James Maliszewski's Blog, page 114

March 6, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: Atlantis: The Antediluvian World

A brief caveat: Atlantis: The Antediluvian World is not a work of fiction – at least not of an intentional kind. At the time it was published (1882), it was presented as speculative archeology, however dubious that claim might have been, even by the standards of its own time. More to the point, its author, Ignatius L. Donnelly, did not believe he was writing fiction but rather that he was advancing "several distinct and novel propositions" regarding "an Atlantic continent … known to the ancient world as Atlantis." He believed this so strongly that he continued to advance his theses for the remainder of his life, writing a sequel in 1883 and inspiring countless other writers in the ensuing decades.

A brief caveat: Atlantis: The Antediluvian World is not a work of fiction – at least not of an intentional kind. At the time it was published (1882), it was presented as speculative archeology, however dubious that claim might have been, even by the standards of its own time. More to the point, its author, Ignatius L. Donnelly, did not believe he was writing fiction but rather that he was advancing "several distinct and novel propositions" regarding "an Atlantic continent … known to the ancient world as Atlantis." He believed this so strongly that he continued to advance his theses for the remainder of his life, writing a sequel in 1883 and inspiring countless other writers in the ensuing decades. It's largely on this basis that I'm including it as this week's Pulp Fantasy Library post. Considered purely in terms of its influence on later fiction, Atlantis: The Antediluvian World is an important product of human imagination and creativity, easily on par with the avowedly literary efforts of H.P. Lovecraft, or J.R.R. Tolkien. Indeed, if you've ever read a story involving Atlantis, whether it be Clark Ashton Smith's tales of Poseidonis, Robert E. Howard's Kull yarns, or even the adventures of Aquaman, to cite just a few, you owe a debt to Ignatius Donnelly and his obsession with proving that Atlantis was not only real but "the region where man first rose from a state of barbarism to civilization."

Donnelly himself is a fascinating fellow, in the way that only men from the past seem to be. Born in Philadelphia in 1831, he became a lawyer and moved to the Minnesota territory, where he attempted to found a cooperative farm and utopian community with several others. Though the farm failed, leaving him in debt, Donnelly managed to use his rhetorical skills to become Minnesota's second lieutenant governor after statehood. Later, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and to seats in both houses of Minnesota's state legislature. As a politician, he advocated for women's suffrage, a progressive income tax, and an eight-hour workday, among many other causes radical for their time. And, of course, he was also an advocate of the belief that Atlantis "is not a fable, as has been long supposed, but veritable history." Like Whitman, Donnelly contained multitudes.

Atlantis is a lengthy and ponderous book, divided into five parts, each consisting of six or more chapters. The tome begins with a chapter in which Donnelly lays out "the purpose of the book" by asserting the following theses:

1. That there once existed in the Atlantic Ocean, opposite the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea, a large island, which was the remnant of an Atlantic continent, and known to the ancient world as Atlantis.

2. That the description of this island given by Plato is not, as has been long supposed, fable, but veritable history.

3. That Atlantis was the region where man first rose from a state of barbarism to civilization.

4. That it became, in the course of ages, a populous and mighty nation, from whose overflowings the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, the Mississippi River, the Amazon, the Pacific coast of South America, the Mediterranean, the west coast of Europe and Africa, the Baltic, the Black Sea, and the Caspian were populated by civilized nations.

5. That it was the true Antediluvian world; the Garden of Eden; the Gardens of the Hesperides; the Elysian Fields; the Gardens of Alcinous; the Mesomphalos; the Olympos; the Asgard of the traditions of the ancient nations; representing a universal memory of a great land, where early mankind dwelt for ages in peace and happiness.

6. That the gods and goddesses of the ancient Greeks, the Phoenicians, the Hindoos, and the Scandinavians were simply the kings, queens, and heroes of Atlantis; and the acts attributed to them in mythology are a confused recollection of real historical events.

7. That the mythology of Egypt and Peru represented the original religion of Atlantis, which was sun-worship.

8. That the oldest colony formed by the Atlanteans was probably in Egypt, whose civilization was a reproduction of that of the Atlantic island.

9. That the implements of the "Bronze Age" of Europe were derived from Atlantis. The Atlanteans were also the first manufacturers of iron.

10. That the Phoenician alphabet, parent of all the European alphabets, was derived from an Atlantis alphabet, which was also conveyed from Atlantis to the Mayas of Central America.

11. That Atlantis was the original seat of the Aryan or Indo-European family of nations, as well as of the Semitic peoples, and possibly also of the Turanian races.

12. That Atlantis perished in a terrible convulsion of nature, in which the whole island sunk into the ocean, with nearly all its inhabitants.

13. That a few persons escaped in ships and on rafts, and, carried to the nations east and west the tidings of the appalling catastrophe, which has survived to our own time in the Flood and Deluge legends of the different nations of the old and new worlds.

To anyone with even the slightest interest in the subject of Atlantis – or the decades of pulp fantasy musings on the subject – none of these propositions is the least bit surprising. At the time, though, they were bold and original, if not at all historically well-founded. Atlantis was a success for Donnelly and its ideas were disseminated widely, so much so that they now form an important substrate of both popular culture and esoteric beliefs.

Growing up, the mother of two friends of mine, with whom I first began playing RPGs, had an extensive library of books that, at the time, we called "New Age." Among them was a copy of Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, alongside the works of authors inspired by it, like Edgar "The Sleep Prophet" Cayce and various Theosophists. I'd sometimes take the books off her shelves and peruse them, looking for interesting sections that might inspire D&D adventures. Even as a kid, I found most them more than a little ridiculous, but Donnelly's book held my attention, perhaps because of its author's self-seriousness and obvious enthusiasm for the "revelations" he is imparting to his readers. It's not difficult to see why it caused a stir in its day or why its central theory, however implausible, continues to maintain a hold over the popular imagination almost a hundred and fifty years later.

March 4, 2022

House of Worms Humor

Tékumel, despite its outward appearance, is actually a science fiction setting – a "secret sci-fi" setting, as I sometimes call it. Clarke's Third Law is in full effect and pretty much everything that is seemingly fantastical has a rational explanation (for a given definition of "rational," admittedly). I've leaned into this quite heavily over the last few years. I decided that the Achgé Peninsula was a storehouse of lost and forgotten ruins of the Ancients, many of which contained some remarkable pieces of "sufficiently advanced" technology. Likewise, the culture of the native Naqsái (and that of their west coast cousins, the Hnákho) owed a lot to the presence of these technologies, however misunderstood they are in the current age.

Tékumel, despite its outward appearance, is actually a science fiction setting – a "secret sci-fi" setting, as I sometimes call it. Clarke's Third Law is in full effect and pretty much everything that is seemingly fantastical has a rational explanation (for a given definition of "rational," admittedly). I've leaned into this quite heavily over the last few years. I decided that the Achgé Peninsula was a storehouse of lost and forgotten ruins of the Ancients, many of which contained some remarkable pieces of "sufficiently advanced" technology. Likewise, the culture of the native Naqsái (and that of their west coast cousins, the Hnákho) owed a lot to the presence of these technologies, however misunderstood they are in the current age.As a result of events almost two years prior in game-time, the characters inadvertently released three malevolent otherplanar entities from their prison. They were then bidden by the prison's equally otherplanar guardian to find and defeat them. One has was beaten at the Temple of the Ages to the west of the city-state of Mánmikel. The location of the second is now known: occupying the body of a Livyáni woman in the colony of Nuróab (in a strange parallel to what happened to Aíthfo) and causing havoc throughout the Peninsula as a result. The location of the third entity remains unknown.

Currently, the characters are searching for a transplanar energy siphon, a type of Ancient technology known colloquially as a "god trap." Their researches suggest that such technology might be found on an island old texts call the Isle of Sweet Gentility but that the local Naqsái call the Isle of Ghosts. The island is many weeks travel westward along the coast of the Peninsula in the direction of the Hnákho. Part way through their sea journey, they stopped to re-supply (among other things) at the city-state of Chámara.

The people of Chámara have two great loves: trade and bureaucracy. The last couple of sessions have focused on the characters' attempts to wade through the city's seemingly endless procedures for doing pretty much everything, hence the image above, created by a player, who found the temporary derailment of the characters' goals amusing. Truth be told, these sessions have been amusing, especially as the characters grapple with the fact that, unlike the Tsolyáni, the Chámarans don't seem to go in for bribes and other forms of peculation. The rules are the rules and, if they want their supplies, they'll need to put up with all the interrogations, forms, and waiting in queues that the Chámarans throw at them.

March 3, 2022

Copper Anniversary

In the world of Tékumel, copper is the sacred metal of Sárku, the Five-Headed Lord of Worms and Master of the Undead, to whom the House of Worms clan of my ongoing Empire of the Petal Throne campaign is dedicated. Copper is also, according to the American reckoning of these things, the appropriate gift for commemorating a seventh anniversary. I was struck by this happy coincidence as I pondered the fact that today marks seven years since the House of Worms campaign began.

In the world of Tékumel, copper is the sacred metal of Sárku, the Five-Headed Lord of Worms and Master of the Undead, to whom the House of Worms clan of my ongoing Empire of the Petal Throne campaign is dedicated. Copper is also, according to the American reckoning of these things, the appropriate gift for commemorating a seventh anniversary. I was struck by this happy coincidence as I pondered the fact that today marks seven years since the House of Worms campaign began.This is probably the single longest continuous roleplaying campaign I have ever refereed. Its length alone is remarkable and worthy of celebration, especially in this day and age, when long campaigns are increasingly uncommon. What's even more special, I think, are the friendships formed and strengthened through our weekly meetings.

This campaign launched at the start of March 2015 with six players, only one of whom I knew very well. The others were a mix of people with whom I'd had brief interactions online or whom I did not know at all, even by reputation. I had no expectation, when we began, that the campaign would last even a month, let alone seven years. I was simply grateful that six people were willing to take a chance on gaming in the weird world of Tékumel with me.

As it turned out, our little band got on well with one another and, by the time we reached our first anniversary, it was pretty clear that this campaign was something special. Only four of the original six players made it to the first anniversary, but soon others joined to fill the ranks of the group. The number of active players has fluctuated a bit over the years, but it's been quite stable at seven for at least the past two, maybe longer – one of the dangers of such a long campaign is forgetfulness, I'm afraid!

The player characters began the campaign in the city of Sokátis, at the eastern edge of the Empire of Tsolyánu. In the years since, they've traveled to the neighboring kingdom of Salarvyá, then to Yán Kór, Sa'á Allaqí, the Dry Bay of Ssu'ú, and back to Sokátis before setting off to the Achgé Peninsula of the unknown Southern Continent. They've ventured into innumerable underworlds, done battle with the dreaded Ssú and Shunned Ones, traveled for months by sea, and visited an alternate version of Tékumel, among too many other exploits to mention. The characters have also married, advanced within the civil and religious hierarchies, become embroiled in imperial politics, and explored lands no Tsolyáni has ever visited. It's been quite the ride – and it's nowhere close to being over.

I could go on at some length about the details of this amazing campaign and some of you might even find them interesting. Looking back on it, though, what really sticks with me are the lovely people with whom I've had the honor of roleplaying each week for so many years. I've made a great many friends through this hobby and indeed consider gaming with friends to be one of the great joys of life. By that standard, the House of Worms campaign stands very tall. It's a testament to everything that's great about this pastime we share. It's my sincere wish that everyone reading this has had at least one experience of the hobby like this or will have one in the future.

What a long, strange trip it's been! Thank you, my friends, for the untold hours of enjoyment you have given me. Here's to many years more.

(You can read an extensive reflection on the past seven years of the campaign here, written by one of the four players who's been here since the beginning.)

Strange Thoughts on Experience Bonuses

Supplement I changed all this, first by introducing the thief class, whose prime requisite was Dexterity, and second by beefing up the mechanical benefits of most of the other abilities (the main exception being Wisdom, which remains solely "an experience booster for clerics," in the words of Gygax). These changes, which were carried on and even expanded by later versions of the game, began the process that ended with the claim, in the AD&D Players Handbook, that it is "usually essential to the character's survival to be exceptional (with a rating of 15 or above) in no fewer than two ability characteristics."

After lots of thought on the matter, I have made some measure of peace with the idea that ability scores should be mechanically important. If not, what's the point of even generating them? However, I continue to worry that, by making high scores in abilities mechanically beneficial, there will come to be an expectation that, as in AD&D, most characters must have high ability scores. In that case, we get a variation on the previous question: what's the point of generating ability scores at all if every character needs to have high ones?

The question becomes even more relevant when one considers that, as written, characters with high scores in their prime requisite not only reap immediate mechanical benefits from those scores (hit and damage bonuses, higher hit points, etc.), they also advance faster in their chosen class, thanks to the bonus to earned experience. To my mind, this makes high ability scores so attractive that I wonder why any player would not deem a character with any sub-optimal abilities "hopeless" and roll up a new one. Consider, too, the increasingly absurd lengths to which AD&D went to ensure that all player characters were exceptional in their ability scores.

As is so often the case these days, I find myself taking inspiration from Chaosium's RuneQuest. In RQ, there are mechanical benefits to having a low score in at least one ability. I very much like that because that benefit comes at a cost; there's a trade-off between two clear mechanical goods. I'd love to see something similar in D&D and derivative games, something that provides some incentive not to have high scores in every ability.

That's why I have a strange idea: what if, instead of granting an experience bonus for high ability scores, one granted them for low scores? On some level, this makes intuitive sense to me. Would not a character whose native abilities were already exceptional learn less from his experiences than a character whose abilities were below average? Further, I can't help but feel that granting an XP bonus to a high score, which already grants clear mechanical benefits, is gilding the lily, so to speak. If the goal is to keep the random rolling ability scores and encourage players to keep the scores rolled, does it not make sense to provide a "consolation prize" to low scores?

I am sure there are problems with this idea and, if so, I expect my readers to point them out in the comments. From my current vantage point, though, I think this is something to be explored, both from a purely game perspective and from the point of view of learning through experience.

March 2, 2022

Monsters, Monsters, and More Monsters!

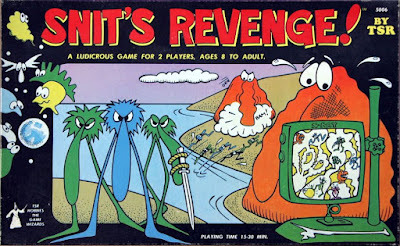

Retrospective: Snit's Revenge

Last month, I wrote a post in which I briefly sang the praises of Tom Wham, whom I called an underappreciated game designer. When I wrote that, I cited a few examples of his designs that I remember playing in my youth and was surprised to discover that I had never, in the more than 270 retrospective posts I've made over the years, written one about Snit's Revenge. This surprised me multiple reasons, not least of which being that I probably played Snit's Revenge almost as often as I played The Awful Green Things from Outer Space (my favorite Tom Wham game). Still, it was strangely pleasing for a TSR fanboy like myself to discover I still had a few more memories left to mine for blog content.

Last month, I wrote a post in which I briefly sang the praises of Tom Wham, whom I called an underappreciated game designer. When I wrote that, I cited a few examples of his designs that I remember playing in my youth and was surprised to discover that I had never, in the more than 270 retrospective posts I've made over the years, written one about Snit's Revenge. This surprised me multiple reasons, not least of which being that I probably played Snit's Revenge almost as often as I played The Awful Green Things from Outer Space (my favorite Tom Wham game). Still, it was strangely pleasing for a TSR fanboy like myself to discover I still had a few more memories left to mine for blog content.I first encountered Snit's Revenge in its 1980 boxed set form, which I purchased at Kay-Bee Toys sometime in 1981 or '82. This is actually the third version to appear under the auspices of TSR, the first being in the pages of Dragon magazine (December 1977) and the second a smaller boxed game (1978) similar in size to the original release of Dungeon! The 1980 version had pretty good production values and generally looked more like the kind of "family boardgame" published by Parker Brothers or Milton-Bradley, which makes sense, given TSR's ambitions to broaden their audience beyond the teenagers and college students who were D&D's primary customers.

Like many Tom Wham games, Snit's Revenge is a two-player game, with one of the players taking the role of the titular Snits and the other their mortal enemies the Bolotomi – or rather the immune system of a single Bolotomus, as it attempts to fend off an infestation (infection?) of Snits. Wham amusingly provides a backstory for this situation in the form of a comic in which he shows how a deity, Embraz the Bulbous, created a world to alleviate his boredom. Eventually, Embraz seeks the aid of his fellow gods to make "something new" for the world he created, leading to the creation of the immense Bolotomi and the tiny Snits. The Bolotomi enjoyed nothing more than smashing Snits, but the Snits were gifted with the ability to reproduce quickly, which enabled them to enter the bodies of Bolotomi and attempt to destroy their "spark of life" from within.

If this all sounds silly and bizarre, it is, but what else would you expect from a Tom Wham game? Basic gameplay is quite simple, with the Snit player attempting to destroy the internal organs of the Bolotomus, one of which holds the aforementioned "spark of life." Destruction of that organ results in the death of the Bolotomus and victory for the Snit player. The Bolotomus player attempts to mount a defense against the Snits with Snorgs, which act like leukocytes in the human body. In the advanced version of the game, the Bolotomus player has additional defenses at his disposal, such as Makums and Runnungitms, while the Snit player Supersnits, which are hardier and generally more dangerous. In both versions of the game, the main advantage of the Snit player is numbers; indeed, he does not need to reveal just how many Snits he has in his invasion force and this uncertainty hampers the decisions of the Bolotomus player.

Snit's Revenge has a bit less replayability than The Awful Green Things in my experience, owing to a smaller board and fewer random elements. Likewise, it's unconventional subject matter is perhaps not quite as appealing as the straightforward B-movie scenario of The Awful Green Things. Even so, my friends and I had fun with it. A complete game could be played in no more than 30 minutes and it wasn't uncommon to do so in even less time. That made it perfect for playing while we waited for our RPG group to assemble in someone's basement.

March 1, 2022

Days of Future Past

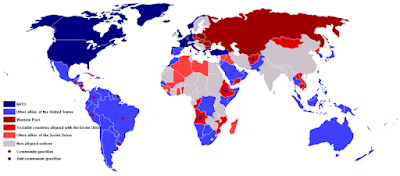

I've been refereeing a Twilight: 2000 campaign using the new edition recently released by Free League. The campaign began in early December and is played weekly with a group of seven players, who've elected to call their little band (for reasons that are largely the result of an in-joke and thus have no deeper meaning) Barrett's Raiders. I've been having a lot of fun with the campaign thus far, though I don't yet feel fully proficient in the new rules, particularly those for combat, which are quite different than those in the 1984 edition of the game with which I am most familiar. That's to be expected; I am sure, after a few more months of play, that I'll be sufficiently acclimatized to the new rules that I'll be able to referee our sessions almost effortlessly.

I've been refereeing a Twilight: 2000 campaign using the new edition recently released by Free League. The campaign began in early December and is played weekly with a group of seven players, who've elected to call their little band (for reasons that are largely the result of an in-joke and thus have no deeper meaning) Barrett's Raiders. I've been having a lot of fun with the campaign thus far, though I don't yet feel fully proficient in the new rules, particularly those for combat, which are quite different than those in the 1984 edition of the game with which I am most familiar. That's to be expected; I am sure, after a few more months of play, that I'll be sufficiently acclimatized to the new rules that I'll be able to referee our sessions almost effortlessly.At the time of its original release, Twilight: 2000 was set sixteen years in the future. The good folks at GDW, being thoughtful and intelligent men – in addition to being well-read on matters military – did, I think, a pretty job of imagining a limited nuclear conflict scenario between NATO and the Warsaw Pact that was both plausible and, above all, playable, given then-current information. As we now know, the real world rather quickly was at odds with this scenario and, despite the best efforts of GDW to tweak it to take into account the unfolding of history, Twilight: 2000 was soon relegated to realm of alternate history.

Now, like a lot of nerds, I have a great fondness for alternate histories. Yet, for some reason I can't fully explain, I prefer that the points of divergence in my alternate histories be well in the past. Consequently, I had a difficult time continuing to play Twilight: 2000 in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union. An alternate World War II? Sure! An alternate conclusion to the Cold War? No – at least not in the 1990s or even early 2000s. Again, I don't pretend this prejudice on my part is any way rational, only that it's one I feel quite strongly, hence my putting Twilight: 2000 on the shelf for several decades.

By the time Free League announced they were producing a new edition, I had already become much more comfortable with the idea of looking on the game as set in an alternate history. As luck would have it, I was already in the midst of re-reading all my old GDW supplements when I heard the news of a new edition, which I took as a sign from the gaming gods that I ought to start up a campaign on its release. And so I did, as I've explained before.

Free League's version of the game uses an alternate history, of course, but it's an alternate history where the point of divergence is in the early 1990s. The coup attempt against Gorbachev in 1991 succeeds and the USSR emerges revitalized and ready to launch the Sino-Soviet War in 1995. I understand why they went this route, but I don't much like it myself, preferring instead the 1984 timeline, which (for obvious reasons) does not include Gorbachev's rise to power at all. Quite simply, I prefer to referee a campaign set in the year 2000 as imagined by people living in 1984 than in one that shares the real world's history up until 1991. Once more, I say: this is not a wholly rational preference on my part but its one that makes it easier for me to run a game set in the aftermath of an alternate history World War III.

This preference has many consequences, as I keep reminding my players. So many aspects of the real 1990s, especially technological ones, do not exist in my Twilight: 2000 campaign. For example, computer technology is not as advanced as in our world. Likewise, the Internet, while it exists as ARPANET, has not had a significant impact on society, due to its limited user base. On the other hand, some experimental technologies from 1984, like the H&K G11 weapons system, entered service in this alternate history and are now more widely used. The same is true for a number of other bits of military hardware that, in our world, were never adopted.

One of the reasons I enjoy alternate histories is the consideration of paths not taken. This campaign has only just begun and the player characters have not yet got very far from their starting point – indeed, only four days have passed in-game – but I can already begin to see the seeds from which further historical divergences might grow. It's my hope, as the months roll on, that the characters will have the chance to influence events not just in southwestern Poland but perhaps farther afield. My dream is that, eventually, those that survive might make it back home to the USA and help rebuild it in the aftermath of the war. For now, I'm enjoying the ride, wherever it goes.

White Dwarf: Issue #29

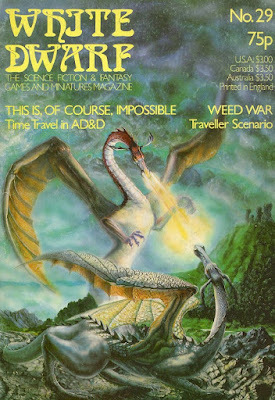

Issue #29 of White Dwarf (February/March 1982) features a cover illustration by Andrew George, depicting two dragons fighting with one another. It's a surprisingly mundane piece of artwork for WD in my opinion, but it's nevertheless well done. Inside, Ian Livingstone explains the origin of the magazine's name and it's as straight forward as one might have guessed. Since the then-nameless periodical was to cover both fantasy and science fiction, any proposed name would have "to reflect both those topics." He then explains that "a dwarf is a well-known fantasy character, and a white dwarf is a small, high density star. And that's all there is to it. Simple really when you think about it."

Issue #29 of White Dwarf (February/March 1982) features a cover illustration by Andrew George, depicting two dragons fighting with one another. It's a surprisingly mundane piece of artwork for WD in my opinion, but it's nevertheless well done. Inside, Ian Livingstone explains the origin of the magazine's name and it's as straight forward as one might have guessed. Since the then-nameless periodical was to cover both fantasy and science fiction, any proposed name would have "to reflect both those topics." He then explains that "a dwarf is a well-known fantasy character, and a white dwarf is a small, high density star. And that's all there is to it. Simple really when you think about it."

The issue starts with a bang. Paul Vernon presents the first part of a multi-issue series entitled "Designing a Quasi-Medieval Society for D&D." The inaugural article focuses on "The Economy – Workers and Craftsmen." Over the course of three, densely-packed pages – in the tiny font I so strongly associate with White Dwarf – Vernon covers a wide range of economic topics, from occupations, apprenticeships, wages, quality of goods, and more. In doing so, he attempts to stay true as possible to both history and to the established rules of (A)D&D, hence the use of "quasi-medieval" in the title. All in all, I think he does a good job of what he sets out to do, though at times I found his discussions tedious (as I usually do in works of this sort). On the other hand, the simple fact that he raises questions about the wider societal implications of D&D's rules is worthy of praise.

"Lucky Eddi" by Oliver Dickinson is a work of fiction set in the city of New Pavis in RuneQuest's setting of Glorantha. I'm generally not a fan of "game fiction," but I make an exception for Dickinson's work, which is delightful. His stories, of which this is the first, depict Glorantha from the perspective of the rogues and ne'er-do-wells of New Pavis. The style is reminiscent of the works of Damon Runyon and is a lot of fun, especially if you don't mind your version to be much less self-serious than the setting has become over the years. Reading Dickinson's stories in White Dwarf were one of the reasons I started to re-evaluate my previous prejudices about RuneQuest. Re-reading the first installment in this issue was a joy.

"Open Box" reviews four interesting products, starting with GDW's Fifth Frontier War, which earns a rating of 8 out of 10. The licensed Traveller supplement SORAG (published by Paranoia Press) receives an even higher rating of 9 out of 10. Barbarian Prince by Dwarfstar is a favorite of mine, so I was glad to see that the reviewer thought quite highly of it as well (8 out of 10). The final review was of Chaosium's Stormbringer, which only received a 7 out of 10 – still a solid rating but not as good as I would have expected in the pages of WD. The main complaint of the reviewer, Murray Writtle, is that the game is not suitable for long-term campaign play, as "inglorious death" was all too common. I think that's a fair comment, though I'm not sure I'd consider it a flaw in the game.

Dryden Badenoch's "The Mudskipper" is a 100-ton multi-terrain vehicle for use with Traveller. It's a clever idea and nicely presented, complete with a map of its interior. "This Is, Of Course, Impossible" by Marcus L. Rowland is an article outlining the possibilities for "Time Travel in AD&D." Over the course of three pages, Rowland nicely discusses the topic at hand. He starts off with an overview of various interpretations of time and how each views divergences. He then moves on to methods of time travel, from magical to technological, before discussing the use of time travel in adventures and campaigns. Rowland even includes a bibliography of stories touching on the subject. All in all, it's very well done.

S. McIntyre's "Weed War" is a Ttraveller scenario set on a world in the Spinward Marches. The scenario concerns a struggle between various interests for control of a native species of seaweed that is useful in the production of certain pharmaceuticals. I like the adventure well enough, though the general set-up is a well-worn one in Traveller. Roger E. Moore described "Gray and Sylvan Elves" as a PC race for use with AD&D and Bob Lock does the same for "The Brownie." Fuddy-duddy that I am, neither of these articles thrilled me; I'm generally of the opinion that D&D should have fewer race options, not more. "Fiend Factory" offers up five monsters from "The Light Desert." None of them really grabbed my attention, but the artwork accompanying the article is rather good. Finally, we get a new approach to "Amulets & Talismans" in D&D from Lewis Pulsipher. In his interpretation, the items in question are more disposable and can be made by PC spellcasters to provide limited magical protections and related effects.

Issue #29 is a very good one, filled with all the content I remember from my time reading the magazine. I continue to be pleased by the number of terrific Traveller articles published in White Dwarf, as well as the presence of longer, more detailed pieces about specific (and often unusual) topics. The first appearance of Oliver Dickinson's Pavis stories is simply the icing on the cake.

February 28, 2022

Coming Soon

February 27, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: Under the Pyramids

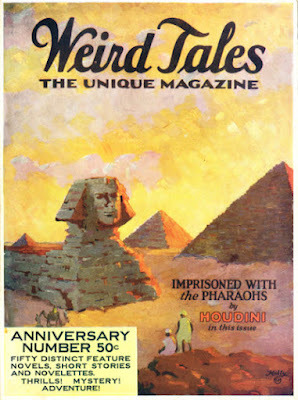

By the time he wrote most of the foundational stories of the Cthulhu Mythos for which he is remembered today, H.P. Lovecraft had already established himself as an important writer within the genre of weird fiction. So well regarded was he that, in early 1924, he was asked by J.C. Henneberger, the owner of Weird Tales magazine, to work as a ghostwriter for the world famous escape artist and illusionist Harry Houdini.

By the time he wrote most of the foundational stories of the Cthulhu Mythos for which he is remembered today, H.P. Lovecraft had already established himself as an important writer within the genre of weird fiction. So well regarded was he that, in early 1924, he was asked by J.C. Henneberger, the owner of Weird Tales magazine, to work as a ghostwriter for the world famous escape artist and illusionist Harry Houdini.Houdini was a regular contributor in the first year of The Unique Magazine's existence, providing a column ("Ask Houdini"), along several works of short fiction (the latter ghostwritten, perhaps by Walter B. Gibson, creator of The Shadow). Despite this, Weird Tales was in bad financial shape and needed a blockbuster issue to get itself out of debt. Henneberger's plan was to release a special "anniversary issue" in May 1924 that sold for twice the usual cover price but contained "fifty distinct feature novels, short stories, and novelettes," including a lengthy one by Houdini.

So important was this story that Henneberger not only turned to Lovecraft to ghostwrite it – he was very regarded by the magazine's readership at the time – but he also paid him $100 in advance. This was a significant amount of money at the time and Lovecraft was perpetually in need of remuneration, all the more so now that he was about to be married and move to New York City. He called the story was commissioned to ghostwrite "Under the Pyramids," but it was retitled "Imprisoned with the Pharaohs" upon its publication. The tale purports to be a first person account by Houdini of his experiences in Egypt in 1910, though the entirety of its content is fictitious and based on ideas proposed by Houdini and extensively expanded by Lovecraft.

"Under the Pyramids" is surprisingly compelling, drawing as it does on the mystique of ancient Egypt. If the story has a flaw that might explain its relative obscurity among readers today, it's that its first part is replete with historical, cultural, and geographical information, so much so that it sometimes reads more like an encyclopedia or travelogue rather than a work of fiction. Here's a relevant example of what I mean:

The Pyramids stand on a high rock plateau, this group forming next to the northernmost of the series of regal and aristocratic cemeteries built in the neighbourhood of the extinct capital Memphis, which lay on the same side of the Nile, somewhat south of Gizeh, and which flourished between 3400 and 2000 B.C. The greatest pyramid, which lies nearest the modern road, was built by King Cheops or Khufu about 2800 B.C., and stands more than 450 feet in perpendicular height.

And so on.

In his defense, I suspect that Lovecraft's readers would have been fascinated by these details. One must remember that Howard Carter had discovered Tutankhamun's tomb only two years before the publication of "Under the Pyramids," creating a global sensation that reverberated throughout the 1920s. Furthermore, this enumeration of mundane details grounds the story in mundane reality, perhaps leading the unsuspecting reader to believe that the tale's second part will be similarly prosaic.

Part two is where "Under the Pyramids" truly takes flight. Houdini is set upon by his local Egyptian guides, who bind him, hand and foot, and toss him into a "Stygian space" beneath the Temple of the Sphinx. One of these guides

mocked and jeered delightedly in his hollow voice, and assured me that I was soon to have my "magic powers" put to a supreme test which would quickly remove any egotism I might have gained triumphing over all the tests offered by America and Europe. Egypt, he reminded me, is very old and full of inner mysteries and antique powers not even conceivable to the experts of today, whose devices had so uniformly failed to trap me.

Lovecraft is unrelenting in maintaining that the narrator is Harry Houdini and, as in the excerpt above, there are frequent references to his athleticism and skill at escapology. However, Houdini's abilities are of little avail in the face the increasingly fantastical things he witnesses in the darkness.

I saw the horror and unwholesome antiquity of Egypt, and the grisly alliance it has always had with the tombs and temples of the dead. I saw phantom processions of priests with the heads of bulls, falcons, cats, and ibises; phantom processions marching interminably through subterraneous labyrinths and avenues of titanic propylaea beside which a man is as a fly, and offering unnamable sacrifice to indescribable gods. Stone colossi marched in endless night and drove herds of grinning androsphinxes down to the shores of illimitable stagnant rivers of pitch. And behind it all I saw the ineffable malignity of primordial necromancy, black and amorphous, and fumbling greedily after me in the darkness to choke out the spirit that had dared to mock it by emulation.

Lovecraft gives his imagination free rein in the second part of the tale, presenting a panoply of bizarre and suggestive imagery. The reader, like Houdini himself, is never sure whether what he is seeing is real or if it is in fact a waking dream brought on by the physical rigors of his current predicament. This possibility is buttressed by the fact that Houdini, after the fashion of a true Lovecraftian protagonist, faints not once but three times over the course of the story. I've seen some commentators, like S.T. Joshi, suggest that this was intended as a joke of some kind and I suppose it's possible, but, speaking for myself, I found it distracted from an otherwise captivating narrative.

Throughout "Under the Pyramids," Houdini is troubled by what he calls an "idle question," namely "what huge and loathsome abnormality was the Sphinx originally carven to represent?" I doubt anyone will be startled to learn that, before its conclusion, the tale presents an answer to this question and a satisfyingly lurid one at that. For me, though, it is the phantasmagoria of frightful sensations Houdini experiences that held my attention, such as this one:

From some still lower chasm in earth's bowels were proceeding certain sounds, measured and definite, and like nothing I had ever heard before. That they were very ancient and distinctly ceremonial I felt almost intuitively; and much reading in Egyptology led me to associate them with the flute, the sambuke, the sistrum, and the tympanum. In their rhythmic piping, droning, rattling and beating I felt an element of terror beyond all the known terrors of earth—a terror peculiarly dissociated from personal fear, and taking the form of a sort of objective pity for our planet, that it should hold within its depths such horrors as must lie beyond these aegipanic cacophonies. The sounds increased in volume, and I felt that they were approaching. Then—and may all the gods of all pantheons unite to keep the like from my ears again—I began to hear, faintly and afar off, the morbid and millennial tramping of the marching things.

If you're a fan of Lovecraft and his idiosyncratic style, "Under the Pyramids" is delightful. The story lacks some of the weightiness – and self-seriousness – of his Cthulhu Mythos efforts, but it nevertheless presents a clever weird tale that holds the reader's attention and contains a genuine surprise or two. Owing to the fact that I first encountered it early in my introduction to HPL, it's always been a favorite of mine; I hope others might find it as enjoyable.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers