James Maliszewski's Blog, page 100

September 13, 2022

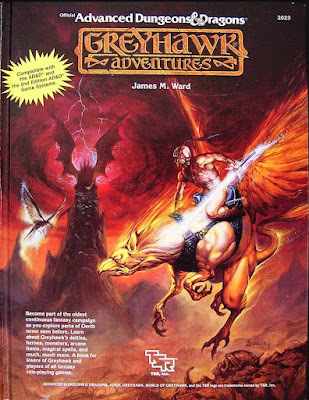

Retrospective: Greyhawk Adventures

Although D&D's Bronze Age in the early to mid-1990s is quite rightly associated with the plethora of pre-packaged campaign settings TSR published for the game, this strategy had its origins in the dying days of the Silver Age. This was the period immediately prior to the release of David Cook's second edition of AD&D, when the company was throwing a lot of spaghetti against a lot of walls to see what might stick. The time was equal parts "experimental" and "desperate" and you can see that in the unevenness of the products TSR created.

Although D&D's Bronze Age in the early to mid-1990s is quite rightly associated with the plethora of pre-packaged campaign settings TSR published for the game, this strategy had its origins in the dying days of the Silver Age. This was the period immediately prior to the release of David Cook's second edition of AD&D, when the company was throwing a lot of spaghetti against a lot of walls to see what might stick. The time was equal parts "experimental" and "desperate" and you can see that in the unevenness of the products TSR created.Being the unrepentant TSR fanboy I was, I naturally picked up almost everything the company produced, even when it wasn't something out of which I thought I'd get much use. That's what led me to buy Dragonlance Adventures in 1987 and, the following year, Greyhawk Adventures. In 1988, I was no longer making use of Gary Gygax's World of Greyhawk setting, having developed my own setting during my high school years. Even so, there was no way I wasn't going to grab a new hardcover AD&D book, especially one written by James M. Ward, creator of my beloved Gamma World.

As it would turn out, Greyhawk Adventures is not the work of James M. Ward – or, rather, it's not solely his work. The volume is instead the work of many different writers, some of whose names I recognize and others completely unknown to me: Daniel Salas, Skip Williams, Nigel Findley, Thomas Kane, Stephen Innis, Len Carpenter, and Eric Oppen. The content of the book is itself a mixed bag, consisting of seven chapters and two appendices. The chapters describe (in order) the deities and clerics of Greyhawk, new monsters, significant named NPCs, magic spells, magic items, unusual locales, and a series of adventure outlines and random encounters. Meanwhile, one appendix enumerates the spells named after Greyhawk magic-users and the other introduces the concept of playable 0-level characters.

The section on deities and clerics was of great interest to me in my youth, in part because I had a lot of fondness for the gods of Greyhawk. Each god is described in some detail, along with the statistics for his "avatar" or physical manifestation in the realm of mortals. I suspect this concept was introduced here in order to obviate the problems that arose from the way the gods had been presented in Ward's earlier Deities & Demigods. Clerics, on the other hand, were presented in a way similar to Dragonlance Adventures, with each god's priesthoods operating according to their own unique rules, including weapon and spell restrictions. I thought then as I do now that this only makes sense and probably should have been introduced into Dungeons & Dragons sooner. If nothing else, it's an excellent example of game mechanics doubling as worldbuilding.

Sadly, after a strong first chapter, Greyhawk Adventures stumbles and never really recovers. The sections on monsters and magic items, for example, are fairly bland, with only the thinnest of Greyhawk veneers to justify their inclusion in this book. The section on named NPCs, many of whom are the rulers of the setting's city-states and countries, is a little better in that there's a stronger connection to the setting but most of these NPCs are so powerful and influential that the likelihood of a DM ever making use of them in play is small. The book's many new spells, like everything else in this book, vary in quality, their main characteristic being that all of them are associated with a famous Greyhawk spellcaster. If you ever wanted more Bigby's Hand spells, for example, Greyhawk Adventures has got you covered.

After all these years, I still can't make up my mind as to whether the idea of playable 0-level characters is insanity or genius. The basic idea is that a 0-level character is an apprentice adventurer, one who hasn't yet decided on his character class. Through his choices, the 0-level character slowly determines his alignment, abilities, proficiencies, and so on. He can also seek out instructors to teach him more, thereby advancing along the road toward full membership in a traditional character class. It's a genuinely interesting idea, particularly since 0-level characters can and indeed will have a smattering of skills associated with multiple classes. It's almost an attempt to present a class-less AD&D, albeit one with lots of caveats and limitations in order to preserve one of the game's foundational design elements. (It's worth noting, too, that there are also rules for allowing characters of 1st level and above to pick up the abilities of other classes at the cost of an XP penalty.)

Compared to Dragonlance Adventures, Greyhawk Adventures is a letdown on multiple levels. The strength of Dragonlance Adventures lies in its integration of rules and setting so as to present a version of AD&D tailored to the world of Krynn. Greyhawk Adventures does nothing of the kind. It's a grab-bag of fairly generic – and often unimaginative – material released under the Greyhawk masthead but without any significant connection to Gygax's campaign setting. The most interesting stuff in the book, aside from the material on the gods and their clerics (which was simply an adaptation of what Dragonlance Adventures had already done), is the appendix on 0-level characters and even that is half-baked and tentative, as if its designer (whoever he was) didn't quite have the courage of his conviction to upend D&D's class system entirely.

The end result is a book that is by turns meandering, trite, and directionless – much like TSR before the publication of Second Edition gave the company a short-lived injection of energy and enthusiasm. As a well known hater of Dragonlance, I hope others will recognize the significance of my stating here that Dragonlance Adventures was a superior book to Greyhawk Adventures in almost every way. Indeed, it's possible that Greyhawk Adventures might well be the worst hardcover volume ever published for the first edition of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, which is saying something.

September 8, 2022

The Eternal Paradox

Random Lonely Nerd: "I wish more people were interested in [comic books/Star Trek/Dungeons & Dragons/etc.]."

Random Annoyed Nerd: "It was better before more people became interested in [comic books/Star Trek/Dungeons & Dragons/etc.]."

Random Annoyed Nerd: "It was better before more people became interested in [comic books/Star Trek/Dungeons & Dragons/etc.]."September 6, 2022

I Slay, and Am Content

A mighty-thewed barbarian, courtesy of the incomparable Russ Nicholson (White Dwarf #49).

September 5, 2022

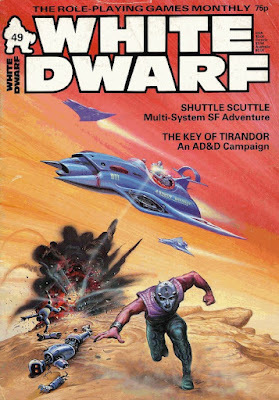

White Dwarf: Issue #49

Issue #49 of White Dwarf, with its cover by Angus McKie, is dated January 1984. Editor Ian Livingstone uses this (in)auspicious date to muse briefly about George Orwell's influential novel and the role RPGs might play in fending off Big Brother. He suggests that "role-playing games allow their players freedom of expression as no others have done before them." Even given the context in which he said it, the comment strikes me as naïve. Like Michael Moorcock, I'm not as certain as Livingstone that Big Brother would necessarily oppose the escapism of RPGs, since it might help to distract one from the shackles of everyday life under an oppressive regime. On the other hand, I suspect Livingstone didn't mean the comment seriously and so I won't dwell on it further here.

Issue #49 of White Dwarf, with its cover by Angus McKie, is dated January 1984. Editor Ian Livingstone uses this (in)auspicious date to muse briefly about George Orwell's influential novel and the role RPGs might play in fending off Big Brother. He suggests that "role-playing games allow their players freedom of expression as no others have done before them." Even given the context in which he said it, the comment strikes me as naïve. Like Michael Moorcock, I'm not as certain as Livingstone that Big Brother would necessarily oppose the escapism of RPGs, since it might help to distract one from the shackles of everyday life under an oppressive regime. On the other hand, I suspect Livingstone didn't mean the comment seriously and so I won't dwell on it further here.

"Shuttle Scuttle" by Thomas M. Price is a great example of two things White Dwarf regularly published: scenarios involving two or more groups of players and scenarios with game stats for two or more different game systems. In this case, it's a science fiction adventure for two groups of Traveller, Space Opera, or Laserburn players. One group consists of terrorists who've hijacked a shuttle – and the pilot of the shuttle; the other are government representatives trying to deal with the situation. Each group is supposed to convene in a separate room, with the referee moving between them, in order to represent the inability of each side to know fully what the other is saying or doing. That's interesting enough, but even more interesting is that the shuttle pilot in the first group is actually antagonistic to the terrorists in his "group" and must work to aid the government representatives in the other group without endangering the lives of any hostages aboard the shuttle. It's a compelling set-up for an adventure and, having done similar things in other RPGs to some success, I'm intensely curious how well it'd work in this case.

"Open Box" begins with a review of Monster Manual II, which receives 7 out of 10 – an entirely fair rating, despite my own personal fondness for the book. Two new Fighting Fantasy books are also reviewed, Starship Traveller (9 out of 10) and City of Thieves (8 out of 10). As I happened, I owned both of these and thought very highly of them, particularly the former, since I have always been more of a science fiction fan than a fantasy one. Also reviewed are three Traveller products: Supplement 12 – Forms and Charts (2 out of 10), Supplement 13 – Veterans (3 out of 10), and Adventure 9 – Nomads of the World Ocean ( 9 out of 10). Although I think the scores of the two supplements are a little harsh, I can understand why they were rated so poorly. On the other hand, Nomads of the World Ocean is a true classic and wholly deserving of its high score. Finally, there are reviews of Mercenaries. Spies, and Private Eyes (4 out of 10) and The Adventure of the Jade Jaguar (3 out of 10). This is probably the most negative installment of "Open Box" I've seen in some time. I wonder if it represents a course correction from the more usually glowing reviews of past issues.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" features reviews of multiple fantasy and science fiction novels, most notably Michael Ende's The Neverending Story. I'm honestly quite surprised Langford enjoyed the book (though not without a few of his usual jabs). "Clay to Marble" by Chris Felton is an expansion of sorts to the rules for construction in the Dungeon Masters Guide. Felton fleshes out things like costs, man-weeks, maintenance, and mishaps. Articles like this are a godsend to referees who care deeply about their subject matter but an awful bore to those who could care less. That's not a knock against the article itself, which is well done, only a comment on just how hard it must have been to find content for publication in a gaming magazine that might appeal to a wide audience.

"Runes in the Dungeon" by Dave Morris is a collection of variant rules for RuneQuest in which he presents "classes" for use with the game. These classes are fighters, magic-users, thieves, and witches and each includes special rules for generating ability scores and starting skills. The intent here is not so much to abandon RQ's traditional rules structure as to scaffold an occupation-based approach to creating a character. This is especially helpful, I'd imagine, to players accustomed to D&D's approach to character generation, as well as those who simply need the spark of creativity in creating a new character. I think it's a great little article. Meanwhile, "Rune Questions" by Oliver Dickinson is simply a collection of questions and answers about the rules of RuneQuest and the world of Glorantha.

"A Fleeting Encounter" by Andy Slack is a great Traveller article that offers advice on expanding the simpler starship rules of Book 2 so that the referee isn't required to delve into the complexities of the High Guard supplement. This is something of which I approve, since I always found High Guard too much of a muchness for my taste. We also get new strips for "Thrud the Barbarian," "The Travellers," and "Gobbledigook," with "The Travellers" being my favorite, of course. As I believe I've explained before, what makes "The Travellers" stand out for me is the way it amusingly presents what it's like to have played in a Traveller campaign in the 1980s, right down to the shameless ripping off of plots and situations from SF books, TV shows, and movies.

"The Key of Tirandor" by Mike Polling is the first part of a two-part AD&D adventure for characters of levels 6–9. What makes it especially notable is that the adventure – though the text calls it a "campaign" – takes place in its own unique setting, one that is low in magic and where there are no real gods (and thus no clerics), though peasants and the ignorant believe in their existence. The setting also has its own unique monsters, which are described at the end of this part of the adventure. It's very fascinating stuff and, from the vantage point of the present day, quite compelling, since I've lately found myself wishing more fantasy RPG settings were similarly original in their presentation.

"The Goblin Cult of Kernu" by Ian Bailey is a follow-up to his presentation of goblins for use with RuneQuest in issue #46. Here, as the article's title suggests, Bailey gives readers an example of a goblin cult for use in the game, along with sub-cults and a spirit associated with them. "Insect World" collects five new creepy crawlies for use with D&D or AD&D, while "Detect Illusion" does the same for new spells and magic items associated with the illusionist class. There's also a strangely uninteresting installment of "Super Mole," White Dwarf's games gossip column. Most of the rumors presented aren't at all intriguing, with the exception of the story of Will Niebling's attempt to exercise a stock option for 500 shares that was rejected by Brian Blume and might result in a lawsuit. I know nothing more about this supposed dispute, but I imagine it reflects the chaos and decline that characterized mid-1980s TSR.

Issue #49 is a very good issue and I greatly enjoyed its contents, as the length of this post attests. Next week, we reach the half-century mark in the history of White Dwarf and, if my middle-aged memory is correct, it's another pretty decent issue.

August 31, 2022

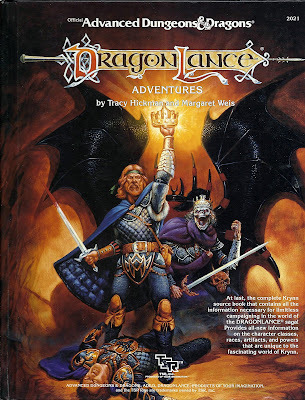

Retrospective: Dragonlance Adventures

Although there are nearly four thousand posts on this blog, one of the most widely read remains "How Dragonlance Ruined Everything," published all the way back in 2008. Though the title is intentionally hyperbolic, I largely stand behind what I wrote then, namely that the release and success of the Dragonlance series of adventure modules was the crowning achievement of the Hickman Revolution and forever changed the trajectory of Dungeons & Dragons. I don't think this is disputable. Since 1984, D&D – and indeed roleplaying games in general – have been slowly evolving into a much more story-driven, character-focused form of entertainment than the by-blow of miniatures wargaming it was in 1974. Whether one views this evolution as good or bad is irrelevant to the truth of it.

Although there are nearly four thousand posts on this blog, one of the most widely read remains "How Dragonlance Ruined Everything," published all the way back in 2008. Though the title is intentionally hyperbolic, I largely stand behind what I wrote then, namely that the release and success of the Dragonlance series of adventure modules was the crowning achievement of the Hickman Revolution and forever changed the trajectory of Dungeons & Dragons. I don't think this is disputable. Since 1984, D&D – and indeed roleplaying games in general – have been slowly evolving into a much more story-driven, character-focused form of entertainment than the by-blow of miniatures wargaming it was in 1974. Whether one views this evolution as good or bad is irrelevant to the truth of it.Consequently, it should come as no surprise that, as Dragonlance's star rose ever higher, TSR would attempt to use it as a platform to change the game mechanically as well as conceptually. Dragonlance Adventures demonstrates precisely what I mean. Published in 1987, DLA is a 128-page hardcover volume on the model of previous AD&D tomes like the Players Handbook. Though billed as a "source book," its content is not simply setting material; the book contains many new rules that augment or outright replace those of standard AD&D. In fact, many of these new rules, as we'll see, appear to be dry runs for rules that would later be incorporated into Second Edition when it appeared in 1989.

The most obvious changes in Dragonlance Adventures come in the form of its character classes. Almost every standard AD&D class is either altered or replaced in DLA, the only exceptions being fighter, barbarian, ranger, thief, and thief/acrobat. Consequently, the book provides quite a few new classes, such as three different types of clerics, wizards, and Knights of Solamnia, all of which tie closely into the history and cosmology of the world of Krynn. Also presented is the tinker class for use by the setting's unique take on gnomes. Other nonhuman races are similarly reimagined or, in the case of halflings, replaced entirely (which has the added benefit of severing some of D&D's most direct connections to Tolkien's Middle-earth – there are no orcs on Krynn, for example).

Though these changes, as I note, are presented in order to bring the rules more into line with the realities of the setting, they also enable Tracy Hickman, who is credited as the book's "designer," to tinker with some of AD&D's rules in ways that, at the time, were genuinely original. For example, the three types of wizards – White, Red, and Black – are distinguished not simply by their alignment, but also by which "spheres" of magic to which they have access. These spheres are simply AD&D's schools of magic (abjuration, conjuration, etc.) renamed. The effect of this change is to differentiate wizards by their background and training, much in the way that Second Edition would do with specialist wizards. Similarly, clerics would have access to different spheres of spells based on the interests of the gods they served.

The mechanical treatment of Krynn's races is quite similar, fiddling as it does with the verities laid down in the Players Handbook. Not only does Hickman shift the ability score ranges, he alters both the availability of classes and, more significantly, their level limits. Silvanesti Elves, for instance, can be paladins and they're unlimited in their advancement, two remarkable deviations from the Gygaxian canon of earlier AD&D. There are also rules for playing minotaurs, who, while brutal, are not inherently evil or unintelligent – another notable shift away from the "facts" of the game as it was known at the time.

From the vantage point of present day D&D, filled as it is with innumerable new character classes, nonhuman species, and nary a level limit to be seen, none of this likely appears worthy of mention, let alone suspicion. Yet, at the time, these tentative steps away from the humanocentric, pulp fantasy picaresque of Golden Age D&D were truly revolutionary, especially coming from TSR, which had previously resisted – and, under Gygax, mocked – any such attempts to upend the game's presentation and focus. A great many people, myself included, welcomed these changes and felt that they presaged a a great sea change in the game. As it turned out, we were more prescient than we realized and Dragonlance Adventures served as the herald of the new age aborning, just as the Dragonlance adventure modules had done several years previously.

There's a lot more that could be said about this book and the role it played in changing the design of AD&D, such as its inclusion of the non-weapon proficiencies of the Dungeoneer's and Wilderness Survival Guides as baseline features of the rules. While I don't want to minimize the significance of their inclusion, even more significant, I think, is the overall presentation of DLA, which offers the reader – more on that in a moment – a coherent setting whose rules are designed to emulate and reinforce its flavor and themes. Krynn is explicitly a setting that "promot[es] the power of truth over injustice, good over evil, and grant[s] good consequences for good acts and bad consequences for evil acts." The Angry Mothers from Heck would be pleased.

Let me conclude with a brief note about the book's preface, which states that "you can certainly enjoy this book without playing the game." Though Hickman and Weis quickly enjoin the reader to play, I think it's significant that the preface even countenances the idea that one might buy Dragonlance Adventures without wishing to play AD&D. We must remember how popular – and lucrative – the Dragonlance novels were and how many people became fans of the setting and its characters as a result. I'd wager that, while Dragonlance was very profitable for TSR, the number of new players it introduced to playing D&D was not nearly as great. Dragonlance (and, by extension, D&D) was a powerful brand and that's all that mattered. Once again, Dragonlance was a forerunner of what was to come.

August 30, 2022

White Dwarf: Issue #48

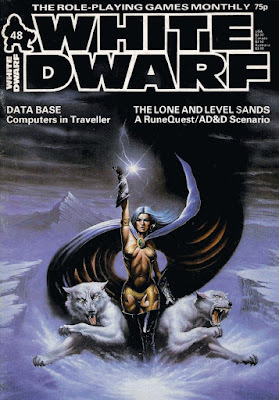

Issue #48 of White Dwarf (December 1983) boasts what is, I suppose, a winter-themed cover illustration by Alan Craddock, though someone ought to give the poor woman something a bit warmer to wear! The issue begins with "Open Box," in which a passel of game products are reviewed, starting with several D&D and AD&D modules. They are Beyond the Crystal Cave (9 out of 10), Dungeonland (9 out of 10), The Land Beyond the Magic Mirror (9 out of 10), and Curse of Xanathon (7out of 10). The Traveller Starter Edition is given 8 out of 10, because it lacked a few things (rules for drugs and self-improvement) that other editions of the game included. Two adventures for use with Call of Cthulhu (published by TOME), Arkham Evil and Death in Dunwich score 7 and 8 out of 10 respectively. Finally, there are reviews of Autoduel Champions and the Car Wars Reference Screen, rated at 8 and 6.

Issue #48 of White Dwarf (December 1983) boasts what is, I suppose, a winter-themed cover illustration by Alan Craddock, though someone ought to give the poor woman something a bit warmer to wear! The issue begins with "Open Box," in which a passel of game products are reviewed, starting with several D&D and AD&D modules. They are Beyond the Crystal Cave (9 out of 10), Dungeonland (9 out of 10), The Land Beyond the Magic Mirror (9 out of 10), and Curse of Xanathon (7out of 10). The Traveller Starter Edition is given 8 out of 10, because it lacked a few things (rules for drugs and self-improvement) that other editions of the game included. Two adventures for use with Call of Cthulhu (published by TOME), Arkham Evil and Death in Dunwich score 7 and 8 out of 10 respectively. Finally, there are reviews of Autoduel Champions and the Car Wars Reference Screen, rated at 8 and 6.Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" brief tackles a number of different books this month, including novels by Robert Silverberg, Tanith Lee, and Brian Aldiss. One of the things I always liked about Langford's reviews was the coolness of his praise, while his criticisms frequently ran very hot indeed. Nowadays, I find his reviews a bit more mean-spirited than I did in my youth, but that probably says more about my middle-aged softness than it does about Langford, many of whose reviews are still fun to read.

"By the Gods!" is a short article by Lewis Pulsipher – did he write something for every issue of White Dwarf? – in which he touches on the questions of the extent to which the gods might involve themselves in the outcome of mortal battles. Pulsipher marshals several arguments, based largely on Earth mythology, that the gods won't interfere much, but I'm not convinced myself. After all, why should the gods of a fantasy world follow the pattern laid down in The Iliad or Norse sagas rather than a logic all their own? That said, I understand why he offered this answer and am somewhat sympathetic to it. On the other hand, divine intervention is a possibility in many fantasy RPGs and it seems a shame not to consider it.

"Stomp!" is a fun little article by Rick Priestley, in which he presents rules for adding giants into Warhammer Fantasy Battles. Of particular amusement is the section entitled "Giants and Alcohol," which explains that "giants have a very irresponsible attitude towards alcohol" and then notes that elves believe this is due to "'environmental factors' and 'widespread social and economic deprivation'." Because giants are likely to be drunk when encountered, the article provides procedures for simulating their staggered movement. As I said, it's great fun and a pleasant reminder of when fantasy gaming put greater stock in whimsy and humor.

"The Dark Brotherhood" by Chris Felton is a collection of advice on better integrating assassins into an ongoing AD&D campaign, along with sketches of a few scenarios involving this deadly character class. The article is nothing special, but not everything in an issue is going to be gold, is it? "The Game of the Book …" by Charles Vasey touches on the extent to which various wargames accurately reflect the books that inspired them. This is a topic of some interest to me, though my lack of direct familiarity with many of the games Vasey cites limits it utility to me.

"Database" by Marcus L. Rowland is a sensible expansion of the computer rules in Traveller, something that nearly everyone who played the game felt was necessary. Even in the early 1980s, before personal computers were ubiquitous, gamers found Traveller's approach to the topic inadequate, leading to a plethora of articles like this one. "Ice, Desert, and Swamp" presents three new monsters for use with RuneQuest, including the Cactus Devil, show here:

"The Lone and Level Sands" by Dave Morris and Oliver Johnson is a scenario for use with both AD&D and RuneQuest. As I recall, this was a common practice in the pages of White Dwarf, suggesting, I think, just how popular RQ had become in Britain by this time. The scenario itself involves a trek across the desert to explore a partially buried temple complex, populated with all manner of deadly enemies, including several that appear in this issue's "Fiend Factory" installment. The whole thing is atmospheric and well done, but then I'm a sucker for a good old fashioned excavation in the desert sands.

"The Lone and Level Sands" by Dave Morris and Oliver Johnson is a scenario for use with both AD&D and RuneQuest. As I recall, this was a common practice in the pages of White Dwarf, suggesting, I think, just how popular RQ had become in Britain by this time. The scenario itself involves a trek across the desert to explore a partially buried temple complex, populated with all manner of deadly enemies, including several that appear in this issue's "Fiend Factory" installment. The whole thing is atmospheric and well done, but then I'm a sucker for a good old fashioned excavation in the desert sands."The Demonist's Grimoire" by Phil Masters is a collection of new spells for use with the demonist class introduced in issue #47. I wish I could say that any of the spells was so good that it changed my mind about the utility of the class itself. Instead, this is just another filler article of the sort that all gaming magazines published regularly. Fortunately, there are more installments of the comics "Gobbledigook," "Thrud the Barbarian," and "The Travellers" to keep me happy.

Issue #48 is perhaps a bit of a letdown compared to its immediate predecessors. That was probably inevitable, since issue #47 marked the conclusion to the excellent "Irilian" series and there was nothing this time to rival it. Even so, the AD&D/RQ adventure is memorable and the Traveller article welcome. With luck, issue #49 might better grab my attention.

August 29, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Sunken Land

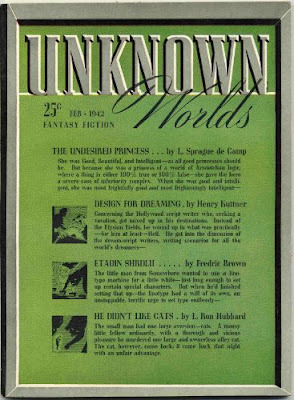

Originally published in the February 1942 issue of Unknown Worlds, "The Sunken Land" is an early adventure of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser (the fourth in terms of publication). Consequently, it's somewhat shorter than many of his later and more famous tales of the Twain. I don't mind this in the least, as my patience with the ever-increasing length of fantasy and science fiction literature grows thinner with each passing year. The plot of "The Sunken Land" also seems somewhat derivative of other earlier works, such as Lovecraft's "Dagon" and Smith's "The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis." Again, I don't mind this, as I think "originality" is over-valued when it comes to fiction. In addition, both of the aforementioned stories are fine evocations of supernatural horror, which I consider an important part of what makes a good sword-and-sorcery yarn (as opposed to mere "fantasy").

Originally published in the February 1942 issue of Unknown Worlds, "The Sunken Land" is an early adventure of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser (the fourth in terms of publication). Consequently, it's somewhat shorter than many of his later and more famous tales of the Twain. I don't mind this in the least, as my patience with the ever-increasing length of fantasy and science fiction literature grows thinner with each passing year. The plot of "The Sunken Land" also seems somewhat derivative of other earlier works, such as Lovecraft's "Dagon" and Smith's "The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis." Again, I don't mind this, as I think "originality" is over-valued when it comes to fiction. In addition, both of the aforementioned stories are fine evocations of supernatural horror, which I consider an important part of what makes a good sword-and-sorcery yarn (as opposed to mere "fantasy"). "The Sunken Land" begins with Fafhrd and the Mouser aboard a "cranky sloop," as it makes its way across the "huge, salty Outer Sea" en route to Lankhmar. While the Mouser is unhappy about their maritime journey – something about the "uniformly stormless weather and favorable winds disturbed him" – Fafhrd is having the time of his life. His people are renowned sailors and he enjoyed being once more aboard the deck of a ship. More than that, his bow-fishing had brought him an unexpected boon. The belly of one of the fish he's reeled in contains a prize.

The object did not seem very small even on Fafhrd's broad palm, and although slimed-over a little, was indubitably gold. It was both a ring and a key, the key part set at a right angle, so that it would lie along the finger when worn, There were carvings of some sort. Instinctively the Gray Mouser did not like the object. It somehow focused the vague unease he had felt for several days now.

Naturally, Fafhrd does not share his friend's pessimistic view. Indeed, he proclaims that he "was born with luck as a twin" and proudly displays the ring on his hand. Despite this, something about the ring roused "strange memories" in Fafhrd, perhaps due to the fact that the carving on the ring "represented a sea monster dragging down a ship."

"I think they called the land Simorgya. It sank under the sea ages ago. Yet even then my people had gone raiding against it, though it was a long sail out and a weary beat homeward. My memory is uncertain. I only heard scraps of talk about it when I was a little child. But I did see a few trinkets carved somewhat like the ring, just a very few. The legends, I think, told that the men of far Simorgya were mighty magicians, claiming power over wind and waves and the creatures below. Yet the sea gulped them down for all that."

The Mouser takes an interest in these legends and suggests that perhaps they now sail over top the sunken land of Simorgya. If so, would it not be better if Fafhrd threw the ring overboard? Who knows what curse might be laid upon it? Later, as if to prove the Mouser right, a strange storm blows up and he once again urges his friend to get rid of the ring. Even stranger, Fafhrd sees something appear out of the storm – "the dragon-headed prow of a galley."

Needless to say, neither expected to see another ship come upon theirs in the middle of such a terrible storm, especially not a ship that resembled that of Fafhrd's own people. The sight of it so catches the big barbarian off-guard that, for once, he fails to pay attention to his surroundings aboard the deck and is knocked overboard. Adrift on the stormy sea at night, Fafhrd loses sight of the sloop on which he was traveling – and the Mouser. In time, he is rescued by the crew of the galley, who were "Northerners akin to himself. Big raw-boned fellows, so blond they seemed to lack eyebrows."

The Northerners did not save him out of any kindness. They need an oarsman to replace one of their own who had been swept into the sea during the storm. Like Fafhrd's discovery of the ring in the fish's belly, he himself has become an unexpected gift to his rescuers. Put to work, Fafhrd learns from another oarsman that the leader of the Northerners, Lavas Laerk, had "sworn to raid far Simorgya," the exact same legendary land about which Fafhrd has spoken to the Mouser earlier. Quite a coincidence! Even more remarkable is the fact that, sometime thereafter, the ship's steersman cries out, "Land ho! Simorgya! Simorgya!" Somehow, against all odds – against all reason – the Northerners had found Simorgya, a magical land supposedly sunk beneath the waves ages ago …

"The Sunken Land" is a terrific bit of economical but nevertheless engaging storytelling. It's more of a ghost story than a typical sword-and-sorcery tale of rollicking adventure but that doesn't take away from my pleasure in reading it. Leiber is a master of mood and creeping horror and he puts that mastery to good use in "The Sunken Land." It's a great reminder that horror is a species of fantasy and it ought not be neglected, either in literature or fantasy roleplaying games.

August 25, 2022

In Defense of the Killer DM

One of the unique – and often frustrating – things about roleplaying games as a form of entertainment is how variable one's experience of them can be. More so than other types of games, one's enjoyment of an RPG is heavily dependent on the referee. In this, an imaginative, quick-thinking referee is every bit as important as solid rules. Of course, imaginative, quick-thinking players are vital too, but, for the purposes of this post, I want to focus on the referee.

One of the unique – and often frustrating – things about roleplaying games as a form of entertainment is how variable one's experience of them can be. More so than other types of games, one's enjoyment of an RPG is heavily dependent on the referee. In this, an imaginative, quick-thinking referee is every bit as important as solid rules. Of course, imaginative, quick-thinking players are vital too, but, for the purposes of this post, I want to focus on the referee.If a good referee contributes to one's enjoyment of a roleplaying game, it stands to reason that a bad one can detract from it. I don't think this is controversial, though I suspect there's likely disagreement over just what constitutes a "bad" referee. Even so, I frequently hear criticism of a particular species of bad referee, the so-called "Killer DM." The Killer DM is the kind of referee who supposedly delights in torturing the characters in his campaign by presenting them with unfair fights and unavoidable traps, not to mention belligerent and unhelpful NPCs. He's a cruel tyrant rather than the impartial arbiter demanded by the role of referee.

Fear of the Killer DM is widespread – so widespread, in fact, that many RPGs not only contain explicit admonitions against the types of behaviors that are the purported hallmarks of the species, but often design their rules in such a way as to give them rather than the referee the final say on how things are to be adjudicated in the game. Lest anyone think this is simply a grognardly rant against "kids today," I am quick to point out that fear of the Killer DM goes back decades and the changes to the presentation of games I mention above are almost as old.

Nevertheless, I do think that fear – or at least vocal disapproval – of the Killer DM is more commonplace than ever, despite (or perhaps because of) the near-extinction of the species. Roleplayers continue to talk about the Killer DM as if one were likely to encounter him lurking beneath every gaming table, waiting for his chance to strike, but how often is he actually seen in the wild in the 21st century? In my experience, the Killer DM is now mostly a myth and a cautionary tale rather than an ever-present danger against whose sadistic power-trips games must be designed to guard.

All that said, I'd like to come to the defense of the Killer DM, or at least to that sub-species of him I encountered several times over the course of my decades in the hobby and for whom I retain a certain affection. The most memorable example of the Killer DM of my acquaintance was a childhood friend's teenaged older brother. He, along with their father, would sometimes referee adventures for us and it was always a struggle to survive them. There was also an older fellow who'd regularly show up to the local library's games days and referee an incredibly deadly dungeon crawl for anyone who dared to take a seat at his table. My old college roommate was cut from similar cloth and I distinctly remember many hours spent braving his insidious labyrinths.

Two things unite all these referees. First, they ran their games in a ruthless fashion and definitely took delight in watching characters suffer as a result of the bad decisions of their players. Second, their games were a lot of fun, in large part because they were a challenge. Whereas nowadays I think the emphasis is placed more on the roleplaying aspect of RPGs, in the past it was not at all uncommon to find who referees who emphasized the game aspect. For referees of this sort, an adventure was a battle of wits (and luck) between the referee and the players. Their fun was had in coming up with cleverly fiendish ways to test the intelligence, imagination, and perseverance of the players – and I can attest to the fact that it was indeed fun.

I don't think there's as much interest in (or tolerance for) this style of play anymore. This is the culture out of which things like Grimtooth's Traps arose and, if you know that legendary product, you might have better insight into the kind of Killer DM of whom I am still fond. The games these referees ran are not my preferred style of play, then or now. Yet, I find myself regularly reminded of them and the joy my friends and I took in occasionally besting them on their home turf. I think even they secretly enjoyed seeing us grind out a hard-earned victory once in a while, because they knew better than anyone how difficult it was to do that.

Tom Moldvay claimed in his Basic Rulebook that "winning" and "losing" didn't apply to D&D – but that's only because he never played with my friend's older brother. Anyone whose character made it out of one of his dungeons alive knew well what it meant to win.

D&D Fatigue

Except for a period in the 1990s, Dungeons & Dragons has always been the most popular and bestselling RPG (and, before anyone mentions Pathfinder's brief ascension during the 4e debacle, I pre-emptively respond: Pathfinder is D&D). D&D is most people's introduction to the hobby of roleplaying; it's also the only RPG that non-gamers know by name. D&D is thus the proverbial 800-lb. gorilla of roleplaying games. In a very real sense, the entirety of the hobby (and the industry supporting it) owes its very existence to D&D.

Except for a period in the 1990s, Dungeons & Dragons has always been the most popular and bestselling RPG (and, before anyone mentions Pathfinder's brief ascension during the 4e debacle, I pre-emptively respond: Pathfinder is D&D). D&D is most people's introduction to the hobby of roleplaying; it's also the only RPG that non-gamers know by name. D&D is thus the proverbial 800-lb. gorilla of roleplaying games. In a very real sense, the entirety of the hobby (and the industry supporting it) owes its very existence to D&D.

I don't think I'm being hyperbolic when I say this. Not only is it a historical fact that roleplaying games, as we know them today, are all ultimately descended from Dungeons & Dragons, but I contend that most of them would never even exist were it not for a phenomenon I'm going to call "D&D fatigue." As I'll explain, D&D fatigue takes two distinct forms and each of them plays a vital role in the continued existence of other RPGs – and perhaps of D&D itself.The first form of D&D fatigue comes is the more rarefied, experienced by those whose weariness with the game compels them to write their own game. For example, the second roleplaying game, Tunnels & Trolls , owes its existence to Ken St. Andre's dissatisfaction with Dungeons & Dragons, but neither St. Andre nor T&T are unique in this regard. Indeed, if you were to look at the history of RPGs, you'll quickly find many examples – many of them quite early – of people who felt that D&D was somehow lacking and resolved to improve upon it.

The second form of D&D fatigue is more common but no less important. This is a more literal type of fatigue, one experienced by those who've simply played D&D so much that they want to play something different. In my youth, my friends and I suffered many bouts of this kind of D&D fatigue. We'd play D&D furiously for weeks or months on end, enjoying ourselves all the while, and then, at some point, one of us would look up from our copy of the Players Handbook and ask, "Do you want to play something else?" Almost invariably, we did and thank goodness for that; otherwise, we might never have had the chance to play other great RPGs like Gamma World, Traveller, or Call of Cthulhu.

D&D fatigue is not a bad thing. As I stated at the beginning of this post, the existence of a larger roleplaying hobby depends, in large part, on people becoming dissatisfied with or tired of Dungeons & Dragons and creating and/or seeking out alternatives to it. Very few of those alternatives ever came close to rivaling D&D's popularity or sales – but they didn't have to. During the days of D&D's first faddishness, there were more than enough players to support many RPGs and the companies, large and small, that produced them. Simply by existing, D&D created a demand for alternatives that others stepped forward to fill.

Over the course of the more than four decades I've been roleplaying, I've fallen in and out of love with Dungeons & Dragons multiple times, for a variety of different reasons. In each case, I'd eventually return to playing it, because I do like D&D, warts and all. While I was feeling the full force of D&D fatigue, I'd explore other options, in the process learning to love other games I otherwise might not have noticed. I also learned to appreciate better the things I liked about D&D, so that, when I returned to playing it, I often had more fun with it than I did before.

As I said, D&D fatigue is not a bad thing.

August 24, 2022

The Sage Disagrees

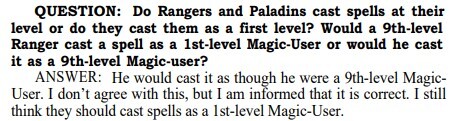

The "Sage Advice" column in issue #33 of Dragon (January 1980) contains the following question and answer:

The question itself is a genuinely interesting one, as I don't believe either the Players Handbook or Dungeon Masters Guide explicitly answers it (as always, please correct me in the comments if I am mistaken). More interesting, though, is the answer by the Sage (Jean Wells), where she states both the official rule and her own disagreement with it, along with her preferred interpretation. During her tenure as the Sage, Wells often expressed her own opinions, often drawing on her experiences playing Dungeons & Dragons. However, I can't recall any other time where she admitted to disagreeing with the official rules and then offering her alternative.

The question itself is a genuinely interesting one, as I don't believe either the Players Handbook or Dungeon Masters Guide explicitly answers it (as always, please correct me in the comments if I am mistaken). More interesting, though, is the answer by the Sage (Jean Wells), where she states both the official rule and her own disagreement with it, along with her preferred interpretation. During her tenure as the Sage, Wells often expressed her own opinions, often drawing on her experiences playing Dungeons & Dragons. However, I can't recall any other time where she admitted to disagreeing with the official rules and then offering her alternative.Simply from a historical perspective, this is remarkable. With the publication of the DMG in August 1979, AD&D is complete and that completion ushers in the era of wholly official answers to any question one might have about the rules. This is the Everything-I-say-is-God's-Holy-Word era, which makes it all the more striking that Wells would state her disagreement in such an unambiguous way. I suspect this might be because Wells began playing D&D quite early, in the wild and woolly age of "why have us do any more of your imagining for you?" Her job required her to state the official answer and so she did, but she was still very much a woman of the afterward [sic] to the 1974 rules.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers