Pulp Fantasy Library: The Whisperer in Darkness

A couple of days ago, I re-watched the 2011 movie adaptation of "The Whisperer in Darkness" produced by the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. After doing so, I went back into the archive of my past posts to re-read my review of the film from 2012, as well as my Pulp Fantasy Library entry for the 1931 novelette on which it was based. While I was easily able to find the former, I was quite surprised to discover that I had never, in more than 250 entries in this series, written a post about "The Whisperer in Darkness." That was clearly a lacuna that needed to be filled and soon, hence today's post.

A couple of days ago, I re-watched the 2011 movie adaptation of "The Whisperer in Darkness" produced by the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. After doing so, I went back into the archive of my past posts to re-read my review of the film from 2012, as well as my Pulp Fantasy Library entry for the 1931 novelette on which it was based. While I was easily able to find the former, I was quite surprised to discover that I had never, in more than 250 entries in this series, written a post about "The Whisperer in Darkness." That was clearly a lacuna that needed to be filled and soon, hence today's post.

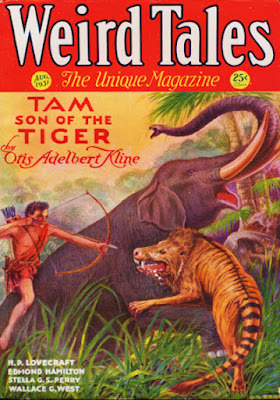

"The Whisperer in Darkness" is one of the longest stories H.P. Lovecraft ever wrote. At slightly more than 25,000 words, only four others – The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, At the Mountains of Madness, and "The Shadow over Innsmouth" – are longer and none ever earned Lovecraft more money ($350, which would have been a sizable sum at the time). The story appeared complete in the August 1931 issue of Weird Tales and was well received by the magazine's readership.

Like many of Lovecraft's best tales, this one was partially inspired by real life events, "the historic and unprecedented Vermont floods of November 3, 1927." The story's narrator, Albert N. Wilmarth, is "an instructor of literature at Miskatonic University in Arkham, Massachusetts, and an enthusiastic amateur student of New England folklore." The floods, Wilmarth explains, occasioned

certain odd stories of things found floating in some of the swollen rivers; so that many of my friends embarked on curious discussions and appealed to me to shed what light I could on the subject. I felt flattered at having my folklore study taken so seriously, and do what I could to belittle the wild, vague stories which seemed so clearly an outgrowth of rustic superstitions.

In addition to these "wild, vague stories" were reports of "organic shapes" washed along by the streams, shapes that were "not human, despite superficial resemblances in size and general outline."

They were pinkish things about five feet long, with crustaceous bodies bearing vast pairs of dorsal fins or membraneous wings and several sets of articulated limbs, and with a sort of convoluted ellipsoid, covered with multitudes of very short antennae, where a head would ordinarily be.

Wilmarth, naturally, is skeptical of these reports, which he considers echoes of "half-remembered folklore" from earlier generations. He was indeed familiar with such folklore himself, which spoke of "a hidden race of monstrous beings which lurked somewhere in the remoter hills–in the deep woods of the highest peaks, and the dark valleys where streams trickle from unknown sources." Other legends, like those of the Pennacook Indians, provided further details.

The Winged Ones came from the Great Bear in the sky, and had mines in our earthly hills whence they took a kind of stone they could not get on any other world. They did not live here, said the myths, but merely maintained outposts and flew back with vast cargoes of stone to their own stars in the north. They harmed only those earth-people who got too near them or spied upon them.

Wilmarth's skepticism leads him to debate "romanticists who insisted on trying to transfer to real life the fantastic lore of lurking 'little people'" in a series of letters published in the pages of the Arkham Advertiser. These letters are reprinted in several Vermont newspapers, which bring them to the attention of Henry Wentworth Akeley. Akeley writes directly to Wilmarth, telling him of his own experiences with the strange beings whose presence was revealed by the floods. He concurs with the Pennacook legends that the beings "come from another planet" and that they "come here to get metal from mines that go deep under hills."

The two men begin a correspondence. In his letters, Akeley claims to possess direct evidence of these alien lifeforms and their purposes on earth – photographs and even a phonograph recording of the beings. Wilmarth receives all of this in turn, which only adds to his suspicion that something is indeed going on in the backwoods of Vermont, something about which he'd like to know more. Their exchange of letters continues; Akeley recounts his growing fears of the creatures and their human agents. He worries that they mean to kill him and tells Wilmarth that, in the event he ceases communicating with him, he should assume the worst and inform his son George, who lives in California. In any event, he urges Wilmarth not to come to Vermont, lest he too suffer the attacks of these creatures.

Wilmarth states that "the letter frankly plunged me into the blackest of terror." His concern for Akeley's well-being increased with each passing day, until, at last, he received another letter from him. This new letter had an entirely different tone. Instead of fear, Akeley claimed that the alien beings, whom he now called "the Outer Ones" "have never knowingly harmed men." In fact, he claims that, all they "wish of man is peace and non-molestation and an increasing intellectual rapport." Akeley is now so certain of these facts that he practically begs Wilmarth to come up to Vermont to see him, so that he too can understand the truth. If he agrees, he asks Wilmarth to bring with him all their correspondence, including the photos and phonograph record he had sent to him, as they "shall need them in piecing together the whole tremendous story." Wilmarth agrees, setting the stage for the conclusion of the tale.

"The Whisperer in Darkness" is a good but flawed story. Its set-up is excellent, as are many of its ideas, not to mention Lovecraft's ominous evocations of rural Vermont. However, his handling of the Outer Ones is at times contradictory, both within the narrative of the story, and within his larger body of work. In his mature writings, Lovecraft is very concerned with properly portraying the alienness of the non-human beings he imagines. He wishes to show that they are not at all like human beings, in either their thoughts or their actions. Yet, the plot of "The Whisperer in Darkness" depends, to varying degrees, on the Outer Ones thinking and behaving in very human ways, at least once to the point of unintentional hilarity. I don't think this utterly ruins the story, which is, as I said, excellent in many ways. However, it does lessen its impact, especially when compared to a true masterpiece like, say, At the Mountains of Madness.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers