James Maliszewski's Blog, page 101

August 23, 2022

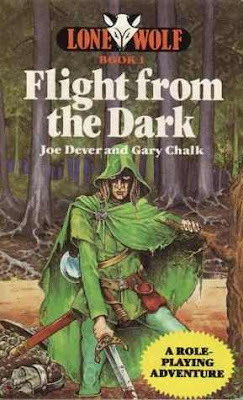

Retrospective: Lone Wolf

Lately, I've had a great deal of interest in solo fantasy gaming. Though there were plenty of early examples, starting with Buffalo Castle in 1976, the trend toward solitaire adventures really started to pick up steam in the early 1980s, with the publication of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. The success of that book – and the Fighting Fantasy series more generally – showed that there was definitely a large audience for solo gaming and it wasn't long before innumerable knock-offs and imitators appeared on the scene.

Lately, I've had a great deal of interest in solo fantasy gaming. Though there were plenty of early examples, starting with Buffalo Castle in 1976, the trend toward solitaire adventures really started to pick up steam in the early 1980s, with the publication of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. The success of that book – and the Fighting Fantasy series more generally – showed that there was definitely a large audience for solo gaming and it wasn't long before innumerable knock-offs and imitators appeared on the scene.

While some of these imitators weren't very good, a few of them stand out in retrospect as having brought something genuinely original and imaginative to the table. Among these is the Lone Wolf series by Joe Dever and Gary Chalk. Like Steve Jackson's Sorcery!, Lone Wolf was a series of connected gamebooks, in which the reader takes on the role of a single character whose adventures form a single narrative. In each of its five books (published over the course of 1984 and '85), the narrative advances toward its conclusion and the character along with it.

The character the reader plays is Silent Wolf, the last surviving member of the Kai, a monastic order of warriors known for their remarkable skills and disciplines. At the start of the first book in the series, Flight from the Dark, the Kai monastery is attacked by flying creatures sent by the Darklords, the eternal enemies of the lands of Sommerlund and Durenor. Silent Wolf only survives because, while his masters and fellow initiates are preparing for a great celebration, he is in a nearby forest collecting firewood, as punishment for his inattention in his lessons. When he returns, it is too late to stop the slaughter and Silent Wolf has no choice but to seek out the king of Sommerlund to warn him of the Darklords return.

In broad outline, the narrative of the Lone Wolf series is broadly similar to that of Sorcery! and indeed of many fantasy novels, with the reader playing a pivotal role in staving off an invasion by evil forces. That's no knock against it, since it makes it immediately accessible to anyone with an interest in fantasy, especially the younger readers for whom this series was likely written. What sets it apart, at least from the perspective of other solitaire gamebooks, is its approach to advancement, which substitutes for more complex experience systems in RPGs.

The Kai possess knowledge of certain disciplines – quasi-magical abilities like healing, mindshield, and sixth sense, that aid him in his quest. To begin, Silent Wolf only possesses a few of these disciplines. However, as he progresses from one book to another in the series, his mastery of the disciplines increases and the reader may select more disciplines to learn. By the end of the series, then, Silent Wolf is much more powerful – and versatile – in his abilities. This is important, as the challenges he faces increase as well. This is another way in which the Lone Wolf series simply but enjoyable replicates the escalating nature of D&D-style fantasy roleplaying games.

Much like the Fighting Fantasy books, Lone Wolf's game mechanical elements are quite simple. There are only two ability scores, Combat Skill and Endurance, both of which are employed primarily when engaged in combat against enemies. Combat is not complicated, but it's more interesting than one might expect in a gamebook. Rather than relying on random rolls, there's a random number table that looks like a checkerboard whose squares all contain a number from 0 to 9. The reader is directed to close his eyes and point a pencil at the table, with the result being wherever the pencil's point lands. The result is then used in conjunction with the ratio of the Combat Skill ratings of both attacker and defender to generate a result. It's not a perfect system by any means, especially since, after a while, one becomes familiar with the layout of the random number table, even when one's eyes closed. However, as presented, the system isn't wholly predictable, which means combat can turn unexpectedly deadly if one is not careful.

All in all, the Lone Wolf series is fairly fun. Each book in the original series of five – there were many more published after its conclusion – has a large number of entries, which opens up a good range of choices to the reader. That's important in solitaire adventures, since they're necessarily more limited than adventures played with actual human beings. Lone Wolf is helped, too, by the evocative artwork of Gary Chalk. The illustrations nicely set the tone of the whole series and blew me away when I first saw them. Like the Russ Nicholson art of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain or John Blanche's illustrations in Sorcery!, Chalk's pieces in Lone Wolf gave these books a unique look unlike anything produced in the USA at the time. British fantasy of the early 1980s was truly remarkable and the Lone Wolf series is yet another example of why.

A Thief, A Reaver, A Slayer, A Corsair ...

From "Thrud the Barbarian" by Carl Critchlow (White Dwarf #47, November 1983):

Cursed Scroll

August 22, 2022

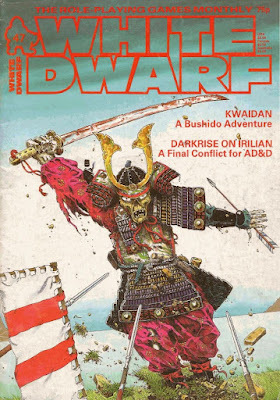

White Dwarf: Issue #47

White Dwarf regularly featured very striking covers. Whether because of their style, subject matter, or both, I generally can't help but find them much more compelling than those of other gaming magazines from the same period of time. The cover of issue #47 (November 1983) is no exception to this, with its undead samurai as painted by Gary Chalk, who's probably best known for his work on the Lone Wolf series of gamebooks (about which I'll talk more later this week).

White Dwarf regularly featured very striking covers. Whether because of their style, subject matter, or both, I generally can't help but find them much more compelling than those of other gaming magazines from the same period of time. The cover of issue #47 (November 1983) is no exception to this, with its undead samurai as painted by Gary Chalk, who's probably best known for his work on the Lone Wolf series of gamebooks (about which I'll talk more later this week). "The Demonist" by Phil Masters is a new character class for use with AD&D, following in the footsteps of the demon summoning rules for RuneQuest presented in the previous three issues. The class is basically a variant (evil only) cleric, with a unique spell list, including some original spells, like soul shield and summon imps. New character classes – or "NPC classes," if it's published in the pages of Dragon – have been a staple of the hobby since 1974. Most of them aren't especially interesting, so Masters deserves some credit for creating one that's not dull. That said, I'm not sure there's much need for the demonist as a distinct class, when simply creating new spells for evil clerics would suffice.

"Open Box" reviews four products this month, starting with FGU's Privateers and Gentlemen, which earns 9 out of 10 – much higher than I would have expected. The Asylum and Other Tales also receives 9 out of 10, while Starfleet Battles Supplement #1 is rated 7 out of 10. Big Rubble, on the other hand, gets a fairly nuanced rating: 10 at best, much 8–9, some scenarios 5–6. Nuanced ratings is nothing new to White Dwarf. Many ratings are divided between presentation, rules, playability, and complexity, with a single overall rating for the entire package. This is the first time, though, that I can recall seeing the "overall" rating (which is what I usually report in my posts) broken up in this way.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" reviews Asimov on Science Fiction, a nonfiction book in which Isaac Asimov offers his thoughts and opinions about the genre and its practitioners. Langford's opinion of the book is mixed. Much of it is clear, lucid, and sensible. However, Asimov's own prejudices and his incessant self-promotion mar what might have otherwise been a solid tome. Fond though I am of much of Asimov's oeuvre, I find it difficult to disagree with Langford's assessment. "Zine Scene" by Mike Lewis is the inaugural column devoted to gaming fanzines. Lewis introduces himself to the reader, along with a handful of 'zines he thinks worthy of mention.

"Extracts from the Travels of Tralk True-Eye" by Ian Bailey presents details and game stats for several types of goblins for use with RuneQuest. The goblins are imaginative and varied, which is nice, though I'm not sure how well they'd fit into Glorantha. Mind you, I often forget that White Dwarf regularly published "generic" RQ articles that were not tied to Glorantha and this appears to be another of them. I suppose it's a testament of how ingrained Glorantha is to my own conception of RuneQuest that I even think to ponder questions like this. "Aliens" by Phil Masters presents two new non-human species for use with Traveller: the crustacean-like Phulgk'k'k'k and the small ape-like Ghashruan.

The conclusion to Daniel Collerton's "Irilian" gives readers a two-page color map of the entire city. Irilian's main buildings are keyed but, to make full use of it, one must possess the previous five issues of White Dwarf. Accompanying the map is the final part of the six-part adventure, "The Rising of the Dark," which takes place within the city's walls, along with random encounter tables and information on civil and religious law. It's a terrific end to a terrific series of articles. "Irilian" was what finally convinced me to subscribe to White Dwarf after picking up single copies of it for years. That likely explains the fondness I have for the whole series and the city it depicts.

"Rune Rites" presents two very short articles for use with RuneQuest. The first, "Daily Health" by Paddy Barrow is a very odd one. It's a set of random tables to determine "how a player character feels on a certain day." Sub-tables are used if a character feels particularly good or bad, with game mechanical effects coming into play. Perhaps this might be useful on occasion, but it strikes me as a perfect example of the randomness fetishism that frequently afflicts long-time gamers. Much better is Dave Morris's "Force of Will," which codifies a system for measuring a character's ability to resist debilitating/demoralizing effects. The system is simple and easy to use; it makes a for a consistent alternative to the haphazard way RQ used to handle this sort of thing.

"Kwaidan" by Oliver Johnson and Dave Morris is a nifty little adventure scenario for Bushido. As its title suggests, it presents a ghost story set in feudal Japan. It's quite well done, with detailed NPCs, maps of a village, a monastery, and a manor house, and of course the ghosts wreaking havoc in the region. I haven't had the chance to play Bushido in years; reading "Kwaidan" makes me wish I were. "Treasure Chest" presents a mini-scenario based around a couple of weird magic items, including the "Dorianic Portrait," while "Mini-Monsters" offers five small monsters for use with D&D. The issue concludes with the latest installments of "Thrud the Barbarian" and "The Travellers," the former of which is especially amusing.

As I alluded to earlier, this issue comes from the period when I was reading White Dwarf religiously, as a companion and counterpoint to Dragon, to which I was also subscribing. Consequently, I have a lot of affection for these issues. At the same time, it's obvious in retrospect that White Dwarf was changing – becoming slicker, more professional, and diversifying its content. In addition, Game Workshop was itself changing and those changes would soon enough impact White Dwarf itself. This knowledge doesn't adversely affect my delight in re-reading issues like this one, but it does remind that Golden Ages rarely last long, no matter how great their glory.

"Ya Don't Tug on Superman's Cape"

As I'm sure readers of this blog already know, "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" was the name of Gary Gygax's regular column in the pages of Dragon. It was here that he would share previews of upcoming AD&D rules additions and changes, as well as offer his opinions on various topics of the day. Those opinions were often controversial, particularly when they pertained to the "right" way to play Dungeons & Dragons and generated a lot of pushback in the letters pages to Dragon. In retrospect, I wonder if that wasn't part of their point.

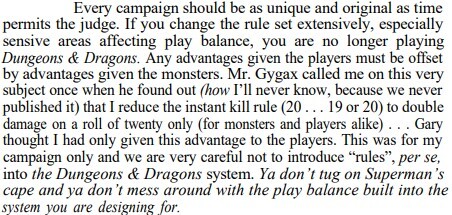

The column that appeared in issue #27 (July 1979) is quite unusual, because Gygax turns it over Bob Bledsaw of Judges Guild. Bledsaw uses the space to offer up a "personal opinion," entitled "What Judges Guild Has Done for Dungeons & Dragons." It's a fairly interesting read in its own right, but there's a short section toward the end of the piece that I want to highlight in this post.

I find it remarkable that, while Bledsaw praises uniqueness and originality in one's own campaign, he also suggests that rules changes, especially those relating to "play balance," run the risk of changing the game so much that one is no longer playing D&D. This is the position Gary Gygax himself advanced in many of his "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" columns and elsewhere. Agree or disagree, there's a logic to it and I suspect that Bledsaw, whose company produced official D&D (and, later, AD&D) materials under license from TSR, knew that this was a line he had no choice but to toe.

I find it remarkable that, while Bledsaw praises uniqueness and originality in one's own campaign, he also suggests that rules changes, especially those relating to "play balance," run the risk of changing the game so much that one is no longer playing D&D. This is the position Gary Gygax himself advanced in many of his "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" columns and elsewhere. Agree or disagree, there's a logic to it and I suspect that Bledsaw, whose company produced official D&D (and, later, AD&D) materials under license from TSR, knew that this was a line he had no choice but to toe.After that, Bledsaw then gives an example of when Gygax corrected him regarding rules changes he was using in his own campaign. This concerned the "instant kill rule (20 … 19 or 20)." What's he talking about here? No edition of D&D with which I am familiar has an instant kill rule, let alone the one he seems to describe. On the other hand, Empire of the Petal Throne does and the rule Bledsaw mentions seems almost identical to it. Is this the rule Bledsaw meant? Had he imported the EPT rule into his home campaign? If so, why did Gygax care? I understand that Gary strongly disapproved of critical hits, which is fair. However, if Bledsaw was using them in his home campaign, what difference did it make? So long as he wans't importing them into Judges Guild D&D products – and he says he was not – I don't see why Gygax should "call [him] on this very subject."

Have I misread what Bledsaw is saying?

Another View of Orcus

While issues 44, 45, and 46 of White Dwarf offered up rules for demon summoning in RuneQuest, issue 20 of Dragon (November 1978) did the same for Dungeons & Dragons, with an article entitled "Demonology Made Easy: How to Deal with Orcus for Fun and Profit" by Gregory Rihn. The article is quite interesting in its own right, but what immediately stands out about it is the following illustration that accompanies it:

That's Orcus, the Demon Prince of Undead, as drawn by Dave Trampier. So far as I can recall, this is the first (and only?) time Trampier ever drew Orcus. The rendering doesn't completely match the demon prince's description in either Eldritch Wizardry or the Monster Manual – his ram's horns, for example, are absent – but I like it nonetheless. Along with Dave Sutherland, Tramp is one of the artists whose work defines D&D for me, so it's always a joy when I discover a new piece of his that I'd previously not seen.

August 21, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Cold Gray God

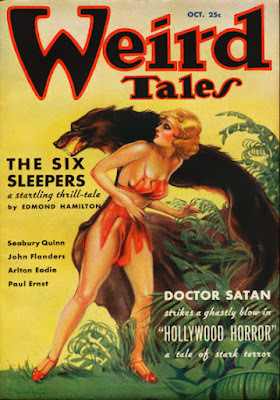

Though C.L. Moore is probably best known for her stories of the swordswoman Jirel of Joiry, it's her tales of interplanetary smuggler Northwest Smith that I've long found most appealing. Smith debuted in the November 1933 issue of Weird Tales and, over the course of the next six years, appeared in a dozen more stories in the Unique Magazine and elsewhere. Like adventures of John Carter and other early science fiction, these yarns are now wholly improbable, based as they are on incomplete or just plain erroneous science. They're also a lot of fun, filled with memorable characters and exciting situations.

Though C.L. Moore is probably best known for her stories of the swordswoman Jirel of Joiry, it's her tales of interplanetary smuggler Northwest Smith that I've long found most appealing. Smith debuted in the November 1933 issue of Weird Tales and, over the course of the next six years, appeared in a dozen more stories in the Unique Magazine and elsewhere. Like adventures of John Carter and other early science fiction, these yarns are now wholly improbable, based as they are on incomplete or just plain erroneous science. They're also a lot of fun, filled with memorable characters and exciting situations.

"The Cold Gray God" opens in the "outlaw city" of Righa at the North Pole of Mars. A mysterious woman, hooded and cloaked in "the concealing folds of rich snow-cat fur," strolls down the down the cobblestoned streets of the city in search of someone. She only stops when she spies

a man as he belted his heavy coat of brown pole-deer hide and stepped briskly out into the street. He was tall, brown as leather, hard-featured under the pole-deer cap pulled low over his eyes. They were startling, those eyes, cold and steady, icily calm. Indefinably he was of Earth. His scarred dark face had a faintly piratical look, and he was wolfishly lean in his spaceman's leather as he walked lightly down the Lakklan, turning up the deer-hide collar about his ears with one hand. The other, his right, was hidden in the pocket of his coat.

This is Northwest Smith, the very person for whom she's looking. She asks him to come with her, but he's reluctant to do so.

"What do you want?" he demanded. His voice was deep and harsh, and the words fairly clicked with a biting brevity.

"Come," she cooed, moving nearer again and slipping one hand inside his arm. "I will tell you that in my own house. It is so cold here."

Smith allowed himself to be pulled along down the Lakklan, too puzzled and surprised to resist. That simple act of hers had amazed him out of all proportion to its simplicity. He was revising his judgment of her as he walked along over the snowdust cobbles at her side. For by that richly throaty voice that throbbed as colorfully as any dove's, and by the subtle swaying of her walk, he had been sure, quite sure, that she came from Venus. No other planet breeds such beauty, no other women are born with the instinct of seduction in their very bones. And he had thought, dimly, that he recognized her voice.

When at last the woman takes Smith to her home, she flings back her cloak "in one slow, graceful motion," revealing her face for the first time. The smuggler's "iron poise" is shaken by what he sees; not only was she a "breath-taking beauty," she is a famous woman.

Judai of Venus had been the toast of three planets a few years past. Her heart-twisting beauty, her voice that throbbed like a dove's, the glowing charm of her had captured the hearts of every audience that heard her song. Even the far outposts of civilization knew her. That colorful, throaty voice had sounded upon Jupiter's moons, and sent the cadences of "Starless Night" ringing over the bare rocks of asteroids and through the darkness of space.

And then she vanished. Men wondered awhile, and there were searches and considerable scandal, but no one saw her again. All that was long past now. No one sang "Starless Night" any more, and it was Earth-born Rose Robertson's voice which rang through the solar system in lilting praise of "The Green Hills of Earth." Judai was years forgotten.

And now she was standing before Northwest Smith in a criminal haven atop the Red Planet. Judai explains that she had come because "something called" to her and she "could not resist it." "I have been searching for a long time … for such a man as you – a man who can be entrusted with a dangerous task." Though suspicious, Smith is nevertheless intrigued and wants to know the nature of this task.

"There is a man in Righa who has something I very much want. He lives on the Lakklan by that drinking-house they call the Spaceman's Rest … The man's names I do not know, but he is of Mars, from the canal-countries, and his face is deeply scarred across both cheeks. He hides what I want in a little ivory box of drylander carving. If you can bring that to me you may name your own reward."

Like any good story of a noir-ish sort, nothing, including Judai of Venus, is what it seems, but, of course Northwest Smith is a man accustomed to such situations. Still, he is ever in need of money and, when Judai agrees to his terms – "Ten thousand gold dollars to my name in the Great Bank of Lakkjourna, confirmed by viziphone when I hand you the box." – he accepts the job. He soon finds himself entangled in a mystery far worse than he could have imagined, involving one of the dark, nameless "gods" that once ruled over Mars millennia before the coming of Earthmen.

"The Cold Gray God" is a quintessential Northwest Smith tale, in which the world-weary interplanetary smuggler finds himself face-to-face with a malevolent cosmic entity when he agrees to help a beautiful woman in trouble. What sets it apart from others with a similar plot are the very personal stakes for Smith. He finds that it's not Judai who is seeking "a man like [him]," but rather the something that called her to Mars. It's a compelling set-up and it contributes greatly to the success of the tale, especially if, like me, you're fond of science fiction from the first half of the last century.

August 20, 2022

We Love Crafts

Lovecraft has an undeserved reputation for having been humorless; nothing could be farther from the truth. Not only do some of his tales contain elements of intentional humor, but his letters are filled with examples of his fondness for puns, jokes, and drollery, to which the reminiscences of his many friends and colleagues can attest. Like all human beings, Lovecraft had many faces and it would do his life a disservice to reduce him to a single dimension – a practice of which we're all sometimes guilty when it comes to our forebears.

Happy birthday, HPL!

https://reparrishcomics.com/post/106253805118

August 19, 2022

Dear Abby

Like the Back of My Hand

In the more than four decades I've been involved in the hobby of roleplaying, I've played a lot of different games – and spent a lot of time exploring the settings associated with those games. I was reminded of this during the past week, because I'm going to be playing in a new Traveller campaign set in the universe of GDW's Third Imperium. As I was generating my character, I very quickly found myself imagining who he is and how he fits into the larger setting of the game. Indeed, it was quite easy for me to view the results of my random rolls through the lens of the setting of the Third Imperium and this, in turn, provided me with additional ideas about my character's history and personality. For example, the fact that he has a low Social Standing score and was repeatedly passed over for commissioning as an officer in the Imperial Navy suggested to me that he might have a grudge against the hidebound aristocracy of the Imperium. Of course, the rolls themselves suggested very little of this; I was simply interpreting them in this way because of my deep knowledge of the Third Imperium setting.

In the more than four decades I've been involved in the hobby of roleplaying, I've played a lot of different games – and spent a lot of time exploring the settings associated with those games. I was reminded of this during the past week, because I'm going to be playing in a new Traveller campaign set in the universe of GDW's Third Imperium. As I was generating my character, I very quickly found myself imagining who he is and how he fits into the larger setting of the game. Indeed, it was quite easy for me to view the results of my random rolls through the lens of the setting of the Third Imperium and this, in turn, provided me with additional ideas about my character's history and personality. For example, the fact that he has a low Social Standing score and was repeatedly passed over for commissioning as an officer in the Imperial Navy suggested to me that he might have a grudge against the hidebound aristocracy of the Imperium. Of course, the rolls themselves suggested very little of this; I was simply interpreting them in this way because of my deep knowledge of the Third Imperium setting.Later, I marveled a bit at this. I do know a great about the Third Imperium, having been a fan of Traveller since 1983. I was also heavily involved in Traveller fandom in the '90s, which eventually led to my writing for Traveller: The New Era and GURPS Traveller. Consequently, it makes a great deal of sense that I should know the setting as well as I do. At the same time, there's a certain sense in which this is profoundly weird. Knowing the minutiae of a wholly imaginary place is a peculiar kind of knowledge. It'd be one thing if I were ramble on at length about the Napoleonic Wars, the suppression of the monasteries under Henry VIII, or the Russian Civil War, but it's wholly another if I do the same about the Interstellar Wars, the Psionic Suppressions, or the Imperial Civil War. I'm not suggesting there's anything wrong with knowing so much about a fictional setting, only that I can't help but find it a little odd.

Of course, Traveller's Third Imperium isn't the only fictional setting about which I know a great deal. I also know a great deal about Tékumel, knowledge gained in no small part due to my refereeing a longstanding campaign in the setting, not to mention producing a well regarded fanzine about it. Just like the Third Imperium, I can talk at length about the intricacies of this imaginary planet, including its history and inhabitants – and do so with a confidence that might suggest, to the uninitiated, that I was talking about a real place rather than a fictitious one. That's a testament to the power of the imagination, to be sure, but, as I said above, it's also more than a little weird.

Am I alone in thinking this? For that matter, does anyone else possess a similarly high degree of knowledge about an imaginary place, particularly one designed for roleplaying games? I assume there must be, for example, Glorantha-philes who know as much about that setting as I do about Tékumel, but what about other RPG settings? I'd be very curious to hear what others have to say on this topic, as it's been on my mind quite a bit lately.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers