James Maliszewski's Blog, page 96

October 13, 2022

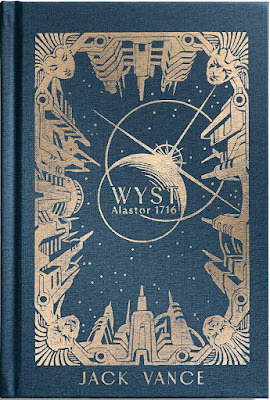

Wyst: Alastor 1716

Though Jack Vance is probably best known among fans of roleplaying games for his works of fantasy, such as his The Dying Earth and its sequels, his works of science fiction are every bit as remarkable, filled with the same memorable characters, imaginative locales, and wild reversals of fortune that are the hallmarks of his long career as a writer.

Though Jack Vance is probably best known among fans of roleplaying games for his works of fantasy, such as his The Dying Earth and its sequels, his works of science fiction are every bit as remarkable, filled with the same memorable characters, imaginative locales, and wild reversals of fortune that are the hallmarks of his long career as a writer. During the 1970s, Vance wrote three science fiction novels set in an area of human-colonized space known as the Alastor Cluster. The third of these, Wyst: Alastor 1716, follows the travels of a restless young man who enters and wins an art contest, the prize for which gives him a round-trip ticket to any world in the Cluster he chooses, along with some spending money. The young man chooses Wyst, whose society is governed by the philosophy of "egalism" that decrees that every person is equal to every other – with somewhat predictable results. Like so many of Vance's works, Wyst is thus equal parts adventure story and satire.

I mention this all because Sword Fish Islands, the company behind the excellent Hot Springs Island, has published an illustrated, fine press version of Wyst: Alastor 1716 in cooperation with Spatterlight Press, which preserves and promotes Jack Vance's literary legacy. Sword Fish Islands very kindly asked me to write the afterword to this edition, which touches on, among other things, the role Vance's stories played in inspiring many of the earliest creators of roleplaying games, particularly Gary Gygax.

If you're a fan of well made, limited editions of classic literature, you might find this lovely new edition of Wyst to your liking.

Oink! Oink!

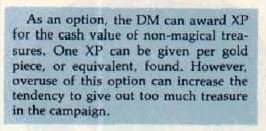

When people ask me what I mean when I say that AD&D Second Edition was not well served by its art, I think of illustrations like this one, which appears in the 2e Dungeon Master's Guide.

Doing It Wrong

I've been re-reading the AD&D Second Edition Dungeon Master's Guide, as part of my continuing exploration of the concepts of experience and level. I thought it might be worthwhile to take a look at how the various TSR editions of the game handle these matters. In doing so, I was surprised to see this bit of highlighted text:

As an option? What's going on here? Prior to looking at this section for the first time in untold years, I had assumed that, when it came to the awarding of experience points, 2e followed closely in the footsteps of its predecessor, with XP being given for the defeat of foes and the acquisition of treasure. That's certainly how I remember XP awards working in Second Edition. It's also how I remember playing the game back in the late '80s and early '90s. Was I playing the game wrong all those years ago?

As an option? What's going on here? Prior to looking at this section for the first time in untold years, I had assumed that, when it came to the awarding of experience points, 2e followed closely in the footsteps of its predecessor, with XP being given for the defeat of foes and the acquisition of treasure. That's certainly how I remember XP awards working in Second Edition. It's also how I remember playing the game back in the late '80s and early '90s. Was I playing the game wrong all those years ago?Yes, apparently. If you play AD&D 2e by the book, there are only two ways that characters earn experience points. The first are the group awards, earned for "victory over their foes." This type of award has existed in every edition of Dungeons & Dragons since 1974 and is based on the hit dice and special abilities of the enemies defeated. The second are individual awards, given out on the basis of a character's class. Thus, a fighter gets an individual award of 10 XP per hit die of a defeated enemy per level, while a magic-user gets one by using spells "to overcome foes or problems" at a rate of 50 XP per level of the spell cast, among other awards. This second type of award is new to Second Edition.

When you look at the individual class awards, you'll notice something interesting. A class award for thieves is 2 XP per gold piece value of treasure obtained. What used to be a default means of obtaining experience – a "group award" in Second Edition's parlance – is now exclusive to thieves (and other rogues) and at twice the previous rate. I can see the train of logic that led to this element of the new edition's design: if you're committed to the idea of individual class-based awards, it makes sense that thieves ought to be rewarded for, well, stealing. However, the rules develop this notion in a way that completely excludes other classes for benefiting, experience-wise, from the acquisition of treasure.

This is a huge shift away from the design of all prior editions of Dungeons & Dragons, which accepted the implicit pulp fantasy assumption that, to one degree or another, all characters are thieves, in the sense that they all benefit from treasure hunting, tomb robbing, and similar larcenous activities. Second Edition is a tacit repudiation of that conception of D&D, which I suppose only makes sense for a post-Dragonlance edition. The shift toward a more "heroic" presentation of the game was well under way by this point and perhaps this change is yet more evidence of it.

How I somehow managed not to take notice of it, though, is a genuine mystery.

October 11, 2022

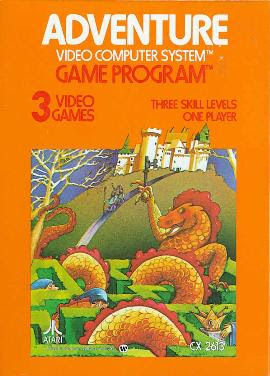

Retrospective: Adventure

Like a lot of kids who grew up in the 1970s and '80s, I was simultaneously obsessed with and frustrated by the emerging technology of videogames – obsessed because, even in those benighted days, their potential was obvious; frustrated precisely because they were still a very long way from fulfilling that potential. Nevertheless, many of the videogames of my youth were truly amazing things, primitive though they must look to 21st century eyes. The best of them were paradigms of one's reach exceeding one's grasp, since technical limitations often prevented even the most talented designers from truly achieving what they set out to do.

Like a lot of kids who grew up in the 1970s and '80s, I was simultaneously obsessed with and frustrated by the emerging technology of videogames – obsessed because, even in those benighted days, their potential was obvious; frustrated precisely because they were still a very long way from fulfilling that potential. Nevertheless, many of the videogames of my youth were truly amazing things, primitive though they must look to 21st century eyes. The best of them were paradigms of one's reach exceeding one's grasp, since technical limitations often prevented even the most talented designers from truly achieving what they set out to do. Neophilia is nevertheless a powerful thing. My friends and I enjoyed playing whatever video or computer games we could get our hands on, especially those with fantasy or science fiction themes. One of the earliest of the former that I remember playing was Adventure, released in 1980 for the Atari Video Computer System (rebranded as the Atari 2600 in 1982). The brainchild of Warren Robinett, who'd previously designed Slot Racers for Atari, Adventure is generally considered the world's first graphical fantasy game and it's precisely for that reason that I so loved it in my youth.

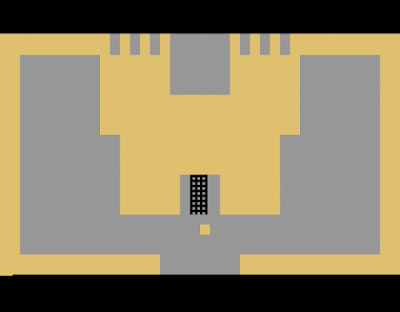

Behold! The ChaliceThe premise of the game is quite simple: an unnamed Evil Magician has stolen the Enchanted Chalice and hidden it somewhere in the Kingdom. The player, whose "character" is represented by a square, must find the Chalice and return it to the Golden Castle where it belongs. Naturally, this is not as easy as it sounds. The Magician has created three dragons to hinder the player in his quest. These are Yorgle the Yellow Dragon, Grundle the Green Dragon, and Rhindle the Red Dragon. At higher levels of difficulty – there are three levels in all – there is also a Black Bat that carries objects throughout the Kingdom. This makes the player's quest more difficult, because the Bat not only moves important items around, it can also swap an item it's carrying with one you're carrying. This is especially annoying when you're carrying something like the Sword that's needed to slay the dragons – or even the Enchanted Chalice, as you're hurrying toward the Golden Castle to win the game.

Behold! The ChaliceThe premise of the game is quite simple: an unnamed Evil Magician has stolen the Enchanted Chalice and hidden it somewhere in the Kingdom. The player, whose "character" is represented by a square, must find the Chalice and return it to the Golden Castle where it belongs. Naturally, this is not as easy as it sounds. The Magician has created three dragons to hinder the player in his quest. These are Yorgle the Yellow Dragon, Grundle the Green Dragon, and Rhindle the Red Dragon. At higher levels of difficulty – there are three levels in all – there is also a Black Bat that carries objects throughout the Kingdom. This makes the player's quest more difficult, because the Bat not only moves important items around, it can also swap an item it's carrying with one you're carrying. This is especially annoying when you're carrying something like the Sword that's needed to slay the dragons – or even the Enchanted Chalice, as you're hurrying toward the Golden Castle to win the game.

Beware! RhindleObjectively, Adventure is not a particularly complex game or, at its lowest level of difficulty, a very hard one. Like many early videogames, much of its apparent difficulty comes from the limitations of the software and hardware of those bygone days. However, difficulty levels 2 and 3 genuinely up the ante, by introducing a number of random elements, mostly involving the placement of important items, that change gameplay in significant ways. They also include some features, like invisible mazes, that I absolutely dreaded as a child, because they were pretty much a death trap if a dragon were pursuing you. At the higher levels of difficulty, Adventure was thus more of a challenge.

Beware! RhindleObjectively, Adventure is not a particularly complex game or, at its lowest level of difficulty, a very hard one. Like many early videogames, much of its apparent difficulty comes from the limitations of the software and hardware of those bygone days. However, difficulty levels 2 and 3 genuinely up the ante, by introducing a number of random elements, mostly involving the placement of important items, that change gameplay in significant ways. They also include some features, like invisible mazes, that I absolutely dreaded as a child, because they were pretty much a death trap if a dragon were pursuing you. At the higher levels of difficulty, Adventure was thus more of a challenge.Of course, it was precisely the challenging nature of the higher difficulty levels that made one feel as if one had accomplished something by succeeding in bringing the Enchanted Chalice back to the Golden Castle. That this often took many, many attempts only reinforced in our imaginations the immensity of what he'd done. That it all took place against the pixelated backdrop of a fantasy setting added further to its appeal. Outside of playing Dungeons & Dragons, which we'd only just discovered in the months prior to Adventure's release, there was no other game like it available at the time. In 1980, simply being the first was enough to hold our attention.

Ultimately, that connection to D&D, however tenuous, is probably what elevates Adventure to the lofty heights of the games most influential over my imagination. Like D&D itself, Adventure was released at just the right time in my own life, when I was at the start of my lifelong love affair with fantasy adventure games and when I'd not yet become a fault-finding snob who hates everything. Back then, I could still find wonder and excitement and even a little fear in a game where your in-game avatar is nothing more than a colored square and fearsome dragons look like ducks. I miss those days sometimes ...

The glory of the Golden Castle!

The glory of the Golden Castle!

The Stafford House Campaign

Four years ago today, Greg Stafford, creator of Glorantha and one of the founders of Chaosium, passed into the eternity of the Gods World. In celebration of his memory, Chaosium has released the first volume of a new series called the Chaosium Archival Collection. This volume,

The Stafford House Campaign

, is a collection of essays Stafford wrote about his then-ongoing RuneQuest campaign during the period between 1978 and 1981, some of which originally saw print in Amateur Press Associations, like The Wild Hunt.

Four years ago today, Greg Stafford, creator of Glorantha and one of the founders of Chaosium, passed into the eternity of the Gods World. In celebration of his memory, Chaosium has released the first volume of a new series called the Chaosium Archival Collection. This volume,

The Stafford House Campaign

, is a collection of essays Stafford wrote about his then-ongoing RuneQuest campaign during the period between 1978 and 1981, some of which originally saw print in Amateur Press Associations, like The Wild Hunt. I don't yet own a copy myself, so I can't speak of its complete contents. However, there's a lengthy excerpt available for free download on the Chaosium website. If that catches your fancy, you can buy the full 84-page version, in either a PDF or POD form. Based solely on the download, it looks like the whole collection will be worth it for anyone interested either in the development of Glorantha or in the early history of the hobby of roleplaying.

October 10, 2022

White Dwarf: Issue #53

Issue #53 of White Dwarf (May 1984) boasts a cover by Angus Fieldhouse depicting wgar appear to be orcs in the service of Saruman from The Lord of the Rings – notice the sigil of the white hand on their shields and battle standard. If so, it's an odd choice, since the issue contains a scenario for use with Warhammer based on the Battle of Pelennor Fields in which Saruman's forces did not participate, having already been defeated at Helm's Deep a couple of weeks prior. Even so, I like the illustration quite a bit; it nicely encapsulates many of the features I strongly associate with the Games Workshop "house style" for artwork.

Issue #53 of White Dwarf (May 1984) boasts a cover by Angus Fieldhouse depicting wgar appear to be orcs in the service of Saruman from The Lord of the Rings – notice the sigil of the white hand on their shields and battle standard. If so, it's an odd choice, since the issue contains a scenario for use with Warhammer based on the Battle of Pelennor Fields in which Saruman's forces did not participate, having already been defeated at Helm's Deep a couple of weeks prior. Even so, I like the illustration quite a bit; it nicely encapsulates many of the features I strongly associate with the Games Workshop "house style" for artwork.Editor Ian Livingstone touches again on the issue of the roleplaying hobby's continued growth. He opines that gamers "who have been in the hobby for many years" might be "a little peeved" that "thousands of newcomers who view the hobby less seriously" than they have intruded their "exclusive" domain. It's an age-old aspect of the hobby, one I've experienced from both sides. If nothing else, this simply proves that there really is nothing new under the sun. Livingstone states that White Dwarf will continue to assist newcomers "by publishing introductory articles and scenarios," but that it would not do so "at the expense of its main editorial features." Whatever one thinks of this approach, I think it's instructive to consider that Games Workshop still exists today, while most of the other mainstays of the hobby, most notably TSR, no longer do so.

Part 2 of Marcus Rowland's introduction to RPGs, "The Name of the Game," appears in this issue. This time, he focuses on games other than Dungeons & Dragons, starting with RuneQuest, which receives the bulk of the article's coverage. Rowland's comments on RQ are interesting. He emphasizes its detailed setting of Gloratha, its unique magic systems, its religions and cults, and, above all, its combat system, which he calls "the main reason for the game's success." He also includes brief discussions of several other RPGs: Tunnels & Trolls, Chivalry & Sorcery, Warhammer, and Man, Myth & Magic – quite an odd assortment to me, but perhaps this reflects the idiosyncrasies of the UK market in the mid-1980s. "Minas Tirith" by Joe Dever is a huge article that presents the Battle of Pelennor Fields from The Return of the King as the basis for a Warhammer fantasy battle scenario. The scenario is designed for two sides, the forces of Gondor and its allies and the forces of the Witch-King of Angmar. Of course, each side has enough units and sub-factions, not to mention named characters, that it would be quite easy to divvy them up into several players. The article includes not only stats for all the forces but suggestions of miniature figures appropriate to represent them. Though I've never been much of a miniature wargames player, I found the article weirdly inspirational and wished I could somehow get the opportunity to play it.

"Open Box" starts its reviews by looking at Games Workshop's Caverns of the Dead, an ostensibly system-neutral (yet obviously intended for D&D) boxed scenario that includes lots of maps and even a referee's screen. The reviewer rates it 7 out of 10 and notes that it's not quite as good a value for the money as a typical D&D module. Two more Fighting Fantasy books, Deathtrap Dungeon and Island of the Lizard King are reviewed, each earning 8 out of 10. I have a personal affection for Deathtrap Dungeon, due to its difficulty, which greatly appealed to me at the time. Finally, there's a review of Scouts for Traveller (7 out of 10).

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" comments upon another of Anne McCaffrey's Pern novels, Isaac Asimov's The Robots of Dawn, and Diana Wynne Jones's The Homeworld Bounders, among a few others. Meanwhile, "The Moonbane" is a piece of original fiction, "a short tale of gothic horror" by Chris Elliot and Richard Edwards. Much more interesting – to me anyway – are the latest installments of the comics "Gobbledigook," "The Travellers," and "Thrud the Barbarian." Also more interesting is Lewis Pulsipher's "Sign Here Please ...," a brief rumination on making pacts with devils in the context of fantasy roleplaying games.

"The Naked Orc" by Rufus Wedderburn is "a study of orcish society." In some ways, it's a bit like Dragon's "Ecology of ..." series, except that it's focused on the politics and sociology of orcs rather than their biology. It's fine, I suppose, though there's nothing particularly clever or revelatory about it. "Spare Parts" is a Car Wars article written by none other than the game's creator, Steve Jackson himself (apparently written on his British namesake's typewriter while on a visit to England). It's mostly a puff piece in which Jackson talks about his plans for game, including a computer version from Origin (which did indeed come out in 1985).

Part 2 of Dave Morris and Yve Newnham's "The Castle of Lost Souls" solo adventure appears here, continuing the scenario begun in the previous issue. "Three of a Kind" by Michael Clarke presents three NPCs for use with Traveller; they can be used either as patrons or antagonists. "Of Oak, Ash, and Mistletoe" by Robert Dale is a collection of spells drawn from Celtic myth for use with RuneQuest. "Under Siege" by Joe Dever and Gary Chalk is a discussion of sieges in the context of miniatures wargaming, complete photographs.

"Slave Hunt" is this month's installment of "Fiend Factory." Like many of the early installments of the feature, editor Albie Fiore weaves a loose scenario around four new monsters for use with D&D. The new monsters, all submitted by different authors, are all small humanoid creatures of various kinds, none of them particularly notable in my opinion – but that's a common problem of new monsters for the game. Finally, there's "Bits and Pieces," a random collection of material for Dungeons & Dragons. While the material isn't particularly memorable, it's listed as having been collected by Roger E. Moore, who was already an editor at Dragon at the time and would go on to be its editor-in-chief in 1986.

This is another solid issue of White Dwarf with a diverse range of articles covering a variety of games. What I most notice is the growing presence of articles dedicated to Warhammer and miniatures wargaming more generally. This is a trend that will only increase in the coming years and eventually lead to the magazine's becoming explicitly a house organ of Games Workshop in a way that it hadn't been previously. It also would lead to my ceasing to read, since I read primarily for its coverage of D&D, Call of Cthulhu, and Traveller.

Planning a Holiday Soon?

Does anyone remember the Dungeon Planner Sets from Games Workshop? I remember seeing advertisements for them in White Dwarf but I never encountered them in the wild. I was very intrigued by the ads and likely would have purchased one of them had I ever seen them for sale in a store. Unfortunately, the ads were the closest I ever got to them, so I'd be curious to hear from anyone who did own one (or even just saw one).

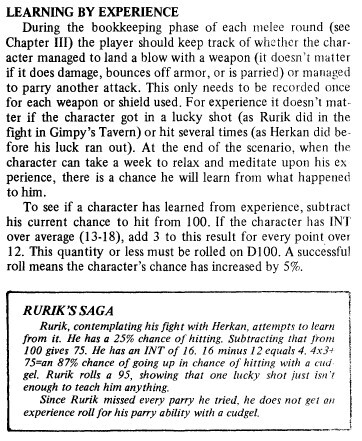

Learning by Experience

Consequently, I find myself being drawn more and more to the approach to experience in Chaosium's Basic Role-Playing family of games. Now, BRP is quite unlike D&D in its design, being almost entirely skill-based, so there are limits to the lessons that can be drawn from it. Even so, there's a lot I like about its design, such as learning by experience, as presented in this section from the second edition of RuneQuest:

This version of learning by experience is, in my opinion, more complicated than it needs to be in its specifics. Call of Cthulhu – at least in its classical version; I can't speak to the current edition – makes use of a simpler version. Other BRP games employ their own variations. What matters to me is the basic conception of tracking individual advancement in each area of character's competency (skills), not any particular implementation of it. Indeed, I think it might well be possible to come up with a simpler application of it that nevertheless retains the core idea.

This version of learning by experience is, in my opinion, more complicated than it needs to be in its specifics. Call of Cthulhu – at least in its classical version; I can't speak to the current edition – makes use of a simpler version. Other BRP games employ their own variations. What matters to me is the basic conception of tracking individual advancement in each area of character's competency (skills), not any particular implementation of it. Indeed, I think it might well be possible to come up with a simpler application of it that nevertheless retains the core idea.I don't know. My thinking is all over the place at the moment and I apologize if my recent spate of posts on experience and levels doesn't completely make sense. I suppose I am thinking aloud in order to decide what I like and want as I puzzle my way through the design of Secrets of sha-Arthan. Ultimately, my goal is a set of rules that is straightforward, if not not necessarily simple, and that is robust enough to handle a setting that's as culturally immersive as Glorantha, Jorune, or Tékumel (all of which are, to varying degrees, influences upon sha-Arthan).

As always, I appreciate your comments.

Know then, O Prince ....

Here's a TSR UK advertisement for the 1985 Conan Role-Playing Game. It's a disappointingly understated ad in my opinion, especially given the subject matter. That said, I have a strange affection for the game, which was, objectively speaking, nothing great, but my friends and I had fun with it and that's the true measure of any RPG.

(I feel compelled to point out that the tagline of the advertisement, which is ostensibly an excerpt from the Nemedian Chronicles quoted at the beginning of "The Phoenix on the Sword," is wrong. The adverb "then" does not appear in Howard's original text. Mind you, what follows below is itself a paraphrase, omitting certain words and praises, so perhaps we shouldn't judge this too harshly.)

October 9, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Devotee of Evil

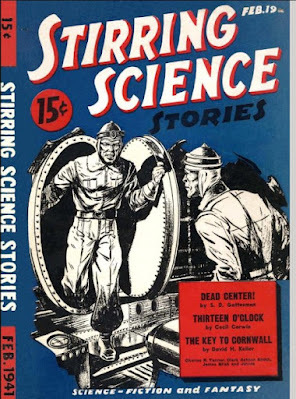

After last week's post, I thought it might be worthwhile to take a look at the third story featuring Clark Ashton Smith's author insert, Philip Hastane. Entitled "The Devotee of Evil," Smith finished writing it in early 1930 but had difficulty in finding a market for it. After failed submissions to Ghost Stories, Galaxy, Illustrated Detective Magazine, and the New Orleans Times-Picayune, he included it in his self-published The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies, which appeared in June 1933 (and also included the eponymous "The Double Shadow" and "The Maze of the Enchanter"). Almost a decade later, it re-appeared in the pages of the February 1941 issue of Stirring Science Stories.

After last week's post, I thought it might be worthwhile to take a look at the third story featuring Clark Ashton Smith's author insert, Philip Hastane. Entitled "The Devotee of Evil," Smith finished writing it in early 1930 but had difficulty in finding a market for it. After failed submissions to Ghost Stories, Galaxy, Illustrated Detective Magazine, and the New Orleans Times-Picayune, he included it in his self-published The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies, which appeared in June 1933 (and also included the eponymous "The Double Shadow" and "The Maze of the Enchanter"). Almost a decade later, it re-appeared in the pages of the February 1941 issue of Stirring Science Stories. The story concerns new owner of "the old Larcom house,"

a mansion of considerable size and dignity, set among oaks and cypresses on the hill behind Auburn's Chinatown, in what had once been the aristocratic section of the village. At the time of which I write, it had been unoccupied for several years and had begun to present the signs of desolation and dilapidation which untenanted houses so soon display. The place had a tragic history and was believed to be haunted.

This owner is one Jean Averaud of New Orleans (hence Smith's submission of the tale to the Times-Picayune). Averaud – whose name is reminiscent of the French province of Averoigne – is reputed to be "a recluse of the most eccentric type" as well as "extravagantly rich." He moves into Larcom House with his beautiful woman "who was believed to be his mistress as well as his housekeeper."

Hastane serves as the story's narrator and mentions that, before their first formal meeting, he had seen Averaud several times and made an assessment of him based on his appearance.

He was a sallow, saturnine Creole, with the marks of race in his hollow cheeks and feverish eyes. I was struck by his air of intellect, and by the fiery fixity of his gaze — the gaze of a man who is dominated by one idea to the exclusion of all else. Some medieval alchemist, who believed himself to be on the point of attaining his objective after years of unrelenting research, might have looked as he did.

In time, though, Averaud specifically seeks out Hastane, whose reputation as a novelist of the weird has elicited his admiration. When he finds him, Hastane is in the midst of reading an item in the local newspaper about an "atrocious crime," namely the murder of a woman and her two young children. Averaud takes note of this and uses it as an opportunity to philosophize on the subject of evil.

"I believe in evil — how can I do otherwise when I see its manifestations everywhere? I regard it as an all-controlling power; but I do not think that the power is personal in the sense of what we know as personality. A Satan? No. What I conceive is a sort of dark vibration, the radiation of a black sun, of a center of malignant eons — a radiation that can penetrate like any other ray — and perhaps more deeply. But probably I don't make my meaning clear at all."

To the contrary, Hastane understands his meaning quite well and is intrigued by his musings. Some time later, Averaud invites the novelist to Larcom House, an offer he accepts, in part to sate his curiosity about both the ancient building and its newest inhabitants. In Averaud's library, he finds "an ungodly jumble of tomes," dealing with "anthropology, ancient religions, demonology, modern science, history, psychoanalysis and ethics. Interspersed with these were a few romances and volumes of poetry. Beausobre's monograph on Manichaeism was flanked with Byron and Poe; and "Les Fleurs du Mal" jostled a late treatise on chemistry."

"You have been looking at my books," he observed immediately. "Though you might not think so at first glance, on account of their seeming diversity, I have selected them all with a single object: the study of evil in all its aspects, ancient, medieval and modern. I have traced it in the religions and demonologies of all peoples; and, more than this, in human history itself. I have found it in the inspiration of poets and romancers who have dealt with the darker impulses, emotion and acts of man. Your novels have interested me for this reason: you are aware of the baneful influences which surround us, which so often sway or actuate us. I have followed the working of these agencies even in chemical reactions, in the growth and decay of trees, flowers, minerals. I feel that the processes of physical decomposition, as well as the similar mental and moral processes, are due entirely to them.

"In brief, I have postulated a monistic evil, which is the source of all death, deterioration, imperfection, pain, sorrow, madness and disease. This evil, so feebly counteracted by the powers of good, allures and fascinates me above all things. For a long time past, my life-work has been to ascertain its true nature, and trace it to its fountain-head. I am sure that somewhere in space there is the center from which all evil emanates."

Averaud further explains that his studies have led him to believe that "certain localities and buildings, certain arrangements of natural or artificial objects, are more favorable to the reception of evil influences than others." He adds that he has a theory that, because of some manner of "interference with the direct flow of malignant force," there has never been an instance of "pure, absolute evil" manifesting itself in the world, only echoes of varying degrees of potency.

Averaud intends to initiate an experiment that test this theory. He tells Hastane that

"By the use of some device which would create a proper field or form a receiving station, it should be possible to evoke this absolute evil. Under such conditions, I am sure that the dark vibration would become a visible and tangible thing, comparable to light or electricity." He eyed me with a gaze that was disconcertingly exigent. Then:

"I will confess that I have purchased this old mansion and its grounds mainly on account of their baleful history. The place is unusually liable to the influences of which I have spoken. I am now at work on an apparatus by means of which, when it is perfected, I hope to manifest in their essential purity the radiations of malign force."

Hastane soon takes his leave of Averaud, unsure of just what to think about the eccentric fellow and his plans. Though fascinated by Averaud's notions about the true nature of evil, he is less certain about the feasibility – not to mention desirability – of finding a means of manifesting pure, absolute evil in the world. The remainder of the story details what happens when Hastane returns to Larcom House to witness a supposed demonstration of a device invented by Averaud for this very purpose – and the consequences of its operation.

"The Devotee of Evil" is frequently criticized as little more than an imitation of better works of H.P. Lovecraft. While I can understand why one might make such criticisms, I don't think they're entirely fair. Certainly, the story is not one of Smith's best – it's much too short to do justice to its intended subject, for example – but its central conceit, the idea of evil as a fundamental force of the universe akin to those of the Standard Model of particle physics is a genuinely clever idea. Indeed, it's one I'd love to see developed further in one form or another. Consequently, I have some fondness for "The Devotee of Evil" and recommend it as an all-too-brief examination of a chilling notion.

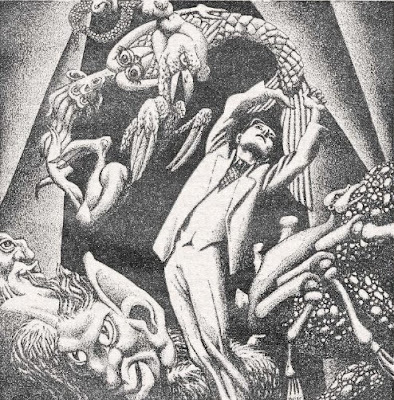

An illustration by the great Hannes Bok that accompanied the story

An illustration by the great Hannes Bok that accompanied the story

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers