James Maliszewski's Blog, page 109

May 9, 2022

"The Playable One"

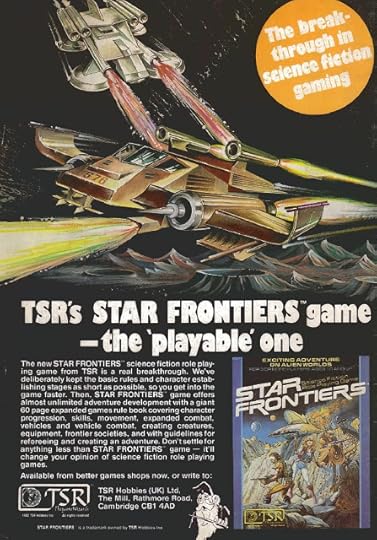

An unexpected joy of re-reading White Dwarf is coming across advertisements like this one for Star Frontiers, which, so far as I know, was unique to the UK market. The ad is interesting for several reasons, starting with the original artwork that accompanies it. Equally interesting, I think, is the inclusion of a cartoonish looking wizard as a kind of corporate mascot. Again, this seems unique to the UK market, though a similar wizard character does appear on the box of the 1982 TSR children's boardgame, Fantasy Forest. Both, I imagine, are callbacks to the old TSR wizard logo from the late 1970's to very early 1980s.

Most interesting of all, at least to me, is that the advertisement emphasizes the supposed playability of Star Frontiers over its competitors in the SF RPG market. At the time this ad appeared (1982), Traveller was likely the most popular and successful science fiction roleplaying game on the market, followed by Space Opera. I can certainly believe that Space Opera was widely seen as complex, but was Traveller viewed in the same way? My no doubt rose-colored memories don't include that perception at all, but that doesn't say much. Even given the sorts of hyperbole to which advertising is prone, I can't help but wonder about the claim that Star Frontiers "will change your opinion of science fiction role playing games."

May 8, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Right Hand of Doom

There can be denying that, during his lifetime, Robert E. Howard was an extremely successful – and popular – writer. Consequently, illustrations depicting his stories appeared on the cover of Weird Tales thirteen times, since the advertisement of a yarn by Howard served as a powerful enticement at the newsstand. Yet, like all writers for the pulps, he regularly encountered disinterest and rejection by his editors, most notably the mercurial editor of the Unique Magazine, Farnsworth Wright. Sometimes, REH would rework these rejected stories for resubmission elsewhere (or even again to Weird Tales). At other times, he simply abandoned these stories and it would not be until decades after his death that anyone even became aware of their existence, let alone had a chance to read them.

There can be denying that, during his lifetime, Robert E. Howard was an extremely successful – and popular – writer. Consequently, illustrations depicting his stories appeared on the cover of Weird Tales thirteen times, since the advertisement of a yarn by Howard served as a powerful enticement at the newsstand. Yet, like all writers for the pulps, he regularly encountered disinterest and rejection by his editors, most notably the mercurial editor of the Unique Magazine, Farnsworth Wright. Sometimes, REH would rework these rejected stories for resubmission elsewhere (or even again to Weird Tales). At other times, he simply abandoned these stories and it would not be until decades after his death that anyone even became aware of their existence, let alone had a chance to read them.Such is the case with "The Right Hand of Doom," a very early story of Puritan adventurer, Solomon Kane. The story was likely written and rejected sometime in the late 1920s or early 1930s, but its first publication didn't occur until 1968, when it appeared in Red Shadows, an anthology named after the Kane story of the same name. Produced by Donald M. Grant, Red Shadows was a limited run book, with fewer than 900 copies in its first printing. However, the book sold out quickly, thanks in part to the growing interest in Howard's original texts, unadulterated by the "revisions" of L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter. The inclusion of previously unknown tales like "The Right Hand of Doom" no doubt played a role as well.The story begins in a tavern, where a drunken man with "a high-pitched grating voice" boasts of the fact that a man is to hang out dawn.

"Roger Simeon, the necromancer!" sneered the grating voice. "A dealer in diabolic arts and worker of black magic! My word, all his foul power could not save him when the king's soldiers surrounded his cave and took him prisoner. He fled when the people began to fling cobble stones at his windows, and thought to hide himself and escape to France. Ho! Ho! His escape shall be at the end of a noose. A good day's work, say I."

But not everyone in the tavern is impressed by the boasts of the man, whose name we learn is John Redly. Seated near the fireplace is "a tall silent man" who was "gaunt, powerful and somberly dressed."

"I say," said he in a low powerful voice, "that you have this day done a damnable deed. Yon necromancer was worthy of death, belike, but he trusted you, naming you his one friend, and you betrayed him for a few filthy coins. Methinks you will meet him in hell, some day."

Redly is offended by such an accusation but chooses not to tangle with the man by the fireplace, whom the others in the tavern call "dangerouser than a wolf" – Solomon Kane. Redly likewise thinks little of the vengeance the necromancer swore to take on him. Now that Simeon was in the hands of the authorities, he could enjoy the wages of his betrayal in safety. Naturally, Redly is mistaken in this and, by the morning, he is dead in his bed and Kane is there to determine just how this happened.

"The Right Hand of Doom" is a very short story, just a few pages in length and it wastes few words on unnecessary dialog or description. If I have a complaint about the story, it's that there's very little action in it. Kane is almost passive in the story, which unfolds without his involvement. He is there to witness Simeon's revenge upon the man who betrayed him and then react to it. He rights no wrongs, as he usually does, nor is he ever in any danger. Instead, Kane is simply present, though Howard does a good job, I think, in depicting his resolute demeanor and upright character.

"The Right Hand of Doom" is thus a very different kind of pulp fantasy. It's essentially a ghost story of a sort, one you might tell around the campfire at night rather than a tale of heroic derring-do in the early 17th century like Howard's more well known stories of Solomon Kane. Perhaps that explains why "The Right Hand of Doom" was never published during Howard's lifetime: it's something of a departure from his usual style and subject matter. Personally, I'm fine with that and think it's a fun little tale of supernatural revenge well worth reading if you can find a copy.

May 6, 2022

Cross Pollination

Briefly: I am fine. Thank you to everyone who reached out to check in on me, concerned that my having not written a post in the last week portended something unpleasant. The truth is I simply wanted to take a break. Spring is here; the weather is warmer and now seemed a good time to start working on my garden, among other vernal chores. Regular posting will resume in due course.

Briefly: I am fine. Thank you to everyone who reached out to check in on me, concerned that my having not written a post in the last week portended something unpleasant. The truth is I simply wanted to take a break. Spring is here; the weather is warmer and now seemed a good time to start working on my garden, among other vernal chores. Regular posting will resume in due course.In the meantime, here's another question to keep you occupied: have you ever imported a rule from one RPG into another? That is, have you ever come across a rule (or rules interpretation) in one game that you liked so much that you thought a different game would benefit from its adoption? In my own case, I found the way that Empire of the Petal Throne handles the rolling of hit points upon gaining a new level so clever that I've made use of it in every level-based RPG with increasing hit points that I referee. For those unaware, EPT says that, once a new level is gained, the player rolls all his character's hit dice and adds up the total. If the sum is less than his character's current hit points, he gains no new hit points; if the sum is greater, it becomes the character's new hit point total. I like the rule because it evens out a PC's hit points over time while still respecting the inherent randomness of using dice.

What are your favorite rules you've borrowed from another game?

April 29, 2022

Changing Your Mind

I've often mentioned that, in my younger days, I inherited a number of prejudices against particular roleplaying games from the older gamers I knew at the time. Consequently, there were some RPGs about which I held decidedly negative opinions for a long time and it would be years before I re-evaluated them in light of direct experience rather than simply trusting the word of others. Mind you, I can't blame all of my gaming prejudices on others; I was – and am – quite capable of unthinking disdain all on my own.

Fortunately, I'm also capable of changing my mind from time to time. I can think of several RPGs I once viewed in a bad light for which I now have affection. Chaosium's RuneQuest is an example of this, though perhaps not the best one, because I think RQ is a game that's generally held in very high regard. That I didn't think much of it says more about my own peculiar initiation into the hobby than it does about anything else. No, when I think of a game about which I've wholly changed my original opinion it's not RuneQuest but Rolemaster.

My early experiences with Rolemaster were not positive ones. They left me with a deep dislike of the game, which I deemed too complicated and unwieldy for play. This was not a carefully considered opinion based on lengthy engagement with Rolemaster but instead a shallow reaction to a few sessions that proved uncongenial. I spent the next several decades firmly believing that Rolemaster was simply a terrible game and unworthy of my (or anyone else's) time.

That all changed a few years ago, when a friend of mine offered to run a Rolemaster campaign for me and several others. My friend was quite knowledgeable about Rolemaster, having run it for years. He assured me that the game wasn't nearly as complex as it seemed and that I'd enjoy myself. As it turned out, he was absolutely correct. I had a blast with the campaign and was very glad I'd had the chance to see Rolemaster in a new light. It's still far from my go-to game for fantasy roleplaying, but I now recognize that my earlier feelings toward it were misplaced. In the hands of a good referee, it's every bit as fun as any other RPG.

Has anyone else had a similar experience? Have you ever done an about-face on a roleplaying game of which you'd previously thought poorly? What changed your mind?

April 28, 2022

Rules of the House

I want to begin this post with a brief anecdote.

I want to begin this post with a brief anecdote. The other day, a friend of mine with whom I've gamed for many years, confessed to something he considered "embarrassing." What was the source of his shame? He recently tallied up the pages in the house rules document for a game he was refereeing and discovered, to his surprise, that it exceeded sixty pages. The horror! I was quick to reassure him that this was no cause for unease. Indeed, quite the opposite, since these rules were, in part, the accumulation of years of thought and play – tweaks to make the game "as [he] would like it to be," in the phrase from the afterword to OD&D.

My friend's reluctance to admit that he very thoroughly house ruled the game he was refereeing is not unique. Over the years, I've encountered quite a few people who have felt that the addition of house rules was somehow "wrong" and that the only "correct" way to play a RPG was exactly as its rules were written. I'm not quite sure of the origin of this mentality. If I had to guess, I'd lay the blame on the third edition of Dungeons & Dragons, part of whose culture is obsessed with "RAW" – "rules as written" – a term that I don't believe I ever heard prior to 3e. I don't want to lay the blame entirely on this edition; Gygax complained about rules lawyers all the way back in 1974, so the mentality has been a constant in the hobby, even if its prevalence seems to have increased in recent years.

I don't think I've ever played a single roleplaying game exactly as it was written. In some cases, this was due to ignorance or misreading of the rules. In other cases, it's because of the existence of a body of folklore that has supplanted the actual rules to the point that "everybody knows" this rule or that should be understood in a particular way (often contrary to the designer's intent). Yet, there are also examples of rules changes that are deliberate and the result of careful thought and consideration, added or subtracted to make the game run more like what the referee and players desire.

Like rules lawyers, this is a venerable tradition, predating the existence of OD&D itself and arising out of the traditions of miniatures wargaming. Arguably, the entire history of RPGs is, to borrow from Benjamin Jowett, a series of house rules to D&D, sometimes explicitly so. Neither Gary Gygax nor Dave Arneson played OD&D precisely as written. From a certain perspective, AD&D might even be called an elaborate set of OD&D house rules, with the game expanded and honed into something Gary found more congenial to the style of play he preferred. There's nothing wrong with house rules and I must confess to be baffled that anyone might seriously think there were.

That said, I do feel that, before one introduces house rules into one's campaign, it's important that one reads, understands, and tries to use the rules as they are written. "Ivory tower" house ruling, which is to say, pre-emptive house ruling before play has actual begun no longer sits well with me, even though (or perhaps because I have engaged in it in the past). I am now much more firmly of the opinion that house rules should arise from play and reflect dissatisfaction with how the actual rules work in a given campaign. In this context, I find house rules not merely laudable but in fact inevitable. Any referee running a long campaign will, I think, introduce house rules into play simply because no RPG ever written is so perfectly written that its rules work for every possible configuration of players.

Again, I'd like to stress that I generally don't think house rules should occur in a vacuum. They should be reflective of play, not to mention reflective of thoughtful engagement with the rules they're supposed to modify or replace. Taking the time to read and understand the rules of the game you're playing seems to me to be a prerequisite to the creation of any house rule. Perhaps I am odd but that strikes me as commonsensical, after the fashion of G.K. Chesterton's metaphor of the fence: "don't tear it down until you know why it was put up in the first place." I think that's sound advice and have tried to put into practice in my own campaigns.

There is no shame in house rules, because they are almost unavoidable if you play a game long enough. That's exactly as it should be, which is why OD&D ends with an exhortation to make the game as you would like it to be. Fight on!

April 27, 2022

Retrospective: Lankhmar: City of Adventure

I'm a sucker for fantasy cities. I'm not entirely sure of the precise origin of my fascination with them, but I have little doubt that Fritz Leiber's Lankhmar played a role in cultivating it. I was – and am – a huge fan of the tales of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Consequently, their home base, the City of the Black Toga, the City of Sevenscore Thousand Smokes, is forever lodged in my imagination as the fantasy city par excellence.

I'm a sucker for fantasy cities. I'm not entirely sure of the precise origin of my fascination with them, but I have little doubt that Fritz Leiber's Lankhmar played a role in cultivating it. I was – and am – a huge fan of the tales of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Consequently, their home base, the City of the Black Toga, the City of Sevenscore Thousand Smokes, is forever lodged in my imagination as the fantasy city par excellence.

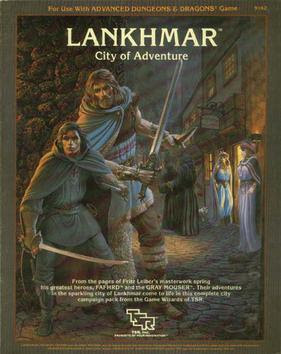

When TSR published Lankhmar: City of Adventure in 1985, there was no question about whether I'd buy it. Though I'd already seen both The Free City of Haven and Thieves' World (and likely a few other similar products), neither of them had the same kind of immediate appeal for me as did Lankhmar. I remember first seriously thinking about the possibilities of playing D&D in Nehwon after I got my copy of Deities & Demigods, but I never actually did so. With the release of this 96-page softcover book, however, I thought the time might have come to take the plunge at last.

Written by the trio of Bruce Nesmith, Douglas Niles, and Ken Rolston, Lankhmar: City of Adventure aims to do two things: describe the titular city as a roleplaying locale and provide rules and guidelines for playing Advanced Dungeons & Dragons in Nehwon. Of these two goals, the least interesting is the former, in large part because the implied setting of Gygaxian D&D is already very similar to that of Leiber's fiction. Most of what's needed is a different selection of monsters and deities – both of which this book provides in their own chapters – and a reduction in the prevalence of magic and you're most of the way there. With regard to magic, Lankhmar reduces it to two kinds, black and white, with most magic in Nehwon being black and, therefore, out of the hands of player characters. While perhaps a bit simplistic, it's not a terrible approach and I'm sympathetic to the designers who opted for it rather than creating an entirely unique magic system for Nehwon.

The description of the city is quite good and generally hews quite closely to Leiber's stories (all of which get summaries at the start of the book). The city is divided up into "districts," each of which has its own section where their most important locations are described. Each district has its own map, which fits onto the larger map of the entire city. Because even these district maps encompass a large amount of real estate, it'd be impossible to detail them entirely. To deal with this, there are portions of each map that are left blank and that are intended to be filled through the use of geomorphs presented in a little booklet found inside the back cover of Lankhmar. The referee can then fill in these blanks as he sees fit, in the process creating his own version of Lankhmar.

As impressive as the rest of Lankhmar: City of Adventure was – and it genuinely was well done – I soon found that all thoughts of running a campaign set in Leiber's world faded once I realized just how broadly useful that booklet of geomorphs was. I saw that TSR had given me the tools I needed to create my own large fantasy cities with relative ease. All I needed to do was photocopy the geomorphs I wanted from among the large selection Lankhmar provided and then fit them together as I wished. I must tell you I spent a lot of time at my local public library, making use of the Xerox machine to produce enough maps so that I could piece together a larger map of the cities of Emaindor. What fun!

In the end, it's difficult for me to disentangle my positive feelings toward Lankhmar from my memories of making use of those geomorphs. Though I do think the book does what it sets out to do quite well, what sticks with me now, decades later, is the way it inspired me to make my own cities in my own setting rather than using those that someone else had made. That's probably the highest compliment I can pay to any RPG product: it sparked my own creativity. By that measure, Lankhmar: City of Adventure is a very fine product indeed.

April 26, 2022

The Matter of France

Bulfinch's Mythology was very important to me as a kid. I regularly borrowed it from the library and read it cover to cover more times than I can recall. Though I was very enamored of the first two sections, which retold the myths of ancient Greece and the legends of King Arthur, it's the third part I've found myself thinking about lately. This is where I was first introduced to the tales of Charlemagne and his twelve paladins, names that meant little to me in my early childhood but that would come to mean a great deal more to me once I discovered Dungeons & Dragons.

Bulfinch's Mythology was very important to me as a kid. I regularly borrowed it from the library and read it cover to cover more times than I can recall. Though I was very enamored of the first two sections, which retold the myths of ancient Greece and the legends of King Arthur, it's the third part I've found myself thinking about lately. This is where I was first introduced to the tales of Charlemagne and his twelve paladins, names that meant little to me in my early childhood but that would come to mean a great deal more to me once I discovered Dungeons & Dragons.

The reason I've been thinking about it is that, as I mentioned last week, I'm playing in a Pendragon campaign at the moment and am having a great deal of fun. Pendragon, as I never tire of saying, is one of my favorite RPGs, one whose underlying mechanics do a terrific job of encouraging and supporting play that feels very much like what you might read in Sir Thomas Malory. Many others feel similarly, which is why, over the years, people have been borrowing Pendragon's mechanics for use in other mythic or historical settings.

I think that's a great idea and have kept an eye on several of these projects over the years, but the one that most interested me is Paladin, which aimed to do for the legends of King Charles the Great what Pendragon had done for King Arthur Pendragon. Riding the high of the Pendragon campaign, I finally pulled the trigger and bought a copy of Paladin last week and have been reading it ever since. The physical copy is a truly massive tome over 450 pages in length – and a beautiful one, too. The cover, as you can see, is quite inspiring and the interior art, while sparse, is similarly evocative. I'm not usually a fan of gilt edges for RPG books; in this case, it somehow seems appropriate.

Rules-wise, Paladin is quite similar to Pendragon, with a few changes to reflect its different cultural and historical context. For example, a character's extended family is given much greater emphasis in Paladin. Players are encouraged to make their characters related to one another, in an effort to better emulate the epic medieval poems about Charlemagne and his paladins. Relatedly, characters age faster (and, therefore, die sooner) than do characters in Pendragon, which lends a very different flavor to campaigns. Paladin is also a bit more "magical" than Pendragon, in that divine miracles are within the grasp of player knights, who are loyal to Charlemagne and adhere to the tenets of the Christian faith. Many of their adversaries are wicked sorcerers, who command the powers of Hell. The result is a game that is familiar to anyone who's played Pendragon but by no means identical.

This is a game I'd very much like to try refereeing at some point in the future. Precisely because the Matter of France is not as well known in the English-speaking world as the Matter of Britain, I think Paladin could possess a degree of "freshness" that might be lacking for gamers who've known about Arthur all their lives. This gives it the potential, I think, for being the basis of an excellent campaign, especially when tied to the terrific mechanics of Pendragon. I have no idea when I'll have the time to take up Paladin seriously – I've already got more on my plate than I can handle – but it's nevertheless a rare example of a new RPG that I feel I must play. The only question is when.

White Dwarf: Issue #35

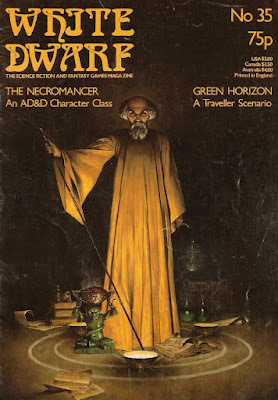

Issue #35 of White Dwarf (October 1982) features a wonderfully evocative cover by Les Edwards. Covers like this one highlight one of the most visible differences between WD and Dragon. Dragon's cover artwork was, in general, very good, but much of it felt "game-y" to me, whereas White Dwarf's cover illustrations looked like the kind you might see on fantasy and science fiction novels – no surprise, since many of the pieces originally did appear on novels).

Issue #35 of White Dwarf (October 1982) features a wonderfully evocative cover by Les Edwards. Covers like this one highlight one of the most visible differences between WD and Dragon. Dragon's cover artwork was, in general, very good, but much of it felt "game-y" to me, whereas White Dwarf's cover illustrations looked like the kind you might see on fantasy and science fiction novels – no surprise, since many of the pieces originally did appear on novels).

Ian Livingstone's editorial references an unnamed survey of unit sales of RPGs in the USA. According to this survey, the ten top selling games are, in order: D&D, AD&D, Traveller, The Fantasy Trip, Top Secret, Chivalry & Sorcery, Tunnels & Trolls, RuneQuest, Space Opera, and Arduin Grimoire. Quite the list, isn't it? I'm not at all surprised to see both D&D and AD&D there; the same goes for Traveller. With the exception RuneQuest and perhaps Tunnels & Trolls, I wouldn't have expected any of the others to be on the list at all, never mind in the top ten.

"The Necromancer" is a new AD&D character class by Lewis Pulsipher. The class is interesting in two respects. The first is that it's limited only to evil aligned characters, much like the assassin (or the death master). The second is that it's not, strictly speaking, a sub-class of magic-user but is instead a unique class all its own. Consequently, it doesn't have spells but "abilities," rated according to "grades," ranked from 1 to 5. Many of these reproduce the effects of certain existing spells (e.g. animated dead, feign death, speak with dead, etc.) but the majority of them are original and focus on the creation and control of undead beings. The class is distinctive and well done and would work well as the basis for an antagonist. I'm not so sure I'd allow its use for a player character, but then I long ago lost the taste for evil PCs.

"... We Have a Referee Malfunction" by Bob McWilliams is a short, humorous article about how a Traveller referee should handle situations that don't go as planned in a session. While it's clearly satirical in purpose, McWilliams nevertheless presents some genuinely useful ideas in the article. "Green Horizon" by Marcus L. Rowland is a stand-alone Traveller scenario in which the players take on the roles of alien beings – the Ksiffchi – whose ship misjumps and winds up in orbit around a primitive planet. Due to the misjump, the ship is damaged and the crew of the vessel have no choice but to land on the planet and attempt to find the parts they require to effect the repairs. The twist is that the primitive world is, in fact, Earth and the Ksiffchi have arrived in June 1944. If you've ever wanted to play a sci-fi adventure where marsupial-like aliens face off against Nazis, "Green Horizon" is for you.

"Open Box" starts its reviews with the Games Workshop boardgame of Judge Dredd (9 out of 10). Next up are five different TSR modules for D&D and AD&D: The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh (9 out of 10), The Secret of Bone Hill (8 out of 10), Against the Giants (10 out of 10), Palace of the Silver Princess (10 out of 10), and Castle Amber (6 out of 10). As you can see, it's both an odd collection of modules and an odd array of ratings. I'm particularly baffled by the high rating of Palace of the Silver Princess, which, while it has much to recommend it, is not even close to being in the same category as the Giants modules. Likewise, I take some offense at the mediocre rating of Castle Amber, but I readily admit my affection for the things probably blinds me to some of its flaws. Finally, there's a review of Chaosium's Borderlands, which receives a 10 out of 10.

"Lashing Out" by Phil Masters is a surprisingly long article on introducing whips into Dungeons & Dragons. In addition to ordinary whips, Masters also presents multiple magical whips, some of which have unusual effects (like the whip of lightning). "Weapon Quest" by Andrew Brice offers up multiple new weapons for use with RuneQuest. Part II of Lewis Pulsipher's "A Guide to Dungeon Mastering" tackles the subjects of "Monsters & Magic." This encompasses not just the choice and placement of monsters and magic items in a dungeon, but also the use of magic and magic items by monsters. As with its predecessor, the advice is solid for it time, but, from the vantage point of 2022, there's hardly anything here I've not before.

"Lord of Kanuu" by John R. Gordon presents a new monster – the spidron – and a mini-scenario in which to use it. The spidron is a malignant green liquid that can disguise itself under a robe to appear as if it is a humanoid being. Instead of being silly, it's strangely creepy, partly, I think, because of the spidron's use of drugs to create zombie-like minions from ordinary people. The author says that he was inspired by an episode of the television show The Tomorrow People. Never having seen the show (that I can recall), I wonder if any readers who have might be able to identify the story that inspired him.

Aside from "The Necromancer" (about which I nevertheless have some issues), issue #35 doesn't stand out in my opinion. It's not a bad issue by any means, but it doesn't quite rise above the level of "workmanlike." That's no criticism. It's difficult to produce exceptional material on a monthly basis; the fact that it ever happens is, frankly, remarkable.

April 25, 2022

Supra-Sentinels

Does anyone remember this Judges Guild advertisement? It appeared in issue #80 (December 1983) of Dragon.

A quick search online reveals that the game was never released, owing to the financial troubles of Judges Guild in the mid-1980s. As a connoisseur of unreleased RPGs, I'm genuinely curious what the game would have been like, both rules-wise and in terms of presentation. JG products were always quite cheaply made but they often overcame these physical flaws but packing a lot of creativity into their newsprint pages. Of course, it's one thing to produce supplements or adventures for someone else's roleplaying games and another entirely to publish your own. I suspect Supra-Sentinels wouldn't have got much traction compared to games like Champions or the soon-to-be-released

Marvel Superheroes

, but who knows?

A quick search online reveals that the game was never released, owing to the financial troubles of Judges Guild in the mid-1980s. As a connoisseur of unreleased RPGs, I'm genuinely curious what the game would have been like, both rules-wise and in terms of presentation. JG products were always quite cheaply made but they often overcame these physical flaws but packing a lot of creativity into their newsprint pages. Of course, it's one thing to produce supplements or adventures for someone else's roleplaying games and another entirely to publish your own. I suspect Supra-Sentinels wouldn't have got much traction compared to games like Champions or the soon-to-be-released

Marvel Superheroes

, but who knows?

A Step Beyond Dungeons & Dragons

From issue #80 of Dragon (December 1983):

Fond though I am of

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain

, I'm having a hard time understanding the sense in which the Fighting Fantasy gamebooks are "a step beyond Dungeons & Dragons." I had a lot of fun with these books. They were a great diversion when I wasn't able to get together with my friends for one reason or another. However, much like the Choose Your Own Adventure books that preceded them, there were inherent limitations to the range of choices available in any gamebook, no matter how well written. For what it's worth, I feel the same way about computer roleplaying games, which are vastly more sophisticated than gamebooks. Even at their best, they cannot compare to the freedom available to players in traditional tabletop RPGs.

Fond though I am of

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain

, I'm having a hard time understanding the sense in which the Fighting Fantasy gamebooks are "a step beyond Dungeons & Dragons." I had a lot of fun with these books. They were a great diversion when I wasn't able to get together with my friends for one reason or another. However, much like the Choose Your Own Adventure books that preceded them, there were inherent limitations to the range of choices available in any gamebook, no matter how well written. For what it's worth, I feel the same way about computer roleplaying games, which are vastly more sophisticated than gamebooks. Even at their best, they cannot compare to the freedom available to players in traditional tabletop RPGs.James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers