James Maliszewski's Blog, page 124

December 14, 2021

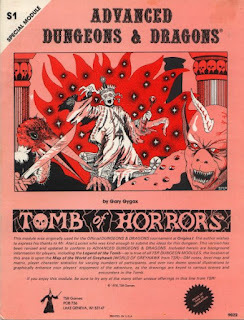

In Defense of the Green Devil Face

Even more than four decades since its publication in 1978, I think it's fair to say that Gary Gygax's Tomb of Horrors is a controversial module, with a sizable chorus of detractors. That's perfectly understandable in my opinion, given its difficulty and the seeming cruelty with which it was designed. I say "seeming," because, by most accounts, Gygax created the scenario as a challenge for very experienced players rather than as an exercise in mere sadism. Of course, this fact didn't stop many a Dungeon Master from taking vicious glee while inflicting it on player characters in his campaign. I suspect that much of the bad feeling toward the module stems in part to bad personal experiences with it and I cannot fault anyone for thus having reservations about it.

Even more than four decades since its publication in 1978, I think it's fair to say that Gary Gygax's Tomb of Horrors is a controversial module, with a sizable chorus of detractors. That's perfectly understandable in my opinion, given its difficulty and the seeming cruelty with which it was designed. I say "seeming," because, by most accounts, Gygax created the scenario as a challenge for very experienced players rather than as an exercise in mere sadism. Of course, this fact didn't stop many a Dungeon Master from taking vicious glee while inflicting it on player characters in his campaign. I suspect that much of the bad feeling toward the module stems in part to bad personal experiences with it and I cannot fault anyone for thus having reservations about it.Nevertheless, as I've stated on numerous occasions, I rate Tomb of Horrors very highly and indeed consider it one of the greatest D&D modules ever written. A big reason why is that, as Gygax states in his prefatory "Notes for the Dungeon Master," the dungeon "has more tricks and traps than it has monsters to fight." That makes it quite unusual among TSR's published adventures and something Gygax obviously considered important.

It is this writer's belief that brainwork is good for all players, and they will certainly benefit from this module, for individual levels of skill will be improved by reasoning and experience. If you regularly pose problems to be solved by brains and not brawn, your players will find this module immediately to their liking.

This is where the rubber hits the road, so to speak. A common criticism leveled at Tomb of Horrors is that, despite Gygax's statement – in capital letters, no less – that "THIS IS A THINKING PERSON'S MODULE," its tricks and traps are, in the main, unavoidable and nonsensical. Exhibit A in this line of thinking is the infamous "green devil face," more properly called "the face of the great green devil."

The green devil face occurs very early in the dungeon, at the end of the first corridor of the true tomb. The trap has the potential to kill a character instantly, without recourse to a saving throw, which is probably why it is so often mentioned as being emblematic of the fundamental unfairness of Tomb of Horrors. While I'm genuinely sympathetic to such a criticism, I don't think it's warranted. Take a look at the short description of the trap from the module:

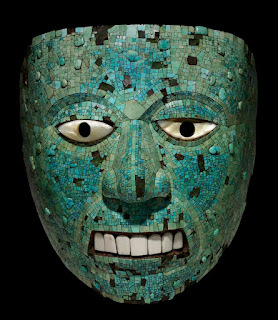

THE FACE OF THE GREAT GREEN DEVIL: The other fork of the path leads right up to an evil-appearing devil face set in mosaic at the corridor's end. (SHOW YOUR PLAYERS GRAPHIC #6). The face has a huge O of a mouth; it is dead black. The whole area radiates evil and magic if detected for. The mouth opening is similar to a (fixed) sphere of annihilation, but it is about 3' in diameter – plenty of room for those who wish to leap in and be completely and forever destroyed.

For the benefit of those who might have forgotten, here's Graphic #6 referenced in the text.

Perhaps this speaks poorly of my trust, but the only thing that could possibly make this illustration more suspicious is if the words "Free Candy" appeared somewhere in the darkness of its gaping maw. The text makes clear that the devil face is "evil-appearing," as does a mere visual examination of the face. The text likewise emphasizes the dead blackness of the mouth area and that it radiates evil if a character detects for it. I don't know how much more clear the threat posed by the green devil face could be.

Perhaps this speaks poorly of my trust, but the only thing that could possibly make this illustration more suspicious is if the words "Free Candy" appeared somewhere in the darkness of its gaping maw. The text makes clear that the devil face is "evil-appearing," as does a mere visual examination of the face. The text likewise emphasizes the dead blackness of the mouth area and that it radiates evil if a character detects for it. I don't know how much more clear the threat posed by the green devil face could be.I wonder how many characters truly died by leaping into the face's mouth. I've never witnessed it myself, but I'm sure it must have happened in some groups. Be that as it may, I don't think the green devil face is at all unfair. There are numerous clues that it's nothing to be trifled with; I expect even the most reckless of players would know better than to leap before they looked when it came to something so obviously sinister. In fact, I would like to suggest that the obviousness of this trap is the point. The green devil face is "Baby's First Death Trap." Gygax intended it as a clear signal of what was to come, a reminder to players to pay attention, lest their characters meet a terrible fate. Rather than being cruel, I think Gygax is being kind in starting things off with such a blatant trap.

The Arch of Mist, on the other hand …

White Dwarf: Issue #20

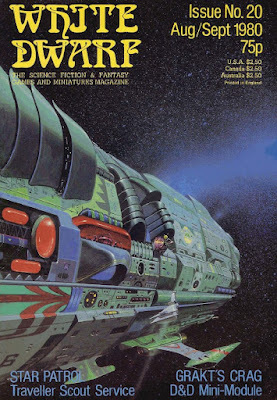

Issue #20 of White Dwarf (August/September 1980) features another science fiction-inspired cover by Angus McKie, which pleases me. As I said previously, I appreciate seeing SF ideas and themes like this, since I've always been more of a sci-fi fan than a fantasy one. White Dwarf – and UK gaming products in general – seemed quite comfortable with genre bending to a greater degree than contemporaneous US RPG publications. I'm not sure why that should be; I may even be mistaken in this impression, but that's certainly how it appears in hindsight.The issue begins with an interesting editorial by Ian Livingstone, in which he opines about the ever-contentious topic of alignment. Livingstone begins by musing that alignment ought to be "taken tongue-in-cheek." He then humorously asks, "Do they [i.e. players] stop to consider whether they are lawful good, neutral good, or lawful neutral before rushing into the tavern to decimate the dwarfs having lunch?" His point, it seems, is that, because roleplaying is, by definition, a fantasy, "why obey the codes of the real world?" "Why not," he wonders, "have a little fun while you're at it?," "fun" in this context being "hack and slay" without concern for the consequences. Unless Livingstone's point is simply that RPGs shouldn't be taken too seriously – a point I largely share – I'm not quite sure what to make of his editorial.

Issue #20 of White Dwarf (August/September 1980) features another science fiction-inspired cover by Angus McKie, which pleases me. As I said previously, I appreciate seeing SF ideas and themes like this, since I've always been more of a sci-fi fan than a fantasy one. White Dwarf – and UK gaming products in general – seemed quite comfortable with genre bending to a greater degree than contemporaneous US RPG publications. I'm not sure why that should be; I may even be mistaken in this impression, but that's certainly how it appears in hindsight.The issue begins with an interesting editorial by Ian Livingstone, in which he opines about the ever-contentious topic of alignment. Livingstone begins by musing that alignment ought to be "taken tongue-in-cheek." He then humorously asks, "Do they [i.e. players] stop to consider whether they are lawful good, neutral good, or lawful neutral before rushing into the tavern to decimate the dwarfs having lunch?" His point, it seems, is that, because roleplaying is, by definition, a fantasy, "why obey the codes of the real world?" "Why not," he wonders, "have a little fun while you're at it?," "fun" in this context being "hack and slay" without concern for the consequences. Unless Livingstone's point is simply that RPGs shouldn't be taken too seriously – a point I largely share – I'm not quite sure what to make of his editorial. "Dungeons & … Dragoons?" by Phil Masters is the first article of the issue. Masters offers up capsule descriptions and game statistics for a variety of troop types associated with historical cultures, such as Greek hoplites, Persian immortals, and Carolingian Franks. It's an odd little article, whose purpose is supposedly to expand the scope of D&D opponents beyond those grounded in medieval feudalism. Fan as I am in broadening the understanding of "fantasy," I'm not sure that this particular article offers much to achieve that end. On the other hand, Andy Slack's "Star Patrol" is quite successful in its goal of providing an advanced character generation system for the Scout service in Traveller. It's a very solid piece of work and does a much better job of it than does the official advanced Scout rules found in GDW's own Book 6.

"The Alchemist" by Tony Chamberlain is a new character class for use with Dungeons & Dragons. I must say I was disappointed, when I saw that Chamberlain intended it only as a class for NPCs, specifically the expert hirelings mentioned in the Dungeon Masters Guide. As presented, the class is basically a pared down version of the magic-user, with a limited spell selection and the ability to aid proper MUs in the creation of magic items. I've longed for a playable alchemist class to my liking since I was a kid, so I was quite disappointed to find this one brings me no closer to achieving that goal.

"Open Box" reviews multiple GDW products, starting with the SF wargame, Dark Nebula (9 out of 10). Dark Nebula is something of a white whale for me. I've never seen, let alone owned it, and hope one day to do so, if I can find a good copy at a reasonable price. Also reviewed are High Guard (8 out of 10), The Spinward Marches (9 out of 10), and Citizens of the Imperium (8 out of 10). Good to see lots of Traveller material represented here. The final reviews of this issue are TSR's The Awful Green Things from Outer Space (7 out of 10) and Philmar's The Mystic Wood (9 out of 10). I think this might be the first issue of White Dwarf where all the reviews are quite positive, with 7 out of 10 being the lowest score assigned to any product.

Will Stephenson's "Grakt's Crag" is an AD&D mini-module for 3rd-level characters. The adventure features the tomb of King Grakt, which has been built into the side of a mountain and reputed to be filled with many treasures. I remain impressed with the density of text in White Dwarf's various "mini-modules." They fit more material into three pages than many other magazines could in twice as much space. "The Fiend Factory" presents six new monsters for use with D&D, including the evil frog-folk and zombie-like cauldron-born.

Bob McWilliams gives us more Traveller material with the first installment of a new column called "Starbase." In this inaugural column, McWilliams briefly discusses how to start up a new Traveller campaign, with a focus on practical matters, such as the PCs' very first encounter. Meanwhile, "Treasure Chest" presents thirteen "Odd Items" – peculiar magic items like the whistle of pig calling and antacid. Rounding out the issue is Roger Musson's "Conversion," which looks postulates a new clerical ability, the aforesaid conversion. Musson lays out a simple system (akin to combat) by which a cleric can, through a combination of logic and casuistry, attempt to convert someone to his own faith. It's not a bad idea and it's one I've considered before myself, so naturally it was of interest. Musson's system has the benefit of being easy to use, if not necessarily "realistic," which is why I might actually consider making use of it.

With this issue, it's becoming more clear that White Dwarf, as I remember it, has nearly come into full existence by the second half of 1980. It will be fascinating to see if the recent trend in excellent content continues without interruption.

December 13, 2021

The Runners-Up

Selecting D&D modules for my Top 10 list was difficult – more difficult than I imagined it would be. Even limiting my choices to those published by TSR during the years between 1974–1983, there were a large number of viable choices. Inevitably, I excluded a few modules that, had I a larger list, I would probably have included. In the interests of clarifying my thought processes, I've decided to reveal five more modules for which I have great fondness but that, for one reason or another, I excluded. Unlike the previous two posts, I'm going to focus here on why I didn't select them for my Top 10. In some ways, this post might be even more illuminating than its predecessors.

These runners-up are ranked according to how close they came to making it onto my Top 10 list.

5. The Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth

5. The Lost Caverns of TsojcanthAs a kid, I adored this module, though much of my adoration came from the 32-page insert included with it. The insert featured a plethora of new monsters, many of them demons, which would later appear in the pages of the Monster Manual II, along with many new magic items. This sort of thing was like catnip to me at the time. But that insert is not the module itself. I've come to realize that, while the titular caverns are solid enough as an adventuring locale, they're not remarkable enough to warrant inclusion in my Top 10 list. With the benefit of hindsight, I realize now that my fondness for The Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth actually reflects my fondness for the year in which it was published – 1982 – and the possibilities I saw in AD&D's future rather than the content of the module proper. I still think there's a lot to like here, but not enough to have made my final cut.

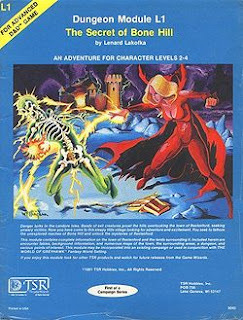

4. The Secret of Bone Hill

4. The Secret of Bone HillMy reasons for eliminating this module from the list was quite simple: it didn't see much use at my table back in the day. I've always regretted that. The Secret of Bone Hill is a very well presented low-level module. It has the potential, I think, to serve as a terrific kick-off to a new campaign. Indeed, I've heard of referees who've done just that and, by all accounts, this module is easily the equal of The Keep on the Borderlands and perhaps even The Village of Hommlet. But, as I said, my appreciation for it is largely academic, based almost entirely on reading its text rather than playing through it with others. As a kid, I swiped some elements of the module – like the skelters and zombires, which really impressed me at the time – for use in my own scenarios. I also repurposed some of its maps in a similar fashion. Beyond that, this was one of those modules I bought largely out of loyalty to TSR rather than because I expected to use it as intended.

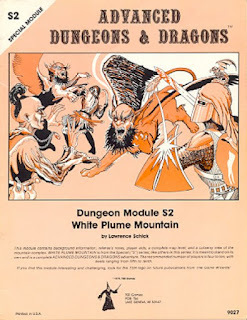

3. White Plume Mountain

3. White Plume MountainThis module is the quintessential "funhouse dungeon," which is why I so wanted to include it on my Top 10 list. Ultimately, it didn't make the final cut, because the list already included Castle Amber, a funhouse dungeon I played extensively and repeatedly back in my youth. Compared to that, White Plume Mountain is very much an also-ran. My friends and I had lots of fun with the module, but I only ever ran it once. In my Top 10 list, I placed a lot of importance of replayability and White Plume Mountain, for all its virtues, is more or less a one-and-done kind of dungeon. The characters go there for a specific reason – to recover the three stolen magic weapons – and, once they've achieved that goal, why go back? That's not a damning criticism, to be sure, but it's enough of one in my mind that I had no choice but to exclude it from my Top 10, despite my fondness for it.

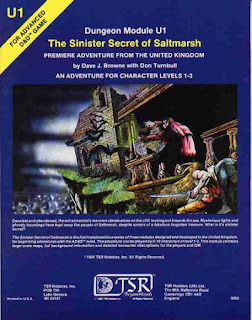

2. The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh

2. The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh Excluding this one hurts. In many respects, this module is perfect. It's got an excellent premise and is very well presented. That it's intended for use with beginning characters points even more strongly in its favor. On the other hand, its premise – that the supposedly haunted mansion of an alchemist is actually being used as a hideout for rather mundane bandits – works against it somewhat. I say that with some regret, as I quite like this "Scooby-Doo" approach, which I see as the culmination of Gygaxian naturalism in some respects. My experience, though, is that many players are disappointed when they discover that there's nothing actually supernatural going on and that everything happening has a purely rational explanation. Consequently, I have fewer fond memories of refereeing this than any of those included in my Top 10.

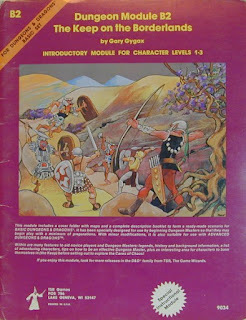

1. The Keep on the Borderlands

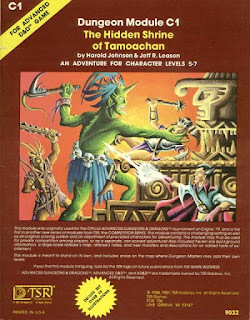

1. The Keep on the BorderlandsThis should not be a surprise. I have probably played module B2 more than any other D&D module, to the extent that I practically know many sections of it by heart. It's a fun scenario that's a great introduction to the game, so why not include it? Quite simply, I find it a little unimaginative these days. The titular keep feels very generic and underdeveloped (perhaps intentionally). The Caves of Chaos are a bit of a slog. Even the Shrine of Evil Chaos, which was my favorite part as a youth, feels lackluster, especially when compared to the lair of Lareth the Beautiful in The Village of Hommlet. These criticisms probably seem unfair and they might well be. I can only say that, speaking in 2021, I don't like The Keep on the Borderlands as much as I once did and that fact influenced my decision to keep it off the Top 10 list. Even so, I came very close to dropping The Hidden Shrine of the Tamoachan for it.

December 12, 2021

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Whisperer in Darkness

A couple of days ago, I re-watched the 2011 movie adaptation of "The Whisperer in Darkness" produced by the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. After doing so, I went back into the archive of my past posts to re-read my review of the film from 2012, as well as my Pulp Fantasy Library entry for the 1931 novelette on which it was based. While I was easily able to find the former, I was quite surprised to discover that I had never, in more than 250 entries in this series, written a post about "The Whisperer in Darkness." That was clearly a lacuna that needed to be filled and soon, hence today's post.

A couple of days ago, I re-watched the 2011 movie adaptation of "The Whisperer in Darkness" produced by the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. After doing so, I went back into the archive of my past posts to re-read my review of the film from 2012, as well as my Pulp Fantasy Library entry for the 1931 novelette on which it was based. While I was easily able to find the former, I was quite surprised to discover that I had never, in more than 250 entries in this series, written a post about "The Whisperer in Darkness." That was clearly a lacuna that needed to be filled and soon, hence today's post.

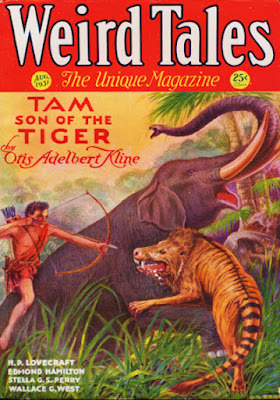

"The Whisperer in Darkness" is one of the longest stories H.P. Lovecraft ever wrote. At slightly more than 25,000 words, only four others – The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, At the Mountains of Madness, and "The Shadow over Innsmouth" – are longer and none ever earned Lovecraft more money ($350, which would have been a sizable sum at the time). The story appeared complete in the August 1931 issue of Weird Tales and was well received by the magazine's readership.

Like many of Lovecraft's best tales, this one was partially inspired by real life events, "the historic and unprecedented Vermont floods of November 3, 1927." The story's narrator, Albert N. Wilmarth, is "an instructor of literature at Miskatonic University in Arkham, Massachusetts, and an enthusiastic amateur student of New England folklore." The floods, Wilmarth explains, occasioned

certain odd stories of things found floating in some of the swollen rivers; so that many of my friends embarked on curious discussions and appealed to me to shed what light I could on the subject. I felt flattered at having my folklore study taken so seriously, and do what I could to belittle the wild, vague stories which seemed so clearly an outgrowth of rustic superstitions.

In addition to these "wild, vague stories" were reports of "organic shapes" washed along by the streams, shapes that were "not human, despite superficial resemblances in size and general outline."

They were pinkish things about five feet long, with crustaceous bodies bearing vast pairs of dorsal fins or membraneous wings and several sets of articulated limbs, and with a sort of convoluted ellipsoid, covered with multitudes of very short antennae, where a head would ordinarily be.

Wilmarth, naturally, is skeptical of these reports, which he considers echoes of "half-remembered folklore" from earlier generations. He was indeed familiar with such folklore himself, which spoke of "a hidden race of monstrous beings which lurked somewhere in the remoter hills–in the deep woods of the highest peaks, and the dark valleys where streams trickle from unknown sources." Other legends, like those of the Pennacook Indians, provided further details.

The Winged Ones came from the Great Bear in the sky, and had mines in our earthly hills whence they took a kind of stone they could not get on any other world. They did not live here, said the myths, but merely maintained outposts and flew back with vast cargoes of stone to their own stars in the north. They harmed only those earth-people who got too near them or spied upon them.

Wilmarth's skepticism leads him to debate "romanticists who insisted on trying to transfer to real life the fantastic lore of lurking 'little people'" in a series of letters published in the pages of the Arkham Advertiser. These letters are reprinted in several Vermont newspapers, which bring them to the attention of Henry Wentworth Akeley. Akeley writes directly to Wilmarth, telling him of his own experiences with the strange beings whose presence was revealed by the floods. He concurs with the Pennacook legends that the beings "come from another planet" and that they "come here to get metal from mines that go deep under hills."

The two men begin a correspondence. In his letters, Akeley claims to possess direct evidence of these alien lifeforms and their purposes on earth – photographs and even a phonograph recording of the beings. Wilmarth receives all of this in turn, which only adds to his suspicion that something is indeed going on in the backwoods of Vermont, something about which he'd like to know more. Their exchange of letters continues; Akeley recounts his growing fears of the creatures and their human agents. He worries that they mean to kill him and tells Wilmarth that, in the event he ceases communicating with him, he should assume the worst and inform his son George, who lives in California. In any event, he urges Wilmarth not to come to Vermont, lest he too suffer the attacks of these creatures.

Wilmarth states that "the letter frankly plunged me into the blackest of terror." His concern for Akeley's well-being increased with each passing day, until, at last, he received another letter from him. This new letter had an entirely different tone. Instead of fear, Akeley claimed that the alien beings, whom he now called "the Outer Ones" "have never knowingly harmed men." In fact, he claims that, all they "wish of man is peace and non-molestation and an increasing intellectual rapport." Akeley is now so certain of these facts that he practically begs Wilmarth to come up to Vermont to see him, so that he too can understand the truth. If he agrees, he asks Wilmarth to bring with him all their correspondence, including the photos and phonograph record he had sent to him, as they "shall need them in piecing together the whole tremendous story." Wilmarth agrees, setting the stage for the conclusion of the tale.

"The Whisperer in Darkness" is a good but flawed story. Its set-up is excellent, as are many of its ideas, not to mention Lovecraft's ominous evocations of rural Vermont. However, his handling of the Outer Ones is at times contradictory, both within the narrative of the story, and within his larger body of work. In his mature writings, Lovecraft is very concerned with properly portraying the alienness of the non-human beings he imagines. He wishes to show that they are not at all like human beings, in either their thoughts or their actions. Yet, the plot of "The Whisperer in Darkness" depends, to varying degrees, on the Outer Ones thinking and behaving in very human ways, at least once to the point of unintentional hilarity. I don't think this utterly ruins the story, which is, as I said, excellent in many ways. However, it does lessen its impact, especially when compared to a true masterpiece like, say, At the Mountains of Madness.

December 11, 2021

"Very Well Preserved"

Firstly, thanks to everyone who has offered their comments on my recent post about my House of Worms session reports. Ironically, given its subject matter, that post is now one of the most commented upon posts in recent months, disproving that readers of this blog are disinterested in commenting. If anything, I think, it suggests I need to up my own game by writing posts that better invite reader engagement. In any case, I encourage people to continue offering their thoughts, suggestions, and criticisms. I appreciate them all and hope to learn from them going forward.

Firstly, thanks to everyone who has offered their comments on my recent post about my House of Worms session reports. Ironically, given its subject matter, that post is now one of the most commented upon posts in recent months, disproving that readers of this blog are disinterested in commenting. If anything, I think, it suggests I need to up my own game by writing posts that better invite reader engagement. In any case, I encourage people to continue offering their thoughts, suggestions, and criticisms. I appreciate them all and hope to learn from them going forward.

To that end, I offer something light and, I hope, amusing from my House of Worms campaign. In a recent session, the player characters returned home to the Tsolyáni colony of Linyaró after an extended absence. Upon returning, one of the characters, Znayáshu, inquired after his wife, Tu'ásha, whom he had left behind to handle affairs of state in absence. (Znayáshu is the vice-governor for internal affairs in the colonial administration.)

What he discovered is that Tu'ásha was no longer in Linyaró, having journeyed in his absence to the Naqsái city-state of Pichánmush as an ambassador. Since the player characters had business in Pichánmush themselves, they assumed it'd be a simple matter to meet up with Tu'ásha there; such was not the case. Upon arrival in the city, they learned from a local government agent that Tu'ásha had been "detained," which is to say, taken prisoner. Naturally, this led to some pointed questions as to why and if she could now be released.

I'm not sure if I'd ever mentioned this before in any of my session reports, but Tu'ásha is undead. More specifically, she's a Shédra, an intelligent type of undead created by the temples of Hrü'ü, Ksárul, and especially Sárku. At the start of the campaign, all the way back in 2015, Znayáshu's player established said character was engaged but that his fiancée died as a result of too diligent practice of the rituals of the Brotherhood of the Amber Coiling (she had starved herself to death). Znayáshu had Tu'ásha's body carefully preserved after her death and intended to have her reanimated as a Shédra once he found someone who could do so. In the meantime, he kept her body in his private quarters at the House of Worms clanhouse in Sokátis.

Eventually, Znayáshu was able to secure the rite needed for Tu'ásha to begin her undead existence (though he did have to negotiate with her own clan for permission to do so). The temples of Sárku and Durritlámish, to which most members of the House of Worms clan belong, think nothing of the undead. In their beliefs, undeath is simply another stage of existence, one that preserves the most important parts of the self – the intellect and the body – so that they might better be able to witness the Coming Forth of Universal Diversification wrought by Lord Hrü'ü, the Supreme Principle of Change. Most other Tsolyáni are not quite so comfortable with the undead and, as a consequence, undead beings generally restrict themselves to the catacombs and underworlds of the empire.

Since Tu'ásha did not intend to confine herself to such darkened places, the decision was made that she would hide her undead status as best she could when traveling abroad. She covered her body as much as possible – unusual for the very hot world of Tékumel – and concealed her face behind a mask of jade. Only Znayáshu, her husband, regularly saw her in her true form. Most others simply believed her to be an eccentric, if frightening, woman in the employ of the governor of Linyaró.

The Naqsái of the Achgé Peninsula have a belief system unlike that of the Tsolyáni. In their worldview, Stability and Change are not separate things but instead two sides of the same coin, both of which are governed by Hánmu, the highest divine principle. As an undead being, the rulers of Pichánmush saw Tu'ásha as an abomination, an attempt to circumvent the natural order over which their god ruled. When she presented herself to them as Linyaró's ambassador, they took it as an affront. Fortunately for her, their longstanding diplomatic alliance with Linyaró stayed their hand; they did not destroy her but only imprisoned her.

When the player characters learned of this and asked for clarification, these facts were explained to them. Further, a local priest explained that Tu'ásha was "one of the soulless" and, therefore, anathema to the Naqsái. In further conversation, he referred to her as a "rotting shell," to which Chiyé, one the characters and a priest of Sárku himself, replied, "That's no way to talk about a man's wife." Znayáshu himself added, "I'll have you know, she's not rotting at all; she's very well preserved." In one of those moments that only makes sense if you were there, we all broke out into laughter. It was an unexpectedly funny release during a potentially tense moment in the session. It was also a good reminder of the kind of fun we regularly have in the campaign.

December 9, 2021

My Top 10 D&D Adventures of the Golden Age (Part II)

(Part I can be found here.)

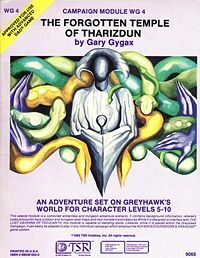

5. The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun

5. The Forgotten Temple of TharizdunThis is another module that has risen in my esteem as the years have gone on. Originally, I thought well of it primarily for its feel – creeping, claustrophobic oppression. I still admire it on the score, of course, but I now better appreciate the design of the dungeon itself, starting with the fact that it's quite well defended by the various evil humanoids that dwell within it. The characters can't just waltz up to the Temple and enter it without facing any opposition. Instead, they have to survive waves of humanoids trying to stop them. Once inside, there are still plenty of foes, as well as tricks and traps to overcome, culminating in the Black Cyst, which might be the prison of the dark god Tharizdun himself. I say "might," because Gygax never makes this clear and, in fact, shrouds a great deal in mystery. If you're looking for a cut-and-dried module, this one might disappoint; if you're looking for one rich in atmosphere and spooky enigmas, this one can't be beat.

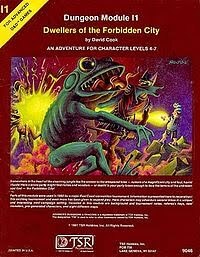

4. Dwellers of the Forbidden City

4. Dwellers of the Forbidden CityThis is a perfect example of a module I rank more highly than it probably would deserve, if I were making my judgments solely on the basis of design. As published, Dwellers of the Forbidden City is rough in places, even to the point of feeling incomplete. However, almost everything that is there is wonderfully evocative, from the mongrelmen to the aboleth to city itself and, of course, the despicable yuan-ti. The module is a terrific stew of ideas. David Cook clearly drank deeply from the same well as Tom Moldvay had when he wrote The Lost City, but each one feels unique. Also like The Lost City, Cook deliberately leaves many aspects of the city to the referee to develop on his own. One could easily spend months adventuring in and around the locales described here before exhausting their possibilities. That's just what I did and it's because of my fond memories of those times that I rank the module so high/

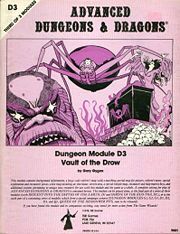

3. Vault of the Drow

3. Vault of the DrowFans of old school D&D tend to praise the G-D-Q series of modules more than they deserve. The giants modules are all solid, but, at base, they're all glorified dungeon crawls. Modules D1 and D2, especially the latter, are better, but they still somehow fall short of the promise implied by the appearance of the dark elves at the end of Hall of the Fire Giant King. Conversely, Vault of the Drow exceeds my expectations. Not only does it contain some of the finest examples of High Gygaxian prose ever penned by the Dungeon Master, the titular vault is a truly remarkable adventuring locale. Though filled with all manner of chaotic evil villainy, the characters are not expected to lay siege to the place. Instead, they must find a way to navigate its eerily-lit streets and warring factions to achieve their goals. It's an unusual adventure in an unusual locale and I love it.

2. Tomb of Horrors

2. Tomb of Horrors You can be forgiven if you expected that this 1980 module would have been at the top of my list. Tomb of Horrors is indeed a fine module. It's likely the most famous of all D&D modules, simply because of its reputation for being the king of killer dungeons. However, it's precisely for that reason that I can't give it the number one spot on my list, no matter how highly I regard it. Unlike most of the other modules on this list, the Tomb doesn't have a lot of potential as a campaign locale to which the characters can return again and again. It's more or less a one-and-done kind of place, albeit one that may claim the lives of many characters before it's finally "beaten." On the other hand, the insidious cleverness of its many tricks and traps can never be beaten. This is a masterclass on how to present a challenging dungeon almost entirely bereft of monsters. Sure, it doesn't play entirely fair and some of its features are downright mean, but then that's the point, isn't it?

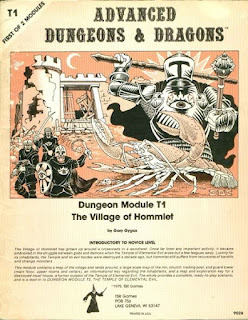

1. The Village of Hommlet

1. The Village of HommletSimply put, this is the module that makes me want to play Dungeons & Dragons. Firstly, it's a low-level adventure, perfect for kicking off a new campaign and who doesn't love the promise of a new campaign? Secondly, Hommlet itself is a delightfully detailed little village, inhabited by charming (and secretly sinister) NPCs. Thirdly, the Moathouse pretty much embodies the "perfect dungeon" for me, containing as it does just the right mix of elements to excite my imagination. Finally, the backstory of the adventure – the rise and fall of the Temple of Elemental Evil – does a great job of not only providing context for the module itself but also propels the campaign toward bigger, looming threats. In short, The Village of Hommlet is, to my mind, a near-ideal first adventure module for both inexperienced and experienced referees and players alike. I love it.

Whatever Happened to the House of Worms?

The House of Worms is the Empire of the Petal Throne campaign I've been refereeing since March 2015. Until a few months ago, I wrote regular posts briefly detailing the actions of the player characters in it. Though the campaign is still ongoing, I stopped writing those posts because I began to question the utility of doing so. They are consistently among the least read and commented upon posts on this blog. Few of them cracked 200 unique views and most have no comments on them at all. Aside from a single player in the campaign, almost no one has asked me why I stopped writing them or encouraged me to start doing so again.

I write this with a little disappointment. I am very much aware of how few people have any knowledge of or interest in Tékumel. It is and always has been an exceedingly niche setting within the wider hobby. Likewise, it's been my experience that campaign play reports rank only slightly higher in people's affections than being cornered by a fellow at a con who wants to tell you about his character.

On some level, this is understandable. Most campaigns, especially long running ones, take on the nature of a "you had to be there" joke. Even if my posts were immensely long and detailed, there's no way a reader could properly appreciate the context of what's happening. In our most recent sessions, for example, the characters embarked on the investigation of several mysteries whose seeds were planted years ago, before some of the campaign's seven current players had even joined it. Expecting readers to find much interest in these posts is thus probably too much to expect.

At the same time, I remain convinced that long-term campaign play represents the highest form of roleplaying and that the best way to demonstrate this conviction is by showing the unparalleled joys of such a campaign. March of next year will mark the seventh anniversary of the House of Worms campaign, making it the single longest RPG campaign I've ever continuously played with the same group of people. My players tell me that this is true of them as well. I suspect that, with a few exceptions, this is true of most readers of this blog. Heck, I'd wager that it's probably true of most roleplayers, period.

I had naively hoped, back when I started posting session reports, that they might at least encourage some discussion of the care and maintenance of long campaigns, because I think this is something of a lost art. The impression I increasingly get is that much of our hobby is devoted to idle consumerism – the never-satiated pursuit of the latest baubles – and not much play of any kind, never mind dedicated campaign play. I've sometimes darkly mused that the interest in so-called "actual play" videos and streams serves as a substitute for playing oneself.

Perhaps I conclude too much from the lack of interest in the House of Worms session report posts. It may simply be, as I noted above, that Tékumel is such a niche interest that even those theoretically interested in campaign play are turned off by the setting itself. If so, that's fair enough; we like what we like and there's no point in trying to argue otherwise. If it's something else, though, I'd be curious to know, especially if it's something I could do differently. As it is, those posts take a long time to write, far longer than one might expect based on the word count. That's because I try to condense them down into something relatively brief and intelligible to people not deeply immersed in the setting. There are limits to what I can do and it may well be that, despite my wishes to the contrary, there is simply no way to make these posts more appealing.

Regardless, I'd be grateful for any specific thoughts readers have on the matter. The House of Worms campaign is a huge part of my gaming these days and I'd like to use it as the springboard for more posts here. However, I have no interest in boring anyone, if it's not a subject that's of wide interest (which is what Blogger's stats tell me).

My Top 10 D&D Adventures of the Golden Age (Part I)

By far and away, the most popular post I've ever written on this blog is one of its earliest ones. Entitled "30 Greatest D&D Adventures of All Time," the post is a brief commentary on a list published in issue #116 of Dungeon magazine, in which I offered my thoughts on the entries included in this list. The list includes modules from the entire history of Dungeons & Dragons up until that point (2004) and its choices, as I say in my post, are idiosyncratic to say the least. Even so, the list is a good conversation starter and I've had many fruitful discussions of the merits and flaws of various D&D modules over the years.

Recently, a long-time reader of this blog asked me if I'd ever written a post in which I ranked the modules of D&D's golden age. As it turned out, I had not and, with his encouragement, I started thinking about doing so. Unlike my reader, I wasn't prepared to look at all the adventures published for D&D during the period between 1974 and 1983. Instead, I decided to restrict myself solely to those published by TSR during that period. Further, I was only going to rank my top ten.

Please note the possessive pronoun. What follows is the first part of a list of the ten D&D adventure modules published by TSR during the game's golden age, ranked according to my own tastes. I make no claims that my preferences are, let alone should be, universal. Nevertheless, I will make an effort to explain the reasons I've included every module on this list. I hope that doing so will provide not just some context to my own ranking but also engender wider conversation about the classics of the early days of Dungeons & Dragons.

10. The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan

10. The Hidden Shrine of TamoachanOf all the modules in my list, this is the one whose esteem in my eyes has risen the most. That's because, with the benefit of hindsight, I better appreciate the cleverness of its design. While there are a handful of monsters to be found here, such as the first appearance of the gibbering mouther, the real attractions are the shrine's many tricks and traps. Speaking as someone who's often had difficulty coming up with such things, I can't help but admire the imaginations of Harold Johnson and Jeff R. Leason. They succeeded in creating a good mix of challenges for both brain and brawn, which is precisely what a good dungeon requires to be memorable and fun. Couple this with the Mesoamerican vibe of the shrine – used to good effect in the included illustration booklet – and you've got a winner. One of these days, I ought to try running it again to see if I can use it to better effect than I did as a kid. Given the quality of its design, I suspect I can.

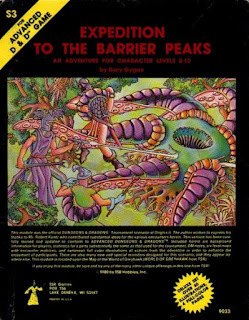

9. Expedition to the Barrier Peaks

9. Expedition to the Barrier PeaksPublished in 1980, this is the first (but not the last) time Gary Gygax's byline is seen on this last. As a kid, I was somewhat ambivalent about this module, given its inclusion of explicitly science fictional elements, but, nowadays, such genre bending appeals to me a lot more. Beyond that, the module features lots of unique encounters, not just with the alien animals living aboard the wrecked spaceship – who can forget the froghemoth? – but with some of the weird denizens of the Monster Manual, like the mind flayer and the intellect devourer. Equally memorable are the striking visual designs of the high technology scattered throughout the ship. Few of them look anything like what players would expect of a futuristic weapon, which very nicely simulates how medieval fantasy characters might look on such things the first time they encounter them. Finally, the design of the ship's decks deserve praise too.

8. The Lost City

8. The Lost City I simply adore this module. The only reason it isn't rated higher is that there are so many excellent candidates for this list and inevitably one of them would have to occupy this rank. Part of what I regularly call Tom Moldvay's "Pulp Fantasy Trilogy," (the other parts to be discussed shortly) The Lost City is a great evocation of, as its name suggests, the "lost city" genre that was a staple of pulp fiction (Howard's "Red Nails" probably being one of the most relevant examples for our purposes.) That Moldvay wrote the adventure for low-level characters is, to my mind, one of its best features. Too often scenarios of this sort are reserved to higher levels, on the assumption that the lost civilization contains mighty wonders and terrors suitable only for potent PCs. Moldvay, on the other hand, offers up the titular city as the starting point for a whole campaign, one that could potentially take those low-level characters to much greater heights of power and importance. That's how it's done.

7. The Isle of Dread

7. The Isle of DreadThis was the adventure module that first taught me the joys of wilderness exploration, an aspect of D&D with which I still sometimes struggle to this day. Together, David Cook and Tom Moldvay present a delightfully open-ended locale, populated by all manner of monsters and NPC. Though the promise of treasure is what initially draws the characters to the Isle, there's so much more to do there, whether it be fighting prehistoric monsters, negotiating with the natives, or even just filling in every hex on the blank map they're carrying with them. When I first refereed this in my youth, the player characters spent many sessions on the Isle, scouring every hex in search of its mysteries. In the process, they ran afoul of pirates who would eventually become recurring antagonists for a time. The module is also notable for having presented a map and brief gazetteer of the "Known World" fantasy setting.

6. Castle Amber

6. Castle AmberThis module ranks so high for me, because it was my introduction to the fiction of Clark Ashton Smith, thereby initiating a lifelong fascination with the Bard of Auburn and his works. Of course, Castle Amber is a genuinely fun adventure, provided you're in the mood for a funhouse dungeon. What I like about this module is that, while it is a funhouse, filled with bizarre and occasionally silly things, it's not completely inexplicable. There's an underlying logic to the place and its inhabitants. There are reasons why the Amber family behaves as they do and uncovering those reasons play a large role in the fun of this adventure – assuming you survive. I know many aficionados of old school D&D point to Judges Guild's Tegel Manor as the best example of this style of "wild and woolly" module, but, for my money, Castle Amber is better written and presented and overall more fun. It's a true classic and worthy of more praise than it typically gets.

December 7, 2021

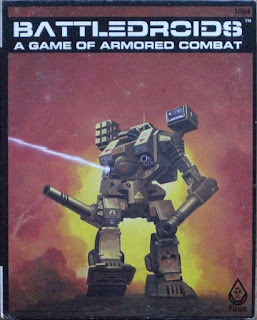

Retrospective: Battledroids

If you were a fan of GDW's Traveller in the early 1980s, as I was, chances are good that you were familiar with the publications of a small Chicago-based licensee, FASA (which originally stood for "Freedonian Aeronautics and Space Administration"). Starting in 1980, FASA published more than two dozen products to support Traveller, many of them being or including starship deckplans. Much of their output was the work of the tireless Keith Brothers, whose "Sky Raiders" trilogy of adventures remains one of the high points of FASA's time as a GDW licensee. Lots of old Traveller hands thus have very fond memories of FASA and its contributions to their favorite science fiction RPG.The combination of my affection for its Traveller products and its publication of Star Trek in 1982 ensured that I kept my eye on FASA, despite my loyalty to TSR Hobbies. Sometime in 1984, I took notice of an announcement that the company was producing a miniatures-based "game of armored combat" set a millennium in the future called Battledroids. I distinctly recall being intrigued by the cover art, which featured a giant robotic war machine striding into battle. You have to remember that this was a year or so before Robotech aired on TV screens in North America, so I wasn't all that familiar with the idea of a walking tank outside of the AT-ATs in The Empire Strikes Back. Consequently, I was quite taken with the premise of Battledroids and hoped to check it out once it was released.

If you were a fan of GDW's Traveller in the early 1980s, as I was, chances are good that you were familiar with the publications of a small Chicago-based licensee, FASA (which originally stood for "Freedonian Aeronautics and Space Administration"). Starting in 1980, FASA published more than two dozen products to support Traveller, many of them being or including starship deckplans. Much of their output was the work of the tireless Keith Brothers, whose "Sky Raiders" trilogy of adventures remains one of the high points of FASA's time as a GDW licensee. Lots of old Traveller hands thus have very fond memories of FASA and its contributions to their favorite science fiction RPG.The combination of my affection for its Traveller products and its publication of Star Trek in 1982 ensured that I kept my eye on FASA, despite my loyalty to TSR Hobbies. Sometime in 1984, I took notice of an announcement that the company was producing a miniatures-based "game of armored combat" set a millennium in the future called Battledroids. I distinctly recall being intrigued by the cover art, which featured a giant robotic war machine striding into battle. You have to remember that this was a year or so before Robotech aired on TV screens in North America, so I wasn't all that familiar with the idea of a walking tank outside of the AT-ATs in The Empire Strikes Back. Consequently, I was quite taken with the premise of Battledroids and hoped to check it out once it was released.Unfortunately for me, I never saw the game at any of my local hobby shops and soon forgot about it. It wasn't until several years later, when I started college that I again encountered Battledroids, though by this time FASA had changed its name to Battletech, the name by which it is known nowadays. What grabbed my attention at this time wasn't the game itself. Rather, it was a huge map I saw hanging on the wall of a game store that depicted the Inner Sphere, the interstellar setting of Battletech. I'm a sucker for maps, as many gamers are, and this one, filled as it was with literally hundreds of named star systems, was immensely attractive to me. Equally appealing were the illustrations (by David Dietrick) of soldiers and mercenaries from the Battletech setting. The variety of their uniforms impressed me greatly; those illustrations suggested that the Inner Sphere had a history and a culture (or cultures) and I wanted to learn more about it.

I did eventually get to see the original Battledroids game, which was very simple. The rules were contained in a 32-page booklet that covered basic, advanced, and expert play. I remember thinking this was an interesting way to present the game, since it allowed a newcomer to play a simple version of it almost immediately upon opening the box. The later sections added to that simple version by introducing layers of complexity. The other thing I recall liking about the rules were the record sheets for the battledroids. They had a diagram of each droid that included little checkboxes to keep track of damage. I won't claim this was an inspired design or that no one had ever done it before, but I thought it simultaneously both elegant and immersive.

The game also included map sheets, cardboard markers and tokens, and two plastic battledroid figurines, along with dice. Those little plastic models, as terrible as they were, demonstrated to me the possibilities of this game. The thought of an entire tabletop battlefield filled with these little war machines captured my imagination and I looked forward to the inevitable release of metal versions from Ral Partha. Though I owned a few science fiction miniatures, they never evoked much from my imagination, I'm sorry to say. I saw great potential in the battledroids, though.

The rulebook provided an overview of the setting of Battledroids, talking about the collapse of the United Star League and the Dark Age of the Succession Wars that followed. The term "Dark Age" is no hyperbole; the five successor states of the League have lost the ability to make new battledroids, making them immensely valuable – and their pilots (or droidwarriors, as they were called) celebrated. Battles are fought over resources to maintain and repair the existing battledroids and the rulebook provides information on the nature of this warfare in the 30th century. I don't know that any of this holds up to much scrutiny but there's no question that I found it all quite compelling at the time.

Even now, I find the idea of the Battletech setting very attractive, even if I'm not sure I fully embrace it enough to enjoy it uncritically. The fact that Battletech today still exists is proof, though, that FASA succeeded in creating something imaginatively enduring. And to think it all began with a couple of little plastic figures and some cardboard cut-outs. Not bad!

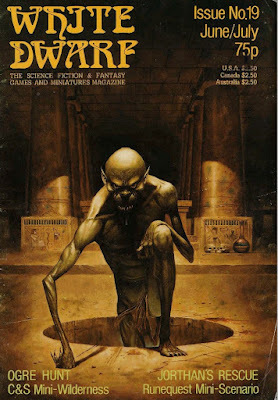

White Dwarf: Issue #19

Issue #19 of White Dwarf (June/July 1980) features a wonderfully creepy cover illustration by Les Edwards, which I am certain I have seen before – perhaps several times. Unfortunately, my memory isn't what it used to be and I can't quite recall where else I might have gazed upon its magnificence. If any reader's brain is less addled than mine, I'd appreciate a helpful reminder.

Issue #19 of White Dwarf (June/July 1980) features a wonderfully creepy cover illustration by Les Edwards, which I am certain I have seen before – perhaps several times. Unfortunately, my memory isn't what it used to be and I can't quite recall where else I might have gazed upon its magnificence. If any reader's brain is less addled than mine, I'd appreciate a helpful reminder.

Ian Livingstone's opening editorial suggests that White Dwarf is doing well and so firmly established in the UK gaming scene that newcomers to it are seeking out back issues. However, he notes that many of these early issues are no longer in print and that, "due to recent increased printing costs," it is not economically feasible to reprint them. Instead, Games Workshop would soon be releasing two compendiums of material derived from early issues, one focusing on articles and one on scenarios. Relatedly, the same increased costs had necessitated a rise in the price of WD – 75p instead of 60p – though four more pages had been added in compensation.

The issue kicks off with Trevor Graver's "Criminals" for Traveller, which presents alternate careers for use with GDW's science fiction RPG. It's a good article in my opinion, though its career format is closer to that of Mercenary than the three little black books of 1977. That's not a damning criticism by any means, but I retain a preference for "basic" character generation over the "advanced" ones presented in later books. More interesting is its approach to ranks, which here are reimagined as "reputation" and map onto the criminal character's notoriety in the galactic underworld (and his worth as a bounty).

"The Fiend Factory" continues, this time under the editorship of Albie Fiore. Don Turnbull, who originated the column, recently left White Dwarf to take up his duties as head of the new TSR UK. Fiore presents five new monsters, including two varieties of undead horses (one skeletal and one zombie-like). Elsewhere, Stephen Marsh and John Sapienza are the authors of a RuneQuest mini-scenario entitled "Jorthan's Rescue." The scenario concerns a wealthy noble, the titular Jorthan, who has been kidnapped by trollkin and whose wife hires the characters to bring him back alive. Intriguingly, the scenario includes two different versions of the map of the trollkin's lair, one more complex than the other, depending on the needs of the referee. I can't recall ever seeing a scenario that did something like this before, though, as I said at the start of this post, my memory isn't what it used to be.

Roger E. Moore, who would one day go on to be editor-in-chief of TSR's own Dragon magazine, has written "Berserker," a new character class for use with Dungeons & Dragons. The class is very similar in broad outline to the barbarian class we'd later see in D&D's Third Edition, with a focus on "battle lust," which empowers the berserkers attacks. Also included is an option for "berserker clerics" dedicated to appropriate gods of war or physical prowess. Intriguingly, there's a brief discussion of lycanthropic berserkers, no doubt due to the influence of the "bear-shirts" of Norse legend. Over the years, I've vacillated wildly in my feelings about additional and alternate character classes. These days, I'm much more well inclined toward them, which no doubt colors my generally positive opinion of this article.

"Ogre Hunt" by Tom Keenes is a mini-scenario for use with Chivalry & Sorcery. It's a pretty straightforward adventure, consisting of a brief wilderness journey to find the ruined tower where Moribund the Ogre dwells. Said ogre is terrorizing the countryside and so Lady Cynthia is offering a reward to anyone who can slay him. There adventure is nothing special in itself, but I appreciate seeing something written for C&S, a game for which I have an odd fondness, despite never having played it. "Open Box" presents five reviews, starting with Task Force's Starfire (8 out of 10) and Avalon Hill's Magic Realm (7 out of 10). Also reviewed are High Fantasy and Fortress Ellendar (4 and 7 out of 10 respectively). as well as Kinunir for Traveller (9 out of 10).

"Wards" by Lewis Pulsipher is a short article on magical barriers erected by magic-users to protect valuable locations and objects. Pulsipher offers four examples of such wards, including the spells needed to create them. Though brief, it's a clever idea and the kind of thing I appreciate seeing, namely an addition to D&D that doesn't require any new rules, only a repurposing of existing ones. "Treasure Chest" takes an unusual turn by presenting ten different NPCs for use with D&D. Most of them aren't all that special to my mind, but a few, like Fred, Bill, and Charly, a trio of troublesome and reckless fighting men rise above the pack. The issue closes with Chris Harvey's look at the computer moderated postal wargame, Starweb. Articles like this are time capsules of a very specific era, when the computer was a strange new technology and no one quite new what to make of them.

Issue #19 was a fine one. White Dwarf has truly begun to hit its stride. Bring on issue #20!

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers