xantlicha continues to assert the truth of her charge, adding that Ilalotha had died "from no other fever than that of love."

"It was from love of thee," said Xantlicha darkly; "and, as all women know, thy heart is blacker and harder than black adamant. No witchcraft, however potent, could prevail thereon." Her mood, as she spoke. appeared to soften suddenly. "Thy absence has been long, my lord. Come to me at midnight: I will wait for thee in the south pavilion."

With the queen gone, Thulos turns his attention once again to Ilalotha. He then begins to imagine that she is not dead, that she has just kissed him, and that she calls to him with outstretched arms. "Come to me at midnight. I will await for thee … in the tomb," he hears her say. Though Thulos doubts what he has just imagined, he cannot be certain that it was a mere hallucination. What if the queen is right and Ilalotha was a witch. If so, she would surely have found a way to escape even death. He had to find out, even if it meant failing to keep his assignation with Xantlicha at the same time.

"The Death of Ilalotha" is a "poisonous little horror," as Smith described it, full of creeping dread and intimations of doom, not to mention luxurious language. The narrative itself is slight but I doubt anyone will mind, given its brevity. One reads Clark Ashton Smith for his ability to set a scene and induce unsettling – yet somehow still pleasurable – feelings in his readers. "The Death of Ilalotha" easily delivers that and more.

November 21, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: A Traveler in Desert Lands

As a general rule, I tend to be skeptical of the efforts of writers who take it upon themselves to play in someone else's playground. Heck, I'm similarly skeptical about the efforts of writers who return to their own playgrounds many years after the fact. The results in both cases are rarely good in my opinion, which is why I tend to avoid them. Nevertheless, I occasionally make exceptions, usually because I'd either heard something positive beforehand or because I allowed my own enthusiasm get the better of them. The Last Continent: New Tales of Zothique is an example of the latter.

As a general rule, I tend to be skeptical of the efforts of writers who take it upon themselves to play in someone else's playground. Heck, I'm similarly skeptical about the efforts of writers who return to their own playgrounds many years after the fact. The results in both cases are rarely good in my opinion, which is why I tend to avoid them. Nevertheless, I occasionally make exceptions, usually because I'd either heard something positive beforehand or because I allowed my own enthusiasm get the better of them. The Last Continent: New Tales of Zothique is an example of the latter.Edited by John Pelan and published in 1999, The Last Continent is an anthology of original stories set in Clark Ashton Smith's setting of Zothique. Now, Zothique is a favorite of mine. Of all of Smith's creations, it's the one I most enjoy – which is saying something. Consequently, when I heard about this collection, I quickly snapped it up, hoping I'd find at least one new Zonthique story worthy of the Bard of Auburn himself.

As it happened, I found several, but the one I most recall, years later, is "A Traveler in Desert" lands by Gene Wolfe. Wolfe is, of course, the celebrated author of The Shadow of the Torturer and the other volumes of The Book of the New Sun, so his byline on a short story set in Zothique is not entirely surprising. The world of Severian is a kind of far future "dying earth" with some similarities to Zothique and Wolfe's command of archaic and esoteric vocabulary is every bit as hypnotic as that of CAS. That said, "A Traveler in Desert Lands" contains little that explicitly links it to Zothique beyond its mellifluous style and morbid subject matter. Perhaps that's why I enjoyed it as much as I do; unlike some of the other stories in this collection, it doesn't read like someone's Clark Ashton Smith fan fiction but rather a wholly original homage to his works.

The titular traveler is making his way across a desert on the back of a camel. Tired and thirsty, he stops "in the soft and shifting dust of the lost town of the dead" where he spies a very slender woman walking with a water jar upon her head. Courteously, he asks her if he might take some water from her.

"You would honor me by drinking," the woman with the jar said, "and by filling whatever skins and bottles you may have. If you empty my jar," her face convulsed as if to dislodge some brass-backed carrion fly that none but she could see, "it is a matter of no moment, for I can easily refill it at our well."Though this surprises the traveler – he did not expect to find water so readily in the desert – he is very grateful. He takes a drink of water to slake his thirst and then asks where the well is, so that he might fill all his canteens and water his camel before moving on.

The woman does not respond; instead, she simply walks away. The traveler and his camel follow her into the nearby town and its "bleak streets of tombs."

Some remained sealed – or so it appeared. Others had clearly been broken into, looted, and abandoned. Still others gave evidence of habitation; and at the door of one he saw an old man seated, his dusty cheeks streaked with tears and his raddled face stamped with grief. The woman with the water jar halted to speak to this old man, though the traveler could not hear what she said; the old man nodded in response, his face perhaps a trifle less hopeless than it had been.

As he continued to follow the slender woman, hoping she was leading him to the well of which she had spoken, his mind wanders. He thinks about the tombs he sees everywhere and what they imply.

Where there were tombs and men who robbed them, there might be silver and gold besides, necklaces and emeralds and torques starry with opals. The thought revived him more, even, than the water had – for the traveler had been born of woman and suckled at the breast, and like all the breed was in need of money.

I smiled when I first read these sentences, as they struck as being not only true to so many of Smith's venal protagonists but also to the player characters one encounters in many a fantasy roleplaying game campaign. In any case, the woman does eventually lead him to the the well, located underground and accessible by a set of stone steps. She tells the traveler to leave his camel behind and to descend into the depths with her.

He agrees and fills canteens to capacity. He also takes up water for his camel, a process that, even while aided by the woman, takes some time. Before long, the night is beginning to fall. This leads the woman to ask him, "Will you stay in our town tonight?" Again, the traveler agrees, hoping that, in addition to rest, he might be able to buy or trade for provisions from the inhabitants of this strange settlement. The woman assures him her people can provide him with goat's meat, cheese, and vegetables – but only in the morning. The traveler accepts this and prepares to settle in for the night.

This being a pulp fantasy story – and one after the fashion of Clark Ashton Smith, no less – things are not what they appear to be, as the traveler soon learns. What separates "A Traveler in Desert Lands" from other stories of this kind is not so much its revelations as the overall mood of the piece. Wolfe does a superb job of slowly building tension through the accumulation of small details and hints. His description of the town where the woman and her family live is a good example of this, as the reader slowly comes to realize that they actually live inside of a looted mausoleum. "Town of the dead" is not a metaphor; this is no ghost town in the conventional sense. Rather, it is an ancient cemetery whose tombs have now become the dwelling places of later inhabitants. It's wonderfully macabre and exactly the kind of thing I'd expect to find in a good tale of Zothique. That I found it in a Zothique tale not written by Smith is all the more remarkable – but then Gene Wolfe is no ordinary writer.

November 18, 2021

White Dwarf Interviews Greg Stafford

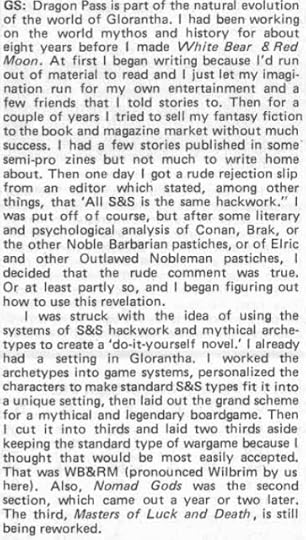

As I mentioned in my recent post about issue #17 of White Dwarf, the issue contains a fascinating interview with Greg Stafford, creator of the fantasy setting of Glorantha and a founder of Chaosium. The interview was apparently conducted at GenCon XII (1979) by Ian Livingstone and covers a wide range of topics, with special attention paid to Stafford's thoughts about Glorantha, RuneQuest, and roleplaying in general. From the vantage point of 2021, I find the interview remarkable, not just for the topics it covers but for the answers Stafford gives, some of which are truly unique.

Livingstone begins by asking about the origins of Glorantha – or "the world of Dragon Pass," as he calls it throughout the interview – and Stafford replies at length:

There's a lot to unpack here, starting with the fact that Glorantha begin, much like M.A.R. Barker's Tékumel, as something Stafford created "for [his] own entertainment." More interesting is his partial agreement with the rude editor who claimed that "All S&S is the same hackwork." I hear variations of this claim a lot, particularly from those who dislike this blog's focus on the pulp fantasy antecedents of D&D and other early RPGs. Consequently, I was initially taken aback by Stafford's seeming acceptance of it, if only partially. However, as he seems to suggest in the second paragraph of his response, he recognizes the value of "standard S&S types."

Stafford explains a bit about his own literary education, including the authors and stories that most influenced him.

None of what he says here surprises me, though why he singles out Vathek for opprobrium I can't be sure. More notable, I think, is that Stafford elevates Joseph Campbell, Mircea Eliade, Sir James Frazer, and Bob Dylan(!) to the same level as Tolkien and Homer in terms of influence upon him. That says a great deal about what Stafford hoped to achieve through the development of Glorantha. It also explains why I was frequently told, in my early days, that RuneQuest was "a hippy game" to be avoided by good East Coast boys like myself.

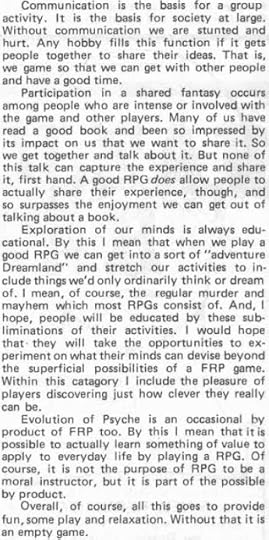

None of what he says here surprises me, though why he singles out Vathek for opprobrium I can't be sure. More notable, I think, is that Stafford elevates Joseph Campbell, Mircea Eliade, Sir James Frazer, and Bob Dylan(!) to the same level as Tolkien and Homer in terms of influence upon him. That says a great deal about what Stafford hoped to achieve through the development of Glorantha. It also explains why I was frequently told, in my early days, that RuneQuest was "a hippy game" to be avoided by good East Coast boys like myself.Interesting though all this is, the real meat of the interview comes when Livingstone asks Stafford about his thoughts on the popularity of RPGs. Stafford replies that he believes this popularity rests on four elements: "1. Communication with others; 2. Participation in a shared fantasy; 3. Exploration of our minds; 4. Exploration of the psyche." He expands upon each of these shortly thereafter:

A whole series of posts could no doubt be written teasing out the implications of everything Stafford says here. Perhaps one day I'll do just that. For the moment, though, I think it suffices to say that Stafford definitely has some genuine insight here into the appeal of roleplaying games. In particular, I think his comments about "shared fantasy" are spot on, at least as far as my own feelings are concerned.

A whole series of posts could no doubt be written teasing out the implications of everything Stafford says here. Perhaps one day I'll do just that. For the moment, though, I think it suffices to say that Stafford definitely has some genuine insight here into the appeal of roleplaying games. In particular, I think his comments about "shared fantasy" are spot on, at least as far as my own feelings are concerned. Later, Stafford returns to some of these same topics, when he offers his opinions on the future of the RPG hobby and what purposes roleplaying games might serve in the future.

I remember the late 1970s quite well; there was definitely a pessimism about the future in the air, much as there is in many quarters nowadays. That Stafford saw RPGs as a lifeline in difficult times is worth bearing in mind, regardless of whether one shares his gloominess. I can certainly say that I greatly value the games I play each week with my friends across the globe. The connection they provided during the last couple of years has been vital and I doubt I am alone in feeling that.

I remember the late 1970s quite well; there was definitely a pessimism about the future in the air, much as there is in many quarters nowadays. That Stafford saw RPGs as a lifeline in difficult times is worth bearing in mind, regardless of whether one shares his gloominess. I can certainly say that I greatly value the games I play each week with my friends across the globe. The connection they provided during the last couple of years has been vital and I doubt I am alone in feeling that.

November 17, 2021

Retrospective: Telengard

I didn't own a computer until I was well into the start of my third decade of life. Nevertheless, from my elementary school days on, I had ready access to them, thanks to friends and classmates whose families were more technophilic than my own. For example, my best friend in the latter years of grade school (and who shared my love of D&D) owned a TRS-80 on which I spent endless hours playing a primitive Star Trek game. Similarly, a high school buddy of mine had an Apple IIc, making it possible for me to play Wizardry. So, while I didn't have a computer of my own, I was quite familiar with many of the primitive models available in my youth and used them when I was able.

I didn't own a computer until I was well into the start of my third decade of life. Nevertheless, from my elementary school days on, I had ready access to them, thanks to friends and classmates whose families were more technophilic than my own. For example, my best friend in the latter years of grade school (and who shared my love of D&D) owned a TRS-80 on which I spent endless hours playing a primitive Star Trek game. Similarly, a high school buddy of mine had an Apple IIc, making it possible for me to play Wizardry. So, while I didn't have a computer of my own, I was quite familiar with many of the primitive models available in my youth and used them when I was able.Of all these, the one I remember most is the Atari 400 8-bit computer. A neighborhood friend, whose older brother was a gaming mentor, owned one – or, rather, his father did – and our little circle of boys used to gather round it in his living room to goggle at this marvel of modern technology. We also played games, as we were able, most of them quite forgettable. Of course, we didn't care at the time. The mere existence of a computer game was usually enough to hold our attention, resulting in a lot of wasted time.

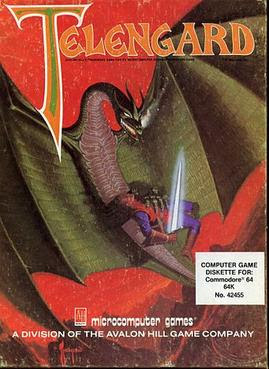

Looking back on those days, one game continues to stand out in my memory as being better than the rest: Telengard, released by Avalon Hill in 1982. Telengard was what would nowadays be called a "dungeon crawler" in that the focus of play was navigating one's randomly generated character through an immense, 50-level dungeon filled with all manner of monsters, traps, and treasures. Like most computer games of that era, it was exceedingly limited, both in terms of options and presentation, but that didn't matter. To a thirteen year-old in the early '80s, Telengard was unbelievably cool – and about as close as you could get to digitizing the experience of playing Dungeons & Dragons.

That's because Telengard pretty much was D&D. I'm honestly surprised that TSR didn't sue or at least legally threaten Avalon Hill over the game. Characters in the game had the exact same ability scores as in D&D and the purpose of the game was to amass experience points through defeating monsters and finding treasure, thereby achieving higher levels of power, just like D&D. The selection of monsters (36 in all) included a number obviously derived from D&D, such as the gnoll and experience point-draining wraiths and spectres. Spells and magic items were likewise derivative of Gygax and Arneson's creation, with elven cloaks and boots, magic missile, and cure light wounds available, among others. As I said, I'm startled that TSR let this slide.

The primary difference between Telengard and D&D is that the computer game had no character classes. Instead, every character was equally adept at casting spells and engaging in combat. Spellcasting was handled through the use of a spell point (or "spell unit") system, but was otherwise reminiscent of the way D&D handled magic. Interestingly, turn undead was a spell; indeed, the spell list is a mixture of those available to clerics and magic-users in D&D. This gave your character a bit more versatility than in D&D, but that's understandable as Telengard provided neither an option for multiplayer nor for the acquisition of henchmen. Instead, your character was left to his own devices in facing off against the dangers of the dungeon.

To call Telengard unforgiving is an understatement. Not only were the contents of dungeon rooms random (though, like D&D, scaled to level), the entire game was played in real time. In fact, the game manual, as I recall, takes great pains to point this out to the player. There are no safe areas except outside the dungeon itself. Further, you cannot save your progress within the dungeon. The combination of these factors meant that caution was advisable, just as in D&D. Of course, the computer was even more merciless than a living referee; no amount of whining or wheedling could convince it to keep your character alive after a foolhardy decision or a bad throw of the virtual dice.

And yet, we loved it. Some of that love was no doubt a function of neopohilia. The very idea of playing a fantasy game on a computer was simply so captivating in itself that we didn't care how hard it was to survive. At the same time, I also think that its difficulty appealed to our competitive instincts and desire for genuine challenge. Being able to escape the dungeon with enough gold to gain a new level felt like a genuine accomplishment, especially when we knew just how easy it was to turn the wrong corner and run into a dragon or a vampire, not to mention a teleporter trap that sent us to some unknown lower level. The very unfairness of Telengard was part of its attraction, I think – but then the minds of teenage boys are strange things.

I don't know that I'd enjoy Telengard or a game like it anymore. At the time, though, it was genuinely engrossing and I can still remember how much fun we all had facing off against the program. There are days when I wish I could have these kinds of experiences again.

November 16, 2021

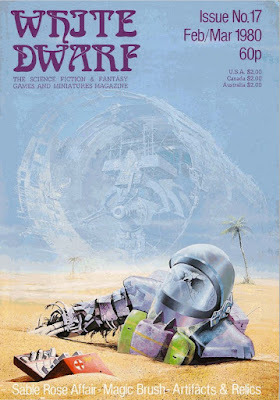

White Dwarf: Issue #17

Issue #17 of White Dwarf (February/March 1980) features a science fictional cover by Angus McKie. In my memory, one of the things that distinguished White Dwarf from, say, Dragon is that the former frequently boasted cover art that drew from SF or that mixed sci-fi with fantasy. As a huge fan of the genre, this always pleased me.

Issue #17 of White Dwarf (February/March 1980) features a science fictional cover by Angus McKie. In my memory, one of the things that distinguished White Dwarf from, say, Dragon is that the former frequently boasted cover art that drew from SF or that mixed sci-fi with fantasy. As a huge fan of the genre, this always pleased me. The issue begins with an interesting editorial by Ian Livingstone, in which he talks about the perceived expense of a roleplaying game versus a more traditional boardgame. "Is this all I get?" he imagines a newcomer to the hobby saying upon opening his D&D Basic Set. Livingstone then suggests that, because RPGs are a niche hobby, they'll always be more expensive than their mainstream counterparts. The only way that will change is if roleplaying games were to appeal to a wide enough audience that mass market factors enter the equation. For that to occur, he opines, RPGs "would have to be modified out of all recognition and lose their appeal." I'm not sure that history has proven Livingstone wrong.

"The Fiend Factory" offers up six more monsters in this issue. Perhaps I am unusual in this respect, but I'm tiring of the "The Fiend Factory." I'd much rather see clever ways to use existing monsters – of which D&D already had an immensity in 1980 – than an endless menagerie of new ones. "Open Box" is mostly given over to Judges Guild product reviews, starting with Under the Storm Giant's Castle (5 out of 10) and Dark Tower (9 out of 10). These are joined by reviews of both Operation Ogre (5 out of 10) and Caverns of Thracia (9 out of 10). This is, I think, a fairly representative sample of JG's output over the years – plenty of forgettable mediocrity but a number of true classics as well. Also reviewed is Yaquinto's game Time War, which receives a score of 8 out of 10.

"My Life as a Werebear" is an unusual article by Lewis Pulsipher. In it, he delves into the question of playing a monster as a character in Dungeons & Dragons. Pulsipher then provides for monster classes for use with the game. They're an odd assortment, consisting of the blink dog, lammasu, stone giant, and titular werebear. While I'm unsure I'd ever allow such characters in my own games, I think the guiding principles behind Pulsipher's designs are solid and the end results are good (though why anyone would want to play a blink dog character is beyond me). Shaun Fuller's "The Magic Brush" is a lengthy article on the finer points of painting miniature figures. Not being a painter myself, I can't speak to its utility, but it is clearly thorough in its treatment of its subject.

"The Sable Rose Affair" by Bob McWilliams is a superb scenario for use with Traveller. The adventure is quite detailed and includes lots of maps and NPCs, all of which contribute to its overall excellence. More noteworthy is its presentation as a series of "modules," which are discrete sections focusing on specific events or locales within the overall scenario. Depending on the approach the PCs take, only certain modules are needed, which offers the referee flexibility in how he adjudicates the course of play. "Treasure Chest" details seven new artifacts and relics, after the fashion of the mighty magic items found toward the end of the Dungeon Masters Guide. They're fine, as far as they go, though none really stand out as memorable.

The issue ends with an interview with Chaosium stalwart, Greg Stafford. It's a truly fascinating interview, one worthy of its own post (which I'll write either later today or tomorrow), in which Stafford talks at length not just about the origins of Glorantha, RuneQuest, and Chaosium but also his general philosophy of roleplaying and related activities. There's some eye-opening stuff in the interview serves as a good reminder – as if we needed one – of why Stafford was truly one of the greats of our hobby.

All in all, this was another fine issue, one that brings the magazine ever closer to the one I remember from just a few years later.

November 14, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: Lords of Tsámra

With a few exceptions, I am not a fan of "game fiction," which is to say, stories or novels that take place within a roleplaying game setting. There are a couple of reasons why this is so. The first is that most game fiction is written not by writers of literature – even pulp literature – but by game designers trying their hand at a new medium and, as such, isn't very well composed. The second, and in my mind more important reason, is that most game fiction just isn't very interesting. I'm actually quite forgiving of hackneyed writing and wooden characters, if the overall story being told is imaginative and introduces me to some aspect of its setting that I might otherwise not have encountered. Unfortunately, that's pretty rare, hence my skepticism toward books of this kind.

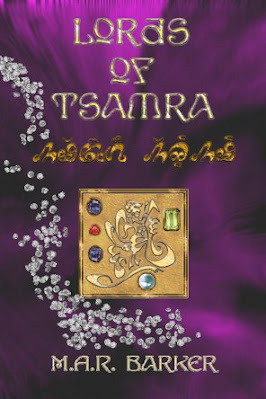

With a few exceptions, I am not a fan of "game fiction," which is to say, stories or novels that take place within a roleplaying game setting. There are a couple of reasons why this is so. The first is that most game fiction is written not by writers of literature – even pulp literature – but by game designers trying their hand at a new medium and, as such, isn't very well composed. The second, and in my mind more important reason, is that most game fiction just isn't very interesting. I'm actually quite forgiving of hackneyed writing and wooden characters, if the overall story being told is imaginative and introduces me to some aspect of its setting that I might otherwise not have encountered. Unfortunately, that's pretty rare, hence my skepticism toward books of this kind.But, as I said, there are a few exceptions and among those that quickly come to mind are the novels of M.A.R. Barker, creator of the world of Tékumel. Starting with 1984's The Man of Gold , Barker penned five Tékumel novels. As works of literature, they're of varying quality, but all of them contain compelling plots, memorable characters, and immense insights into Tékumel and its societies and cultures. Indeed, I'd argue that the novels do a far better job of presenting Tékumel to newcomers than do almost any of the RPG materials published for the setting since the appearance of Empire of the Petal Throne in 1975.

The third novel in the series, Lords of Tsámra, offers a good example of what I mean. Originally published in 2003, Lords of Tsámra takes place sometime after the events of the previous two novels in the series, The Man of Gold and Flamesong. The protagonist of the former, Hársan hiTikéshmu, re-appears here, though his role is secondary to that of an entirely new character, Korúkka hiKutonyál. Whereas Hársan is a priest of the gentle god of knowledge, Thúmis, Korúkka serves the grasping god of secrets, Ksárul. As such, he is a very different kind of person – arrogant, sneaky, and suspicious, but also thoughtful, quick-witted, and even brave when circumstances demand it of him. His differences from the more traditionally heroic character of Hársan makes him, I think, a more fascinating character. He's also a terrific window into the society of Tsolyánu, the titular Empire of the Petal Throne, whose inhabitants cannot be easily described in stereotypes.

The plot of the novel concerns a diplomatic mission sent from Tsolyánu to the Tsoléi Isles, to effect a cessation of hostilities between the Tsoléini and the Livyáni, another empire which was simultaneously involved in a wat against a third combatant, the Mu'ugalavyáni. If this all sounds confusing, on a certain level it is, but it's to Barker's credit that the reader is initiated slowly into the complicated geopolitics of Tékumel. It's a good thing, too, because, as Lords of Tsámra unfolds, more elements are added to the mix: a plague, conspiracies involving other-planar beings, and more. There's a lot going on in the novel and its characters are constantly tossed this way and that on tumultuous waves of plot not entirely of their own making. In this respect, Lords of Tsámra often reads like an old-fashioned pulp serial, filled as it is with perilous situations and unpredictable cliffhangers.

What saves the novel from becoming impossible to follow, let alone enjoy, is that, for all the clashes of nations and machinations of hidden cabals, its focus remains largely on the characters. This is the story of great events told from the ground, as it were. Everything that happens is seen through the eyes of Korúkka and his companions, as they navigate the strange cultures first of the Tsoléini and then the Livyáni (and a subculture within them, the Dláshi). Whatever his other weaknesses as a writer, Barker excels at offering his readers a kind of National Geographic-meets-Fodor's approach to the immensely rich world of Tékumel. Nearly every page of Lords of Tsámra describes some cultural detail, geographical description, or historical tidbit. One is slowly initiated into deeper mysteries along the way – some of them very deep indeed – the end of which is a better understanding of and appreciation for the remarkable fantasy world Barker has created.

Assuming that's what one wants out of a fantasy novel, Lords of Tsámra is a very good one; it's probably my favorite of all of Barker's Tékumel tales. That's not to say that the novel doesn't include its fair share of adventure and excitement. There's plenty here to hold the attention of fans of magic and swordplay, imminent danger and narrow escapes. That's not the focus of the novel, however, nor is it where Barker's skills shine. M.A.R. Barker is often compared to J.R.R. Tolkien in that he was a three-initialed linguist who created a rich fantasy setting. Another point of similarity is that, as a novelist, his strengths lie in describing his imaginary world and the varied people who inhabit it rather than on feats of derring-do. Pick up the novel with that in mind and I don't think you'll be disappointed.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers