James Maliszewski's Blog, page 80

March 31, 2023

Fear of Ruination

As my House of Worms campaign starts its ninth year, I've regularly found myself wondering, "How long can I keep this going?" House of Worms is, by a long shot, the longest continual campaign I've ever refereed and I'd like to keep it going for as long as possible. This campaign is regular source of satisfaction and joy for me and, I hope, for the players as well. These feelings are almost certainly why I so often worry that I'm on the verge of ruining it through poor judgment or some misstep on my part. I worry that, despite all evidence to the contrary, that the campaign isn't nearly as sturdy or resilient as it appears to be and that it could all come crashing down in an instant if I'm not careful.

As my House of Worms campaign starts its ninth year, I've regularly found myself wondering, "How long can I keep this going?" House of Worms is, by a long shot, the longest continual campaign I've ever refereed and I'd like to keep it going for as long as possible. This campaign is regular source of satisfaction and joy for me and, I hope, for the players as well. These feelings are almost certainly why I so often worry that I'm on the verge of ruining it through poor judgment or some misstep on my part. I worry that, despite all evidence to the contrary, that the campaign isn't nearly as sturdy or resilient as it appears to be and that it could all come crashing down in an instant if I'm not careful.To many of you reading this, that probably sounds irrationally anxious and you're probably correct in thinking this, but please allow me to explain where I am coming from. From its inception in March 2015, the House of Worms campaign has been very player-driven. After its initial kick-off, I rarely presented the players with "adventures," as they're usually understood. Instead, I strove to present a variety of situations and opportunities within the world of Tékumel that the players, through their characters, could either pursue or not, as they desired. Further, if the players wanted to pursue other opportunities, ones I'd not immediately considered, that was fine too. Truth be told, I prefer it when the players do most of the heavy lifting for the campaign, because I am by nature a lazy referee. Plus, it's been my experience that allowing the players to do their own thing is one of the keys to campaign longevity.

Over the past eight years, House of Worms has chugged along very smoothly, flitting from one situation to the next according to the interest of the players. Sometimes, the players have had clear and obvious goals, such as return home after a magical mishap hurled them far away, but most of their goals over the years have been much more open-ended and elusive. One of the advantages of this is that it's given me lots of opportunities to show different parts of Tékumel to them through play. I feel that's where a rich and detailed setting really pays off.

Though the players and their interests are the main drivers of the campaign, that doesn't mean I don't have ideas of my own, ideas that I'm interested in exploring through play. A good example of this concerns the nature of the gods of Tékumel, including their natures and purposes with regards to lesser beings. Looking back over the course of the last eight years, I now recognize that this has been an important underlying element of it, with multiple instances of divine invention, encounters with computer "gods", and deity-centered mysteries informing the course of its action. Overall, I think this element has not only helped keep everyone interest but has also helped to make the House of Worms feel distinct from other fantasy campaigns I've refereed. There's a sense that the characters are slowly unraveling some of the bigger mysteries of Tékumel, which is heady stuff.

And that's precisely the source of my occasional worries. Over the course of the campaign, I've given quite some thought to these questions and have come to some tentative conclusions. At any given moment, I'm happy with them. Indeed, I often find them genuinely clever and compelling – to me, if no one else. These conclusions inform my approach to the characters' actions; they're part of the slowly emerging truths of Tékumel. So far, the players have responded well to them, but there's a part of me that worries, "Have I gone too far? Have I ruined this campaign that we've all enjoyed for nearly a decade?"

My anxiety is based, in large part, on the fact that, as I reveal more and the characters come to understand more, I am changing the setting in various ways, or at least changing the players' perspective on it. A few sessions ago, one of the players commented that, in light of new things his character had learned, that character would have to re-evaluate what he believes and wants to do. The player didn't say this ruefully – far from it, in fact. Nevertheless, there was a sense that the character had lost some of his innocence; he could no longer look at Tékumel as he once knew it. This was definitely a moment of growth for the character, but it is also signaled that the campaign had rounded a particular corner and there was no going back.

Have any other referees felt similarly about their campaigns? Have you ever felt that you'd introduce something into a campaign that had changed things in such a way that you worried it might do lasting violence to the campaign? Or is this just another of my overthinking of things?

March 30, 2023

Frustration

There are few things more frustrating than spending time and energy on a blog post about a very interesting topic only to discover, after having nearly completed it, that I'd already written on this exact topic thirteen years ago, but had forgotten I'd done so.

With just shy of 4000 posts in the archive of Grognardia, I suppose this was inevitable. Unfortunately, it seems to be happening more and more lately. Either I'm getting more forgetful or I'm running out of things to say. I'm honestly not sure which is a more frightful prospect.

March 29, 2023

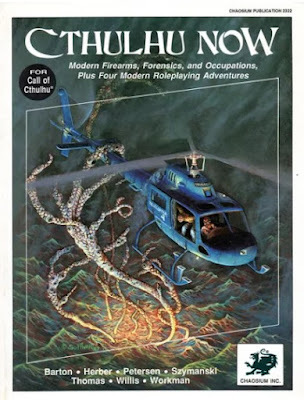

Retrospective: Cthulhu Now

Since its original release in 1981,

Call of Cthulhu

's default setting has been the 1920s. As a result, the venerable horror roleplaying game is inextricably linked to the Jazz Age in the minds of most gamers. This linkage is, however, a mere accident of history, a consequence of the fact that most of H.P. Lovecraft's tales, including the eponymous "The Call of Cthulhu," were written and published during that decade.

Since its original release in 1981,

Call of Cthulhu

's default setting has been the 1920s. As a result, the venerable horror roleplaying game is inextricably linked to the Jazz Age in the minds of most gamers. This linkage is, however, a mere accident of history, a consequence of the fact that most of H.P. Lovecraft's tales, including the eponymous "The Call of Cthulhu," were written and published during that decade. Of course, to Lovecraft and his readers, his stories of cosmic horror were set, not in the past, but in the present. Indeed, much of their power comes from the juxtaposition of ancient terrors and the perceived progress of the "modern world." On some level, it's thus always been a bit odd that Sandy Petersen Call of Cthulhu chose to retain the 1920s setting for the game rather than the here and now. Had he lived longer, I have little doubt that Lovecraft would have set his stories in whatever was the current date at the time, since that had (mostly) been his practice since he first took up writing.

At least some players of Call of Cthulhu agreed with this perspective, since, almost from the very beginning, I knew of those who'd set their campaigns in the then-present rather than the '20s. Indeed, within only a couple of years of the game's initial publication, White Dwarf magazine presented a two-part article by Marcus L. Rowland entitled "Cthulhu Now!". As I noted in my discussions of the issues in which it appeared, I adored Rowland's too-brief stab at the topic of updating Call of Cthulhu for the 1980s and readily made use of its rules expansions and additions. At the time, I thought a more contemporary setting made much more sense than the 1920s, which, in my gaming circle at least, we tended to associate with RPGs like Gangbusters.

So, when Chaosium published a new softcover rules supplement for Call of Cthulhu in 1987 with the title Cthulhu Now, I assumed that it was simply a further expansion of Rowland's original article and happily snapped it up from my local hobby shop without ever bothering to look inside its covers. When I did, I discovered that it was a similar but not entirely identical beast to that two-part White Dwarf offering of a few years prior. The name of Marcus Rowland was nowhere to be found. Instead, like so many Chaosium products of old, the book bore the bylines of no fewer than seven different authors, including Sandy Petersen himself. Over the years, I have long wondered why a book bearing an identical title (sans the exclamation point) and focusing on similar subjects doesn't even acknowledge Rowland's original. This is a gaming mystery that remains unsolved.

What's immediately noticeable about Chaosium's version of Cthulhu Now is that, of its 128 pages, less than a third are devoted to rules additions, alterations, or expansions – and more than a third of that is devoted to new equipment, particularly firearms. None this material is bad, let alone useless, but it feels rather beside the point. Of course the 1980s has lots of technology that didn't exist in the 1920s and it's important to provide game stats for the most significant examples of that technology. In my opinion, though, what really separates the present – whether the 1980s or the 2020s – from the 1920s, at least from the perspective of a Call of Cthulhu campaign, are social/cultural/political differences that would have an impact on how investigators might go about their business. We get a few nods in this direction, most notably in the form of a solid section on forensic pathology, but it's still not enough to aid the Keeper in setting his campaign in the modern era.

I suspect that Chaosium felt that the four scenarios Cthulhu Now includes would do a lot of the heavy lifting in this regard, providing practical examples of what a modern day CoC adventure might be like. As presented, the adventures contain a lot of good ideas and concepts, but they're often poorly implemented and verge on railroads at times – a common problem in Call of Cthulhu scenarios – so their utility as guides is limited. That said, they do show off the possibilities of contemporary gaming, ranging from an underwater investigation to dream research to space exploration and more. Admittedly, all four scenarios feel a bit dated now, largely because nearly four decades have passed since the book's publication and technology and society have continue to change.

Ultimately, though, I think my dissatisfaction with Cthulhu Now has more to do with my own ambivalence about setting Call of Cthulhu in the present day. As I stated earlier, this is something I've always felt made sense and that I instinctively wanted to do with the game. Yet, conversely, there's no denying that the Cthulhu Mythos, at least as its popularly conceived, has become almost quaint in its vision of cosmic horror, so quaint that it only really works well as a period piece. That's not to say that a contemporary approach to Lovecraftian horror is impossible, only that doing so effectively requires a lot more work and imagination than most people realize and Cthulhu Now is largely lacking in both.

March 28, 2023

Individually Approved

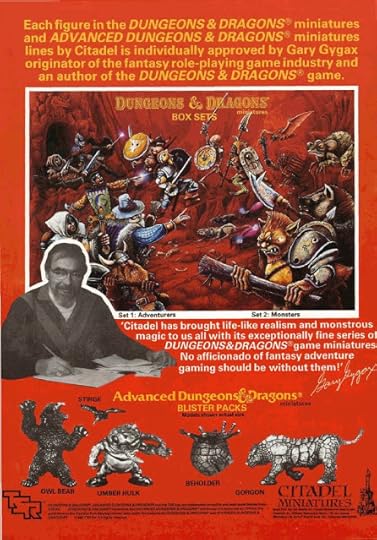

Earlier this month, I wrote a post about the lines of D&D and AD&D miniatures that Citadel briefly produced between 1985 and '86. As one might have expected, the line was heavily advertised in the pages of White Dwarf. In issue #69, the above ad appeared and it really caught my eye, not only for its Warhammer-esque artwork and photos of the actual miniatures themselves, but also for its placement of Gary Gygax himself within it.

Earlier this month, I wrote a post about the lines of D&D and AD&D miniatures that Citadel briefly produced between 1985 and '86. As one might have expected, the line was heavily advertised in the pages of White Dwarf. In issue #69, the above ad appeared and it really caught my eye, not only for its Warhammer-esque artwork and photos of the actual miniatures themselves, but also for its placement of Gary Gygax himself within it.This particular image of Gygax is one I am sure I have seen before in another context – indeed, possibly in another advertisement – but my aged brain is simply unable to recall it at the moment. Regardless, I think the prominence of Gygax, "originator of the fantasy role-playing game industry and an author of the DUNGEONS & DRAGONS®," is noteworthy, especially in September 1985, a mere thirteen months prior to his formal departure from TSR Hobbies.

The supposed fact that Gygax had "individually approved" each figure is presented as a point in favor of these lines and I imagine that, in the minds of many, it might well have been so. I don't think there's ever been a figure in the history of roleplaying games quite like Gary Gygax. He was likely the first – and only – celebrity the hobby has ever known, someone recognizable by name and face and opinion in a way that I don't think anyone, before or since, has ever been. To some, he was a hero, to others, a devil, but there can be little doubt that we shall not see his like again.

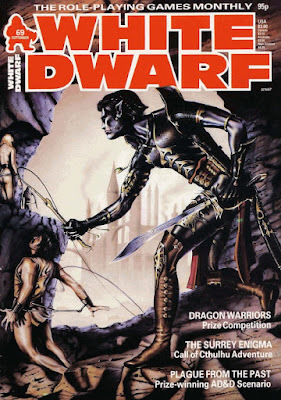

White Dwarf: Issue #69

Issue #69 of White Dwarf (September 1985) is one of which I have no memory whatsoever. As I mentioned last week, I'm now looking at issues published after I ceased my subscription to the magazine, so my recollections of them are generally hazy. In this particular instance, they're non-existent, so my reading in preparation for this post may well be the first time I've ever set eyes on the issue. The cover is another by Mark Bromley, featuring what would appear to be a dark elf (drow?) lashing a slave under his charge.

Issue #69 of White Dwarf (September 1985) is one of which I have no memory whatsoever. As I mentioned last week, I'm now looking at issues published after I ceased my subscription to the magazine, so my recollections of them are generally hazy. In this particular instance, they're non-existent, so my reading in preparation for this post may well be the first time I've ever set eyes on the issue. The cover is another by Mark Bromley, featuring what would appear to be a dark elf (drow?) lashing a slave under his charge. Ian Livingstone's editorial focuses on the tenth anniversary of the Games Day convention. He notes not just the long queues to enter the event, but also the fact that its attendees now number in the thousands rather than the hundreds that first turned out for it in 1975. I have a vague memory that Games Workshop brought a version of Games Day to Baltimore sometime during the '80s, though I never attended it. I wonder how similar it might have been to the original in the UK.

The issue kicks off with "Rationale Behavior" by Peter Tamlyn. The article is actually an extended discussion of the concept of alignment within Dungeons & Dragons, including its limitations. Tamlyn then notes that GW's superhero game, Golden Heroes, includes a series of "campaign ratings" that measure a character's relationship with the in-game world, such as, for example, Public Status and Personal Status. These ratings, he contends, do a better job of describing a character than a simplistic alignment system. For that reason, Tamlyn puts forward an alternative to alignment that takes into account a character's religious attitudes, social status, public piety, and so on in order to give a fuller picture of his place in the fantasy setting. It's an intriguing idea and not without some advantages over alignment, though its use requires considerably more work on the part of both the referee and the player. Still, it was a thought-provoking article.

The second part of Peter Blanchard's "Beneath the Waves" appears, focusing this time on "developing civilizations." As with its predecessor, this article's purpose is to consider the ramifications of life underwater in a fantasy setting. Also like its predecessor, the second installment is well-done but much too brief. Blanchard wisely looks at many of the obvious considerations of the submarine environment, along with less apparent ones, like writing, working metal, construction, and even magic. Unfortunately, most of these topics get a couple of paragraphs at most – better than nothing but still barely scratching the surface of a huge topic. The article would have done well with more examples of how to employ its principles, I think.

"Open Box" starts off with short reviews of three different adventure modules for TSR's Marvel Super Heroes: Secret Wars (7 out of 10), Lone Wolves (6 out of 10), Cat's-Paw (6 out of 10). Interestingly, reviewer Marcus L. Rowland calls Cat's-Paw his favorite of the three and yet it does not receive the highest rating of the three, another indication that these scores were given not by the reviewer but by someone else on the White Dwarf staff. Also reviewed is Toon Strikes Again (8 out of 10) and the boardgame, Chill: Black Morn Manor (8 out of 10), two products with which I have no direct familiarity, though I remember being very intrigued by advertisements for the latter. Finally, there's a review for TSR's Conan Role-Playing Game. The reviewer, Peter Tamlyn, is generally impressed with the game (7 out of 10), but his enthusiasm is dampened by its many editing, proofreading, and typesetting errors. He hopes that there might be a second edition that corrects its many deficiencies..

Dave Langford continues to do his thing in "Critical Mass." At this stage, I find I most enjoy his reviews when he shares my own prejudices, hence why the only things I can remember about this month's installment is his skewering of both Barbara Hambly and Piers Anthony, two writers whose popularity has always baffled me. "Close Encounters" by Ian Marsh similarly held little interest for me. Marsh presents what he thinks RuneQuest really needs: an expansion of the game's strike rank system that takes into account weapon length ...

The saga of "Thrud the Destroyer" concludes as it was destined to do so: with Thrud and his fellow mercenaries screwing things up for their peasant patrons. "The Travellers" includes more character write-ups, including game statistics, this time for the characters of Hayes and Gavin. "Gobbledigook" likewise reappears. "The Surrey Enigma" is a solid, if inconsequential, Call of Cthulhu adventure by Marcus L. Rowland (did he write everything in WD in the mid-80s?), in which the characters investigate unfounded rumors of witchcraft only to discover something much more sinister. I find it fascinating that the adventure takes the time to explain the old British, pre-decimal currency system to readers. Had its existence already been forgotten by 1985?

"Plague from the Past" by Richard Andrews is an AD&D adventure for 5th–7th level characters. The scenario is clever in a folkloric way that fantasy adventures frequently are not. The village in which it takes up is built atop the body of a long-dead giant and present-day actions are resulting in the giant's restoration to life. Good stuff! "Battle Stations" by J. Evans and E. Wilson presents an alternate – and more complex – damage system for use with Traveller's High Guard. To each his own, but I cannot say I see the appeal. Mind you, the older I get, the more convinced I am that simple, straightforward rules are usually best if your goal is to sustain a campaign long-term, so I am probably biased against articles of this sort.

"The Starlight Pact" by Peter Haines and David Smith is the latest installment of the venerable "Fiend Factory" column. Up till now, "Fiend Factory" showcased new monsters for use with Dungeons & Dragons. This month, the column instead presents five superheroes for use with Golden Heroes, each of which is inspired by a miniature figure produced by Citadel. The times they are indeed a-changin' at White Dwarf. "Shopping for Inspiration" by Joe Dever briefly offers up the names and addresses of stores that sell supplies of interest to miniatures painters, along with the usual tantalizing photos of some of the author's own handiwork. Finally, "Poison" by Graeme Davis presents yet another "new and easy-to-use" system for handling toxins in AD&D – once again, more complexity than I'd ever need, but your mileage may vary.

March 27, 2023

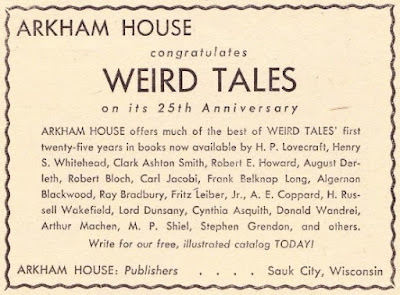

Arkham House Congratulates Weird Tales

As I noted in my earlier post, "The Master of the Crabs" first appeared in the 25th anniversary issue of Weird Tales. You can take a look at the contents of the entire issue here, including its advertisements. Among those ads is this one, placed by none other than Arkham House:

This is a good reminder of just how significant to the history of fantasy and science fiction Arkham House once was. It's also a reminder of just how ephemeral tastes can be. Of the nearly twenty authors listed, less than half of them have had any lasting literary influence and fewer still remain well known and read today. However much I might wish to decry this, it remains a fact and will likely only become truer as the decades grind on.

This is a good reminder of just how significant to the history of fantasy and science fiction Arkham House once was. It's also a reminder of just how ephemeral tastes can be. Of the nearly twenty authors listed, less than half of them have had any lasting literary influence and fewer still remain well known and read today. However much I might wish to decry this, it remains a fact and will likely only become truer as the decades grind on. Pulp Fantasy Library: The Master of the Crabs

Something that's often overlooked when discussing the "Big Three" of Weird Tales is that, while both Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft were dead by March 1937, Clark Ashton Smith lived for another quarter-century. Now, it is true that, following the death of his own father in December 1937, CAS largely abandoned fiction writing in favor of both his original avocation, poetry, and sculpture, he nevertheless continued to write fiction, albeit with far less industry than he had during the fruitful period between 1926 and 1935. Often, he did so at the behest of others, who encouraged him to pen new stories for his most famous literary cycles.

Something that's often overlooked when discussing the "Big Three" of Weird Tales is that, while both Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft were dead by March 1937, Clark Ashton Smith lived for another quarter-century. Now, it is true that, following the death of his own father in December 1937, CAS largely abandoned fiction writing in favor of both his original avocation, poetry, and sculpture, he nevertheless continued to write fiction, albeit with far less industry than he had during the fruitful period between 1926 and 1935. Often, he did so at the behest of others, who encouraged him to pen new stories for his most famous literary cycles.

A good example of this is "The Master of the Crabs," a tale of Zothique he wrote after being asked by Associate Editor Lamont Buchanan to contribute to the upcoming 25th anniversary issue of Weird Tales. This issue would appear in March 1948, making it the second to last Zothique story Smith ever wrote (the last being "Morthylla"), though, like so many of his later fiction efforts, it was based on an idea he'd had years earlier (in this case, 1932 or earlier). Though "The Master of the Crabs" is by no means one of Smith's best works, it's both comparatively short and contains enough imaginative elements to make it worthwhile.

The story is almost Vancian in its set-up: two rival sorcerers – Mior Lumivix and Sarcand – contend for possession of "the fabulous chart of Omvor," which

was a thing that many generations of wizards had dreamt to find. Omvor, an ancient pirate still renowned, had performed successfully a feat of impious rashness. Sailing up a closely guarded estuary by night with his small crew disguised as priests in stolen temple-barges, he had looted the fane of the Moon-God in Faraad and had carried away many of its virgins, together with gems, gold, altar-vessels, talismans, phylacteries and books of eldritch elder magic. These books were the gravest loss of all, since even the priests had never dared to copy them. They were unique and irreplaceable, containing the erudition of buried aeons.

Omvor's feat had given rise to many legends. He and his crew and the ravished virgins, in two small brigantines, had vanished ultimately amid the western seas. It was believed that they had been caught by the Black River, that terrible ocean-stream which pours with an irresistible swiftening beyond Naat to the world's end. But before that final voyage, Omvor had lightened his vessels of the looted treasure and had made a chart on which the location of its hiding-place was indicated. This chart he had given to a former comrade who had grown too old for voyaging.

No man had ever found the treasure. But it was said that the chart still existed throughout the centuries, hidden somewhere no less securely than the loot of the Moon-God's temple. Of late there were rumors that some sailor, inheriting it from his father, had brought the map to Mirouane. Mior Lumivix, through agents both human and preterhuman, had tried vainly to trace the sailor; knowing that Sarcand had the other wizards of the city were also seeking him.

Despite this, "The Master of the Crabs" is told in the first person from the perspective of neither of the wizards, but of Manthar, the apprentice of Mior Lumivix, whose primary task up to now has been the grinding of ingredients for his master's "most requested love-potions." Manthar's youth and inexperience make him a good viewpoint character, just as his ignorance of arcane matters and the details of the quarrel between Sarcand and Mior, provide excellent excuses for Mior – and Smith – to pontificate amusingly to the reader.

By occult means, Mior had spied upon his rival, in the process learning of his recent actions and whereabouts.

"Tonight I did a dangerous thing, since there was no other way. Drinking the juice of the purple dedaim, which induces profound trance, I projected my ka into his elemental-guarded chamber. The elementals knew my presence, they gathered about me in shapes of fire and shadow, menacing me unspeakably. They opposed me, they drove me forth... but I had seen — enough."

Sarcand, Mior explains, had traveled by boat westward to the island of Iribos, which in the past had been known as the Island of Crabs. Urging Manthar to gird himself with weapons like himself, Mior decides to set out after Sarcand.

"My familiars warned me that Sarcand had left his house a full hour ago. He was prepared for a journey, and went wharfward. But we will overtake him. I think that he will go without companions to Iribos, desiring to keep the treasure wholly secret. He is indeed strong and terrible, but his demons are of a kind that cannot cross water, being entirely earthbound. He has left them behind with moiety of his magic. Have no fear for the outcome."

With that, the master and his apprentice set out for Iribos – and their confrontation with Sarcand. Their journey to the island takes three days. Iribos is rocky and covered with sparse "funereal-colored vegetation." It is also uninhabited – by human beings at any rate – which only heightens the seeming danger of the place. Rowing closer, the pair eventually spy "the low, broad arch of a cavern-mouth" that Mior Lumivix takes to be worthy of closer inspection. Because of the highness of the tide, piloting their sailing vessel past the archway proves difficult. The low roof of the cavern snaps the boat's mast and, in doing so, causes additional damage that the vessel, which soon takes on water and begins to sink.

The master and apprentice survive by swimming and make their way into the dark cave beyond. Inside is a stretch of sand and a wrecked boat not unlike their own. They also saw "two reclining figures," which they approached warily, their weapons hidden beneath their clothing.

As we neared the figures, the appearance of a yellowishbrown drapery that covered them resolved itself in its true nature. It consisted of a great number of crabs who were crawling over their half-submerged bodies and running to and fro behind a heap of immense boulders.

We went forward and stopped over the bodies, from which the crabs were busily detaching morsels of bloody flesh. One of the bodies lay on its face; the other stared with half-eaten features at the sun. Their skin, or what remained of it, was a swarthy yellow. Both were clad in short purple breeks and sailor's boots, being otherwise naked.

'What hellishness is this?" inquired the Master. "These men are but newly dead — and already the crabs rend them. Such creatures are wont to wait for the softening of decomposition. And look — they do not even devour the morsels they have torn, but bear them away."

It's here that the story approaches its climax, leading to a fairly satisfying, if not entirely unexpected, conclusion, one very much in keeping with Smith's penchant for black humor.

Compared to his best stories of Zothique, "The Master of the Crabs" is undoubtedly one of Clark Ashton Smith's more modest efforts. Nevertheless, it contains all of the elements one expects of such a tale – mystery, mounting horror, baroque vocabulary, and a touch of wit – that I think it worth reading at least once, especially if you've never done so before. My primary pleasure in reading it are its little details about Zothique and its geography and peoples, as it's my favorite of Smith's fictional settings. Your mileage may vary, of course.

March 23, 2023

The Graveyard and the Satanic Pit

The Graveyard as it exists today, courtesy of Google MapsAt the start of Fourth Grade, my family moved into the house I most strongly associate with my childhood. The house was part of a new development in an area that had previously been farmland, so there were lots of wild, largely untamed woods nearby, not to mention creeks and ponds. My friends and I spent many an hour exploring these places, sometimes as part of a game we called "hide and seek tag" and sometimes just for the fun of it. We encountered lots of fascinating – and sometime frightening – things in those woods, including plenty of spiders through whose webs we'd regularly run in the course of our adventures. There was the occasional snake too, though never the dreaded water moccasin about whom we'd heard many tales (probably because it's not native to the region, but such little details didn't stop us from fearing it).

The Graveyard as it exists today, courtesy of Google MapsAt the start of Fourth Grade, my family moved into the house I most strongly associate with my childhood. The house was part of a new development in an area that had previously been farmland, so there were lots of wild, largely untamed woods nearby, not to mention creeks and ponds. My friends and I spent many an hour exploring these places, sometimes as part of a game we called "hide and seek tag" and sometimes just for the fun of it. We encountered lots of fascinating – and sometime frightening – things in those woods, including plenty of spiders through whose webs we'd regularly run in the course of our adventures. There was the occasional snake too, though never the dreaded water moccasin about whom we'd heard many tales (probably because it's not native to the region, but such little details didn't stop us from fearing it).Outside of the wooded areas, the housing development was exactly what you'd expect from suburban America in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It wasn't exactly like something out of a Steven Spielberg movie, but it's in the same ballpark. My friends and I spent nearly all of our time outside, even during the peak humidity of August and September, though we'd often visit one another's back yards on a rotating basis, depending on whose deck was most in the shade at any given hour. This is where we'd gather to play Dungeons & Dragons and other roleplaying games, rolling dice – often unsuccessfully – across the tops of picnic tables and contending with the seemingly inexhaustible supply of mosquitos, wasps, and Japanese beetles that swarmed during the warmer months.

In the midst of the development, there was one area that remained inexplicably wild: the Graveyard. That's not it's real name; that's what my friends and I called it. On a cul-de-sac street behind where we all lived, there was this low hill, covered in patchy grass and sparse trees. For no obvious reason, the place had been left intact rather than being leveled and having several more houses built on it. Somehow, the legend had grown up that the reason the hill had been left alone is that it was the burial place of members of the family who'd originally owned the land and, therefore, could not be disturbed, hence why we – and all the other kids in the neighborhood – called it the Graveyard.

I should stress that there was only the most circumstantial evidence to support this theory. Indeed, to call it a "theory" is being charitable. At the same time, there was clearly something weird about this little hill. Not only was it still there when so much else in the area had been cleared to make way for homes, but the newsletter of the neighborhood association, which handled things like snow removal and garbage collection, often included notices that children were not to play on this hill, though no reasons for the prohibition were given. Needless to say, my friends and I spent untold hours atop the hill during the warmer months. Shaded by its trees, we even devoted ourselves to finding "proof" that the place was indeed a graveyard as we imagined it to be. One of my friends brought a shovel to dig, to little avail.

The Graveyard was not the only mysterious locale in my neighborhood. Within the remaining woods, there was another place that captured our youthful imaginations: the Satanic Pit. The Pit was a circular bit of raised concrete, maybe three or four feet across, with a metal grate across its top. If you looked down into it, you could see there were metal handholds along one side and that it extended some unknown distance into the dark. At certain times, steam would rise from it, often smelling quite foul. I presume the Pit was actually connected to the local sewer system in some fashion, but, to us, it was always the Satanic Pit. Despite our best efforts, we never managed to remove the grate from the top of the thing and our dreams of descending into the unknown depths were forever barred to us.

The Graveyard and the Satanic Pit linger in my memories even now. I sometimes even have dreams of going down into the Pit with my friends and then getting lost or being unable to return to the surface again for some reason. It's funny how these formative experiences can continue to have a hold on you many decades later. I'm actually quite grateful that the little world of my youth included mysterious places like these. They gave me a chance to explore, to flirt with "danger," and, above all, to imagine. I have little doubt that the hours I spent on or near the Graveyard and the Pit, not to mention pondering their presumed secrets, played a role in my ready embrace of Dungeons & Dragons when I eventually encountered it. For that, I will always be grateful.

March 22, 2023

Happy Birthday, William Shatner

Unbelievably, today marks the 92nd birthday of William Shatner, whom I – and likely everyone else – will forever remember for his portrayal of James Tiberius Kirk, captain of the U.S.S. Enterprise during the original run of the science fiction series Star Trek and its subsequent spin-offs.

Unbelievably, today marks the 92nd birthday of William Shatner, whom I – and likely everyone else – will forever remember for his portrayal of James Tiberius Kirk, captain of the U.S.S. Enterprise during the original run of the science fiction series Star Trek and its subsequent spin-offs. As I have mentioned before, Star Trek was my original fandom. I was introduced to it in the mid-1970s through the influence of my paternal aunt and godmother, who was a teenager when Star Trek was first broadcast. Indeed, I attribute many of my earliest interests, whether it be science fiction or cryptozoology, to the time she spent with me as a child. Every Saturday, I used to visit my grandparents, where my aunt still lived before she married, and we'd watch reruns of Star Trek on a local independent TV station. These are among my most cherished childhood memories and William Shatner is a big part of why.

Being a bookish and generally nerdy kid, you'd have thought that Leonard Nimoy's Spock would have been my role model. While I loved Spock, Captain Kirk was who I wanted to be, probably because he was so different from myself – courageous, self-assured, decisive, and, above all, protective of his friends and crew. Kirk was everything I hoped I might someday be and Shatner breathed life into him in a way no one could have.

Nowadays, I know it's more or less required that we sneer at Shatner as a big, fat ham of an actor, but, even with the benefit of an adult's perspective, I still think his portrayal of Jim Kirk is phenomenal. Shatner imbued Kirk with the fundamental decency and indeed humanity that are vital to the character's appeal. Far from being the swaggering, overbearing, tin-plated dictator with delusions of godhood of many people's imaginations, Shatner gave Kirk a degree of thoughtfulness and sensitivity that is often underappreciated. I didn't fully recognize this as a child; I only knew that I liked Kirk and wanted to be more like him, which I think would be high praise for any actor.

Happy Birthday, Mr Shatner! My younger self owes you a lot.

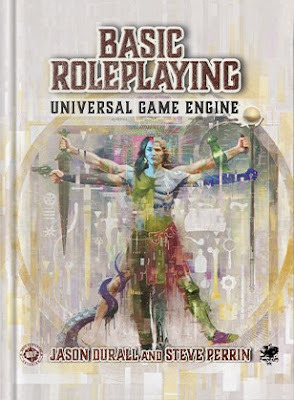

Basic Roleplaying: The Universal Game Engine

Over at their official blog, Chaosium recently announced that a new edition of

Basic Role-Playing

– or should I say Basic Roleplaying, since the old school hyphenation is no more? – is on the way, with a PDF version appearing next month and a hardcover release sometime later this year. This edition represents not only an updating of the popular and successful BRP rules, but also the first time that these rules have been released as royalty-free open content.

Over at their official blog, Chaosium recently announced that a new edition of

Basic Role-Playing

– or should I say Basic Roleplaying, since the old school hyphenation is no more? – is on the way, with a PDF version appearing next month and a hardcover release sometime later this year. This edition represents not only an updating of the popular and successful BRP rules, but also the first time that these rules have been released as royalty-free open content. After the brouhaha earlier this year about the status of the Open Game License, I'm not at all surprised that Basic Roleplaying is being released under the terms of the Open RPG Creative License (ORC) created by Paizo. As I recall, Chaosium was an early supporter of this alternate license and it appears their commitment to it has not wavered. I'll admit I haven't been following the development of ORC at all since its initial announcement, so I can't say for certain if BRP is the first significant RPG to be released under its terms or not. Regardless, the publication of an open version of this venerable and respected ruleset is significant.

As an admirer of the original, I'm happy to see BRP continue to thrive well into the 21st century, though I still hold out hopes that Chaosium might one day publish a slimmer version of it more akin to the one included in my 1st edition Call of Cthulhu boxed set way back in 1981. In any case, I'll be keeping an eye on this and hope it might lead to a wider appreciation of these classic roleplaying game rules.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers