James Maliszewski's Blog, page 84

February 9, 2023

Patient Zero

With the publication of the Dungeon Masters Guide in August 1979, Gary Gygax's Advanced Dungeons & Dragons project was essentially complete (though we would nevertheless see the publication of not one but two more hardback AD&D volumes over the next couple of years). Consequently, 1980 was the start of a period in TSR's history when the company shifted its focus to supporting Dungeons & Dragons in both its Basic and Advanced formats. One of the most significant ways it did so was through the publication of numerous adventure modules. Indeed, by dint of the sheer number of them released, adventure modules would effectively become TSR's signature products.

With the publication of the Dungeon Masters Guide in August 1979, Gary Gygax's Advanced Dungeons & Dragons project was essentially complete (though we would nevertheless see the publication of not one but two more hardback AD&D volumes over the next couple of years). Consequently, 1980 was the start of a period in TSR's history when the company shifted its focus to supporting Dungeons & Dragons in both its Basic and Advanced formats. One of the most significant ways it did so was through the publication of numerous adventure modules. Indeed, by dint of the sheer number of them released, adventure modules would effectively become TSR's signature products.Among the modules published in 1980 was Harold Johnson and Jeff R. Leason's The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan . Designated module C1 (for "Competition"), the module is highly regarded for both its exotic Mesoamerican-inspired flavor and the cleverness of its many tricks and traps. Johnson and Leason originally wrote the module for use at the Official Advanced Dungeons & Dragons tournament at Origins '79, hence its "competition" designation. For that reason, it includes an extensive scoring system for tournament use, as well as a strict real time limit of 2 hours to complete.

In addition, the module includes the following in its "Notes for the Dungeon Master:"

It will be noticed that encounter descriptions are divided into boxed and open sections. The boxed sections contain information which should be read to the players; the rest is information for the DM. In most cases, the same players' description is used no matter which direction the party enters from, but 2 cases require that special descriptions be read depending on the direction from which the party approaches the encounter area. The DM should be aware of this and be careful to read the proper players' description.

The players' descriptions are provided because many of the encounters require specific actions on the part of the group. Hints of what may be done are given in this text and the DM should only provide vague information if questioned. Plauers will be to see the exact contents of a room unless noted.

Unless I am mistaken – and please correct me if I am – this is the very first published appearance of the dreaded boxed text in any TSR module.

Within the very specific context of a module written for tournament use, particularly one with a strict real time limit, the inclusion of boxed, descriptive text makes a great deal of sense. After all, it would be unfair to the players participating in the tournament if some referees were more loquacious than others in their descriptions, time being a valuable resource. Fairness would likewise demand that each group of players be given the exact same descriptions of the dungeon's rooms. Once again, I say this makes perfect sense within this very specific context.

The trouble, I think, arises when TSR, in an effort to publish a large number of modules over a short period of time, turned ever more often to those originally created for tournaments. In this way, the style and presentation of tournament modules, including read-aloud boxed text, came to be seen not as unique features of tournament modules as such but simply as features of D&D modules in general. This is especially notable in modules published for the Basic and Expert versions of D&D, but, over time, it comes to be standard even in AD&D modules.

The lasting impact of the D&D tournament scene cannot be overstated.

Thoroughly

From Dungeons & Dragons module B2, Keep on the Borderlands:

The use of this module requires a working familiarity with its layout and design. Therefore, the first step is to completely read through the module, referring to the maps provided to learn the locations of the various features. A second (and third!) reading will be helpful in learning the nature of the monsters, their methods of attack and defense, and the treasures provided.

From module B3, Palace of the Silver Princess:

Before beginning the adventure, the DM should read this module thoroughly to become familiar with its details.

From module B4, The Lost City:

Before beginning the adventure, please read the module thoroughly to become familiar with the Lost City.

From Advanced Dungeons & Dragons module A1, Slave Pits of the Undercity:

Before commencing play, it is recommended that the DM read the module thoroughly and become familiar with the information given.

From module A2, Secret of the Slavers Stockade:

Before beginning play, the DM must read all parts of the module thoroughly.

From module C1, The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan:

It is recommended that the DM read the module thoroughly several times before play starts, making notes in the margins where useful.

From module C2, The Ghost Tower of Inverness:

It is necessary that the DM read the module thoroughly before play. It may be useful to make notes in the margins at some points.

From module S1, Tomb of Horrors:

Please read and review all of the material herein, and become thoroughly familiar with it before beginning the module.

From module S2, White Plume Mountain:

Please read the entire module through and thoroughly familiarize yourself with complex areas before beginning play.

From module S3, Expedition to the Barrier Peaks:

Be certain that you are quite familiar with the entire module, and read each encounter section carefully.

etc. etc.

February 8, 2023

Retrospective: Steading of the Hill Giant Chief

I was recently re-reading Steading of the Hill Giant Chief, largely due to its distinction as the first adventure module published by TSR for use with any version of Dungeons & Dragons. My intention was to see what, if anything, the module had to say about itself and how it was intended to be used by the referee. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given its relatively early publication date (1978), module G1 doesn't say much on these topics, but what it does say is, I think, of interest and thus worthy of this post.

I was recently re-reading Steading of the Hill Giant Chief, largely due to its distinction as the first adventure module published by TSR for use with any version of Dungeons & Dragons. My intention was to see what, if anything, the module had to say about itself and how it was intended to be used by the referee. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given its relatively early publication date (1978), module G1 doesn't say much on these topics, but what it does say is, I think, of interest and thus worthy of this post.

I long ago wrote a Retrospective on the 1981 compilation of all three G-series modules, Against the Giants. That post was narrow in its focus, containing little analysis of any of the constituent modules. Instead, it presented my recollections of having played and refereed the modules over the years. The present post is similarly narrow, focusing on the prefatory material at the beginning of Steading of the Hill Giant Chief, where Gary Gygax speaks directly to the referee.

The "Notes for the Dungeon Master" begin thusly:

There is considerable information contained herein which is descriptive and informative with respect to what the players see and do. Note that this does not mean that you, as Dungeon Master, must surrender your creativity and become a mere script reader.

TSR reputedly hadn't published a stand-alone adventure for D&D prior to this point precisely because it did not believe there would be a market for such things. There was a belief that, echoing the sentiments of OD&D's afterword, referees would not want TSR to do any more of their imagining for them. The success of Palace of the Vampire Queen and the early Judges Guild materials demonstrated the falsity of this belief and so TSR decided to enter the adventure-publishing business, releasing more than a half-dozen modules in 1978 alone. Bearing all that in mind, this reassurance that the referee is no "mere script reader" perhaps suggests that there was some concern – real or imagined – that referees might come to view their role in this way.

You must supply considerable amounts of additional material. You will have to make up certain details of area. There will be actions which are not allowed for here, and you will have to judge whether or not you will permit them.

To my mind, this section suggests that Gygax viewed an adventure module as an outline and a foundation on which to build rather than as a complete, ready-to-use product that did all the referee's work for him. Given that this was the general attitude at the time even toward the rules of roleplaying games, I think this view was a sensible one. Nevertheless, the fact that Gygax felt it necessary to state this explicitly makes me wonder about how the hobby might already have been changing a mere four years after its formal start.

Finally, you can amend and alter monsters and treasures as you see fit, hopefully within the parameters of this module, and with an eye towards the whole, but to suit your particular players.

Here, Gygax is simultaneously reminding the referee that his is the final decision in all matters, even when using a published module, and that any such decision should take into account the facts as the module presents them. Consistency and continuity are, therefore, important considerations, which is a point he emphasizes later in this same section.

The "Notes for the Dungeon Master" point out that the giants are "clever" and will "organize traps, ambushes, and last-ditch defenses against continuing forays into their stronghold." Note the use of the adjective "continuing." Gygax assumes that no party will be able to "clear" the Steading in a single assault, which is why he references the existence of a "hidden cave base camp" to which the characters can return to rest, heal, and even "receive experience point benefits." What Gygax clearly envisages is not a "one and done" attack against the giants but a series of regular, military-style forays between which the surviving giants will take precautions against the characters.

On the matter of continuity, Gygax explains:

If you plan to continue this campaign by using the other modules in the series, be certain to keep track of the fate of important giants and their allies or captives. The former will generally flee to the next higher ranking stronghold, and the latter will be available for assistance to some parties. This assumes survival, of course, as well as opportunity.

The usage of "campaign" in this fashion reinforces the military nature of the characters' assault, I think. He goes on with more advice about handling continuity:

Some provisions for movement of surviving giants is shown in MODULES G2, G3, et al., but you will have to modify or augment these groups according to the outcome of previous adventuring by your party. This principle will also hold true with regard to any additional scenarios which you use if they concern any of the creatures connected with this series. Such continuity of encounters will certainly tend to make the adventures of the party more meaningful and exciting.

This is all very much in keeping with the Gygaxian principles laid out again and again in the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide. Gygax was much concerned with the construction and presentation of a consistent, persistent setting so that players could make rational decisions about their characters' actions. Indeed, I'd go so far as to say this was the hallmark of his conception not just of Dungeons & Dragons but of roleplaying more generally. Anything less rigorous than that he would have, I imagine, viewed as fundamentally unfair and against the spirit of the entire enterprise of roleplaying.

Because of its place as the first module published by TSR, Steading of the Hill Giant Chief is fairly unambitious in both its content – the whole thing is only 8 pages long – and in its presentation. Despite its brevity, one can already detect within it the beginnings of a philosophy of not just adventure design but of play that I think is well worth further examination, as are all the Gygax-penned modules of 1978.

February 6, 2023

Hex Help

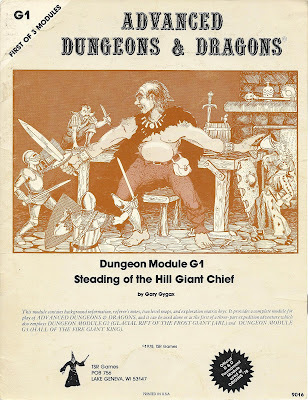

Much as I adore the incomparable map of the Flanaess from the World of Greyhawk – perhaps the best RPG map ever – over the last few years I've really come to appreciate the style of hex map that appeared during the Moldvay/Cook/Marsh era of Dungeons & Dragons. Though nowhere as artful in their presentation as Darlene's gorgeous work, the B/X hex maps do nevertheless have a beauty all their own, one born of clarity and utility. They are very easy to read and to use in play, especially if, like me, you are saddled with eyesight that's nowhere near as sharp as it once was. This fact alone counts for a great deal nowadays.

Much as I adore the incomparable map of the Flanaess from the World of Greyhawk – perhaps the best RPG map ever – over the last few years I've really come to appreciate the style of hex map that appeared during the Moldvay/Cook/Marsh era of Dungeons & Dragons. Though nowhere as artful in their presentation as Darlene's gorgeous work, the B/X hex maps do nevertheless have a beauty all their own, one born of clarity and utility. They are very easy to read and to use in play, especially if, like me, you are saddled with eyesight that's nowhere near as sharp as it once was. This fact alone counts for a great deal nowadays.That's why I'd like to prevail upon the collective knowledge of my readers. Are there any programs out there that might enable an incompetent Luddite such as myself to make rough approximations of these maps? Once upon a time, there was a program called Hexographer that came close to doing so, but its current iteration looks much too complex for some of my limited skills to use effectively. Are there any alternatives readily available or must I buckle under and learn how to use this new version of Hexographer?

February 5, 2023

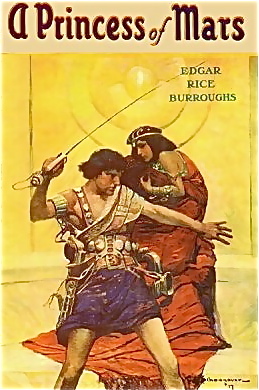

Pulp Fantasy Gallery: A Princess of Mars

Since the real world continues to be demanding of late – my apologies for the lighter than normal posting – I've decided to present another entry in the Pulp Fantasy Gallery series. This week, I've opted to go back more than a century, to one of the foundational works of fantasy and science fiction (not to mention roleplaying games), Edgar Rice Burroughs's A Princess of Mars. Long-time readers may recall that I had previously included this book in an early installment of Pulp Fantasy Gallery. In that post, I only highlighted an image of perhaps the most famous – and, in my opinion, best – cover illustration, that by Frank E. Schoonover.

I'm apparently not alone in my appreciation for this cover, because it was used again and again throughout the ensuing decades. Indeed, it seems to have been the only cover illustration for US editions of A Princess of Mars until the early 1960s, nearly a half-century after its initial appearance. The first new cover illustration of which I am aware is this one by Roy Carnon, from the 1961 Four Square Books paperback edition:

I'm apparently not alone in my appreciation for this cover, because it was used again and again throughout the ensuing decades. Indeed, it seems to have been the only cover illustration for US editions of A Princess of Mars until the early 1960s, nearly a half-century after its initial appearance. The first new cover illustration of which I am aware is this one by Roy Carnon, from the 1961 Four Square Books paperback edition:

A couple of years later, in January 1963, Ballantine releases this version, with a cover by Bob Abbett. I find it especially interesting, because it looks as if it takes many of its cues from the original Schoonover cover, albeit with the color schemes of John Carter and Dejah Thoris reversed.

A couple of years later, in January 1963, Ballantine releases this version, with a cover by Bob Abbett. I find it especially interesting, because it looks as if it takes many of its cues from the original Schoonover cover, albeit with the color schemes of John Carter and Dejah Thoris reversed.

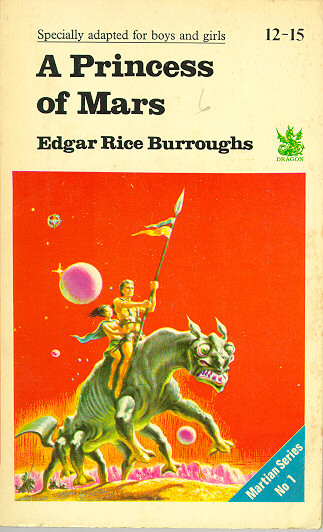

In 1968, there's an abridged version of A Princess of Mars from Dragon, a publisher who specialized in children's versions of "classic" stories. The cover artist would seem to be unknown.

In 1968, there's an abridged version of A Princess of Mars from Dragon, a publisher who specialized in children's versions of "classic" stories. The cover artist would seem to be unknown.

Bruce Pennington provides the very striking cover for the 1969 New English Library edition, which is the first not to depict John Carter.

Bruce Pennington provides the very striking cover for the 1969 New English Library edition, which is the first not to depict John Carter.

The 1970 Nelson Doubleday/Science Fiction Book Club edition is understandably famous for its use of Frank Frazetta's iconic cover, my second favorite after Schoonover's original.

The 1970 Nelson Doubleday/Science Fiction Book Club edition is understandably famous for its use of Frank Frazetta's iconic cover, my second favorite after Schoonover's original.

When Ballantine issued a new edition in 1973, it featured this cover by Gino D'Achille:

When Ballantine issued a new edition in 1973, it featured this cover by Gino D'Achille:

Finally, in 1979, we get the Del Rey edition with Michael Whelan's cover. Because this is the first edition of the novel I ever owned, I retain a certain fondness for it. Apparently, publishers feel similarly, because, like the Schoonover cover before, it's been used again and again since its initial appearance, with editions as recent as just a few years ago still making use of it.

Finally, in 1979, we get the Del Rey edition with Michael Whelan's cover. Because this is the first edition of the novel I ever owned, I retain a certain fondness for it. Apparently, publishers feel similarly, because, like the Schoonover cover before, it's been used again and again since its initial appearance, with editions as recent as just a few years ago still making use of it.

February 3, 2023

Labyrinth Repair Shop

Long ago – more than a decade now, if you can believe it – I wrote a Retrospective post in which I talked about the Dungeons & Dragons Computer Labyrinth Game released by Mattel Electronics in 1980. Though I never owned the game myself, a close friend of mine did and I took advantage of this fact to play it as often as I could. Though I'm not certain that I could unambiguously call it a "good" game, I nevertheless retain a weird affection for it, as I do for many other examples of transitional technology from my long-ago youth.

Long ago – more than a decade now, if you can believe it – I wrote a Retrospective post in which I talked about the Dungeons & Dragons Computer Labyrinth Game released by Mattel Electronics in 1980. Though I never owned the game myself, a close friend of mine did and I took advantage of this fact to play it as often as I could. Though I'm not certain that I could unambiguously call it a "good" game, I nevertheless retain a weird affection for it, as I do for many other examples of transitional technology from my long-ago youth.Rob Conley alerted me to the existence of a blog post over at Old Vintage Computer Research, in which the author pulls out his copy of the game (which he barely played at the time he first received it), examines it in detail, and then sets about repairing it so that he can finally get around to playing it after all these years. It's a terrific post, filled with lots of information on the inner working of the game. I suspect it'll be of great interest to anyone who, like myself, has a fondness for the electronic "boardgames" of the late '70s and early '80s.

(As an aside, it's worth noting that this game, as well as the slightly later Dungeons & Dragons Computer Fantasy Game, are D&D-branded rather than AD&D-branded, like the Intellivision game cartridges that appeared in 1982. I assume this is the result of various legal and financial wranglings at TSR vis à vis Dave Arneson, but have no proof of this one way or the other. Regardless, it's yet another fascinating wrinkle in the long history of attempts to turn Dungeons & Dragons into a mass market consumer brand.)

February 1, 2023

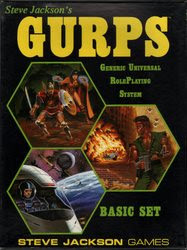

Retrospective: GURPS

Though I've never been a devoted user of universal roleplaying game systems, I've long been intrigued by the idea of them. My first brush with the concept was probably

Basic Role-Playing

, which I encountered through the first edition of Call of Cthulhu in 1981. Chaosium used BRP (derived from

RuneQuest

) as the foundation on which it would build the rulesets of its other roleplaying games, like Stormbringer. Ringworld, and the aforementioned Call of Cthulhu. Hero Games did something similar with the rules of Champions.

Though I've never been a devoted user of universal roleplaying game systems, I've long been intrigued by the idea of them. My first brush with the concept was probably

Basic Role-Playing

, which I encountered through the first edition of Call of Cthulhu in 1981. Chaosium used BRP (derived from

RuneQuest

) as the foundation on which it would build the rulesets of its other roleplaying games, like Stormbringer. Ringworld, and the aforementioned Call of Cthulhu. Hero Games did something similar with the rules of Champions.For me, the appeal of a universal system lay in the promise of never again having learn new rules just because I wanted to play a new game (or setting). As both a referee and a player, I'm indifferent to rules, except to the extent that I forget them or confuse them with the rules of another game with which I'm also familiar. In general, once I find a ruleset that works well enough for my purposes, I stick with it. This probably explains why I've played so much D&D and Traveller over the years, despite the existence of purportedly "better" systems for fantasy and science fiction: I know these rulesets and they're more than adequate for my purposes.

In my youth, I knew plenty of people who had adapted the rules of Dungeons & Dragons to their favorite genres or settings. This was, I gather, a common practice in the days when there were only a handful of different game systems. Even at the time, this felt odd to me, despite my affection for D&D and my facility with its rules. Nevertheless, I understood the impulse. Why reinvent the wheel? Why did every RPG have to have its own unique – and frequently idiosyncratic – game system? Wouldn't things be easier if you and your fellow players had to learn just one ruleset rather than a new one every time you started a campaign?

So, when I first heard about Steve Jackson's "Great Unnnamed Roleplaying System," I was more than a little intrigued. Though I had never played Jackson's previous RPG, The Fantasy Trip, I knew it was well regarded and, from what I had gathered, the then-upcoming GURPS was designed as a successor to and an expansion of the core concepts behind The Fantasy Trip. Plus, I was a very big fan of Jackson's Ogre and Cars Wars, both of which my friends and I played regularly. By my lights, this pretty much guaranteed that GURPS – or whatever its "real" name would eventually be – would be a winner.

The first publication to carry the GURPS name, Man to Man, was released in the summer of 1985, along with a collection of scenarios entitled Orcslayer. Man to Man was a kind of preview of GURPS, presenting the game's combat system. I never saw a copy of it at the time – indeed I've still never seen one – so its release came and went without much notice from me. By the time the full GURPS Basic Set was published the following year, in 1986, I had largely forgotten about the whole thing, so it too escaped my attention. I'm not entirely sure why this was, though I suspect, given the timing of its release, that I was distracted by other matters.

When I did finally see a copy of GURPS, it was already on its third edition. This would have been sometime in the late 1980s. The game was no longer sold as a boxed set with multiple booklets but as a single softcover volume. I ordered my copy through the mail, based on an advertisement I'd seen somewhere (Dragon? Challenge?), which reminded me that GURPS did indeed exist and that I'd once been quite interested in the project. I was very happy to receive it, along with a copy of the GURPS Space supplement, since I was then, as I am now, more or a sci-fi fan than a fantasy one.

I was very impressed with GURPS when I first read it. The rules were simple and easy to understand. The presentation was similarly straightforward – a no-nonsense layout with black and white art and informative little sidebars throughout. I loved how modular everything seemed, with skills, advantages, and disadvantages all capable of being added or swapped out, depending on the setting and genre of the campaign you were planning to run. Likewise, the supplementary material, like Space, provided lots of tailored options for the referee to consider. All in all, GURPS exceeded my expectations.

Unfortunately, I never got the chance to play much GURPS in the months immediately after I first bought it. It wasn't until several years later, after I'd graduated from university and moved to my present home, that I rectified this. My local friends had played GURPS extensively, having effectively abandoned all other game systems in its favor for several years beforehand. They thus knew the system's ins and outs and were quite happy to share their thoughts on the matter. By and large, their experiences were positive, but they also recognized that, at least in its third edition – things may have changed in more recent editions – the rules creaked somewhat the farther one got from the power and technological level of medieval fantasy. In short, GURPS had something of a scaling problem, particularly as one moved toward science fiction.

This was disappointing to hear, but it didn't stop me from making use of GURPS several times over the years. Whatever its flaws might be, it was still a simple and convenient way to play campaigns that deviated from those presented in other commercially available RPGs. It was a terrific "toolkit game" and its supplements were often among the most inspiring and best researched I'd ever seen. I continued to support the game for years, despite playing it only sporadically. That's no knock against the game itself so much as an acknowledgment that, despite my appreciation for it and what it tries to do, GURPS never succeeded in joining my list of go-to RPGs. I definitely think there's a place for a game like GURPS, which is much more accessible and user friendly than, say, HERO. That said, I'm much less convinced these days that a one-size-fits-all universal system is even possible, let alone desirable and so GURPS remains on my shelf, unplayed.

January 29, 2023

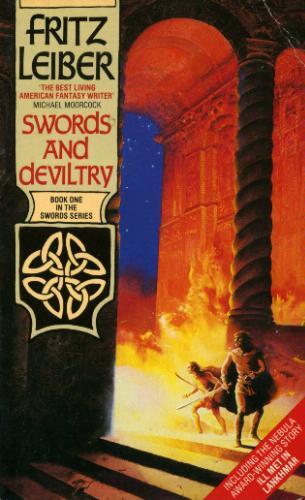

Pulp Fantasy Gallery: Swords and Deviltry

On some level that's a shame, because I continue to think the evolution of fantasy art is a fascinating subject, especially for those of us who favor the esthetics of earlier times. Because of this – and because I've found myself unexpectedly busy over the last week and thus unable to devote myself properly to Pulp Fantasy Library – I've decided to pen a new entry in Pulp Fantasy Gallery today. Whether I'll continue to do so on a regular basis, I don't know.

For now, let's take a look at five different cover illustrations created for the various English editions of Fritz Leiber's Swords and Deviltry. The first of these was published by Ace in May 1970 and featured artwork by Jeff Jones. Ace continued to use variations on this cover for more than fifteen years on its US editions of the book.

Not long thereafter, in December 1971, the New English Library released a UK edition of the book. The cover (by an unknown artist) bears a clear similarity to the Ace cover above.

Not long thereafter, in December 1971, the New English Library released a UK edition of the book. The cover (by an unknown artist) bears a clear similarity to the Ace cover above.

A second UK edition appeared in December 1977 from George Prior Publishers, with artwork by Wayne Barlow.

A second UK edition appeared in December 1977 from George Prior Publishers, with artwork by Wayne Barlow.

Just two years later, a third UK edition appeared from Mayflower, illustrated by Peter Elson.

Just two years later, a third UK edition appeared from Mayflower, illustrated by Peter Elson.

Continuing a theme, we have a fourth UK edition, this time from Grafton in July 1986, with Geoff Taylor doing the cover.

Continuing a theme, we have a fourth UK edition, this time from Grafton in July 1986, with Geoff Taylor doing the cover.

January 26, 2023

Nothing New Under the Sun

This week's installment of Pulp Fantasy Library discussed Robert E. Howard's story of Kull, "The Cat and the Skull." To the extent that the story is known at all, it's because it features the first appearance of the undead sorcerer. The revelation of his involvement in the events of the tale is quite memorable.

This week's installment of Pulp Fantasy Library discussed Robert E. Howard's story of Kull, "The Cat and the Skull." To the extent that the story is known at all, it's because it features the first appearance of the undead sorcerer. The revelation of his involvement in the events of the tale is quite memorable.

The face of the man was a bare white skull, in whose eye sockets flamed livid fire!

"Thulsa Doom!"

"Aye, I guessed as much!" exclaimed Ka-nu.

"Aye, Thulsa Doom, fools!" the voice echoed cavernously and hollowly. "The greatest of all wizards and your eternal foe, Kull of Atlantis! You have won this tilt but, beware, there shall be others."

Years ago, when I first read this story, I was convinced that it had to have been the origin of D&D's lich. While I knew the lich from the AD&D Monster Manual, with its unforgettable illustration by Dave Trampier, the lich was introduced into the game through Supplement I to OD&D, Greyhawk. There, liches are described as "skeletal monsters of magical original, each Lich being a very powerful Magic-User or Magic-User/Cleric in life, and now alive only by means of great spells and will." The longer description in the Monster Manual adds that a lich possesses not just a skeletal form but "eyesockets mere black holes with glowing points of light." That sound a lot like REH's description of Thulsa Doom to me.

Years ago, when I first read this story, I was convinced that it had to have been the origin of D&D's lich. While I knew the lich from the AD&D Monster Manual, with its unforgettable illustration by Dave Trampier, the lich was introduced into the game through Supplement I to OD&D, Greyhawk. There, liches are described as "skeletal monsters of magical original, each Lich being a very powerful Magic-User or Magic-User/Cleric in life, and now alive only by means of great spells and will." The longer description in the Monster Manual adds that a lich possesses not just a skeletal form but "eyesockets mere black holes with glowing points of light." That sound a lot like REH's description of Thulsa Doom to me.The early 1970s was a remarkable time for aficionados of Robert E. Howard's writing. Not only was Lancer releasing its paperback editions of Howard's sword-and-sorcery yarns, but Marvel Comics was producing comic adaptations of many of them as well. In addition to the much more well known and celebrated Conan the Barbarian (and, later, Savage Sword of Conan), Marvel adapted Howard's characters and stories in other

magazines, such as Monsters on the Prowl. Issue #16 of that magazine (April 1972) featured an original Kull story called "The Forbidden Swamp," in which Thulsa Doom is introduced to comics readers. As drawn by the brother and sister team of John and Marie Severin, Thulsa Doom shares a lot with D&D's lich, don't you think?

For years afterward, I held on to my theory that it was Thulsa Doom who had inspired Gary Gygax in his creation of the lich. Not only was there much similarity between their descriptions, but Thulsa Doom's earliest published appearance, whether in Lancer's King Kull anthology or Marvel's comics, occurred just before the publication of OD&D. There was thus a certain plausibility to the one having been inspired by the other.

As it turned out, my theory was wrong – or at least not the whole story. Many years later, in one of his many online question and answer threads, I recall that Gygax admitted he swiped the lich from "The Sword of the Sorcerer," a Kothar story by Gardner F. Fox. In that tale, Kothar encounters an undead sorcerer named Afgorkon, who is repeatedly referred to by the word "lich," something that cannot be said of Thulsa Doom so far as I can tell. That's not to say that Thulsa Doom might not have exercised some influence over the creation of D&D's lich, only that he wasn't, at least as far as Gygax claimed, the primary one. It's not as if the idea of a skeletal, undead sorcerer is a wholly unique idea anyway.

That's something I keep in mind whenever I look almost any element of Dungeons & Dragons. Very little of it is genuinely unique to the game. I'd wager that almost all of its monsters, spells, and magic items derive from a pre-existing story, comic, movie, or TV show. Indeed, it probably wouldn't take much work to demonstrate this, since Gygax and others were often quite open about the earlier creators and works that inspired them. I don't mean this to be a criticism – far from it! Rather, I bring this up simply as a reminder that what makes D&D special is not any of its individual elements, very few of which are original, but rather the strange alchemy of their admixture.

January 25, 2023

Retrospective: Blackmoor

Since last week's Retrospective was about Greyhawk, it seemed only right that this week's should be about Blackmoor. It's also appropriate because Supplement II to Original Dungeons & Dragons occupies a special place in the story of my explorations into the history of the hobby of roleplaying. When I was in high school, my father told me about a hobby shop near his workplace that was selling off all their "old D&D stuff" and he asked if were interested in any of it. I told him that, without a list of the titles they had on offer, there was no way I could answer. The next day, he went back to the store and brought me "samples" of what they had, among which was Blackmoor.

Since last week's Retrospective was about Greyhawk, it seemed only right that this week's should be about Blackmoor. It's also appropriate because Supplement II to Original Dungeons & Dragons occupies a special place in the story of my explorations into the history of the hobby of roleplaying. When I was in high school, my father told me about a hobby shop near his workplace that was selling off all their "old D&D stuff" and he asked if were interested in any of it. I told him that, without a list of the titles they had on offer, there was no way I could answer. The next day, he went back to the store and brought me "samples" of what they had, among which was Blackmoor.

At the time, I think I'd seen the occasional references to Blackmoor, such as in the preface to the Monster Manual. And, of course, I was familiar with the land of Blackmoor as it was briefly described in the World of Greyhawk. However, that was close to the extent of my knowledge, this being several years before the publication of the DA-series of D&D modules that began with Adventures in Blackmoor. Consequently, I was very excited to read this weird, little, brown book and see what secrets it might reveal.

I can't say for certain that Blackmoor revealed any secrets to me at that time, but I did find it a very peculiar book nonetheless. Gary Gygax's effusive foreword included references to Dave Arneson's Blackmoor campaign, as well as how he "would rather play in his campaign than any other." This certainly whetted my appetite for information about the campaign itself. Indeed, I was hoping that this little book might shed light on the mysterious northern land mentioned in the World of Greyhawk folio.

Instead what I found was a collection of disconnected rules, many of which looked like early versions of material I'd later see in various AD&D books. There were write-ups for the monk and assassin character classes, sages, diseases, and aquatic monsters – all stuff I'd seen previously in slightly different forms. The only rules in Blackmoor I hadn't seen before were the "Hit Location During Melee" sections. Though they intrigued me, I also found these rules somewhat out of place in Dungeons & Dragons, which conceived of hit points in a fairly abstract manner.

I was feeling a little confused and even let down by all of this. That's when I decided to look more closely at the sample adventure that took up almost twenty pages of Blackmoor. Entitled "The Temple of the Frog," it was quite different from any adventure I'd seen before. For one, its maps were clearly hand drawn, unlike the much more polished maps with which I was hitherto familiar from TSR's products. For another, its primary antagonist, the high priest of the Temple, Stephen the Rock, was described in great detail – including the fact that was "an intelligent humanoid from another world/dimension!" This really grabbed my attention, especially after it became clearer that Stephen possessed high-tech weapons and armor of a science fictional sort.

By this point, I'd already read Gygax's own Expedition to the Barrier Peaks, which also mixed the peanut butter of science fiction with the chocolate of fantasy, so the ideas presented in "The Temple of the Frog" weren't completely unfamiliar to me. At the same time, Arneson's adventure had a very distinct feel to it, one that differed considerably from Gygax's. The crashed alien spaceship in Barrier Peaks is basically a one-off dungeon, a weird locale separated from the wider world. The Temple of the Frog, though, is an active player in the world of Blackmoor; the Brothers of the Swamp are a rising power, whose ideology of batrachian supremacy over mankind might one day threaten the order of things. That their new high priest just so happens to be an alien possessed of advanced technology only makes the situation more potentially volatile.

When I first opened the pages of Blackmoor, I expected I'd probably find some new rules and ideas derived from Dave Arneson's Blackmoor campaign. Instead, what I got was a mishmash of ideas I'd mostly seen before and that, as I later learned, were largerly the work of other hands (Steve Marsh primarily). But then there was "The Temple of the Frog." Though it's almost completely lacking in larger details about the Blackmoor setting, its ideas and presentation took me by surprise. After reading the adventure, I wanted to know more about Arneson's odd setting and the way it might have mixed elements of science fiction and fantasy together.

That would have to wait a few more years, of course, but Blackmoor was the first step I took down that road. Prior to this, Dave Arneson himself was just a name I'd occasionally see in the credits of my D&D books and Blackmoor was just a mysterious land at the top of the World of Greyhawk map. Now, I knew a little better and for that reason I'll always be fond of OD&D's Supplement II.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers