James Maliszewski's Blog, page 116

February 19, 2022

Here We Go Again

Issue #39 of Dragon (July 1980) featured an article on critical hits entitled "Good Hits and Bad Misses" by Carl Parlagreco. I've mentioned before that this article had a huge effect on me in the early days of my gaming; I carried around a photocopy of its tables in my DM binder for years. Apparently, Gary Gygax didn't think as well of it as I. He wrote a letter Dragon on the matter, which appeared in issue #41 (September 1980), in which he not only mocks the idea of critical hits and misses but also offers up his own ideas on (tongue-in-cheek?) ideas on the subject:

February 18, 2022

"Particularly Offensive to the Precepts of D&D"

After writing my post on double damage and "instant death," I started looking into the history of critical hits in roleplaying games. In doing so, I came across an installment of Gary Gygax's "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" column in issue #16 of Dragon (July 1978). Among many other topics, Gygax touches on the topic of critical hits. This is, I believe, the first time he specifically addresses the topic in print (though I'm prepared to be corrected, if I've overlooked an earlier text on the subject).

Purely from a historical point of view, Gygax's position strikes me as odd. Firstly, there's the matter of Empire of the Petal Throne, published by TSR in 1975. EPT includes critical hits, the first published roleplaying game to do so, and yet I can find no evidence that Gygax was particularly exercised about the inclusion of this mechanical innovation. I suppose it's possible that his opinion on the matter changed. After all, the section about appeared in 1978, which is more than enough time for him to have decided, on reflection, that critical hits were a problem.

Purely from a historical point of view, Gygax's position strikes me as odd. Firstly, there's the matter of Empire of the Petal Throne, published by TSR in 1975. EPT includes critical hits, the first published roleplaying game to do so, and yet I can find no evidence that Gygax was particularly exercised about the inclusion of this mechanical innovation. I suppose it's possible that his opinion on the matter changed. After all, the section about appeared in 1978, which is more than enough time for him to have decided, on reflection, that critical hits were a problem.Alternatively, it's possible that Gygax's condemnation of critical hits was a narrow one. He calls them "particularly offensive to the precepts of D&D," not "to the precepts of roleplaying games." He may simply have felt that Dungeons & Dragons was designed with a particular type of experience in mind and that critical hits ran counter to that design. Thus, the presence of critical hits in EPT was of no concern to him, since his opinion was solely concerned with D&D.

However, if that's the case, we have to reckon with the existence of the sword of sharpness and vorpal blade, two magical weapons introduced in Supplement I: Greyhawk in 1975, the same year as Empire of the Petal Throne was published. These weapons include the possibility of instant death by the severing of an opponent's neck and the possibility of this happening is much greater than that of an instant death critical hit in EPT or even the more traditional "double damage on the roll of a natural 20" favored by most versions of the rule in wider circulation. No doubt Gygax would (reasonably) say that these weapons are rare and their inclusion is entirely up to the individual referee. Still, I think there's more than a little mechanical similarity between the way these weapons work and critical hits and that somewhat undercuts Gygax's stated position.

From a purely personal perspective, I can't quite recall when I first encountered the concept of critical hits, but I suspect it was quite early in my introduction to the hobby. By the early '80s, critical hits were one of those rules that everyone knew about and many used, even without being able to point to a section of D&D's actual rules that supported them. For many years, I carried around a photocopy of the critical hit tables from issue #39 (July 1980) and occasionally made use of them. I've never had any really strong feelings for or against the concept, which is why I find Gygax's vehement denunciation of them so odd.

February 17, 2022

Amazon!

One of the best things about re-reading gaming magazines from the early days of the hobby is finding illustrations by well known artists that you'd never seen before. A good case in point is Erol Otus, who's probably most remembered for his work on the 1981 Basic and Expert sets (especially their iconic covers). During his tenure at TSR, he also did a number of pieces – many of them in color – that appeared in the pages of Dragon, such as the one below from issue #43 (November 1980). The illustration accompanied a write-up for Amazons written by Roger E. Moore.

A Radical Proposal (Part II) Follow-Up

Last week, I proposed, without explanation, the names of six abilities – Strength, Knowledge, Willpower, Dexterity, Constitution, and Acumen. Readers quite reasonably assumed these abilities were intended as replacements for those in Dungeons & Dragons. In truth, they're part of my process of thinking out loud about The Secrets of sha-Arthan setting that I'm continuing to develop, albeit more slowly than I'd like. Now, the rules for Secrets are based heavily on those of D&D, specifically those found in the Basic and Expert rulebooks (and their closest contemporary clone, Old School Essentials), so there's a fair degree of overlap. Nevertheless, most of my thoughts on these matter pertain specifically to this current project of mine, even if there is applicability to D&D more generally.

After further thought and reading many of the comments posted to that post and related ones, my thinking continues to shift. However, in the interests of furthering what has proven to be a very useful conversation – and I'd like to thank everyone who's offered their own thoughts – I wanted to explain where I was coming from when I put together that last of six abilities.

Strength: Of all the ability scores in D&D, this is the one with which I have the least issues. I believe a measure of a character's physical strength is much needed, especially in a game where melee combat plays such an important role. In addition, I want some way to measure how much weight a character can carry unaided and this seems as good a way to do it as any other I've seen.

Knowledge: I've long been unhappy with Intelligence as an ability. Most of the time, it's taken as a measure of how much a character knows. Look, for example, at its only explicit use in OD&D, namely, how many languages a character can speak. Given this, I thought it made some sense to shift the ability into something closer to education, both formal and informal.

Willpower: I think I now favor the term "Will," but the point remains that I dislike Wisdom even more than Intelligence. Wisdom has always been a weird, catch-all ability, simultaneously being the prime requisite for clerics and a gauge of a character's resistance to magic/mental attacks and his perceptiveness, among other things. It's a mess and I thought focuses on the mental fortitude aspect made the most sense, especially given that sha-Arthan has no cleric class.

Dexterity: I kept this one around mostly out of tradition. Its long association with missile combat seems reasonable and, being a Holmes baby, I can't help but imagine it as being important to the determination of individual initiative (even as I now favor simpler group initiative). Then there's the matter of defensive bonus introduced in Greyhawk about which I am ambivalent. If I had better ideas, I might change or eliminate this entirely.

Constitution: Part of me wants to roll this ability into Strength to create a new one, like Physique or something, but, again, the pull of tradition kept it around. I am conflicted about the hit point bonuses for high scores (since I prefer lower hit point totals overall), but I do like "withstand adversity" and its later developments.

Acumen: Empire of the Petal Throne has no Charisma score and that's probably influenced my thinking in replacing it (there's also the way other RPGs treat the matter). Instead, I opted for a broader ability that measures a character's ability to "read the room" to facilitate advantageous social interactions, whether to persuade, intimidate, or deceive. This is better suited to the kinds of campaigns I run, which include lots of diplomacy and intrigue.

This was my thinking when I wrote my post last week, but, as I said above, my thoughts remain in a state of flux. I have some vague notions now to cut down the abilities to five and associate them with sha-Arthan's elemental system and/or the saving throw categories. I also have equally vague notions to expand the list of abilities beyond six to include additional qualities I'd like to see quantified. It's all frankly a whirl at the moment and it may be some time yet before I've seen my way through to ordering my thoughts. For now, I continue to muse.

February 16, 2022

Retrospective: Gods of Hârn

As a general rule, I am very much opposed to the common practice among RPG hobbyists of buying products solely for reading purposes. I feel that game books should be bought with the intention that they be used in play, which explains why I buy so few new game books these days. I've only got so much free time in my life and, between refereeing two weekly campaigns and playing in a couple more, the odds of my making use of anything new I buy is limited. I realize this puts me at odds with a lot of my fellow gamers, who make a habit of picking up new gaming materials solely out of interest in their subject matter or because they're a collector to some degree.

As a general rule, I am very much opposed to the common practice among RPG hobbyists of buying products solely for reading purposes. I feel that game books should be bought with the intention that they be used in play, which explains why I buy so few new game books these days. I've only got so much free time in my life and, between refereeing two weekly campaigns and playing in a couple more, the odds of my making use of anything new I buy is limited. I realize this puts me at odds with a lot of my fellow gamers, who make a habit of picking up new gaming materials solely out of interest in their subject matter or because they're a collector to some degree. That said, I am a hypocrite on this matter when it comes to Hârn, a fantasy setting I've never used but whose support products I've nevertheless bought in surprising amounts. Everything I've purchased for Hârn is very well done, both in terms of content and presentation. There's an obvious love in these books that's almost infectious and I've often found myself picking them up over the years, despite my avowals not to do so. We all have our weak spots, I suppose, and the richly detailed fantasy world of Hârn is one of mine.

Of all the Hârn products I've bought (and never used) over the years, perhaps my favorite is Gods of Hárn. Originally published in 1985, the book is an overview of the ten gods of the setting's pantheon, along with information about the religions that worship them. For me, this is the most important part of what makes Gods of Hârn so special. There have been plenty of RPG books published about deities and divine beings, but few of them provide much in the way of useful information about the structure and activities of their mortal worshipers. Cults of Prax comes to mind, but, even there, the focus is more on the mythological role of the various gods of Glorantha than on the faiths of their followers.Each god in Gods of Hârn receives a description of his or her personality and role in the pantheon, but more detail is heaped on their church. The theological and social missions of the churches is discussed, along with information about their holy days, symbols, history, and clerical organization. Each of these categories is fleshed out in sufficient detail that both the player and referee would find them useful in play. Though there's plenty of detail in Gods of Hârn, the book doesn't luxuriate in detail for its own sake; nearly everything here is presented with the goal of enhancing play, which is particularly useful for players of priests or zealous devotees of a particular god. As a fan of Tékumel, believe me when I say that I adore setting detail. At the same time, I also recognize that there can be such as a thing as too much detail. I believe that Gods of Hârn strikes a good balance between leaving everything up to the referee's imagination and overloading him with needless minutiae.

There are no game statistics for the gods of Hârn's pantheon to be found here. The emphasis is more on the mortal side of religion, which is how it should be in my opinion. Throughout history, religions have played an important role, for good and ill, in human events. Often those roles were a direct consequence of the beliefs and structures of the religions themselves, a fact that Gods of Hârn clearly recognizes. The historical sections of the book detail many instances when one or more of the churches influenced events on Hârn and elsewhere. Likewise, the sections detailing their hierarchies and present activities provide plenty of scope for the referee to make religion matter in a way it sometimes doesn't in fantasy settings.

If nothing else, Gods of Hârn is a good model to emulate for creators and referees looking to present gods and religion in their settings and that's why I'm glad I own it, even though I've never played a campaign set on Hârn – at least that's what I keep telling myself.

February 15, 2022

White Dwarf: Issue #27

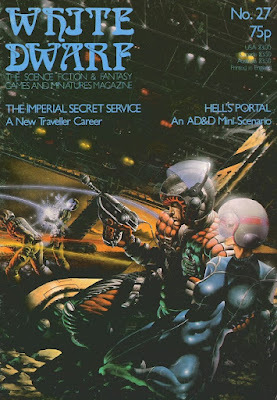

Issue #27 of White Dwarf (October/November 1981) features a science fictional cover by Allan Craddock, an artist who'd later do work on the Fighting Fantasy series. Ian Livingstone's editorial notes that 1982 "should be the year of monthly WD," thanks in no small part to the large number of submissions made to the magazine in answer to last month's appeal for them. The advent of monthly White Dwarf coincides precisely with my own awareness of the periodical, so I look forward to re-reading those issues with which I have contemporary acquaintance.

Issue #27 of White Dwarf (October/November 1981) features a science fictional cover by Allan Craddock, an artist who'd later do work on the Fighting Fantasy series. Ian Livingstone's editorial notes that 1982 "should be the year of monthly WD," thanks in no small part to the large number of submissions made to the magazine in answer to last month's appeal for them. The advent of monthly White Dwarf coincides precisely with my own awareness of the periodical, so I look forward to re-reading those issues with which I have contemporary acquaintance.

The issue begins with Part 3 of Roger Musson's "The Dungeon Architect." This month's installment discusses "The Populated Dungeon," by which Musson really means how and why the dungeon is the way it is. He starts, for example, with the "cybernetic dungeon" – an odd turn of phrase, to be sure, but one that refers to a computer-generated, which is to say, random dungeon. Such a dungeon is contrasted with the "ecological dungeon," whose layout and contents make sense according to naturalistic principles. Musson discusses other types of dungeons, too, like the "silly dungeon" and "improvised dungeon," among others. His overall point, though, is that the referee's approach to designing his dungeons has consequences for not just its final form but also how players might receive it. Like its predecessors, this installment is filled with excellent food for thought, even for experienced dungeon makers.

Robert McMahon offers up "The Imperial Secret Service," a new career for use with Traveller. This is an advanced career like those found in Mercenary or High Guard and covers the civilian secret agents of the Third Imperium. It's fine for what it is, but nothing special. Meanwhile, "Open Box" reviews the Deluxe Edition of Traveller (10 out of 10 for newcomers to the game; 4 out of 10 for old hands), Griffin Mountain (9 out of 10), Starfleet Battles (8 out of 10), IISS Ship Files (9 out of 10), Traders and Gunboats for Traveller (9 out of 10), and the GDW boardgame Asteroid (8 out of 10). That's a lot of science fiction gaming material! It's precisely because of White Dwarf's heavy SF focus that I relished any copies I came across in my youth, since that was my own preferred genre (and Traveller my favorite RPG).

Lewis Pulsipher's "An Introduction to Dungeons & Dragons" with its fifth part, this time dedicated to "Characterisation and Alignment." This is a much short part than the previous four and is mostly filled with the usual sorts of advice one might expect on the subject of "how to roleplay a character." The main points of interest (to me anyway) are that he recommends that the referee give experience to characters that are roleplayed well and in accordance with their stated alignments and that he suggest character decisions need not be done in "real time." That is, Pulsipher sees nothing wrong with a player who takes his time to determine what his character's actions might be rather than making a quick decision on the fly. I find this interesting in that it suggests Pulsipher doesn't see any necessity in a player's strongly identifying with his character; there's still some psychological "distance" between the two and this affects how a character is played.

Marcus L. Rowland's "The Dunegon at the End of the Universe" is a follow-up to last month's "DM's Guide to the Galaxy," which talks about D&D in space. This time, Rowland focuses on the intricacies of zero-G combat, ship-to-ship combat, and new spells and magic items that make sense within the context of outer space adventures. "Hell's Portal" by Will Stephenson is a short AD&D scenario about two groups – one the PCs, the other rival NPCs – attempting to find the arms and armor of a dead revolutionary in the ruins of a prison known as Hell's Portal. The competitive aspect of the adventure is an interesting one (and common in many White Dwarf scenarios). Also noteworthy is how many of the adventure's monsters are to be found in the Fiend Folio – British pride, no doubt!

"On the Cards" by Bob McWilliams is a short article recommending the creation and use of index cards to handle the details of weapon statistics in Traveller. "Summoners" is a new spellcasting class by Penelope Hill. As you might imagine, the class is based around the summoning of elementals, demons, devils, and other extraplanar beings. I actually like the idea behind classes like this, but I've long felt they tend to be too narrowly conceived to be generally useful and this article does little to change my mind.

"Fiend Folio" features five "near misses" – monsters that were almost included in the Fiend Folio but ultimately rejected, largely for matters of copyright. For example, there's the white ape from the Barsoom tales and the wirrn from the classic Doctor Who episode "The Ark in Space." How much one likes monsters of this sort depends, I think, on how tolerant one is of the blatant ripping off of ideas from other idea. For myself, I find them charming artifacts from a simpler time. Finally, "Treasure Chest" details seven new D&D spells, including a couple by Roger E. Moore.

White Dwarf's quality has, by this issue, acquired a degree of consistency that approaches that of other professional gaming magazines of the time. What sets it apart is the types of articles it publishes. They're generally a bit more off-beat than those in US periodicals and often focus on games, like Traveller, that don't get as many articles devoted to them in, say, Dragon or Different Worlds. That holds great attraction to someone such as myself, which is why I'm looking forward to the issues to come.

February 14, 2022

A Question re: Strength

If one uses, as OD&D, AD&D, and Empire of the Petal Throne do, a one-minute combat round, I think you're committing yourself to a broadly abstract approach to combat. As Gary Gygax explains in the Dungeon Masters Guide: "During a one-minute melee round many attacks are made, but some are mere feints, while some are blocked or parried."

If one understands combat in this way, I think it makes sense to avoid talking about "to hit" rolls, since, over the course of the round, there may be many attacks, some of them even landing a blow on an opponent. Rather, the combat roll determines whether or not any of those landed blows are strong enough to overcome the opponent's armor and deal damage. Thus, the "to hit" roll is really more like a "to damage" roll.

Consider how common it once was – and perhaps still is, for all I know – to criticize the way D&D uses armor class. Why, I recall being asked, does wearing plate mail make a character harder to hit than if he were wearing chainmail or leather armor? The answer is that it doesn't. Rather, certain types of armor make a character harder to damage, which is why I recommend dropping the use of phrases like "roll to hit" and the like.

All of this brings me to my question about Strength. Prior to Supplement I, a high Strength score conferred no mechanical benefits beyond a bonus to earned experience for fighting men. With the publication of Greyhawk, this changed. Now, a high Strength granted a bonus to "hit probability" and to damage. Given the understanding of the combat roll I propose above, does it make any sense for a high Strength score to do both?

A bonus to the chance to deal damage (called "hit probability") makes sense to me, since what that really indicates is an increase in the likelihood that a character can land a hit solid enough to harm his opponent. I find it reasonable that a high Strength might assist in this. Why, then, a bonus to damage dealt as well? Isn't that "doubling up" on the Strength's role in combat or am I overthinking this, as I often do?

I hope I've explained myself clearly enough so that my question is intelligible. If not, I'll do my best to clarify my position in the comments.

February 13, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Phoenix on the Sword

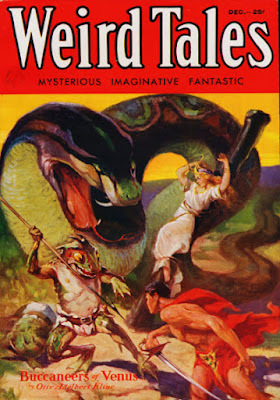

While writing in this series, I realized that I had somehow never written a post about "The Phoenix on the Sword," the very first published yarn of Conan the Cimmerian," and I resolved to rectify the matter as soon as possible. As is well-known, "The Phoenix on the Sword" is a reworking of another story, "By This Axe I Rule!," which Howard wrote for the character Kull of Atlantis in 1929. Twice rejected at the time of its writing, REH set the tale aside for several years before he turned it into the debut of Conan, resulting in its publication in the December 1932 issue of Weird Tales.

While writing in this series, I realized that I had somehow never written a post about "The Phoenix on the Sword," the very first published yarn of Conan the Cimmerian," and I resolved to rectify the matter as soon as possible. As is well-known, "The Phoenix on the Sword" is a reworking of another story, "By This Axe I Rule!," which Howard wrote for the character Kull of Atlantis in 1929. Twice rejected at the time of its writing, REH set the tale aside for several years before he turned it into the debut of Conan, resulting in its publication in the December 1932 issue of Weird Tales.Like its immediate sequel, "The Scarlet Citadel," "The Phoenix on the Sword" is a story of Conan after he has become king of Aquilonia. Indeed, there's a remarkable degree of similarity between the two stories, at least when it comes to their overall plots. In both, a conspiracy consisting of noblemen aided by a sorcerer works to overthrow Conan and place one of their own on the throne. There the resemblance ends.

"The Phoenix on the Sword" is likely the most quoted tale of Conan, beginning as it does with the following:

"KNOW, oh prince, that between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities, and the years of the rise of the Sons of Aryas, there was an Age undreamed of, when shining kingdoms lay spread across the world like blue mantles beneath the stars—Nemedia, Ophir, Brythunia, Hyperborea, Zamora with its dark-haired women and towers of spider-haunted mystery, Zingara with its chivalry, Koth that bordered on the pastoral lands of Shem, Stygia with its shadow-guarded tombs, Hyrkania whose riders wore steel and silk and gold. But the proudest kingdom of the world was Aquilonia, reigning supreme in the dreaming west. Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen- eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet."—The Nemedian Chronicles

Whatever else one can say about the story – or indeed about Robert E. Howard's work in general – I don't think there can be any question that the excerpt above is a remarkably evocative bit of writing. With just a handful of sentences, Howard firmly establishes his setting, its mood, and his protagonist. It's an amazing bit of literary economy and I can't help but be envious of how much he did with so few words.

After this, the reader is introduced first to the outlaw Ascalante and then to the Rebel Four who have "summoned [him] from the southern desert." The Four are

Volmana, the dwarfish count of Karaban; Gromel, the giant commander of the Black Legion; Dion, the fat baron of Attalus; Rinaldo, the hare-brained minstrel

Each of the Rebel Four has his own reasons for wanting to see Conan, "a red-handed, rough-footed barbarian who came out of the north to plunder a civilized land," dethroned, but all are united in wanting to see it done by any means necessary. That's why they have turned Ascalante, a ruthless bandit with a reputation for achieving what he sets out to do. Unbeknownst to them, Ascalante has his own plans.

As for me – well, a few months ago I had lost all ambition but to raid the caravans for the rest of my life; now old dreams stir. Conan will die; Dion will mount the throne. Then he, too, will die. One by one, all who oppose me will die – by fire, or steel, or those deadly wines you know so well how to brew. Ascalante, king of Aquilonia! How do you like the sound of it?

The outlaw boasts of his plan to his slave, a Stygian who bemoans his own fate.

"There was a time," he said with unconcealed bitterness, "when I, too, had my ambitions, beside which yours seem tawdry and childish. To what a state I have fallen! My old-time peers and rivals would stare indeed could they see Thoth-amon of the Ring serving as the slave of an outlander and an outlaw at that; and aiding the petty ambitions of barons and kings!"

This is one and only direct appearance of the wizard Thoth-amon in the Howardian canon. Yet, so memorable is this appearance, that it left a lasting impression on the minds of many pasticheurs, like L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter, who then concocted the idea that he was somehow Conan's arch-nemesis. The Marvel Conan comics of Roy Thomas perpetuated this notion, from which it passed into the imaginations of many others.

While Ascalante and the Rebel Four plot against him, Conan is unhappily reflecting on his current situation as a barbarian ruling a civilized kingdom.

"When I overthrew the old dynasty," he continued, speaking with the easy familiarity which existed only between the Poitainian and himself, "it was easy enough, though it seemed bitter hard at the time. Looking back now over the wild path I followed, all those days of toil, intrigue, slaughter and tribulation seem like a dream.

"I did not dream far enough, Prospero. When King Numedides lay dead at my feet and I tore the crown from his gory head and set it on my own, I had reached the ultimate border of my dreams. I had prepared myself to take the crown, not to hold it. In the old free days all I wanted was a sharp sword and a straight path to my enemies. Now no paths are straight and my sword is useless.

Conan's last statement sums up well the plot of "The Phoenix on the Sword" and why it's so compelling. Conan is a good king; he rules Aquilonia and its people more fairly than his predecessor. Yet, he is a foreigner and a barbarian at that. Many of his subjects do not accept him as their ruler and now foolishly recall the tyrant Numedides with misplaced fondness. The conspiracy of the Rebel Four is built, at least in part, on Conan's lack of acceptance by a populace who do not fully understand how lucky they are to have this barbarian rule rather than one of their own. Conan knows this and laments it, just as he laments the way that his crown binds him and keeps him from the freedom he once enjoyed. This is powerful stuff and near-perfect grist for the pulp fantasy mill. It's not a perfect tale by any means, but it's well worth a read, if you've never had the chance to do so before.

February 11, 2022

An Aside re: Charisma

From Chivalry & Sorcery (1977), p. 6:

CHARISMA

Charisma is the ability of a character to arouse popular loyalty and enthusiasm by the force of his own personality and reflects his ability to command men in battle. It is a natural talent growing out of other characteristics. To find a character's basic Charisma, add his Intelligence, Wisdom, Appearance, Bardic Voice, and Dexterity scores, and divide the total by 5. If he is over 6 feet tall, add 1 point. Add all bonuses to the total.

From RuneQuest (1978), p. 12:

Charisma is a nebulous quality, and increasing or decreasing it is often up to the referee's whimsy. However, the following instances can have some effect:

a. Each 25% skill with Oratory learned increases a character's CHA by 1 point. Maximum of 4 points.

b. Each 25% increase in the use of one's main weapon (after 50%) adds 1 point. No limit to points.

c. Possession of good, showy, magical objects raises CHA by 1 point. Just 1 point is gained here. It does not matter if the character has just one or one hundred showy items.

d. Successful leadership of an expedition (i.e., the loss/gain ratio is satisfactory) can add a point to the character's CHA. A character may roll his CHA as a percent or lower for a gain, or the Referee may have some other criterion.

e. Unsuccessful leadership can lose CHA. A really disastrous expedition can cause the leader to have to make his CHA as a percentage or lose 1 to 3 CHA points.

February 10, 2022

Barrett's Raiders

Known as Barrett's Raiders, the campaign focuses on eight characters – seven Americans and one Russian POW – trying to make their way through central Poland in the aftermath of the disastrous Battle of Kalisz (July 9–18, 2000). The battle was the last big push by NATO forces against the Warsaw Pact and it ended terribly for the West. During the ensuing chaos, the characters fled south in a HMMWV and LAV-25, making their way to a forest between Kepno and Złoczew before continuing southeast to the area between Kluczbork, Praszka, and Krzepice.

The characters in the group consist of:Lieutenant Colonel Joseph "JD" OrlowskiSergeant Andrew Alexander "Double A" McLeodSergeant Hiram "Dutch" EvertsSergeant Tom CodyStaff Sergeant John J. "Headshot" MillerSergeant First Class Jess "Cowpoke" GartmannMichael (a civilian intelligence agent who'd been posing as a Pole)Dr Vadim Konosev (Russian captured before the Battle of Kalisz)Though we've been playing for two months now, only three days of game time have passed. The characters have been doing their best to stay hidden and avoid conflict with Warsaw Pact forces still in the area. With the exception of an encounter with some scouts of the Soviet 129th Motorized Rifle Division, they've largely been successful, though it's increasingly clear that their luck can only last so long.

The characters in the group consist of:Lieutenant Colonel Joseph "JD" OrlowskiSergeant Andrew Alexander "Double A" McLeodSergeant Hiram "Dutch" EvertsSergeant Tom CodyStaff Sergeant John J. "Headshot" MillerSergeant First Class Jess "Cowpoke" GartmannMichael (a civilian intelligence agent who'd been posing as a Pole)Dr Vadim Konosev (Russian captured before the Battle of Kalisz)Though we've been playing for two months now, only three days of game time have passed. The characters have been doing their best to stay hidden and avoid conflict with Warsaw Pact forces still in the area. With the exception of an encounter with some scouts of the Soviet 129th Motorized Rifle Division, they've largely been successful, though it's increasingly clear that their luck can only last so long. A map captured from the scouts suggests that the Soviets have their own internal problems. Many of their troops have deserted and turned to marauding. The map also seems to imply a concentration of US forces in the town of Dobrodzień, but there's no way of knowing if it's true. Moreover, given the general breakdown in unit cohesion and discipline on all sides, is it any safer to hook up with even their fellow Americans? These are the questions that occupy Lt. Col. Orlowski as he tries to keep this little band alive in unfriendly territory.

Like the House of Worms campaign, I'll write occasional posts about Barrett's Raiders and how it's unfolding. That's in addition to my thoughts about the new Twilight: 2000 rules and my experiences using them. Thus far, we've been having fun and I have high hopes that the campaign will be a long one (though perhaps not as long as House of Worms – few are!).

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers