James Maliszewski's Blog, page 103

August 12, 2022

Sage Smackdown

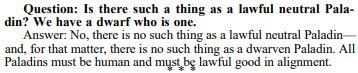

The "Sage Advice" column of Dragon was often of interest to me in my youth, largely because I wanted to know the "right" way to interpret the rules of D&D and (especially) AD&D. While Jean Wells acted as the magazine's Sage, there was a certain semantic bluntness to many of her replies. Take, for example, this one from issue #39 (July 1980):

Wells minces no words about the fact that, in Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, there is no such thing as either a lawful neutral or a dwarf paladin. How could she say otherwise? The entire purpose of the "Sage Advice" column was to present the "official" answer to readers' questions and that's the official answer. If you wish to play AD&D by the book, as Gygax intended, you don't allow either lawful neutral or dwarf paladins in your campaign. End of story.

Of course, that raises another question: do you wish to play AD&D by the book? In my experience, not many people did, mostly out of an unwillingness to be bound by each and every rule presented in the rulebooks, some of which were, I don't think it can be denied, difficult to understand. I know it's popular in some circles to suggest that AD&D simply cannot be played "by the book," should one be desirous to do so. I don't think that's true at all, though, as I said, I rarely encountered instances of it. Even now, I suspect it's quite uncommon among all but the most dedicated referees and players.

I don't see this as good or bad one way or the other. I think there are benefits and drawbacks of strict "by the book" play, just as there are benefits and drawbacks of more flexible (for lack of a better word) approaches to the game. Mind you, I am temperamentally much better suited to the "non-game" of Original D&D than the highly structured baroqueness of AD&D, so perhaps I am not fit to judge the matter. I can only say that, while my younger self, cared deeply about playing the game the "right" way, nowadays, I care more about playing it my way.

August 11, 2022

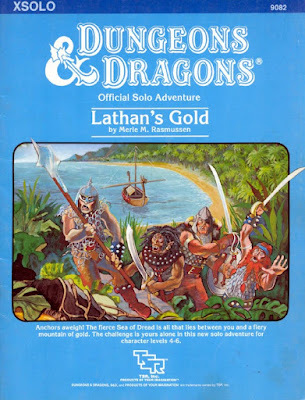

Retrospective: Lathan's Gold

Lately, I've found myself strangely interested in historical attempts by game companies to produce solo or small-group roleplaying adventures. This is a field pioneered by Tunnels & Trolls, whose Buffalo Castle is, I think, the first example of a "solitaire dungeon" in the hobby. (If I am mistaken in this surmise, I am sure my readers will let me know in the comments.) Other companies followed suit, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, in the following years. However, I don't think it was until the success of the Fighting Fantasy series – which I suspect was very successful indeed – that TSR put much effort into solo gaming and, even then, the approach was scattershot and frequently gimmicky.

Lately, I've found myself strangely interested in historical attempts by game companies to produce solo or small-group roleplaying adventures. This is a field pioneered by Tunnels & Trolls, whose Buffalo Castle is, I think, the first example of a "solitaire dungeon" in the hobby. (If I am mistaken in this surmise, I am sure my readers will let me know in the comments.) Other companies followed suit, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, in the following years. However, I don't think it was until the success of the Fighting Fantasy series – which I suspect was very successful indeed – that TSR put much effort into solo gaming and, even then, the approach was scattershot and frequently gimmicky.

One of the better examples of TSR's forays into this market is 1984's Lathan's Gold, written by Merle M. Rasmussen. Rasmussen is perhaps best known for having designed Top Secret, but it's worth noting that, in the very same year as Lathan's Gold, he also penned Midnight on Dagger Alley, another solo adventure, albeit employing a rather different approach. In fact, Lathan's Gold evinces a rather different approach in a number of areas, which might explain why I think much more highly of this solitaire module than I do of others of its kind, as I'll explain.

One of my biggest complaints about previous TSR solo modules is that they're quite limited when it comes to the types of characters one can play. In most cases, they're limited to a single, pre-generated character or several characters that are all fairly similar to one another. Lathan's Gold, conversely, gives the player the choice of six characters, each one of a different class: elf, dwarf, cleric, fighter, magic-user, and thief – all that's missing is a halfling. This might seem like a small thing, but it's not, especially when one considers that several of these characters are spellcasters, something for which I don't believe any previous solo modules made allowances. Consequently, Lathan's Gold feels a bit more "open," even if, of necessity, the range of choices is still very restricted when compared to a "normal" Dungeons & Dragons module.

Related to this is the fact that each character has his own quest, which the player uses to guide his choices. For example, the elf Lathan, after whom the module is named, is on a quest to raise 1000 gp to pay the ransom of his betrothed. Meanwhile, Suparjo the magic-user is on a quest to find a rare seven-headed hydra and Krag Skraddle the thief is seeking a buried pirate's treasure. The other four character each have unique goals as well. All these goals have time limits placed upon them, ranging from about 20 to 90 days. To "win" while playing a particular character, the player needs to succeed in his character's quest within the given timeframe. That's yet another way in which Lathan's Gold differentiates itself from other solitaire modules.

Like the Fighting Fantasy books (or Choose Your Own Adventure books), Lathan's Gold is presented as a series of numbered sections. As a character proceeds through the module, the player turns from section to section, each one describing the situation as it unfolds. In doing so, the player makes use of an "expedition record sheet." The sheet tracks your character's hit points, money, and rations, as well as the number of days that have passed. This is a rare example of a published module where the passage of time plays a central role to a character's ultimate success. It's a genuinely remarkable thing.

Also remarkable is the module's alternate combat system. Rather than having the player play out every combat between his character – and his hirelings; yes, you can bring along hirelings – and any opponents he might encounter, Rasmussen has devised a simpler way to determine the results of a fight. The player compares the number, level/hit dice, and armor classes of those engaged in a fight and then rolls on a few tables to find the outcome. The tables remind me quite a bit of those used in hex-and-chit wargames. Some might find them less satisfying than "real" D&D combat, but I find they work quite well in the context of a solitaire adventure, where the player has to handle all aspects of gameplay. Obviously, opinions will vary on this front.

Lathan's Gold is not a highly detailed adventure. Rather, it's a collection of procedures for handling a character's journey in urban environments, on the seas, and on one or more mysterious islands in the seas. These procedures are quite expansive in their available options, especially when compared to most solitaire adventures, but they're sketchy at times, leaving a lot to the imagination of the player. That's the price for the openness I mentioned earlier. Unless the module for many times larger than it is, I don't see any way that it could be anything but somewhat skeletonic in its presentation. Ultimately, I'm not sure Lathan's Gold fully succeeds in its goals. Even so, it's much better than I remembered its being and far better than TSR's other experiments with solo adventures.

August 9, 2022

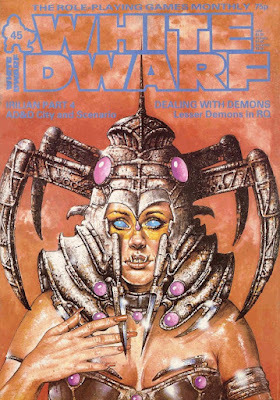

White Dwarf: Issue #45

Issue #45 of White Dwarf (September 1983), featuring a very weird cover by Gary Ward, is an important one in the history of the magazine, at least for me. First, this issue marks the premier of two new comic strips, both of which are very dear to me. Ian Livingstone would seem to agree, since he uses his editorial to announce this fact and urges readers to give the new comics "a chance to settle in." I gather from his comments that not all readers like comics in their gaming magazines, which is understandable, as gaming comics tend to be very hit or miss (mostly the latter, in my experience). Second, this issue also marks the appearance of the very first battle scenario for Warhammer in the pages of White Dwarf. It is an omen for things to come.

Issue #45 of White Dwarf (September 1983), featuring a very weird cover by Gary Ward, is an important one in the history of the magazine, at least for me. First, this issue marks the premier of two new comic strips, both of which are very dear to me. Ian Livingstone would seem to agree, since he uses his editorial to announce this fact and urges readers to give the new comics "a chance to settle in." I gather from his comments that not all readers like comics in their gaming magazines, which is understandable, as gaming comics tend to be very hit or miss (mostly the latter, in my experience). Second, this issue also marks the appearance of the very first battle scenario for Warhammer in the pages of White Dwarf. It is an omen for things to come.The issue kicks off with "Open Box," which reviews Avalon Hill's Wizards. This is a game I regularly saw in game stores but never owned or played. The reviewer, Alan E. Paull, found its presentation somewhat frustration, but liked its gameplay enough to give it 7 out of 10. Meanwhile, Oliver Dickinson gives Pavis 9 out of 10, which is, I think, a little stingy. The older I get, the more I have come to appreciate the output of Chaosium in the late '70s and early '80s, with Pavis and Big Rubble among its masterpieces. Also reviewed are three modules for AD&D and one for D&D: Tomb of the Lizard King (9 out of 10), Pharaoh (10 out of 10), Oasis of the White Palm (10 out of 10), and Blizzard Pass (6 out of 10) respectively. With the exception of Blizzard Pass, I think these ratings are a bit generous, but tastes differ, of course, and I recall thinking much better of the "Desert of Desolation" series at the time than I do now.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" spends most of its space on a lengthy review of C.J. Cherryh's Downbelow Station, which was the winner of the previous year's Hugo Award for best novel (for what it's worth). Langford seems genuinely well disposed toward Cherryh as a writer, but doesn't think this is her best effort. He also does quick reviews of three other books, including Italo Calvino's If On a Winter's Night a Traveler, which is an admittedly strange book to review in White Dwarf, though "Critical Mass" frequently devoted itself to books other than those that could easily be called fantasy or science fiction.

Part 2 of Dave Morris's "Dealing with Demons" focuses on lesser demons, describing them and their abilities for use with RuneQuest. The article's main attraction, in my opinion, is that these demons are (mostly) original rather than drawing on real world myths and legends. It's a clever approach to the topic, I think, though they're a good fit for RQ's Glorantha setting is another matter (assuming that was the intention, since the article is silent on the matter). "Gateway to Adventure" by Bob McWilliams is a "cameo" adventure, which is a coinage of McWilliams for "small scenes or themes that could be fitted into an ongoing campaign." In this case, the cameo is about researching an interplanetary transport device – the titular Gateway – that leads somewhere else. McWilliams doesn't provide any information on what's beyond the gate, leaving that to the referee to decide, which is admittedly a little unsatisfying. On the other hand, the set-up is fairly good and it's an unusual one for Traveller, which is a plus.

"Stop, Thief!!" by Marcus L. Rowland is a short article detailing the contents, along with individual weight and costs, of the items in a typical thieves' kit. I personally don't care for this level of detail, but I can appreciate its utility in certain circumstances. Part 4 of Daniel Collerton's "Irilian" is as good as its predecessors. In addition to the usual mix of local businesses, this installment describes the town's guards, bureaucracy, and ruling council. It's packed with the kind of detail that a referee needs if he intends to use a town as regular locale for his campaign. There's also an adventure set in the town relating to religious corruption and false relics – good stuff!

As I mentioned earlier, this issue marks the debuts of two new comic strips. The first is Thrud the Barbarian by Carl Critchlow. Thrud is a delightful parody of Conan and his mighty-thewed knock-offs. Most of Thrud's adventures involve random mayhem and destruction as a result of his penchant for attacking first and then thinking later, if at all. I'm especially fond of his encounter with an Elric clone, but most of his stories are great. Also premiering in this issue is Mark Harrison's The Travellers, which is a similarly broad parody of science fiction, filtered through the lens of GDW's Traveller. If anything, it's even more delightful than Thrud and I simply adored it back in the day (and still do).

"Divinations" by Oliver Dickinson is largely a collection of errata and clarifications to RuneQuest and RQ products. As such, it's only of interest to diehard fans. "Thistlewood" is a Warhammer Fantasy Battles scenario intended for two, four, or six players, plus an umpire. The scenario is a fairly typical "defend a sleepy little village against invaders" kind of thing, but it's filled with lots of charming details and information from the early days of Warhammer, before it became the behemoth of later years, so I find it strangely compelling nonetheless. Of particular note is the fact that the scenario is written by Joe Dever, best known for his work on the Lone Wolf series of gamebooks.

"Fiend Factory" offers up four new elemental monsters for use with D&D and AD&D. The somewhat misnamed "Elemental Items" by Daniel Hooke is actually a collection of eight new magic items that pertain to the para-elemental planes. Finally, "Super Mole" is a gossip column about the RPG industry, written by an anonymous author, after the fashion of Gigi D'Arne of Different Worlds but without the bitchiness. Most of the gossip is ephemeral stuff that has little lasting value, but I did find the section relating to Chaosium and its licensing of RuneQuest to Avalon Hill fascinating. According to Super Mole, Greg Stafford stated that the Chaosium crew simply wanted to design games and had no interest in "printing, selling, credit control," and the more tedious, business-related aspects of producing RPG materials. This is something I've long suspected to be the case (and indeed may have read somewhere else), but it's fascinating to see it stated here so baldly.

Issue #45 is another solid one. White Dwarf has really hit its stride in my opinion, though I am undoubtedly biased, since I'm now well into the run of issues with which I am most familiar. We're not quite yet at the point when I was a regular subscriber, though that will come soon and I'm rather excited to revisit those particular issues. In the meantime, though, I continue to enjoy these revisits to one of the truly great magazine's of our hobby.

August 8, 2022

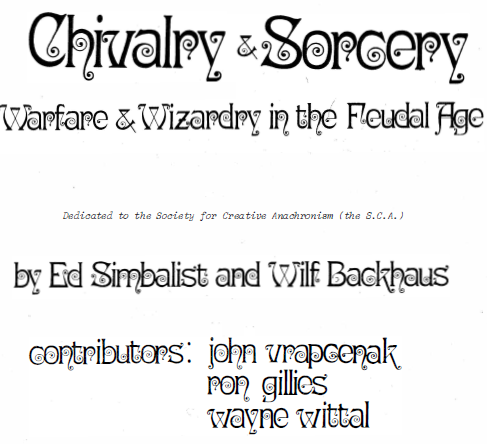

Dedications

I'd like to offer my thanks to Rob Conley, who pointed out that the title page of the first edition of FGU's Chivalry & Sorcery includes a dedication by the authors to the Society for Creative Anachronism (S.C.A.). The role of the SCA in the history of fantasy fandom (and, by extension, roleplaying games) is still underappreciated, I think. Since I've never been a member or attended any of the Society's events (though my college roommate went to Pennsic every summer), this is a topic about which I know very little. I'd love to know more about it, though, especially as it relates to the influence it may have had over the early days of the hobby.

Fantasy Realism!

I love looking at old advertisements of all kinds, but especially for roleplaying games. Here's a great one for RuneQuest, which appeared in issue #40 of Dragon (August 1980).

I want to take a look at each paragraph of the ad, because I think each one includes some fascinating boasts about RQ. Before doing that, though, I simply want to draw attention to the ad's title, which plays off a very common concern in the hobby during the early to mid-1980s – realism. This is a topic that gets a lot of coverage in the RPG magazines of the era, including Dragon, and one about which I have opinions of my own. Those aside, what interests me most about this particular case is the way that Chaosium frames the question of "realism" beyond simply having a high degree of verisimilitude in its combat system (though that is part of their pitch).

I want to take a look at each paragraph of the ad, because I think each one includes some fascinating boasts about RQ. Before doing that, though, I simply want to draw attention to the ad's title, which plays off a very common concern in the hobby during the early to mid-1980s – realism. This is a topic that gets a lot of coverage in the RPG magazines of the era, including Dragon, and one about which I have opinions of my own. Those aside, what interests me most about this particular case is the way that Chaosium frames the question of "realism" beyond simply having a high degree of verisimilitude in its combat system (though that is part of their pitch).

This is genuinely remarkable. I can't say with any certainty that this is the first time that a RPG company has claimed that one of its games allows players to "legitimately simulat[e] the great dramas of fantasy," but it's not a boast I recall being made often. I don't believe any TSR edition of Dungeons & Dragons ever made such a claim, even AD&D 2e, which is frequently derided as the "Ren Faire" edition of D&D by grognards more cantankerous than I. It's also worth noting that the ad goes on to state that RuneQuest's "technically-accurate role-playing mechanics" are "not merely collected encounter and resolution systems." That suggests, at the very least, Chaosium believed that RQ had achieved something genuinely new and indeed different from its predecessors and competitors. Does this make RuneQuest the first storytelling game, at least in its own self-conception?

This is genuinely remarkable. I can't say with any certainty that this is the first time that a RPG company has claimed that one of its games allows players to "legitimately simulat[e] the great dramas of fantasy," but it's not a boast I recall being made often. I don't believe any TSR edition of Dungeons & Dragons ever made such a claim, even AD&D 2e, which is frequently derided as the "Ren Faire" edition of D&D by grognards more cantankerous than I. It's also worth noting that the ad goes on to state that RuneQuest's "technically-accurate role-playing mechanics" are "not merely collected encounter and resolution systems." That suggests, at the very least, Chaosium believed that RQ had achieved something genuinely new and indeed different from its predecessors and competitors. Does this make RuneQuest the first storytelling game, at least in its own self-conception?

That having been said, Chaosium is nevertheless quick to point out how realistic its combat system is. The fact that its combat system was "created by a charter member of the Society for Creative Anachronism" – this is a reference to Steve Perrin, who joined the SCA at its inception in 1966 – is highlighted. Even in my youth, it was commonplace to knock D&D for its "unrealistic" combat system with those of other RPGs being held up as examples of better design in this regard. Because of my own prejudices, I wasn't very familiar with RQ at the time, so I can't recall its being cited as one of these putatively realistic games, but, based on this advertisement, Chaosium apparently thought it was.

That having been said, Chaosium is nevertheless quick to point out how realistic its combat system is. The fact that its combat system was "created by a charter member of the Society for Creative Anachronism" – this is a reference to Steve Perrin, who joined the SCA at its inception in 1966 – is highlighted. Even in my youth, it was commonplace to knock D&D for its "unrealistic" combat system with those of other RPGs being held up as examples of better design in this regard. Because of my own prejudices, I wasn't very familiar with RQ at the time, so I can't recall its being cited as one of these putatively realistic games, but, based on this advertisement, Chaosium apparently thought it was.

"Practitioners of real magic?" Even given that, at the time, Chaosium was a California-based company, this is a bizarre statement. Were I to suspend my natural skepticism, the larger point remains that I can't detect much in the way of "real magic" in the magic systems of RuneQuest. They strike me as artifacts of game design – good design, to be fair – but they don't seem to have much in common with any historical systems of magic with which I am familiar. Perhaps my education is simply lacking. On the other hand, I do think RQ deserves credit for making religion and religious beliefs much more significant in play than, say, D&D does. Whether this is the result of RQ's having been "patiently assembled by scholars and practitioners of … the Old Religion" I leave to others to determine.

"Practitioners of real magic?" Even given that, at the time, Chaosium was a California-based company, this is a bizarre statement. Were I to suspend my natural skepticism, the larger point remains that I can't detect much in the way of "real magic" in the magic systems of RuneQuest. They strike me as artifacts of game design – good design, to be fair – but they don't seem to have much in common with any historical systems of magic with which I am familiar. Perhaps my education is simply lacking. On the other hand, I do think RQ deserves credit for making religion and religious beliefs much more significant in play than, say, D&D does. Whether this is the result of RQ's having been "patiently assembled by scholars and practitioners of … the Old Religion" I leave to others to determine.

What I find most notable here is that Chaosium wishes to draw attention to the fact that RuneQuest takes inspiration from "all the faces of fantasy," not merely those drawing on medieval European history and legend. As a fan of Tékumel, I very much appreciate fantasy settings that draw on other sources of inspiration than the European Middle Ages. Glorantha does borrow from European history and legend, though that's mostly of a pre-medieval kind, such as the Heroic and Classical Ages of the Mediterranean. It also takes a lot from the Near and Middle East, so this isn't a boast that's wholly without merit. I mostly find it fascinating that Chaosium chose to boast about this in the ad. I think it speaks to what was going on in the wider RPG scene at the time.

What I find most notable here is that Chaosium wishes to draw attention to the fact that RuneQuest takes inspiration from "all the faces of fantasy," not merely those drawing on medieval European history and legend. As a fan of Tékumel, I very much appreciate fantasy settings that draw on other sources of inspiration than the European Middle Ages. Glorantha does borrow from European history and legend, though that's mostly of a pre-medieval kind, such as the Heroic and Classical Ages of the Mediterranean. It also takes a lot from the Near and Middle East, so this isn't a boast that's wholly without merit. I mostly find it fascinating that Chaosium chose to boast about this in the ad. I think it speaks to what was going on in the wider RPG scene at the time.In any case, I thought this advertisement was well worth sharing. It's a compelling historical document of the hobby from just six years after the publication of OD&D. In just a few short paragraphs, the ad reveals a lot about the state of RPG design at the time, as well as the larger concerns within the hobby about what constituted "good" rules and setting design.

August 7, 2022

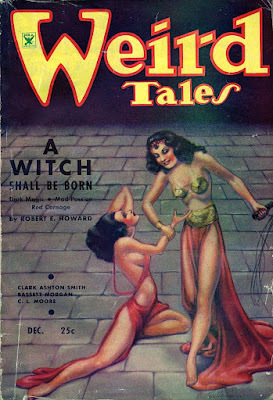

Pulp Fantasy Library: A Witch Shall Be Born

Like many who made his living writing for the pulps, Robert E. Howard (and his most famous creation, Conan the Cimmerian) is easy to reduce to a caricature. I can certainly understand why this is the case. Not all of Howard's stories are of equal quality and, even leaving aside a handful downright stinkers – "Vale of the Lost Women," I'm looking at you – there's often a degree of sameness to many of his yarns. Even at his worst, though, REH frequently has a lot to offer. Indeed, I feel he doesn't always get enough credit for his willingness to try out different styles and approaches, not to mention content, in his established series.

Like many who made his living writing for the pulps, Robert E. Howard (and his most famous creation, Conan the Cimmerian) is easy to reduce to a caricature. I can certainly understand why this is the case. Not all of Howard's stories are of equal quality and, even leaving aside a handful downright stinkers – "Vale of the Lost Women," I'm looking at you – there's often a degree of sameness to many of his yarns. Even at his worst, though, REH frequently has a lot to offer. Indeed, I feel he doesn't always get enough credit for his willingness to try out different styles and approaches, not to mention content, in his established series.I thought of this fact as I re-read "A Witch Shall Be Born," which first appeared in the December 1934 issue of Weird Tales. Critics of Conan generally consider this story middling at best, while some judge it more harshly. Even those who think better of it largely do so because it contains perhaps the most memorable scenes in all of the Cimmerian's adventures: Conan's crucifixion – a scene so unforgettable that it was included in the 1982 John Milius film, albeit in a very different context.

Again, I can certainly understand this perspective. "A Witch Shall Be Born" is no "Red Nails" or Hour of the Dragon; it's not even "The Pool of the Black One." At the same time, I genuinely feel as if Howard was attempting to do something different with this story. For example, a lot of the story's actions focuses on characters other than Conan – in particular, two women: Taramis and Salome. It's almost as if Howard knew that Conan was such a draw for Weird Tales that he had sufficient leeway with its notoriously demanding editor, Farnsworth Wright, to experiment with his own proven formula. Whether he succeeded or not is a question for each reader, though I personally feel as if "A Witch Shall Be Born," while a lesser Conan tale, is nevertheless a worthy one.

The story begins as Taramis, Queen of Khauran, awakens from her sleep to see a figure standing over her bed:

In a sudden panic the queen opened her lips to cry out for her maids; then she checked herself. The glow was more lurid, the head more vividly limned. It was a woman's head, small, delicately molded, superbly poised, with a high-piled mass of lustrous black hair. The face grew distinct as she stared—and it was the sight of this face which froze the cry in Taramis's throat. The features were her own! She might have been looking into a mirror which subtly altered her reflection, lending it a tigerish gleam of eye, a vindictive curl of lip.

"Ishtar!" gasped Taramis. "I am bewitched!"

Appallingly, the apparition spoke, and its voice was like honeyed venom.

"Bewitched? No, sweet sister! Here is no sorcery."

"Sister?" stammered the bewildered girl. "I have no sister."

"You never had a sister?" came the sweet, poisonously mocking voice. "Never a twin sister whose flesh was as soft as yours to caress or hurt?"

"Why, once I had a sister," answered Taramis, still convinced that she was in the grip of some sort of nightmare. "But she died."

As the text suggests, the figure is in fact Salome, the twin sister of the queen. From birth, Salome bore the mark of being a witch – "a scarlet half-moon between her breasts" – and, for this reason, she was left exposed in the desert to die, lest disaster befall the kingdom. Rather than dying, she was found by a magician "from far Khitai," who raised her and taught her his "black wisdom." Now, Salome has returned to Khauran to fulfill her destiny by taking the place of her twin sister and ruling in her place.

In this, Salome has the aid of Constantius, a foreign mercenary commander whose army Taramis had allowed to cross her borders on the way to other lands. Once Salome has assumed the identity of Taramis – the real Taramis being thrown into the palace dungeon – she makes Constantius her consort and places his mercenaries in charge of the realm's defense. This sudden turn of events does not sit well with the queen's captain of the guard, Conan the Cimmerian.

Purely from a narrative perspective, it's fascinating that Howard has other people talk about Conan before he actually appears in the story himself. Conan's suspicion of the orders given by Salome-as-Taramis and his subsequent battle against the soldiers of Constantius isn't something we see firsthand. Instead, we hear others describe these events and their reactions to them. This is what I meant above when I suggested that Howard was experimenting with this story. In it, Conan almost appears as a legend, a larger-than-life figure of rumor and tall tales, as if Howard was slyly offering commentary on the popularity of his own creation.

Despite his great strength and skill in battle, Conan was eventually overcome by Constantius' men, who capture him and then cart him out to the desert, where he is to be crucified for his defiance. Being a barbarian, Conan is loyal to the real queen Taramis, the woman to whom he had sworn an oath of allegiance and nothing, not even the threat of death by crucifixion, is enough to make him foreswear that loyalty. This is an important theme within "A Witch Shall Be Born," along with Howard's perennial musings on the relative merits of civilization and barbarism.

Before leaving him to die, Constantius mocks Conan.

"I am sorry, captain," he said, "that I cannot remain to ease your last hours, but I have duties to perform in yonder city—I must not keep your delicious queen waiting!" He laughed softly. "So I leave you to your own devices—and those beauties!" He pointed meaningly at the black shadows which swept incessantly back and forth, high above.

"Were it not for them, I imagine that a powerful brute like yourself should live on the cross for days. Do not cherish any illusions of rescue because I am leaving you unguarded. I have had it proclaimed that anyone seeking to take your body, living or dead, from the cross, will be flayed alive together with all the members of his family, in the public square. I am so firmly established in Khauran that my order is as good as a regiment of guardsmen. I am leaving no guard, because the vultures will not approach as long as anyone is near, and I do not wish them to feel any constraint. That is also why I brought you so far from the city. These desert vultures approach the walls no closer than this spot.

"And so, brave captain, farewell! I will remember you when, in an hour, Taramis lies in my arms."

Astute readers might well see a parallel between Conan's abandonment to die in the desert and that of Salome, the twin of the queen whom Conan serves. Like Salome, Conan does not die in the desert but instead escapes the fate intended for him to forge his own destiny, namely the defeat of those who tried to slay him and who have usurped Taramis through deceit.

While "A Witch Shall Be Born" is far from a masterpiece, it has much to recommend it. In addition to the stylistic experimentation I mentioned earlier, it's also a fast-paced story of loyalty and revenge, two favorite themes of Howard's fiction. Further, the story touches on the themes of identity and duality, as exemplified by the twin sisters who advance much of the tale's actions, not to mention the theme of personal destiny. The result is a fairly satisfying story that I think catches more flak from Conan fans than it deserves. This is, in my opinion, a story that's much better than its reputation and well worth a read.

August 4, 2022

"Let's See What's Behind ..."

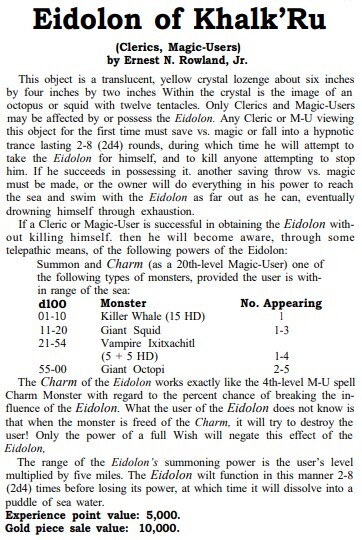

The Greater-than-Gods

Gary Gygax was a great admirer of the works of A. Merritt, highlighting several of his works for particular mention in his Appendix N. One of these is The Dwellers in the Mirage. The story was first published as a serial in Argosy in early 1932 before being its installments were collected together into a novel later that same year. Among other things, Dwellers is notable for including an homage to Lovecraft in the form of Khalk'ru the Kraken, an ancient octopoid entity similar to Cthulhu.

While Merritt and his works are largely unknown to most fantasy fans these days, that wasn't the case back in the earliest days of the hobby. Issue #45 of Dragon (January 1981) included the following entry in the magazine's "Bazaar of the Bizarre" column, inspired by The Dwellers of the Mirage.

August 3, 2022

Grognard's Grimoire: Ven Mor

A ven mor by Zhu BajieIn the Thirty-Second Year of the Sixth Cycle, a strange affliction appeared in Rayaldama. Dubbed the Curse of the Makers, it is magical in nature. Its first victims were adventurers who had entered Rayaldama's Vaults, contrary to the Everlasting Edicts of Akamra. The Curse's first symptom is high fever, followed by violent madness, and finally unconsciousness, during which time the victim's body rapidly transforms into that of a bestial humanoid. Those so transformed retain little of their former identities. Instead, they are consumed by a desire to kill and spread the pestilence that afflicts them to others, thereby propagating their kind.

A ven mor by Zhu BajieIn the Thirty-Second Year of the Sixth Cycle, a strange affliction appeared in Rayaldama. Dubbed the Curse of the Makers, it is magical in nature. Its first victims were adventurers who had entered Rayaldama's Vaults, contrary to the Everlasting Edicts of Akamra. The Curse's first symptom is high fever, followed by violent madness, and finally unconsciousness, during which time the victim's body rapidly transforms into that of a bestial humanoid. Those so transformed retain little of their former identities. Instead, they are consumed by a desire to kill and spread the pestilence that afflicts them to others, thereby propagating their kind.The physical manifestation of the Curse varies from victim to victim; there is no single "standard" appearance of a ven mor. Some sages suggest a connection between the last meal of animal matter consumed by the afflicted and his bestial transformation, while others scoff at this as superstition. True or not, the peasantry of Inba Iro and surrounding lands long ago adopted a vegetarian diet as a precaution against the Curse. An outbreak of the Curse in civilized lands is thus a serious threat and no effort is spared to contain it by starving it of potential hosts.

AC 5 [14], HD 2* (9hp), Att 1 × weapon (1d6 or by weapon), THAC0 18 [+1], MV 120’ (40’), SV D12 V13 P14 B15 S16 (2), ML 10, XP 25 (narahan: 50), NA 2d4 (1d6 × 10), TT D

Weapons: Prefer clubs and other blunt weapons. Curse of the Makers: At the beginning and end of any melee combat with one or more ven mor, save versus poison with a +2 bonus. Those who fail both rolls transform into a beast man after an illness of 1d4 days. There is no known cure, though rumors persist that the priests of Ukol possess a spell to counteract it.Narahan: Groups of 20+ are led by a more powerful ven mor (called a narahan) with 3HD (16hp). Another ven mor

Another ven mor

Maximum and Ideal Party Size

In light of the discussion in the comments to this post, I find myself wondering about readers' experiences with party size in their play of various RPGs over the years. In particular, I'm curious about both the maximum number of players with whom one has ever played successfully and what one considers the ideal number of players. I realize that one's ideal size might vary from game to game. A game like Dungeons & Dragons is much easier to run with a large number of characters, while one like Top Secret probably has a smaller number of ideal players. Nevertheless, I think most of us who've gamed for a long time has a general sense of what works best and I'd like to hear about it in the comments.

For myself, the largest group I've ever played with successfully consisted of ten or eleven players. This was a D&D game and the players were surprisingly well organized in their actions and ability to communicate it to me as the referee. That was the exception rather than the rule, though. Most of the successful games I've played in since have had probably half that number, which may explain why I tend to consider five to seven players to be ideal in most circumstances.

What about yourself?

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers