James Maliszewski's Blog, page 106

July 5, 2022

Postal Humor

I'm not completely certain when the practice began – I should probably scour through my back issues to check – but I can't help but find the fake envelopes that graced the White Dwarf letters page amusing. Here are some representative examples from issues #39, #40, and #41 respectively. I'll try to pay closer attention to them when I re-read each new issue, in case there are more that are worthy of sharing.

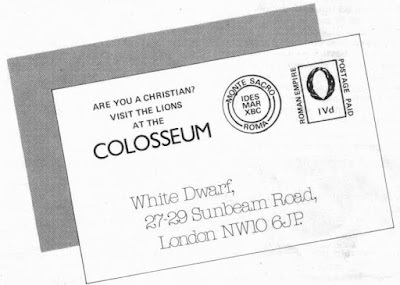

White Dwarf: Issue #41

My memory of White Dwarf is of a magazine whose articles were largely devoted to Dungeons & Dragons, Traveller, and RuneQuest (and, later, Call of Cthulhu), hence my great enjoyment of it. This estimation is especially true of issue #41 (May 1983), which includes material for all three of those RPGs (CoC material is in the near future, however). John Harris provides the issue's cover illustration, another science fiction piece of the sort that, to my recollection at least, was much more common for White Dwarf than for Dragon.

My memory of White Dwarf is of a magazine whose articles were largely devoted to Dungeons & Dragons, Traveller, and RuneQuest (and, later, Call of Cthulhu), hence my great enjoyment of it. This estimation is especially true of issue #41 (May 1983), which includes material for all three of those RPGs (CoC material is in the near future, however). John Harris provides the issue's cover illustration, another science fiction piece of the sort that, to my recollection at least, was much more common for White Dwarf than for Dragon. Ian Livingstone's editorial mentions the closures of both SPI and Heritage Models as evidence that the faddishness of roleplaying and wargaming may be fading. He opines that, in the 1970s, it was much easier for a company "to churn out mediocre games" and not suffer financially as a consequence. In the '80s, though, businesses that engage in such behavior is no longer sustainable as consumers become more selective in their purchases. There's definitely some truth to what he says, though, at least in the case of SPI, its demise was partly due to enemy action by TSR. Still, it's useful to be reminded of the cyclical nature of the hobby's popularity.

"Battle Plan!" by Allan E. Paull is an adjunct to last issue's "Dungeon Master General" article, in which he offered up a simple mass combat system for use with D&D. This time he presents both game statistics and tactical information for the armies of dwarves, elves, kobolds, and orcs. Not having made use of Paull's rules, I don't know how well they work in play, but the information he provides in this article strikes me as quite helpful. Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" takes a look at several novels of the time, the only one of which that I recall ever reading is Frank Herbert's The White Plague. Langford likes the novel, with some reservations, which, in my opinion, is a blanket statement that could be applied to most of the author's oeuvre.

"Open Box" reviews three products, starting with GDW's The Solomani Rim. Reviewer Andy Slack likes it better than The Spinward Marches, giving it 9 out of 10. In large part, his preference relates to the much higher production values and ease of use in the later product. Marcus L. Rowland reviews Yaquinto's Man, Myth, & Magic, along with its first two adventures, Death to Setanta and The Kingdom of the Sidhe. He didn't think too highly of any of them, giving them ratings of 5, 4, and 6 out of 10 respectively. Finally, there's a review of FGU's Star Explorer, a boardgame derived from its RPG, Starships & Spacemen. The reviewer, Allan E. Paull, found the game fun and well balanced, giving it a 9 out of 10.

"A Tasty Morsel" by Oliver Dickinson is another installment in his series of Gloranthan fiction, in which he tells the story of Griselda's exploits in New Pavis. Like most of these stories, it's quite enjoyable, particularly if you like Glorantha or picaresque tales. "Sorcerous Symbols" by Peter Hine is a fascinating article devoted to introducing magical marks and sigils into D&D as an alternative to scrolls and other expendable magic items. Hine presents not only examples of such sigils but a system for producing them, including the costs and time required to do so. It's a solid set of variant rules that a referee might find useful in certain types of campaigns.

"The Snowbird Mystery" by Andy Slack is an espionage-related adventure for Traveller. The scenario makes use of both the Explorer Class Scoutship introduced in issue #40 but also an accompanying article, "The Covert Survey Bureau." The Bureau is an Imperial spy agency that occasionally makes use of freelance operatives, hence their utility in an ongoing Traveller campaign. The adventure itself revolves around a corrupt governor's efforts to hide his illicit activities from the Empire, as well as a rivalry between the CSB and Naval Counter Intelligence. The resulting adventure is quite complex and includes plenty of scope for further development.

"Unarmed Combat II" by Oliver Dickinson is based on a collection of submissions and comments by readers regarding the best ways to expand and further develop unarmed combat in RuneQuest. It's an interesting article in that it doesn't settle on a single approach, but instead offers a number of options from which to choose. Being something of a rules tinkerer myself, I can't help but appreciate this approach. "Assignment: Freeway Deathride!" by Marcus L. Rowland is a scenario for use with Car Wars, a game I don't recall seeing supported much in the pages of White Dwarf.

Part III of "Inhuman Gods" by Phil Masters offers up yet more monstrous deities, like the lava children and grimlocks of the Fiend Folio. I don't wish to be too critical of this series, because I know I would have adored it as a younger person. From the vantage point of today, though, I nevertheless question its utility, especially for the more obscure (and rarely used) monsters of AD&D. Inspired by the movie, TRON, Paul McCree has penned "Discs as Weapons in AD&D," which does just that. He presents eight magical disc-shaped throwing weapons, a few of which have unique uses and effects. The biggest takeaway from this article for me, though, is a reminder of just how much of the content of D&D and other RPGs depends on "borrowing" from other media. The hobby is and always has been a creative goulash.

Issue #41 certainly held my attention, anchored by its superb Traveller material. As I have no doubt said on several occasions previously, White Dwarf published some of the best Traveller material outside of GDW's own. If you were a huge fan of the game as I was (and am), this was frequently a must-have periodical. I look forward to seeing more such material in coming issues, along with support for some of my other favorite RPGs. Speaking only for myself, we are entering the Golden Age of White Dwarf.

July 4, 2022

Rod Serling and CAS

I've often remarked on this blog how rare it is for the works of H.P. Lovecraft or Robert E. Howard to receive good adaptations in visual media and I think I'm more than justified in saying so, but at least HPL and REH got adaptations, no matter how poor. The same cannot be said for Clark Ashton Smith, whose pulp fantasies have left almost no footprint in contemporary popular culture, despite his being one of the most popular and influential writers to have written for Weird Tales during the Golden Age of the Pulps.

I've often remarked on this blog how rare it is for the works of H.P. Lovecraft or Robert E. Howard to receive good adaptations in visual media and I think I'm more than justified in saying so, but at least HPL and REH got adaptations, no matter how poor. The same cannot be said for Clark Ashton Smith, whose pulp fantasies have left almost no footprint in contemporary popular culture, despite his being one of the most popular and influential writers to have written for Weird Tales during the Golden Age of the Pulps. Of course, "almost no footprint" is not the same as "no footprint." As it turns out, one of Clark Ashton Smith's stories has been adapted – and by Rod Serling no less. During the third season of his 1970–1973 television anthology series, Night Gallery, there was an episode that adapted, albeit loosely, Smith's 1931 tale, "The Return of the Sorcerer." Compared to the groundbreaking The Twilight Zone, Night Gallery is somewhat more uneven in quality. However, it does feature a number of genuinely excellent episodes, most which focus on horror or occult subjects, thus giving the series a different overall tone to its illustrious predecessor.Though "The Return of the Sorcerer" is not one of the show's best episodes, let alone a completely faithful adaptation, it's not without its charms. The primary one is the performance of Vincent Price as John Carnby, the story's titular sorcerer. Price is always a pleasure to watch, even (especially?) when he's hamming it up, as he does here. Bill Bixby plays the translator of Arabic whom Carnby hires (called Ogden in Smith's original and Noel Evans here) to help him decipher a passage from the Necronomicon. The broad outline of the story is the same as its source material, though there are a number of additions that serve no real purpose. Chief among them is the creation of a new character, Fern (Tisha Sterling), who is Carnby's assistant and whose sole purpose in the TV narrative is to add some titillation. I find that odd, because if any Weird Tales author knew when to make good use of sensuality, it was Clark Ashton Smith and he saw no need of it here.

As adaptations go, it's not the worst. It's certainly closer to its source than, say, Conan the Barbarian, but it's nevertheless not something I'd urge anyone to seek out. The episode is more of an oddity than anything else, a unique example of Hollywood taking notice of Smith. Given the treatment Lovecraft and Howard have received over the years, perhaps it's just as well that the Bard of Auburn has largely been ignored.

The Mass Combat Fantasy Role-Playing Game

Though I was (eventually) an avid reader of White Dwarf, my direct experience with most of Games Workshop's other products was quite limited. I largely missed out on games like Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play until many years after the fact and even then my experience of it was cursory. That said, I do remember quite vividly the original marketing campaign for the very first edition of Warhammer, featuring the advertisement below.

Though I never bought the game – primarily because I never saw it in any of the hobby shops I frequented – I was nevertheless greatly intrigued by it. Warhammer's subtitle of "the mass combat fantasy role-playing game" intrigued me greatly. Around the time this was released (1983), I had begun to see a need for a stronger integration between personal and mass combat in roleplaying games. Consequently, Warhammer caught my attention. Had I been able to find a copy locally sooner, I likely would bought a copy. By the time I could, I had already read the lukewarm reviews of it in Dragon and so decided to pass on it. I now rather regret that, since that original edition is probably the only one whose complexity is within the range my feeble brain can handle. Ah, well!

Though I never bought the game – primarily because I never saw it in any of the hobby shops I frequented – I was nevertheless greatly intrigued by it. Warhammer's subtitle of "the mass combat fantasy role-playing game" intrigued me greatly. Around the time this was released (1983), I had begun to see a need for a stronger integration between personal and mass combat in roleplaying games. Consequently, Warhammer caught my attention. Had I been able to find a copy locally sooner, I likely would bought a copy. By the time I could, I had already read the lukewarm reviews of it in Dragon and so decided to pass on it. I now rather regret that, since that original edition is probably the only one whose complexity is within the range my feeble brain can handle. Ah, well!

July 3, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Blade of the Slayer

An aspect of the Golden Age of the Pulps I find especially congenial is the freedom with which its authors borrowed from and included homages to the works of their comrades. H.P. Lovecraft famously encouraged his fellow Weird Tales fictioneers to take whatever they wished from his tales and make use of them as they saw fit; he, in turn, did the same. It was all in good fun and speaks to the easy collegiality of those bygone days (something that, perhaps unsurprisingly, reminds me of the early days of the Old School Renaissance as well).

An aspect of the Golden Age of the Pulps I find especially congenial is the freedom with which its authors borrowed from and included homages to the works of their comrades. H.P. Lovecraft famously encouraged his fellow Weird Tales fictioneers to take whatever they wished from his tales and make use of them as they saw fit; he, in turn, did the same. It was all in good fun and speaks to the easy collegiality of those bygone days (something that, perhaps unsurprisingly, reminds me of the early days of the Old School Renaissance as well). I was reminded of this when I recently re-read "The Blade of the Slayer," the fourth of Richard L. Tierney's Cthulhu Mythos-tinged historical fantasies featuring Samaritan gladiator-turned-Gnostic-magician Simon of Gitta. The tale originally appeared in the first issue of Pulse Pounding Adventure Stories (December 1986), a fanzine produced by Cryptic Publications that featured artwork by Stephen Fabian. The 'zine was very short-lived, with only two issues, the second of which (released in December 1987) also included another Simon of Gitta yarn.

"The Blade of the Slayer" takes place in January, A.D. 32, which is relatively early in the career of Simon, as he travels through Parthia on the run from the agents of Rome. The story's action picks up quickly, with Simon evading a band of cutthroats in the desert. While attempting to hide, he encounters an old man, "tall and white-bearded, clad in a dark greenish robe inscribed with the symbols of the Persian Magi."

"Ho, stranger." The voice of the old man was nearly as thin as the cold wind. "Why do you come here to the site of the First City?"

"The–what?" Simon rose from his fighting crouch and approached the old man cautiously. "What are you talking about–?"

"And you have not heard that the spirit of the First Slayer, who founded it, still lingers about this ridgetop, waiting for unwary strayers?"

Simon glanced about at the numerous worn boulders, at the dry grasses blowing under the chill wind. "Aye, I've heard such tales. But, surely, no city ever stood here–"

"The legend is true. No outsider is safe in this place. You must go."

Simon is more concerned with his immediate safety and so is not put off by the warnings of the Magus. He beseeches the old man to hide for a short time, assuring him he has no interest in anything else. The old man relents, leading him into "a small room carved from the living rock and meagerly furnished with a cot, a wooden table, and two stools." He offers Simon some food, but again warns him about the spirit of the First Slayer, which the old man claims will overwhelm the Samaritan without magical protection. Simon scoffs and boasts that he, too, "[has] been trained in magical arts by Parthia's very own Magi."

"Aye, I know you now," said the oldster, his manner becoming a bit less suspicious. "You are Simon of Gitta, a pupil of the Archimage Daramos. I saw you several months ago, when I and several other priests of my order visited Daramos in Persepolis. Daramos mentioned to us that you were his most accomplished adept."

Simon, too, relaxed a bit more. "Thank you. But your memory is better than mine. I recall your visit, but not your name–"

"I am K'shasthra, priest of the Order of the High Guardians. At least one adept of our Order is always stationed here to guard the secret that–that for now must be kept from mankind. We have kept guard thusly for nearly two years. So much I may reveal to you, who have already been initiated into many secrets of the Magi. Perhaps I shall tell you more–but only with the understanding that the outer world must never know, until the Order has decided that the time is right."

In time, K'shasthra recognizes Simon as a powerful ally and agrees to reveal the secret his Order hides from the rest of mankind. The cave in which the old man dwells is part of a series of underground chambers that were dug beneath the First City, reduced to dust after thousands of years. Despite its name, the First City was actually "a walled fortress, founded by the First Slayer in fear of many who, fired by his example, sought to pursue and slay him."

"But the Slayer was under the curse of the great world-creator Achamoth," K'shasthra went on, "–the Demiurge who has fashioned the First Men to serve him. For his rebellion a Mark was set upon the Slayer; all who saw it shunned him in fear, and he was cursed to leave his city to his followers and wander forever over the face of the earth, hating and slaying, spreading new hatred and death."

"You mean," gasped Simon, "–this was–the city of Enoch …?"

The strength of the Simon of Gitta stories is the way that Tierney deftly blends the history, myths, and religions of the ancient world – including those of the Bible, as in this case – with all manner of occult and Lovecraftian nuttery to present compelling, almost Howardian tales of blood and thunder. Likewise, Tierney regularly engages in the same kinds of borrowings, homages, and in-jokes as his Weird Tales forebears. In this particular case, he does more than simply have Simon's saga intersect with that of the Biblical first murderer. He brings him into contact with another pulp fantasy character inspired by those same stories. The result is every bit as fun as those of Lovecraft, Howard, or Smith, hence my fondness for "The Blade of the Slayer."

The saga of Simon of Gitta has long been out of print. Fortunately, Pickman's Press has collected them all into a single volume very recently and I highly recommend them to anyone interested in this unusual series of sword-and-sandal stories.

June 30, 2022

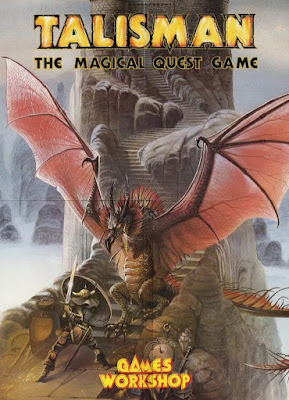

Retrospective: Talisman

There's a lot that could be said about the creative and commercial ecosystem created by the publication of Dungeons & Dragons in 1974. Chief among them is that, while D&D and many of its imitators did indeed sell well, those sales were nevertheless minuscule compared to traditional boardgames or even the burgeoning fields of electronic and video games. That's why many RPG publishers, TSR foremost among them, quite quickly attempted to find ways to make inroads into the wider games market. The various incarnations of the D&D Basic Set were one prong of this strategy, attempting to make roleplaying less arcane and more accessible to those not already immersed in wargaming or fantasy and science fiction. Another prong was the creation of more conventional games that borrowed thematic and esthetic elements of RPG in order to generate greater interest in them. Aside from Dungeon! (which was actually created before the publication of D&D but published later), I get the impression that most of these fantasy-themed boardgames weren't all that successful – or at least weren't as successful as their publishers had hoped they were going to be. The only other exceptional that immediately springs to mind is Games Workshop's Talisman (The Magical Quest Game), which first appeared in 1983. I say this because, unlike all the other such games from this time period, Talisman is the only one that's still in print today. There's even a digital version of the game.

There's a lot that could be said about the creative and commercial ecosystem created by the publication of Dungeons & Dragons in 1974. Chief among them is that, while D&D and many of its imitators did indeed sell well, those sales were nevertheless minuscule compared to traditional boardgames or even the burgeoning fields of electronic and video games. That's why many RPG publishers, TSR foremost among them, quite quickly attempted to find ways to make inroads into the wider games market. The various incarnations of the D&D Basic Set were one prong of this strategy, attempting to make roleplaying less arcane and more accessible to those not already immersed in wargaming or fantasy and science fiction. Another prong was the creation of more conventional games that borrowed thematic and esthetic elements of RPG in order to generate greater interest in them. Aside from Dungeon! (which was actually created before the publication of D&D but published later), I get the impression that most of these fantasy-themed boardgames weren't all that successful – or at least weren't as successful as their publishers had hoped they were going to be. The only other exceptional that immediately springs to mind is Games Workshop's Talisman (The Magical Quest Game), which first appeared in 1983. I say this because, unlike all the other such games from this time period, Talisman is the only one that's still in print today. There's even a digital version of the game.Talisman is a competitive game. Two to six players contend with one another in an attempt to reach the center of the game board, where the Crown of Power is located. Each player selects a hero card, which includes game statistics, including special abilities that differentiate one hero from another. Play consists of rolling a die to determine how many spaces a player can move his hero around the board. Depending on the space his hero enters, the player has to draw one or several cards. These cards can depict anything from monsters to fight, objects to find, or even helpful strangers to aid the hero. Interestingly, some cards permanently alter the space for which they're drawn, meaning that other heroes who enter them later must contend with their effects. This is especially true of monsters that aren't defeated: they remain their until someone slays them.

The board is divided into three concentric rings, each one smaller than the previous one – and filled with greater danger. Getting between the three rings is difficult, unless the hero has improved his abilities and acquired beneficial items through battle and the luck of the draw. Talisman thus has a kind of leveling mechanic built into it, which each ring representing a different level of challenge and only heroes whose players have taken the time to build them up will have much chance of success. Notice I wrote "chance of success." That's because Talisman is very random game, with so many of its elements determined either by cards or the roll of dice. That's not to say there's no strategy involved in its play, but the vast majority of its outcomes are determined by random means.

This randomness will no doubt be frustrating to many players, but, for others, that's a big part of the fun. Each game is quite unpredictable and there's no guarantee that even a seasoned player of the game will come out ahead of a total neophyte. Of course, Talisman includes the possibility of direct player versus player action too. Whenever a hero enters the same space as another, they can fight and the winner can steal an item or money from the defeated hero (as well as losing a life – all heroes have four before they are out of the game). This adds another level of uncertainty (and sometimes frustration) to the game and increases its appeal.

Talisman is one of those games that roleplayers frequently keep nearby to play during those times when not everyone can show up for a session. Because of the randomness of its gameplay, which only increases if one makes use of even one, never mind several, of its expansions, this is not a short game to play. In my experience, it was rare to complete a game of Talisman in less than 90 minutes and I recall some games that lasted three hours or more. Still, if you don't mind the outsize role that chance plays in the outcome of most games, Talisman is quite fun. There's a reason the game is still published almost four decades after its initial release. It's one of the classics of the hobby and I have many fond memories of playing it with friends.

June 28, 2022

"The Thinking Magazine for Adventure Gamers"

Issue #40 of White Dwarf (April 1983) featured an advertisement for the first issue of TSR UK's Imagine, which premiered the very same month.

In addition to the usual hyperbole, the ad is also notable for making use of the term "adventure gaming" to describe the hobby it services. In certain quarters, "adventure game" was preferred to "roleplaying game," in part, I think, because "roleplaying" was at the time more strongly associated with the field of psychology. I don't recall ever encountering the term often back in my youth. To my American ears, it sounds very British, but that might just be confirmation bias on my part. Regardless, it doesn't appear to have been widespread in its use, even within the United Kingdom, as evidenced by the title of Games Workshop's own foray into the field.

In addition to the usual hyperbole, the ad is also notable for making use of the term "adventure gaming" to describe the hobby it services. In certain quarters, "adventure game" was preferred to "roleplaying game," in part, I think, because "roleplaying" was at the time more strongly associated with the field of psychology. I don't recall ever encountering the term often back in my youth. To my American ears, it sounds very British, but that might just be confirmation bias on my part. Regardless, it doesn't appear to have been widespread in its use, even within the United Kingdom, as evidenced by the title of Games Workshop's own foray into the field.

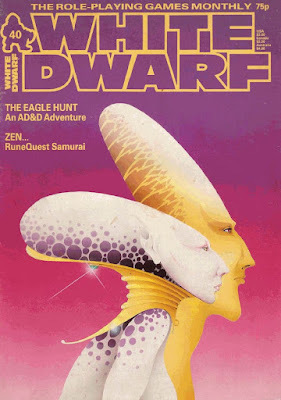

White Dwarf: Issue #40

I have no idea what artist Emmanuel's cover to issue #40 of White Dwarf (April 1983) is supposed to depict. Despite that, it's exactly the kind of cover I strongly associate with the magazine: weirdly evocative and vaguely science fictional or fantasy in its subject matter. Somewhat relatedly, Ian Livingstone's editorial notes that fantasy RPGs remain much more popular than science fiction ones and he wonders why that is. It's a question I regularly ponder myself. The closest I've come to an answer is that fantasy is a more strongly codified and, therefore, familiar gaming genre, where even those RPGs that deviate from the Tolkien-descended consensus tacitly acknowledge its supremacy. The same is not true of science fiction, with its welter of sub-genres and approaches.

I have no idea what artist Emmanuel's cover to issue #40 of White Dwarf (April 1983) is supposed to depict. Despite that, it's exactly the kind of cover I strongly associate with the magazine: weirdly evocative and vaguely science fictional or fantasy in its subject matter. Somewhat relatedly, Ian Livingstone's editorial notes that fantasy RPGs remain much more popular than science fiction ones and he wonders why that is. It's a question I regularly ponder myself. The closest I've come to an answer is that fantasy is a more strongly codified and, therefore, familiar gaming genre, where even those RPGs that deviate from the Tolkien-descended consensus tacitly acknowledge its supremacy. The same is not true of science fiction, with its welter of sub-genres and approaches."Zen and the Art of Adventure Gaming" by Dave Morris reminds us that we're solidly into the '80s and its fascination with all things Japanese. His article is an attempt to present feudal Japan in RuneQuest terms, with new weapons, armor, and skills, in addition to a very brief treatment of kami and magic. Being on something of a RuneQuest kick lately, I found this article a welcome one, though its brevity limits its utility considerably. I now find myself regretting that I never picked up Land of Ninja during the years when Avalon Hill was publishing RQ under license from Chaosium.

"Dungeon Master General" by Alan E. Paull presents a system for handling large scale combats in Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. Paull's system is a relatively simple one that eschews miniatures and downplays precise measurements in favor of speed and ease of use. Consequently, the system is loose and relies on referee judgment and common sense in many areas, such as the adjudication of morale. Not having used it myself, I can't speak to how well it works, but I nevertheless appreciate articles like this. I've long been of the opinion that D&D is in need of a mass combat system that does not expect the referee to break out a sand table every time he wishes to simulate a clash between armies. Paull's system may or may not succeed in doing this to most people's satisfaction – I suspect the latter – but it's a worthy project nonetheless.

Dave Langford's second "Critical Mass" column focuses on two authors whose works have been discussed on this blog in the past: Robert Asprin and Stephen R. Donaldson. In the case of Asprin, Langford reviews Myth Conceptions, the third in the author's Myth series. Langford doesn't think much of the book or its humor; I can't say that I disagree with him. It's very difficult to write a series of humorous novels without eventually descending into an unintentional parody and that's more or less what happened to Asprin. As for Donaldson, Langford reviews White Gold Wielder, the third and final book in the second trilogy of Thomas Covenant. Langford doesn't think better of this novel and, again, I can't really disagree with him. The second trilogy showed promise early on, with the protagonist being much less awful than he was in his previous outing, but it's still a convoluted, self-serious slog with a couple of interesting ideas that don't justify the time I invested in reading it.

"Open Box" reviews Soloquest 2: Scorpion Hall for RuneQuest, giving it an 8 out of 10. Also reviewed are a quarter of AD&D modules: Hidden Shrine of the Tamoachan (8 out of 10), Ghost Tower of Inverness (8 out of 10), White Plume Mountain (8 out of 10), and Dwellers of the Forbidden City (5 out of 10). Perhaps I am biased, but I find it difficult to believe that Dwellers of the Forbidden City rates only a 5 or that either Ghost Tower of Inverness or White Plume Mountain, both of which are contrived funhouse modules, deserve ratings as high as they received. Chacun à son goût. Illuminati receives a 7 out of 10, while Starstone, a generic fantasy module published by Northern Sages (and with which I am unfamiliar) receives a 9 out of 10.

"The Eagle Hunt" by Marcus L. Rowland is an AD&D scenario for 1st–3rd level characters. Its premise is that an ancient artifact, the titular Green Eagle, has been stolen from the king's treasure vault and the two detectives dispatched to locate it have themselves gone missing, thereby necessitating a public reward of 20,000gp for anyone who can recover it. "The Eagle Hunt" is a lengthy and engaging adventure, quite different from the usual low-level scenarios one regularly sees. Likewise, the Green Eagle's true purpose, if discovered, has the potential to open up interesting possibilities in a D&D campaign.

"Trading" by Oliver Dickinson presents a simple trade system for use with RuneQuest, one vaguely reminiscent of that found in Traveller (not that that's a bad thing). Speaking of Traveller, Andy Slack offers up "Explorer Class Scoutships," a detailed look at a new type of starship, complete with game stats and deckplans. Part II of "Inhuman Gods" by Phil Masters treats readers to the deities of yet more non-human beings, such as the firenewts, flinds, and frogmen. "RuneQuest Characters" by Nelson Cunningham provides the code for a GAP (game assistance program) intended to generate random RQ characters. I love that the article includes a section entitled "What to do when it crashes." Good times! Finally, "Treasure Chest" gives us six more D&D magic items, because we can never have too many magic items, can we?

Issue #40 is a very strong issue, filled with plenty of meaty and imaginative articles, many of which have a unique flair that differentiates them from what I saw in the pages of Dragon and other American gaming periodicals of the same era. Re-reading this issue, I found myself unexpectedly nostalgic for the White Dwarf of old, before the magazine became wholly devoted to Warhammer and its spin-offs. I consider myself fortunate to entered the hobby at the time I did. We shall not see its like again.

June 27, 2022

Everything Old is New Again

I've been re-reading the RuneQuest second edition rulebook. In the fifth chapter (Basic Magic), there's a note under the section "Learning Spells" that is (perhaps) an amusing reflection of the decade in which the book was written – and, ironically, relevant again more than four decades later.

NOTE: To buy a variable spell, a character must pay the cost of each lower point spell as well as the level he wishes to buy. In other words, to obtain Healing 3, Healing 1 and Healing 2 must also be bought, a total cost of 3000 L.

If the referee prefers a campaign with lots of money available, the cost of spells should be raised. Inflation, you know.

June 26, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: Witch of the Demon Seas

I frequently reflect on my own lack of industry, especially when compared to nearly all of the writers I discuss in my Pulp Fantasy Library posts. These energetic men and women cranked out exciting stories by the ream – so many, in fact, that they sometimes had to resort to using a variety of noms de plume to ensure the magazines would publish their submissions (many of which had policies, formal or informal, against the inclusion of more than one story by the same author in a single issue).

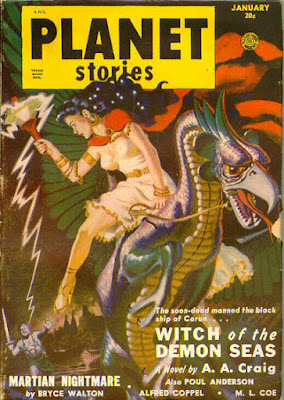

I frequently reflect on my own lack of industry, especially when compared to nearly all of the writers I discuss in my Pulp Fantasy Library posts. These energetic men and women cranked out exciting stories by the ream – so many, in fact, that they sometimes had to resort to using a variety of noms de plume to ensure the magazines would publish their submissions (many of which had policies, formal or informal, against the inclusion of more than one story by the same author in a single issue). I bring this up because this is precisely what happened in the case of "Witch of the Demon Seas," which first appeared in the January 1951 issue of Planet Stories. Though credited to "A.A. Craig," the yarn is actually the handiwork of Poul Anderson, another of whose stories is featured in the same issue under his usual byline. Like many pulp fictioneers, Anderson had an incredible work ethic: sixteen of his short stories and novellas were published the same year as "Witch of the Demon Seas." It's difficult not to feel inadequate when faced with such a remarkable output.

Though nowadays Anderson is most remembered for his science fiction, notably his tales of Nicholas Van Rijn, David Falkayn, and, of course, Dominic Flandry, he was also an accomplished writer of fantasy. Three Hearts and Three Lions is perhaps the best known of his fantasies, at least for players of roleplaying games, but The Broken Sword is, in my opinion, equally worthy of admiration (both appear in Gary Gygax's Appendix N, for what it's worth). Pulp writers had to be omnivorous if they wanted to make a living at writing, hence the existence of stories, such as this one, that might broadly be described as "fantasy" (or perhaps sword-and-planet, which was the bread and butter of Planet Stories during its 71-issue run).

Regardless, "Witch of the Demon Seas" certainly takes place on another world, one whose surface is almost entirely covered by water. What civilization exists can be found on numerous island kingdoms, such as the Thalassocracy of Achaera, whose ruler is Khroman the Conqueror. Khroman is "a huge man, his hair and square-cut beard jet-black despite middle age, the strength of his warlike youth still in his powerful limbs." He's also honorable, which we learn early in the story, when he tells his advisor, Shorzon the Sorcerer, that he intends to treat his recently defeated enemy, the fair-haired pirate Corun, with respect, as he is "the bravest enemy Achaera ever had."

When Khroman interrogates him, Corun reveals much about his origins and the reasons for his turn to piracy. Come to think of it, the interrogation reveals a fair bit about Khroman as well.

Khroman stared at him in puzzlement. "But why did you ever do it?" he asked finally. "With your strength and skill and cunning, you could have gone far in Achaera. We take mercenaries from conquered provinces, you know. You could have gotten Achaeran citizenship in time."

"I was a prince of Conahur," said Corun slowly. "I saw my land invaded and my folk taken off as slaves. I saw my brothers hacked down at the battle of Lyrr, my sister taken as concubine by your admiral, my father hanged, my mother burned alive when they fired the old castle. They offered me amnesty because I was young and they wanted a figurehead. So I swore an oath of fealty to Achaera, and broke it the first chance I got. It was the only oath I ever broke, and still I am proud of it. I sailed with pirates until I was big enough to master my own ships. That is enough of an answer."

"It may be," said Khroman slowly. "You realize, of course, that the conquest of Conahur took place before I came to the throne? And that I certainly couldn't negate it, in view of the Thalassocrat's duty to his own country, and had to punish its incessant rebelliousness?"

"I don't hold anything against you yourself, Khroman," said Corun with a tired smile. "But I'd give my soul to the nether fires for the chance to pull your damned palace down around your ears!"

"I'm sorry it has to end this way," said the king. "You were a brave man. I'd like to drain many beakers of wine with you on the other side of death." He signed to the guards. "Take him away."

Upon hearing this, Shorzon takes an interest in Corun, for reasons that soon become clear. Together with his daughter, Chryseis, the story's titular witch, he visits the pirate in his solitary cell. The sorcerer then offers him "life, freedom—and the liberation of Conahur!" Naturally, Corun doubts the wizard's sincerity, but Chryseis, a remarkable beauty, reassures him, "You can help us with a project so immeasurably greater than your petty quarrels that anything you can ask in return will be as nothing. And you are the one man who can do so."

"What do you want?"

"Your help in a desperate venture," said Chryseis. "I tell you frankly that we may well all die in it. But at least you will die as a free man—and if we succeed, all the world may be ours."

"What is it?" he asked hoarsely.

"I cannot tell you everything now," said Shorzon. "But the story has long been current that you once sailed to the lairs of the Xanthi, the Sea Demons, and returned alive. Is it true?"

"Aye." Corun stiffened, with sudden alarm trembling in his nerves. "Aye, by great good luck I came back. But they are not a race for humans to traffic with."

"I think the powers I can summon will match theirs," said Shorzon. "We want you to guide us to their dwellings and teach us the language on the way, as well as whatever else you know about them. When we return, you may go where you choose. And if we get their help, we will be able to set Conahur free soon afterward."

Corun shook his head. "It's nothing good that you plan," he said slowly. "No one would approach the Xanthi for any good purpose."

"You did, didn't you?" chuckled the wizard dryly. "If you want the truth, we are after their help in seizing the government of Achaera, as well as certain knowledge they have."

"If you succeeded," argued Corun stubbornly, "why should you then let Conahur go?"

"Because power over Achaera is only a step to something too far beyond the petty goals of empire for you to imagine," said Shorzon bleakly. "You must decide now, man. If you refuse, you die."

This is the proverbial offer that one cannot refuse, so, with some trepidation, Corun agrees. Shorzon and Chryseis then lead him to a fully-crewed vessel that will take them to the Xanthi, a race of inimical fish-men with a history of warring against the other peoples of the world. The ship leaves Achaera – without the knowledge of Khroman, I might add! – on a quest whose ultimate objective, Corun suspects, is far from virtuous. For the moment, though, he does not care, as he only wishes "to live! To die, if he must, under the sky!"

"Witch of the Demon Sea" is a delightful romp, filled with monsters, magic, sorcery, and swordplay. The characters, starting with Corun himself, are somewhat archetypal, let us say, but Anderson tells the story with such energy and enthusiasm that I soon didn't care. The story is interesting, too, because it contains elements that could be described as "secret sci-fi," thereby further muddying the waters regarding how to classify this yarn. For myself, I prefer to classify it as "fun" and leave it at that.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers