James Maliszewski's Blog, page 97

October 7, 2022

"Has Steve Jackson lost his mind?"

What Are Levels For?

In light of my earlier post on levels, I find myself wondering: what are levels for? This is a sincere question on my part. Levels – by which I mean experience levels – are simply one of those things that Dungeons & Dragons has always had but whose purpose I never questioned. Obviously, levels are a marker of accumulated experience and thus advancement, but why does that even matter?

In OD&D, there's an implicit suggestion that experience level is indexed to the difficulty posed by the typical inhabitants of a given dungeon level (hence the re-use of the key term). However, that suggestion is a very loose one, since the Monster Level Tables found in The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures don't present a one-for-one correlation between dungeon level and monster level (which is to say, hit dice – itself an inexact measure of relative difficulty). And, of course, the Wilderness Wandering Monster tables don't even make a pretense of correlating difficulty with monster level/hit dice, so what's going on?

Again, I want to reiterate I'm being sincere in asking about the purpose of levels in D&D. It may very well be that, despite my long years of playing the game, I've simply been too thickheaded to understand their point beyond providing a simple milestone for when a character gains access to more potent abilities. If so, I'd be grateful to anyone who can enlighten me on this matter. Plenty of other RPGs manage to get by without levels; why does D&D have them?

October 6, 2022

Grousing about Levels

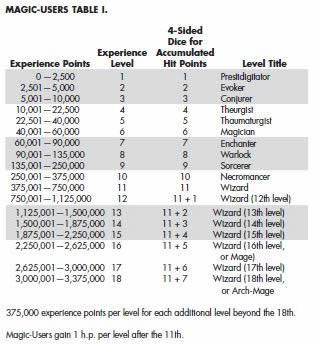

One of the first things you'll notice if you take a look at an experience table for any class in any edition of D&D is that, as level increases, so too do hit points. Glancing at other charts indexed to level reveals that nearly every important mechanical feature of a class, such as its combat effectiveness, saving throws, spell and other abilities, likewise increase in step with level increases.

While it's certainly simpler to tie every ability to a character's level, it doesn't make much sense. Logically – to the extent that word has any meaning in this context – abilities ought to go up separately, as a character makes use of them and thereby becomes better at using them or through study and practice. Of course, this is not how D&D works or was ever intended to work. I don't blame the game for not conforming to this specific understanding of experience.

While it's certainly simpler to tie every ability to a character's level, it doesn't make much sense. Logically – to the extent that word has any meaning in this context – abilities ought to go up separately, as a character makes use of them and thereby becomes better at using them or through study and practice. Of course, this is not how D&D works or was ever intended to work. I don't blame the game for not conforming to this specific understanding of experience.

In my House of Worms campaign, which uses Empire of the Petal Throne, this issue has reared its head several times. Unlike D&D, EPT includes a rudimentary skill system that delineates the areas of knowledge a character knows at the start of his career. In addition, as the character gains levels, he has the opportunity to acquire new skills, in addition to the more usual D&D-ish benefits of more hit points, greater combat effectiveness, etc. But what if a character wants to pick up a new skill outside of a level increase? This is an issue, because level increases in EPT occur much more slowly than in D&D. Furthermore, among the possible skills are things like foreign languages that ought to be learnable simply by seeking out a tutor or by spending enough time in a foreign land among native speakers to develop some degree of fluency. (To be fair, this is also an issue in D&D, which ties language acquisition to Intelligence score.)

In my campaign, I allowed characters to acquire new skills (and spells) by spending time and money to study with someone capable of teaching them. This made logical sense to me, since that's how people acquire new skills in the real world. It was also attractive as part of the game, because it immersed the characters further in the setting. If, for example, they wanted to learn the Livyáni language prior to their visit to that far-off land, they'd need to find and hire an NPC to teach them. If one of them wanted to learn the sphere of impermeable quiescence spell, he'd need to visit the Temple of Sárku and cajole one of its sorcerers into instructing him in its intricacies. All of this led to a greater connection to the people and institutions of the setting, which I consider important to the long-term success of the campaign.

But none of this, strictly speaking, is allowed by the game. More to the point, it's contrary to the way skill acquisition is presented in the Empire of the Petal Throne rulebook, which ties it to level advancement, just like hit points or saving throws. Now, obviously, I'm well within my rights as the referee to change anything in the rulebook I want and have done so without any qualms. However, that doesn't change the fact that what I am doing – detaching a level-based ability from levels – is the camel's nose under the tent for uncoupling experience gain, level advancement, and ability improvement.

I'm by no means opposed to this line of thought. Indeed, I'm rather well disposed toward it, especially of late. At the same time, there's no denying that it inevitably leads to some places I'm not sure Dungeons & Dragons (and games based on its model, like EPT) can go very far. That might explain why I find myself looking longingly at Basic Role-Playing and its descendants for inspiration, even though I am instinctively more inclined toward the D&D approach to most things, given its relative simplicity for newcomers.

I'd be very interested in hearing others' thoughts on this matter, particularly from those who've wrestled with it in their own campaigns.

Dare to Be Stupid

In my post about my ongoing Twilight: 2000 campaign, I mentioned that the players are frequently afflicted with analysis paralysis. By this, I mean that the players sometimes spend sessions doing little more than discussing the pros and cons of the various options available to their characters rather than making a decision and acting on it. I don't mean to sound harsh in pointing this out, particularly since some of these sessions spent discussing options have actually been very enjoyable. They're more like in-character strategizing than what is usually meant by analysis paralysis. At the same time, I can't deny – and I suspect many of the players in the campaign would agree – that not every such session has been so enjoyable. Indeed, far too many have amounted to little more than the characters spinning their wheels, hoping that the "right" path ahead becomes clear.

In my post about my ongoing Twilight: 2000 campaign, I mentioned that the players are frequently afflicted with analysis paralysis. By this, I mean that the players sometimes spend sessions doing little more than discussing the pros and cons of the various options available to their characters rather than making a decision and acting on it. I don't mean to sound harsh in pointing this out, particularly since some of these sessions spent discussing options have actually been very enjoyable. They're more like in-character strategizing than what is usually meant by analysis paralysis. At the same time, I can't deny – and I suspect many of the players in the campaign would agree – that not every such session has been so enjoyable. Indeed, far too many have amounted to little more than the characters spinning their wheels, hoping that the "right" path ahead becomes clear.Caution, of course, is to be commended. At the same time, an abundance of caution is not the gateway to adventure – and adventure is the point of nearly every RPG I've ever played. For that reason, I've come to realize that it's vitally important that every group of players have at least one player willing to be That Guy™ from time to time. You know who I mean: the fighter who rushes headlong into combat with nary a thought to his (or anyone else's) safety; the thief who sneaks ahead to pick the pocket of the High Priest of the Temple of Chaos, the halfling who decides to find out what the lever in the middle of the wall does by pulling it, etc. etc.

Some of my fondest memories from roleplaying campaigns involve players leaping before they looked, whether because they felt it was "what my character would do," an impish sense of fun, or simple boredom. Whatever the reason, recklessness proved vital to shattering the vise grip of caution over many a session. One of the many joys of a roleplaying game is the ability to do things, through your character, that you'd never do in real life. This includes acts of supreme foolhardiness that, even in context, don't always make sense – yet are undeniably enjoyable nonetheless.

Lest it appear that I'm laying the blame for circumspection solely at the feet of players, allow me to demonstrate my own role in encouraging it. In my House of Worms campaign, there's a player character named Kirktá, who's a young and inexperienced priest of Durritlámish. He joined the campaign as a 1st-level character, while most of his companions were 4th or 5th-level at the time. Kirktá is physically weak but very eager and so, from his earliest days in the campaign, would often rush into battle with his trusty staff, even though there was a good chance that even a single blow against him would result in his death. Every time Kirktá's player stated his character intended to do this, I'd always ask, "Are you sure you want to do that?" To his player's credit, he almost always forged ahead, in spite of my warnings.

I intended my questions to act as a reminder to Kirktá's player about the seriousness of what he was planning for his character to do. I'm not the kind of referee who revels in players making bad decisions and suffering the consequences. In general, I prefer to make sure everyone is aware of the possible consequences of what they say they're doing. At least, that's what I think I'm doing. Lately, though, I've come to realize that my regular "Are you sure you want to do that?" might be encouraging the very overabundance of caution that sometimes brings the action to a grinding halt. My Jiminy Cricket act might be having an adverse effect on the campaign by throttling the brash enthusiasm that is the very stuff from which good gaming is made.

It's a sobering thought and one I've been thinking about a lot lately. One of the seminal moments in the history of the House of Worms campaign, one that set into motion so many of the terrific sessions my players and I have had over the last seven and a half years, was when another player did something foolish by desperately casting a spell while wearing metal armor. By all objective standards, that was a stupid thing to do – and thank the Lords of Stability and Change that he did. Looking back on it now, that moment forever altered the trajectory of the House of Worms campaign and made it what it is today, namely, one of the best RPG campaigns in which I have ever participated. Had that player been more cautious, had he looked before he leaped, who knows where we'd be today?

All of which is just a longwinded way of saying that caution is often the antithesis of adventure and adventure is what we're all here for, right?

October 5, 2022

9 Months and 18 Days

Earlier this year, I wrote a brief post about the Twilight: 2000 campaign I began in December of 2021. This campaign is in addition to my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, which is still ongoing. There's some overlap between the players of the two campaigns, but the majority of the Barrett's Raiders players don't participate in House of Worms. I should also note that we make use of the new edition of T2K published by Free League rather than either of the old GDW editions. (One of these days I should write a full review of the new edition, since, after nine months of play, I think I have a decent handle on its strengths and weaknesses,)

Earlier this year, I wrote a brief post about the Twilight: 2000 campaign I began in December of 2021. This campaign is in addition to my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, which is still ongoing. There's some overlap between the players of the two campaigns, but the majority of the Barrett's Raiders players don't participate in House of Worms. I should also note that we make use of the new edition of T2K published by Free League rather than either of the old GDW editions. (One of these days I should write a full review of the new edition, since, after nine months of play, I think I have a decent handle on its strengths and weaknesses,)The title of this post is a reference to the fact that, while the campaign has been up and running for nine months of real time, only a few weeks of game time have passed – an average of about two game days for every month we've been playing. That may seem like an unduly slow pace, but a lot has happened in those few weeks of game time, as the characters have made their way from Kalisz toward the Free City of Kraków. Along the way they've scrounged for supplies, aided Polish civilians in the town of Krzepice, avoided dealing with some rogue US soldiers who'd established a base in Dobrodzień, dodged elements of the Soviet Third Tank Army, and more. It's been a very enjoyable ride for me as the referee and, I assume, the players, since they keep showing up each week.

Twilight: 2000 has always included a very strong hexcrawl element to its gameplay. The characters, after all, are the survivors of a US mechanized infantry division smashed by a Warsaw Pact offensive and now are left to their own devices. Whatever their goals, whether short-term or long-term, they have no choice but to travel overland through the terrain of war-torn Poland. Much of what happens in a given session is the result of random encounters that occur along the way. The Free League edition of the game is very good in this regard, providing lots of useful tables, not to mention maps, from which the referee can cobble together situations with which the characters can deal. Of course, there are also set encounters, too, scattered throughout the countryside, such as the aforementioned Free City of Kraków.

The characters' ostensible plan is to find other NATO forces so that they can get back to (relative) safety and eventually the USA. That's what led them to Kraków in the first place. As a free city independent of all sides in the ongoing war, they figured it'd be a good place to hole up for a while and get a better lay of the land. Unfortunately, Kraków proved almost as fraught with danger as the countryside, albeit of a different sort. The Free City is wracked with factions, several of whom attempted to recruit the characters to their cause. It quickly became clear that the place was a powder keg about to blow and they'd be better off leaving on their own terms while they still could do so.

While in the city, the characters did succeed in making contact with other NATO (and NATO-friendly) personnel. This not only increased their numbers – providing a pool of secondary and replacement characters – but also opened up more options to them, as they plan their next move, From what they have learned, the remaining NATO forces in Poland have retreated to the northwest of the country, where Free (aka non-Communist) Polish forces have established themselves. That's more or less on the other side of the country from their current location, which is why they're currently considering the use of a boat (or several) to move north more quickly.

As I said at the beginning of this post, the campaign has been very enjoyable so far, though not without its challenges. The wide range of possible avenues for character action has sometimes led to analysis paralysis on the part of the players. This, in turn, has sometimes made it difficult for me to anticipate what they might do and keep even five minutes ahead of them, which is what I prefer in campaigns like this. Consequently, I feel as if I've been thrown back on my heels more often than I like. This isn't something that happens often in, say, my House of Worms campaign, where I feel like I have a good handle on things most of the time. With this, I feel much less confident, but that's probably a good thing. I now have to exercise "muscles" I haven't in a while, not to mention re-learn certain refereeing skills I'd apparently let atrophy.

Onward!

October 4, 2022

Retrospective: The Northern Reaches

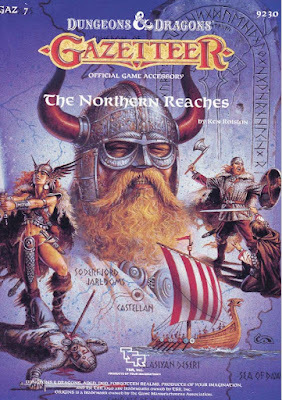

I mentioned, in last week's retrospective on

The Grand Duchy of Karameikos

, that I didn't own many modules in the D&D Gazetteer line, in part because of my disappointment with its inaugural release. Despite this, I did own the seventh in the series, The Northern Reaches, released in 1988 and written by Ken Rolston and Liz Danforth – and, to this day, I consider it one of the most interesting things ever published for the D&D game line.

I mentioned, in last week's retrospective on

The Grand Duchy of Karameikos

, that I didn't own many modules in the D&D Gazetteer line, in part because of my disappointment with its inaugural release. Despite this, I did own the seventh in the series, The Northern Reaches, released in 1988 and written by Ken Rolston and Liz Danforth – and, to this day, I consider it one of the most interesting things ever published for the D&D game line. Like all the other entries in the Gazetteer line, The Northern Reaches is, first and foremost, a detailed examination of one of the regions of the Known World setting (soon to be known as Mystara). In this case, the region in question covers three realms, namely Ostland, Vestland, and the Soderfjord Jarldoms, all of whom share a culture that resembles that of the Norse peoples of medieval Europe. However, The Northern Reaches is more than that. In presenting these three nations, including their histories, societies, and major NPCs, the module also presents several new optional rules for use with D&D and it's these rules that, in my opinion, make the module so fascinating.

Co-author Ken Rolston was already a veteran RPG writer by the time this book appeared (as was Liz Danforth). Among the many games on which he worked was Chaosium's RuneQuest, for which he'd eventually serve as developer during the all-too-brief "RuneQuest renaissance" of the early 1990s. I mention this because, in my opinion, Rolston brings to bear many of the skills he no doubt learned working on the mythical world of Glorantha. The Northern Reaches is a remarkable product that takes inspiration from a real world historical culture to present a fantastical version of the same, without forgetting that this is a module for Dungeons & Dragons and should, therefore, be both accessible and fun.

By and large, Rolston and Danforth succeed admirably in this. One of the ways they do so is through the use of four different NPCs whose viewpoints on various matters of interest can be found throughout the 32-page Players Book, which, along with the 64-page DM Book, makes up the product. These NPCs – three humans and dwarf – all have unique voices and areas of expertise. Consequently, when they describe aspects of the Northern Reaches, they do so with varying degrees of bias. While this means not everything they say is wholly reliable, it also gives players and DM alike a sense of how the people in this region view the world. It's also a terrific guide for playing Northmen either as player or non-player characters.

The DM Book, though larger, is the least interesting of the two. This book is written in a matter-of-fact way, presenting the history, geography, society, and current events of each of the three realms, with emphasis placed on those that are most useful for adventuring in them. We also learn about the unique nature of certain nonhuman races here, such as the dwarves and trolls, which are based a bit more on their Norse mythological equivalents (though not too much, lest this run counter to the expectations of standard D&D). There are also extensive treatments of the major personalities of the three realms, in addition to multiple adventure ideas and campaign outlines. Interestingly, there are also brief guidelines for converting the module to AD&D and even making use of the material in campaigns set in either Greyhawk or the Forgotten Realms.

The Players Book presents the three realms of Ostland, Vestland, and the Soderfjord Jarldoms as potential homelands for player characters. To that end, there is a section devoted to generating Northmen, starting with an optional personality traits system that's more or less identical to the one in Pendragon, albeit with slightly different sets of opposing traits (no "Chaste/Lustful," for example – this is a family-friendly game product!). There are also optional systems for determining a character's reputation, background, family status, past experiences, skills, and more. None of these systems is mechanically complex, but they're all sufficiently flavorful that I think they'd go some way toward marking a character from the Northern Reaches as distinctive.

There's also a section on the godar, as clerics are known in this region of the Known World. These Norse priests have different abilities and obligations based on the deity – I mean, immortal – they serve. These immortals should be familiar to anyone with knowledge of our world's Norse mythology. Odin, Thor, and Loki are all here, along with several others. Runes and rune magic also get their own treatments here. Again, the new systems associated with these things are fairly simple and don't deviate much from standard D&D, but they do so just enough that the end result is something flavorful and fun.

I'd be exaggerating if I called The North Reaches revolutionary or even groundbreaking. In many ways, it's a fairly ordinary transposition of the historical Norse to a fantasy setting, with almost no changes to differentiate them from their inspirations. Yet, in the context of late 1980s Dungeons & Dragons, that's more than enough to mark it as worthy of praise. That Rolston and Danforth do so in a way that simultaneously conveys the spirit of its inspirations while never losing sight of its purpose as a D&D supplement sets it apart from many similar products in the history of the hobby. That's probably why, even after all these years, I still retain a great fondness for The Northern Reaches and wish I'd paid more attention to the Gazetteer series at the time.

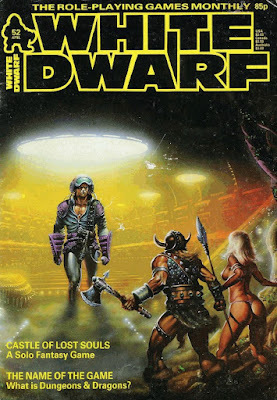

White Dwarf: Issue #52

Alan Craddock's depiction of a meeting between science fiction and fantasy characters graces the cover of issue #52 of White Dwarf (April 1984). As I've commented before, this is a common theme for WD covers and a subject near and dear to my heart. Meanwhile, Ian Livingstone's editorial is addressed to "new and old readers alike." In it, he hopes that "our faithful followers" will not object to the inclusion of content aimed at newcomers to the hobby. I imagine the inclusion of such content reflects the fact that, by this time, White Dwarf had become available at newsstands and thus might have attracted the attention of those otherwise unfamiliar with RPGs.

Alan Craddock's depiction of a meeting between science fiction and fantasy characters graces the cover of issue #52 of White Dwarf (April 1984). As I've commented before, this is a common theme for WD covers and a subject near and dear to my heart. Meanwhile, Ian Livingstone's editorial is addressed to "new and old readers alike." In it, he hopes that "our faithful followers" will not object to the inclusion of content aimed at newcomers to the hobby. I imagine the inclusion of such content reflects the fact that, by this time, White Dwarf had become available at newsstands and thus might have attracted the attention of those otherwise unfamiliar with RPGs.

This is one of those times when I wish we had better information on the growth in popularity in sales for roleplaying games. I tend to think of 1984 as just beyond the peak of the hobby's faddishness; from that point on, there is inevitable decline. That's based on very little but my own limited experiences and might well not be true everywhere. Indeed, I think there's good evidence that, in the UK, growth was still happening at this time, as the still-rising fortunes of Games Workshop would attest. In any case, it's a topic that continues to interest me and I live in hope we'll one day have more reliable data on the first decade of the hobby.

"The Name of the Game" by Marcus L. Rowland is an example of the kind of content geared for newcomers that Livingstone mentions in his editorial. It's a two-page overview both of roleplaying in general and Dungeons & Dragons in particular. It's fine for what it is, though, as I always ask when confronted with articles like this, who is this for? I have a very hard time imagining that a newcomer would buy a copy of White Dwarf without already knowing what a roleplaying game is. In that case, what's the purpose of articles like this? It's short, so it doesn't waste too much of this issue's precious pages, but, even so, I fail to see the value in it.

"Out of the Blue" by Daniel Collerton is a nice article that aims give clerics spell lists more in tune with the deities they serve. I'm quite sympathetic to Collerton's general point of view, so I'm naturally inclined to like this. At the same time, the article is simple and straightforward, making use of a combination of revised spell lists and a few new spells to give each cleric a distinct flavor based on his religion. In many ways, it anticipates the ideas developed in later TSR books like Dragonlance Adventures or in Second Edition AD&D, but without the need for spheres/domains.

"Open Box" reviews several new products, starting with Talisman, which – surprisingly – receives a score of only 6 out of 10. The reviewer found that the game tended to drag on, which is a fair criticism, I think. Also reviewed was another Games Workshop game, Battlecars, which was scored more favorably (8 out of 10). Not so lucky is Dragonriders of Pern by Mayfair. The reviewer points out its "rotten artwork, unclear rules, complex and unwieldy game mechanics, [and] high price," giving it 4 out of 10. Finally, there's the series of Lost Worlds fantasy combat books. The reviewer likes them in general, but nevertheless finds of "limited appeal," hence the mediocre score of 6 out of 10.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" quickly reviews many books, including Isaac Asimov's Foundation's Edge (which he doesn't care for), Piers Anthony's Dragon on a Pedestal (which he does, in spite of himself), Fred Saberhagen's Empire of the East (thumbs up), Vonda McIntyre's Superluminal (thumbs down), along with Robertson Davies's High Spirits (the best collection of ghost stories since M.R. James). Langford is something of an acquired taste and I frequently struggle reading his columns decades after they were written. Still, there's a strange joy in remembering that, once upon a time, our little hobby still looked to literature rather than itself and its distaff offspring for inspiration. I miss those days.

"Close Encounters of the First Kind" presents four new monsters for use with D&D, including one, the spider dragon, by editor Ian Livingstone himself. "Microview" by Russell Clarke reviews two computer games, Usurper (5 out of 10) and Caribbean Trader (8 out of 10). He also presents a short program to aid in handling impulse movement in Starfleet Battles. "To Live Forever" by Andy Slack looks at immortality in Traveller. Slack focuses on achieving this through drugs, medicine, clones, and low berths, not to mention the adverse effects of each approach. He ends the article with a sample scenario that introduces some of these concepts into a campaign.

"The Castle of Lost Souls" by Dave Morris and Yve Newnham is the first part of an extended solitaire adventure built on a model similar to the Fighting Fantasy books that were all the rage at the time. I remember really enjoying this series at the time. It's quite well done for what it is – no surprise, really, given that Morris would later go on to write the Fabled Lands series of gamebooks. "The Serpent's Venom" by Liz Fletcher is a beginning AD&D scenario that's quite cleverly done. Fletcher subverts a common trope of low-level adventures – a quest given by a mysterious NPC – to present something that looks like a lot of fun to play.

Dave Morris returns with "Rings," a collection of more than a dozen magical rings for use with RuneQuest. "Pandora's Box," on the other hand, is a collection of six miscellaneous magical items by various authors for D&D, including the casket of troubles. Joe Dever and Gary Chalk (later of Lone Wolf fame) offer "A Hard Day's Knight," a "close-up look at fighter figures," complete with color photographs. I used to love articles like this, since I was absolutely awful at painting and never ceased to marvel at others' artistry. This issue also includes new installments of "Gobbledigook," "The Travellers," and "Thrud the Barbarian." The latter is the first part of "The Three Tasks of Thrud," a short series of connected installments that tell a longer story of the necromancer To-Me Ku-Pa's enlistment of the dimwitted barbarian to undertake the titular tasks of the title.

Issue #52 is a bit less enjoyable than its immediate predecessor but still solid. White Dwarf continues to distinguish itself for the variety of its content, as well as the slightly off-kilter approaches it took to its content. Compared to Dragon, it's a bit less professional and predictable, which is both a blessing and curse. For myself, White Dwarf gave me new perspectives on the hobby that I wouldn't otherwise have had. For that, I remain grateful, whatever criticisms I might have of individual issues.

October 3, 2022

Live or Die: The Choice is Yours

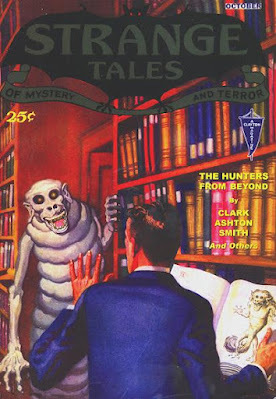

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Hunters from Beyond

In addition to his more extensive (and well-known) story cycles, such as those of Hyperborea, Averoigne, and Zothique, Clark Ashton Smith also wrote several loosely connected stories with recurring characters or concepts. A prominent example of this is the character of Philip Hastane, who first appeared in his celebrated "The City of the Singing Flame." Hastane would seem to be a fictional analog of Smith himself, since he is not only a poet and writer of weird fiction but also lives in a log cabin near Auburn, California, as did the real CAS.

In addition to his more extensive (and well-known) story cycles, such as those of Hyperborea, Averoigne, and Zothique, Clark Ashton Smith also wrote several loosely connected stories with recurring characters or concepts. A prominent example of this is the character of Philip Hastane, who first appeared in his celebrated "The City of the Singing Flame." Hastane would seem to be a fictional analog of Smith himself, since he is not only a poet and writer of weird fiction but also lives in a log cabin near Auburn, California, as did the real CAS. Hastane's second appearance was in "The Hunters from Beyond," published in the October 1932 issue of Strange Tales. Strange Tales was a would-be competitor to Weird Tales that produced only seven issues between 1931 and 1933. During its brief run, the magazine nevertheless attracted several high-profile pulp writers to its pages, such as Smith, Robert E, Howard, and Jack Williamson, perhaps due to its higher rate of pay (2 cents per word compared to WT's one cent). This seems to have been precisely why Smith submitted "The Hunters from Beyond" to Strange Tales. Like most writers for the pulps, he was always on the lookout for more lucrative markets for prodigious output of weird fiction.The story begins quickly. Hastane is making one of his biannual visits to San Francisco to call upon his "second or third cousin," the sculptor Cyprian Sincaul. While in the city, he drops by Toleman's bookstore and begins to rummage "among the curiously laden shelves." He comes across a "deluxe edition" of Francisco Goya's Proverbes and is "soon engrossed in the diabolic art of these nightmare-nurtured drawings." His reading is interrupted by a terrible sight, as "if some hellish conception of Goya had suddenly come to life and emerged from one of the pictures in the folio."

What I saw was a forward-slouching, vermin-gray figure, wholly devoid of hair or down or bristles, but marked with faint, etiolated rings like those of a serpent that has lived in darkness. It possessed the head and brow of an anthropoid ape, a semi-canine mouth and jaw, and arms ending in twisted hands whose black hyena talons nearly scraped the floor. The thing was infinitely bestial, and, at the same time, macabre; for its parchment skin was shriveled, corpselike, mummified, in a manner impossible to convey; and from eye sockets well-nigh deep as those of a skull, there glimmered evil slits of yellowish phosphorescence, like burning sulphur. Fangs that were stained as if with poison or gangrene, issued from the slavering, half-open mouth; and the whole attitude of the creature was that of some maleficent monster in readiness to spring.

Though I had been for years a professional writer of stories that often dealt with occult phenomena, with the weird and the spectral, I was not at this time possessed of any clear and settled belief regarding such phenomena. I had never before seen anything that I could identify as a phantom, nor even an hallucination; and I should hardly have said offhand that a bookstore on a busy street, in full summer daylight, was the likeliest of places in which to see one. But the thing before me was assuredly nothing that could ever exist among the permissible forms of a sane world. It was too horrific, too atrocious, to be anything but a creation of unreality.

Even as I stared across the Goya, sick with a half-incredulous fear, the apparition moved toward me. I say that it moved, but its change of position was so instantaneous, so utterly without effort or visible transition, that the verb is hopelessly inadequate. The foul specter had seemed five or six feet away. But now it was stooping directly above the volume that I still held in my hands, with its loathsomely lambent eyes peering upward at my face, and a gray-green slime drooling from its mouth on the broad pages. At the same time I breathed an insupportable fetor, like a mingling of rancid serpent-stench with the moldiness of antique charnels and the fearsome reek of newly decaying carrion.

In a frozen timelessness that was perhaps no more than a second or two, my heart appeared to suspend its beating, while I beheld the ghastly face. Gasping, I let the Goya drop with a resonant bang on the floor, and even as it fell, I saw that the vision had vanished.

Unsettled, Hastane leaves Toleman's in haste and makes his way to Sincaul's studio on the second floor of a nearby building. He finds the sculptor "wiping his hands on an old cloth" near "an ambitious but unfinished group of figures" covered in burlap. Nearby were other completed sculptures and a heavy Chinese screen.

At a single glance I realized that a great change had occurred, both in Cyprian Sincaul and his work. I remembered him as an amiable, somewhat flabby-looking youth, always dapperly dressed, with no trace of the dreamer or visionary. It was hard to recognize him now, for he had become lean, harsh, vehement. with an air of pride and penetration that was almost Luciferian. His unkempt mane of hair was already shot with white, and his eyes were electrically brilliant with a strange knowledge, and yet somehow were vaguely furtive, as if there dwelt behind them a morbid and macabre fear.

The change in his sculpture was no less striking. The respectable tameness and polished mediocrity were gone, and in their place, incredibly. was something little short of genius. More unbelievable still, in view of the laboriously ordinary grotesques of his earlier phase, was the trend that his art had now taken. All around me were frenetic, murderous demons, satyrs mad with nympholepsy, ghouls that seemed to sniff the odors of the charnel, lamias voluptuously coiled about their victims, and less namable things that belonged to the outland realms of evil myth and malign superstition.

Sin, horror, blasphemy, diablerie — the lust and malice of pandemonium — all had been caught with impeccable art; The potent nightmarishness of these creations was not calculated to reassure my trembling nerves; and all at once I felt an imperative desire to escape from the studio, to flee from the baleful throng of frozen cacodemons and chiseled chimeras.

Sincaul notices Hastane's reaction to his work and and reacts with pride. Indeed, he boasts that he's "gone pretty far … Further even than you think, probably. If you could know. what I know, could see what I have seen, you might make something really worth-while out of your weird fiction, Philip. You are very clever and imaginative, of course. But you've never had any experience." This startles Hastane, who asks him what he means by this. Sincaul explains that, in the past, he'd tried to depict the supernatural without any firsthand knowledge of it, just as Hastane did in his stories, and the results were always mediocre. "But I've learned a thing or two since then."

Especially in light of his recent experience at Toleman's, Hastane is keen to know more. Sincaul, though, is evasive initially. "I know what I know. Never mind how or why. The world in which we live isn't the only world; and some of the others lie closer at hand than you think. The boundaries of the seen and the unseen are sometimes interchangeable." This statement emboldens Hastane, against his better judgment to describe what happened to him at the bookstore. Sincaul listens before lifting the burlap from the figures on which he'd been working just prior to Hastane's arrival.

Before me, in a monstrous semicircle, were seven creatures who might all have been modeled from the gargoyle that had confronted me across the folio of Goya drawings. Even in several that were still amorphous or incomplete, Cyprian had conveyed with a damnable art the peculiar mingling of primal bestiality and mortuary putrescence that had signalized the phantom. The seven monsters had closed in on a cowering, naked girl, and were all clutching foully toward her with their hyena claws. The stark, frantic, insane terror on the face of the girl, and the slavering hunger of her assailants, were alike unbearable. The group was a masterpiece, in its consummate power of technique — but a masterpiece that inspired loathing rather than admiration. And following my recent experience, the sight of it affected me with indescribable alarm. It seemed to me that I had gone astray from the normal, familiar world into a land of detestable mystery, of prodigious and unnatural menace.

Held by an abhorrent fascination, it was hard for me to wrench my eyes away from the figure-piece. At last I turned from it to Cyprian himself. He was regarding me with a cryptic air, beneath which I suspected a covert gloating.

"How do you like my little pets?" he inquired. "I am going to call the composition 'The Hunters from Beyond'."

The reader can be forgiven for seeing a certain similarity between this story and H.P. Lovecraft's 1927 tale, "Pickman's Model." Such comparisons were made even at the time of the story's initial publication and for good reason: Smith acknowledged to August Derleth that HPL's yarn had served as one of his own inspirations. Ultimately, though, the two stories are quite different. Smith is much more interested in the creation of art and lengths to which artists will sometimes go in order to achieve something greater than they have ever achieved before. It's not a perfect story by any means, but it is a delightfully pulpy meditation on obsession and the madness it can engender – exactly the kind of thing at which Clark Ashton Smith has always excelled.

October 1, 2022

Memorial

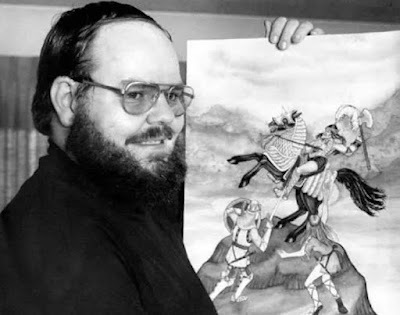

I spent a long time yesterday and today trying to think of the best way to commemorate what would have been Dave Arneson's 75th birthday. In the years since his death in 2009, I think it's fair to say that there's a much greater appreciation for the man and his contributions to both Dungeons & Dragons and the larger hobby of roleplaying that it inspired. At the same time, Arneson remains a much more elusive, even mysterious, a figure than, say, Gary Gygax, with whose name he will forever be linked. There are many reasons why this is the case, not least of which being that Arneson seems to have preferred a certain degree of invisibility, if not necessarily anonymity. He didn't seem to have been an attention seeker and so his role in the history of the hobby tends only to be celebrated on occasions such as this.

I spent a long time yesterday and today trying to think of the best way to commemorate what would have been Dave Arneson's 75th birthday. In the years since his death in 2009, I think it's fair to say that there's a much greater appreciation for the man and his contributions to both Dungeons & Dragons and the larger hobby of roleplaying that it inspired. At the same time, Arneson remains a much more elusive, even mysterious, a figure than, say, Gary Gygax, with whose name he will forever be linked. There are many reasons why this is the case, not least of which being that Arneson seems to have preferred a certain degree of invisibility, if not necessarily anonymity. He didn't seem to have been an attention seeker and so his role in the history of the hobby tends only to be celebrated on occasions such as this.I'm as guilty of this as anyone, as evidenced by the fact that I struggled with finding something interesting or relevant to say in this post. In the end, I decided that the most important thing was simply to remember him and acknowledge that, whatever else he was, Dave Arneson was a man of singular imagination and creativity who hit upon a remarkable, indeed groundbreaking, idea that literally changed the world. I am constantly struck by how many of the concepts and terms of D&D have spread into the wider world, often used by people who've never played in a RPG. That's a level of influence of which few creators can boast and, while he's not solely responsible for that, he was the man who got the ball rolling with his Blackmoor campaign in the spring of 1971.

All of us who enjoy roleplaying games of any sort owe Dave Arneson a huge debt. Happy birthday, Dave. May you be long remembered!

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers