James Maliszewski's Blog, page 108

June 9, 2022

The Tékumel Interview

Last week, Sean McCoy, designer of Mothership, asked me if I'd be willing to be interviewed about my experiences refereeing my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. Sean was particularly interested in what I'd done to keep the campaign running for the last seven years and I hope I provided some answers useful to others. Since I return to blogging almost two years ago, I've been beating the drum for long campaigns, but I recognize that this is outside many people's experiences, which is why I keep talking about it. Odds are it'll remain a significant theme on Grognardia for quite some time to come.

In any case, the interview has been posted here, if you're interested. (Apologies in advance: the interview long and the font size on Sean's blog is quite small.)

Gold as Experience

As characters meet monsters in mortal combat and defeat them, and when they obtain various forms of treasure (money, gems, jewelry, magical items, etc.), they gain "experience". This adds to their experience point total, gradually moving them upwards through the levels.–Dungeons & Dragons, Volume 1, p. 18 (1974)

The importance of finding treasure to a character's level advancement is a foundational feature of the Gygaxian presentation of D&D. In fact, after the publication of Greyhawk in 1975, which introduced a new – and less rewarding – method for calculating the XP of defeating monsters, finding treasure only rose became more importance. In AD&D, which uses a roughly similar system, Gygax explains that the system is intended to be an abstraction rather than reflective the in-game activities by which a character might "actually" advance in the skills and abilities of his chosen class.

I have never had any significant problems with this set-up. I accepted it without question when I was first introduced to D&D more than forty years ago and have made good use of it in multiple campaigns in the years since (including in my D&D-derived Empire of the Petal Throne campaign). I largely agree with Gygax that it's a perfectly workable compromise for a game whose rules don't (generally) possess a high degree of detail (see the one-minute combat round as another example of this in action).

However – you knew there'd be a "however" – I've been thinking lately about the need for experience and advancement systems for roleplaying games. In doing so, I began to think about the idea of using gold and other monetary treasure in a slightly different way. In Chaosium's RuneQuest, characters can improve both characteristics and skills through training. This training takes two things: time and money. A character who lacks either cannot make use of this method of improvement and must instead rely on the much more unpredictable method of experience rolls after the successful use of a skill in an adventure. It's worth noting, too, that even spells are acquired by "buying" them, usually from a cult.

Beginning characters often lack sufficient funds to buy all the training and spells they desire. That's why the cults and guilds of RuneQuest sometimes extend credit to neophytes, enabling them to take on a debt in exchange for training. This not only makes beginning characters a little more prepared for the adventuring life than they would otherwise be, but it establishes a connection between the character and the cult. In this way, beginning characters are immediately connected to the setting, one the referee can then use in the course of the campaign. It's an inspired idea to my mind and one I think more games should look to for inspiration.

This brings me back to the use of gold as a measure of experience in Dungeons & Dragons. As I've been thinking about this matter, I find myself wanting something akin to RuneQuest. Instead of a character simply improving all of his class-based abilities as soon as his experience total reaches a certain threshold, wouldn't it be more interesting – I won't say "realistic" – if instead he could use his gold to buy training that improved his abilities piecemeal. For example, he could employ a weapons master to increase his combat skills or acquire access to new spells at the sorcerer's guild and so on. Even mechanics like hit points and saving throws could be acquired through training of some sort or another.

Now, I realize that AD&D at least already possesses training rules and that, to some extent, they exist to explain the purpose of the large sums of money needed to gain new levels. However, like so much in D&D and its descendants, they're very abstract, more abstract, I would argue, than many similar systems in the game. Mind you, I speak from some degree of ignorance, since I cannot recall ever having made use of these rules, nor did I ever know anyone who had, until relatively recently. It's quite possible that AD&D's rules work very well and achieve the kind of in-setting connection I increasingly see as vital to a campaign's long term success.

One thing the AD&D training rules do seem to do is take time. Much like those in RuneQuest, a character will spend weeks of in-game time training the new abilities he's acquired upon gaining a level. That's something I very much appreciate. Between my House of Worms campaign and the Pendragon campaign in which I'm currently playing, I am more convinced than ever that a long campaign should encompass years or in-game time, with characters and events growing and changing in the process. This is an area where RPGs excel and it ought to be embraced.

June 8, 2022

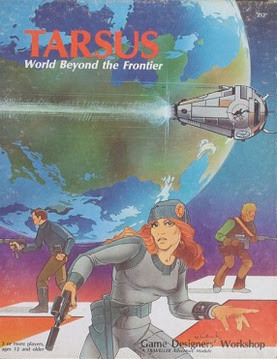

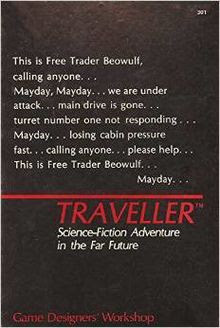

Retrospective: Tarsus

A common knock against the official Third Imperium setting for GDW's Traveller is that it's simply too big. Encompassing 11,000 worlds spread over nearly 300 subsectors, there's simply no way a referee can make use of it all except in a cursory way. Even a single sector, like the Spinward Marches or Solomani Rim, still contains close to 500 planets. The end result is that, for all its breadth and diversity, the Third Imperium will be little than an abstraction in most campaigns that make use of it.

A common knock against the official Third Imperium setting for GDW's Traveller is that it's simply too big. Encompassing 11,000 worlds spread over nearly 300 subsectors, there's simply no way a referee can make use of it all except in a cursory way. Even a single sector, like the Spinward Marches or Solomani Rim, still contains close to 500 planets. The end result is that, for all its breadth and diversity, the Third Imperium will be little than an abstraction in most campaigns that make use of it.

There's more than a little truth to this criticism, though, at the same time, I also feel that using the Third Imperium as a loose backdrop is exactly what the referee should be doing. Focusing too much on large scale sector-wide events, like the Fifth Frontier War, is precisely where GDW went wrong in its later development of Traveller. In my opinion, the company – and the game – would have been much better served by focusing instead on smaller scale details, such as individual subsectors or even worlds.

While the much celebrated The Traveller Adventure did the former, 1983's Tarsus: World Beyond the Frontier did the latter and did it very well indeed. Located in the unaligned District 268 subsector of the Spinward Marches, Tarsus is a non-industrial, agricultural world that's home to some 2.2 million human beings. Consequently, it's something of a backwater planet, though it maintains economic ties to both the Imperium, which it hopes to join one day, and other nearby interstellar powers, like the Sword Worlds.

Tarsus was released as a boxed set and included a 24-page World Data book (written by Marc Miller and Loren Wiseman) that detailed the planet, its history, local government, ecology, and more; a color map of the planet; a color map of an important region of the planet (Tangle Wald); a map of District 268 subsector; five 4-page adventure pamphlets; and a dozen pre-generated character cards. It's an excellent collection of material, attractively presented. Taken together, the referee has more than enough information to provide many months' worth of adventure on Tarsus itself, even longer if the characters eventually expand their scope beyond the planet itself to its neighbors in the subsector.

With its focus on agriculture and ranching nobbles (a large, horned, grazing animal), Tarsus has a vaguely Western feel to it. The whole planet reminded me of an unincorporated territory of the 19th century United States, on the verge of consideration for statehood, with various interests lobbying one way or the other. Indeed, there's much discussion of the voting system employed on Tarsus, which not only allows the open buying and selling of votes but also the buying and selling of them by newcomers to Tarsus. By law, only individuals can hold votes, though they may hold multiple votes, and may freely vote on behalf of others, like offworld corporations, that cannot themselves legally vote. It's a situation ripe for political machinations and corruption – not to mention adventure.

Of course, there's more to Tarsus than political maneuvering. The planet is a giant sandbox, with plenty of scope for a variety of approaches to its content. Player characters could, for example, become involved in nobble ranching, working for or against a megacorporation, exploring the Tangle Wald, cataloging the planet's native life, and more. There are also several flashpoints for armed conflict, as well as mercenary company in need of new recruits. This is in addition to the presence of many local patrons, a staple of Traveller adventures and a good way to kick off a campaign or extended adventure on this frontier world.

If one were to complain about Tarsus, it's that the information it presents about the planet and its conflicts is diffuse. The referee needs to read through all the included material several times to get a good handle on it, but, to my mind, that's the job of any good referee. Having done so, the referee should have little trouble keeping things the players and their characters engaged for a long time. With so many worlds in the Third Imperium, Tarsus is thus a good example of the kind of thing I wish GDW had done more often: fleshing out a single world in sufficient detail to demonstrate how much fun could be had be spending an extended period of time there. The game is called Traveller for a reason, to be sure; that doesn't mean the characters should always be on the move, Tarsus is a world worth visiting.

June 7, 2022

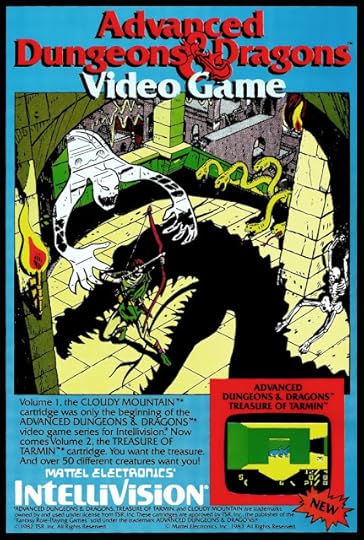

You Want the Treasure

Looking at it now, what's notable is the dissonance between the dynamic, well-executed artwork of the advertisement and the flatness of the screen shot in the bottom righthand corner. Such a comparison is probably not fair, given the technical limitations of video game consoles in 1983, but that doesn't make it any less true. Of course, this didn't stop my best friend and I from playing the game whenever we could (though I'm now not sure whether he owned the first or the second game – or both – since there's not much to distinguish them from one another).

Looking at it now, what's notable is the dissonance between the dynamic, well-executed artwork of the advertisement and the flatness of the screen shot in the bottom righthand corner. Such a comparison is probably not fair, given the technical limitations of video game consoles in 1983, but that doesn't make it any less true. Of course, this didn't stop my best friend and I from playing the game whenever we could (though I'm now not sure whether he owned the first or the second game – or both – since there's not much to distinguish them from one another).

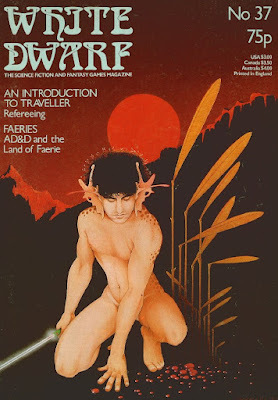

White Dwarf: Issue #37

Issue #37 of White Dwarf (January 1983) features a cover by Emmanuel that I assume is inspired by an article within entitled "Faeries," about which I'll speak presently. Like all of Emmanuel's previous covers (including that of the

Fiend Folio

), it's quite striking and very different than the kind of artwork I instinctively associate with RPG magazines. That may say more about my own narrow perspectives, I don't know. Regardless, it's a strangely compelling piece and is a good reminder that "fantasy" artwork isn't limited to the technically proficient but soulless style seen too often on this side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Issue #37 of White Dwarf (January 1983) features a cover by Emmanuel that I assume is inspired by an article within entitled "Faeries," about which I'll speak presently. Like all of Emmanuel's previous covers (including that of the

Fiend Folio

), it's quite striking and very different than the kind of artwork I instinctively associate with RPG magazines. That may say more about my own narrow perspectives, I don't know. Regardless, it's a strangely compelling piece and is a good reminder that "fantasy" artwork isn't limited to the technically proficient but soulless style seen too often on this side of the Atlantic Ocean.Ian Livingstone's editorial begins by focusing on the relative decline in the British pound compared to the US dollar and its adverse effect on the pricing of imported goods, like RPGs. This, in turn, leads him to wonder why, seven years after the arrival of Dungeons & Dragons, there is still no commercially viable British competitor. Games Workshop would, of course, rectify this matter in time, starting with (I believe) Golden Heroes in 1984, followed by Judge Dredd in 1985, and, of course, Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play in 1986.

"Faeries" by Alan E. Paul discusses, as its subtitle explains, "AD&D and the Land of Faerie." The article is basically an overview of British and Celtic folkloric notions about fairies, fairy creatures, and the otherworldly realm whence they come, with an eye toward incorporating these things into an AD&D game. It's a good effort and genuinely interesting, though I am generally well inclined toward attempts to introduce some authenticity into D&D's deracinated monster roster. However, "Faerie" is very light on specifics and contains no rules or rules modifications to aid the referee in this goal. Consequently, I found myself wanting more.

Andy Slack continues his "Introduction to Traveller," this time offering advice to referees. Like its predecessor, it's well done for what it is, though, as I perpetually say when approaching articles like this one, it's difficult to judge it properly decades after so many of its insights have passed into conventional wisdom. On the other hand, "Bloodsuckers" by Marcus L. Rowland is an unambiguously excellent article. As its title implies, it's about vampires, specifically for use with Dungeons & Dragons. What Rowland does is present referees with a "vampire construction kit" filled with lots of ideas and options. They're presented in the form of random tables, but the referee could just as easily choose those options he prefers. The end result is a much more varied – and unpredictable – kind of undead monster.

"Open Box" reviews three products this month, starting with Chaosium's SoloQuest for use with RuneQuest, which the reviewer judged excellent, giving it a 9 out of 10. Slightly less well received (7 out of 10) was TSR's Star Frontiers . Reviewer Andy Slack it less "realistic" and more "action adventure" oriented than Traveller, which is a fair, if common, knock against the game. Finally, there's Crasimoff's World, a play-by-mail fantasy RPG of which I've never heard. The reviewer likes it well enough (8 out of 10), though it's hard to understand fully what the game was like to play. Mind you, PBM gaming is a huge black hole in my own experience of the hobby, so I must admit to having a general difficulty in comprehending how they worked in practice.

"The City in the Swamp" by Graeme Davis is a remarkable AD&D scenario for characters of levels 5–7. The premise is that a gray slaad had been sent to spread some chaos on the Prime Material Plane and failed. Rather than return to Limbo in disgrace, he instead fled into a swamp to hide among the toad-like gralthi (a new monster race). A death slaad was sent to do the job the gray slaad failed to do and then, shapechanged into human form, he hires a group of player characters to go into the swamp and deal with his wayward kin. It's a very unusual set-up but a clever one that reminds me of a little of a lost story of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser or even Elric. My only real complaint is that it's difficult to read, as many White Dwarf articles were, thanks to both its small font size and its being printed on silhouetted pages.

"D&D Scenarios" by Lewis Pulsipher is a collection of brief adventure ideas for Dungeons & Dragons.

When I say "brief," I mean it. None of the ideas is fully fleshed out and most are only a paragraph or two long. Like the "Introduction to Traveller" piece earlier, it's hard to judge articles like this in retrospect. I can only say that I wasn't inspired, let alone blown away, by any of the ideas presented here. How much of that reflects my current vantage point is hard to say. Much more compelling was this month's installment of the "Fiend Factory," which presents four new monster species, the standout being the weed-delvers, a race of ancient cephalopods that ruled the seas eons ago. Also called the Wet Ones, the weed-delvers come in three varieties and are Chaotic Neutral in alignment, meaning the referee can use them in a multitude of ways, not simply as straight up antagonists."Magic Quest" offers up three new spells and one magic item for RuneQuest, while "Starbase" provides a prospecting vehicle for Traveller (complete with a schematic diagram). Finally, "Encumbrance without Tears" is an optional, simpler encumbrance system for use with AD&D. There's no question that this system is better than the standard version, but it's still too number-heavy for my present tastes. Mind you, I've never been a stickler about encumbrance, so I'm probably not the intended audience for articles like this.

This is a very good issue, buoyed in large part because of the excellent vampire article and the terrific AD&D scenario. Both heavily remind of the things I liked best about White Dwarf when I was a reader of the magazine in the early to mid-1980s. Both also encapsulate a certain intangible quality that I strongly associate with "British fantasy." They're both excellent palate cleansers for gamers like myself whose earliest experiences of fantasy are limited primarily to created by Americans (and American game companies). Good stuff!

June 6, 2022

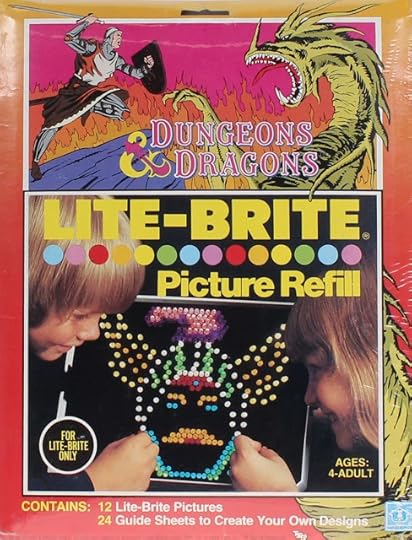

Create Exciting Color Pictures with Light!

I'm a well-known meanie when it comes to the brandification (and kiddie-fication) of Dungeons & Dragons by TSR in the mid-1980s. For that reason, I apologize in advance for my instinctive disdain of products like the Dungeons & Dragons Lite-Brite Picture Refill. Bear in mind that, in 1984, when this was released, I was almost 15 years old and at the height of my adolescent snobbery. That 15 year-old still slumbers within my middle-aged shell. When I look at images like this one, it's hard to keep him in check.

On first glance, I wondered why Bozo the Clown was pictured on the front of this thing. As I looked closer, I realized that the kids were in fact creating an image of Strongheart the Paladin, but I can't be the only one who had to squint to recognize him, can I?There were apparently a dozen Lite-Brite patterns included in this refill set, all of which are depicted below, though they're admittedly hard to discern. Most of them look to depict characters and monsters from the LJN D&D toyline, like the aforementioned Strongheart. More interesting, I think, is that Hasbro now owns Lite-Brite, alongside Dungeons & Dragons (and just about everything else I remember from my childhood).

On first glance, I wondered why Bozo the Clown was pictured on the front of this thing. As I looked closer, I realized that the kids were in fact creating an image of Strongheart the Paladin, but I can't be the only one who had to squint to recognize him, can I?There were apparently a dozen Lite-Brite patterns included in this refill set, all of which are depicted below, though they're admittedly hard to discern. Most of them look to depict characters and monsters from the LJN D&D toyline, like the aforementioned Strongheart. More interesting, I think, is that Hasbro now owns Lite-Brite, alongside Dungeons & Dragons (and just about everything else I remember from my childhood).

Are Character Advancement Rules Necessary?

I've never made any secret of the fact that GDW's Traveller is my favorite roleplaying game. Over the years, I've played it a lot – perhaps not as often as Dungeons & Dragons but that's to be expected, I think. Fantasy RPGs have always been more popular than science fiction ones and D&D was (and is) the proverbial 800-lb. gorilla of fantasy roleplaying games. Even so, Traveller has had a profound influence on the way I look at – and play – RPGs. Indeed, it might well have had a greater influence on me than even Dungeons & Dragons.

I've never made any secret of the fact that GDW's Traveller is my favorite roleplaying game. Over the years, I've played it a lot – perhaps not as often as Dungeons & Dragons but that's to be expected, I think. Fantasy RPGs have always been more popular than science fiction ones and D&D was (and is) the proverbial 800-lb. gorilla of fantasy roleplaying games. Even so, Traveller has had a profound influence on the way I look at – and play – RPGs. Indeed, it might well have had a greater influence on me than even Dungeons & Dragons.I mention this because twice in recent weeks I've been asked about how I handle character advancement in my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. Though obviously derived from OD&D, EPT includes a number of unique mechanical features, including reduced experience points as characters rise in level. The practical effect of these reductions is that, unless one's campaign is focused very heavily on underworld exploration and the acquisition of huge amounts of treasure, character progression stalls out at about level 6 or 7. That's what has happened in House of Worms.

In Traveller, once you've generated your character, his characteristics or skill levels will probably never improve (though characteristics can decrease, due to the effects of aging). As the game explains,

Characters already know their basic physical and mental parameters; their basic educational and physical development have already occurred, and further improvement can only take place through dedicated endeavor. Experience gained as the character travels and adventures is, in a very real sense, an increased ability to play the role which he or she has assumed.

This is a dramatic counterpoint to the approach of D&D or indeed almost any other roleplaying game, where regular mechanical improvement is, if not the entire point of the game, a major feature of it. Traveller, by contrast, largely eschews this; the "reward" of playing Traveller over time is "increased ability to play the role" the player has adopted. In other words, the player becomes more experienced rather than his character.

Note the distinction I made: regular mechanical improvement, by which I meant things like increased hit points, combat ability, saving throws, etc. Traveller provides little scope for that after character generation and yet, despite their absence, I can't recall a single complaint from anyone with whom I've played the game over the years. Certainly no one in my Riphaeus Sector campaign was aggrieved by this state of affairs. Of course, a lack of regular mechanical improvements is not the same thing as a lack of all improvements. Whenever I've played Traveller, the characters have improved, through the acquisition of better gear, greater knowledge, and more far-reaching influence. None of this is insignificant and, in fact, I would argue that most of these non-mechanical improvements ultimately have longer-lasting consequences (particularly in long campaigns).

This is certainly what I have observed in the House of Worms campaign. Though no player character has acquired any new hit points or spells in a very long time, I don't think anyone involved in the campaign would attempt to make the claim that his character hasn't improved with time. For example, the characters began, seven years ago, as minor scions of the mid-ranked House of Worms clan in the city of Sokátis. Through a combination of skill, cleverness, and dumb luck, they're now in positions of some power and influence within Tsolyánu. In addition, they've learned more about the world of Tékumel, knowledge that has served them well as they attempt to unravel the mysteries of Achgé Peninsula. As in my Traveller campaigns of old, not a single player has ever complained about his character's "lack of improvement."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, as I continue to work – albeit more slowly than I'd hoped – on The Secrets of sha-Arthan, the question of the mechanical improvement of characters is something I'm pondering. Are character advancement rules even necessary? Do we simply include them in nearly every RPG simply because D&D did so in 1974? I haven't made up my mind on this matter, but, between a lifetime of playing Traveller and the last seven years of my House of Worms campaign, I'm seriously beginning to wonder about their presumed necessity. At the very least, I'm looking more closely at experience and advancement than I have until now, with an eye toward understanding their purpose and effect on gameplay. What can we learn from Traveller and might its approach not be a better one than the never-ending mechanical escalation of Dungeons & Dragons?

Dungeon Dragon Battle

For those of you into 3D printing, you might find this reproduction of the iconic Erol Otus cover to the 1981 Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set interesting. I know next to nothing about 3D printing – or painting for that matter – but it's hard not to be impressed by this!

June 5, 2022

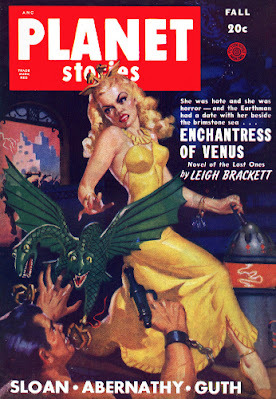

Pulp Fantasy Library: Enchantress of Venus

The distinctions separating the literary genres of fantasy and science fiction are fine ones, especially when dealing with early examples of the latter. For example, is

A Princess of Mars

a work of science fiction because its story takes place on the very real planet of Mars or is it a mere fantasy because so many of its setting details are incompatible with what we now know about the Red Planet? Over the decades, it's been a frequently contentious issue, hence the proliferation of even finer literary genres – planetary romance, science fantasy, and sword-and-planet, to name but a few – intended to put an end to such questions. As I've gotten older, I've simultaneously become less interested in these matters and more accepting of an expansive definition of "fantasy" that includes all types of imaginative fiction.

The distinctions separating the literary genres of fantasy and science fiction are fine ones, especially when dealing with early examples of the latter. For example, is

A Princess of Mars

a work of science fiction because its story takes place on the very real planet of Mars or is it a mere fantasy because so many of its setting details are incompatible with what we now know about the Red Planet? Over the decades, it's been a frequently contentious issue, hence the proliferation of even finer literary genres – planetary romance, science fantasy, and sword-and-planet, to name but a few – intended to put an end to such questions. As I've gotten older, I've simultaneously become less interested in these matters and more accepting of an expansive definition of "fantasy" that includes all types of imaginative fiction.In the case of Leigh Brackett's tales of Eric John Stark, many of which appeared in the pages of Planet Stories in the 1940s and '50s, this primal concern nevertheless resurfaces. Even in 1949, when Brackett wrote her first story of Stark, enough was known about the other worlds of our solar system that there was little plausibility to their being habitable by mankind without significant technological aid, let alone having intelligent natives of their own. Was Brackett then writing fantasy or did her stories still qualify as science fiction, albeit of an old fashioned sort – or is this, as I increasingly feel, a distinction without a difference?

Of course, little of this matters, as Stark's adventures are engaging yarns told with great enthusiasm. "The Enchantress of Venus," which first appeared in the Fall 1949 issue of Planet Stories, amply demonstrates what I mean. Second in the chronology of the tales of Stark, the novella takes place, as its title suggests, on the planet Venus, renowned for its "seas" of buoyant, phosphorescent gas. This detail is important because, as the story begins, Stark is aboard a ship making its way across one such Red Sea toward the town of Shuruun.

Shuruun is, to borrow a phrase, a wretched hive of scum and villainy. Stark is no stranger to such places and thus has no fear of the town. However, he only sought it out to find his friend, Helvi, "the tall son of a barbarian kinglet," who had gone into the town previously and never returned. Stark feels an obligation to locate Helvi and, if necessary, rescue him from whatever peril awaited him in Shuruun. Like so many pulp fantasy protagonists, Stark lives by his own code of honor, one that places great value in friends.

Malthor, the captain of the ship on which he is traveling, repeatedly suggests that Stark, whom he recognizes as a stranger, due to his black Mercurian skin, would do well to lodge with him when they reach Shuruun. Each time, Stark declines. As it turns out, he has good reason to do so: Malthor's true intentions are wholly sinister. Just as the ship gets within sight of the "squat and ugly town" that "crouch[ed] witch-like on the rocky shore, her ragged skirts dipped in blood," Malthor and some of his crew attack Stark in an attempt to take him prisoner, though for what precise purpose he did not know (and would not until later in the story). Rather than suffer this fate, Stark dives overboard into the Red Sea.

The surface of the Red Sea closed without a ripple over Stark. There was a burst of crimson sparks, a momentary trail of flame going down like a drowned comet, and then—nothing.

Stark dropped slowly downward through a strange world. There was no difficulty about breathing, as in a sea of water. The gases of the Red Sea support life quite well, and the creatures that dwell in it have almost normal lungs.

Stark did not pay much attention at first, except to keep his balance automatically. He was still dazed from the blow, and he was raging with anger and pain.

Properly scientific or not, this is evocative stuff and a reminder of why Brackett made such a splash (no pun intended) in the world of pulp fantasy during the 1940s and '50s.

Emerging from the sea, Stark makes his way to Shuruun in search of Helvi. He is almost immediately recognized as a stranger by the locals, who confront him and appear ready to attack. Before this can occur, a white-haired Earthman named Larrabee calls out and invites him to drink with him. Larrabee, we soon learn, is a notorious thief who "got half a million credits out of the strong room of the Royal Venus." In the nine years since, he has holed up in Shuruun to avoid being found by the authorities. When Stark introduces himself, Larrabee mentions that he knows his name from a wanted poster as "some idiot that had led a native revolt somewhere in the Jovian Colonies—a big cold-eyed brute they referred to colorfully as the wild man from Mercury."

Stark is amused by this description of himself but soon shifts the conversation to local matters, in particular the whereabouts of Helvi. Larrabee claims not to have seen him and instead speaks of the Lhari, "the Lords of Shuruun," who are "always glad to meet strangers." Hearing this, Stark decides he to call on the Lhari to see if they might know something about Helvi. Along the way, he meets Zareth, the teenage daughter of Malthor, who'd been sent into Shuruun to find him and then lure him into an ambush outside the city. Then, he'd be handed over to "the Lost Ones," who dwell in the interior of the swamp and have an interest in strangers like Stark. Zareth doesn't follow through on her father's plans, though, because he beats her and she hates him. However, she has no interest in joining Stark in visiting the Lhari, who frighten her as much as her father.

If you're having difficulty keeping all these narrative threads – Malthor, the Lhari, the Lost Ones – straight in your head, that's understandable. Brackett throws a lot at her readers at the beginning of "The Enchantress of Venus" and its can be confusing at times. Fortunately, she's a very skilled writer and repays the patience and forbearance shown to her. By the time Stark enters the castle of the Lhari and meets them, in all their decadent glory, for the first time, that things begin to make a great deal more sense. In some ways, that's the real beginning of the novella and the action barrels along from that point until it reaches its ultimate, satisfying conclusion. It's a lot of fun to read and reminds me, in some ways, like many of Robert E. Howard's tales of Conan the Cimmerian: a "wild" outsider finds himself caught up in the machinations of several sinister factions and must find a way to extricate himself from their clutches. What's not to love?

May 15, 2022

Wandering DMs

Dan Collins and Paul Siegel have once again asked me to appear on their Wandering DMs channel this afternoon at 1pm EDT. This time, I'll be talking about the ups and downs of refereeing a RPG campaign for the last seven years. Though obviously some of what I have to say will be specific to my ongoing House of Worms campaign, much of it – most of it, I hope – will have more general applicability to any long-running RPG campaign.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers