Cartographer and Linguist

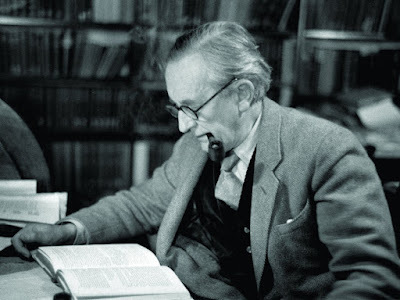

Over the years, this blog has been host to numerous discussions regarding the extent to which the works of J.R.R. Tolkien have influenced the creation and subsequent development of Dungeons & Dragons. Rather than rehearsing those arguments yet again, I thought it might be more profitable to commemorate Tolkien's 131st birthday by looking at a couple of ways that he indisputably changed the form and presentation of fantasy stories.

Over the years, this blog has been host to numerous discussions regarding the extent to which the works of J.R.R. Tolkien have influenced the creation and subsequent development of Dungeons & Dragons. Rather than rehearsing those arguments yet again, I thought it might be more profitable to commemorate Tolkien's 131st birthday by looking at a couple of ways that he indisputably changed the form and presentation of fantasy stories. By profession, Tolkien was a philologist, which is to say, a scholar of the history of languages and their associated bodies of literature. In his case, Tolkien specialized in Old and Middle English, as well as taking a scholarly interest in other tongues that had had an influence on them, such as Old Norse. His interest in these matters grew out of his youthful enthusiasm for languages, an enthusiasm that led him to try his hand at the construction of imaginary ones – glossopoeia, as he would later coin it – during his adolescence. He would later famously devote himself more fully to this avocation, creating the Elvish language of Quenya, along with portions of a few others spoken by the various peoples of Middle-earth.

In many ways, this is one of the distinguishing features of Middle-earth. Indeed, it could plausibly be said that the stories of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion, and Tolkien's other unfinished works were all, to varying degrees, an outgrowth of his interest in the philology of his constructed languages. His approach to writing fiction could thus be described as "from the ground up." since he placed a great deal of importance on the plausibility and verisimilitude of his "sub-creation." Tolkien meant Middle-earth to be a real place inhabited by real peoples with their histories, cultures, and languages. Anything less would have been, in his eyes, a failure.

While I am hard pressed to think any significant post-Tolkien fantasy author who has put as much effort into developing constructed languages as he did, I think it's nevertheless quite fair to say that most of those who followed in his wake at least take a stab at his ideal of sub-creation. This isn't to suggest that every phonebook-sized fantasy novel that's come out since the 1970s possesses the depth and breadth of Middle-earth, only that I think, with very few exceptions, most fantasy writers look upon the depth and breadth of Middle-earth as ideals to be emulated, even if they fall short of it.

One place where this can be seen most clearly, I think, is in the importance placed on having a map of one's setting. Tolkien was not the first author to do this, of course, but I don't think it's a stretch to say that the maps included in every edition of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings – the latter especially – have had a profound influence on innumerable fantasy authors. Like Tolkien's languages, they helped lend reality to his fantasy world, to (literally) ground it in geography and a sense of place that was often lacking in earlier fantasies. Crack open almost any fantasy novel written nowadays and I'd wager that there's a very good chance you'll find a map of its setting somewhere. That speaks, in my opinion, to the impressive hold that Tolkien has over how we think of fantasy, even decades after his death.

The English philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead once wrote, "The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato." I would contend that, in most respects, the same is true with regards to Tolkien and the mass market fantasy genre. Even writers like Michael Moorcock, who loudly say silly things about Tolkien and reject his legacy, are nevertheless acknowledging the immensity of that legacy. Otherwise, there'd be no need to denounce and belittle him, would there? Like Plato, J.R.R. Tolkien simply cannot be ignored by anyone who wishes to write literary fantasy, which is why I continue to mark his birthday each year.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers