James Maliszewski's Blog, page 87

January 10, 2023

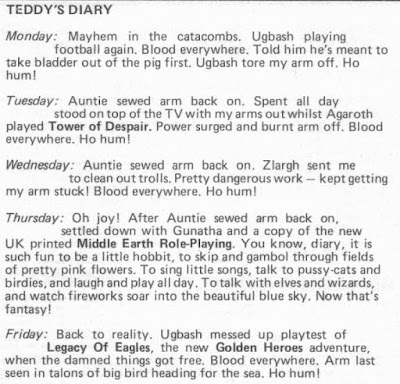

Teddy's Diary

White Dwarf: Issue #63

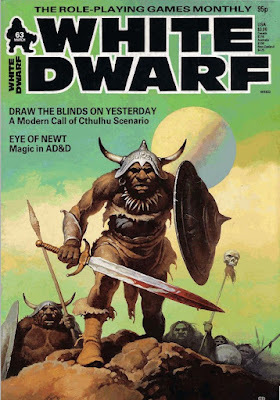

Issue #63 of White Dwarf (March 1985) is graced with a cover by Italian-born artist Gino D'Achille, who is probably most well-known for the work he did on the Ballantine editions of the Barsoom novels from 1973 (or the DAW Gor books, if that's more your preference). In his editorial, Ian Livingstone continues to ponder the state of the hobby, with particular emphasis placed on the peculiar ways that licensed properties are divvied up among companies. He notes, for example, that Games Workshop publishes the Doctor Who boardgame, while FASA publishes the RPG. He also notes that, while TSR publishes Battle System ("which sounds like Warhammer"), Citadel produces the official AD&D miniatures line. Livingstone's correct to note the oddity of this, but it's been pretty much par for the course for as long as the licensing of media properties has existed (and remains so to this day).

Issue #63 of White Dwarf (March 1985) is graced with a cover by Italian-born artist Gino D'Achille, who is probably most well-known for the work he did on the Ballantine editions of the Barsoom novels from 1973 (or the DAW Gor books, if that's more your preference). In his editorial, Ian Livingstone continues to ponder the state of the hobby, with particular emphasis placed on the peculiar ways that licensed properties are divvied up among companies. He notes, for example, that Games Workshop publishes the Doctor Who boardgame, while FASA publishes the RPG. He also notes that, while TSR publishes Battle System ("which sounds like Warhammer"), Citadel produces the official AD&D miniatures line. Livingstone's correct to note the oddity of this, but it's been pretty much par for the course for as long as the licensing of media properties has existed (and remains so to this day).The issue kicks off with "Arms and the Man" by Michael Holman, which builds on Andy Slack's article on vehicle combat in Traveller from White Dwarf #43. Holman introduces a number of new vehicle systems, including offensive ones, as well as an expanded vehicle combat procedure. It's all good stuff, though it highlights, as did Slack's article before it, just how much Traveller needed vehicular combat rules simpler than those in Striker.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" occasionally elicits my interest – not so this month, which is why I will pass over it without comment. Much more compelling to me is "Open Box," which very positively reviews Toon (9 out of 10), a game for which I have more affection than is probably justified. Also positively reviewed are a pair of videogames from Triffid Software, The Secret River and The Wizard's Citadel, which score a combined 8 out of 10 (somehow). I must admit I was surprised to see videogames reviewed in "Open Box." In the past, such things appeared in a separate column, "Microview," but I suspect it had been axed sometime prior to this. There's a side by side review of FASA's Star Trek III Starship Combat Game and Task Force's Star Fleet Battles Volume II. The comparison is not completely fair, since SFB Volume II is not a stand-alone product but a supplement. Even so, White Dwarf gives them 8 and 7 out of 10 respectively. Finally, there are reviews of the D&D modules, The Veiled Society (9 out of 10) and Quest for the Heartstone (4 out of 10). I'll be looking at the latter in a separate post tomorrow.

Part 5 of Graeme Davis's Eye of Newt and Wing of Bat concludes by tackling miscellaneous magic items. This is probably the least satisfying entry in the series, because it looks at only a small percentage of the miscellaneous items found in the Dungeon Masters Guide and presents no unified system for handling their manufacture. On the one hand, that's understandable, given the diversity of the miscellaneous magic items. However, the point of the series is to present a system to aid referees and players in adjudicating the creation of magic items. Without that, I think it's a little less useful than it might have otherwise been.

Carl Critchlow gives us the first part of "Thrud the Destroyer," which amusingly riffs off both the awful second Conan movie and The Magnificent Seven – fun stuff, as always. "The Travellers" and "Gobbledigook" are also enjoyable, though neither compares to this month's "Thrud." The third and final part of Jon Sutherland and Gareth Hill's "The Dark Usurper" Fighting Fantasy scenario appears in this issue, too. It's much like the previous parts, which is to say, passable as a solitaire scenario, though nowhere near as good as even an average full-length Fighting Fantasy book.

Much more compelling is Marcus L. Rowland's "Draw the Blinds on Yesterday," a Call of Cthulhu scenario set in the 1980s. The adventure concerns a missing flight between Athens, Grece and London, England, thanks to an unsuccessful attempt to summon Cthugha from Fomalhaut. Also involved is the last surviving Gorgon, an extraterrestrial species that is the origin of the myths of Medusa and her sisters. It's a delightfully bonkers scenario that somehow works, despite (because of?) its strange mix of elements.

"Setting the Scene" by Joe Dever and Gary Chalk is another fascinating miniatures-oriented article. This time, the authors look at the pitfalls of how best to make use of miniatures and scenery at the table. It's a topic I'd never really considered before, given my limited use of miniatures over the years. As usual, Dever and Chalk do a fine job of briefly laying out the problems and offering solutions, accompanied by useful color photographs. Every time I read one of their articles, I find myself deeply regretting that I never bothered to take up miniatures painting back when I still had the eyesight and hand-eye coordination to make a serious go of it. The folly of youth!

"Howzat!" by Mark Wilkinson, David Bailey, and Richard Bramah is humorous RuneQuest article that presents the rules (and game mechanics) for "elfball," a Gloranthan analog to cricket. There are even a few new spells for use during the game, like batting trance and team spirit, as well as additional spells for use by umpires. It's silly but fun, the kind of thing that I long considered a distinctive aspect of the UK game scene in the '80s. "A Not So Lonely Mountain" presents a pair of short scenarios involving the characters' ascent up a mountain – and the monsters they encounter along the way. I like this style of introducing new opponents in a RPG and wish it was done more often.

"Imperial Trooper" by Nic Weeks is look at the elite military forces of the Imperium of Traveller. It's mostly "fluff," in that it introduces no new rules or equipment for use with the game and, on that score, is good enough, though it does differ somewhat from GDW's own presentation of similar topics elsewhere. Concluding the issue is James Carmichael's "Help for the Hobbit Abroad," which presents some halfling-specific magic items, like pots of cooking and the pipe of the storyeller. (One of these years someone will figure out something to do with halflings that's more interesting than simply being Tolkien's hobbits with the serial numbers filed off – or, better yet, jettison them entirely!)

And so we come to the end of another issue of White Dwarf. As usual, it's a mixed bag, filled with a wide variety of material geared toward an equally wide variety of games. That was always White Dwarf's great strength when compared to Dragon and its relentless focus on Dungeons & Dragons. Of course, this sometimes meant that some issues of White Dwarf might not be as interesting to me as others, but that was a chance I was willing to take at the time. Re-reading these issues remains a delightful trip down memory lane; I look forward to the next one.

January 9, 2023

Blast from the Past

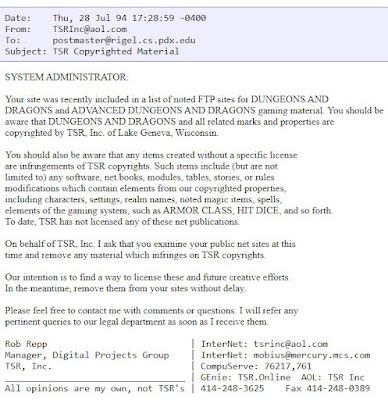

As many readers of this blog undoubtedly already know, Wizards of the Coast is rumored to have plans to "de-authorize" version 1.0a of the Open Game License. Leaving aside the big questions of whether the rumors are true and whether or not WotC has the legal authority to initiate such a monumental change, I find myself reminded of this:

That's the opening salvo in TSR's "war on the Internet" of the mid-1990s, when the company dubiously claimed that "any software, bet books, modules, tables, stories, or rules modifications which contain elements from our copyrighted properties, including characters, settings, realm names, noted magic items, spells, elements of the gaming system, such as ARMOR CLASS, HIT DICE, and so forth" were "infringements of TSR copyrights" unless they had been produced under license from TSR. Such belligerent and litigious behavior is what earned the company the nicknames T$R and They Sue Regularly.

That's the opening salvo in TSR's "war on the Internet" of the mid-1990s, when the company dubiously claimed that "any software, bet books, modules, tables, stories, or rules modifications which contain elements from our copyrighted properties, including characters, settings, realm names, noted magic items, spells, elements of the gaming system, such as ARMOR CLASS, HIT DICE, and so forth" were "infringements of TSR copyrights" unless they had been produced under license from TSR. Such belligerent and litigious behavior is what earned the company the nicknames T$R and They Sue Regularly. Ryan Dancey, the architect of the Open Game License, intended it, in part, to be a "laying down of arms" by Wizards of the Coast, an act of good faith to demonstrate that the then-new custodians of the world's first roleplaying game – this was 2000, remember – would not behave as TSR had done. It was also a way to safeguard the mechanics and ideas of D&D by "freeing" them, echoing Ted Johnstone's cri de coeur that "D&D is too important to leave to Gary Gygax." Dancey felt that D&D was too important to leave even to WotC, the company of which he was vice president at the time.

People more knowledgeable than I have a better handle on the legal and other ramifications of this possible turn of events. I highly recommend Rob Conley's series of posts on this topic, but many others have likewise written capably about it. Speaking personally, my concern is solely for the possible repercussions on the Old School Renaissance, a lot of whose foundational texts, such as OSRIC, Labyrinth Lord, and Swords & Wizardry , owe their existence to the OGL. If WotC is able to rescind even Version 1.0a of the OGL, despite previous assurances that this was impossible, it would send shockwaves throughout the hobby by overturning a state of affairs that has existed for more than two decades.

I suppose it's still possible that the leaked Version 1.1 of the OGL is merely a draft or even a trial balloon, but, even if that were true, I think this whole affair undermines the faith publishers have in the safe harbor that the OGL is supposed to provide them. Indeed, I would not be the least bit surprised if more than a few notable publishers decide to decouple their games from both the OGL and the D20 SRD. If so, we might see a return to the situation that existed in the '70s and '80s when publishers hid behind slightly altered terminology, such as Judges Guild's "hits to kill" instead of "hit points," in order to produce material broadly compatible with D&D without the need for a license (and royalty scheme) from TSR.

I will definitely have further thoughts on this matter in the coming days. If nothing else, I'll likely revisit the history of TSR's ham-fisted attempts to put the RPG genie back in the bottle, as well as take a look at just how much of D&D's purported intellectual property is obviously derivative of prior art. Interesting times!

Realism Is So Affordable

January 8, 2023

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Satyr

H.P. Lovecraft's career as a writer was seriously hampered by the fact that he would regularly withhold publication of his stories unless they were printed without alteration. His friend and colleague, Clark Ashton Smith, whose 130th birthday is this coming Friday – Friday the 13th, appropriately enough – had no such qualms. He understood well that, if one were to make a living as a writer of pulp fiction, one had to be both prolific and willing to acquiesce to even the most whimsical of editorial alterations. Consequently, Smith saw a phenomenal number of his stories published during his lifetime. Weird Tales alone published fifty-three of his tales, more even than Robert E. Howard, another of HPL's friends who understood the compromises necessary to make money as a writer.

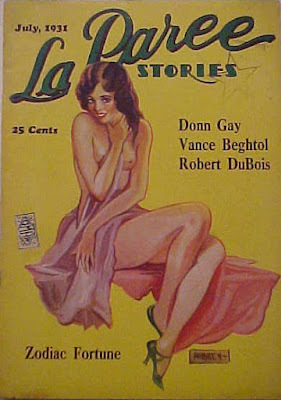

H.P. Lovecraft's career as a writer was seriously hampered by the fact that he would regularly withhold publication of his stories unless they were printed without alteration. His friend and colleague, Clark Ashton Smith, whose 130th birthday is this coming Friday – Friday the 13th, appropriately enough – had no such qualms. He understood well that, if one were to make a living as a writer of pulp fiction, one had to be both prolific and willing to acquiesce to even the most whimsical of editorial alterations. Consequently, Smith saw a phenomenal number of his stories published during his lifetime. Weird Tales alone published fifty-three of his tales, more even than Robert E. Howard, another of HPL's friends who understood the compromises necessary to make money as a writer.Smith's willingness to compromise extended not only to the content of his writing, but also to the markets to which he'd peddle his work. In the case of "The Satyr," one of the earliest stories in his Averoigne cycle, he made concessions to both. After repeated rejections from his usual publishers, who regarded it as "overly risqué," he sold it to La Paree Stories, a "spicy" pulp, whose pages were filled with erotic fiction and nude photography. Further, he changed the story's original ending to make it less ambiguous – a man's gotta eat, after all! The link above, sadly, goes to the version that appeared in the July 1931 issue of La Paree Stories; the original ending would not be restored until 2006.

As so many of Smith's tales do, "The Satyr" opens amusingly:

Raoul, Comte de la Frenaie, was by nature the most unsuspicious of husbands. His lack of suspicion, perhaps, was partly lack of imagination; and, for the rest, was doubtless due to the dulling of his observational faculties by the heavy wines of Averoigne. At any rate, he had never seen anything amiss in the friendship of his wife, Adele, with Olivier du Montoir, a young poet who might in time have rivalled Ronsard as one of the most brilliant luminaries of the Pleiade, if it had not been for an unforeseen but fatal circumstance.

The references to Pierre de Ronsard and La Pléiade place the story in the mid-16th century, which is later than most of his Averoigne stories, whose time period is more clearly medieval. Count Raoul, despite his usual trusting nature, somehow begins to suspect that perhaps there is something untoward in the relationship of his wife and the handsome young poet who composes "melodious villanelles and graceful ballades ... in celebration of Adele's visible charms."

it is hard to know just why M. le Comte became suddenly troubled concerning the integrity of his marital honour. Perhaps, in some interim of the hunting and drinking between which he divided nearly all his time, he had noticed that his wife was growing younger and fairer and was blooming as a woman never blooms except to the magical sunlight of love. Perhaps he had caught some glance of ardent or affectionate understanding between Adele and Olivier; or, perhaps, it was the influence of the premature spring, which had pierced the vinous muddlernent of his brain with an obscure stirring of forgotten thoughts and emotions, and thus had given him a flash of insight.

So, when he discovers that his wife and Olivier had recently left his chateau to go "for a promenade in the forest," he sets off after them – armed with his rapier.

Even ignorant of what her husband has planned, Countess Adele is worried.

Adele and Olivier had wandered beyond the limits of their customary stroll, and were nearing a portion of the forest of Averoigne where the trees were older and taller than all others. Here, some of the huge oaks were said to date back to pagan days. Few people ever passed beneath them; and queer beliefs and legends concerning them had been prevalent among the local peasantry for ages. Things had been seen within these precincts, whose very existence was an affront to science and a blasphemy to religion; and evil influences were said to attend those who dared to intrude upon the sullen umbrage of the immemorial glades and thickets.

Olivier, however, is not concerned, claiming that Adele's worries are based on "stories to frighten babes and beldames." He reassures her, "There is enchantment here, but only the enchantment of beauty." The pair proceed deeper into the forest, until at last they come upon a beautiful clearing that possessed both "an air of antique wisdom" and "tranquil friendliness." "Was I not right?" Olivier queried. "Is there ought to fear in harmless trees and flowers?"

I doubt it will come as a surprise to anyone that Adele's fears are well grounded. Even as "the spell of their desire" is upon them and "everything beyond their own bodies, their own hearts" is "vaguer than a dream," they nevertheless become aware that they are being watched.

The apparition was incredible; and, for the space of a long breath, they could not believe they had really seen it. There were two horns in a matted mass of coarse, animal-like hair above the semi-human face with its obliquely slitted eyes and fang-revealing mouth and beard of wild-boar bristles. The face was old - incomputably old; and its lines and wrinkles were those of unreckoned years of lust; and its look was filled with the slow, unceasing increment of all the malignity and corruption and cruelty of elder ages. It was the face of Pan, as he glared from his, secret wood upon travellers taken unaware.

In both versions of the story, the leering vision serves as a catalyst for Adele to fling herself into the arms of Olivier and, at long last, they give into the unspoken ardor that they had long felt for one another. Later, their passion consummated, they lie together in the clearing, at which point Raoul finds them. In the published 1931 version, the Count prepares to impale both lovers with a thrust of his blade, but is prevented from doing so by the sudden appearance of the titular satyr, who grabs Adele and carries her off while laughing maniacally. In Smith's original version, Raoul succeeds in slaying the adulterers as he had planned. The satyr never appears in the flesh; instead, the count only hears his laughter.

Both endings have their merits. For myself, I prefer Smith's version, as there is some ambiguity as to whether or not the satyr exists at all or whether it might instead be a manifestation of Raoul's own bloodlust. In any case, "The Satyr," though a lesser work within the Smithian oeuvre, is a quite effective tale of horror and passion – fitting perhaps, given its title.

January 6, 2023

January 5, 2023

An Observation about Gygax's Modules

Between 1978 and 1985, TSR Hobbies published eighteen stand-alone adventure modules carrying the byline of Gary Gygax, starting with Steading of the Hill Giant Chief in 1978. Because it was the first of its kind, module G1 does not include a suggested level range on its cover. Instead, there is an interior section, labeled "CAUTION," that states the following:

Between 1978 and 1985, TSR Hobbies published eighteen stand-alone adventure modules carrying the byline of Gary Gygax, starting with Steading of the Hill Giant Chief in 1978. Because it was the first of its kind, module G1 does not include a suggested level range on its cover. Instead, there is an interior section, labeled "CAUTION," that states the following:Only strong characters should adventure into the Steading of the Hill Giant Chief if the party is but 3 or 4 strong. 6th or 7th level characters are suggested only when the party numbers 5 or more and only if most of the party is of higher level. The optimum mix for a group is 9 characters of various classes, with an average experience level of at least the 9th, and each should have 2 or 3 magic items.

The module's immediate sequels, The Glacial Rift of the Frost Giant Jarl and Hall of the Fire Giant King, include similar notes of caution that more or less reproduce what is stated above. When the three modules were collected together under one cover as Against the Giants in 1981, they were given a suggested level range of 8–12, which seems a bit higher than how I read Gygax's words.

Also published the same year was module D1, Descent into the Depths of the Earth, includes its own note of caution:

Those familiar with the previous modules in this scenario will be aware that they are designed for play only by players of above-average ability who have characters of high level – 9th or 10th minimum, counting multi-classed characters as roughly equal to a single classed character two levels higher than the character's higher level (three levels if triple classed) ... The module is designed for characters of about 10th level, with a party size of 7 to 9.

Module D2,

Shrine of the Kuo-Toa

, offers similar advice, as does module D3, Vault of the Drow. Later reprintings of these modules (again, in 1981) would combine D1 and D2 and peg its level range at 9–14 and D3 at 10–14. (The conclusion to the Giants-Drow series, 1980's

Queen of the Demonweb Pits

, is largely by David C. Sutherland III but Gygax is given a "with" credit, since it's at least partially based on his ideas. In any event, it too is listed as being appropriate for character levels 10–14.)

Module D2,

Shrine of the Kuo-Toa

, offers similar advice, as does module D3, Vault of the Drow. Later reprintings of these modules (again, in 1981) would combine D1 and D2 and peg its level range at 9–14 and D3 at 10–14. (The conclusion to the Giants-Drow series, 1980's

Queen of the Demonweb Pits

, is largely by David C. Sutherland III but Gygax is given a "with" credit, since it's at least partially based on his ideas. In any event, it too is listed as being appropriate for character levels 10–14.)I find it interesting, as others undoubtedly have, that the first six modules TSR released for use with AD&D were all aimed at fairly high-level characters – roughly the 8–12 range. The seventh module released in 1978, Tomb of Horrors, doesn't include the same note of caution regarding levels. Instead, only that it is "A THINKING PERSON'S MODULE" with few monsters and whose challenges are meant to be" solved by brains and not brawn." That said, Tomb of Horrors does include a roster of pregenerated characters that range in level from 6 to 14. The later 1981 reprinting opts instead for a 10–14 range.

In 1979, TSR publishes The Village of Hommlet. Again, it has no level range listed on its cover, but "Notes for the Dungeon Master" explains that "this module is designed for beginning play" and that experienced players "should start new, 1st level characters." The cover of the 1981 reprint – a recurring theme! – states that it is for "Introductory to Novice Level." Later in 1979, Gygax's name would also appear on The Keep on the Borderlands. This is the first of his modules to specify a level range on its original cover, in this case 1–3.

There's then a gap of three years before Gygax's name again graces the cover of a D&D module of any kind. That's when The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun is published, with a stated level range of 5–10. The next year, 1983, we see Dungeonland and its sequel,

The Land Beyond the Magic Mirror

, both of which are suggested for levels 9–12. 1984's Mordenkainen's Fantastic Adventure is for the same level range, while 1985's

Isle of the Ape

, Gygax's last published adventure module for TSR, is for levels 18+.

There's then a gap of three years before Gygax's name again graces the cover of a D&D module of any kind. That's when The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun is published, with a stated level range of 5–10. The next year, 1983, we see Dungeonland and its sequel,

The Land Beyond the Magic Mirror

, both of which are suggested for levels 9–12. 1984's Mordenkainen's Fantastic Adventure is for the same level range, while 1985's

Isle of the Ape

, Gygax's last published adventure module for TSR, is for levels 18+.Looking at the totality of his published output, as I've just done, it would seem that, by and large, Gygax wasn't all that interested in low-level adventures – or at least he wasn't interested in writing them. This might be because he simply found higher-level scenarios more compelling or because he felt there was a greater need for published examples of what higher-level play could be. Either way, he devoted himself to writing a significant number of modules in the 9th–12th level range, with only a small number of outliers.

Personally, I find this quite fascinating, if only because it runs counter to the conventional wisdom that Dungeons & Dragons, as a game line and as a product, benefits most from having lots of support for low to mid-level play. If you look at TSR's output over the years of its existence, you'll see lots of adventures in the levels 4–7 range and comparatively fewer at higher levels (though, again, there are outliers here and there). I know that my own personal preference has always been toward a similar middle span of levels and have often felt that every edition of D&D starts to creak after about level 9 or so, though Gygax would seem to have felt differently. If so, it makes me wonder all the more what his version of Second Edition might have looked like.

EDIT: I inexplicably left out both Expedition to the Barrier Peaks (8–12) and The Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth (6–10), two modules I like a great deal.

January 4, 2023

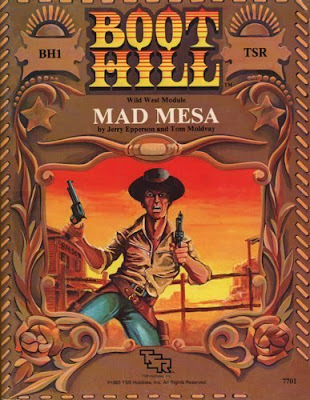

Retrospective: Mad Mesa

Every now and then, as I consider the subject of the next entry in this series, I come across one whose primary interest is not its content so much as its form. That's the case with Mad Mesa, the very first module produced by TSR in 1981 for use with Boot Hill. This fact alone makes it notable. While the module format was originally created for use with Dungeons & Dragons, TSR would eventually publish modules for all of their roleplaying lines, though most were never as extensive (or successful) as those for D&D. Boot Hill would eventually have only five modules, the lowest number, I believe, of any TSR RPG. This small number gives each published entry added weight when looking at it.

Every now and then, as I consider the subject of the next entry in this series, I come across one whose primary interest is not its content so much as its form. That's the case with Mad Mesa, the very first module produced by TSR in 1981 for use with Boot Hill. This fact alone makes it notable. While the module format was originally created for use with Dungeons & Dragons, TSR would eventually publish modules for all of their roleplaying lines, though most were never as extensive (or successful) as those for D&D. Boot Hill would eventually have only five modules, the lowest number, I believe, of any TSR RPG. This small number gives each published entry added weight when looking at it.Consider, too, the module's byline: "by Jerry Epperson and Tom Moldvay." Tom Moldvay is a name that needs no introduction to anyone reading this blog, but Jerry Epperson? Who is he? That's a good question and I wish I could provide a good answer. He seems to have been a freelance writer rather than an employee of TSR, like Moldvay. He'd later go on to contribute to a handful RPG products over the years (for GURPS, Marvel Super Heroes, and Shadowrun), but doesn't appear to have otherwise left a significant mark on the hobby. Epperson dedicates Mad Mesa to, among other people, Moldvay, "who took an idea and breathed into it the essence of life." This suggests to me that Moldvay had a much bigger hand in the final product than his secondary credit in the byline might imply.

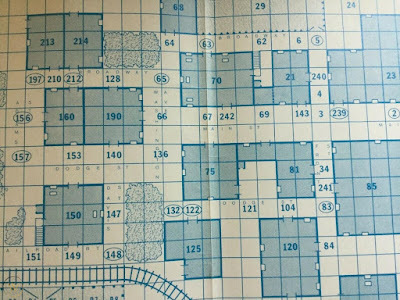

Like most modules of the time, Mad Mesa is 32 pages long and is divided into two uneven sections, along with a map on its interior cover. Here's what part of the map looks like, because it's quite unusual:

As you can see, there are numbered buildings, as one might expect on map of this kind. However, there are also numbers located elsewhere, such as on the streets of the titular town of Mad Mesa. Some of these numbers are circled. The numbers are all used not merely as part of a traditional map key but as entries in a solitaire adventure scenario that makes up the bulk of the module. Whenever the solo player's character enters an area with a number, he consults the appropriate entry in the book to see what he encounters. Entries with circles around them indicate "chance encounters," which is to say, a random encounter, the results of which are determined by consulting tables also in the book.

As you can see, there are numbered buildings, as one might expect on map of this kind. However, there are also numbers located elsewhere, such as on the streets of the titular town of Mad Mesa. Some of these numbers are circled. The numbers are all used not merely as part of a traditional map key but as entries in a solitaire adventure scenario that makes up the bulk of the module. Whenever the solo player's character enters an area with a number, he consults the appropriate entry in the book to see what he encounters. Entries with circles around them indicate "chance encounters," which is to say, a random encounter, the results of which are determined by consulting tables also in the book.I find it fascinating that the very first Boot Hill module contains a lengthy solitaire scenario, which takes up 24 of its 32 pages. It's doubly fascinating when you consider that the second part of the module contains a multi-player adventure that depends on the referee's having already played through the solo scenario "so that he or she can use the information to smoothly run the multi-player adventure." Indeed, the multi-player adventure is little more than a more freeform and elaborated version of the solo adventure, which involves the characters having come to the frontier settlement of Mad Mesa just as the long-simmering feud between the Russells and the Kanes – two ranching factions – boils over into violence.

As presented, both versions of the module's scenario are fairly open-ended and I dare say "Braunstein-like." The characters are caught up in the machinations of larger factions with their own agendas and it's up to the player(s) to navigate this as best they are able, even to the point of playing one faction off against another, Clint Eastwood-style. Of all of TSR's published roleplaying games, Boot Hill seems to have stayed closest to its original miniature wargaming roots and that comes across very clearly in Mad Mesa. Younger gamers or those simply unfamiliar with the history of the hobby might well find this aspect of the module strange, even off-putting, but I find it a useful reminder of where it all began.

Finally, Mad Mesa is worthy of note for one other reason: its artwork. TSR in 1981 had a remarkable and varied bullpen of illustrators and this module makes use of almost all of them. There are thus pieces by Jeff Dee, David "Diesel" LaForce, Jim Roslof, Bill Willingham, and even Erol Otus. It's an incredible lineup, all the more so because they're illustrating a western adventure rather than a fantasy or science fiction one. It's a pity that most of them wouldn't be employed by TSR much beyond the publication date of Mad Mesa, but, during the time they were there, they certainly left an impression.

January 3, 2023

Cartographer and Linguist

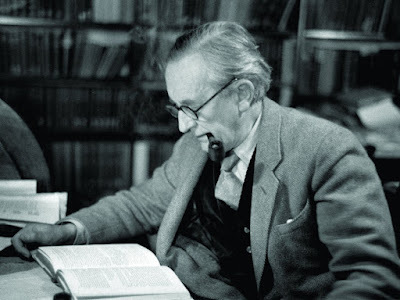

Over the years, this blog has been host to numerous discussions regarding the extent to which the works of J.R.R. Tolkien have influenced the creation and subsequent development of Dungeons & Dragons. Rather than rehearsing those arguments yet again, I thought it might be more profitable to commemorate Tolkien's 131st birthday by looking at a couple of ways that he indisputably changed the form and presentation of fantasy stories.

Over the years, this blog has been host to numerous discussions regarding the extent to which the works of J.R.R. Tolkien have influenced the creation and subsequent development of Dungeons & Dragons. Rather than rehearsing those arguments yet again, I thought it might be more profitable to commemorate Tolkien's 131st birthday by looking at a couple of ways that he indisputably changed the form and presentation of fantasy stories. By profession, Tolkien was a philologist, which is to say, a scholar of the history of languages and their associated bodies of literature. In his case, Tolkien specialized in Old and Middle English, as well as taking a scholarly interest in other tongues that had had an influence on them, such as Old Norse. His interest in these matters grew out of his youthful enthusiasm for languages, an enthusiasm that led him to try his hand at the construction of imaginary ones – glossopoeia, as he would later coin it – during his adolescence. He would later famously devote himself more fully to this avocation, creating the Elvish language of Quenya, along with portions of a few others spoken by the various peoples of Middle-earth.

In many ways, this is one of the distinguishing features of Middle-earth. Indeed, it could plausibly be said that the stories of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion, and Tolkien's other unfinished works were all, to varying degrees, an outgrowth of his interest in the philology of his constructed languages. His approach to writing fiction could thus be described as "from the ground up." since he placed a great deal of importance on the plausibility and verisimilitude of his "sub-creation." Tolkien meant Middle-earth to be a real place inhabited by real peoples with their histories, cultures, and languages. Anything less would have been, in his eyes, a failure.

While I am hard pressed to think any significant post-Tolkien fantasy author who has put as much effort into developing constructed languages as he did, I think it's nevertheless quite fair to say that most of those who followed in his wake at least take a stab at his ideal of sub-creation. This isn't to suggest that every phonebook-sized fantasy novel that's come out since the 1970s possesses the depth and breadth of Middle-earth, only that I think, with very few exceptions, most fantasy writers look upon the depth and breadth of Middle-earth as ideals to be emulated, even if they fall short of it.

One place where this can be seen most clearly, I think, is in the importance placed on having a map of one's setting. Tolkien was not the first author to do this, of course, but I don't think it's a stretch to say that the maps included in every edition of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings – the latter especially – have had a profound influence on innumerable fantasy authors. Like Tolkien's languages, they helped lend reality to his fantasy world, to (literally) ground it in geography and a sense of place that was often lacking in earlier fantasies. Crack open almost any fantasy novel written nowadays and I'd wager that there's a very good chance you'll find a map of its setting somewhere. That speaks, in my opinion, to the impressive hold that Tolkien has over how we think of fantasy, even decades after his death.

The English philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead once wrote, "The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato." I would contend that, in most respects, the same is true with regards to Tolkien and the mass market fantasy genre. Even writers like Michael Moorcock, who loudly say silly things about Tolkien and reject his legacy, are nevertheless acknowledging the immensity of that legacy. Otherwise, there'd be no need to denounce and belittle him, would there? Like Plato, J.R.R. Tolkien simply cannot be ignored by anyone who wishes to write literary fantasy, which is why I continue to mark his birthday each year.

January 2, 2023

The Tumíssan Underworld

While I am busy developing the Vaults of da-Imer as my Dungeon23 project, cartographer extraordinaire, Dyson Logos, has decided to devote himself to the underworld beneath the western Tsolyáni city of Tumíssa.

Dyson plays the stolid warrior Grujúng hi Znáyu in my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. Over the last nearly eight (!) years of play, he's established himself as not just one of the pillars of the campaign but also as a keen student of all things Tékumel. That's why I'm really looking forward to seeing what he comes up with as he works his way through this project. By the end of the year, his Tumíssan Underworld will likely have become one of the most extensive "dungeons" ever made for use in Tékumel. I have no doubt it'll be a great one.

Dyson plays the stolid warrior Grujúng hi Znáyu in my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. Over the last nearly eight (!) years of play, he's established himself as not just one of the pillars of the campaign but also as a keen student of all things Tékumel. That's why I'm really looking forward to seeing what he comes up with as he works his way through this project. By the end of the year, his Tumíssan Underworld will likely have become one of the most extensive "dungeons" ever made for use in Tékumel. I have no doubt it'll be a great one.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers