James Maliszewski's Blog, page 99

September 23, 2022

Half-Orcs Were a Mistake

Wanted: For the Crime of

Wanted: For the Crime of Gygaxian Naturalism

Despite Gary Gygax's repeated assertion that his conception of Dungeons & Dragons owes little to the works of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings (which he nevertheless included in Appendix N), he sure did borrow a lot of individual elements from the novel! Orcs are regularly cited as the prime example of this peculiar phenomenon and rightly so, I think, because, as a distinct type of enemy, they are largely without any significant mythological precedent prior to the publication of Tolkien's tales. At the same time, orcs are, at base, little more than man-shaped monsters in service to Evil, not unlike similar creatures found in northern European folklore and in the pulp fantasy stories that proliferated in the first half of last century.

The same, however, cannot be said for the half-orc, references to which can also be found in The Lord of the Rings. The precise nature of half-orcs in Middle-earth is unclear, partly because I don't believe Tolkien ever settled the question of the nature of orcs, having changed his mind several times on the subject. What we can say for certain is that Tolkien's half-orcs – or "goblin-men," as he sometimes called them – were creatures that, while generally orcish, looked enough like Men that they move among them without attracting much comment. Half-orcs were thus useful as spies by the forces of Evil.

Half-orcs don't exist in Dungeons & Dragons prior to the publication of the AD&D Monster Manual in 1977, where there's a brief discussion of them at the end of the book's entry for "orc." There, Gygax states that

As orcs will breed with anything, there are any number of unsavory mongrels with orcish blood, particularly orc-goblins, orc-hobgoblins, and orc-humans. Orcs cannot cross-breed with elves. Half-orcs tend to favor the orcish strain heavily, so such sorts are basically orcs although they can sometimes (10%) pass themselves off as true creatures of their other stock (goblins, hobgoblins, humans, etc.).

This sounds a lot like the broos of Glorantha, does it not? In any case, the Players Handbook a year later gives us a a bit more information about them. Here, Gygax reiterates that

Orcs are fecund and create many cross-breeds, most of the offspring of such being typically orcish. However, some one-tenth of orc-human mongrels are sufficiently non-orcish to pass for human.

The remainder of the PHB's description is given over to game mechanics, with little else stated about the nature of half-orcs or the place within the implied setting of AD&D. We do learn that, with the exception of humans and halflings (!), all other playable races hate or have antipathy for half-orcs. This makes sense, given half-orcs' preference for classes like thief and assassin, marking them as having criminal and antisocial tendencies of a most unsavory sort. I have no idea why Gygax felt the need to include orc-human hybrids as a playable race in AD&D, though I suspect that, like half-elves, which first appeared in Supplement I to OD&D, he did so to appeal to the fans of The Lord of the Rings among early gamers. I think this was a profound mistake, one that has haunted D&D ever since.

I say this because orcs are monsters. According to the Monster Manual, they "are cruel and hate living things in general." Likewise, "they take slaves for work, food, and entertainment (torture, etc.)." They're not people in the same sense that, say, humans, dwarves, or elves are – or at least that's how I think they were initially conceived. Unfortunately, Gygaxian naturalism upended that particular apple cart and we discovered that orc lairs contain noncombatant females and young. No longer is an expedition into the Caves of Chaos a simple matter of defending the Realm against Evil; now it's an exercise in the mass murder of the defenseless.

The existence of playable half-orcs only complicates the matter further. It might just be possible to squint one's eyes and imagine that even baby orcs are an existential threat to the Realm of Law and Goodness and therefore fit only for extermination. Once you allow playable orc-human hybrid characters who are not required by the rules to evil, let alone restricted from being good, you open the door to viewing orcs (and, by extension, all humanoid monsters) as people on par with the more traditional player character races. From there, you're well on the road out of the adventuresome pulp fantasy world D&D has long evoked and heading toward … something else entirely.

Far be it for me to suggest that there's anything inherently wrong with this approach to fantasy. Indeed, there might well be something genuinely fun and compelling about treating humanoid races as one might treat alien species in an episode of Star Trek rather than as ravening Chaos-spawn that bubble up from the black blood of the Earth to wreak havoc across the Realm of Man. However, for those of us who like fighting orcs (and goblins and gnolls and …) without pangs of conscience, I think it's important we keep them genuinely monstrous and inhuman. Doing this necessitates, among other things, abandoning the idea of playable half-orcs. They were a grave mistake back in 1978 and they've only become more so in the more than four decades since.

September 22, 2022

Apropos of Nothing, I Assure You

Mörk Borg: Disillusioned Templar

A FAITHLESS CLASS

You cast off your old life and took up your mighty sword in defense of the faithful. You thought yourself blessed when your masters judged you worthy to guard the Cathedral in Galgenbeck itself. But soon you saw the truth: the corruption, the decadence, the devilry that lurked within. You renounced your oaths and fled, hounded by the Two-Headed Basilisks for your vile apostasy.

Begins with2d6 × 10s and d3 Omens.

HP: Toughness + d10

Oathbound Name (2d10)Your vows stripped you of your birth name and you cannot reclaim it. The Basilisks dubbed you:

1

First

Austerity

2

Second

Justice

3

Third

Purity

4

Fourth

Rectitude

5

Fifth

Reverence

6

Sixth

Righteousness

7

Seventh

Sanctity

8

Eighth

Temperance

9

Ninth

Truth

10

Tenth

Zeal

What Broke Your Faith (d8):Widespread consulting of blasphemous texts.

Sacrifice of children to Vehru to secure the gift of prophecy.

Torture of innocents for amusement.

Simony: the sale of ecclesiastical offices for riches.

Sexual depravity among the ecclesiarchs.

Daemonic whispers echoing in the halls of the Cathedral.

Murder of a priest to advance the position of another.

Necromantic rituals practiced on the high altar of the Cathedral.

AbilitiesSteadfast, roll 3d6+2 for Toughness. Stolid, roll 3d6–2 for Presence. Roll d4 on the Armor table. Roll d6 to determine which of the following unique Zweihänders you wielded in service to the Two-Headed Basilisks:

Fulgent The blade glows in the presence of undead within 30 feet, but they attack you above all other targets.

Infrangible The blade is unbreakable by any means, even a fumble.

Minatory The blade is frightfully curved, granting +1 to morale rolls against enemies.

Piercing The blade deals +1 damage against tier 0 and tier 1 armor.

Tenacious If broken while wielding the blade, re-roll result of dead; second result of dead is needed to slay you.

Warding While wielding the blade, your defense DR is 11.

The Enduring Appeal of Character Classes

The other day I was looking into a roleplaying game to which I'd recently seen references and was surprised to discover that, despite its having been published in 2022 and not being a fantasy game, it nevertheless made use of character classes. Of course, character classes, like hit points and experience points, to cite just two examples, are well-established elements of RPG design, owing to their having appeared in Dungeons & Dragons at the dawn of the hobby. That even a game published almost a half-century after OD&D makes use of them thus shouldn't be the least bit shocking.

The other day I was looking into a roleplaying game to which I'd recently seen references and was surprised to discover that, despite its having been published in 2022 and not being a fantasy game, it nevertheless made use of character classes. Of course, character classes, like hit points and experience points, to cite just two examples, are well-established elements of RPG design, owing to their having appeared in Dungeons & Dragons at the dawn of the hobby. That even a game published almost a half-century after OD&D makes use of them thus shouldn't be the least bit shocking.

The reason that I was surprised is that, for as long as I've been involved in the hobby, there have been loud complaints about character classes and their supposed deficiencies. One of the commoner complaints is that classes are too "restrictive" in some fashion. Others argue that the classes are "arbitrary" or even "unrealistic" in the way they categorize the skills and abilities of different adventuring professions/vocations. Still others say that classes are "simplistic," a relic of an earlier phase of game design before more "sophisticated" approaches had been imagined. Like training wheels on a bicycle, the hobby should abandon character classes now that it finally understands how to build a better game.

Seeing a new RPG make use of characters would seem to run counter to these long-stated complaints, not all of which are without some merit. Indeed, I have at various times been sympathetic to many of them, particularly those that focus on the limiting nature of character classes. Why shouldn't a fighter be able to learn how to pick locks or climb walls? Why shouldn't a magic-user be able to pick up a sword and fight? This is the line of thought advanced by Chaosium in its early advertisements for RuneQuest, which decried character classes as "artificial" and, on that basis, ought to be rejected in favor of "a realistic set of fantasy rules based on experience and reality rather than an arbitrarily developed abstract mathematical system."

Truth be told, I understand Chaosium's perspective well, especially of late, as my appreciation for the elegance of the design of Basic Role-Playing has increased. As I continue to (slowly) chip away at my Secrets of sha-Arthan setting, I'm seriously considering the abandonment of character classes altogether, opting instead for something much looser and closer to BRP's skill-focused design, since it more closely approximates the kind of weird science fantasy that inspired sha-Arthan in the first place.

Truth be told, I understand Chaosium's perspective well, especially of late, as my appreciation for the elegance of the design of Basic Role-Playing has increased. As I continue to (slowly) chip away at my Secrets of sha-Arthan setting, I'm seriously considering the abandonment of character classes altogether, opting instead for something much looser and closer to BRP's skill-focused design, since it more closely approximates the kind of weird science fantasy that inspired sha-Arthan in the first place.Yet, there can be no denying that character classes, whatever their putative flaws, have stood the test of time. The very simplicity that critics decry is, in fact, one of their virtues. Classes are quite helpful for newcomers, since they narrow the range of choices during character generation to a flavorful handful of easy-to-understand archetypes. In a similar way, their artificial restrictions and limitations help to ensure that every character has a delineated mechanical role. This, too, is important to newcomers, who can sometimes be overwhelmed by the freedom inherent in roleplaying games, where there is no obvious "right" answer to the referee's perennial question of "What would you like to do now?"

Now, to those who've played RPGs for years, particularly those suffering from D&D fatigue, character classes may well seem like a played out concept that's no longer fit for purpose, one that's been superseded by a number of alternative ways to build a player character. I wouldn't dare to deny this, though I would point out that, except for a handful of exceptions – GURPS being one of those with which I have great familiarity – most roleplaying games include some sort of mechanical frame around which a player builds his character, whether it's the prior services of Traveller, the occupations of Call of Cthulhu, or even the clans/tribes/traditions/etc. of White Wolf's World of Darkness games. Some of these alternate approaches are a little more flexible than D&D's character classes certainly, but are they wholly different? (It's worth noting, too, that, like many other elements laid down by D&D, many video games make use of character classes and do so for the very reasons I've outlined here.)

In the final analysis, I think it's fair to say that character classes work. They might not "make sense" according to some lines of thoughts, but they serve the purpose for which they designed, namely to make it relatively easy to generate a character and to give that character a ready-made niche within the play of the game. That's not nothing. Indeed, it's a genuinely clever bit of design that I don't think gets as much praise as it deserves.

September 21, 2022

Retrospective: Beyond

GDW's roleplaying game, Traveller, was first released in the summer of 1977. Given this relatively early date in the history of the hobby, it's no surprise that Traveller's creator, Marc Miller, looked to Dungeons & Dragons as a model for how to present an RPG. An obvious debt that Traveller owes to OD&D is its format: three digest-sized books. Another is that Traveller presents no setting of its own. Like its predecessor, it's a toolkit intended to allow the referee to create a setting of his own using the game's rules and his own imagination.

GDW's roleplaying game, Traveller, was first released in the summer of 1977. Given this relatively early date in the history of the hobby, it's no surprise that Traveller's creator, Marc Miller, looked to Dungeons & Dragons as a model for how to present an RPG. An obvious debt that Traveller owes to OD&D is its format: three digest-sized books. Another is that Traveller presents no setting of its own. Like its predecessor, it's a toolkit intended to allow the referee to create a setting of his own using the game's rules and his own imagination. Nevertheless, the first hints of an "official" setting for Traveller started to appear about a year after the game's publication. Book 4: Mercenary mentions "the Imperium" for the first time, though designer Frank Chadwick's introduction suggests that he intended this name simply to be a convenient placeholder for "a remote centralized government … possessed of great industrial and technological might, but unable, due to the sheer distances and travel times involved, to exert total control everywhere within its star-spanning realm."

Fans of the game were quick to pick up on this reference it wasn't long before GDW presented a pre-generated sector of space for use by the referee who didn't wish to roll up his own, along with some details on the Imperium (now dubbed "the Third Imperium") of which it was a part. The Spinward Marches and the Third Imperium both proved very popular with Traveller fans and soon became inextricably linked with the game, even though Traveller was still perfectly usable as the basis for a SF setting of one's own creation. By the time I started playing the game in 1982, by which point GDW had already published a second pre-generated sector, I encountered almost no one who played Traveller in any setting other than that of the Third Imperium.

Though The Spinward Marches and other GDW products began to fill in the details of the Third Imperium and its interstellar neighbors, these details were initially quite sketchy and open to interpretation. During the period between 1979 and 1982 (or thereabouts), several third parties, like Judges Guild, were licensed by GDW to produce their own pre-generated sectors to fill in the larger map of "Charted Space" that the Third Imperium occupied. Many of these non-GDW sectors were quite idiosyncratic in their contents and would later be partially or wholly excised from the Traveller canon, as it solidified into something more definite.

One of the better examples of these third-party sectors was Beyond, written by Donald P. Rapp and published by Paranoia Press in 1981. Located "beyond the Great Rift, beyond the Imperium and beyond the law," the titular sector is a wild place, consisting of nearly 500 worlds inhabited by a mix of humans, Droyne, Aslan, and several unique alien species. It's also home to a number of interstellar governments that are independent of the Imperium and the other great empires of Charted Space. Consequently, Beyond is presented as a region of space that's perfect for adventurers who wish to avoid any "imperial entanglements," to borrow a phrase.

Beyond mimics the format and presentation of The Spinward Marches, being a 32-page digest-sized booklet, with each of Beyond's sixteen subsectors having a single page for its listing of world data. There are also six pages at the back of the book dedicated to "library data," Traveller's term for background information presented in a series of brief, faux encyclopedia-style entries. It's in the latter that we learn about the Church of Resurgent Anthropomorphic Philosophy, Starbase Arcturus II, the Zydarian Codominium, and more. The library data also describes Beyond's unique alien races, such as the arachnid-like Sred*Ni and the flying Mal'Gnar.

As you can see, Beyond is filled with a plethora of hyphens, apostrophes, and asterisks, not to mention lengthy names with convenient – or "humorous," as in the case of the aforementioned Church – acronyms. Taken together, this gives the sector a very different feel than the more sober, even stolid, approach GDW took with its own pre-generated sectors. That's not necessarily a bad thing and it certainly gives Beyond a distinct flavor that sets it apart – a flavor that might not be to everyone's taste. I know that, when I was a younger man, I didn't think much of Beyond (or its companion from Paranoia Press, Vanguard Reaches), precisely because it was less "serious" than GDW's own efforts. Nowadays, I'm a great deal more tolerant of Beyond's oddities, perhaps because I better appreciate the need for different styles and approaches within established settings, such as Traveller's Charted Space.

Mostly, though, Beyond is a relic from an earlier time in the history of Traveller, before the game had evolved to the point where one needed to know a large amount of background information scattered over multiple books to be able to understand its setting. Fond though I remain of the Third Imperium and its richly detailed history, I recognize that it can be very off-putting to newcomers, who simply want to engage in "science fiction adventures in the far future," to quote Traveller's longstanding tagline. Supplements like Beyond facilitate that pretty well and we could probably use more like it.

September 20, 2022

White Dwarf: Issue #50

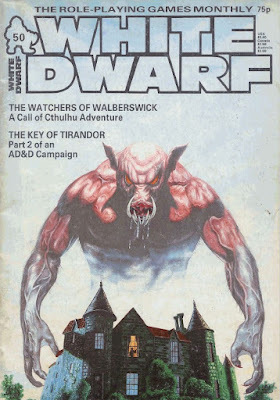

Issue #50 of White Dwarf (February 1984) is an important milestone for the magazine, marking nearly seven years of continuous publication since its premier in June 1977. The cover, by Terry Oakes, is an odd choice for such a momentous issue. It's a re-use of an earlier painting used as the cover for the 1980 UK paperback edition of William Hope Hodgson's House on the Borderland. Why it was chosen in this instance, I have no idea, though the swine-things from the story are sometimes cited as possible precursors to the pig-faced orcs of which old school D&D fans such as myself as so fond.

Issue #50 of White Dwarf (February 1984) is an important milestone for the magazine, marking nearly seven years of continuous publication since its premier in June 1977. The cover, by Terry Oakes, is an odd choice for such a momentous issue. It's a re-use of an earlier painting used as the cover for the 1980 UK paperback edition of William Hope Hodgson's House on the Borderland. Why it was chosen in this instance, I have no idea, though the swine-things from the story are sometimes cited as possible precursors to the pig-faced orcs of which old school D&D fans such as myself as so fond.Garth Nix's "A Few Small Formalities …" kicks off the issue proper, with a humorous discussion of the use and abuse of bureaucratic red tape in Traveller. Accompanying the article are four sample forms the referee can inflict on players when their characters must interact with meddlesome local planetary rules and regulations. I've always enjoyed articles of this kind, but then I'm also fond of scenarios like the infamous "Exit Visa" from The Traveller Book, too, so perhaps I'm a poor judge of such things.

"Open Box" reviews a large number of interesting RPG products in this issue, starting with Steve Jackson's Sorcery!, which receives a rating of 7 out of 10. There are also reviews of several Middle-earth Role Playing supplements: A Campaign and Adventure Guidebook (6 out of 10), Angmar – Land of the Witch King (7 out of 10), The Court of Ardor (7 out of 10), Umbar – Haven of the Corsairs (7 out of 10), Northern Mirkwood – The Wood Elves' Realm (8 out of 10), and Southern Mirkwood – Haunt of the Necromancer (8 out of 10). Reading these reviews fills me with a great deal of nostalgia for the days of Iron Crown Enterprise's series of Middle-earth sourcebooks, only a few of which I ever actually owned. The issue's last review is Tarsus for Traveller, which receives a much deserved 9 out of 10 rating.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" is fascinating to me in that it regularly reviews books I never heard of, let alone read. This installment of the column is no different. The only book Langford discusses with which I am directly familiar is Helliconia Summer by Brian Aldiss, of which he thinks very highly (I was less impressed; my favorite of his novels has always been Non-Stop). Meanwhile, "White Dwarf Personalities" by Phil Masters and Steve Gilham is a fun little piece in which people and characters associated with the magazine, such as Ian Livingstone, Thrud the Barbarian, and the eponymous White Dwarf are given RPG stats for either AD&D or RuneQuest (sometimes both).

Speaking of Thrud, we get new episodes of his comic, along with Gobbledigook, and The Travellers. "Divinations and the Divine" by Jim Bambra is a workmanlike article on clerics in AD&D, focusing on the role of the class both in play and within the fictional "society" of a campaign. It's fine for what it is and clearly geared toward newcomers, but it's vastly better than many of the beginner's articles that White Dwarf ran in its early issues. "The Watchers of Walberswick" by Jon Sutherland is a short introductory scenario for use with Call of Cthulhu, dealing with the Deep Ones along the Suffolk coast of England. It's a solid, straightforward piece of work that could easily serve as the start of a new UK-based campaign.

"RuneQuest Hardware" by Dean Aston is a collection of new equipment for use with RQ. The items in question are an odd group, running the gamut from the mundane (nunchaku – hey, it was the '80s) to the exotic (magic talismans) and downright weird (hollow panel detector). Part 2 of "The Key to Tirandor" by Mike Polling brings a part of AD&D characters inside the titular city. The city is a very strange place, even by the standards of a fantasy roleplaying game, but there's an explanation for its many oddities – the city is an illusion, a projection of an insane dreamer's imagination – and discovering this truth is what the scenario is about. I have mixed feelings about this myself, though I recognize that there's a lot to be said in favor of breaking the usual mold of D&D adventures.

"Have Computer, Will Travel" by Marcus L. Rowland presents a couple of BASIC computer programs to aid in the creation of vehicles in Striker. I can't rightly comment on their utility, but, like the inclusion of nunchaku earlier, the inclusion of a computer program in a RPG magazine is a hallmark of the 1980s. "Going Up" by Lewis Pulsipher presents a new system for advancement in D&D that dispenses with experience points altogether, opting instead for tracking the number of sessions in which a character participates as a gauge of advancement. It's an interesting idea, especially for it time, though I am unsure of how it would work in practice.

"One Ring to Rule Them All" by Charles Vasey is a lengthy examination of Iron Crown's Fellowship of the Ring fantasy boardgame. Part review, part strategy guide, it's the kind of article that would probably appeal most to those who've played the game in question. Since I have not, there's not much more I can say about it. "An Assassins Special" by M.J. Stock, on the other hand, describes four new items for use by assassins in AD&D, ranging from the garotte to a dagger of slaying. It's another workmanlike article whose utility depends almost entirely on whether or not a referee sees the need for more specialized equipment in his campaign. Finally, there's "Baelpen Bulletins," which collects news items from the far-flung corners of the hobby scene, including several tidbits that never came to pass (such as FASA's Battlestar Galactica RPG and Close Simulation's Road Warrior RPG).

Milestone issues are always a challenge, I suspect, because there's a natural expectation that their content will necessarily be "special" in some way. That mostly wasn't the case here and that's no knock against the issue. For the most part, issue #50 is simply another decent, if unexceptional, issue of White Dwarf. The main thing that it does well is present a wide variety of content covering many different games from many different companies, which is no small thing. Here's to the next fifty issues!

September 19, 2022

Fun and Challenges

One of the things at which the OSR excels is categorization and the creation of jargon to encapsulate these new categories. Though perhaps inevitable in any thoroughgoing examination of ideas, these practices can be somewhat off-putting to newcomers, not to mention conducive to tedious obscurantism. At the same time, categories and verbal shorthand are genuinely useful, despite the confusion they can engender to those not well versed in their intricacies.

As its title suggests, dungeons are a foundational element of the play of Dungeons & Dragons. It should, therefore, come as no surprise that, since its inception, the OSR had devoted a lot of virtual ink examining and re-examining dungeons from nearly every possible angle. Consequently, there's also been a concomitant amount of jargon invented to describe dungeons and aspects of them, such as megadungeon or the term I want to talk about now, funhouse dungeon.

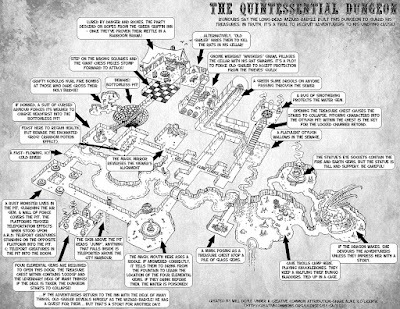

Take a look at this map:

The image above is small, so please click to enlarge it and examine its details. The map originally appeared here and is entitled "The Quintessential Dungeon." It's a really nice piece of work in my opinion, both in terms of the brief way it presents its information but also – and perhaps more importantly for my present purposes – the way it manages to include so many well-worn components of old school dungeons. There's a bottomless pit, an alignment-reversing mirror, collapsing stairs, and a subterranean river, not to mention such de rigueur monsters like a rust monster, a mimic, and green slime.

The image above is small, so please click to enlarge it and examine its details. The map originally appeared here and is entitled "The Quintessential Dungeon." It's a really nice piece of work in my opinion, both in terms of the brief way it presents its information but also – and perhaps more importantly for my present purposes – the way it manages to include so many well-worn components of old school dungeons. There's a bottomless pit, an alignment-reversing mirror, collapsing stairs, and a subterranean river, not to mention such de rigueur monsters like a rust monster, a mimic, and green slime. I find "The Quintessential Dungeon" utterly delightful in the way it sincerely and unironically celebrates all the things I so strongly associate with my early experiences of playing Dungeons & Dragons. (It also reminds me a bit of Zarakan's Dungeon from Down in the Dungeon, which may explain its appeal to me.) I think it's a good example of the kind of thing that some might call a funhouse dungeon, in that it contains a weird mélange of tricks, traps, and monsters seemingly lacking in a unifying principle (beyond the suggestion that the place is a wizard's testing ground to recruit adventurers.

Over the years, I've used the term funhouse dungeon without any qualms. Indeed, I've even use the term in reference to some of my favorite published D&D adventures, like White Plume Mountain and Castle Amber. Though I meant no disrespect to the designs of these modules by my use of the term, I've lately started to think "funhouse dungeon" might be too glib a term for what we're talking about in most cases. The essential feature of dungeons of this sort is not that they're chaotic jumbles devoid of any rhyme or reason but that they include lots of deadly challenges intended to test the mettle and ingenuity of the characters who dare to enter them.

My point – assuming I have one – is that, rather than being silly, what we typically call funhouse dungeons are actually quite serious, in the sense that surviving them requires more than a hack 'n slash approach to its contents. Likewise, the varied nature of those contents should be viewed not as an anarchic mess but as yet another aspect of its challenging nature. Because one room might contain a group of trolls who've captured a halfling and the next a teleportation trap, the players have to keep on their toes in a way they might not in a dungeon that follows more naturalistic principles.

Perhaps I make too much out of what is ultimately little more than a terminological issue. What I most wanted to say in this post is that I think, as I have grown older, I've acquired a much greater respect for dungeons whose primary purpose is to present a gauntlet of clever tricks, cruel traps, and gimmicky monsters for the characters to overcome in pursuit of gold and experience points. I used to think less of dungeons of this sort. Nowadays, I recognize that funhouse dungeons – or whatever better term might replace it – can be every bit as satisfying, not to mention terrifying, as more plausibly built subterranean labyrinths.

Terrifyingly Beautiful

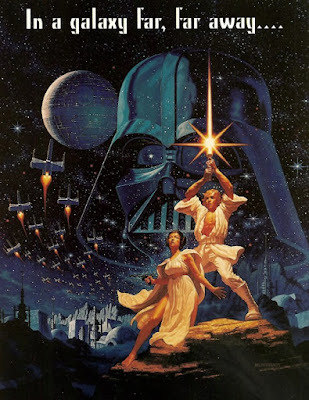

If you were into fantasy during the 1970s, you were almost certainly familiar with the artwork of Greg and Tim Hildebrandt, generally known as the Brothers Hildebrandt. Today, they're probably most remembered for their various Lord of the Rings calendars (the first of which appeared in 1976) and the covers to the Shannara novels of Terry Brooks, but I suspect the first of their paintings I ever saw was this one:

To say the Brothers Hildebrandt were a big deal is thus something of an understatement. That's why I'm not at all surprised that, in 1982 and 1983, TSR released two Dungeons & Dragons calendars featuring paintings by Tim Hildebrandt (I wonder why Greg was not also involved in this project). Here's an ad for the 1984 calendar from Dragon:

To say the Brothers Hildebrandt were a big deal is thus something of an understatement. That's why I'm not at all surprised that, in 1982 and 1983, TSR released two Dungeons & Dragons calendars featuring paintings by Tim Hildebrandt (I wonder why Greg was not also involved in this project). Here's an ad for the 1984 calendar from Dragon:

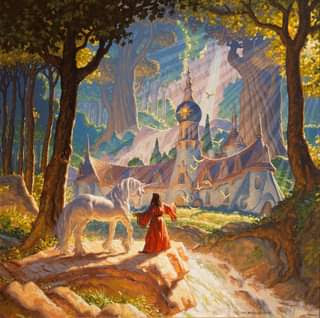

Did anyone reading this own one of these calendars? Searches online reveal that the calendar's paintings, while indeed beautiful, are fairly generic in their subject matter. I don't see anything distinctly D&D-ish about this, for example:

Did anyone reading this own one of these calendars? Searches online reveal that the calendar's paintings, while indeed beautiful, are fairly generic in their subject matter. I don't see anything distinctly D&D-ish about this, for example:

Mind you, it's an open question as to what marks any artwork as "Dungeons & Dragons artwork" beyond the fact that it appeared in a D&D product, so perhaps I'm being unfair. More to the point, I imagine TSR didn't worry much about such questions. For them, the union of the D&D name and the artwork of one of the world's premier fantasy artists was likely sufficient justification for the existence of Realms of Wonder.

Mind you, it's an open question as to what marks any artwork as "Dungeons & Dragons artwork" beyond the fact that it appeared in a D&D product, so perhaps I'm being unfair. More to the point, I imagine TSR didn't worry much about such questions. For them, the union of the D&D name and the artwork of one of the world's premier fantasy artists was likely sufficient justification for the existence of Realms of Wonder.

September 18, 2022

Pulp Science Fiction Library: Hunters of the Sky Cave

Recently, one of the players in my House of Worms campaign offered to referee Traveller for myself and several others. Since Traveller likely remains my favorite roleplaying game of all time, I jumped at the chance to participate. This will be the first time I've ever used the Mongoose Traveller rules, so I'm looking forward to seeing how they differ from the classic GDW rules I've nearly always used in the past (the exception being GURPS Traveller, which I last played more than twenty years ago – my goodness, how time flies!).

Recently, one of the players in my House of Worms campaign offered to referee Traveller for myself and several others. Since Traveller likely remains my favorite roleplaying game of all time, I jumped at the chance to participate. This will be the first time I've ever used the Mongoose Traveller rules, so I'm looking forward to seeing how they differ from the classic GDW rules I've nearly always used in the past (the exception being GURPS Traveller, which I last played more than twenty years ago – my goodness, how time flies!).

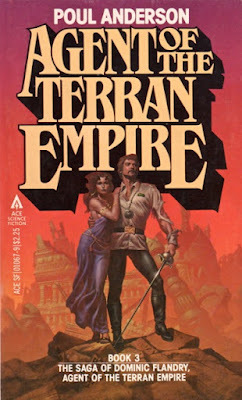

Anytime I start thinking about Traveller and its Third Imperium setting, my mind inevitably drifts toward the science fiction authors and stories that inspired them. Standing alongside the Dumarest of Terra series by E.C. Tubb is the Flandry saga of Poul Anderson, the earliest stories of which first appeared in the 1950s, but were collected and anthologized throughout the '60s, '70s, and '80s. That's how I first encountered them and I retain an inordinate fondness for the collections published by Ace with covers by the great Michael Whelan, like the one that accompanies this post.

The third of the Ace volumes, entitled Agent of the Terran Empire, included the story "Hunters of the Sky Cave," which was itself an expansion of an earlier short story originally published in 1959 under the title "A Handful of Stars" (and occasionally reprinted under yet another title, "We Claim These Stars!:). In terms of its writing, it's one of the earliest of Anderson's Flandry tales, though it takes place during the middle of the character's career as an agent of the faltering Terran Empire. Captain Sir Dominic Flandry is commonly described as a "science fiction James Bond" in that he's a debonair spy with an eye for the finer things in life, though his fans are quick to point out that he predates the first appearance of Bond by two years.

At the start of "Hunters of the Sky Cave," Flandry is attending a feast and a ball thrown by Ruethen of the Long Hand, the Merseian ambassador to the Terran Empire. The Merseians are an alien species whose own expanding empire is a rival to that of the Terrans. The ball is thus an occasion for Flandry to gather intelligence on the Merseians – and attempt to seduce Diana Vinogradoff, Right Lady Guardian of the Mare Crisium, as part of "a thousand-credit bet with his friend," Ivar del Bruno, who insisted that the noblewoman "would never bestow her favors upon anyone under the rank of earl." This sort of behavior is typical of Flandry and is at least in part a consequence of his vocation, as he remarks to himself:

Terra has been rich for too long; we've grown old and content, no more high hazards for us. Whereas the Merseian Empire is fresh, vigorous, disciplined, dedicated, et tedious cetera. Personally, I enjoy decadence; but somebody has to hold off the Long Night for my own lifetime, and it looks as if I'm elected.

The eyebrows of Traveller aficionados should immediately arch at the reference to the Long Night, the collapse of interstellar civilization against which Flandry struggles vainly across his long career in service to the Empire. Marc Miller borrowed the name for the future history of the game's official setting to describe the period between the fall of the Second Imperium and the rise of the Third.

In any case, Flandry never gets the chance to enjoy the company of Lady Diana. Instead, he's summoned to the office of Vice Admiral Fenross, his superior in Naval Intelligence, who tasks him with a mission to the planet Vixen. "A space fleet appeared several weeks ago and demanded that it yield to occupation," Fenross explained. The ships of the fleet "were of exotic type, and the race crewing them can't be identified." Fenross worries the unknown aliens occupying Vixen were secretly in alliance with the Merseians – which is why he intends to send Flandry to Vixen to find out what is actually going on and deal with it in any way he can.

To prepare for his mission, Fenross puts Flandry in touch with a Vixenite named Catherine Kittredge, who escaped the planet and headed for Terra with information about the invaders.

"They call themselves the Ardazirho, an' we gathered the ho was collective endin'. So we figure their planet is named Ardazir. Though I can't come near to pronouncin' it right."

Flandry took a stereopic from the pocket of his iridescent shirt. It had been snapped from hiding, during the ground battle. Against a background of ruined human homes crouched a single enemy soldier. Warrior? Acolyte? Unit? Armed, at least, and a killer of men.

Preconceptions always got in the way. Flandry's first thought had been Wolf! Now he realized that of course the Ardazirho was not lupine, didn't even look notably wolfish. Yet the impression lingered. He was not surprised when Catherin Kittredge said the aliens had gone into battle howling.

They were described as man-size bipeds, but digitigrade, which gave their feet almost the appearance of a dog's walking on its hind legs. The shoulders and arms were very humanoid, except that the thumbs were on the opposite side of the hands from mankind's. The head, arrogantly held on a powerful neck, was long and narrow for an intelligent animal, with a low forehead, most of the brain space behind the pointed ears. A black-nosed muzzle, not as sharp as a wolf's and yet somehow like it, jutted out of the face. Its lips were pulled back in a snarl, showing bluntly pointed fangs which suggested a flesh-eater turned omnivore. The eyes were oval, close set, and gray as sleet. Short thick fur covered the entire body, turning to a ruff at the throat; it was rusty red.

"Is this a uniform?" asked Flandry.

The girl leaned in close to see. The pictured Ardazirho wore a sort of kilt, in checkerboard squares of various hues. Flandry winced at the combinations: rose next to scarlet, a glaring crimson offensively between two delicate yellows. "Barbarians indeed," he muttered.

Once again, the connection to Traveller should be obvious, as the game's official setting includes a species of wolflike aliens known as the Vargr and whose fashion sense tends toward the garish by human standards.

Of course, "Hunters of the Sky Cave" is much more interesting than as the source of inspiration for Traveller. Once Flandry gets to Vixen, he quickly discovers that there's more going on than anyone suspected and that, despite his own initial doubts, the invasion of the planet likely plays a role in the Merseians' ongoing attempts to undermine the stability of the Terran Empire. What follows then is a fast-paced and clever bit of space opera, filled with equal parts intrigue, derring-do, and, above all, interesting characters. Anderson excels at the latter, bringing surprising depth and complexity even to Flandry's antagonists, who are more than mere "barbarians." It's a great science fiction short story and well worth your time.

September 16, 2022

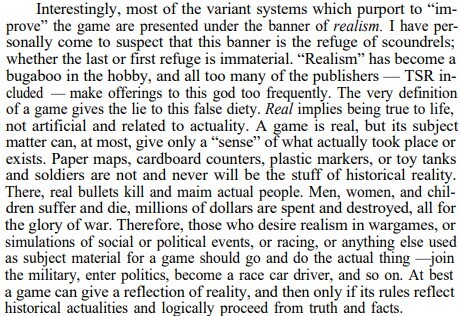

A Bugaboo in the Hobby

It's a shame that Gygax was so quick to employ strawmen in his jeremiads, because they often undermined the legitimate point he was trying to make. No game, no matter how finely detailed or complex in its rules, will ever adequately simulate reality, which is why the single-minded pursuit of realism is, as he calls it, a "false deity." This is a perfectly reasonable position for a game designer to take (though I may be biased in saying so, as it's close to my own position on the matter). Gygax had no need for overblown rhetorical flourishes, such as the suggestion that those who want realism in their games "join the military, enter politics, become a race car driver" to experience it – and I say this as someone who is broadly sympathetic to his perspective.

It's a shame that Gygax was so quick to employ strawmen in his jeremiads, because they often undermined the legitimate point he was trying to make. No game, no matter how finely detailed or complex in its rules, will ever adequately simulate reality, which is why the single-minded pursuit of realism is, as he calls it, a "false deity." This is a perfectly reasonable position for a game designer to take (though I may be biased in saying so, as it's close to my own position on the matter). Gygax had no need for overblown rhetorical flourishes, such as the suggestion that those who want realism in their games "join the military, enter politics, become a race car driver" to experience it – and I say this as someone who is broadly sympathetic to his perspective.

Here, however, I must part company with Gygax. Very few things are "pure fantasy," which is to say, utterly divorced from our real world. Even places like Edwin A. Abbott's Flatland obey recognizable and indeed logical rules that are intelligible even to three-dimensional beings. Most fantasy settings, even the most whimsical, contain innumerable elements that we must presume operate according to the laws of mundane reality, unless we are told otherwise. Does anyone really doubt, for example, that the inhabitants of a fantasy world must eat or sleep, just as we do? The mere presence of one or more fantastical elements in a setting does not suggest that the operation of everything in that setting follows its own unique – and unintelligible – rules. Again, this is desperate rhetoric.

Here, however, I must part company with Gygax. Very few things are "pure fantasy," which is to say, utterly divorced from our real world. Even places like Edwin A. Abbott's Flatland obey recognizable and indeed logical rules that are intelligible even to three-dimensional beings. Most fantasy settings, even the most whimsical, contain innumerable elements that we must presume operate according to the laws of mundane reality, unless we are told otherwise. Does anyone really doubt, for example, that the inhabitants of a fantasy world must eat or sleep, just as we do? The mere presence of one or more fantastical elements in a setting does not suggest that the operation of everything in that setting follows its own unique – and unintelligible – rules. Again, this is desperate rhetoric.

Gygax does a better job of explaining his position in this paragraph, though I still think he is (deliberately?) missing the point of those who want realism in their games. I fully agree with him that, once the logic of a setting is fully explicated and thereby understood by the players of a game, it can become a substitute for the logic of the real world within the game. I suspect most people reading this post have, at some point, been involved in a game session in which some matter was resolved by reference to the underlying "rules" of a setting's reality. That's a regular occurrence in my House of Worms campaign and indeed one of its great joys.

Gygax does a better job of explaining his position in this paragraph, though I still think he is (deliberately?) missing the point of those who want realism in their games. I fully agree with him that, once the logic of a setting is fully explicated and thereby understood by the players of a game, it can become a substitute for the logic of the real world within the game. I suspect most people reading this post have, at some point, been involved in a game session in which some matter was resolved by reference to the underlying "rules" of a setting's reality. That's a regular occurrence in my House of Worms campaign and indeed one of its great joys. At the same time, I'm not completely certain that this is all that relevant to the concerns of those who want realism in, say, the combat system of their favorite RPG. What the advocates of realism generally want, in my own experience anyway, is a mechanical system that better reflects the way the things being modeled operates in the real world. Thus, a realistic combat system might take into account things like bleeding, broken bones, shock, and so on. D&D's combat system emphasizes not realism but ease and efficiency of play, which is a perfectly valid emphasis. That some might want a combat (or any other) system that more closely models reality is no cause for derision, even if the desire is at odds with Gygax's own preferences and the approach he adopted in his own design.

I could quibble with some of what Gygax says here, but, by and large, I think he acquits himself well here. That said, he still doesn't quite seem to understand why some people, even if they're only a minority, desire greater realism in their game system than D&D has on offer.

I could quibble with some of what Gygax says here, but, by and large, I think he acquits himself well here. That said, he still doesn't quite seem to understand why some people, even if they're only a minority, desire greater realism in their game system than D&D has on offer.

I agree with Gygax that, after a certain point, if you make enough changes to Dungeons & Dragons, you're not really playing Dungeons & Dragons anymore and you might as well be making your own game. We probably wouldn't have as many roleplaying games as we do if it others hadn't come to a similar conclusion on their own. Likewise, I readily accept the notion that D&D – or at least AD&D – was, in some sense, designed with particular goals in mind and that its rules, however seemingly haphazard they are in places, are intended to serve genuine purposes. Modifying or removing them without due consideration for their intended purposes can be detrimental to the working of the whole. The problem is that Gygax seemed to think that only he was in a position to determine which "additions to and augmentations of" D&D were fine and which were not.

I agree with Gygax that, after a certain point, if you make enough changes to Dungeons & Dragons, you're not really playing Dungeons & Dragons anymore and you might as well be making your own game. We probably wouldn't have as many roleplaying games as we do if it others hadn't come to a similar conclusion on their own. Likewise, I readily accept the notion that D&D – or at least AD&D – was, in some sense, designed with particular goals in mind and that its rules, however seemingly haphazard they are in places, are intended to serve genuine purposes. Modifying or removing them without due consideration for their intended purposes can be detrimental to the working of the whole. The problem is that Gygax seemed to think that only he was in a position to determine which "additions to and augmentations of" D&D were fine and which were not.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers