James Maliszewski's Blog, page 90

December 13, 2022

RIP Kim Mohan (1949–2022)

Kim Mohan as caricatured by Phil FoglioI've now seen reports that Kim Mohan, former editor-in-chief of Dragon, has died at the age of 73. Mohan was also the author or editor of several gaming products from TSR, New Infinities, and West End Games, perhaps most notably the Wilderness Survival Guide for AD&D. By all accounts, he was a hardworking, creative, and, above all, kind man. His death marks the passing of yet another of our hobby's elders and he will be missed not just by those who knew and loved him, but by all those who were touched by his work.

Kim Mohan as caricatured by Phil FoglioI've now seen reports that Kim Mohan, former editor-in-chief of Dragon, has died at the age of 73. Mohan was also the author or editor of several gaming products from TSR, New Infinities, and West End Games, perhaps most notably the Wilderness Survival Guide for AD&D. By all accounts, he was a hardworking, creative, and, above all, kind man. His death marks the passing of yet another of our hobby's elders and he will be missed not just by those who knew and loved him, but by all those who were touched by his work.Rest in peace, Mr Mohan.

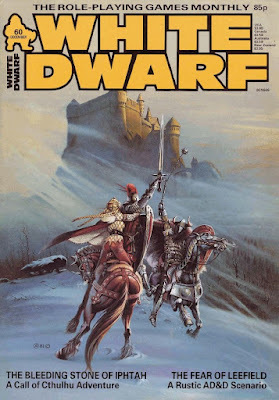

White Dwarf: Issue #61

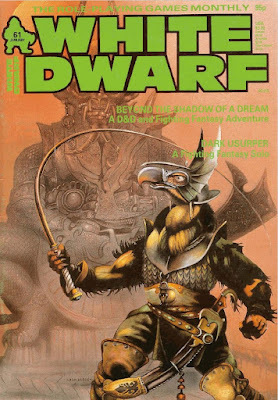

Issue #61 of White Dwarf (January 1985) has a very strange cover by Chris Achilleos. I'm not sure if the armored bird (?) man with a whip is supposed to be a hero or a villain. Perhaps the ambiguity is the point. In any case, it's certainly striking, if a bit confusing to a man of my limited imagination. In his editorial, Ian Livingstone announces that, starting next issue, WD will include regular columns devoted to both Call of Cthulhu and GW's own Golden Heroes. I recall CoC content being a staple of the magazine during the period when I was a subscriber, so this is no surprise. Likewise, by the mid-80s, Games Workshop was well on its way toward becoming more than just a distributor and publisher of UK editions of American games, so shining the spotlight on Golden Heroes makes a great deal of sense.

Issue #61 of White Dwarf (January 1985) has a very strange cover by Chris Achilleos. I'm not sure if the armored bird (?) man with a whip is supposed to be a hero or a villain. Perhaps the ambiguity is the point. In any case, it's certainly striking, if a bit confusing to a man of my limited imagination. In his editorial, Ian Livingstone announces that, starting next issue, WD will include regular columns devoted to both Call of Cthulhu and GW's own Golden Heroes. I recall CoC content being a staple of the magazine during the period when I was a subscriber, so this is no surprise. Likewise, by the mid-80s, Games Workshop was well on its way toward becoming more than just a distributor and publisher of UK editions of American games, so shining the spotlight on Golden Heroes makes a great deal of sense.Oliver MacDonald's "The Spice of Life" for RuneQuest offers an expansion of the alchemy rules in game's rulebook. It's fine for what it is, though, in my opinion, it focuses far too much on the details of the Alchemists Guild than it does on the products of its members. I'd personally have preferred more alchemical substances than the article provides, but that's a matter of taste, I suppose.

"Open Box" kicks off with a review of the Dungeons & Dragons Companion Set, to which the reviewer gives a very fair 7 out of 10. Also reviewed is Pacesetter's Timemaster RPG (7 out of 10) and an adventure for it, Crossed Swords (7 out of 10). Pacesetter's Chill is here too, scoring 7 out of 10, along with the scenario Village of Twilight, which only nets 6 out of 10. The much more obscure Witch Hunt from Statcom Simulations receives 5 out of 10 because of its "limited" scope, with the reviewer suggesting that he couldn't "imagine players wanting to bother playing it more than once or twice." Finally, there's the review of The Adventures of Indiana Jones, which gets – and I know you'll be surprised by this – a 7 out of 10 (yes, yes, I know the reviewers weren't responsible for the numerical scores). More interesting to me is that the reviewer is quite evenhanded in his treatment of Indiana Jones, a game that's usually viewed with utter revulsion. While recognizing its limited nature, reviewer Adrian Knowles nevertheless found it fun and understood that it was written "entirely with a young market in mind."

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" is what it is, for good and for bad. For me, it's rough going, not merely because I frequently disagree with Langford's assessments of the books he reviews, but also because I find it difficult to muster much interest in brief reviews of books from more than three decades ago. This issue, he tackles, among other books, Robert Heinlein's Job: A Comedy of Justice, a book about which I have decidedly mixed feelings (like most of Heinlein's oeuvre). Reading Langford's comments, I found myself wondering what I'd think of Job were I to delve into again (not that that's very likely).

Part 3 of "Eye of Newt and Tongue of Bat" by Graeme Davis continues, focusing on rings, armor, and shields. Like its predecessors in the series, this one is fine – neither inspired nor terrible but perfectly adequate for its quixotic task of making the crafting of magic items in AD&D interesting. Andy Slack's "The Motivated Traveller," on the other hand, is much more intriguing. In it, he puts forward an alternate experience system for use with Traveller (and other SF RPGs, like Space Opera, Star Frontiers, and Universe). The system is built on the idea that each character can have up to three "motivations," such as adept, altruist, hedonist, killer, miser, and so on. A character earns "victory points" (VP) based on his pursuit of his motivations, with success bringing him an increased "victory level" (VL) that brings with it reputation and influence. Slack's system is really only an outline, but it's an interesting one that might work well in games that are about more than fighting and looting (not that there's anything wrong with that).

Ian Marsh's "Beyond the Shadow of a Dream" is a fantasy scenario that's remarkable for the fact that it is dual-statted for both Fighting Fantasy and D&D. However, it's not a programmed adventure but instead a traditional one that requires a referee to play. The scenario takes place in an unnamed city and involves the hunt for a youthful storyteller who's gone missing after appearing several nights, to great acclaim, in a local inn. The characters are tasked with unraveling the mystery of what happened to the storyteller. It's a surprisingly moody and expansive adventure that includes lots of interesting details, not to mention twists and turns.

Meanwhile, "The Dark Usurper" by Jon Sutherland and Gareth Hill is a straight-up, 104-entry Fighting Fantasy solo adventure. The player assumes the role of a knight wrongly imprisoned, who must escape the tower where he is held – fairly conventional stuff. Simon Burley's "Days of Future Past" is the final part of his article looking at setting up a superhero campaign. This time, he focuses on how on to make use of adventure modules for other games (and genres), converting them to the conventions of superheroism. It's an admittedly odd approach and one I wouldn't have expected, but I think Burley does a good job with it.

"All Creepies Great and Small" is a collection of new bugs for use as D&D monsters by Russell May. Most of these are wholly imaginary insects rather than simply being giant versions of terrestrial arthropods, though we do get a few real-world examples, like the giant mosquito. I'm a well-known fan of vermin monsters, so this article definitely caught my fancy. "Treasures" is a collection of four unique magic items for RuneQuest. They range from the relatively mundane (stones that glow in the dark) to the mythological (fang warriors who spring from hydra's teeth) to the epic (the helm of a hero of old). I'm also a sucker for unique magic items, so I enjoyed this article as well.

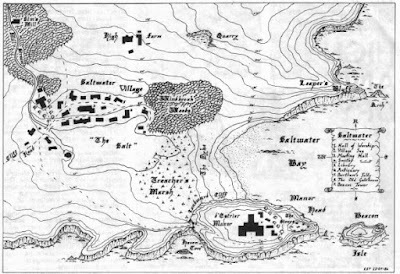

"Prize Competition" announces an adventure design competition. Entrants are to use a map (see below) provided by White Dwarf and then write a 4000-10,000-word scenario for a game of their choosing. The winner's submission will be published and he will receive a cash prize of £150.

I'll be curious to see the winning entry.

I'll be curious to see the winning entry."High and Dry" by Gary Chalk and Joe Dever looks at dry-brushing techniques for miniatures. As usual, the article is accompanied by lots of color illustrations, which is a delight to a guy like me, whose painting skills have always been poor. The issue also includes "Gobbledigook," "Thrud the Barbarian," and "The Travellers." Needless to say, I enjoyed them all, particularly "Thrud," which pokes fun at the well-worn trope of a weakling spending years developing his body and unarmed fighting skills to seek vengeance against those who mocked him. Mind you, "The Travellers" is great this issue too, as it continues to parody every science fiction franchise Mark Harrison can think of.

All in all, White Dwarf continues to impress. The magazine is now in a very comfortable spot, with a very diverse coverage of games for every taste.

December 12, 2022

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Outlaws of Mars

Otis Adelbert Kline, despite having a very memorable name, is one of those authors of the Golden Age of the Pulps that almost no one remembers today. To some extent, that's understandable, since his most successful stories are often erroneously described as being little more than rip-offs of the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs. The most well regarded of these – the two novels set on Mars – probably also suffer from not sharing a protagonist, unlike, say, the tales of John Carter to which they are unfavorably compared (or, for that matter, Kline's own Venus stories, all three of which feature the character of Robert Grandon).

Otis Adelbert Kline, despite having a very memorable name, is one of those authors of the Golden Age of the Pulps that almost no one remembers today. To some extent, that's understandable, since his most successful stories are often erroneously described as being little more than rip-offs of the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs. The most well regarded of these – the two novels set on Mars – probably also suffer from not sharing a protagonist, unlike, say, the tales of John Carter to which they are unfavorably compared (or, for that matter, Kline's own Venus stories, all three of which feature the character of Robert Grandon). I've previously written about the first of Kline's Martian novels, The Swordsman of Mars, and declared it better than its sequel, The Outlaws of Mars. Having just re-read the latter in preparation for today's post, I now wonder if my earlier judgment might have been mistaken. While both novels are breezily written and full of heroic exploits, Outlaw is notable in that its lead character, Jerry Morgan, is notably more fallible (and, therefore, more relatable) than Swordsman's Harry Thorne. Indeed, the initial action of Outlaws rests heavily upon the negative consequences of Morgan's leaping before he looked, as we shall see.

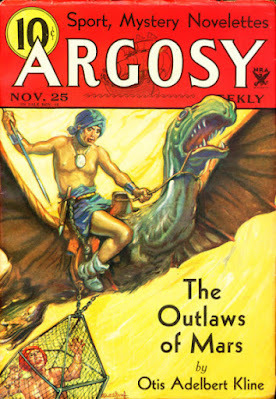

Like its predecessor, The Outlaws of Mars was originally serialized before being collected together under a single cover decades later. Also like its predecessor, the serial appeared in the pages of Argosy Weekly, starting with the November 25, 1933 issue and running for the next six issues. Though Kline was an assistant editor at Weird Tales (and had been since its premiere in 1922), none of his longer serials appeared in the Unique Magazine. I would imagine this was to avoid any appearance of favoritism, though several of his yarns did appear in WT's sister periodical, Oriental Stories.

The novel begins as Jerry Morgan, described as "a tall, broad-shouldered young man with steel-gray eyes and sandy hair," steps off a train at "the diminutive Pineville station." Morgan is in Pineville to visit his uncle (and former guardian), Dr. Richard Morgan, whom readers may remember as the eccentric scientist who enabled Harry Thorne to travel to the Red Planet in The Swordsman of Mars. Jerry believes his visit will be a surprise, but his uncle seems to be expecting him.

Jerry stared in amazement as he took his uncle's proffered hand. "Expecting me? Why, I told no one, and fully intended to surprise you. It sounds like thought-transference, or something."

"Perhaps you are nearer the truth than you imagine," replied the doctor, seating himself.

Setting aside his uncle's cryptic remark, Jerry admits that "I've disgraced the family – dragged the name of Morgan in the dirt." Again, Dr. Morgan claims to know this already and again Jerry boggles at this. Morgan then proceeds to prove that he knows why his nephew has come by recounting, in precise detail, the unfortunate circumstances that led him to his doorstep. The long and short of it is that Jerry had been framed by a romantic rival so as to not only lose the affections of his fiancée but also to be cashiered from the army regiment in which he had served proudly up to now.

Needless to say, Jerry is astounded by how much his uncle knows.

"You have said, half in jest, that I appear to read your mind. Without realizing it, you have hit upon the truth. I do and have always read your mind, since the death of your parents placed you under my guardianship. I have never needed your letters or telegrams to inform me of your doings, because since the day when I first established telepathic rapport with you, I have been able at all times to tap the contents of your subliminal consciousness, which contains a record of all you have thought and done."

Rather than dwell on the uncomfortable – to modern readers anyway – implications of this secret telepathic rapport, Dr. Morgan instead reveals that he has recently, thanks to his telepathic contact with "the people of Olba, a nation on the planet Venus," constructed a spaceship that will enable humans to travel to Mars "in the flesh," in contrast to the more mystical means employed in the previous novel, The Swordsman of Mars. While he would like to go to Mars himself, the urgency of his other work has prevented this. Naturally, Jerry offers to go in his stead, to which his uncle readily agrees.

Though Jerry's primary purpose in traveling to Mars is as "a valuable scientific experiment" that will "increase the sum total of terrestrial knowledge," it has the added benefit of giving him "new scenes, new adventures, and forgetfulness – these and a chance to begin life over again." This theme of "starting over," being given the chance to leave behind a shattered past, is a common one in sword-and-planet stories, starting with A Princess of Mars. I suspect it plays a big part in the lasting appeal of the genre and may have held particular resonance with readers during the depths of the Great Depression.

Jerry's transit to Mars is far less interesting than what happens upon his arrival. He finds himself not far from a Martian city, whose inhabitants "did not show any marked difference from terrestrial peoples" beyond "their strange apparel and the fact that their chests were, on average, larger than those of Earth-men," this latter feature being a consequence of the thinner atmosphere of the Red Planet. Jerry observes that many of the city's buildings feature roof gardens. In one of these gardens, he sees an extremely beautiful woman – of course! – with "an ethereal beauty of face and form such as he had never seen on Earth, or even dreamed existed."

I could not blame anyone for assuming at this point that the criticisms of Kline as a mere Burroughs imitator are correct. Thus far, The Outlaws of Mars is little different from the sword-and-planet material cranked out by the ream after the publication of A Princess of Mars and its sequels. However, that assessment of the novel would, in my opinion, be mistaken. When Jerry introduces himself to the young Martian beauty, she is frightened and looks ready to flee. Confused, the Earthman looks around for an explanation and seemingly finds it in the form of a strange Martian beast leapt from behind the shrubbery of the garden with "a terrific roar" and "a yawning, tooth-filled mouth as large as that of an alligator."

In an act of chivalry befitting John Carter himself, Jerry slays the alien creature, believing he had saved her from danger.

At the sound of the shot the girl had sprung erect. For a moment she peered down at the fallen beast. Then, her eyes flashing like those of an enraged tigress, she turned on Jerry with a volley of words that were unmistakably scornful and scathing, despite the fact that he was unable to understand them.

Suddenly her hand flashed to her belt and came up with a jewel-hilted dagger. Jerry noticed that the blade straight and double-edged, with tiny, razor-sharp teeth. For a moment, he did not realize what she intended doing. But when she raised her weapon aloft and lunged straight for his breast, he caught her wrists just in time.

We soon learn that the animal Jerry had slain was, in fact, the beloved pet of Junia Sovil, daughter of the emperor of Kalsivar, the greatest kingdom of Mars. Worse still, the slaying of the dalf (as the animal is called) is a capital crime – and the people of Kalsivar believe in swift justice. Thus, our hero has barely stepped foot on Mars and he has already made an enemy of an imperial princess and found himself condemned to death. Jerry Morgan works fast!

Naturally, Jerry does not die only a few chapters into The Outlaws of Mars and indeed soon finds himself entangled in the vicious court politics of Kalsivar, but I was nonetheless charmed by the way that Kline kicked off his adventures on Mars. Jerry's ignorance of Mars and its customs and language cause him no end of headaches early on. Likewise, his headstrong nature and gentlemanly ideals lead him astray almost as often as they aid him. It's almost as Kline were playing with and commenting upon the conventions of the sword-and-planet genre, though I have no evidence that he did so intentionally.

Regardless, The Outlaws of Mars is a fun, fast read, filled with plenty of pulpy action and dastardly deeds. To call it a classic would be overstating its simple virtues, but virtues they are nonetheless. I was very glad to have had the opportunity to re-read this and I recommend it to anyone who enjoys sword-and-planet stories.

December 9, 2022

What Price Glory?!

Last week, I wrote about Sir Pellinore's Game, an obscure 1978 RPG, whose existence I'd been alerted to by a couple of my regular correspondents. Like many (most?) people, I'd never heard of Sir Pellinore's Game, let alone knew that it had three different editions over the course of its existence. Fortunately, Precis Intermedia has made the game available again, in both print and PDF form. I don't know how many people will actually play the game, but there's no question that it's an invaluable resource for learning about the history of the RPG hobby.

Last week, I wrote about Sir Pellinore's Game, an obscure 1978 RPG, whose existence I'd been alerted to by a couple of my regular correspondents. Like many (most?) people, I'd never heard of Sir Pellinore's Game, let alone knew that it had three different editions over the course of its existence. Fortunately, Precis Intermedia has made the game available again, in both print and PDF form. I don't know how many people will actually play the game, but there's no question that it's an invaluable resource for learning about the history of the RPG hobby.

Now, I've been alerted to the fact that Precis Intermedia is preparing to make another obscure RPG from the 1970s available once: What Price Glory?! Written by John Dankert and James Lauffenberger, What Price Glory?! first appeared in the same year as Sir Pellinore's Game, 1978. Needless to say, this game is also unknown to me, so its imminent re-release is of great interest.

December 8, 2022

Tedium and the Limits of Simulation

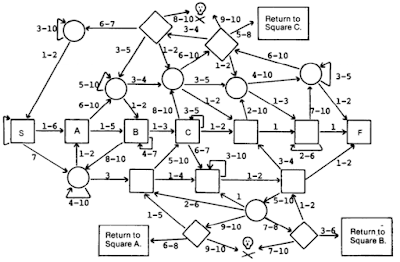

If you're a fan of the first edition of Gamma World (or, for that matter, Expedition to the Barriers Peaks), you'll immediately recognize the flowchart above. It's used to simulate a character's attempts to discern the use and operation of a technological artifact. The way it works is relatively straightforward. A token is placed on the square marked "S." Every hour of game time, a player rolls 1d10 up to five times to represent his character's efforts to puzzle out the workings of a piece of high-tech device. The roll is modified by his character's Intelligence score (and the presence of others helping him), The goal is to advance through the flowchart to reach the square marked "F," which indicates success in figuring out how the artifact works. Along the way, there's even the potential that these attempts might result in damage to the character and/or his companions, represented by the skull and crossbones symbols.

I've used this chart or ones like it many times in the past, since figuring out how to operate the tools of the Ancients is an important part of the fun of Gamma World. However, what I noticed is that the fun very quickly dissipates. After a half-dozen or so uses of the chart, the whole process ceases to be enjoyable and simply becomes tedious. I suspect I'm not the only one who felt this way, because the second edition of Gamma World, published in 1983, abandoned the use of these flowcharts entirely, opting for a different system that still involves a lengthy series of die rolls. Having made use of it as well, I can only say that I didn't find it any more consistently fun to use than the flowcharts.

I bring this up not to knock either system. Both are, in my opinion, valiant attempts to present a relatively simple method of simulating something that should be an important part of any post-apocalyptic RPG setting. Unfortunately, they fail – or, at least, they fail to do so in a way that holds up after more than a few uses. This, to mean, is an example of something that most roleplaying games struggle with in one place or another, namely the limits of simulation.

I've been thinking about this over the last week or so, after re-reading the last two issues of White Dwarf, which include details of a system for crafting magic items. I think most people would agree that the making of a magic item, especially something as impressive as a magic sword or a staff, should be an involved and difficult process, one that requires time, effort, and significant resources. Ideally, it should also be the foundation of many sessions of engaging activity by the player characters. In practice, though, I've generally found the opposite. Rather than being engaging, they've been enervating, often to the point where a player eventually decides that it's simply not worth all the effort.

That's a real shame. On the other hand, it's not an uncommon problem in many (probably most) RPGs of my acquaintance. There are many activities that, from a "dramatic" point of view, which is to say, from the perspective of a character living within a given imaginary setting, ought to be both significant and compelling. Yet, these are quite hard to simulate within a roleplaying game without bogging gameplay down in tedious detail. Research, whether of forgotten lore or the mysteries of spellcraft, is another example of the kind of thing of which I'm thinking. Poring over a blasphemous tome to unlock its secrets is a momentous endeavor for a character, but how best to handle it via game rules?

I suspect there is no single answer to that or any other question. Naturally, each player has varying degrees of interest and indeed tolerance for devoting precious game time to the simulation of certain activities. What seems tedious to one might well represent the epitome of pleasure for another. We see this all the time in debates over, for instance, how complex and detailed combat ought to be. For some, D&D's very abstract combat is more than sufficient, while, for others, nothing short of Rolemaster will do the trick. If that sounds like I'm waffling on the matter, I suppose I am, but that doesn't make it any less true.

Probably a Crazy Idea

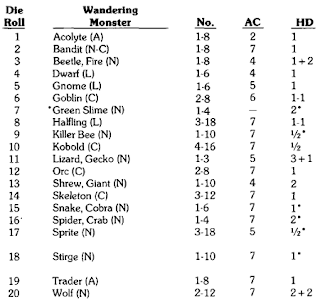

Among the most commonly forgotten and/or outright ignored rules in Dungeons & Dragons concerns wandering monsters. Once every 10 minutes of game time (in OD&D anyway; other editions of the game employ slightly different timescales), the referee rolls a six-sided die. A roll of 6 indicates that a wandering monster has appeared and one or more tables is consulted to determine their type and number. Even if one is not, as many contemporary referees seem to be, opposed to the idea of wandering monsters, it is very easy to let this rule fall by the wayside. I know this well, since it happens to be me regularly and has done since I first began to play D&D.

Among the most commonly forgotten and/or outright ignored rules in Dungeons & Dragons concerns wandering monsters. Once every 10 minutes of game time (in OD&D anyway; other editions of the game employ slightly different timescales), the referee rolls a six-sided die. A roll of 6 indicates that a wandering monster has appeared and one or more tables is consulted to determine their type and number. Even if one is not, as many contemporary referees seem to be, opposed to the idea of wandering monsters, it is very easy to let this rule fall by the wayside. I know this well, since it happens to be me regularly and has done since I first began to play D&D.I have a theory of why this is so. Unlike combat, each of whose rounds is played out individually, the 10-minute turn is much less directly concrete and the activities occurring during it are often abstracted rather than explicitly played out. As a result, turns "stick" less in the mind than combat rounds. This is compounded by the fact that often nothing of note happens during the course of a turn beyond simply advancing further down a passageway (and mapping it, of course). After enough turns of "nothing" happening, they tend to blend into each other and all but the most fastidious referee is going to lose track of in-game time.

This is why I propose rolling for wandering monsters once every 10 minutes (or whatever interval) of real time. This may seem radical, even nonsensical, but I think there's merit to the idea. For one, it's much easier (for me anyway) to consistently keep track of actual intervals of 10 minutes. Second, it's an additional incentive for the players to get things done. Over many years of refereeing, I have observed that players have a tendency to, as one of the players in my House of Worms campaign would say, faff about. However, given the limited time available for play, it behooves the players to stay focused on the matter at hand. The threat of a wandering monster roll every 10 real minutes might serve to light a fire under them, don't you think?

Obviously, this approach demands some degree of flexibility. For example, I wouldn't make a wandering monster roll in the middle of an active combat, even if the 10-minute mark had arrived. There are probably a handful of other circumstances where I'd be similarly inclined. However, the wandering monster rule exists, I suspect, as a pacing mechanism, as well as a potential drain of resources, which is why it's vital to ensure it's used rather than forgotten. If tying it to the real-world passage of time aids in this, I don't see an immediate problem in doing so (though I am sure my readers will find plenty of problems I've overlooked).

December 7, 2022

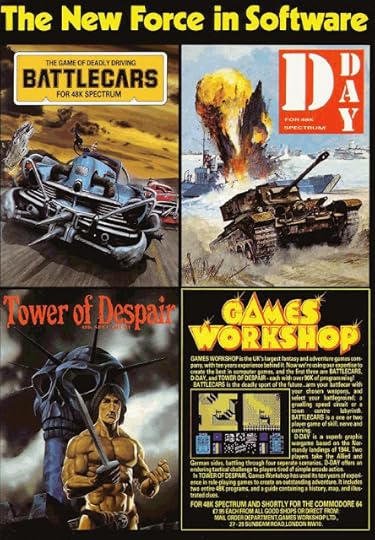

The New Force in Software

Issue #60 of White Dwarf magazine includes reviews of three Games Workshop computer games: Battlecars, D-Day, and Tower of Despair. Because they were all released for the Sinclair ZX Spectrum personal computer, which was, so far as I know, unavailable on this side of the Atlantic Ocean, I never saw (or played) the actual games themselves. Instead, I had to content myself with the advertisements that appeared in WD. Of the three, I'd have probably been most interested in Battlecars, because I always wanted to play the tabletop version of the game, but couldn't find a copy.

Did any readers own and/or play any of these games? If so, were they any good? Even after all these decades, I remain genuinely curious about them.

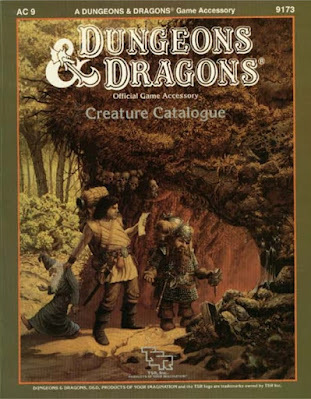

Retrospective: Creature Catalogue

Like a great many players of fantasy roleplaying games – probably most, come to think of it – I am a collector of monsters. The AD&D Monster Manual was the very first RPG product I ever bought for myself and, ever since then, new collections of monsters are usually an easy sell for me. Contradictorily, I'm also largely of the opinion that Dungeons & Dragons has too many monsters. If pressed, I'd walk back that assertion with a variety of cavils and equivocations, in part to justify my continued interest in new books of monsters – I am nothing if not self-justifyingly hypocritical.

Like a great many players of fantasy roleplaying games – probably most, come to think of it – I am a collector of monsters. The AD&D Monster Manual was the very first RPG product I ever bought for myself and, ever since then, new collections of monsters are usually an easy sell for me. Contradictorily, I'm also largely of the opinion that Dungeons & Dragons has too many monsters. If pressed, I'd walk back that assertion with a variety of cavils and equivocations, in part to justify my continued interest in new books of monsters – I am nothing if not self-justifyingly hypocritical. A good example of my hypocrisy comes in the form of 1986's Creature Catalogue. As an avid AD&D player, I believed myself obligated to ritually denounce "kiddie D&D," the truth is that there was a lot of excellent material published for that game line over the years of its existence. I clearly recognized this fact even at the time, because I'd often buy – and use – its modules, accessories, and even boxed sets in spite of my ostentatious repudiation of them.

I rationalized my purchase of the Creature Catalogue on the grounds that it was simply a monster book and that I might find some new foes in its pages with which to challenge the characters of my AD&D campaigns. To be fair to my youthful self, there was quite a lot of truth in my rationalization. It was indeed very easy to make use of elements of D&D – particularly its monsters – in AD&D, which is what I sometimes did. I did this to go effect with several of the monsters from Castle Amber, for instance, so the Creature Catalogue seemed like a solid investment.

In the end, though, I wound up being somewhat disappointed by my purchase. While the book presents more than 200 monsters, a little less than half of them were previously published elsewhere, generally in D&D modules. This was admittedly also true of my beloved Monster Manual II, but less so, since fewer appeared elsewhere and, there's no denying it, the overall quality was better. The monsters of the Creature Catalogue are simply not as good as those of the Monster Manual II, being by turns mundane or silly. There are naturally plenty of exceptions – with so many monsters, it would've been odd if there weren't – but my overall feeling remains that the Creature Catalogue is underwhelming.

The book is divided into distinct sections, each one of which is devoted to a type of monster. Thus, we get a section on animals, another on humanoids, and yet another on "lowlife," the term adopted for vermin monsters. The size of each section varies, with animals and, frustratingly, humanoids being quite numerous and undead – a favorite of mine – being comparatively less so. I say "frustratingly" with regards to humanoids, because it's long been my feeling that D&D could use a lot fewer intelligent, bipedal beings, but I realize this is an unpopular opinion.

Another disappointing aspect of the Creature Catalogue is how many "new" monsters it includes that are translations of pre-existing AD&D monsters into D&D terms. There are nightmares, hook horrors, umber hulks, and ropers, to name just a few. This is admittedly a continuation of a trend begun by the later Frank Mentzer-authored Companion, Master, and Immortal boxed sets, so I can't lay any special blame on the compilers of the Creature Catalogue (Graeme Morris, Phil Gallagher, and Jim Bambra) for it. However, I felt even in 1986 and feel more so now that one of the genuine virtues of the separate D&D line is that it had its own unique flavor distinct from that of AD&D. It was precisely this flavor that regularly got me to sheepishly buy D&D products in the first place. By "crossing the streams," so to speak, TSR was diluting what made D&D worthy in its own right.

The Creature Catalogue is not bad, so much as less good than I had hoped it would be. That's probably an unfair assessment born largely out of my own overblown expectation that it might be a Monster Manual III, but there it is. In general, I like monster books, even idiosyncratic ones like the Fiend Folio. Unfortunately, I can't count the Creature Catalogue among those for whom I have much fondness today and that's a shame. For all my adolescent snobbery, the Dungeons & Dragons line, at its best, offered another imaginative perspective on fantasy roleplaying that I found valuable; that's why I kept buying its releases. For the most part, the Creature Catalogue lacks that perspective. Instead, it feels tired and played out – and that's a genuine shame.

December 6, 2022

White Dwarf: Issue #60

Issue #60 of White Dwarf (December 1984) is another issue I remember well, largely because of its Call of Cthulhu scenario, which I rather liked at the time. I also remember finding its installment of "Thrud the Barbarian" – "Thrud Gets Sophisticated" – enjoyable as well, though, in my defense, I was only fifteen at the time and I was easily amused. Ian Livingstone's editorial focuses on the rising price of metal miniatures, which he fears will lead to figures becoming a luxury. He suggests that plastic miniatures might be a solution to this problem – which did, in fact, happen a few years later, the first plastic Citadel minis appearing in 1987 or thereabouts.

Issue #60 of White Dwarf (December 1984) is another issue I remember well, largely because of its Call of Cthulhu scenario, which I rather liked at the time. I also remember finding its installment of "Thrud the Barbarian" – "Thrud Gets Sophisticated" – enjoyable as well, though, in my defense, I was only fifteen at the time and I was easily amused. Ian Livingstone's editorial focuses on the rising price of metal miniatures, which he fears will lead to figures becoming a luxury. He suggests that plastic miniatures might be a solution to this problem – which did, in fact, happen a few years later, the first plastic Citadel minis appearing in 1987 or thereabouts."First Issues" by Simon Burley is the first part of a series about superhero roleplaying. As its title suggests, the article deals with what makes a good kick-off adventure for a superhero campaign. For its length (two pages), it offers solid advice and suggestions, along with some examples to illustrate its points. As these kinds of articles go, it's pretty good.

Dave Langford's latest "Critical Mass" column makes a few suggestions of books appropriate as Christmas gifts, some of which are high-priced, hardcover reprints of classic science fiction and fantasy books, often illustrated. Even more than usual, the column is mostly of interest historically rather than being of enduring interest. "Open Box," on the other, held my attention more fully. First up, we're treated to a review of Chaosium's ElfQuest, which its reviewer praises (9 out of 10) as "really the nicest RPG I have seen to give someone as a present." Dungeon Planner 2: Nightmare in Blackmarsh gets a solid 7 out of 10, while the first two Lone Wolf books – Flight from the Dark and Fire on the Water – score the same. Finally, there are reviews of three AD&D modules: The Sentinel (8 out of 10), The Gauntlet (7 out of 10), and Dragons of Despair (8 out of 10). The review of Dragons of Despair is notable for its belief that Tracy Hickman is a woman and its dislike for Clyde Caldwell's cover.

Part 2 of Graeme Davis's rules for magic item creation, "Eye of Newt and Wing of Bat," appears in this issue, with rods and potions being its subject this time. As I mentioned previously, I love the idea elaborate item creation rules, but most of them, this one included, are simply too fastidious ("The leg muscles of one axebeak. Simmer for 24 hours and stir in one powdered platinum arrow, minimum value 500gp.") to be workable in almost any campaign in which I have played. I don't know; perhaps others' experiences are very different from mine.

"The Bleeding Stone of Iphtah" by Steve Williams with Jon Sutherland is an excellent Call of Cthulhu scenario set in Jerusalem. Professor Foster is an archeologist being mentally manipulated by the Great Race of Yith, who seek to use him to open a gate that would enable them to escape destruction in the ancient past – but at the cost of mankind's survival in the 20th century. Fortunately, Foster is sufficiently strong willed that he is sometimes able, often with the aid of opium, to break free of the Great Race's control, thereby aiding the Investigators in thwarting their plans. Originally a convention adventure, it's short and focused, both of which are blessing in my opinion. I had fun with this in my gaming group of old and still think fondly of it.

"Boarding Actions" by Marcus L. Rowland is a look at the hazards of attempting to seize a starship in a science fiction RPG. Very well done, it's an extended examination of the tactics behind such an endeavor, from the perspective of both the would-be boarder and those who wish to repel them. The issue also includes new episodes of "Gobbledigook," "The Travellers," and "Thrud the Barbarian." Earlier, I alluded to "Thrud Gets Sophisticated," in which writer/artist Carl Critchlow attempts to (unsuccessfully) interject some elegance and urbanity into the adventures of the mighty-threwed barbarian – with predictable results.

Stuart Hunter's "The Fear of Leefield" is an AD&D adventure for characters of levels 3–5. In some ways, it's a fairly typical "rural village" in trouble, as the PCs must contend with mysterious events that are threatening the townsfolk. However, the scenario has an interesting twist in the form of its primary antagonist, a troublemaker who'd been exiled from Leefield in his youth and nursed a grudge against the place of his birth. Now a cleric in service to an evil deity (Bane the Black Lord), he is engineering a situation that will not only enable him to avenge himself upon the village but make him rich as well.

Stuart Hunter's "The Fear of Leefield" is an AD&D adventure for characters of levels 3–5. In some ways, it's a fairly typical "rural village" in trouble, as the PCs must contend with mysterious events that are threatening the townsfolk. However, the scenario has an interesting twist in the form of its primary antagonist, a troublemaker who'd been exiled from Leefield in his youth and nursed a grudge against the place of his birth. Now a cleric in service to an evil deity (Bane the Black Lord), he is engineering a situation that will not only enable him to avenge himself upon the village but make him rich as well. "Microview" reviews five computer games, three of them produced by Games Workshop. I had completely forgotten that GW was at one time involved in this part of the hobby. "Ars Arcana" by Kiel Stephens continues to provide commentary on AD&D spells, including clever uses for some of them. This series continues to be unexpectedly good and I'm amazed I hadn't recognized it before. "Felines, Fungi and Phantoms" presents four new monsters for Dungeons & Dragons, while "Bits of Fluff" does something similar for RuneQuest. Of the two, "Bits of Fluff" is better – and sillier – in that its monsters play with expectations in a way that a referee might find useful. Take a look and see what I mean:

Concluding the issue is "A Wash and Bush-up" by Gary Chalk and Joe Dever, an article about techniques for color washing miniature figures. As ever, I found the piece fascinating, probably because I was never a very good painter of figures (or indeed of anything else).

Concluding the issue is "A Wash and Bush-up" by Gary Chalk and Joe Dever, an article about techniques for color washing miniature figures. As ever, I found the piece fascinating, probably because I was never a very good painter of figures (or indeed of anything else).All in all, this is a solid issue, though not quite as good as I remember its being.

December 5, 2022

Wild, Fanciful, and Often Trippy

I don't think it's much of an exaggeration to suggest that the covers of science fiction and fantasy novels have gotten much less imaginative over the years. By the mid-1980s, the writing was already on the wall and the wild, fanciful, and often trippy covers that simultaneously attracted and frightened me as a kid were on the way out, to be replaced by an endless parade of Michael Whelan, Darrell K. Sweet, and their imitators. This is no knock against Whelan, who's a great artist, but there is a certain predictability to even his best work that I frequently find disappointing. Come to think of it, predictability might well be the defining characteristic of post-1970s SF and fantasy art, itself a reflection of the mainstreaming and commodification of these genres. (Cue my inevitable dig at much of the oeuvre of Larry Elmore.)

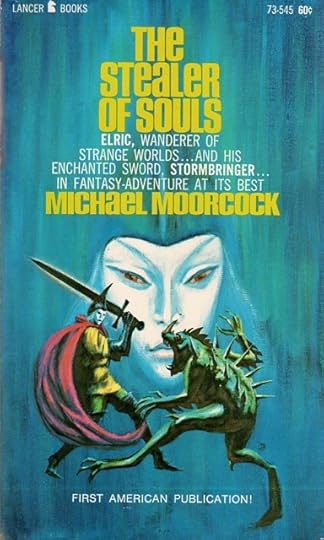

Science fiction and fantasy were still (relatively) fringe interests in the 1960s and '70s and the artwork from the period reflects that. Take a look at these three different covers to the paperback releases of Michael Moorcock's The Stealer of Souls, starting with the Lancer edition of 1967:

I have a certain fondness for this cover, because my local public library still had a copy of the book on one of its spinner racks, where I first saw it. Jack Gaughan, best known for his work on the unauthorized US printings of The Lords of the Rings, is the artist of this piece, depicting Elric in battle against the reptilian demon Quaolnargn, summoned by Theleb K'aarna as part of a plan to separate the Melnibonéan from Stormbringer, while the spectral visage of (I assume) Yishana watches.

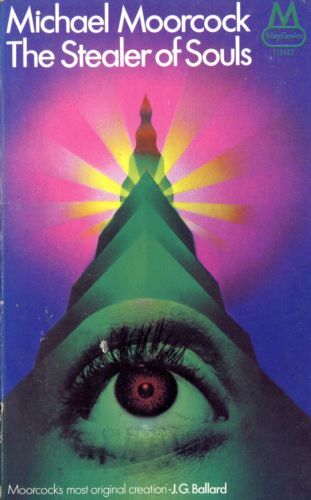

I have a certain fondness for this cover, because my local public library still had a copy of the book on one of its spinner racks, where I first saw it. Jack Gaughan, best known for his work on the unauthorized US printings of The Lords of the Rings, is the artist of this piece, depicting Elric in battle against the reptilian demon Quaolnargn, summoned by Theleb K'aarna as part of a plan to separate the Melnibonéan from Stormbringer, while the spectral visage of (I assume) Yishana watches. The 1968 Mayflower edition took a completely different tack:

Bob Haberfield, who'd go on to do the covers of many more Elric novels, is responsible for this one, which is a terrific example of the kinds of covers I remember well from my youth. Unlike Gaughan's Lancer cover, this one has no obvious connection to anything that occurs in the novelette. That's pretty much par for the course in the late '60s and throughout the 1970s.

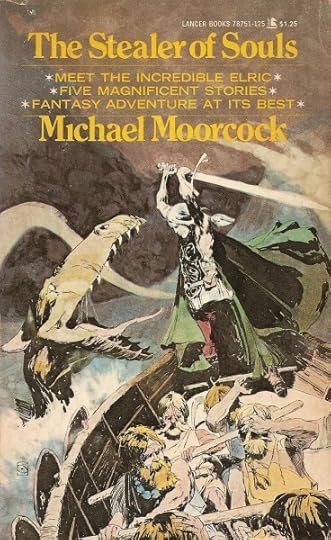

Bob Haberfield, who'd go on to do the covers of many more Elric novels, is responsible for this one, which is a terrific example of the kinds of covers I remember well from my youth. Unlike Gaughan's Lancer cover, this one has no obvious connection to anything that occurs in the novelette. That's pretty much par for the course in the late '60s and throughout the 1970s.Finally, there's another Lancer edition, this time from 1973.

This piece is by Jeff Jones, who had an extensive career as a comics illustrator and I think that shows in the cover. I'm not entirely sure what it depicts, though my guess is that it might be the naval assault on Imrryr from The Dreaming City, with the monster being a Melnibonéan dragon. In any case, it's a very dynamic piece that grabs the attention, which is exactly what the covers of science fiction and fantasy covers used to do.

This piece is by Jeff Jones, who had an extensive career as a comics illustrator and I think that shows in the cover. I'm not entirely sure what it depicts, though my guess is that it might be the naval assault on Imrryr from The Dreaming City, with the monster being a Melnibonéan dragon. In any case, it's a very dynamic piece that grabs the attention, which is exactly what the covers of science fiction and fantasy covers used to do.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers