James Maliszewski's Blog, page 93

November 17, 2022

Retrospective: Swords & Glory

As early roleplaying game go, Empire of the Petal Throne is fairly well known, if only for the fact that it was the second RPG published by TSR, just about a year and a half after the release of OD&D. EPT is legendary, too, for its price tag – $25 – which was a considerable sum in 1975 (D&D, by contrast, retailed for $10). Of course, what makes the game truly stand out is its setting, the alien planet of Tékumel, one of the greatest works of the imagination in the history of the hobby.

As early roleplaying game go, Empire of the Petal Throne is fairly well known, if only for the fact that it was the second RPG published by TSR, just about a year and a half after the release of OD&D. EPT is legendary, too, for its price tag – $25 – which was a considerable sum in 1975 (D&D, by contrast, retailed for $10). Of course, what makes the game truly stand out is its setting, the alien planet of Tékumel, one of the greatest works of the imagination in the history of the hobby.Tékumel stands out in part because it differs in many ways, both small and large, from the assumptions of D&D's idiosyncratic brand of fantasy. Instead, it draws more "from Egypt, the Aztecs and Mayans, the Hellenic Age, Mughal India, and mediaeval Europe," giving it a strong and unique flavor of its own. For all of its virtues, Empire of the Petal Throne didn't wholly do justice to it and so it was perhaps inevitable that there would one day be a "second edition" of sorts, one that might more fully exemplify Tékumel and its rich history and cultural details.That putative second edition arrived with two boxed sets from Gamescience released under the title of Swords & Glory. The first of these, Tékumel Source Book: The World of the Petal Throne, appeared in 1983 and consisted of a 136-page softcover book and a large, double-sided map in full color. The second, Tékumel Player's Handbook: Adventures in Tékumel, came with a 240-page softcover book, some character sheets, and two polyhedral dice. Together, they constitute an attempt to present a more fully realized vision of Tékumel as a setting for fantasy roleplaying. They only partially succeed in the attempt, for numerous reasons, as I shall explain.

The Tékumel Source Book is a truly wondrous volume. In its cramped columns, whose tiny text is decorated with innumerable hand-drawn accent marks, the reader is treated to an exhaustive examination of nearly every aspect of the setting. The Source Book begins with a treatment of the physical aspects of Tékumel – its solar system, geography, weather – and then moves on to its lengthy history, inhabitants (both human and nonhuman), and the cultures, both large and small, that can be found on one of its continents. Each of those cultures is further described in detail. Everything from family and social structure, religion, entertainments, militaries, housing, and more is laid out in a dry, quasi-academic style that would be severely off-putting if it weren't so compelling. Compared to nearly anything else available on the market at the time, the Tékumel Source Book is masterwork of RPG setting design.

The Tékumel Player's Handbook is far less impressive. Much of it is given over to needlessly complex and detailed treatments of various mid-1980s roleplaying obsessions, particularly in the area of combat. Rather than better grounding the rules in the setting of Tékumel – something that would have been welcome – the reader is instead subjected to discourses on encumbrance, skill development, and height-build factors, among other things. I don't mean to be overly critical of this; plenty of RPGs at the time were similarly punctilious about this kind of thing. However, little of this does much to support the setting of Tékumel, which is the main selling point of Swords & Glory. At least the spells presented in the Player's Handbook do this very well or else there'd be little else to recommend the book.

There should have been a third boxed set that would have presented material intended for the referee, such as monsters, magic items, and other information necessary to use the first two sets as part of an extended campaign on Tékumel. However, that set never appeared and, as a result, Swords & Glory was never really playable in the way that Empire of the Petal Throne was, despite its inadequacies as a vehicle for presenting Tékumel to roleplayers. That's certainly unfortunate, but I reckon that Swords & Glory was already something of a misstep even before it became clear that it would never be a complete game system.

That's the real tragedy of a game like Swords & Glory. What was originally intended as a better presentation of a rich and complex setting like Tékumel became bogged down in minutiae and unnecessary accretions to the point where it likely turned many people off ever giving the setting a fair hearing. While I adore the Tékumel Source Book and its lengthy digressions on the governmental structures of remote tribal peoples and the entertainments enjoyed by the flying Hláka species, they're likely discouragements to newcomers who simply want a straightforward presentation of Tékumel, why it's a terrific fantasy RPG setting, and, above all, what to do with it all. Nowhere does Swords & Glory even approach working toward providing any of this, leading to a game that was probably less read or played than the original Empire of the Petal Throne.

As a diehard fan of Tékumel, I can't help but shake my head at the missed opportunity that Swords & Glory represents. Tékumel is too good a setting to languish in the shadowy corners of roleplaying history. Yet, it's never really had a solid, approachable game version that would be appealing to complete neophytes. Instead, it's been saddled with a succession of ill-conceived and poorly presented games that have only reinforced the false notion that Tékumel is inaccessible to all but a chosen few. What a shame ...

November 15, 2022

White Dwarf: Issue #58

Issue #58 of White Dwarf (October 1984) has a terrific cover by Chris Achilleos, an artist whose work I've long appreciated. Ian Livingstone's editorial bemoans the fact that Chaosium has signed a deal with Avalon Hill to publish the next edition of RuneQuest, which will retail at a much higher price in the UK, owing to import costs. Those import costs will be necessary since Avalon Hill has terminated Games Workshop's license to produce a British edition of the game. Livingstone goes on to speculate that this move will undermine RQ's growth in the UK. Whether he was correct in his prediction, I can't say. All I know for sure is that, for several years in the 1980s, RuneQuest was more popular than Dungeons & Dragons in Britain, which baffled my younger self, who could scarcely conceive the possibility that D&D would ever play second fiddle to another fantasy RPG (or indeed any other game).

Issue #58 of White Dwarf (October 1984) has a terrific cover by Chris Achilleos, an artist whose work I've long appreciated. Ian Livingstone's editorial bemoans the fact that Chaosium has signed a deal with Avalon Hill to publish the next edition of RuneQuest, which will retail at a much higher price in the UK, owing to import costs. Those import costs will be necessary since Avalon Hill has terminated Games Workshop's license to produce a British edition of the game. Livingstone goes on to speculate that this move will undermine RQ's growth in the UK. Whether he was correct in his prediction, I can't say. All I know for sure is that, for several years in the 1980s, RuneQuest was more popular than Dungeons & Dragons in Britain, which baffled my younger self, who could scarcely conceive the possibility that D&D would ever play second fiddle to another fantasy RPG (or indeed any other game).The issue proper begins with Stephen Dudley's "It's a Trap!," which looks at designing traps in AD&D and other fantasy games. Though short, it's a thoughtful look at the subject and includes an example to illustrate Dudley's main points. In short, he suggests that while traps need not be "realistic," they should nevertheless function according to an intelligible logic. Likewise, the referee should include a means of disarming them or, lacking that, a means to circumnavigate them, even if doing so presents different challenges. "Open Box" begins with a mediocre (5 out of 10) review of FGU's Lands of Adventure, a game I've long wanted to see but never have. If the review is any indication, I'm not missing much. More favorably reviewed is Middle-earth Role Playing. The game scores 9 out of 10 in its book form and 7 out of 10 in its boxed form, based on the fact that the boxed set is more expensive and doesn't offer enough any significant additional value. Bree and the Barrow Downs, on the other hand, only garners 6 out of 10, because it's more a sourcebook than an adventure and thus of much more limited utility. Q Manual for the James Bond 007 RPG receives a much deserved 9 out of 10. It's one of the few RPG equipment books I've ever felt deserving of real praise. Finally, there's Star Trek the Role Playing Game , another favorite of mine. The reviewer gives it 9 out of 10 and I'd be hard pressed to disagree.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" keeps chugging along, reviewing plenty of novels I've never heard of, let alone read, along with a few I have. Most notable this issue is his praise for Robert Holdstock's Mythago Wood and his dislike of Jack Chalker's Twilight at the Well of Souls. The third part of "Night's Dark Agents" by Chris Elliott and Richard Edwards is surprisingly good. Whereas the previous two installments were filled with the usual mid-80s gaming material about ninjas, this one focuses on the nitty gritty details of how ninjas operated in the field. The material on their preparations and the tactics employed is both interesting and useful, as is the material intended for referees in running ninja-based games. Not being as enamored of ninjas as many gamers, I was impressed that this article held my attention as much as it did.

"Beyond the Final Frontier" by Graeme Davis is not, as its title might suggest, an article about roleplaying in the Star Trek universe. Rather, it's an examination of the beliefs of various real world historical cultures about death and the afterlife in the context of continuing to play a character in a fantasy RPG after he has died. The article is sadly short, but Davis offers some useful ideas for how to handle this in a campaign. "Grow Your Own Planets" presents a computer program, based on then-current astrophysics, that generates star systems and the details of the planets therein. Given the date of its creation, the program is necessarily limited in its output, but I can imagine it would have been very appealing to referees of science fiction RPGs.

"Strikeback" by Marcus L. Rowland is an adventure for use with Champions or Golden Heroes. The scenario is a fun one involving time travel, the Bavarian Illuminati, Baron Frankenstein, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes, and more. It's a kind of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen romp before the fact and, speaking as someone who made use of the adventure at the time, I highly recommend it. "Chun the Unavoidable" by Oliver Johnson, meanwhile, is an adaptation of certain elements of Jack Vance's The Dying Earth for use as a low-level AD&D scenario. I really liked this in my youth, largely for its write-ups of archveults, deodands, and pelgranes, in additional to the eponymous Chun the Unavoidable.

"For a Few Credits More" by Thomas Price looks at the subject of money in Traveller. This is a solid treatment and I appreciate the way Price considers the ways that technology, whether high or low, might impact currency. Naturally, as an article written in the pre-Internet age, some details look dated – or perhaps "quaint" is a better word – but then Traveller has always been slightly retro, so this isn't really a knock against it. "Thinking in Colour" by Joe Dever and Gary Chalk presents helpful hints on the matter of shading, highlighting, and mixing paints for miniatures. Once again, I find myself wishing I'd devoted more time and effort to learning how to paint in my youth.

"Cameos" by Peter Whitelaw presents two short scenarios for use with RuneQuest. Both are set in Pavis and are quite short, so the referee will need to flesh them out considerably before making use of them. That said, they're both quite flavorful and do a good job of showing off what makes Glorantha such a compelling fantasy setting. "Bigby's Helping Hand" includes yet more ideas for using AD&D spells in unusual ways, along with ideas for using beggars as NPCs. Also included in this month's issue are further episodes of "Gobbledigook," "Thrud the Barbarian," and "The Travellers," the last of which receives a two-page spread.

This is a very good issue of White Dwarf and one whose content I enjoyed and made use of once upon a time. Re-reading it, I was reminded on several occasions of just how vibrant the magazine was at its height. There's a good variety of material and it's quite well presented. Though I was naturally more well inclined toward Dragon, there's little question in mind that, when White Dwarf was firing on all cylinders, it was the superior magazine. Issue #58 is a good example of that superiority.

November 13, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Demon of the Flower

In previous posts about the stories of Clark Ashton Smith, I've sometimes mentioned contemporary criticisms of them. The claim that Smith's fiction often consists of prose poetry is a common one, followed closely by the suggestion that his tales often lack action. That was certainly August Derleth's assessment of "The Demon of the Flower" when he read a draft of it before CAS sent it to Strange Tales. He felt certain that Harry Bates, editor of the magazine, would reject it for this very reason. As it turned out, Derleth was partly mistaken. Bates initially accepted the story for publication. only to be overruled by his publisher, William Clayton. The story met the same fate when Smith submitted it to Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales.

In previous posts about the stories of Clark Ashton Smith, I've sometimes mentioned contemporary criticisms of them. The claim that Smith's fiction often consists of prose poetry is a common one, followed closely by the suggestion that his tales often lack action. That was certainly August Derleth's assessment of "The Demon of the Flower" when he read a draft of it before CAS sent it to Strange Tales. He felt certain that Harry Bates, editor of the magazine, would reject it for this very reason. As it turned out, Derleth was partly mistaken. Bates initially accepted the story for publication. only to be overruled by his publisher, William Clayton. The story met the same fate when Smith submitted it to Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales. Eventually, "The Demon of the Flower" found favor with F. Orlin Tremaine of Astounding Stories, who published it in the December 1933 issue (note the Blue Eagle of the National Recovery Administration on the left side of the cover). While there's some truth to Derleth's assertion that the story lacks action, its central idea is powerfully evocative – so powerful that it more than compensates. In my opinion, this is true of much of Smith's oeuvre and it's the reason why I consider his yarns every bit as inspirational as those of more celebrated pulp fantasists like Howard or Lovecraft.

"The Demon of the Flower" takes place on another world, a planet called Lophai, whose plants and flowers were utterly unlike those of Earth.

Many were small and furtive, and crept viper-wise on the ground. Others were tall as pythons, rearing superbly in hieratic postures to the jeweled light. Some grew with single or dual stems that burgeoned forth into hydra heads, and some were frilled and festooned with leaves that suggested the wings of flying lizards, the pennants of faery lances, the phylacteries of a strange sacerdotalism. Some appeared to bear the scarlet wattles of dragons; others were tongued as if with black flames or the colored vapors that issue with weird writhings from out barbaric censers; and others still were armed with fleshy nets or tendrils, or with huge blossoms like bucklers perforated in battle. And all were equipped with venomous darts and fangs, all were alive, restless, and sentient.

Of all these sentient plants, the most important was the "supreme and terrible flower known as the Voorqual, in which a tutelary demon, more ancient than the twin suns, was believed to have made its immortal avatar." The Voorqual grew atop the summit of a step-pyramid in the equatorial city of Lospar, where also dwelled King Lunithi. Lunithi also served as the leader of a priesthood that served the nourishment of the Voorqual.

This nourishment consisted first of "a compost in which the dust of royal mummies formed an essential ingredient," but it also consisted of the lifeblood of one of its priesthood, chosen each year at the summer solstice by the demon within the ancient and monstrous plant. This year, the Voorqual had chosen the priestess Nala as the sacrifice, a young woman who was to be wed to King Lunithi in a month's time. Needless to say, Lunithi was none too pleased by this turn of events and impiously begins to ponder how he "could cheat the demon of its ghastly tribute."

Amid such reflections, Lunithi remembered an old myth about the existence of a neutral and independent being known as the Occlith: a demon coeval with the Voorqual, and allied neither to man nor the flower creatures. This being was said to dwell beyond the desert of Aphom, in the otherwise unpeopled mountains of white stone above the habitat of the ophidian blossoms. In latter days no man had seen the Occlith, for the journey through Ayhom was not lightly to be undertaken. But this entity was supposed to be immortal; and it kept apart and alone, meditating upon all things but interfering never with their processes. However, it was said to have given, in earlier times, valuable advice to a certain king who had gone forth from Lospar to its lair among the white crags.

In his grief and desperation, Lunithi resolved to seek the Occlith and question it anent the possibility of slaying the Voorqual. If, by any mortal means, the demon could be destroyed, he would remove from Lophai the long-established tyranny whose shadow fell upon all things from the sable pyramid.

When the king at last comes upon the Occlith, which looked like " a high cruciform pillar of blue mineral," he prostrated himself before it and asked its counsel concerning the Voorqual.

"It is possible," said the Occlith, "to slay the plant known as the Voorqual, in which an elder demon has its habitation. Though the flower has attained millennial age, it is not necessarily immortal: for all things have their proper term of existence and decay; and nothing has been created without its corresponding agency of death... I do not advise you to slay the plant... but I can furnish you with the information which you desire. In the mountain chasm through which you came to seek me, there flows a hueless spring of mineral poison, deadly to all the ophidian plant-life of this world..."

The Occlith went on, and told Lunithi the method by which the poison should be prepared and administered. The chill, toneless, tinkling voice concluded:

"I have answered your question. If there is anything more that you wish to learn, it would be well to ask me now."

Lunithi dared not ask any further question, but instead set off to find the poison of which the Occlith had spoken and then to return to Lospar to save his betrothed. This being a Clark Ashton Smith story, I do not think it will surprise anyone to learn that things do not go quite as the priest-king had planned.\

"The Demon of the Flower" is a short and no-nonsense story that nevertheless presents its fanciful, almost fairytale-like narrative, in lovely, hypnotic language. It's one of those stories that almost demands to be read aloud. More importantly, its central idea – a world where sentient plants ruled "and all other life existed by their sufferance" is a potent and frankly creepy one, all the more so when one reads the details of the annual choosing the Voorqual's sacrifice. It's well worth a read if you have twenty or thirty minutes to spare.

November 12, 2022

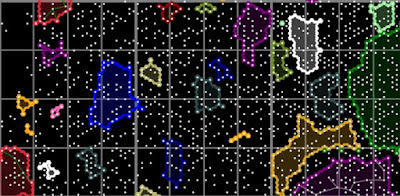

Frontiers of Adventure

Thanks to Traveller MapWhen Traveller first appeared in 1977, GDW's game of science fiction adventure in the far future followed the model of Original Dungeons & Dragons in being a generic ruleset without an explicit setting. Of course, like OD&D, Traveller's rules included within them assumptions that laid for the groundwork for an implied setting. An illustrative example of what I'm talking about is the relative slowness of interstellar travel and the concomitant lack of a separate (and faster) form of interstellar communications. Thus, Traveller may not have included its own integral setting, at least initially, but its rules certainly pushed referees in certain directions as they created their own settings, much as OD&D had done before it.This situation didn't last long, though. Starting with the appearance of Mercenary in 1978, GDW started including references to "the Imperium" in its products. Initially, the Imperium was just a stand-in for any remote interstellar government of the sort that Traveller's rules implied. By the time of the release of

The Spinward Marches

in 1979 (if not before), it had started down the path that would soon make it the explicit setting of the game. From my conversations with the late Loren Wiseman and others, this shift in emphasis was one that players of the game wanted, based on feedback that GDW received from them. I can hardly blame them for catering to their buying public.

Thanks to Traveller MapWhen Traveller first appeared in 1977, GDW's game of science fiction adventure in the far future followed the model of Original Dungeons & Dragons in being a generic ruleset without an explicit setting. Of course, like OD&D, Traveller's rules included within them assumptions that laid for the groundwork for an implied setting. An illustrative example of what I'm talking about is the relative slowness of interstellar travel and the concomitant lack of a separate (and faster) form of interstellar communications. Thus, Traveller may not have included its own integral setting, at least initially, but its rules certainly pushed referees in certain directions as they created their own settings, much as OD&D had done before it.This situation didn't last long, though. Starting with the appearance of Mercenary in 1978, GDW started including references to "the Imperium" in its products. Initially, the Imperium was just a stand-in for any remote interstellar government of the sort that Traveller's rules implied. By the time of the release of

The Spinward Marches

in 1979 (if not before), it had started down the path that would soon make it the explicit setting of the game. From my conversations with the late Loren Wiseman and others, this shift in emphasis was one that players of the game wanted, based on feedback that GDW received from them. I can hardly blame them for catering to their buying public.More to the point, I've always loved the Imperium. By the time I began playing Traveller, there was very little sense that the game had ever been a generic ruleset without an explicit setting and I was quite content with this situation. That said, most of GDW's efforts in describing the Imperium were focused on its frontiers, sectors of space like the aforementioned Spinward Marches and the Solomani Rim. Likewise, the various third parties licensed by GDW to produce their own materials setting set in and around the Imperium tended to follow their lead, whether they were Judges Guild or Gamelords or FASA. By comparison, there was little or no material set in the core sectors of the Imperium.

I was reminded of all this recently because a good friend of mine offered to referee a Traveller campaign and he chose to set it in the Crucis Margin sector, in the region trailing the Imperium. The sector is in close proximity to the Imperium, as well as the Solomani Confederation, the Two Thousand Worlds, and the Hive Federation but none of these major interstellar powers has any presence here. Instead, there are multiple smaller governments, usually no more than a dozen worlds in size – the very same model I used in my Riphaeus Sector campaign.

I think it's pretty obvious why this is such an attractive set-up for a RPG campaign setting: frontiers are where adventures happen. Sometimes this is quite explicit. For example, there are The Keep on the Borderlands for D&D and Borderlands for RuneQuest, to cite just two very obvious examples. Back in the realm of science fiction, there's Star Frontiers and Star Trek , whose televisual inspiration dubbed space the final frontier. I rather suspect that one of the reasons that RPGs set in the modern day generally do poorly is that most of them lack a clear frontier and thus the possibilities for adventure are more limited. The only exceptions I can think of are horror games like Call of Cthulhu or Vaesen , where I would argue that the supernatural (or at least extramundane) constitutes a frontier of sorts.

If we turn back to Traveller, it would seem that GDW learned this lesson as well. Most of the editions of the game after its initial one were explicitly set not just in the Imperium setting but during a time when there were lots more frontiers. MegaTraveller (1987) shattered the Imperium in a civil war that resulted in the foundation of antagonistic successor states, while Traveller: The New Era (1993) takes place when much of interstellar civilization is rebuilding in the aftermath of that same civil war. I suspect a big part of the appeal of post-apocalyptic games like Gamma World is the way they take a staid, familiar setting, like Earth, and fill it with frontiers again.

None of this is to suggest that it's impossible to have a satisfying roleplaying game campaign set in the core areas of a stable society, but, as I scan my bookshelves, looking at the games I have played most often, I see few obvious examples of them. I don't think that's mere coincidence.

November 11, 2022

By Any Other Name

Like most people who got into the hobby in the late 1970s or early '80s, my first roleplaying game was Dungeons & Dragons. However, my second RPG was Gamma World and one of the things that struck me about it at the time was that it didn't have a special name for its referee. For some reason, I'd assumed that, just as D&D has a Dungeon Master, Gamma World would have something equally distinct, perhaps a Mutant Master. That it didn't was a bit of a disappointment.

I don't know where I'd gotten the idea that the referee in every RPG should have a special name for its referee, because most of the games I encountered in those first years after I'd discovered D&D did not. Generally, they used Game Master, Referee, or even Judge. There were exceptions, of course, like Top Secret's Administrator and Call of Cthulhu's Keeper of Arcane Lore, but they were actually few and far between.

Are there any other notable examples of RPGs from prior to 1990 or so that use an unusual name for their referees?

November 10, 2022

When Anton Met Ashton

(left to right): Robert Barbour Johnson, George F. Haas,

(left to right): Robert Barbour Johnson, George F. Haas,Clark Ashton Smith, Howard Stanton LeveyOne of the consistent contentions of this blog is that roleplaying games bubbled up at the decades-long confluence of multiple streams of culture, both high and popular. Those streams are many and include not simply the works of pulp fantasy that are a particular preoccupation of mine but many more – and stranger – things besides. I thought about this when I stumbled across the above photograph, for reasons I'll explain shortly. I can find no precise date for it, but it seems likely to have been taken after 1954, when Clark Ashton Smith moved from his childhood home of Auburn, California to Pacific Grove following his marriage to Carolyn Jones Dorman.

Smith largely gave up the writing of fiction by 1937, the conclusion of a period of several years that saw the deaths of both of his aged parents, as well as his friends and colleagues, Robert E. Howard and H.P, Lovecraft. The last surviving member of the Three Musketeers of Weird Tales, he retreated into his secluded cabin to work on his poetry and sculpture. Despite his disengagement from the growing science fiction and fantasy scene that he'd helped to found, admirers – some from as far away as Japan – would nevertheless call on him, both in Auburn and then later in Pacific Grove.

The photo above was taken on the occasion of a visit by several of his admirers. On the far left is Robert Barbour Johnson. Johnson was an artist and writer of weird fiction, as well as a dedicated Fortean. Standing next to Johnson is George F. Haas. Haas is perhaps most famous nowadays as an early devotee of cryptozoology, specifically the hunt for Bigfoot. Next to Haas is, of course, CAS, with his signature blazer and cigarette holder. At the far right is Howard Stanton Levey, who was, among other things, a regular hanger-on in the science fiction and fantasy fan community of San Francisco. A few years later, Levey had renamed himself Anton LaVey and began to peddle Ayn Rand in devil horns as Satanism.

There is, of course, no record of what occurred during this visit, which is a shame. I would like to think that Smith, while outwardly gracious and gentlemanly as ever, would have seen right through a huckster like LeVay. In my mind, though, I'd like to believe that any attempt by LeVay to intimate he had knowledge of genuine diabolism would have been met with skepticism akin to Christopher Lee's reply to Peter Jackson on the subject of what happens when a man is stabbed in the back. Of course, this was more than a decade before the founding of the Church of Satan, so the subject might not never have arisen. Still, a man can dream!

November 9, 2022

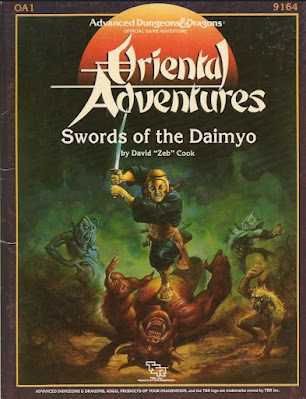

Retrospective: Swords of the Daimyo

Japanophilia was a significant pop cultural force in North America and Europe during the 1980s. This manifested not simply in the enjoyment of anime featuring giant robots but also in an increased interest in the history and legends of feudal Japan, an interest that no doubt built upon the already existing 1970s obsession with Asian martial arts. That Dungeons & Dragons would eventually embrace these interests would have surprised no one who had been paying attention to the matter. The first treatment of samurai in D&D appeared in issue #3 of Dragon (October 1976), for example, while ninja appeared in issue #16 (July 1978) – and both of these postdated the monk class from Blackmoor (1975). There was thus never any doubt that TSR would eventually publish a book like Oriental Adventures. The only question was why it had taken the company so long to do so.

Japanophilia was a significant pop cultural force in North America and Europe during the 1980s. This manifested not simply in the enjoyment of anime featuring giant robots but also in an increased interest in the history and legends of feudal Japan, an interest that no doubt built upon the already existing 1970s obsession with Asian martial arts. That Dungeons & Dragons would eventually embrace these interests would have surprised no one who had been paying attention to the matter. The first treatment of samurai in D&D appeared in issue #3 of Dragon (October 1976), for example, while ninja appeared in issue #16 (July 1978) – and both of these postdated the monk class from Blackmoor (1975). There was thus never any doubt that TSR would eventually publish a book like Oriental Adventures. The only question was why it had taken the company so long to do so.

Of course, releasing a rulebook devoted to adding classes, spells, magic items, and monsters inspired by Japanese legendry (and, to a much lesser extent, those of other Asian cultures) is one thing. Illustrating how to make good use of them in the context of D&D is another. Oriental Adventures devotes a mere six pages to sketching a fantasy setting – Kara-Tur – inhabited by the bakemono, hengeyokai, shukenja, and other Eastern additions offered by the rules. Despite its title, there are no sample adventures presented in OA, leaving referees and players alike to their own devices to figure out what to do with all the new material it provides.

That's where Swords of the Daimyo comes in. Written by David Cook, author of Oriental Adventures, and published in 1986, it consists of two 32-page booklets intended to provide referees with everything they need to kick off a campaign set in Kara-Tur – or, more specifically, a small portion of it called Kozakura. The island of Kozakura is a clear analog to medieval Japan's Warring States period, when rival warlords openly vied with one another for control of the empire. This makes it a good fit for the default assumptions of D&D, with adventurers wandering about freely. Indeed, I'd go so far as to say that this sort of situation makes even more sense than many D&D settings, where the social order is still largely intact.

The first of the two integral booklets details three adventures set in Kozakura. The first of these, "Over the Waves We Will Go," is optional and intended only for referees who wish to transport characters from an existing Western-style campaign into the world of Oriental Adventures. As its title suggests, the scenario focuses on a seagoing journey to the lands of Kara-Tur. As adventures go, it's quite unusual, in that it focuses primarily on the ins and outs of a long voyage across the ocean. There's a large – and somewhat impressionistic – map divided into encounter areas the characters must navigate. The referee then uses their position to determine not only how long it takes them to cross the distance to Kozakura, but also what set or random encounters they may have. Equally important is the "mutiny rating" of the crew, a value that goes up or down based on how well the characters do along the way.

The other two scenarios can be played by either non-native or Kozakuran characters, with the module providing eight sample PCs generated using the Oriental Adventures rules. These characters are surprisingly useful, even if you're not using them directly in play, since they provide little details about both the setting and what "typical" OA characters might be like, especially when compared to those of standard AD&D. Of most immediate interest is that several of them come from families or clans that are immersed in the Kozakuran setting. They're not rootless wanderers without any social ties and that, I think, is key to understanding how an OA campaign might differ from many, if not most, Western campaigns.

The second booklet provides lots of information on the Miyama province of Kozakura, the location of the adventures presented in the first book. The information includes many of the usual things, like history, geography, and politics. Much more interesting – and useful – is a hex-by-hex gazetteer that includes lots of little adventure seeds for the referee to develop as needed. Coupled with the large number of maps, both large and small scale, it's an excellent primer for a neophyte referee looking to get a better sense of just Kozakura is like and the kinds of scenarios that might take place on the island. In many ways, it's the more useful of the two booklets, since it provides the referee with the tools he'll need to keep his campaign going.

When it was released, I was very happy to have a copy of Swords of the Daimyo, since it offered a solid collection of ideas and aids for use with Oriental Adventures. I'd already had some experience with Bushido by this point, but it was good to have access to the additional resources this module provided. Moreoever, Oriental Adventures assumes a more strongly fantastical world than does Bushido, so the guidance Swords of the Daimyo provided in this regard was quite helpful. I made good use of it when I was in college and ran a short-lived but memorable OA campaign with my friends. Looking back on it now, I recognize that, even at this late a date, TSR was still producing some solid material that hadn't wholly bought into the principles of the Hickman Revolution. Whatever its shortcomings, Swords of the Daimyo feels like a throwback to the Golden Age of D&D rather than a product of the mid-Silver Age and that's more than good enough in my book.

November 8, 2022

Free Lord Ksárul Now!

From the letter page of White Dwarf #57, some Tékumel-related postal humor:

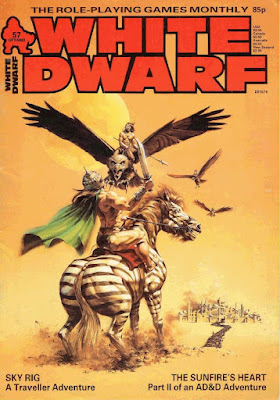

White Dwarf: Issue #57

Issue #57 of White Dwarf (September 1984) features a cover by an artist credited only as Tweddell. The image is certainly an eye-catching one that, for me at least, evokes some of the pre-vanilla strains of fantasy that flourished prior to the 1980s. Perhaps it's the weird mounts of the two warriors that does, I don't know. In any case, I find myself strangely fond of this particular cover, more so than I would have expected.

Issue #57 of White Dwarf (September 1984) features a cover by an artist credited only as Tweddell. The image is certainly an eye-catching one that, for me at least, evokes some of the pre-vanilla strains of fantasy that flourished prior to the 1980s. Perhaps it's the weird mounts of the two warriors that does, I don't know. In any case, I find myself strangely fond of this particular cover, more so than I would have expected. Ian Livingstone's editorial uses Games Workshop's release of its Judge Dredd and Doctor Who games as an opportunity to ponder the matter of licensed RPGs. He wonders why there are now so many games based on pre-existing characters and settings when Dungeons & Dragons, a generic and open-ended game without a direct media antecedent, remains the best-selling RPG. The matter of roleplaying games based on media properties is something I've thought a lot about over the years and re-reading Livingstone's brief comments on the matter have brought them to mind again. I may need to write a post about it in the coming days, if only to attempt to organize my own inchoate thoughts on the subject.

"Mind over Matter" by Todd E. Sundsted tackles the ins and outs of psionics in AD&D and other fantasy RPGs. By and large, the article's intended as advice to the referee and, on that level, is fine if uninspired. Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" is the usual collection of snarky reviews mixed with occasional praise, with the latter being heaped on Frederik Pohl's Heechee Rendezvous and Gordon Dickson's Lord Dorsai. Langford also takes the opportunity to tie his reviews into roleplaying games, when he uses the "Neanderthal ethics" of E.E. Smith's Subspace Encounter as a springboard for discussing the "moral bias" of adventure scenarios. He doesn't dwell on the topic at any length, however. His intent seems merely to have been to get referees (and players) to consider the matter rather than simply ignore it.

"Open Box" starts with a quartet of (mostly negative) reviews of Mayfair Role Aids releases: Elves (3 out of 10), Dwarves (3 out of 10), Dark Folk (3 out of 10), and Wizards (6 out of 10). While there's no question that most Role Aids books weren't very good, I can't help but feel the reviewer, Robert Dale, is being unduly harsh here. Much more positively reviewed is The Traveller Adventure, which receives a well-deserved 9 out of 10. Powers & Perils, a game whose mere existence continues to baffle me, is given a very generous 8 out of 10, largely, it seems, on the basis of how much of its contents might be adapted to other fantasy RPGs. Finally, James Bond 007 is given a mediocre 6 out of 10.

"Sky Rig" by Paul Ormston is a Traveller scenario with a classic set-up: the characters are tasked to investigate why contact was lost with an orbital refinery in a gas giant. It's a fun little adventure in an unusual locale and I made good use of it in my youth. "For the Blood is the Life" by Dave Morris offers up an alternative to the traditional Gloranthan vampire in the form of the vampyr (and demi-vampyr). Morris's complaint is that, mechanically, there's no good reason for Gloranthan vampires to drain blood, which he considers an important part of the lore of the creature, hence the alternative version he offers, whose continued existence depends on blood.

The second article in the "Night's Dark Agents" series by Chris Elliott and Richard Edwards provides game mechanics for better integrating ninjas AD&D, RuneQuest, and, believe it or not, Bushido. Once again, I note how quintessentially 1980s it is to have an article like this in a gaming magazine. "The Life of a Retired Wizard" by Lewis Pulsipher is a consideration of what magic-users, whatever their level, might do with themselves after they stop adventuring. Though short, it's a thoughtful article whose intent seems to be to encourage referees to give some thought to the question of how magic works and is used in his setting.

Part 2 of "The Sunfire's Heart" AD&D adventure by Peter Emery is as good as the first part. The scenario has some excellent maps and challenging encounters, as well as some delightfully old school elements, such as riddles that provide clues to the adventurers. This month's "Thrud the Barbarian" introduces readers to Eric of Bonémaloné and his demon sword Stoatbringer, while "Gobbledigook" and "The Travellers" continue to chug along somewhat less memorably. "The Staurni" by Andy Slack presents a version of the aliens from Poul Anderson's The Star Fox for use with Traveller.

"Majipoor Monsters" by Graham Drysdale details seven monsters for D&D drawn from the works of Robert Silverberg. Having never read Lord Valentine's Castle and its follow-ups, I can't really speak to the fidelity of these write-ups. "Racy Bases" by Gary Chalk and Joe Dever looks at how to improve the bases of miniature figures. I found the article oddly compelling, even though I've never been much of a miniatures user (let alone painter). "Words of Wisdom" by Kiel Stephens concludes the issue with some thoughts on a handful of new and unusual ways to make use of D&D spells, such as using levitate as an attack against an unwilling target or magic mouth as an alarm.

There's a lot to like about this issue of White Dwarf – or so I thought when I first read it all those decades ago. Even now, I think both "Sky Rig" and "The Sunfire's Heart" are well done and could easily imagine making use of them in a fantasy or science fiction RPG I were refereeing. That's more than I can say about many issues of this or any other gaming magazine I've owned over the years.

November 7, 2022

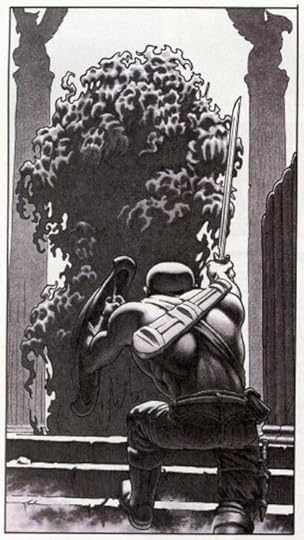

Master of Light and Dark

Dave Trampier sometimes catches some flak in old school circles for the supposed "sameyness" of his art, particularly the faces of any people who appear in his work. While I don't agree with that criticism, I understand it. For me, though, Tramp's real strength lay in his use of light and dark, a talent of which I was reminded when I looked at this panel from the installment of Wormy that appeared in issue #100 of Dragon (August 1985). What an amazing piece of work!

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers