James Maliszewski's Blog, page 111

April 7, 2022

Thoughts on What We're Playing

Several weeks ago, I made a short post, in which I asked readers what roleplaying games they were currently playing, how often they met to play, and how long they've been playing their current campaigns. The response to the post was remarkable, garnering more than 150 comments, which I believe is the most of any post on this blog. Likewise, the information provided in the comments was genuinely insightful, since it afforded me a small window into not just the readers of my own blog but perhaps into the wider hobby and, especially, the amorphous OSR scene.

I say "perhaps," because I'm not certain how representative the comments were of anything, including the readership of this blog. While 150+ comments is unquestionably a significant amount, that number is less than 5% of Grognardia's daily visitors and Grognardia itself is a but a small drop in the ocean of RPG-related content online. Consequently, I'm reluctant to draw any broad conclusions from the comments, since, much like election polling, there's a certain degree of self-selection going on with regards to who is willing to take the time to comment. Nevertheless, I did learn a few worthwhile things from the comments, which I'd like to share with you today.

The first is that there's a lot of gaming going on. That's very encouraging to me, because I often get the impression that roleplaying is, for many people, more of an aspirational hobby than one in which they participate regularly. Whenever I hear the triumphalist claim there are now more people gaming than there have been at any time in history, I tend to be skeptical. I have no doubt whatsoever that more people are buying RPG products than at any point in history, but actually playing with them? I'm not so sure. Still, the comments to my post make it clear that many readers do still roll the dice regularly with their friends and, as I said, I find that heartening.

The second thing I learned is that, even though the commenters are playing a wide variety of games today, the vast majority of them are playing some version of Dungeons & Dragons, which should surprise no one. What did surprise me was how many of those playing D&D are playing the current edition and by a significant number. I have theories as to why this might be the case – chief among them being the ease with which to recruit players – but the raw fact is that, even in the old school sphere, many gamers have adopted the new hotness.

Even so, good old Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, particularly in its Gygaxian First Edition, remains the go-to game for many commenters. Indeed, its popularity is only slightly less than that of the current edition and way ahead of that of any other game mentioned in the comments. Quite a few of you are also playing OD&D or one of its clones, with Old School Essentials, itself the new hotness within that realm, being more popular than Labyrinth Lord or even Swords & Wuzardry. Paizo's Pathfinder is another significant presence among commenters.

Outside of the world of D&D, there were several standouts, starting with RuneQuest. This surprised me a bit, though, in retrospect, it shouldn't have. In recent years, Chaosium has done an excellent job of rebuilding their most popular game lines, which is why Call of Cthulhu also figured prominently among non-D&D RPGs in the comments. Traveller was similarly well placed, thanks, I'd imagine, to the steady stream of product being published by Mongoose. I'm not a fan of the Mongoose version of Traveller, but I don't think there's any question that it's ensured the GDW classic still has a presence on game store shelves.

The third thing I learned is, while not the majority, there are still a fair number of commenters who are playing in campaigns that have been going on for more than two years. As an advocate of long campaigns, it's good to see this. That said, I also learned that many commenters are not involved in long campaigns and indeed many seem to play in lots of short-lived campaigns (and for a wide variety of reasons). I pass no judgment on these campaigns, having been in similar places in the past. I only note that the tendency toward campaigns that last two years or less than I first observed in the early 2000s, during the height of the 3e era, seems to have become a permanent feature of the hobby.

The final thing I learned is that online play, whether it be via video chat, virtual tabletop, or even forum-based play-by-post, is very popular. To some extent, this might simply be reflective of the disruptions of the last two years, which prevented more face-to-face gaming. On the other hand, I'd noticed a trend in this direction for years beforehand, in part, I think, because online gaming is so much easier to schedule and maintain. I know that's been true in my own life, so I can hardly blame anyone else of availing themselves of this particular technological boon.

Taken together, the comments suggest that roleplaying game campaigns are alive and well in 2022. At least some of my readers are indeed playing and playing regularly with their friends. That's absolutely delightful to hear, as I am ever more convinced that this hobby is a unique form of entertainment that is not merely fun in itself but that offers many benefits to its participants, not least of which being close contact with other human beings and exercise of the imagination. These are vital in my opinion and the world could use more of them both.

April 6, 2022

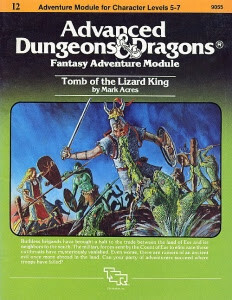

Retrospective: Tomb of the Lizard King

Depending on one's perspective, 1982 is either the penultimate year of D&D's Golden Age or close to the start of a transitional Electrum Age. These days, I incline more toward the latter interpretation and modules like 1982's Tomb of the Lizard King are part of the reason why. The module is written by Mark Acres, who's best known for his work on some of TSR's "lesser" RPG efforts (including my beloved

Gangbusters

). I was honestly surprised that Acres was its designer, as I hadn't recalled his ever writing anything for any edition of Dungeons & Dragons. I also think I had confused this module with

Against the Cult of the Reptile God

by Doug Niles, perhaps due to the presence of lizard men in both.

Depending on one's perspective, 1982 is either the penultimate year of D&D's Golden Age or close to the start of a transitional Electrum Age. These days, I incline more toward the latter interpretation and modules like 1982's Tomb of the Lizard King are part of the reason why. The module is written by Mark Acres, who's best known for his work on some of TSR's "lesser" RPG efforts (including my beloved

Gangbusters

). I was honestly surprised that Acres was its designer, as I hadn't recalled his ever writing anything for any edition of Dungeons & Dragons. I also think I had confused this module with

Against the Cult of the Reptile God

by Doug Niles, perhaps due to the presence of lizard men in both.Before even looking at the contents of the module itself, the first thing that's obvious is that it makes use of the then-new trade dress for AD&D modules – the first module to do so, I believe, even though I more strongly associate it with Pharaoh, published the same year. Aside from the gold bar across the top – visually similar to the gold spines on books like Monster Manual II – another notable feature is the AD&D logo with its distinctive draconic ampersand. Finally, Tomb of the Lizard King is billed as a "fantasy adventure module" rather than a "dungeon module" as were all its predecessors. Taken together, these changes demonstrate, I think, that AD&D was in the midst of a shift, esthetically if nothing else, away from its earlier form.

The adventure is written for levels 5–7 and includes eight pre-generated characters, as so many modules of the era did. I enjoy examining pre-generated characters, with an eye toward the power level of player characters presumed by the designer. The pre-gens here are pretty much in line with those of the time, with middling ability scores and hit points and comparatively few magic items. I prefer characters of this sort, but it's clear that, as time went on, this approach fell out of favor and presumed PC power increased considerably – a shift we'll see strongly during the Silver Age proper.

The adventure takes place on the plain of the River Ardo in the County of Eor, which has recently been beset by bandits. If none of those place names sound familiar, you're not alone. Tomb of the Lizard King is a "generic" module in that it's not specifically keyed to the World of Greyhawk setting, as most AD&D modules were at the time, if only tangentially. This is another shift worth noting, as it's one that becomes much more widespread as the 1980s wear on. In any case, the characters are asked by the Count of Eor (with the rather mundane name of John Brunis) to find out first what happened to the men he sent to deal with these bandits and who never returned and, if they can, to deal with the bandits themselves.

Of course, the bandits are no ordinary highwaymen but rather a coalition of evil men and monsters assembled by Sakatha, the titular lizard king. Sakatha, we learn, died more than two centuries ago, slain, like all his kind, by the ancestors of the people of Eor. Dying on the battlefield, he begged whatever powers that might hear him to have his revenge. Sakatha then rose from the dead as a vampire and has slowly been building up his power base so that he could avenge himself and his people upon Eor. (I feel like I should add that, in addition to being a vampire, Sakatha is also a 9th-level magic-user, so he's quite powerful.)

It's a good set-up for an adventure in my opinion and, for the most part, it doesn't disappoint. The encounters throughout, both in the obligatory wilderness section and in several underwound locales, are very challenging. In fact, I'm not really sure that they're suitable for 5th–7th level characters, not without a great deal of luck and planning on the part of the players. In that respect, I think Tomb of the Lizard King is in keeping with earlier AD&D adventures, which demanded attentive play and skill to survive. However much its presentation may differ from those of earlier modules, its level of difficulty still feels as if it were a product of previous years.

That said, the module does suffer from a lack of flavor. Yes, Sakatha is a compelling and well fleshed out antagonist and that's important. However, the Count of Eor, the realm he rules, and even the wilderness the characters explore while in his employ all feel bland and generic. There's none of the details or idiosyncratic flourishes one would find in Gygax's adventures, let alone the overwrought melodrama of Hickman's efforts. Instead, this is a fairly bare bones affair that's notable mostly for its clever villain and demanding encounters. Perhaps that is enough.

April 5, 2022

Wascally Wabbit

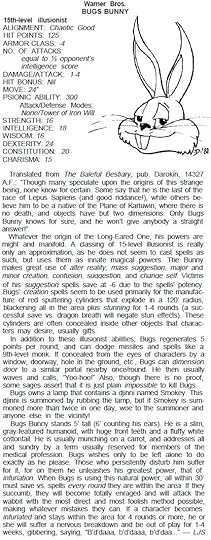

Also from Dragon #48 (April 1981) is the write-up below, written by Lawrence J. Schick and illustrated by Jeff Dee. Of particular interest is that Schick references elements of the original "Known World" setting that he co-created with the late Tom Moldvay in the mid-1970s (and that would later be incorporated into the D&D Expert Rulebook published in the same year as this article).

School Rule

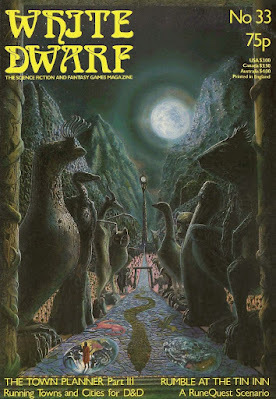

White Dwarf: Issue #33

Issue #33 of White Dwarf (September 1982) features a strangely compelling cover by Andrew George. I'm honestly not sure what it's supposed to be depicting, but, whatever it is, I find it interesting. The issue contains quite a pair of Traveller articles, starting with "Weapons for Traveller," which is a collection is new weapons for the game submitted by readers. Relatedly, there is "Guns for Sale" by Steve Cook. Though brief, this is a useful article that looks at the availability of various Traveller weapons through normal channels, taking into account factors such as tech level and law level. My main complaint about the article is that, like others in White Dwarf, it makes use of percentile dice, which are wholly unknown in Traveller.

Issue #33 of White Dwarf (September 1982) features a strangely compelling cover by Andrew George. I'm honestly not sure what it's supposed to be depicting, but, whatever it is, I find it interesting. The issue contains quite a pair of Traveller articles, starting with "Weapons for Traveller," which is a collection is new weapons for the game submitted by readers. Relatedly, there is "Guns for Sale" by Steve Cook. Though brief, this is a useful article that looks at the availability of various Traveller weapons through normal channels, taking into account factors such as tech level and law level. My main complaint about the article is that, like others in White Dwarf, it makes use of percentile dice, which are wholly unknown in Traveller. Continuing with the Traveller theme, "Open Box" reviews Striker , giving 6 out of 10, which I think is quite fair when one considers its complexity and general utility. Also reviewed are all four modules in the "S;ave Lords" series, which are collectively given 7 out of 10. Chaosium's Elric boardgame receives the same score, as does Flying Buffalo's Grimtooth's Traps. Perhaps I am seeing something that's not really there, but I've noticed that the reviews in "Open Box" are becoming somewhat more critical than they had been at the start of the column. I think that's a good thing overall, since the whole purpose of reviews in my opinion is to discuss, as objectively as one can, the good and the bad of a product so that a reader has a solid basis on which to decide whether to buy the product for himself. I'll be keeping a closer eye on "Open Box" in future issues to see if indeed my sense of things is borne out.

Part III of Paul Vernon's "The Town Planner" series focuses on "Running Towns and Cities," with special attention being paid to government, local customs, laws, calendars, events, and urban encounters. Taken together, these topics are among the most interesting and immediately useful ones that Vernon has tackled in this series. Consequently, I really enjoyed reading his thoughts and ideas. "Rumble at the Tin Inn" by Michael Cule is a mini-scenario for use with RuneQuest that's explicitly inspired by Lewis Pulsipher's "A Bar-Room Brawl" from issue #11. Like its predecessor, it includes a map with cut-out counters and game statistics for all the potential combatants.

Speaking of follow-ups (and Lewis Pulsipher), we get Part II of his "Arms at the Ready" series, the first part of which appeared in issue #31. Readers are treated to eight more weapons cards for use with AD&D. Oliver Dickinson's "Rune Rites" column looks at "Invisibility and Magic." In addition to presenting a magic item, "The Cap of Sight," the article includes a small piece written by Greg Stafford himself, entitled "Spells Which I Don't Use in My Campaign." Stafford explains that he finds spells like invisibility, concealment, and vision "make it hard for [him] to referee a decent game which includes drama and tension." For that reason, he does not make these spells "general available to regular people or adventurers." Fascinating!

"Brevet Rank for Low Level Characters" by Lewis Pulsipher is an odd article. The whole thing is premised on the idea that convention referees often encounter people who wish to join their adventure but who lack characters of sufficient level to do so. Pulsipher then puts forward a system by which the referee can "pro-rate" a low-level character so that he can participate in a high-level adventure. I have no particular objection to the guidelines Pulsipher offers, but why bother? Had not referees in the UK at the time heard of pre-generated convention characters? Chalk this one up to another installment in The Past is a Foreign Country.

"Fiend Factory" this month looks at psionic monsters with "All in the Mind." As is usually the case, the monsters are a mixed bag and include some truly bizarre creatures, like the Psi-Mule and Giant Mole (which is inexplicably possessed of several mental powers). More interesting, from a historical perspective if nothing else, is Zytra, Lord of the Mind Flayers, created by future science fiction author, Charles Stross (who also created the githyanki and githzerai). Finally, "Treasure Chest" is a true miscellany of material for D&D, from a new potion to a new spell to a system for handling wear and tear on armor.

All in all, it's a fine issue, with a good mix of material, though not quite as strong as the previous one. Even so, this coming issues match up with the period of my youth when I was an avid reader of White Dwarf. For nostalgia alone, I expect I'll enjoy re-reading them and, if my memories are not mistaken, they will contain a fair bit of material well worth re-visiting.

April 4, 2022

The Wages of Naturalism

Ironically, my own feelings about the consequences of Gygaxian Naturalism are in flux and with each passing day becoming more negative. To be clear: I'm still very much a proponent of consistent worldbuilding, which is what I think Gygaxian Naturalism is at its root. However, I increasingly feel as if many designers have mistaken consistency, which is generally an unalloyed good, for realism, by which I mean (in this case) operating according to rational – or even scientific – principles. In general, I don't think fantasy is very well served by most expressions of realism, as they will ultimately undermine the fantasy.

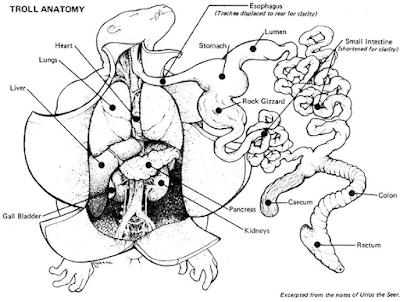

Maintaining consistency and coherence without toppling over into monomanical realism is not easy, so I try not to come down too harshly on lapses. Take, for example, this illustration (by Lisa A. Free) that appeared in the 1982 RuneQuest release, Trollpak, which is widely considered a masterclass in how to present a nonhuman species for use in a roleplaying game.

Taken in itself, this anatomical diagram of a troll is a wonderful piece of work that helps ground one of Glorantha's most fearsomely antagonistic species in an almost palpable reality – and that's part of my problem with it. As a setting, Glorantha has a (fairly) consistent tone, one grounded in myth. That's a huge part of its appeal to me. Illustrations like the one above, though, they detract from that mythic feel. Seeing one of the Uz laid out like, dissected and tagged like a cadaver from a Renaissance sketchbook, doesn't, in my opinion, add to the consistent worldbuilding of Glorantha, even if it does shed light on how trolls are able to eat anything. Instead, it actively detracts from any conception of trolls as weird or wondrous inhabitants of the Underworld.

Taken in itself, this anatomical diagram of a troll is a wonderful piece of work that helps ground one of Glorantha's most fearsomely antagonistic species in an almost palpable reality – and that's part of my problem with it. As a setting, Glorantha has a (fairly) consistent tone, one grounded in myth. That's a huge part of its appeal to me. Illustrations like the one above, though, they detract from that mythic feel. Seeing one of the Uz laid out like, dissected and tagged like a cadaver from a Renaissance sketchbook, doesn't, in my opinion, add to the consistent worldbuilding of Glorantha, even if it does shed light on how trolls are able to eat anything. Instead, it actively detracts from any conception of trolls as weird or wondrous inhabitants of the Underworld.Consider, too, this illustration from issue #72 (April 1983) of Dragon:

Almost anyone who was a reader of Dragon at the time should remember this piece of art, which accompanied "The Ecology of the Piercer" by Chris Elliott and Richard Edwards. At the time it first appeared, I absolutely adored this article and, judging from the fact that it inspired a regular feature in the magazine for many years to come, I suspect I was not alone in my feelings. Like the troll diagram, that of the piercer attempts to present a interpretation of a well-known monster that works pretty well on a rational, scientific level but that, in so doing, also undermines its weirdness and wonder.

Almost anyone who was a reader of Dragon at the time should remember this piece of art, which accompanied "The Ecology of the Piercer" by Chris Elliott and Richard Edwards. At the time it first appeared, I absolutely adored this article and, judging from the fact that it inspired a regular feature in the magazine for many years to come, I suspect I was not alone in my feelings. Like the troll diagram, that of the piercer attempts to present a interpretation of a well-known monster that works pretty well on a rational, scientific level but that, in so doing, also undermines its weirdness and wonder.Obviously, everyone draws the line of what constitutes "undermining" fantasy in a different place. But I nevertheless can't help but feel that the tendency toward describing fantastical beings by recourse to rationalistic, scientific categories is an error – an error not just in applying the principle of coherent worldbuilding that undergirds Gygaxian Naturalism but also in understanding fantasy itself. Once upon a time, science fiction was considered a species of the wider genre of a fantasy. SF took place in an imaginary world, as all fantasies do, but one whose imaginary elements were theoretically explicable by recourse to scientific axioms. The anatomical drawings above seem to be tentative examples of applying science fictional principles to fantasy.

I'm not yet convinced that the approach pioneered by Trollpak or "The Ecology of the Piercer" is the inevitable endpoint of Gygaxian Naturalism. At the same time, I could cite plenty of other examples down through the years that suggest that, for many people, consistency and coherence can only be understood in terms of rationalism and science, even when discussing a purely fantastical world and its inhabitants. I struggle with this myself, so I appreciate the difficulties, even as I regret the outcome.

Finieous Meets Jasmine

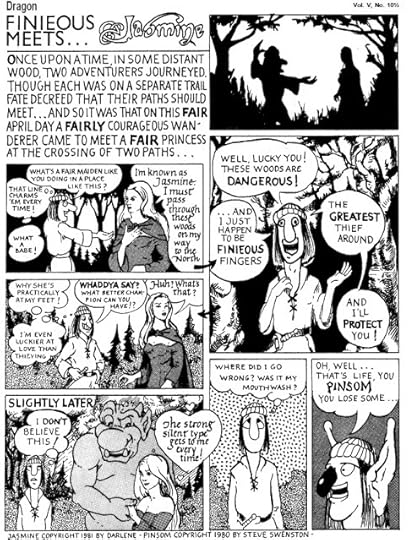

With the advent of a new month, I got the idea of looking back at Dragon magazine's April Fools' Day issues to see if I could find anything particularly noteworthy. Issue #48 (April 1981) included an insert entitled issue #48½ filled with numerous humorous articles. Also included was the following comic.

It's not clear to me whether the comic was actually written and drawn by J.D. Webster, creator of the actual Finieous Fingers comic, or if it, like the content of the strip itself, it's an affectionate spoof by someone else. Regardless, I found it amusing, not least for the way it subtly lampoons the self-seriousness of Darlene's Jasmine comic. Of course, the strip also references two other Dragon comics: Dave Trampier's incomparable Wormy and the oft-forgotten Pinsom by Steve Swenston (though, to be fair, it's easy to forget, given its very brief run).

It's not clear to me whether the comic was actually written and drawn by J.D. Webster, creator of the actual Finieous Fingers comic, or if it, like the content of the strip itself, it's an affectionate spoof by someone else. Regardless, I found it amusing, not least for the way it subtly lampoons the self-seriousness of Darlene's Jasmine comic. Of course, the strip also references two other Dragon comics: Dave Trampier's incomparable Wormy and the oft-forgotten Pinsom by Steve Swenston (though, to be fair, it's easy to forget, given its very brief run).I was (and am) a big fan of April Fools' Day content. They're a good way to puncture the pomposity of roleplayers and, as someone regularly prone to that particular flaw, a well done comedic jab is an act of public service. Likewise, humor of this sort is, in my opinion, powerful evidence of an emerging RPG sub-culture, one with its own unique references, allusions, and, of course, jokes. The fact that Dragon could annually devote several of its pages – not to mention the occasional page in other non-April issues – shows just how much the hobby had grown and evolved since 1974. Plus, it's just fun.

April 3, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Doom That Came to Sarnath

The early part of H.P. Lovectaft's literary career is marked by the influence of the Anglo-Irish author, Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron Dunsany, better known to posterity simply as Lord Dunsany. Between 1905 and 1919, Dunsany wrote numerous short stories that are set in a fictional world, Pegāna, with its own imaginary history and geography. These stories laid much of the groundwork for the evolution of the nascent genre of fantasy into what we know today (without which the hobby of roleplaying would likely not have been possible).

The early part of H.P. Lovectaft's literary career is marked by the influence of the Anglo-Irish author, Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron Dunsany, better known to posterity simply as Lord Dunsany. Between 1905 and 1919, Dunsany wrote numerous short stories that are set in a fictional world, Pegāna, with its own imaginary history and geography. These stories laid much of the groundwork for the evolution of the nascent genre of fantasy into what we know today (without which the hobby of roleplaying would likely not have been possible). Nowadays, Lovecraft's Dunsanian period tends to be overlooked, particularly by those enamored of his later, more famous tales of the "Cthulhu Mythos" (itself a term never employed by HPL himself). To the extent that these earlier stories are remembered, they're often mistakenly taken to be part of his "Dream Cycle." To some extent, Lovecraft himself is to blame for this misapprehension, because of the allusions and references he makes to his Dunsanian tales in works like The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath. Likewise, Lovecraft's admirers have, as ardent fans so often do, attempted to impose upon his canon clear divisions whereby a work belongs in one category or another, despite the evidence that Lovecraft himself was far less rigid in his own thinking.

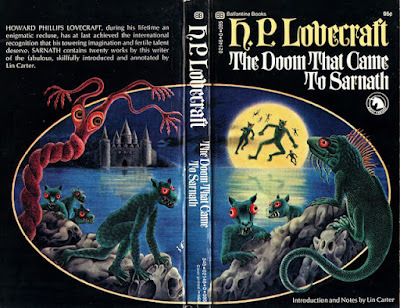

"The Doom That Came to Sarnath" is a good example of this phenomenon. Originally published in the June 1920 issue of the amateur fiction periodical, The Scot, the story was widely reprinted after Lovecraft's death, starting with the June 1938 issue of Weird Tales. Since I was unable to find an image of the issue of The Scot in which it premiered to accompany this post, I opted instead for the terrific cover of the 1971 Ballantine Adult Fantasy edition, painted by Gervasio Gallardo. My own introduction to the story came in the 1982 Del Rey collection of the same name with a cover by Michael Whelan, but I think I like the Gallardo version better.

The story begins in a way that makes clear Lovecraft's intentions:

There is in the land of Mnar a vast still lake that is fed by no stream and out of which no stream flows. Ten thousand years ago there stood by its shore the mighty city of Sarnath, but Sarnath stands there no more.

As I read it, "The Doom That Came to Sarnath" is a myth or legend coming down to us from the distant past, as Lovecraft implies immediately thereafter:

It is told that in the immemorial years when the world was young, before ever the men of Sarnath came to the land of Mnar, another city stood beside the lake; the grey stone city of Ib, which was old as the lake itself, and peopled with beings not pleasing to behold.

The story is filled with phrases like "when the world was young" that suggest to me at least that the reader isn't to understand the tale he tells as taking place in an imaginary or dream land but instead in the ancient and forgotten past of our own world, though, as we shall soon see, the matter is not cut and dried. Regardless, Lovecraft establishes that the beings of Ib were "in hue as green as the lake and the mists that rise above it" and "they had bulging eyes, pouting, flabby lips, and curious ears, and were without voice." One of the reasons I chose the cover above is because it features Gallardo's interpretation of what the beings of Ib looked like.

In time, men to the land of Mnar and founded the city of Sarnath. They marveled at the sight of the beings Ib.

But with their marvelling was mixed hate, for they thought it not meet that beings of such aspect should walk about the world of men at dusk. Nor did they like the strange sculptures upon the grey monoliths of Ib, for those sculptures were terrible with great antiquity. Why the beings and the sculptures lingered so late in the world, even until the coming of men, none can tell; unless it was because the land of Mnar is very still, and remote from most other lands both of waking and of dream.

The hatred of the men of Sarnath grew and, in time, resulted in a war in which all of the beings of Ib were slain and their "queer bodies [pushed] into the lake with long spears, because they did not wish to touch them." The men of Sarnath likewise toppled the monoliths of Ib and cast them into the lake. The only evidence of Ib the men kept was

the sea-green stone idol chiselled in the likeness of Bokrug, the water-lizard. This the young warriors took back with them to Sarnath as a symbol of conquest over the old gods and beings of Ib, and a sign of leadership in Mnar.

The men placed the idol in one of their own temples, but, on the following night,

a terrible thing must have happened, for weird lights were seen over the lake, and in the morning the people found the idol gone, and the high-priest Taran-Ish lying dead, as from some fear unspeakable. And before he died, Taran-Ish had scrawled upon the altar of chrysolite with coarse shaky strokes the sign of DOOM.

The story's titular doom does not come quickly and Lovecraft spends the remainder of the story describing the next thousand years of Sarnath's history, as it grows in power – and pride – within the land of Mnar, eventually becoming the capital of a mighty empire founded on hate and greed. Lovecraft presents these facts in a way that seemingly implies admiration of Sarnath and its glory, but it soon becomes clear that this is a mask for condemnation of its excesses and, by the end, Sarnath and its people pay the price for their past sins.

To call "The Doom That Came to Sarnath" a morality tale is probably simplistic. At the same time, Lovecraft is not at all subtle in his connecting the destruction of Ib with the later doom that befalls Sarnath. In any case, the story is luxuriously written, redolent with adjective-laden description that reminds a bit of Clark Ashton Smith, though utterly lacking in his black humor. Its almost Biblical rhythms and cadences practically demand that the story be read aloud. In the grand scheme of things, it's one of Lovecraft's minor works but it's nevertheless a successful one for which I have a strange affection.

April 1, 2022

The Secrets of sha-Arthan: Alignment

(The following is an excerpt from the current draft of the rules for my Secrets of sha-Arthan science fantasy setting. I typically only share excerpts like this with my patrons, but, in this case, I thought it might benefit from a wider audience. In addition, I think the ideas in this draft might be of value even to those without any interest in sha-Arthan.)

In sha-Arthan, alignment represents one’s loyalty to a person, organization, religion, realm, or philosophy. An alignment thus represents what a character values in life. Choosing an alignment is entirely optional; no character is required to have an alignment. However, there can be benefits that make aligning oneself attractive, just as there can be drawbacks that make it less so. Consequently, a character may have no alignment, preferring to be a free spirit or lone wolf, or he may change his alignment as he goes through life.

Choosing an AlignmentA newly generated character begins with no more than one alignment. He may eventually have up to three alignments at one time but no more. In general, a character can discard an alignment at any time, but may only gain a new one after attaining a new level, though, as with many things, the referee is the final arbiter of these matters.

Below are a three examples of alignments suitable for newly generated characters. Additional alignments, including those a character might adopt as he acquires more power and influence, are described on pXX. In addition, the referee is encouraged to create new alignments, using those present in this book as models.

Dran Jir DynastyThe Dran Jir Dynasty is one of about a dozen aristocratic families that have dwelt in da-Imer for centuries. Once possessed of great power, the coming of the Chomachto has diminished their influence, particularly since the King-Emperor abandoned the First City for his new capital at Tamas Tzora. Now, the Dran Jir look for ways to regain their status – such as the sending of their servants into the Vaults in search of artifacts of the Makers.

Requirements: Magically binding oneself to the Dran Jir as a kruva hijai (or “servant of the house”) in an ancient Ironian ritual.

Benefits: A character with this alignment gains the trust of the current head of the Dran Jir. He also gains limited access to dynastic resources and, more importantly, to an entrance to the Vaults unknown to the authorities of da-Imer.

Drawbacks: The binding ritual prevents the character from directly acting against the interests of the Dran Jir Dynasty or its members. Likewise, use of an unapproved entrance to the Vaults is a crime with potentially stiff penalties.

The Light of KulvuThe philosophy known as the Light of Kulvu (see pXX) is an ancient one, whose Unquestionable Precepts animated the empire that bore its name. Those precepts survived the wreck of the empire and are now held by many who find them a sure guide to understanding reality and living in harmony with it.

Requirements: Public acceptance of the precepts of the philosophy as outlined in The Mirror of Virtue.

Benefits: A character with this alignment gains a +2 reaction bonus with those who share it. If the result is Friendly, the character may gain access to food, accommodations, or information from his fellow Kulvuans. This, in turn, may lead to alignment with a specific school within the philosophy (e.g. Bejandrai, Ruketsa, etc.), some of which offer additional benefits.

Drawbacks: Except in those few lands that proscribe the Light of Kulvu (e.g. Alakun-Tenu), there are generally few drawbacks to adopting this alignment.

Viceroy TiakenSince King-Emperor Trelu vacated da-Imer, he placed its administration in the hands of a trusted viceroy. The current holder of that position, Tiaken Charsuna, is a very ambitious man in need of agents to further his own ends (which, some say, include the usurpation of the Solar Throne).

Requirements: Swearing a personal oath to the Viceroy of da-Imer in which the character agrees to undertake certain special tasks in the Vaults and the First City on his behalf whenever commanded to do so.

Benefits: A character with this alignment gains a reduced exit charge to any Vault Warrant (see pXX) to which he is a signatory. At levels 1–2, the charge is 15%; at levels 3–5, 10%; at levels 6+, it is waived entirely. In addition, the character may be able to obtain preferential treatment by viceregal guards and officials with da-Imer.

Drawbacks: Viceroy Tiaken is constantly scheming. A character aligned with him will often find himself entangled in all manner of stratagems – whether he wishes to become involved or not.

March 31, 2022

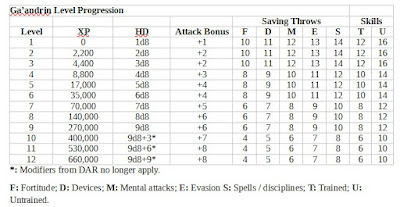

The Secrets of sha-Arthan: The Ga'andrin

Last Summer, I presented one of the nonhuman species of sha-Arthan, the Chenot. Today, I'd like to present another, the Ga'andrin. They're one of the most common nonhumans in the setting, governing several significant realms, as well as many minor ones.

A ga'andrin by Zhu BajieGa’andrin

A ga'andrin by Zhu BajieGa’andrin

Hit Dice: 1d8

Maximum Level: 12

Armor: Any, including shields

Weapons: Any

Languages: Tana’a, Janeksa

Ga’andrin (gah-ahn-DREEN) are a species of wiry, vaguely reptilian beings known for their aggression and fortitude. They stand about 5½’ tall and weigh 120 pounds. Ga’andrin are rivals and occasional allies of Man, ruling several realms of their own. They are redoubtable warriors whose legions are feared across sha-Arthan.

Alien MindOwing to their unusual thought processes, Ga’andrin are immune to the adept disciplines ESP, suggestion, and telepathy. The immunity is natural and cannot be suspended, even by a Ga’andrin who wishes to do so. The immunity also applies to psychogenic devices that mimic the effects of these disciplines.

CombatGa’andrin can use all types of weapons and armor.

Leap Attack

With sufficient room, Ga’andrin can leap up to 10’ forward, granting a +1 bonus to the first attack roll after the leap. If armed with an impaling weapon, the attack counts as a charge and deals double damage on a successful hit.

Shaina-senseGa’andrin believe that all living things generate an energy they call shaina p(shy-NAH), which they can sense. While most human sages scoff at such notions, it remains clear Ga’andrin can sense something, which enables them to detect living beings within 60’, even in total darkness. This shaina-sense makes Ga’andrin harder to surprise, reducing the chance to 1-in-6 under most circumstances.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers