James Maliszewski's Blog, page 104

August 2, 2022

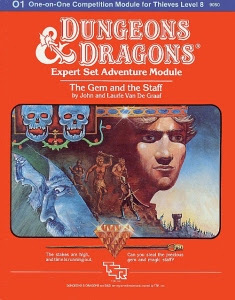

Retrospective: The Gem and the Staff

An aspect of the Little Brown Books of OD&D that's often commented upon is the statement, early on in Volume 1, that a single campaign consists of "from four to fifty players." By contemporary standards, that's quite a large number of players. In truth, it was quite large even in my own youth, though it wasn't at all uncommon to encounter RPG groups of a dozen or more. I can't speak to how common that was, outside of organized game clubs, but I get the impression that, in the first few years of the hobby, there was an expectation that a "typical" adventuring party consisted of six to twelve characters.

An aspect of the Little Brown Books of OD&D that's often commented upon is the statement, early on in Volume 1, that a single campaign consists of "from four to fifty players." By contemporary standards, that's quite a large number of players. In truth, it was quite large even in my own youth, though it wasn't at all uncommon to encounter RPG groups of a dozen or more. I can't speak to how common that was, outside of organized game clubs, but I get the impression that, in the first few years of the hobby, there was an expectation that a "typical" adventuring party consisted of six to twelve characters.At some point, though, that expectation started to change. I can't pinpoint precisely when the shift occurred, but it's clear that it did so. By the 1990s, if not before, I started to notice that gaming groups (and, by extension, adventuring parties) were getting smaller and smaller, with three or four characters being much more typical. I have lots of unsubstantiated theories about why this shift might have occurred. Regardless of the reason, I contend that gaming groups in the second decade of the hobby were smaller than those in the first decade.

Circumstantial evidence in support of my thesis is the fact that, throughout the 1980s, TSR experimented with multiple formats to facilitate the playing of solo and one-on-one Dungeons & Dragons. There were modules like Blizzard Pass and Midnight on Dagger Alley, not to mention the D&D-branded Endless Quest books, which, while not as genuinely game-like as, say, the Fighting Fantasy series, were nevertheless an attempt to present a solo D&D "experience." Another approach was the one adopted by 1984's The Gem and the Staff by John and Laurie Van De Graaf. Written for a single player and a Dungeon Master, module O1 is the only example of this kind of module from TSR. I assume, based on the fact that there were never any similar modules, it was not as well received as the company might have hoped.

Like TSR's previous solo efforts, The Gem and the Staff comes with a pregenerated character, Eric the Bold. Also like TSR's previous efforts, Eric belongs to a class with thief abilities (in this case, being an actual thief). I find it fascinating that every TSR module in this general class of adventures relies on the player character being a thief or thief-like class. I'm certain this is because thief abilities provide an obvious way to handle non-combat actions. Indeed, all these modules are structured in a way that's reminiscent of the 1980 video game, Rogue, which has proven extremely influential in the decades since.

In the case of The Gem and the Staff, the module consists of two distinct scenarios, "Tormaq's Tower" and "The Staff of Fazzlewood." In each, Eric is expected to steal a valuable item in the possession of the wizard Tormaq. To succeed, the player must use stealth and quick wits to overcome not just traps (both mundane and magical) but also monsters and other opponents (such as Tormaq himself). To aid in visualizing the various rooms Eric must navigate, the module includes a map book for players that's somewhat akin to the cardboard dungeon floors I occasionally used as a kid. Also included are little cut-out figures to mark the locations of Eric and his potential opponents. This is a nice little feature in my opinion and it certainly helps both the player and referee to get a good handle on Eric's progress.

As presented, the idea behind The Gem and the Staff is that, after the completion of the first adventure, the player and referee swap places with one another. I'll admit that it's an odd conceit and I have no idea how many people who bought the module ever followed its instructions in this regard. Of course, because of its set-up – a single pregenerated character of 8th level and very limited scopes for the two scenarios – I have to wonder how many people ever made use of it at all. I certainly never did, though I repurposed the player's maps for something else entirely.

I'm not really sure what to make of The Gem and the Staff. The module has its origins in a tournament event from the late 1970s, which may explain its "boxed in" feel, not to mention the slightly "adversarial" nature of its one-on-one presentation. The result is something that's a lot more explicitly "game-y" than many D&D modules, more like a puzzle that needs to be solved than an exercise in roleplaying as I typically understand it. In that respect, my earlier reference to the video game Rogue is not far from the mark, though The Gem and the Staff predates it (in its original form, prior to TSR's publication of it). In the end, I suspect this is simply another failed experiment from a period seemed to be throwing lots of ideas against the wall to see what might stick.

An Experiment

The people of Inba Iro burn their dead, believing the soul can only return to the eternal gods if so liberated from the prison of the flesh. For this reason, the priests of Jilho the Protector deny condemned lawbreakers cremation. Through sorcery, they instead compel them to serve after execution as guardians of the upper levels of the Vaults. Only fire can permanently end a dritlor's earthly bondage or else it reanimates not long after its apparent destruction.

STR 2d6+6 (13), CON 1d6 (4), DEX 3d6 (11), SIZ 3d6 (11), INT 0, POW 0, CHA 0, HP 8, DM 0, MP 0, MR 15, Armor Leather (2), Treasure 0, Dodge 10%, Persistence 100%, Resilience 100%, Close Combat 35%: Longspear (1d8), Medium Shield (1d6)

Guardians: Always attacks on sightUndead: Immune to all diseases, fatigue, poisons, and mind control.Reanimation: If destroyed (0hp), stitches itself back together to full hp and fights again after 2d6 rounds.Fire: Cannot reanimate if burned after destruction. A dritlor by Zhu Bajiee

A dritlor by Zhu Bajiee

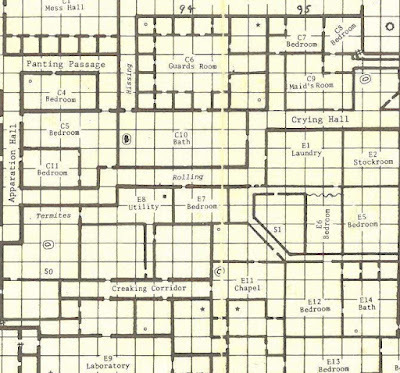

Mapmaking as a Game within a Game

When I first heard about Dungeons & Dragons, an aspect of the game that both fascinated and confused me was that it didn't have a board, unlike any other game with which I had experience up to that point. The lack of a board was something I remember reading in the many newspaper accounts of the game I saw during the late Summer and Fall of 1979. How could it be a game without a board? Furthermore, many of the media accounts of the game also talked about how the players made use of sculpted miniature figures to play. Figures? But no board? What was going on?

When I first heard about Dungeons & Dragons, an aspect of the game that both fascinated and confused me was that it didn't have a board, unlike any other game with which I had experience up to that point. The lack of a board was something I remember reading in the many newspaper accounts of the game I saw during the late Summer and Fall of 1979. How could it be a game without a board? Furthermore, many of the media accounts of the game also talked about how the players made use of sculpted miniature figures to play. Figures? But no board? What was going on? My confusion only increased after my encounter with Dungeon! over the Christmas break of that same year. Dungeon! most certainly did have a board and it certainly seemed quite similar to D&D, though it didn't make use of any sculpted figurines. In time, I made more sense of it all, thanks in part to various gaming mentors, who showed my friends and I the "right" way to play D&D, including the fact that the game's "board" was a hand-drawn map that a player drew as his party of adventurers explored a dungeon. This lesson from my elders was potent and, to this day, I continue to associate D&D strongly with maps and, more importantly, mapmaking.

Mapmaking is an aspect of D&D that, so far as I can tell, has largely disappeared or at least has been downplayed over the years. In the present moment, one might even say that it's been superseded by technology like virtual tabletops that obviate the need for graph paper and pencil. Nevertheless, maps themselves remain an important part of gameplay. Nearly every adventure, whether prepackaged or homebrewed, includes a map of its most important locales and, in many of them, exploring that map is a central feature of gaming sessions.

From my extremely anecdotal survey of the situation, I have the impression that many gamers today don't really miss the days of making their own maps. Some have even admitted that they never really enjoyed mapmaking, which they found, by turns, tedious, frustrating, and generally unpleasant. I completely understand this point of view, especially when you consider the kinds of dungeon maps that frequently appeared during the first decade of the hobby. They're filled with mazes, one-way and secret doors, teleportation traps, shifting and sliding walls, dead end corridors, and similar annoyances, all of which are specifically intended to foil or at least hinder accurate mapmaking. Where's the fun in that?

The question is more than fair in my opinion and I don't begrudge anyone who has limited or no tolerance for the vicissitudes of mapmaking – or the labyrinthine dungeons that necessitated them. At the same time, I think it's a mistake to think manual mapmaking has simply been supplanted by virtual tabletops and the like. It's increasingly my feeling that mapmaking – by hand, based on the referee's verbal descriptions – is a key activity of the game, since D&D is as much a game of exploration as it is of, say, combat. I'd also argue that it's a game with a strong element of puzzle solving and tricky dungeon maps play a big part in facilitating that element of the game.

None of this is to suggest that D&D can only be played with manual mapmaking, only that something is lost when it's not included. That's why certain races, character classes, spells, and magic items have or grant abilities that pertain to exploring the physical environment of a dungeon – finding secret doors, sloping passages, etc. It thus seems pretty clear to me that, at least as envisioned by Gary Gygax (and probably Dave Arneson as well), the play of Dungeons & Dragons revolved around, at least in part, "solving" the puzzle of a dungeon's layout, much in the same way that players did in early computer games like Wizardry or Telengard.

I don't know. I'm still trying to figure this out for myself. It may well be that manual mapmaking is simply a transitional technology that isn't nearly as integral to the way its creators intended D&D to be played as I'm suggesting here. Nevertheless, I can't shake the feeling that there's more going on than we realize and that the large scale abandonment of fumbling around with pencil and graph paper is another step on the road to a fundamental shift in the way Dungeons & Dragons is conceived and played.

New Directions for a Proven Leader

Here's an unusual TSR advertisement that started appearing during the summer of 1983.

I've long called science fiction an "also ran" genre in the hobby of roleplaying games, because, with the exception of Traveller in its heyday (and West End's Star Wars some time later), SF RPGs rarely captured a significant share of players. That's why it's interesting to see TSR trying to promote its various science fiction properties, like Star Frontiers and

Gamma World

, not to mention the recently acquired Ares magazine, as part of the company's "new directions."

I've long called science fiction an "also ran" genre in the hobby of roleplaying games, because, with the exception of Traveller in its heyday (and West End's Star Wars some time later), SF RPGs rarely captured a significant share of players. That's why it's interesting to see TSR trying to promote its various science fiction properties, like Star Frontiers and

Gamma World

, not to mention the recently acquired Ares magazine, as part of the company's "new directions." I can't help but wonder if ads like this suggest that TSR is simply doing so well that it feels confident enough of its position in the market to expand seriously into SF or rather that doing so had become a necessity as D&D's sales were slowing. I assume the former, but I have no special insights into the matter. Regardless, being a SF fan at heart, I appreciate seeing advertising like this (even if I wonder why TSR included the original 1978 version of Gamma World rather than the new one released the same year).

August 1, 2022

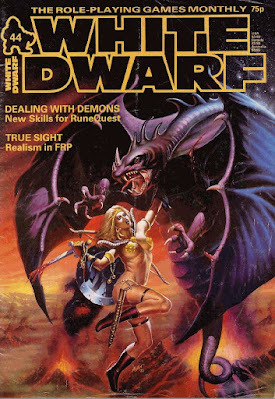

White Dwarf: Issue #44

Though I was – and remain – a big fan of Daniel Collerton's "Irilian" series of articles, the first two installments of which appeared in the previous two issues, issue #43 of White Dwarf (August 1983) isn't one for which I'd had any strong memories. You'd think I'd have remembered the cover by Jim Burns, if nothing else, since it's quite unlike what I consider a "typical" WD cover. That might be because the magazine was still in the midst of its "new look," the last phase of which would be implemented in issue #44, according to editor Ian Livingstone. In any case, re-reading this issue almost felt like I was reading it for the first time, even though I know I owned a copy in my youth.

Though I was – and remain – a big fan of Daniel Collerton's "Irilian" series of articles, the first two installments of which appeared in the previous two issues, issue #43 of White Dwarf (August 1983) isn't one for which I'd had any strong memories. You'd think I'd have remembered the cover by Jim Burns, if nothing else, since it's quite unlike what I consider a "typical" WD cover. That might be because the magazine was still in the midst of its "new look," the last phase of which would be implemented in issue #44, according to editor Ian Livingstone. In any case, re-reading this issue almost felt like I was reading it for the first time, even though I know I owned a copy in my youth."On ICE" by Marcus L. Rowland is a Traveller article that focuses on Interstellar Charter Enterprises (ICE), a business that rents starships – and starship crews – to those who lack them. Of course, ICE offers other services as well, those of a criminal variety, such as outfitting their rented vessels with equipment and modifications for engaging in smuggling, piracy, etc. The article details not just ICE itself but also the kinds of scenarios in which they might be involved. Rowland even provides three sample patron encounters as examples of how the organization might be used in a campaign.

"Open Box" reviews Shadows of Yog-Sothoth for Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu, to which it gives its highest rating (10 out of 10). Despite its shortcomings, I think that's more than fair, especially in 1983, since it was the only example of a complete, prewritten CoC campaign available at the time (and it is quite good). Meanwhile, Illuminati Expansion Sets 1 and 2 both receive 6 out of 10. I don't believe I ever owned or played these expansions, so it's hard for me to judge the fairness of these ratings. On the other hand, I owned all four of the AD&D modules reviewed: The Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth (9 out of 10), The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun (9 out of 10), Against the Cult of the Reptile God (8 out of 10), and Danger at Dunwater (8 out of 10). The two Gygax modules are true classics and among my favorites; the other two are also quite creditable, though I'd probably have given them both 7 out of 10, but that's a quibble. Finally, there are reviews of two Endless Quest books – Revolt of the Dwarves and Revenge of the Rainbow Dragons – both of which garner 5 out of 10.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" begins his column complaining about the lack of contemporary British science fiction and fantasy authors in a UK book marketing campaign, which, I suppose, is fair, though it doesn't hold much interest almost forty years on. Much more interesting is his praise of Gene Wolfe's Book of the New Sun. Langford has a few small criticisms – he wouldn't be Dave Langford if he didn't – but, by and large, he recommends the series highly. He even uses its excellence to get in another dig at Stephen R. Donaldson (one of his favorite sports, as I recall).

"True Sight" by Lewis Pulsipher is a short column discussing "realism in D&D and other fantasy role-playing games." This topic was no doubt a tired one even in 1983 and certainly is so now. However, Pulsipher manages to make it more interesting by noting that the kind of realism that interests him is believability. To that end, he focuses on three areas: familiarity, self-consistency, and completeness. It's an unusual approach but, in the course of the article, he manages to raise some good questions for any referee to consider. I still wonder why the article references "realism" in its subtitle, since the article doesn't spend much time on that topic as it's usually understood in gaming circles (perhaps Pulsipher had nothing to do with the subtitle?).

"Counterpoint" is a new column devoted to boardgames. Its inaugural article, by Charles Vasey, spends most of its single page on extended discussions of two games: Sanctuary from Mayfair Games (based on the Thieves' World anthology series) and Sherlock Holmes, Consulting Detective. Vasey likes both games a great and he spends some of the column musing on the similarities between the RPG Call of Cthulhu and the Holmes game. It's an angle I hadn't considered before, but it makes sense after a fashion.

"Dealing with Demons" by Dave Morris is the first part of a series dealing with demon summoning in RuneQuest. The first part presents rules for magical protections, binding, and pacts, not to mention curses and possession. It's rather remarkable article, full of good ideas for incorporating demonology into RQ for those so inclined. Accompanying it is a comic strip that imparts some genuine information about the process of summoning demons, in addition to being funny. I remember the second and third parts of this article quite well, so it was good to have the chance to re-familiarize myself with the first one.

The computer column, "Microview," looks at combat resolution computer programs for both Tunnels & Trolls and AD&D. The former is given a completed program by D.G. Evans, while the latter gets only an overview (by Noel Williams) of what one would need to consider before making such a program for use with Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. Articles like this are of interest only as historical artifacts and this one is no exception. Part three of Daniel Collerton's "Irilian," however, continues to delight. This issue's installment offers information on another quarter of the town and its businesses and inhabitants. This one is noteworthy for including details on certain guilds – or "gilds" in the Old English it uses for naming – like the guild of beggars.

"Rune Rites" presents two new monsters for use with RuneQuest, most notably the golem (and the necessary spell create golem). The theme of this month's "Fiend Factory" is "Tribes and Tribulations," meaning intelligent monsters that organize themselves into tribes. None of them are particularly notable, I'm sorry to say, and the less said about the "Blacklings," halfling counterparts to the drow, the better. Graeme Davis's "Seeing the Light" is much more intriguing. It's a simple system for handling religious conversion of monsters and NPCs by clerics. There's also another "Gobbledigook" comic strip.

Issue #44 continues to demonstrate that White Dwarf is really hitting its stride at this time. The selection and quality of its articles continues to be solid, with several of them being worthy of examination even today. I'll admit to finding it odd that there's not a single Call of Cthulhu article in this issue, but I have little doubt that's only a temporary absence. As I've no doubt written several times previously, I associate White Dwarf most strongly with four RPGs: AD&D, Traveller, Call of Cthulhu, and RuneQuest (all of which, to varying degrees, I can see as influences upon Games Workshop's later Warhammer Fantasy Role Play). Since the first three are in my pantheon of the favorite roleplaying games of my youth (and the fourth has subsequently been added), it's little wonder why I continue to enjoy these weekly re-reads.

Speaking of Burn, Witch, Burn!

As some of you may recall, I was asked by Centipede Press to write the introduction to a new edition of Abraham Merritt's Burn, Witch, Burn! The book was recently released in a limited print run and almost immediately sold out, which is unfortunate, because it's a lovely piece of work that I'd have been proud to have on my bookshelf, even if I hadn't been involved in its creation.

Here's the cover and spine of the book. Not visible is the silk bookmark.

This is the table of contents, featuring some of the terrific, original artwork by Dan Rempel.

This is the table of contents, featuring some of the terrific, original artwork by Dan Rempel.

Of course, no edition of a work by Merritt would be complete without illustrations by Virgil Finlay, an artist from whom Merritt commissioned more than a thousand pieces during his lifetime.

Of course, no edition of a work by Merritt would be complete without illustrations by Virgil Finlay, an artist from whom Merritt commissioned more than a thousand pieces during his lifetime.

Though the limited edition of the book is sold out, Centipede Press is planning to produce a reprint in the future. When it's available for sale, I'll make an announcement here, since I think it would definitely be of interest to many readers.

Though the limited edition of the book is sold out, Centipede Press is planning to produce a reprint in the future. When it's available for sale, I'll make an announcement here, since I think it would definitely be of interest to many readers.

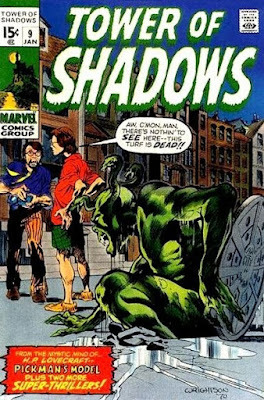

Marvel and HPL

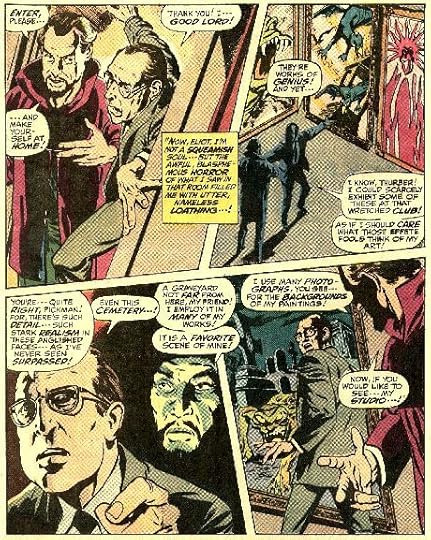

A largely faithful adaptation of Lovecraft's "Pickman's Model" was found in the pages of issue #9 (January 1971) of Marvel's Tower of Shadows comic. Tower of Shadows was a horror anthology book that Marvel published between 1969 and 1971, after which it was revamped and its title changed to Creatures on the Loose! (which lasted until 1975). Each issue of the comic typically featured three or four stories, some original and some adapted from the works of other authors.

A largely faithful adaptation of Lovecraft's "Pickman's Model" was found in the pages of issue #9 (January 1971) of Marvel's Tower of Shadows comic. Tower of Shadows was a horror anthology book that Marvel published between 1969 and 1971, after which it was revamped and its title changed to Creatures on the Loose! (which lasted until 1975). Each issue of the comic typically featured three or four stories, some original and some adapted from the works of other authors.Roy Thomas of Conan the Barbarian fame adapted "Pickman's Model," with Tim Palmer (of Tomb of Dracula) providing the artwork. As I said, it's quite faithful to Lovecraft's original tale. The same characters are present (with the same names) and the plot proceeds more or less identically to the short story on which it's based. There are only two differences that I can detect.

The first difference is the least consequential. Rather than being set in the 1920s, it's set in the early 1970s – the present day of the comic. That has few, if any, repercussions for the story itself beyond esthetic ones. The second is the appearance of the creature that Pickman paints. You can see what it looks like on the cover illustration above. Lovecraft had described the creature as vaguely "canine" in appearance; the creature in the comic is nothing like that. Whether that matters greatly is a matter of taste, I suppose, though I personally prefer the traditional appearance of Pickman's model, particularly in light of Pickman's subequent reappearance in The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath.

For those interested in such things, here are a couple of representative pages from the adaptation.

As you can see, Pickman looks like he might have been modeled on Vincent Price (or perhaps Doctor Strange). Here's the concluding panel to the comic, in which the photograph of the model is shown:

As you can see, Pickman looks like he might have been modeled on Vincent Price (or perhaps Doctor Strange). Here's the concluding panel to the comic, in which the photograph of the model is shown:

I'm still not sure why Thomas and Palmer chose to depict the model in this fashion. It's certainly a memorable monster, but it's not a particularly Lovecraftian one. All in all, this is mostly a purist quibble about an otherwise close adaptation of a classic HPL tale.

I'm still not sure why Thomas and Palmer chose to depict the model in this fashion. It's certainly a memorable monster, but it's not a particularly Lovecraftian one. All in all, this is mostly a purist quibble about an otherwise close adaptation of a classic HPL tale.

Rod Serling and HPL

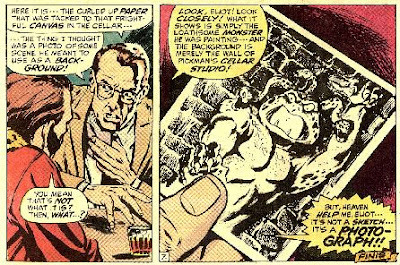

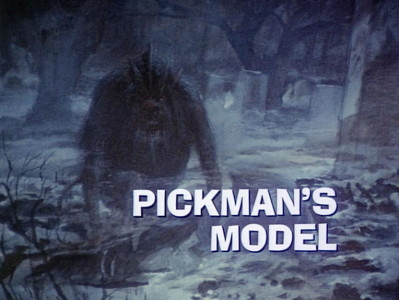

Last month, I mentioned that Clark Ashton Smith's "The Return of the Sorcerer" had been adapted for Rod Serling's Night Gallery television series in 1972. As some of you likely already know, that wasn't the only time that a story by one the greats of Weird Tales appeared on the program. At the end of the previous year – December 1, 1971, to be exact – there was an adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft's "Pickman's Model."

Like the adaptation of "The Return of the Sorcerer," this one isn't a particularly faithful to its literary forebear. For one, the episode introduces the framing device of a man in the 1970s who's bought an old home in Boston that was once owned by the 19th century artist, Richard Upton Pickman. Pickman, we're told, disappeared mysteriously seventy-five years prior and most of his macabre artwork was lost along with him. The new owner of the place discovers some canvases hidden in the building that he assumes must have belonged to Pickman, including the one featured above. His friend is the owner of an art gallery and assures him that, were these paintings to truly be those of Pickman, they'd be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Like the adaptation of "The Return of the Sorcerer," this one isn't a particularly faithful to its literary forebear. For one, the episode introduces the framing device of a man in the 1970s who's bought an old home in Boston that was once owned by the 19th century artist, Richard Upton Pickman. Pickman, we're told, disappeared mysteriously seventy-five years prior and most of his macabre artwork was lost along with him. The new owner of the place discovers some canvases hidden in the building that he assumes must have belonged to Pickman, including the one featured above. His friend is the owner of an art gallery and assures him that, were these paintings to truly be those of Pickman, they'd be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. We then flashback to the end of the previous century, where Pickman is giving art lessons to young women of well to do families, one of whom takes a romantic interest in him. Though he begs her to leave him be and not try to get too close to him, she persists, eventually following him to his home in the North End of the city.

Once there, Pickman again tries to convince her to leave, but she will not, eventually encountering the model he'd been using for some of his most horrific paintings.

Once there, Pickman again tries to convince her to leave, but she will not, eventually encountering the model he'd been using for some of his most horrific paintings.

The episode isn't awful and, much like the adaptation of "The Return of the Sorcerer," it doesn't lack charm in certain respects. The tale as presented on screen is a lot more melodramatic than Lovecraft's own take on it and the framing device is a bit silly, especially at the end, when it's shown that the monster – it's never called a ghoul or indeed anything – still exists in the tunnels beneath Pickman's old home and lies waiting for the chance to be loosed upon the world once more.

The episode isn't awful and, much like the adaptation of "The Return of the Sorcerer," it doesn't lack charm in certain respects. The tale as presented on screen is a lot more melodramatic than Lovecraft's own take on it and the framing device is a bit silly, especially at the end, when it's shown that the monster – it's never called a ghoul or indeed anything – still exists in the tunnels beneath Pickman's old home and lies waiting for the chance to be loosed upon the world once more.If you're interested in watching the episode, it can be found on the Internet Archive site, at least for the moment. It's short and, despite its flaws, worth the twenty-two minutes or so it'd take to see it in its entirety.

July 31, 2022

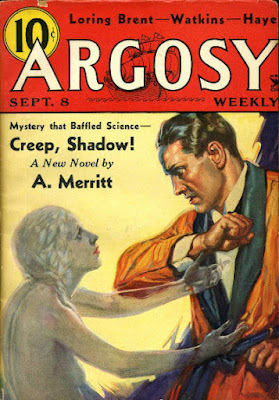

Pulp Fantasy Library: Creep, Shadow!

Of the authors listed in Gary Gygax's Appendix N, one of the most obscure to contemporary readers is no doubt Abraham Grace Merritt (or A. Merritt, as he was known during his lifetime). That's why, more than a decade ago, I dubbed him a "forgotten father" of fantasy, science fiction, and horror. Much like his contemporary, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Merritt has exerted a huge, though frequently unacknowledged, influence on much of the popular fiction that came after him (and the popular culture that it, in turn, inspired).

Of the authors listed in Gary Gygax's Appendix N, one of the most obscure to contemporary readers is no doubt Abraham Grace Merritt (or A. Merritt, as he was known during his lifetime). That's why, more than a decade ago, I dubbed him a "forgotten father" of fantasy, science fiction, and horror. Much like his contemporary, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Merritt has exerted a huge, though frequently unacknowledged, influence on much of the popular fiction that came after him (and the popular culture that it, in turn, inspired). Gary Gygax was quite consistent in his praise for Merritt's works, placing them on par with those of other more well known authors. In the Dungeon Masters Guide, for instance, he states that Merritt is one of "the most immediate influences upon AD&D," alongside such greats as Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, Jack Vance, and H.P. Lovecraft, all of whom, I'd wager, enjoy much higher profiles in the 21st century. In Appendix N, Gygax singles out three of Merritt's stories for particular mention: The Moon Pool, Dwellers in the Mirage, and Creep, Shadow, Creep. Though I've listed Creep Shadow! last (and under its later title, as Gygax did), it is, in fact, the first of Merritt's titles in Appendix N and for good reason, as I hope to explain.

Like many of Merritt's tales, Creep, Shadow! was serialized in the pages of a weekly periodical, in this case The Argosy, the premier pulp magazine of the early 20th century. Creep, Shadow! appeared in seven consecutive issues between September 8, 1934 and October 20, 1934. The following year, the serial was collected into a single volume and released as a stand-alone novel, under the title of Creep, Shadow, Creep!, which is how many later readers, including Gary Gygax, would come to know it. So far as I know, there are no significant differences between the two versions of the story, other than their titles. In the decades since its original publication, the story has appeared under both titles.

Creep, Shadow! is a sequel of sorts to Merritt's earlier tale, Burn, Witch, Burn! (which might explain why the title was later changed). I say "of sorts" because, while Dr. Lowell reappears, he is a supporting character rather than the protagonist. Instead, the story focuses on a different man of science, in this case Dr. Alan Caranac, an ethnologist, who, like Dr. Lowell, is interested in "those fields which [his] medical and allied scientific brethren call superstition—native sorceries, witchcraft, voodoo, and the like." Caranac travels widely across the globe in the course of his work, so much so that he tells the reader that his colleagues attribute

my wanderings to an itching foot inherited from one of my old Breton forebears, a pirate who had sailed out of St. Malo and carved himself a gory reputation in the New World. And ultimately was hanged for it. The peculiar bent of my mind he likewise attributed to the fact that two of my ancestors had been burned as witches in Brittany.

Regular readers of Merritt will almost certainly know that comments like this are included not just for color, but because they have relevance to the story.

All that aside, the action of the novel begins with an investigation into a series of mysterious deaths. In this case, the deaths are in fact suicides and the suicides of wealthy and influential men at that. One of these men is Richard "Dick" Ralston, a friend of Caranac, who had inherited $5,000,000 two years prior, following the death of his own father, a copper magnate. More ominously, Ralston's suicide note mentions Caranac: "If only Alan were here. He knows more–"

The suicide note is addressed to Dr. Bill Bennett, a brain surgeon and mutual friend of both Ralston and Caranac (and Dr. Lowell of Burn, Witch, Burn! we also learn). Unsurprisingly, Bennett comes to see Caranac. He implies that, as Caranac himself suspects, there's more to this story than the police realize.

"What do you know that the police don't know, Bill?"

He said: "That Dick was murdered!"

I looked at him, bewildered. "But if he put the bullet through his own brain—"

He said: "I don't blame you for being puzzled. Nevertheless—I know Dick Ralston killed himself, and yet I know just as certainly that he was murdered."

Later, detectives call upon Caranac, along with reporters, all of whom are eager to discover what he might know about Bennett's suicide or why his name was mentioned in his suicide note. During the course of his interview with a reporter, Caranac talked about his travels and the superstitions of the various places he'd visited. One of them concerned the belief that measuring a man's shadow with a string and then burying the string in a box would result in his death. The reporter liked this superstition enough to mention it in his article about Caranac, much to the consternation of Bennett.

"What put it in your head to talk to that reporter about shadows?"

He sounded jumpy. I said, surprised:

"Nothing. Why shouldn't I have talked to him about shadows?"

He didn't answer for a moment. Then he asked:

"Nothing happened to direct your mind to that subject? Nobody suggested it?"

"You're getting curiouser and curiouser, as Alice puts it. But no, Bill, I brought the matter up all by myself. And no shadow fell upon me whispering in my ear—"

He interrupted, harshly: "Don't talk like that!"

Bennett asks Caranac to join him at the home of Dr. Lowell for a party. There he hopes to discuss his latest thoughts about Ralston's suicide – or murder. One of Lowell's guests is a famed French psychiatrist named De Keradel and his daughter, Dahut. De Keradel is an expert in hypnosis and holds some unusual notions regarding the transmigration of souls. About De Keradel, Caranac says:

I began to feel a strong interest in this Dr. de Keradel. The name was Breton, like my own, and as unusual. Another recollection flitted through my mind. There was a reference to the de Keradels in the chronicles of the de Carnacs, as we were once named. I looked it up. There had been no love lost between the two families, to put it mildly. Altogether, what I read blew my desire to meet Dr. de Keradel up to fever point.

Even those who have not read any of Merritt's other works will discern where the story is going, especially in light of Caranac's earlier comments about his ancestry. Past lives and ancestral memory play major roles in several of Merritt's works and Creep, Shadow! is no exception. De Keradel repeatedly suggests that, through the medium of ancestral memory, passed down from generation to generation, one might gain access to ancient wisdom that would otherwise have been lost. Indeed, he implies, as does his daughter, that this wisdom might grant one mastery over powers no man has seen in centuries.

It's a given that all these various threads – Ralston's death, shadows, atavisms, ancient wisdom – eventually come together. It's similarly a given that Merritt weaves them all into a single tale with remarkable verve. Though written nearly a century ago, Creep, Shadow! nevertheless manages to capture the imagination and hold one's attention. In particular, the elements of past lives, ancestral memory, and the transmigration of souls are used compellingly. Also noteworthy are the titular shadows, which so left an impression on Gary Gygax that he not only included a monster inspired by it in OD&D but wished to explore the concept of Shadowland itself. If you've ever wondered why the original presentation of the shadow in Dungeons & Dragons was not an undead being, look no further than this novel.

There's a great deal going on in Creep, Shadow! and I don't feel I've done it sufficient justice in even this somewhat long post. This is Merritt at the height of his powers, elaborating on the themes that have filled his stories since the start of his fiction writing career. His characters are compelling and his descriptions vivid. Most importantly, he presents an engaging mystery filled with terrific twists and turns (and not a few genuine frights). To call Creep, Shadow! Merritt's masterpiece might be a slight exaggeration, but it is nevertheless one of his greatest works and well worth one's time.

July 26, 2022

White Dwarf: Issue #43

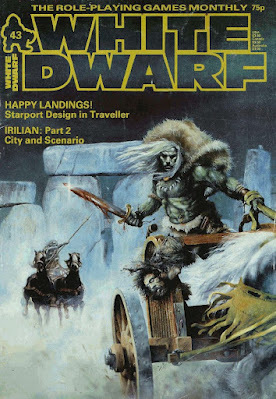

With issue #43 of White Dwarf (July 1983), we are well within the range of issues I remember strongly from my youth. This is the period before I'd actually subscribed to the magazine – that would come a little while later – but after I'd made it a point to pick up a new issue each month. Consequently, I still have a vivid recollection of this Jim Burns cover. Strangely, I also recall Ian Livingstone's editorial in which he suggests that computer games can never replace tabletop RPGs (or even boardgames) for the satisfaction they provide in playing them with (or against) human beings. Nearly forty years later, I find it hard to disagree.

With issue #43 of White Dwarf (July 1983), we are well within the range of issues I remember strongly from my youth. This is the period before I'd actually subscribed to the magazine – that would come a little while later – but after I'd made it a point to pick up a new issue each month. Consequently, I still have a vivid recollection of this Jim Burns cover. Strangely, I also recall Ian Livingstone's editorial in which he suggests that computer games can never replace tabletop RPGs (or even boardgames) for the satisfaction they provide in playing them with (or against) human beings. Nearly forty years later, I find it hard to disagree.

Part 2 of Marcus L. Rowland's "Cthulhu Now!" presents two mini-scenarios and one campaign outline for use in a Call of Cthulhu campaign set in the 1980s. One of these, entitled "Trail of the Loathsome Slime," would become the basis for a licensed CoC adventure published by Games Workshop at a later date. Since I never owned that particular book, I can't say how closely it hews to Rowland's original idea. I really enjoyed this article back in 1983 and it encouraged me to try my hand at modern day Call of Cthulhu.

"Open Box" reviews Warhammer in its initial release, earning 8 out of 10. I've mentioned before that I've never had the chance to look at this version of the game and now I wish I had. It's a pity that it's nigh impossible to find a copy at a reasonable price. Oliver Dickinson gives Questworld, Chaosium's alternate setting for RuneQuest, a mere 6 out of 10, which surprises me, as my (admittedly hazy) recollection is that it was more interesting than that. I shall have to re-read it sometime soon to see if I agree with Dickinson's assessment. Finally, there's a review of the play-by-mail game, The Tribes of Crane, which garners a 9 out of 10 – high praise indeed! I never got into play-by-mail games, but I'm fascinated by them, so such a positive review only piques my interest further.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" looks at a number of books, starting with a couple casting skeptical eyes on psychic and related phenomena. He follows it up with reviews of Alfred Bester's The Deceivers and The Insider by Christopher Evan. I've read the former, but I've never even heard of the latter. Go figure. "Hanufa's Little Sister" is Oliver Dickinson's final short story of Griselda. The tale includes a note that information on her further exploits can be found in Chaosium's Pavis. This is true: the boxed set released the same year as this issue includes another short story of Griselda, also written by Dickinson (though her game stats appear in Big Rubble, along with those of her associates).

"Magimart" by Lewis Pulsipher briefly discusses the ups and downs allowing the buying and selling of magic items in a D&D campaign. As with so many of Pulsipher's articles, he offers sound advice, though it's difficult, from the vantage point of the present, to appreciate it fully, since so much of what he has to say has since passed into the collective wisdom of the hobby. "Vehicle Combat" by Andy Slack, meanwhile, remains of lasting interest. It's a nice, simple system for adjudicating vehicle combat in Traveller without recourse to Striker (though it does make use of Mercenary). I had a lot of fun, thanks to this article, so it remains a favorite of mine to this day.

The centerpiece of the issue is Part 2 of Daniel Collerton's "Irilian." As with last issue, Collerton describes a single section of the city, along with an adventure set in that part of Irilian. This part focuses attention on an abbey and an inn, both of which are given complete maps and both of which figure prominently in the scenario. The remainder of the article describes on living in Irilian, with an emphasis placed on what houses look like, family arrangements, coinage, and similarly mundane but nevertheless useful features. It's another great installment in a terrific series; it remains one of the highlights of White Dwarf during the period when I was reading it.

"Happy Landings!" by Thomas M. Price is a very good three-page article for Traveller. Price looks at starport design, an overlooked aspect of Traveller in my opinion (and not just because I worked on a book concerning this topic). What makes the article especially good are the half dozen or so sample maps included with it. Traveller characters spend an awful lot of time in starports; having more examples of possible layouts is this extremely helpful to the harried referee. This was another favorite of mine. "Arms Talk" by Oliver Dickinson is a discussion of damage absorption in RuneQuest. It's a fairly dense little essay, filled with plenty of musings about RQ's combat system. At the time, I wasn't playing the game, so I paid little heed to it. Nowadays, I wouldn't give it much attention either, since the complexities of the combat system are my least favorite aspects of RuneQuest.

"And Some Came Riding" is a fun installment of "Fiend Factory," describing several new D&D monsters that make use of mounts of one type or another. I especially like the Bug Riders, insect men who make use of a variety of arthropods as riding beasts. "Bujutsu" by Graeme Davis details Japanese weapons for use by AD&D monks, which was a well worn genre of article in the gaming magazines of the '80s. Finally, there's the first appearance of the comic Gobbledigook by Bil (who, I believe, is Bill Sedgwick, who did art for Games Workshop). I loved many of White Dwarf's comics, including Gobbledigook, so it was great seeing his debut in this issue.

Issue #42 of White Dwarf is an excellent one, perhaps one of the best I ever owned. The mix of D&D, Call of Cthulhu, and Traveller material was welcome, since they were my three main RPGs back in the days of my youth. Even now, they remain among my favorites. It's a real pleasure to revisit issues like this one and I look forward to those that follow it, as I recall that many of them are just as superb as this one.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers