James Maliszewski's Blog, page 105

July 26, 2022

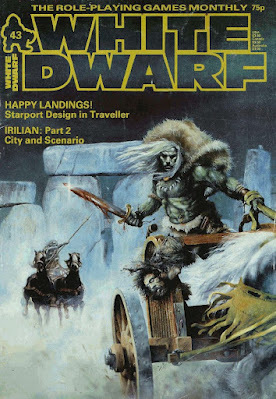

White Dwarf: Issue #43

With issue #43 of White Dwarf (July 1983), we are well within the range of issues I remember strongly from my youth. This is the period before I'd actually subscribed to the magazine – that would come a little while later – but after I'd made it a point to pick up a new issue each month. Consequently, I still have a vivid recollection of this Jim Burns cover. Strangely, I also recall Ian Livingstone's editorial in which he suggests that computer games can never replace tabletop RPGs (or even boardgames) for the satisfaction they provide in playing them with (or against) human beings. Nearly forty years later, I find it hard to disagree.

With issue #43 of White Dwarf (July 1983), we are well within the range of issues I remember strongly from my youth. This is the period before I'd actually subscribed to the magazine – that would come a little while later – but after I'd made it a point to pick up a new issue each month. Consequently, I still have a vivid recollection of this Jim Burns cover. Strangely, I also recall Ian Livingstone's editorial in which he suggests that computer games can never replace tabletop RPGs (or even boardgames) for the satisfaction they provide in playing them with (or against) human beings. Nearly forty years later, I find it hard to disagree.

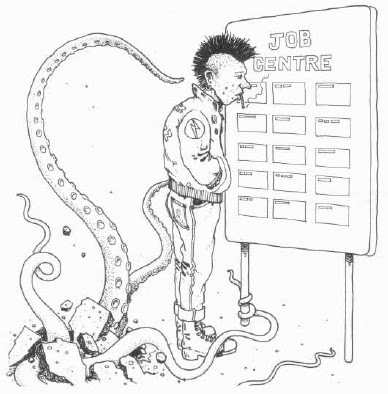

Part 2 of Marcus L. Rowland's "Cthulhu Now!" presents two mini-scenarios and one campaign outline for use in a Call of Cthulhu campaign set in the 1980s. One of these, entitled "Trail of the Loathsome Slime," would become the basis for a licensed CoC adventure published by Games Workshop at a later date. Since I never owned that particular book, I can't say how closely it hews to Rowland's original idea. I really enjoyed this article back in 1983 and it encouraged me to try my hand at modern day Call of Cthulhu.

"Open Box" reviews Warhammer in its initial release, earning 8 out of 10. I've mentioned before that I've never had the chance to look at this version of the game and now I wish I had. It's a pity that it's nigh impossible to find a copy at a reasonable price. Oliver Dickinson gives Questworld, Chaosium's alternate setting for RuneQuest, a mere 6 out of 10, which surprises me, as my (admittedly hazy) recollection is that it was more interesting than that. I shall have to re-read it sometime soon to see if I agree with Dickinson's assessment. Finally, there's a review of the play-by-mail game, The Tribes of Crane, which garners a 9 out of 10 – high praise indeed! I never got into play-by-mail games, but I'm fascinated by them, so such a positive review only piques my interest further.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" looks at a number of books, starting with a couple casting skeptical eyes on psychic and related phenomena. He follows it up with reviews of Alfred Bester's The Deceivers and The Insider by Christopher Evan. I've read the former, but I've never even heard of the latter. Go figure. "Hanufa's Little Sister" is Oliver Dickinson's final short story of Griselda. The tale includes a note that information on her further exploits can be found in Chaosium's Pavis. This is true: the boxed set released the same year as this issue includes another short story of Griselda, also written by Dickinson (though her game stats appear in Big Rubble, along with those of her associates).

"Magimart" by Lewis Pulsipher briefly discusses the ups and downs allowing the buying and selling of magic items in a D&D campaign. As with so many of Pulsipher's articles, he offers sound advice, though it's difficult, from the vantage point of the present, to appreciate it fully, since so much of what he has to say has since passed into the collective wisdom of the hobby. "Vehicle Combat" by Andy Slack, meanwhile, remains of lasting interest. It's a nice, simple system for adjudicating vehicle combat in Traveller without recourse to Striker (though it does make use of Mercenary). I had a lot of fun, thanks to this article, so it remains a favorite of mine to this day.

The centerpiece of the issue is Part 2 of Daniel Collerton's "Irilian." As with last issue, Collerton describes a single section of the city, along with an adventure set in that part of Irilian. This part focuses attention on an abbey and an inn, both of which are given complete maps and both of which figure prominently in the scenario. The remainder of the article describes on living in Irilian, with an emphasis placed on what houses look like, family arrangements, coinage, and similarly mundane but nevertheless useful features. It's another great installment in a terrific series; it remains one of the highlights of White Dwarf during the period when I was reading it.

"Happy Landings!" by Thomas M. Price is a very good three-page article for Traveller. Price looks at starport design, an overlooked aspect of Traveller in my opinion (and not just because I worked on a book concerning this topic). What makes the article especially good are the half dozen or so sample maps included with it. Traveller characters spend an awful lot of time in starports; having more examples of possible layouts is this extremely helpful to the harried referee. This was another favorite of mine. "Arms Talk" by Oliver Dickinson is a discussion of damage absorption in RuneQuest. It's a fairly dense little essay, filled with plenty of musings about RQ's combat system. At the time, I wasn't playing the game, so I paid little heed to it. Nowadays, I wouldn't give it much attention either, since the complexities of the combat system are my least favorite aspects of RuneQuest.

"And Some Came Riding" is a fun installment of "Fiend Factory," describing several new D&D monsters that make use of mounts of one type or another. I especially like the Bug Riders, insect men who make use of a variety of arthropods as riding beasts. "Bujutsu" by Graeme Davis details Japanese weapons for use by AD&D monks, which was a well worn genre of article in the gaming magazines of the '80s. Finally, there's the first appearance of the comic Gobbledigook by Bil (who, I believe, is Bill Sedgwick, who did art for Games Workshop). I loved many of White Dwarf's comics, including Gobbledigook, so it was great seeing his debut in this issue.

Issue #42 of White Dwarf is an excellent one, perhaps one of the best I ever owned. The mix of D&D, Call of Cthulhu, and Traveller material was welcome, since they were my three main RPGs back in the days of my youth. Even now, they remain among my favorites. It's a real pleasure to revisit issues like this one and I look forward to those that follow it, as I recall that many of them are just as superb as this one.

July 25, 2022

"Robot Role-Playing Game"

The "Coming Attractions" column in issue #99 of Dragon (July 1985) included an entry for a new science fiction roleplaying game entitled Proton Fire.

The entry does not specify a release date, which only makes sense, because the game was never released. Steve Winter, who worked at TSR at the time, explained that Proton Fire was in fact completed (and even playested) but that it was canceled due to a lack of enthusiasm on the part of both TSR and its distributors. Nevertheless, I still sometimes think about Proton Fire and what it might have been like, but then I am also a connoisseur of vaporware RPGs, so that should come as little surprise.

The entry does not specify a release date, which only makes sense, because the game was never released. Steve Winter, who worked at TSR at the time, explained that Proton Fire was in fact completed (and even playested) but that it was canceled due to a lack of enthusiasm on the part of both TSR and its distributors. Nevertheless, I still sometimes think about Proton Fire and what it might have been like, but then I am also a connoisseur of vaporware RPGs, so that should come as little surprise.

Pulp Fantasy Library: Pickman's Model

Though I'd read some of the stories of H.P. Lovecraft before the release of Call of Cthulhu in 1981, it was the publication of that roleplaying game that greatly accelerated my knowledge and appreciation for the works of HPL, as I suspect it was for others as well. Unless my memory is playing tricks on me, I believe the first edition of CoC includes an introduction or an essay by Sandy Petersen, in which he talks about his first encounter with Lovecraft at a tender age. As I recall it, Petersen states that the first Lovecraft tale he read was "Pickman's Model" and that it left a lasting impression on him (just as my first HPL story, "The Tomb," did for me).

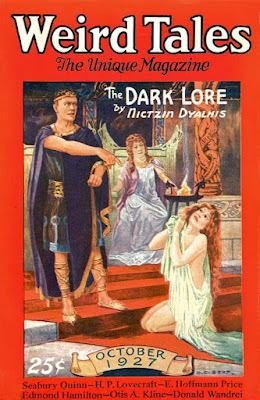

Though I'd read some of the stories of H.P. Lovecraft before the release of Call of Cthulhu in 1981, it was the publication of that roleplaying game that greatly accelerated my knowledge and appreciation for the works of HPL, as I suspect it was for others as well. Unless my memory is playing tricks on me, I believe the first edition of CoC includes an introduction or an essay by Sandy Petersen, in which he talks about his first encounter with Lovecraft at a tender age. As I recall it, Petersen states that the first Lovecraft tale he read was "Pickman's Model" and that it left a lasting impression on him (just as my first HPL story, "The Tomb," did for me). Seeing that in the pages of the Call of Cthulhu rulebook was recommendation enough for me and I quickly sought out the story. I found it in a paperback collection called The Dunwich Horror and Others. The story was every bit as memorable as Petersen had implied it would be. Like "The Tomb," it remains a favorite of mine, despite the fact that, by many measures, it's not one of Lovecraft's most well crafted stories. On the other hand, its central ideas are powerful ones and there are passages in the tale that I continue to find moving."Pickman's Model" first appeared in the October 1927 issue of Weird Tales. Like so many Lovecraft stories, it's told in the first person, in this case from the perspective of a man named Thurber, who tells his tale to yet another man, Eliot. Thurber begins by saying, "You needn't think I'm crazy, Eliot," which is rarely an auspicious beginning, particularly in a H.P. Lovecraft story. Thurber goes on to say that he had recently "begun to cut the Art Club" in order to "keep away from Pickman."

"Boston had never had a greater artist than Richard Upton Pickman," Thurber declares.

Any magazine-cover hack can splash paint around wildly and call it a nightmare or a Witches’ Sabbath or a portrait of the devil, but only a great painter can make such a thing really scare or ring true. That’s because only a real artist knows the actual anatomy of the terrible or the physiology of fear—the exact sort of lines and proportions that connect up with latent instincts or hereditary memories of fright, and the proper colour contrasts and lighting effects to stir the dormant sense of strangeness.

If that sounds a bit like Lovecraft himself speaking, you're probably correct in your assessment. Much of what Thurber says about art in "Pickman's Model" echoes Lovecraft's own sentiments at the time. These passages are fascinating if you're interested in the evolution of HPL's own thought, but they sometimes get in the way of the narrative.

Pickman, we learn, is an artist of the "morbid" and the "weird," whose works had "repelled" the upstanding members of the Boston arts scene. Thurber, at least initially, was more open-minded in his assessment. Indeed, he begins to spend a great deal of time with Pickman.

Before long I was pretty nearly a devotee, and would listen for hours like a schoolboy to art theories and philosophic speculations wild enough to qualify him for the Danvers asylum. My hero-worship, coupled with the fact that people generally were commencing to have less and less to do with him, made him get very confidential with me; and one evening he hinted that if I were fairly close-mouthed and none too squeamish, he might shew me something rather unusual—something a bit stronger than anything he had in the house.

Remember that, at the beginning of the story, Thurber confessed to Eliot that he had started to "keep away from Pickman." At this point in his tale, though, he was instead the painter's friend and confidante. What, then, could have effected this change in his attitudes?

Pickman lives in the dilapidated North End of Boston, since any "sincere" artist would "put up with the slums for the sake of the massed traditions."

God, man! Don’t you realise that places like that weren’t merely made, but actually grew? Generation after generation lived and felt and died there, and in days when people weren’t afraid to live and feel and die.

Again, this is clearly Lovecraft speaking through the mouth of Thurber, but I've long had sympathy for his preference for organic growth over rational planning when it comes to many human endeavors, so I'll let it pass. Regardless, Pickman eventually reveals to Thurber that he has "another studio" elsewhere "where I can catch the night-spirit of antique horror and paint things that I couldn't even think of in Newbury Street." This studio is located in a cellar near Copp's Hill Burying-Ground and it's here that he keeps his most shocking paintings, which Thurber sees for the first time.

There’s no use in my trying to tell you what they were like, because the awful, the blasphemous horror, and the unbelievable loathsomeness and moral foetor came from simple touches quite beyond the power of words to classify. There was none of the exotic technique you see in Sidney Sime, none of the trans-Saturnian landscapes and lunar fungi that Clark Ashton Smith uses to freeze the blood. The backgrounds were mostly old churchyards, deep woods, cliffs by the sea, brick tunnels, ancient panelled rooms, or simple vaults of masonry. Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, which could not be many blocks away from this very house, was a favourite scene.

The madness and monstrosity lay in the figures in the foreground—for Pickman’s morbid art was preëminently one of daemoniac portraiture. These figures were seldom completely human, but often approached humanity in varying degree. Most of the bodies, while roughly bipedal, had a forward slumping, and a vaguely canine cast. The texture of the majority was a kind of unpleasant rubberiness. Ugh! I can see them now! Their occupations—well, don’t ask me to be too precise. They were usually feeding—I won’t say on what. They were sometimes shewn in groups in cemeteries or underground passages, and often appeared to be in battle over their prey—or rather, their treasure-trove. And what damnable expressiveness Pickman sometimes gave the sightless faces of this charnel booty! Occasionally the things were shewn leaping through open windows at night, or squatting on the chests of sleepers, worrying at their throats. One canvas shewed a ring of them baying about a hanged witch on Gallows Hill, whose dead face held a close kinship to theirs.

Thurber is most impressed by how realistic these paintings are, as if Pickman had not conjured them from his imagination but rather had painted them from life. That is, of course, the "surprise" twist of "Pickman's Model" and I hope no one will be aggrieved at my having revealed it here. The story is nearly a century old at this point and, besides, Lovecraft telegraphs the tale's ultimate revelation several times before explicitly presenting it.

At any rate, it's not the conclusion of the story that matters so much as the ideas it presents and the manner in which Lovecraft does so. Lovecraft is deeply concerned with realism in art, which he considers to be essential to its power. This is why he spends so much time in his stories set the scene, enumerating seemingly insignificant details, and grounding his whole narrative in elaborate histories. One might justifiably quibble with his execution of this approach in some instance, but his reasons for doing so are quite sound, given his interest in literary realism. "Pickman's Model" is by no means a flawless masterpiece, yet it points the way forward for Lovecraft's later career and, for that reason alone, deserves one's attention.

July 21, 2022

Frodo Was a 2nd-Level Fighter

As I noted in my examination of issue #38 of White Dwarf (January 1983), Lewis Pulsipher provided AD&D game statistics for the members of the Fellowship of the Ring. Here they are:

Let's take a brief look at these stats, starting with Gandalf, who is an 8th-level cleric with a slightly modified list of spells. I find that fascinating, especially in light of Gary Gygax's comment in Dragon – can anyone recall the specific issue? – that Gandalf was not a magic-user but a cleric (and a fairly low-level one at that). It's also noteworthy that Pulsipher lists him as a "Man" rather than a Maia.

Let's take a brief look at these stats, starting with Gandalf, who is an 8th-level cleric with a slightly modified list of spells. I find that fascinating, especially in light of Gary Gygax's comment in Dragon – can anyone recall the specific issue? – that Gandalf was not a magic-user but a cleric (and a fairly low-level one at that). It's also noteworthy that Pulsipher lists him as a "Man" rather than a Maia. Aragorn is described as a "ranger-paladin." Whether that's meant to represent a multi/dual class is open to interpretation, since Pulsipher only indicates a single level (7th) for the character. It's an odd, though understandable, way to represent the character, since Aragorn does demonstrate a number of abilities that are akin to those of an AD&D paladin. On the other hand, the ranger class only exists as a way to represent Aragorn as a Dungeons & Dragons character. That Pulsipher didn't think the class adequate to the task is intriguing.

Boromir is just a straight-up fighter, which makes perfect sense. The same is true of Gimli and, aside from his relatively low level, I don't think anyone could find fault with this interpretation. Of course, Legalos (also a fighter) is similarly low level, so there's likely a method to Pulsipher's madness here.

The hobbits are interesting. Only Frodo is a fighter, while Sam, Pippin, and Merry are all thieves. I can see a logic to Sam's being a thief, given his skill at sneaking about. Likewise, Merry makes sense too; he did, after all, help defeat the Witch-King of Angmar with perhaps one of the greatest backstabs in all of fantasy literature. Pippin, though, seems like he ought to be a fighter. He showed considerable skill in battle, eventually defeating a troll. Likewise, he later became Thain of the Shire, a largely military office.

Attempting to provide game statistics for literary characters, as Dragon did in its "Giants in the Earth" series, is always a fraught endeavor. While inspired by literature, D&D was never intended to emulate its specific. The game's character classes (and their abilities) generally have game-specific origins and purposes. Consequently, definitively pronouncing that any literary belongs to a particular class or is of a particular level is never going to be wholly satisfying. That said, I think Lewis Pulsipher did a fair job in this case, especially in light of his goal of using The Lord of the Rings as a way to introduce newcomers to Dungeons & Dragons. I can quibble about the fine details, but not the general direction of his adaptation.

July 20, 2022

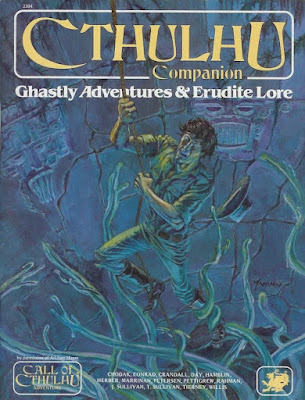

Retrospective: Cthulhu Companion

I've written before about my fondness for the concept of companion volumes to roleplaying games. By "companion," I don't simply mean a rules supplement, though many RPG companions do include augmented, expanded, and/or new rules. Rather, a companion – or a good companion, at any rate – isn't focused solely on the mechanical aspects of a game; neither does it consist entirely of "fluff." Instead, it's a buffet of options, ideas, and inspiration for players and referees alike, particularly those who've been playing a game for some time.

I've written before about my fondness for the concept of companion volumes to roleplaying games. By "companion," I don't simply mean a rules supplement, though many RPG companions do include augmented, expanded, and/or new rules. Rather, a companion – or a good companion, at any rate – isn't focused solely on the mechanical aspects of a game; neither does it consist entirely of "fluff." Instead, it's a buffet of options, ideas, and inspiration for players and referees alike, particularly those who've been playing a game for some time. The first such companion I ever owned was 1983's Cthulhu Companion, subtitled "Ghastly Adventures & Erudite Lore." Released two years after the publication of the first edition of Call of Cthulhu. CoC was – and is – one of my favorite RPGs. After my initial purchase of it in 1981, I played the heck out of it with my friends. Consequently, I was more than ready for this companion when it was released. I was eager for additions and expansions to the original game, not to mention inspiration for my own adventures. I found all of that and more in this book.

Cthulhu Companion begins with a brief overview of the changes appearing in the upcoming second edition of the rulebook. The changes are quite minor, the most significant being that the characteristic Charisma is replaced by Appearance, for reasons that are never explained. At the time, I simply accepted this change, which was subsequently employed in several other Basic Role-Playing variants, like Pendragon. Nowadays, I find it a bit odd. If ever there were a game where a character's physical appearance should matter little, it's Call of Cthulhu. All the rules changes presented in Cthulhu Companion are small and that's one of the things I've long admired about CoC: until very recently, every edition of the game and its support materials were mechanically compatible without almost any effort.

Highlights of the companion are "The Cthulhu Mythos in Mesoamerican Religion" and "Further Notes on the Necronomicon." Both of these faux academic articles try to contextualize the entities of Lovecraft and his imitators within real world cultures and mythologies. The former takes a cue from Zealia Bishop's "The Mound" (ghostwritten by HPL) and focuses primarily on Aztec religion, while the latter casts a broader net, delving into Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and Arabic legendry. I love these sorts of articles, which provide excellent pointers for how to make the Cthulhu Mythos feel more "real" and grounded. I read and re-read both of these many, many times in my younger days.

Also included are lots more details about prisons in the 1920s, along with a large list of new insanities and Mythos beings. These might be called the "bread and butter" of companion volumes like this, since they're useful to any referee – I mean Keeper of Arcane Lore – regardless of the kind of campaign he is running. Of particular interest to me, both then and now, are the inclusion of deities from the works of Clark Ashton Smith. I've long felt that one of the strengths of Call of Cthulhu is that it's infinitely capable of expansion beyond the works of Lovecraft himself. Indeed, I think the game is improved by occasionally shifting its focus elsewhere, lest it become too monomaniacal in its devotion to the Lovecraftian canon (however defined).

Of course, no companion would be complete without adventures. Cthulhu Companion includes four, ranging from the brief to the lengthy. Each of them is unique and illustrates a different aspect of Call of Cthulhu. For example, "Paper Chase" is a short scenario that brings the investigators into contact with a a Mythos being that is not entirely antagonistic – an unusual occurrence! "The Mystery of Loch Feinn," meanwhile, is an example of couching an old legend in Mythos terms. "The Rescue" is a "mundane" horror scenario involving non-Mythos creatures (werewolves), while "The Secret of Castronegro" imagines what a Mythos tale might be like if set in the American Southwest rather than Lovecraft's New England. Even if not used as-is, all the adventures contain plenty of ideas and inspiration the Keeper can use in crafting his own.

Cthulhu Companion is a classic Chaosium product, filled with plenty of imagination and inspiration. Aside from the original boxed set, this is probably the Call of Cthulhu product from which I got the most use back in the day. Even now, paging through, thoughts of a campaign centered around a subterranean expedition in search of blue-litten K’n-yan, red-litten Yoth, and black, lightless N'kai – all thanks to the little hints about each mentioned in the Mesoamerican Religion article. It's precisely for that reason that I'm such a big fan of companion books and takes such pleasure in them. Here's hoping we might see more books of this sort in the future!

July 19, 2022

White Dwarf: Issue #42

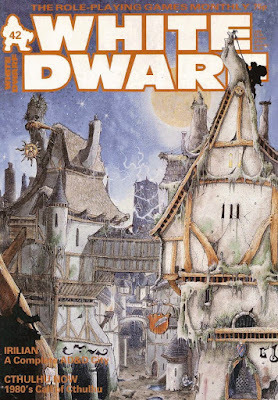

Issue #42 of White Dwarf (June 1983) is one of a handful of issues for which I have particularly strong memories, in large part because of the two articles that feature on the cover: "Irilian" and "Cthulhu Now!" The magnificent cover by John Blanche also likely played a role, as it nicely incorporates the historical, creepy, and goofy elements I so strongly associate with British fantasy in the '70s and '80s (and that Warhammer honed to perfection). Ian Livingstone's editorial notes that he'd received a certain amount of what he describes as "hate mail" concerning the changes to the magazine's appearance that began with issue #39. Long-time readers apparently preferred the "quaint" look of the earlier issues. As a proud hater of change, this does not surprise me to say the least.

Issue #42 of White Dwarf (June 1983) is one of a handful of issues for which I have particularly strong memories, in large part because of the two articles that feature on the cover: "Irilian" and "Cthulhu Now!" The magnificent cover by John Blanche also likely played a role, as it nicely incorporates the historical, creepy, and goofy elements I so strongly associate with British fantasy in the '70s and '80s (and that Warhammer honed to perfection). Ian Livingstone's editorial notes that he'd received a certain amount of what he describes as "hate mail" concerning the changes to the magazine's appearance that began with issue #39. Long-time readers apparently preferred the "quaint" look of the earlier issues. As a proud hater of change, this does not surprise me to say the least.The issue kicks off with the first part of "Cthulhu Now!" by Marcus L. Rowland. The purpose of the article (and the series it inaugurates) is to provide rules additions and expansions to make playing Call of Cthulhu in the 1980s possible. This issue's installment focuses on new skills, firearms, and careers (including rock musician). While I am no longer as enamored of the idea of playing Call of Cthulhu in the present day, I simply adored this article in my youth.

"... to Catch a Thief …" by Graham Staplehurst is an article devoted to crime prevention, detection, and perpetration in Traveller. It consists entirely of new technological items, such as alarms, locks, IDs, and personal gear of various sorts. The article is fine for what it is, though, even in 1983, I felt that the last thing Traveller – and, by extension, most SF RPGs – needed was yet more technological items. "Shamus Gets a Case" by Oliver Dickinson is another tale set in New Pavis featuring Griselda. Like its predecessors, this is a fun story that offers a unique spin on Glorantha's most famous city and its denizens.

"... to Catch a Thief …" by Graham Staplehurst is an article devoted to crime prevention, detection, and perpetration in Traveller. It consists entirely of new technological items, such as alarms, locks, IDs, and personal gear of various sorts. The article is fine for what it is, though, even in 1983, I felt that the last thing Traveller – and, by extension, most SF RPGs – needed was yet more technological items. "Shamus Gets a Case" by Oliver Dickinson is another tale set in New Pavis featuring Griselda. Like its predecessors, this is a fun story that offers a unique spin on Glorantha's most famous city and its denizens. "Open Box" begins with a review of SoloQuest 3: The Snow King's Bride for RuneQuest. The reviewer, Oliver Dickinson, has some minor quibbles with the solo scenario but is otherwise quite pleased with it, giving it a score of 8 out of 10. Marcus Rowland is similarly pleased with two new Fighting Fantasy books, The Citadel of Chaos (9 out of 10) and The Forest of Doom (10 out of 10). I have a particular fondness for The Forest of Doom myself, so this pleases me. On the other hand, FASA's Grav Ball – a game I only know from old advertisements in Dragon and elsewhere – gets a mere 4 out of 10. Neither The Morrow Project nor its scenario, Liberation at Riverton, do much better, earning 5 and 6 out of 10 respectively.

In his "Critical Mass" column, Dave Langford offers his opinions on the nominees and winners of various science fiction and fantasy awards, including the Hugos. I remember a time when I not only recognized but had read many of the books on such awards lists. Nowadays, like so much else, I have no knowledge of them. "Castles in the Air" by Lewis Pulsipher is a short but interesting article in which he muses about why dungeons might exist in a fantasy setting. In the process, he implicitly raises the equally relevant question of why so many fantasy worlds resemble copies of medieval Europe, despite the presence of magic and monsters that would, for example, obviate the utility of traditional castles. "Careers in Traveller" by Marcus Rowland presents the code for a computer program that will randomly generate Traveller characters – a staple of 1980s gaming magazines.

Daniel Collerton's "Irilian" is the first part of a six-part series describing the titular city of Irilian. Each part includes a scenario that introduces a new aspect or portion of the city, along with additional information about Irilian's society and culture. The first part, in this issue, is mostly an overview of the city, detailing its laws, calendar, diseases, religion, and so on. What stands out is that Collerton makes use of Old English words to name the people and places of Irilian, which gives it a unique flavor. I adored this article in my youth, along with its sequels. I read and re-read them many times and even placed Irilian into one of my old campaign settings.

Phil Masters continues his "Inhuman Gods" series, this time giving us information on the deities of norkers, svirfneblin, and trolls, among others. "Rune Rites" presents "Horses" by Graham Cobley, a collection of RuneQuest game statistics for different breeds of horses. In principle, I've long liked the idea of such details; in practice, though, it's rarely been the case that any player has cared as much as I did. "The Sorceror's [sic] Spell Book" by Gary and Terry Saul is a fairly typical collection of new spells for use with D&D. The only truly memorable one is Valin's Total Inversion, which kills its target by turning him inside out. The spell was quite infamous in many of the gaming circles in which I moved back in my youth and understandably so.

It's difficult for me to be objective about this particular issue, since it was one of my favorites of old. "Irilian" remains the issue's centerpiece and I think it holds up quite well, even after all these years. I look forward to re-reading the next five issues, which further develop the city and its inhabitants.

July 18, 2022

Grognard's Grimoire: Rashthul

A deadly pest of the deserts of sha-Arthan is the rashjalum, a flying, carnivorous insect that dwells in enormous hives. Each hive has a complex society under a single "high queen," protected by several dozen "war queens" that command swarms of insects that search for threats and food. A war queen typically parasitizes a desert-dwelling animal, such as the barkoa land-crab, hijacking its nervous system and mutating its body to serve as a mobile sub-hive from which to attack foes and defend her high queen.

When a war queen parasitizes a Man, the result is a rashthul. Its bones unpredictably mutated into a chitinous exoskeleton and its brain consumed, a rashthul has no will of its own. It exists only as a vehicle for these terrible insects, roaming the deserts of the True World with no purpose other than to destroy whatever its controlling war queen commands.

AC 4 [14], HD 4+1** (19hp), Att 2, 3, or 4 × weapon (1d6 or by weapon), THAC0 15 [+4], MV 90’ (30’), SV D10 V11 P12 B13 S14 (4), ML 10, XP 275, NA 1d6 (2d6), TT Nectar

Immunities: Immune to effects that affect living creatures (e.g. poison). Immune to mind-affecting or mind-reading spells. Half-damage: Suffer only half-damage from sharp and/or edged weapons. Weapons: 4×1-handed, 2×1-handed and 1×2-handed, or 2×2-handed.Attack multiple opponents: Up to 3 per round.Rashjalum swarm: Automatically damages opponents within a 10' × 10' area surrounding the rashthul: 2hp per round if wearing armor, 4hp without.Warding off: A brandished torch or other source of flame and/or smoke causes the swarm to retreat into the body of the rashthul. Nectar: 1d4 tamu of medicinal nectar may be found within each rashthul's body. Properly remedied, each tamu heals 1d6 hit points if consumed in its entirety. The presence of this nectar gives the rashthul an oddly sweet smell, detectable within 60'. A rashthul by Zhu Bajie

A rashthul by Zhu Bajie

Dragonlance is Coming

July 17, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: Kolchak: The Night Stalker

Once again, I stretch the terms "pulp," "fantasy," and perhaps even "library" beyond the breaking point in an effort to write about an entertainment that nevertheless exercised an influence over Dungeons & Dragons. In this particular case, I offer no apologies, since I've been intending to write (again) about the 1974–1975 television series, Kolchak: The Night Stalker and this space seemed as good a place to do so as any. The show was, along with

Star Trek

, a favorite of mine as a child – influenced, in both cases, by my paternal aunt, who had a love for things scary and science fictional, hence her also taking me to see Star Wars in June 1977.

Once again, I stretch the terms "pulp," "fantasy," and perhaps even "library" beyond the breaking point in an effort to write about an entertainment that nevertheless exercised an influence over Dungeons & Dragons. In this particular case, I offer no apologies, since I've been intending to write (again) about the 1974–1975 television series, Kolchak: The Night Stalker and this space seemed as good a place to do so as any. The show was, along with

Star Trek

, a favorite of mine as a child – influenced, in both cases, by my paternal aunt, who had a love for things scary and science fictional, hence her also taking me to see Star Wars in June 1977. In the early part of this century, a friend gave me a DVD collection of the entire series, whose twenty episodes I've regularly watched and re-watched in the years since. Sadly, the collection was a poor one. The video transfers were grainy and the DVDs themselves were double-sided. It's a cheap, money-saving measure on the part of the manufacturer that all but ensures the discs will eventually become smudged and scratched, as mine eventually did. But I loved the series enough that I suffered through the slow degradation of my discs.

Fortunately, in 2018, a company called Kino Lorber released a high definition restoration of the original 1972 TV movie, also called The Night Stalker, followed soon thereafter of a similar restoration of its 1973 sequel, The Night Strangler. These were amazing pieces of work in every possible way and I hoped the company might eventually turn its attention to the television series as well. My wish was granted in the fall of 2021, when Kolchak: The Night Stalker received a similarly lavish HD restoration. It took me a while to get my hands on a copy, but I eventually did, which is why I wanted to write this post.The original TV movie was based on an unfinished novel by Jeff Rice and adapted by Richard Matheson (best known for I Am Legend and his work on Roger Corman's various Edgar Allan Poe movies from the early 1960s). The movie was, in turn, directed by John Llewellyn Moxie (who'd directed several films starring Christopher Lee) and produced by Dan Curtis of Dark Shadows fame. Both it and its sequel were presented as straight-up horror movies, albeit with a "crusading reporter" edge that was very relevant to post-Watergate America.

By contrast, the television series was an odd bird, equal parts horror, comedy, and social commentary. The precise mix of these three elements varied from episode to episode – and sometimes scene to scene – and that's probably why, as a child, I had such a fondness for the show. Though, like most children, I enjoyed being frightened, I nevertheless appreciated the breaks from terror afforded by Darren McGavin's comedic hijinks (and those of the show's terrific guest stars, like Jim Backus, Phil Silver, Larry Storch, and Keenan Wynn, among many, many others). As I've said previously, the show was scary but not too scary.

The series only had twenty episodes before it was canceled. Its cancellation was largely the result of Darren McGavin's dissatisfaction with its direction. While many of the people involved with the show wanted it to be more serious and genuinely frightening, McGavin preferred a lighter, more comedic tone. There were thus many behind-the-scenes tussles between the show's star and its production staff regarding the content and feel. This background tension sometimes gives episodes a schizophrenic quality. At other times, though, I think it actually contributes to the success of certain episodes. I also think it's fair to say that Kolchak: The Night Stalker is an "uneven" series, whose high points nevertheless more than make up for its lows.

Among its high points are:"The Zombie," which presents a frightening, Voodoo-inflected version of the zombie (that Holmes references in his D&D Basic Rules)"The Devil's Platform," in which Tom Skerrit plays a politician who's sold his soul to the Devil."The Spanish Moss Murders," Forbidden Planet's creatures from the id meet Cajun folklore (and the inspiration for a foe in my Dwimmermount campaign)"Horror in the Heights," the episode that introduced Gary Gygax to the rakshasa"Chopper," a story of a headless motorcycle writer, written by Robert ZemeckisThat said, I enjoy even the less well regarded episodes, because many of them contain interesting characters, situations, and characters. And, of course, Darren McGavin is fun to watch. One of the pleasures of the Kino Lorber remastered collection is that each episode includes commentary, often by film and television historians, who shed light on aspects of the show's production and influence. It's fascinating stuff if, like me, you enjoy learning about all the work that goes into making popular entertainment. Likewise, it's remarkable to discover just how many individuals who worked on Kolchak: The Night Stalker would later go on to success later in their careers.

I may still write further posts on the series in the weeks to come, but, now that I've had the chance to gush a bit about it today, I can resume making more "traditional" posts in this series next week. Thanks for your indulgence.

July 6, 2022

More Postal Humor

Since my previous post on this topic was well received, here are three more examples of the humorous fake envelopes included on the White Dwarf letters page, from issues #36, #37, and #38 respectively. While the inspirations for the last two envelopes are obvious to me, the first one eludes me. Can any readers help me make sense of it?

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers