Retrospective: Dragonlance Adventures

Although there are nearly four thousand posts on this blog, one of the most widely read remains "How Dragonlance Ruined Everything," published all the way back in 2008. Though the title is intentionally hyperbolic, I largely stand behind what I wrote then, namely that the release and success of the Dragonlance series of adventure modules was the crowning achievement of the Hickman Revolution and forever changed the trajectory of Dungeons & Dragons. I don't think this is disputable. Since 1984, D&D – and indeed roleplaying games in general – have been slowly evolving into a much more story-driven, character-focused form of entertainment than the by-blow of miniatures wargaming it was in 1974. Whether one views this evolution as good or bad is irrelevant to the truth of it.

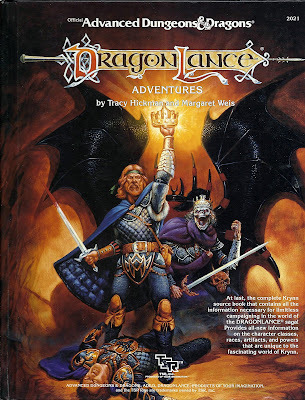

Although there are nearly four thousand posts on this blog, one of the most widely read remains "How Dragonlance Ruined Everything," published all the way back in 2008. Though the title is intentionally hyperbolic, I largely stand behind what I wrote then, namely that the release and success of the Dragonlance series of adventure modules was the crowning achievement of the Hickman Revolution and forever changed the trajectory of Dungeons & Dragons. I don't think this is disputable. Since 1984, D&D – and indeed roleplaying games in general – have been slowly evolving into a much more story-driven, character-focused form of entertainment than the by-blow of miniatures wargaming it was in 1974. Whether one views this evolution as good or bad is irrelevant to the truth of it.Consequently, it should come as no surprise that, as Dragonlance's star rose ever higher, TSR would attempt to use it as a platform to change the game mechanically as well as conceptually. Dragonlance Adventures demonstrates precisely what I mean. Published in 1987, DLA is a 128-page hardcover volume on the model of previous AD&D tomes like the Players Handbook. Though billed as a "source book," its content is not simply setting material; the book contains many new rules that augment or outright replace those of standard AD&D. In fact, many of these new rules, as we'll see, appear to be dry runs for rules that would later be incorporated into Second Edition when it appeared in 1989.

The most obvious changes in Dragonlance Adventures come in the form of its character classes. Almost every standard AD&D class is either altered or replaced in DLA, the only exceptions being fighter, barbarian, ranger, thief, and thief/acrobat. Consequently, the book provides quite a few new classes, such as three different types of clerics, wizards, and Knights of Solamnia, all of which tie closely into the history and cosmology of the world of Krynn. Also presented is the tinker class for use by the setting's unique take on gnomes. Other nonhuman races are similarly reimagined or, in the case of halflings, replaced entirely (which has the added benefit of severing some of D&D's most direct connections to Tolkien's Middle-earth – there are no orcs on Krynn, for example).

Though these changes, as I note, are presented in order to bring the rules more into line with the realities of the setting, they also enable Tracy Hickman, who is credited as the book's "designer," to tinker with some of AD&D's rules in ways that, at the time, were genuinely original. For example, the three types of wizards – White, Red, and Black – are distinguished not simply by their alignment, but also by which "spheres" of magic to which they have access. These spheres are simply AD&D's schools of magic (abjuration, conjuration, etc.) renamed. The effect of this change is to differentiate wizards by their background and training, much in the way that Second Edition would do with specialist wizards. Similarly, clerics would have access to different spheres of spells based on the interests of the gods they served.

The mechanical treatment of Krynn's races is quite similar, fiddling as it does with the verities laid down in the Players Handbook. Not only does Hickman shift the ability score ranges, he alters both the availability of classes and, more significantly, their level limits. Silvanesti Elves, for instance, can be paladins and they're unlimited in their advancement, two remarkable deviations from the Gygaxian canon of earlier AD&D. There are also rules for playing minotaurs, who, while brutal, are not inherently evil or unintelligent – another notable shift away from the "facts" of the game as it was known at the time.

From the vantage point of present day D&D, filled as it is with innumerable new character classes, nonhuman species, and nary a level limit to be seen, none of this likely appears worthy of mention, let alone suspicion. Yet, at the time, these tentative steps away from the humanocentric, pulp fantasy picaresque of Golden Age D&D were truly revolutionary, especially coming from TSR, which had previously resisted – and, under Gygax, mocked – any such attempts to upend the game's presentation and focus. A great many people, myself included, welcomed these changes and felt that they presaged a a great sea change in the game. As it turned out, we were more prescient than we realized and Dragonlance Adventures served as the herald of the new age aborning, just as the Dragonlance adventure modules had done several years previously.

There's a lot more that could be said about this book and the role it played in changing the design of AD&D, such as its inclusion of the non-weapon proficiencies of the Dungeoneer's and Wilderness Survival Guides as baseline features of the rules. While I don't want to minimize the significance of their inclusion, even more significant, I think, is the overall presentation of DLA, which offers the reader – more on that in a moment – a coherent setting whose rules are designed to emulate and reinforce its flavor and themes. Krynn is explicitly a setting that "promot[es] the power of truth over injustice, good over evil, and grant[s] good consequences for good acts and bad consequences for evil acts." The Angry Mothers from Heck would be pleased.

Let me conclude with a brief note about the book's preface, which states that "you can certainly enjoy this book without playing the game." Though Hickman and Weis quickly enjoin the reader to play, I think it's significant that the preface even countenances the idea that one might buy Dragonlance Adventures without wishing to play AD&D. We must remember how popular – and lucrative – the Dragonlance novels were and how many people became fans of the setting and its characters as a result. I'd wager that, while Dragonlance was very profitable for TSR, the number of new players it introduced to playing D&D was not nearly as great. Dragonlance (and, by extension, D&D) was a powerful brand and that's all that mattered. Once again, Dragonlance was a forerunner of what was to come.

Published on August 31, 2022 09:00

No comments have been added yet.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers

James Maliszewski isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.