James Maliszewski's Blog, page 76

May 8, 2023

A Question of Presentation

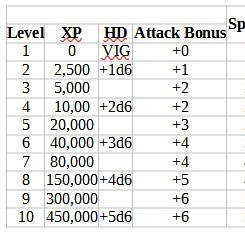

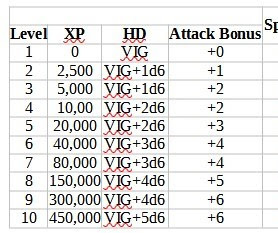

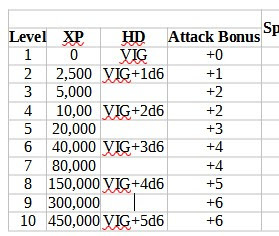

I'm putting the finishing touches on the latest draft of the character classes for Secrets of sha-Arthan. In doing so, I'm finding myself befuddled by the clearest way to present certain bits of rules information. A good case in point is the presentation of accumulated hit dice by level.

At 1st level, all classes begin with a number of hit points equal to their Vigor (VIG) score. At 2nd level, all classes receive an additional number of hit points equal to the results of a random roll. Additional random rolls are made at every even level thereafter (4th, 6th, etc.), while no new hit points are gained at odd levels. What's the best way to present this?

Here's Option 1:

Here, I only include an entry under HD (Hit Dice) when the character adds something to his total. However, this might make the chart less useful for generating NPCs at odd levels, since the referee will need to look to the line below for the number of dice to add to the Vigor total. It's a small thing, admittedly, but it could be an issue.

Here, I only include an entry under HD (Hit Dice) when the character adds something to his total. However, this might make the chart less useful for generating NPCs at odd levels, since the referee will need to look to the line below for the number of dice to add to the Vigor total. It's a small thing, admittedly, but it could be an issue.Option 2 tries to be more clear:

My worry, though, is that, by including an entry on every line, it might be possible to misinterpret each one as additive to all its predecessors.

My worry, though, is that, by including an entry on every line, it might be possible to misinterpret each one as additive to all its predecessors.Option 3:

This option potentially still has the same potential problem as Option 1, but it avoids those of 2, or at least I hope it does. That's the real difficulty here: I've been staring at this stuff so long and thinking about it so much that I sometimes see problems where there aren't any while simultaneously missing those that might be staring me in the face.

This option potentially still has the same potential problem as Option 1, but it avoids those of 2, or at least I hope it does. That's the real difficulty here: I've been staring at this stuff so long and thinking about it so much that I sometimes see problems where there aren't any while simultaneously missing those that might be staring me in the face. Ultimately, I simply want a presentation that's clear, easy to understand, and useful. I'd appreciate any thoughts on the best way to achieve this.

Live or Die: The Choice is Yours!

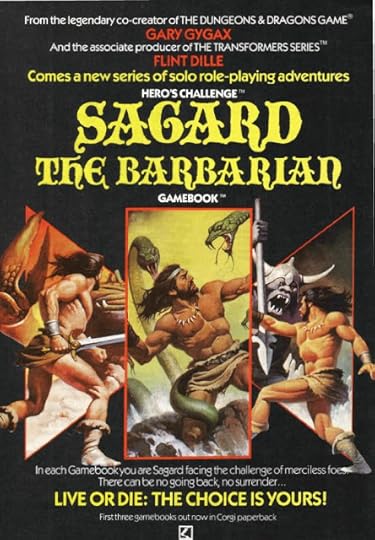

The Sagard the Barbarian gamebooks are interesting artifacts from the mid-1980s. Co-authored by Gary Gygax and Flint Dille, the series consisted of four books published between 1985 and 1986 by Pocket Books in the USA and Corgi in the UK.

There are two aspects of these books that continue to intrigue me. The first is that they were released not by TSR by "mainstream" publisher(s). The '85 to '86 period coincides with Gygax's Cent-Jours, when he briefly seized control of TSR once again before his departure in October 1986. At the time, TSR was a mess on every level, so I can't help but wonder if the decision to publish these books outside of TSR is reflective of the chaos at the company. On the other hand, I also find myself wondering whether Gygax did this as an insurance policy against the demise of TSR, which was a very real possibility at the time. By publishing them elsewhere, he could safeguard his remuneration in a way he might not have been able to had TSR published them.

There are two aspects of these books that continue to intrigue me. The first is that they were released not by TSR by "mainstream" publisher(s). The '85 to '86 period coincides with Gygax's Cent-Jours, when he briefly seized control of TSR once again before his departure in October 1986. At the time, TSR was a mess on every level, so I can't help but wonder if the decision to publish these books outside of TSR is reflective of the chaos at the company. On the other hand, I also find myself wondering whether Gygax did this as an insurance policy against the demise of TSR, which was a very real possibility at the time. By publishing them elsewhere, he could safeguard his remuneration in a way he might not have been able to had TSR published them.The other aspect of the Sagard books that's notable is that, in the first two, they're explicitly set within the World of Greyhawk. The later books, however, shift away from having any clear Greyhawk connections. This is somewhat similar to what happened to Gygax's Gord the Rogue series, whose final volumes were published after he left TSR through his new company, New Infinities. Those later volumes take place in a palimpsest version Greyhawk, with many names changed for legal reasons having to do with the terms of his departure. For this reason, I have a strange fascination with these late Gygax works, if only to ponder how they might have fit into his overall oeuvre had events not gone as they did in 1986.

May 7, 2023

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Seeker in the Fortress

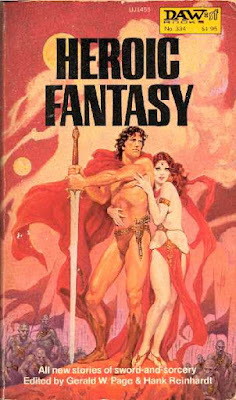

Continuing with my tour of Manly Wade Wellman's tales of Kardios of Atlantis, we come to the fourth in the series, "The Seeker in the Fortress." Like its predecessors, this story first appeared in an anthology, in this case Heroic Fantasy, edited by Gerald W. Page and Hank Reinhardt and published by DAW in 1979. Also like its predecessors, the story takes a well-worn sword-and-sorcery plot – the beautiful princess held against her will by and in need of rescuing – and develops it in unexpected ways. This is, I think, where Wellman's genius lies and why the adventures of Kardios have entertained me far more than I had expected they would.

Continuing with my tour of Manly Wade Wellman's tales of Kardios of Atlantis, we come to the fourth in the series, "The Seeker in the Fortress." Like its predecessors, this story first appeared in an anthology, in this case Heroic Fantasy, edited by Gerald W. Page and Hank Reinhardt and published by DAW in 1979. Also like its predecessors, the story takes a well-worn sword-and-sorcery plot – the beautiful princess held against her will by and in need of rescuing – and develops it in unexpected ways. This is, I think, where Wellman's genius lies and why the adventures of Kardios have entertained me far more than I had expected they would."The Seeker in the Fortress" opens, not with Kardios wandering into some new land or stumbling upon some odd situation but with the description of the titular fortress, which, as the reader soon learns, is the sanctum of a powerful wizard.

Trombroll the wizard had set his fortress in what had been a small, jagged crater, rather like an ornate stopper in the crumpled neck of a wineskin. Up to it on all sides came the tumbled, clotted lips of the cone. Above and within them it lodged, a sheaf of round towers with, on the tallest, a fluttering banner of red, purple and black. At the lowest center, where the fitted gray rocks of the walls fused with the jumbled gray rocks of the crater, stood a mighty double door of black metal. Slits in the towers seemed ready to rain point-blanketed missiles, smoking floods of boiling oil. In this distance rose greater heights, none close enough to command the fortress.

As a stylist, Wellman is nowhere near the equal of Howard, Leiber, or Vance, but he often pens passages like this, which are both evocative and nicely set the scene.

Waiting outside Trombroll's fortress is Prince Feothro of Deribana, who "stood among his captains and councilors and shrugged inside his elegant armor." Coming to greet him is the wizard's herald, dressed "in elaborate ceremonial mail." The herald reminds the prince that his master is "supreme in magic" and that "the winds and the thunder fight his battles." Despite this bombast, Feothro remains unimpressed.

"Trombroll has plagued the world long enough," returned Feothrro, sternly enough. "He threatens plague and famine, and demands tribute to hold them back. Tell him we've come to destroy him. These armies are the allied might of Deribana and Varlo, sworn to end Trombroll's reign of evil. Varlo's King Zapaun is as my father, has pledged his thrice lovely daughter, the Princess Yann, to be my consort. Let Trombroll come out and fight."

"Why should he?" inquired the herald. "We have wells of water, stores of provisions. And we also have that exemplary triumph of beauty, the Princess Yann herself."

"Princess Yann!" howled Feothro. "You lie!"

All looked aloft. Two guards were visible, escorting between them a slender figure in a bright red garment. Then all three drew back out of sight.

The herald then warns the prince and his assembled host that, should they attempt to storm the castle, "the unhappy princess will die an intricate death even now being invented for her." Feothro is incensed by this and looks to his advisors for a plan that might enable him to defeat Trombroll without bringing about the untimely death of his betrothed.

As if on cue, Kardios enters the story, having just been captured after "prowling here and there among the various commands." Initially, the prince believes him to be one of the wizard's spies, but he soon comes to understand that this Atlantean wanderer, known as "an adventurer among monsters," might offer a way to achieve his goals. Kardios agrees, saying "Maybe I happened along in good time to help you." He tells Feothro not to attempt a siege; instead, he should allow Kardios to find a way into the wizard's fortress on his own to rescue Princess Yann. Though he threatens the Atlantean not to fail, Feothro nevertheless agrees and the story kicks off in high gear.

The remainder of "The Seeker in the Fortress" is great fun, a rollicking pulp fantasy adventure, as Kardios encounters – and overcomes – one problem after another in his quest to free the imprisoned princess. The challenges Wellman sets before Kardios are varied and not all of them can be beaten through brute force or swordplay. Further, the Atlantean prefers less violent solutions when possible: "I don't kill unless I must," he explains to one of his defeated foes. It's an excellent change of pace from the earlier installments in the series, not to mention a terrific reminder of the utility of trickery and charm when sneaking into an evil wizard's lair. This is my favorite story of Kardios so far, not to mention one of the better sword-and-sorcery yarns I've read in some time and I highly recommend it.

May 5, 2023

So You Don't Have To

Loren Rosson, a regular reader of this blog and old school RPG fan, recently put together a ranking of twelve of the original fourteen Dragonlance modules published by TSR between 1984 and 1986 (leaving out only DL 5, Dragons of Mystery, which is a sourcebook, not an adventure, and DL 11, Dragons of Glory, which is a wargame). As I remarked to him when Loren first told me about this project, this is a difficult and thankless job. Despite my own decidedly negative feelings about the entire Dragonlance series, I nevertheless think there's great value in looking at these modules, since, for all my criticisms, a few of them contain genuinely imaginative elements. Likewise, they offer some insight into the changing face of TSR, D&D, and roleplaying games generally during the mid-1980s.

If this interests you at all, head on over to Loren's blog and take a look at what he has to say.

A Surfeit of Centipedes

Almost fourteen years ago, I was complaining about the unusually large number of spiders I'd been encountering in and around my home. This year, it's centipedes, specifically house centipedes, which is immediately recognizable by their very long legs. As a species, house centipedes usually emerge from their various hiding places in the springtime, when temperatures start to rise. In my neck of the woods, the spring has been unusually cool and wet. This may explain why I've been running into these little beasts inside the house rather than just outside it.

Almost fourteen years ago, I was complaining about the unusually large number of spiders I'd been encountering in and around my home. This year, it's centipedes, specifically house centipedes, which is immediately recognizable by their very long legs. As a species, house centipedes usually emerge from their various hiding places in the springtime, when temperatures start to rise. In my neck of the woods, the spring has been unusually cool and wet. This may explain why I've been running into these little beasts inside the house rather than just outside it.After watching a centipede scurry into the darkness, its many legs rapidly undulating, I was reminded that giant centipedes are a longstanding monster in Dungeons & Dragons. They're mentioned by name in Volume 2 of OD&D under the header "insects or small animals," but they're not given a distinct entry. The Holmes Basic Set rectifies this. Its entry notes that "these nasty creatures are found nearly everywhere" and that "they are aggressive and rush forth to bite their prey, injecting poison into the wound." The centipedes I've been encountering are anything but aggressive; they flee at the slightest provocation, especially illumination. Like their larger D&D equivalents, house centipedes do possess a poisonous sting, roughly equivalent to a bee's sting in toxicity, hence Holmes's note that "this poison is weak and not fatal (add +4 to saving throw die roll)."

The AD&D Monster Manual describes giant centipedes in nearly identical terms to Holmes, presumably because they were in production alongside one another. Moldvay, meanwhile, ups the ante on the creature's poison: "Their bite does no damage, but the victim must save vs. Poison or become violently ill for 10 days. Characters who do not save move at ½ speed and will not be able to perform any other physical action." Ignoring its entomological error – centipedes don't bite; they sting – Moldvay's description makes giant centipedes a bit more of a genuine threat, akin to the other verminous monsters of D&D.

I find it fascinating that AD&D 2e continues to boost the danger of giant centipedes, which it calls "loathsome, crawling arthropods that arouse almost universal disgust from all intelligent creatures (even other monsters)." 2e repeats the claim that giant centipedes bite rather than sting, but introduces the notion that, in doing so, it "inject[s] a paralytic poison." This poison "can paralyze a victim for 2–12 (2d6) hours, but is so weak that victims of a centipede bite are permitted a +4 bonus to their saving throw." 2e also introduces two more varieties of giant centipede – huge centipedes and megalocentipedes – to bedevil lower-level characters.

Unlike spiders, which do make me uncomfortable, centipedes, for all their legs, don't frighten me. Mind you, I might feel a bit differently if they were a foot or more long, like those in Dungeons & Dragons, and I saw this horrific visage bearing down on me.

May 4, 2023

How Common Were Long Campaigns?

A topic that I think is worthy of further discussion is the extent to which the contemporary "old school" RPG scene is characterized by varying degrees of hyper-correction to the real and imagined excesses of the subsequent (post-1990 or thereabouts) hobby. For the moment, I want to focus on one area where this hyper-correction might exist: long campaigns. I say "might," because I honestly don't know the extent to which lengthy, multi-year campaigns were all that commonplace in the past, even among the founders of the hobby. Certainly, if you read things like the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide, such campaigns were clearly the ideal, at least in some quarters, but what about the reality? Just how common were long campaigns of the sort that I've been extolling for the last few years on this blog?

By most accounts, the earliest version of what would come to be called the Blackmoor campaign appeared sometime in late 1970 or early 1971. Over the course of the next four to five years, Dave Arneson continued to referee adventures set in Blackmoor, with a rotating roster of players (and characters), though there seems to have been a significant amount of continuity during that time period. Gary Gygax's Greyhawk campaign began sometime in 1972 and continued to be played, off and on, throughout the remainder of the decade, again with a rotating roster of players. Then there's Greg Stafford's Dragon Pass campaign and Steve Perrin's one in Prax, not to mention whatever Marc Miller and the GDW crew were doing in the Spinward Marches.

How many of the foregoing were "long" campaigns in the way we've been talking about them lately? Much depends, I suppose, on how you define both terms. For myself, a "campaign" is a continuous series of adventures/sessions in a fictional setting with a regular, if not necessarily static, set of players. I'm sure people could quibble with almost every aspect of my definition, especially since many of the foundational campaigns of the hobby might not qualify under its terms. Likewise, my definition, for all its specificity, is silent on questions as basic as whether a campaign with multiple referees – like the Greyhawk campaign that was eventually co-refereed by Rob Kuntz – is one campaign or two. Then, there's the Ship of Theseus question of how many of the elements of a campaign's beginning must persist over time for it to qualify as the "same" campaign, to say nothing of what constitutes "long." Is length determined by the calendar, the number of sessions, or the time spent playing?

I think these are all important questions, even if we can't easily agree on the answers. Simply asking them is, in my opinion, a good way to fumble toward a better understanding of this hobby, its parameters, and its history. For example, M.A.R. Barker's Thursday night Tékumel campaign would seem to be a paradigmatic example of a long campaign, lasting as it did, with many of the same players, from the late '70s into the 21st century. Though there are no doubt other examples of similarly long-running campaigns, the "Thursday Night Group" is quite likely the highest profile one of which I know. Its longevity and degree of continuity surpasses that of anything Arneson, Gygax, Stafford, or any of the other founders have the hobby ever achieved. That's no small accomplishment, but is it in any way representative of what a long campaign is or should be?

There's also the question of what RPG players in the wider world beyond were doing. How many of them were involved in long campaigns? Depending on how you want to look at it, I was part of either the second or third wave of roleplayers, entering the hobby at the very end of 1979 and beginning serious play of RPGs in early 1980. My friends and I were young – I would have been 10 years old at the time – and, while we knew older, more experienced gamers and were influenced by them, we mostly forged our own paths. For the most part, that path did not include long campaigns. Instead, we flitted from game to game, playing D&D intensely for a month or two, then doing the same with Gamma World or Traveller or Call of Cthulhu, before returning to D&D or whatever other game caught or fancy at the time.

I doubt we were alone in this sort of behavior and I suspect that, as the RPG industry grew, producing ever more games, our behavior was much more widespread than sticking with one game devotedly for years on end. That's not to say we never played a single game for long stretches of time and to the exclusion of others – we did – but these were exceptions rather than the rule, at least until I attended college. Indeed, it was only with adulthood that I succeeded in refereeing a multi-year campaign with the same players and their characters. All the long campaigns I can recall have occurred after I was in my 20s and I sometimes wonder if the level of attentiveness necessary to maintain campaigns of this sort is only possible after a certain age.

So, how common were long campaigns in the past? I wish I knew, if only because I think it's important to understand the history of the hobby as it was rather than as we wish it were.

May 3, 2023

Retrospective: Ghostbusters

Roleplaying games based on officially licensed properties started appearing quite early in the history of the hobby. FGU's Flash Gordon & the Warriors of Mongo is the first that I can recall, unless you wish to count TSR's Warriors of Mars, which is, in my opinion, something of an edge case – and it wasn't officially licensed at any rate). Others soon followed, like Heritage's Star Trek (and FASA's too!), SPI's

Dallas

, Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu and

Stormbringer

, ICE's

Middle-earth Role Playing

, and many, many more.

Roleplaying games based on officially licensed properties started appearing quite early in the history of the hobby. FGU's Flash Gordon & the Warriors of Mongo is the first that I can recall, unless you wish to count TSR's Warriors of Mars, which is, in my opinion, something of an edge case – and it wasn't officially licensed at any rate). Others soon followed, like Heritage's Star Trek (and FASA's too!), SPI's

Dallas

, Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu and

Stormbringer

, ICE's

Middle-earth Role Playing

, and many, many more. I mention all of this because I think it's sometimes easy to forget, especially on the old school side of the hobby, that gamers have long been quite keen on playing around in fictional worlds originally created for mass media. Much as I valorize the inventive and often idiosyncratic settings unique to RPGs, I'm also a big fan of a couple of games that make use of licensed settings and think the hobby would be diminished without them. If nothing else, licensed roleplaying games can serve as a useful entrée to newcomers.

Though I suspect that Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game, released by West End Games in 1987, is the most well-known (and successful?) licensed RPG ever, at least some of its success depends on another West End RPG, released the year before: Ghostbusters. Subtitled, "A Frightfully Cheerful Roleplaying Game," Ghostbusters is an unexpectedly good game, boasting not just a good sense of humor, as you'd expect, but also a solid and easy to use set of rules. Looking at its designers – Sandy Petersen, Greg Stafford, and Lynn Willis – this should come as little surprise. What still surprises me, though, even after all these years, is that it was Ghostbusters that gave the world not just the core of the system later used to excellent effect in the aforementioned Star Wars RPG, but also gave it the now-ubiquitous dice pool method of resolving in-game actions.

Characters in Ghostbusters have four ability scores, called traits – Brains, Muscle, Moves, and Cool – that are each given a numerical rating representing the number of six-sided dice rolled when making use of that trait. Players can associate a talent with each trait. Talents are more or less skills, like brawl, convince, or parapsychology. When a character makes use of a talent, he gets an additional three dice to add to those already provided by his trait. Other things, like equipment, can add to the pool of dice a player rolls as well. The sum of any roll is then compared to a target number assigned by the referee (called the Ghostmaster), based on its difficulty, success equated with meeting or exceeding the assigned target number.

If you understood the foregoing description of Ghostbusters' game mechanics without any trouble, that's because they're now well-established and commonplace, but that wasn't the case in 1986, when the idea of dice pool was somewhat exotic, at least in the circles in which I moved. As I already mentioned, Star Wars borrowed and further developed this system, which is no surprise, given that the two games were both West End products. What's more remarkable, I think, is that games like Ars Magica, Vampire: The Masquerade (and its sequels), and Shadowrun all evince the direct or indirect influence of Ghostbusters, making its mechanics, along with those of Dungeons & Dragons and Basic Role-Playing, among the most enduring in the history of the hobby.

Ghostbusters included or popularized several other mechanical innovations, such as the use of "brownie points" with which a player could influence the result of dice rolls, potentially blunting some of their negative consequences. "Hero points" of this sort were nothing new by this point. However, Ghostbusters enabled a player to gain more brownie points for his character through good roleplaying and achieving his character's stated goals. I can't say for certain that nothing like this had ever been done before – I'm pretty sure it had been – but, at the time, I found it revelatory. At the opposite end of the scale, the game included the "ghost die," a special six-sider where the 6 was replaced with the Ghostbusters logo. The ghost die is used in every roll and any roll showing the logo indicates a negative consequence of some sort, even if the roll is otherwise successful. Again, it's old hat now; in 1986, though, this was genuinely innovative.

Another aspect of Ghostbusters that I think deserves special praise is its basic premise. Unlike some licensed RPGs, which assume the players will take on the roles of existing characters within the media property, Ghostbusters assumes the players will create their own Ghostbusters, who are franchisees of the original, New York-based Ghostbusters of the 1984 movie. The idea is that the player characters are the local Ghostbusters of their hometown and their adventures should reflect that fact. I think it's a great set-up and, even at the time, I felt that it was a good basis for making more Ghostbusters movies, with each one taking place in a new city with a new cast of characters.

I really enjoyed playing Ghostbusters when it was first released and still look back fondly on it. Sadly, I no longer have my copy and trying to replace it is prohibitively expensive. It's a very underrated RPG for one that is so well designed, influential, and fun. I wish it were more widely known and appreciated today.

May 2, 2023

Secrets

I am continually amazed by just how influential the design of Dungeons & Dragons has been on nearly all roleplaying games that have followed in its wake. Aside from those games descended from or inspired by Chaosium's

Basic Role-Playing

, the vast majority of RPGs include rules for character advancement that make use of experience points in one form or another. Lest there be any confusion, by "experience points," I mean an abstract, numerical measure of a character's achievement the accumulation of which enables said character to improve his abilities or acquire new ones, whether in level-based "chunks" or by using them directly as currency.

I am continually amazed by just how influential the design of Dungeons & Dragons has been on nearly all roleplaying games that have followed in its wake. Aside from those games descended from or inspired by Chaosium's

Basic Role-Playing

, the vast majority of RPGs include rules for character advancement that make use of experience points in one form or another. Lest there be any confusion, by "experience points," I mean an abstract, numerical measure of a character's achievement the accumulation of which enables said character to improve his abilities or acquire new ones, whether in level-based "chunks" or by using them directly as currency. I was pondering this fact recently as I was working on the latest draft of Secrets of sha-Arthan. After a couple of periods of doubt, I've committed myself to a D&D-descended class-and-level design, because it's familiar and easy to use. The experience of refereeing House of Worms over the last eight years using the 1975 Empire of the Petal Throne rules – itself a D&D variant – confirms this to my satisfaction. Given all this, I had initially assumed, without much thought, that I would also be adopting a D&D-style experience system, right down to XP for defeating enemies and accumulating treasure.

But, as I was revising my draft in light of playtest comments and suggestions, I began to wonder: do I need to use experience points at all? Or at least, do I need to use experience points in the same way as Dungeons & Dragons? The truth is, I've never had a problem with D&D's XP system. It does its just well and largely gets out of the way. Does it "make sense" from an in-game perspective? Kinda, sorta, if you squint the right way and don't ask too many probing questions. As I said, I'm largely fine with it and have used EPT's idiosyncratic version of it without much complaint from my players over the course of the campaign. That's why I was (am?) prepared to use it more or less as-is in Secrets of sha-Arthan.

But there was this little voice in the back of my mind telling me I could do better, telling me I could do something that fit both the sha-Arthan setting and the intended focus of game play, namely, the uncovering of secrets. Like Tékumel, which inspired it, sha-Arthan is an ancient world full of mysteries. Things are most definitely not what they seem and my goal from the beginning has been the creation and presentation of a fantasy setting in which unraveling its mysteries lies at the heart of things. Rather than merely delving into the depths for "more and bigger loot," I wanted to emphasize learning more about the setting and its history but in a way that was both approachable and valuable in-game.

Unfortunately, I must confess to being a bit stumped on how best to achieve these two goals. One of the perennial issues of any detail-rich setting, whether it be Glorantha, Tékumel, or Hârn, is degree to which those details become the setting rather than illuminate it. I know far too many self-professed "Tékumel fans" who never actually play in the setting; instead, their hobby consists of talking and thinking about the setting and its encyclopedic details rather than exploring them through play. That's something I do not wish to encourage with sha-Arthan – quite the opposite, in fact, which is precisely why I keep thinking about ways to square this particular circle.

Here's an example of what I'm aiming for. Sorcery is a fact of sha-Arthan and has been for untold millennia but its workings are neither widely understood nor publicly taught. Spell formulae are thus secrets and player character sorcerers can only acquire additional ones through in-game activities, such as finding occult tomes or instruction crystals, joining a cult, or simply convincing another sorcerer to share his knowledge with the PC. Thus, to achieve a higher level, the character must do something in-game, such as, for example, learn a certain number of new spells through his own efforts. In effect, the character is actively involved in the acquisition of the power traditionally associated with gaining a new level and his player simultaneously learns a bit more about the setting in the process.

I very much like this idea and think it opens up a lot of possibilities, but it'll require a lot more work from the referee, who has to consider where the necessary secrets are located within his own campaign, not to mention from me, who has to lay this all out in a way that is easily intelligible to others. There's also the fact that the secrets necessary for every character class to gain levels are as straightforward as they are for sorcerers or adepts, whose level-based abilities derived from spells or psychic disciplines and are, therefore, easier to present as in-game knowledge. What about martial warriors or persuasive scions, to say nothing of the nonhuman Chenot, Ga'andrin, or Jalaka? How do I make a secrets-based advancement system work for them?

I have little doubt I'll eventually find a way to make this idea work. At the moment, though, it's proving a little vexing, because I can clearly see where I want to go with the game. I just don't – yet – know how to get there.

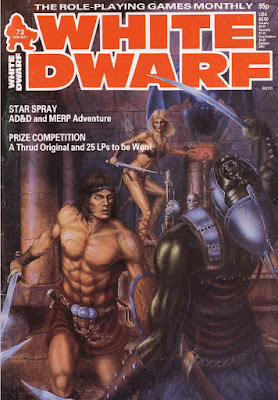

White Dwarf: Issue #73

Issue #73 of White Dwarf (January 1986) features a cover by Lee Gibbons, an artist whose work I recall from various Call of Cthulhu products over the years. Inside, Ian Livingstone boasts of the fact that the UK pharmacy chain, Boots, has "decided to stock role-playing games, Citadel miniatures, and Fighting Fantasy books." He sees this as a major victory that will help "dispel the illusion of [the hobby's] being a weirdos' cult."

Issue #73 of White Dwarf (January 1986) features a cover by Lee Gibbons, an artist whose work I recall from various Call of Cthulhu products over the years. Inside, Ian Livingstone boasts of the fact that the UK pharmacy chain, Boots, has "decided to stock role-playing games, Citadel miniatures, and Fighting Fantasy books." He sees this as a major victory that will help "dispel the illusion of [the hobby's] being a weirdos' cult."

Having grown up in the United States, I find this fascinating. For all the overheated rhetoric about Dungeons & Dragons in certain quarters, RPGs and fantasy games had been readily available in major retail chains across the country since the beginning of the 1980s, if not before. However, Livingstone states that Boots is "the first major chain to stock a large range of rolegames in the country." This surprises me. When I was an exchange student in London in 1987, I had no trouble finding RPGs in most of the bookshops I visited and so assumed they had been a fixture in such places for a long time, as they were in the USA.

"Open Box" reviews Queen Victoria & the Holy Grail, a scenario for Games Workshop's Golden Heroes, which nets a score of 8 out of 10. Also reviewed is another Games Workshop product, Judge Dredd – The Role-Playing Game, which earns a perfect 10 out of 10. I remember wanting a copy of this game for a long time, but never encountered it for sale anywhere on this side of the Atlantic. The Dungeons & Dragons Master Rules receive a (in my opinion) very charitable 8 out of 10, while Unearthed Arcana is given a serious drubbing (4 out of 10). The reviewer, Paul Cockburn, has many reasonable criticisms of the book, a great many of which I share. His biggest complaint seems to be that UA "is about as important to running a good game as Official character sheets or figures." I find it hard to disagree.

"2020 Vision" is a new column "covering fantasy and science-fiction movies" by Colin Greenland. The inaugural column focuses on two movies, Back to the Future, which Greenland enjoyed, and The Goonies, which he most certainly did not. He also reviews The Bride, "a hokey new variation on The Bride of Frankenstein," about which his opinion is more mixed. Dave Langford's "Critical Mass," meanwhile, does what he usually does: looks down his nose at various books, only a couple of which I've ever heard of, let alone read. It's a shame really, because it's clear that Langford is quite a talented writer in his own right, but most of his columns simply leave me flat. Some of that, no doubt, is the alienating effect of time. He is, after all, writing about the literary ephemera of three or more decades ago; it would be a miracle if it were still of vital interest to me today.

"Power & Politics" is an interview with Derek Carver, in which he talks about his boardgame, Warrior Knights. From the interview, it would seem the game is in the same general ballpark as Kingmaker in terms of overall focus and complexity, though it's set in a fictitious medieval European country rather than a real one. The game was (of course) published by Games Workshop, hence the two pages devoted to what is essentially an advertisement for it.

I usually don't comment on the letters page of most issues of White Dwarf, because they're rarely of lasting import. This issue is a little different in that it's been expanded to two pages (from the usual one) and it's given over to lots of arguments back and forth about the merits of previous articles, not to mention letters attacking and defending said articles. This time, much ink is spilled with regards to Marcus L. Rowland's review of Twilight: 2000 from issue #68. Rowland, you may recall, intensely disliked the game and what he saw as its inherent immorality, calling it "fairly loathsome." Judging by the letters in this issue, not everyone shared Rowland's assessment and felt the need to say so. Of course, others very much agreed with him. Reading the letters for and against, it's a reminder that the past really is a foreign country.

Simon Burley's "The American Dream" is a lengthy scenario for Golden Heroes that focuses on a former American superheroine who has gone rogue in order to take down corruption within the secret government organization that trained her. It's delightfully overwrought and cynical and very much in keeping with the general spirit of the late 1980s. "3-D Space" by Bob McWilliams takes another stab at a classic Traveller "problem," namely, the game's star maps are two-dimensional. As he so often does, McWilliams makes a challenging topic easy to understand. In this case, though, I remain unconvinced that much is gained by adopting a more "realistic" style of stellar mapping.

"Star Spray" by Graham Staplehurst is an adventure set in J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth, written for use with both AD&D and Middle-earth Role Playing. The adventure takes place in southern Gondor and concerns the fate of Maglor, the second son of Feänor, who disappeared during the First Age. It's clear that Staplehurst knows his Tolkien and "Star Spray" makes good use of that knowledge to present a situation that's more than just a dungeon delve in Middle-earth. Good stuff!

"First This, Then That" by Oliver Johnson is a fairly forgettable bit of advice on adjudicating the rules of RuneQuest. I'm sure the article seemed very relevant at the time, but, in retrospect, it's hard to muster much interest in it – the fate of a lot of gaming material, alas. "Cults of the Dark Gods 2" by A.J. Bradbury looks at the Bavarian Illuminati from the perspective of Call of Cthulhu. "A New Approach to Magic Weapons" by Michael Williamson is an interesting, if frustratingly sketchy, plea to give magic weapons in AD&D more "oomph" by rooting them in a setting's history. I'm very sympathetic to this approach, since I think there should be no "generic" magic weapons in any campaign, but, unfortunately, Williamson provides only the barest hint of a way to implement this mechanically. That's a shame, because I very much think he's on to something.

"Jungle Jumble" gives us four new jungle-themed monsters for use with AD&D, including vampire bats and army wasps. Joe Dever's "Dioramas" is the second part of his look at this intriguing topic, focusing this time on "scenic effects," like sand, snow, water, and foliage. I continue to find this column enjoyable, despite my own lack of experience with miniatures painting. The issue also includes new episodes of its long-running comics, "Thrud the Barbarian," "Gobbledigook," and "The Travellers," all of which are diverting, if not always memorably so.

The transformation of White Dwarf into a full-on Games Workshop house organ continues apace. While there are still quite a few articles devoted to non-GW games and topics, more and more space is devoted to GW's own publications. While probably a good business decision – Games Workshop still exists today and most of its contemporary competitors do not – it does lessen the magazine's appeal in my eyes. I'm going to keep soldiering on with this series for the foreseeable future. How long I'll be able to do so is another question ...

May 1, 2023

Starship Pilots of Charted Space, Unite!

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers